Abstract

Background

Itch is a well-established symptom in cutaneous disease. However, little is known about the burden of itch outside the dermatology setting.

Purpose

To determine the prevalence and impact of itch on quality of life (QOL) in the general internal medicine setting.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study of 2076 adults from an outpatient general internal medicine clinic, using an audio computer-assisted self-administered interview. A history of itch (acute or chronic) and other physical symptoms in the past week, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) 10-item Global Health Questionnaire scores, and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 scores were assessed.

Results

The prevalence of itch was 39.9 % and increased with age from 33.1 % at age 19–39 years to 45.9 % at age ≥80 years. In multivariable models controlled for socio-demographics, even feeling “a little” or “some” distress from itch was significantly associated with lower PROMIS global physical and mental health T-scores and estimated health utility scores (P ≤ 0.01). Further, feeling “quite a lot” of distress or “very much” distress from itch was associated with higher adjusted odds ratios for depressed mood (4.91 [95 % confidence interval (CI) 3.36–7.18]) and anhedonia (4.46 [95 % CI 3.07–6.47]). The patient burden of itch was similar to those of pain, constipation, sexual dysfunction, cough, and weight loss.

Conclusions

Itch occurs commonly in the primary care setting and is associated with poor QOL. Physicians should inquire about itch and its associations during review of systems. Future studies are needed to distinguish between the effects of acute and chronic itch.

1 Introduction

Itch is a common symptom encountered in the dermatology setting. Itch occurring in dermatologic disease has been associated with sleep disturbances [1], psychological and behavioral disorders [2], fractures and other injuries [2, 3], and impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [1].

However, little is known about the epidemiology and burden of itch outside the dermatologic setting. Previous studies have assessed the characteristics of pruritus in geriatric populations [4] and in specific diseases, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis and renal failure [5, 6]. Yet, no studies have examined rates of itch in the general internal medicine setting. It is important to understand the global burden of itch in order to assess the unmet needs for the assessment and treatment of itch. Further, most previous studies have assessed the prevalence of itch and occasionally related symptoms, but no studies have compared the prevalence and burden of itch with those of other symptoms, which is necessary in order to understand the burden of itch, identify unmet needs, and prioritize clinical resources. We hypothesized that itch is associated with worse HRQOL impairment than many other common symptoms. The present study examined the prevalence of itch and HRQOL impairment from itch, and compared them with other common symptoms in adults seen in an internal medicine setting.

2 Methods

2.1 Participant Recruitment

Adult patients (aged >18 years) were recruited from the general internal medicine clinic of the Cook County Health and Hospitals System (CCHHS) in Chicago, IL, USA, as previously described [7]. Subjects were invited to participate between April 8, 2011 and July 27, 2012. This study was approved by the CCHHS institutional review board (protocol #14-096).

Surveys were completed in English or Spanish, using audio computer-assisted self-administered interviews (ACASIs) on a computer kiosk with a touch screen and headphones in the clinic waiting area. Survey items were presented simultaneously by visual display on the monitor and audio files reading each question and response. The surveys were administered in either English or Spanish as per each patient’s preference. Several practice questions were used to establish comfortability and proficiency with the software. The software was developed using the C# language on the .NET framework. ACASI responses were stored in an SQL server clinical data warehouse (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA, USA) maintained by the local institution’s Department of Medicine. All patient encounters were included in the study, and patients with dermatoses were not excluded.

2.2 Data Collection

HRQOL was assessed using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Questionnaire, which includes 10 items related to overall health, quality of life (QOL), physical and mental health, satisfaction with the ability to carry out social activities and relationships, ability to carry out everyday physical activities, being bothered by emotional problems, fatigue, and pain. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ2) was used to assess feeling “down, depressed, or hopeless” and “little interest or pleasure in doing things.” Patients were asked about the occurrence of, and distress from, 17 physical symptoms: lack of energy, pain, drowsiness, dizziness, vomiting, shortness of breath, nausea, dry mouth, lack of appetite, bloating, change of taste, itch, sexual dysfunction, diarrhea, constipation, cough, and weight loss. The symptom response scales were 0: absent; 1: present, “a little” distress; 2: present, “some” distress; 3: present, “quite a lot” of distress; and 4: present, “very much” distress.

2.3 Data Analysis

All data processing and statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4. Complete data analysis was performed for all variables, i.e., subjects with missing data were excluded. There were no significant differences in any socio-demographic characteristics between missing and non-missing values.

The PROMIS global physical and mental health T-scores were calculated using the recommended scoring method, which calibrated each score to a US national mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 [8]. The health utility (preference) score was calculated using a published algorithm that maps the PROMIS global health score to the EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D) score [9]. Means ± SDs are presented. T tests and analysis of variance were used to determine associations between PROMIS scores and age, gender, race/ethnicity, and language of interview. The prevalence and 95 % confidence interval (CI) of each symptom was determined overall and stratified by age. The means of the aforementioned scores were determined in patients who reported “quite a lot” or “very much” for each of the 17 symptoms, and were ranked in ascending order. Associations between itch (a categorical independent variable) and the individual PROMIS global health item responses (dependent variables) were tested using ordinal logistic regression. Associations of PROMIS global health total raw scores, physical and mental health T-scores, and estimated EQ-5D utility scores (dependent variables) with itch (a categorical independent variable) were tested using linear regression. The multivariable regression models included age, gender, race/ethnicity, and language of interview. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and adjusted beta-coefficients, with 95 % CIs, were estimated.

A two-sided P value <0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance for all estimates. However, the multiple dependent tests performed in this study (k = 32) increased the risk of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis. Therefore, P values near 0.05 should be interpreted with caution.

3 Results

3.1 Study Characteristics

An invitation to complete surveys was conveyed 2848 times. Patients agreed to sit in front of the kiosk 2561 times (90 %), on which 2076 unique patients provided some data through the kiosk. Overall, 58.5 % of patients were female, 54.8 % and 23.8 % were Black and Hispanic, respectively, and 19.9 % participated using Spanish as the language of interview (see Supplemental Table 1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). PROMIS physical health T-scores were higher at younger ages and in females. In contrast, PROMIS total raw scores and mental health T-scores were not associated with these socio-demographic variables.

3.2 Prevalence of Itch

Overall, 97.5 % of patients reported at least one symptom in the past week. More than 4 in 5 patients reported having lack of energy or pain. At least 1 in 4 patients reported having ≥1 of 14 other symptoms (see Table 1). Itch occurred in 39.9 % (37.7–42.0 %) of patients overall and was more common than lack of appetite, nausea, sexual dysfunction, weight loss, change of taste, and diarrhea and vomiting. The prevalence of itch increased with age from 33.1 % (25.4–40.8 %) at age 19–39 years to 45.9 % (35.3–56.5 %) at age ≥80 years (see Table 1). Itch was more commonly reported in men (43.7 % [40.2–47.1 %]) than in women (37.2 % [34.3–40.0 %]; P = 0.004). There were no significant differences in the prevalence of itch between different racial/ethnic groups (P = 0.92) or in the survey language (P = 0.57).

Table 1.

Prevalence of symptoms overall and stratified by age

| Rank | Symptom | Frequency [n] | Missing subjects [n] | Prevalence [% (95 % CI)] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Overall, n = 2076 | Age | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 19–39 years, n = 149 | 40–59 years, n = 963 | 60–79 years, n = 866 | 80–99 years, n = 98 | |||||

| 1 | Lack of energy | 1680 | 124 | 86.1 (84.5–87.6) | 75.7 (68.8–82.6) | 86.4 (84.1–88.6) | 87.4 (85.1–89.7) | 88.5 (81.8–95.2) |

| 2 | Pain | 1587 | 158 | 82.7 (81.0–84.4) | 72.4 (65.1–79.7) | 85.3 (83.0–87.7) | 81.6 (78.9–84.3) | 82.9 (74.8–91.1) |

| 3 | Drowsiness | 1240 | 138 | 64.0 (61.8–66.1) | 65.8 (58.0–73.5) | 66.1 (63.1–69.2) | 60.7 (57.3–64.1) | 68.7 (58.7–78.7) |

| 4 | Cough | 1175 | 111 | 59.8 (57.6–62.0) | 46.9 (38.9–55.0) | 59.5 (56.4–62.7) | 61.3 (58.0–64.7) | 70.7 (60.9–80.6) |

| 5 | Dry mouth | 1147 | 137 | 59.2 (57.0–61.3) | 47.3 (39.2–55.4) | 61.0 (57.9–64.2) | 58.7 (55.2–62.1) | 63.9 (53.5–74.2) |

| 6 | Shortness of breath | 941 | 128 | 48.3 (46.1–50.5) | 39.7 (31.8–47.7) | 51.4 (48.2–54.6) | 47.2 (43.8–50.7) | 39.3 (28.8–49.7) |

| 7 | Bloating | 928 | 142 | 48.0 (45.8–50.2) | 44.8 (36.7–52.9) | 52.6 (49.4–55.9) | 43.6 (40.1–47.0) | 44.4 (34.2–54.7) |

| 8 | Dizziness | 819 | 134 | 42.2 (40.0–44.4) | 41.8 (33.8–49.8) | 45.8 (42.6–49.0) | 37.8 (34.4–41.2) | 44.2 (33.7–54.7) |

| 9 | Constipation | 813 | 140 | 42.0 (39.8–44.2) | 27.9 (20.6–35.1) | 41.5 (38.3–44.7) | 43.7 (40.2–47.2) | 55.8 (45.3–66.3) |

| 10 | Itch | 771 | 142 | 39.9 (37.7–42.0) | 33.1 (25.4–40.8) | 40.8 (37.6–44.0) | 39.4 (35.9–42.8) | 45.9 (35.3–56.5) |

| 11 | Lack of appetite | 670 | 128 | 34.4 (32.3–36.5) | 34.0 (26.3–41.7) | 36.8 (33.6–39.9) | 31.2 (28.0–34.4) | 39.5 (29.2–49.9) |

| 12 | Nausea | 665 | 131 | 34.2 (32.1–36.3) | 35.2 (27.4–43.0) | 37.7 (34.6–40.9) | 31.0 (27.8–34.2) | 24.1 (15.1–33.1) |

| 13 | Sexual dysfunction | 627 | 207 | 33.5 (31.4–35.7) | 34.9 (27.2–42.7) | 40.7 (37.5–44.0) | 26.8 (23.6–30.0) | 15.3 (7.6–23.0) |

| 14 | Weight loss | 529 | 142 | 27.4 (25.4–29.3) | 29.1 (21.7–36.4) | 27.7 (24.7–30.6) | 25.2 (22.2–28.2) | 42.0 (31.2–52.7) |

| 15 | Change of taste | 517 | 130 | 26.6 (24.6–28.5) | 24.0 (17.0–30.9) | 27.1 (24.3–30.0) | 25.2 (22.1–28.2) | 37.5 (27.4–47.6) |

| 16 | Diarrhea | 479 | 125 | 24.6 (22.6–26.5) | 27.8 (20.5–35.1) | 27.9 (25.0–30.8) | 21.0 (18.1–23.8) | 15.7 (7.8–23.5) |

| 17 | Vomiting | 182 | 122 | 9.3 (8.0–10.6) | 11.0 (5.9–16.0) | 11.3 (9.2–13.3) | 6.8 (5.1–8.6) | 8.5 (2.5–14.6) |

CI confidence interval

3.3 Association between Itch and HRQOL

In multivariable models controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and language of interview, feeling a little distress or some distress from itch, and even more so quite a lot of distress or very much distress from itch, was significantly associated with each item of PROMIS global health, including poorer overall health, QOL, physical health, mental health, satisfaction with social activities and relationships, ability to carry out everyday physical activities and usual social activities and roles, more severe fatigue, and being bothered by emotional problems (ordinal logistic regression; P ≤ 0.01 for all) (see Table 2). The frequencies of missing values are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ordinal logistic regression models of quality of life in patients with distress from itcha

| Distress from itch | Frequency [%]b | OR (95 % CI) | P value | aOR (95 % CI) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall health | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | Excellent | ||||

| No itch | 110 (9.9) | 409 (36.9) | 426 (38.4) | 134 (12.1) | 31 (2.8) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 70 (12.2) | 243 (42.5) | 206 (36.0) | 42 (7.3) | 11 (1.9) | 1.40 (1.17–1.69) | 0.0004 | 1.40 (1.15–1.69) | 0.0006 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 49 (30.8) | 74 (46.5) | 31 (19.5) | 5 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4.12 (3.00–5.65) | <0.0001 | 4.26 (3.08–5.90) | < 0.0001 |

| Quality of life | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | Excellent | ||||

| No itch | 55 (5.0) | 336 (30.3) | 471 (42.5) | 178 (16.1) | 69 (6.2) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 37 (6.5) | 207 (36.6) | 238 (42.1) | 68 (12.0) | 16 (2.8) | 1.46 (1.21–1.77) | <0.0001 | 1.40 (1.16–1.70) | 0.0006 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 24 (15.2) | 64 (40.5) | 54 (34.2) | 11 (7.0) | 5 (3.2) | 2.57 (1.88–3.51) | <0.0001 | 2.51 (1.82–3.46) | < 0.0001 |

| Physical health | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | Excellent | ||||

| No itch | 117 (10.6) | 428 (38.7) | 431 (38.9) | 103 (9.3) | 28 (2.5) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 74 (12.9) | 265 (46.3) | 191 (33.3) | 37 (6.5) | 6 (1.1) | 1.46 (1.21–1.76) | <0.0001 | 1.44 (1.19–1.75) | 0.0002 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 43 (28.1) | 65 (42.5) | 39 (25.5) | 5 (3.3) | 1 (0.7) | 2.92 (2.12–4.02) | <0.0001 | 3.00 (2.16–4.16) | < 0.0001 |

| Mental health | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | Excellent | ||||

| No itch | 44 (4.0) | 203 (18.4) | 395 (35.7) | 278 (25.1) | 186 (16.8) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 42 (7.3) | 138 (23.9) | 211 (36.5) | 123 (21.3) | 64 (11.1) | 1.56 (1.30–1.87) | <0.0001 | 1.49 (1.24–1.80) | < 0.0001 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 21 (13.6) | 52 (33.6) | 44 (28.4) | 25 (16.1) | 13 (8.4) | 2.81 (2.07–3.82) | <0.0001 | 3.00 (2.19–4.12) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfaction with social activities and relationships | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | Excellent | ||||

| No itch | 53 (4.8) | 203 (18.4) | 409 (37.1) | 285 (25.8) | 154 (14.0) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 51 (8.9) | 129 (22.6) | 249 (43.5) | 108 (18.9) | 35 (6.1) | 1.79 (1.49–2.15) | <0.0001 | 1.73 (1.43–2.09) | < 0.0001 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 31 (19.8) | 49 (31.2) | 48 (30.6) | 19 (12.1) | 10 (6.4) | 3.60 (2.65–4.90) | <0.0001 | 3.52 (2.57–4.83) | < 0.0001 |

| Extent able to carry out everyday physical activities | Not at all | A little | Moderately | Mostly | Completely | ||||

| No itch | 27 (2.4) | 273 (24.4) | 355 (31.8) | 179 (16.0) | 284 (25.4) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 15 (2.6) | 147 (25.6) | 217 (37.8) | 107 (18.6) | 88 (15.3) | 1.31 (1.09–1.57) | 0.004 | 1.27 (1.05–1.52) | 0.01 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 14 (9.2) | 56 (36.6) | 50 (32.7) | 17 (11.1) | 16 (10.5) | 2.64 (1.94–3.61) | <0.0001 | 2.69 (1.95–2.00) | < 0.0001 |

| Fatigue | Very severe | Severe | Moderate | Mild | None | ||||

| No itch | 25 (2.3) | 106 (9.6) | 458 (41.4) | 359 (32.4) | 159 (14.4) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 16 (2.8) | 76 (13.3) | 267 (46.7) | 173 (30.2) | 40 (7.0) | 1.53 (1.27–1.84) | <0.0001 | 1.49 (1.23–1.81) | < 0.0001 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 19 (12.2) | 42 (26.9) | 57 (36.5) | 33 (21.2) | 5 (3.2) | 4.07 (2.97–5.59) | <0.0001 | 4.43 (3.20–6.13) | < 0.0001 |

| How often bothered by emotional problems | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | ||||

| No itch | 41 (3.7) | 130 (11.8) | 426 (38.8) | 262 (23.8) | 240 (21.8) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 35 (6.1) | 87 (15.3) | 281 (49.3) | 109 (19.1) | 58 (10.2) | 1.86 (1.55–2.25) | <0.0001 | 1.93 (1.59–2.34) | < 0.0001 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 22 (14.3) | 42 (27.3) | 56 (36.4) | 24 (15.6) | 10 (6.5) | 3.80 (2.78–5.21) | <0.0001 | 4.10 (2.97–5.66) | < 0.0001 |

| Carrying out usual social activities and roles | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | Excellent | ||||

| No itch | 55 (4.9) | 255 (22.8) | 397 (35.5) | 262 (23.4) | 149 (13.3) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 42 (7.2) | 163 (27.9) | 243 (41.6) | 103 (17.6) | 33 (5.7) | 1.66 (1.39–2.00) | <0.0001 | 1.61 (1.33–1.94) | < 0.0001 |

| Distress from itch | Frequency [%]b | OR (95 % CI) | P value | aOR (95 % CI) | P value | ||||

| Quite a lot/very much | 20 (12.6) | 64 (40.3) | 55 (34.6) | 11 (6.9) | 9 (5.7) | 3.19 (2.35–4.34) | <0.0001 | 3.24 (2.37–4.44) | < 0.0001 |

aOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio

Ordinal logistic regression models were constructed with different impairments of quality of life modeled as the dependent variables (see Sect. 2) and distress from itch as the ordinal predictor. The models met proportional odds assumptions (score test, P > 0.05). ORs and 95 % CIs were estimated. Multivariable models were constructed, which included gender (male/female); age (continuous); race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and other); and language of the interview (English/Spanish) as covariates. aORs and 95 % CIs were estimated

Missing data were encountered in 0 subjects (0.0 %) for age, gender, language, and date of interview; 85 subjects (5.4 %) for race/ethnicity; 40 subjects (2.6 %) for overall health rating; 115 subjects (5.5 %) for quality-of-life rating; 129 subjects (6.2 %) for physical health rating; 122 subjects (5.9 %) for mental health rating; 124 subjects (6.0 %) for satisfaction with social activities and relationships; 120 subjects (5.8 %) for extent able to carry out everyday physical activities; 132 subjects (6.4 %) for fatigue; 144 subjects (6.9 %) for how often bothered by emotional problems; 104 subjects (5.0 %) for carrying out usual social activities and roles; and 142 subjects (6.8 %) for itch in the past week

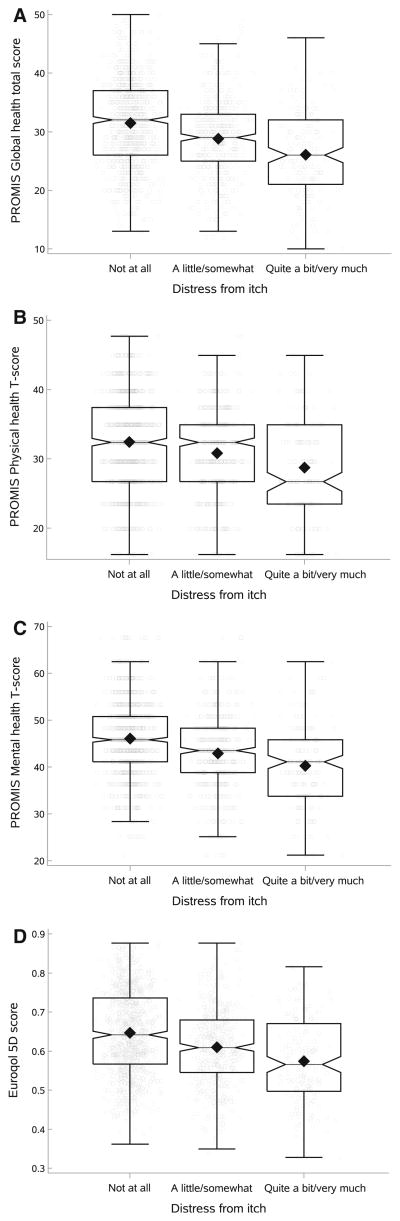

Patients feeling a little distress or some distress from itch, and even more so quite a lot of distress or very much distress from itch, had significantly lower PROMIS total raw scores (linear regression; adjusted beta values [95 % CIs] for a little/some: −2.46 [−3.29 to −1.62], quite a lot/very much: −6.66 [−8.04 to −5.28]), physical health T-scores (a little/some: −1.61 [−2.34 to −0.89], quite a lot/very much: −4.95 [−6.15 to −3.75]), and mental health T-scores (a little/some: −3.14 [−4.06 to −2.22], quite a lot/very much: −6.73 [−8.25 to −5.21]); and estimated EQ-5D utility scores (a little/some: −0.04 [−0.05 to −0.02], quite a lot/very much: −0.09 [−0.11 to −0.07]) (P <0.0001 for all; see Fig. 1). There were no significant interactions of itch with age, gender, race/ethnicity, or language of interview as predictors of any of the aforementioned outcomes (P > 0.08 for all).

Fig. 1.

Associations between distress from itch and poorer quality of life. Responses for itch were divided into no itch, “a little” distress or “some” distress from itch, and “quite a lot” of distress or “very much” distress from itch. Box-and-whisker plots and overlaid jitter plots of a Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) total raw scores, b PROMIS physical health T-scores, c PROMIS mental health T-scores, and d EuroQol 5D total scores are presented for each level of itch. P <0.0001 for all comparisons between no itch and a little distress or some distress, between no itch and quite a lot of distress or very much distress, and between a little distress or some distress and quite a lot of distress or very much distress

3.4 Association Between Itch, Depressed Mood, and Anhedonia

In multivariable models controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and language of interview, even feeling a little distress or some distress from itch was significantly associated with higher odds of either depressed mood or anhedonia (see Table 3). However, patients feeling quite a lot of distress or very much distress from itch had even higher odds than those who felt only a little distress or some distress (P < 0.0001 for all).

Table 3.

Ordinal logistic regression models of depressed mood and anhedonia in the past 2 weeks in patients with distress from itcha

| Distress from itch | Frequency [%]b | OR (95 % CI) | P value | aOR (95 % CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood | Not at all/several days | More than half the days/nearly every day | ||||

| No itch | 949 (87.1) | 141 (12.9) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 462 (79.8) | 117 (20.2) | 1.70 (1.30–2.23) | < 0.0001 | 1.68 (1.28–2.22) | < 0.0001 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 89 (58.6) | 63 (41.5) | 4.76 (3.30–6.88) | < 0.0001 | 4.91 (3.36–7.18) | < 0.0001 |

| Anhedonia | Not at all/several days | More than half the days/nearly every day | ||||

| No itch | 907 (84.5) | 166 (15.5) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 423 (75.1) | 140 (24.9) | 1.81 (1.40–2.33) | < 0.0001 | 1.77 (1.37–2.30) | < 0.0001 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 82 (54.7) | 68 (45.3) | 4.53 (3.16–6.50) | < 0.0001 | 4.46 (3.07–6.47) | < 0.0001 |

| Any depressed mood and anhedonia | Either | Both | ||||

| No itch | 267 (46.1) | 312 (53.9) | 1.00 [reference] | – | 1.00 [reference] | – |

| A little/some | 155 (39.0) | 242 (61.0) | 1.34 (1.03–1.73) | 0.03 | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) | 0.08 |

| Quite a lot/very much | 30 (23.8) | 96 (76.2) | 2.74 (1.76–4.26) | < 0.0001 | 2.81 (1.78–4.41) | < 0.0001 |

aOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio

Ordinal logistic regression models were constructed with depressed mood and anhedonia as the dependent variables (from the Patient Health Questionnaire-2) and distress from itch as the ordinal predictor. The models did not meet proportional odds assumptions (score test, P < 0.001 for both). Therefore, depressed mood and anhedonia were dichotomized into (1) not at all or several days in the past 2 weeks; or (2) more than half the days or nearly every day in the past 2 weeks. In addition, models were constructed with both depressed mood and anhedonia versus either symptom as the dependent variable. ORs and 95 % CIs were estimated. Multivariable models were constructed, which included gender (male/female); age (continuous); race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and other); and language of the interview (English/Spanish) as covariates. aORs and 95 % CIs were estimated

Missing data were encountered in 0 subjects (0.0 %) for age, gender, language, and date of interview; 85 subjects (5.4 %) for race/ethnicity; 12 subjects (0.6 %) for depressed mood or anhedonia; and 142 subjects (6.8 %) for itch in the past week

3.5 Comparison of Effects of Itch and Other Symptoms on HRQOL

All 17 symptoms were associated with impaired HRQOL; that is, patients who reported “quite a lot” of distress or “very much” distress from each symptom had lower PROMIS total raw scores, physical and mental health T-scores, and EQ-5D scores (analysis of variance; P <0.0001 for all). The mean PROMIS and EQ-5D scores, ±SDs, are presented in Table 4. PROMIS total scores were lower in patients (ranked #12) who reported “quite a lot” of distress from itch or “very much” distress from itch than in those who similarly reported distress from pain, constipation, sexual dysfunction, cough, and weight loss. Similar results were found for EQ-5D scores. In particular, itch was associated with a relatively larger impact on mental health (ranked #13) than on physical health (ranked #15) in comparison with other symptoms (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Impact of distress from symptoms on health-related quality of life

| Symptom causing quite a lot of distress/very much distress | PROMIS total raw score | PROMIS physical health T-score | PROMIS mental health T-score | EuroQol 5D score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean ± SD | Rank | Mean ± SD | Rank | Mean ± SD | Rank | Mean ± SD | Rank | |

| Vomiting | 21.37 ± 7.06 | 1 | 30.58 ± 7.41 | 1 | 35.21 ± 9.37 | 1 | 0.50 ± 0.10 | 1 |

| Dizziness | 22.97 ± 6.58 | 2 | 33.02 ± 7.16 | 3 | 37.13 ± 9.06 | 2 | 0.52 ± 0.52 | 2 |

| Nausea | 23.07 ± 6.59 | 3 | 32.70 ± 6.92 | 2 | 37.27 ± 8.79 | 3 | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 3 |

| Drowsiness | 23.55 ± 6.57 | 4 | 33.58 ± 6.81 | 6 | 37.79 ± 8.75 | 5 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 7 |

| Shortness of breath | 23.55 ± 6.05 | 5 | 33.40 ± 6.20 | 4 | 38.62 ± 8.32 | 9 | 0.53 ± 0.08 | 4 |

| Lack of appetite | 23.68 ± 6.81 | 6 | 33.96 ± 7.24 | 9 | 37.93 ± 9.10 | 6 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 8 |

| Change of taste | 23.79 ± 6.94 | 7 | 33.75 ± 8.12 | 7 | 38.05 ± 8.97 | 7 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 5 |

| Lack of energy | 23.87 ± 6.09 | 8 | 33.56 ± 6.23 | 5 | 38.66 ± 8.31 | 10 | 0.54 ± 0.09 | 6 |

| Diarrhea | 24.48 ± 7.02 | 9 | 34.73 ± 7.26 | 12 | 37.78 ± 9.15 | 4 | 0.55 ± 0.11 | 12 |

| Bloating | 24.50 ± 6.32 | 10 | 34.30 ± 7.22 | 11 | 38.57 ± 8.08 | 8 | 0.55 ± 0.10 | 11 |

| Dry mouth | 24.61 ± 6.27 | 11 | 34.29 ± 6.64 | 10 | 38.88 ± 8.06 | 11 | 0.55 ± 0.09 | 10 |

| Itch | 24.91 ± 6.62 | 12 | 35.16 ± 7.44 | 15 | 39.51 ± 8.70 | 13 | 0.56 ± 0.10 | 13 |

| Pain | 24.97 ± 6.20 | 13 | 33.86 ± 5.82 | 8 | 40.50 ± 8.68 | 16 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | 9 |

| Constipation | 25.05 ± 6.28 | 14 | 35.05 ± 6.84 | 14 | 39.36 ± 7.98 | 12 | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 15 |

| Sexual dysfunction | 25.11 ± 7.25 | 15 | 35.03 ± 7.72 | 13 | 39.68 ± 8.81 | 14 | 0.56 ± 0.10 | 14 |

| Cough | 25.86 ± 6.49 | 16 | 35.89 ± 7.46 | 16 | 40.19 ± 8.50 | 15 | 0.57 ± 0.10 | 16 |

| Weight loss | 27.97 ± 6.02 | 17 | 37.66 ± 7.02 | 17 | 42.40 ± 7.78 | 17 | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 17 |

PROMIS Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, SD standard deviation

4 Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed data from 2076 adults from an inner-city internal medicine clinic and found that almost 40 % of patients experienced itch in the previous week that caused some level of distress. While data were available for multiple other symptoms, we particularly focused on itch because it has been largely neglected and no studies have examined how itch compares with other symptoms. Itch was reported more frequently than lack of appetite, weight loss, change of taste, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and sexual dysfunction. Itch was associated with impairment of all aspects of HRQOL that were assessed, especially mental health, as well as higher odds of depressed mood and anhedonia. Patients with chronic itch are known to have higher rates of depression [10]. In addition, depression may also worsen itch, and patients with chronic itch often experience improvement of their itch with the use of antidepressant medications and other psychological interventions. Thus, the relationship between itch and impaired HRQOL may be bidirectional, where itch decreases HRQOL and decreased HRQOL from other etiologies prompts more itch. Finally, the present study found that itch was associated with overall HRQOL impairment similar to that associated with pain and more severe than that associated with constipation, sexual dysfunction, cough, or weight loss. Together, the results suggest the presence of a considerable patient burden and mental health distress secondary to itch in adults in an urban primary care setting.

The results underscore the importance of including itch in a review of systems. The symptoms of pain, constipation, etc., are routinely assessed by clinicians. Yet, itch is rarely assessed, despite being associated with as much or more HRQOL impairment. Surveillance for itch may help with early detection of underlying medical conditions, e.g., liver or renal disease. The considerable burden of itch and other symptoms on HRQOL suggests that a comprehensive review of systems may yield previously unrecognized ways to improve patients’ HRQOL. Currently, there are no medications approved by the US Food and Drug Association for the treatment of itch. The high prevalence and patient burden of itch demonstrated in this study highlight a large practice gap and beg for future research into medical and psychological treatment approaches for itch.

The present study demonstrates that itch is both common and distressing to a large subset of adults in an urban primary care setting. Few studies have previously assessed the burden of itch in primary care. Analysis of data from the 1999–2009 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that itch was a symptom reported at approximately 1 % of all out-patient visits [11]. Similarly, analysis of data from the 1998–2003 Australian Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) program found that itch was a reason for the encounter in 0.6 % of encounters [12]. However, these studies reported rates of clinical encounters primarily focused on itch, did not engage patients directly, and were not able to assess how many patients actually itched. The high rates of itch symptoms and low rates of encounters for itch suggest that itch may not be adequately addressed in the clinical setting. This may be because clinicians do not routinely ask about itch and/or patients do not voluntarily mention their concerns about itch. A previous questionnaire-based study of 492 Dutch adults from general practice with commonly encountered skin diseases in the preceding 12 months found that 53.5 % reported itch in the past 4 weeks [13]. However, that study focused on patients with dermatologic diseases and did not assess the prevalence of itch across all patients in general practice. Further, the questionnaires were not sent at the time of the physician encounter and may not have accurately reflected the prevalence of itch in practice. A recent study of 302 Hispanic geriatric patients residing in nursing homes or attending a geriatric outpatient clinic found a 25 % prevalence of chronic itch [4]. In contrast, we found a 39.9 % prevalence of itch causing some distress in the past week, overall. However, the prevalence of itch increased with age, with almost half of patients aged ≥80 years reporting itch. This is likely related to the higher rates of senile pruritus in the elderly population, as well as underlying medical conditions that are associated with itch, e.g., diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Nevertheless, the results suggest that itch may be even more common than previously recognized, especially in the elderly population. Though we were not able to assess whether the itch was an acute or chronic itch per se, it may be that any itch, perhaps even a short-term itch, is sufficiently distressing for patients to result in impaired QOL.

This study had several strengths, including a large sample size, high response rates, and use of validated QOL and symptom instruments. The questionnaires were administered at the time of clinic visits, rather than via mail-based or internet-based surveys. Thus, the results are likely more reflective of the symptoms actually encountered in general practice. The study assessed 17 physical symptoms, including itch, which uniquely allowed for comparison of QOL impairment in patients with itch verses other symptoms. However, the study had some weaknesses as well. First, the patient population was from an inner-city population and predominantly racial and ethnic minorities with relatively low baseline HRQOL, which raises questions about generalizability to the entire US population. Second, the study assessed symptoms and HRQOL at a single time point. However, itch often has a waxing and waning course that may not be captured in a cross-sectional study. Third, we did not assess whether the itch was an acute or chronic itch. Finally, we did not assess the etiologies of itch. Future studies are underway to determine the longitudinal course and comorbidities of itch.

5 Conclusions

The present study aimed to determine the prevalence and impact of itch on QOL. We found that itch is a common symptom reported by patients in general internal medicine. Further, itch was associated with significant HRQOL impairment, depressed mood, and anhedonia. Itch warrants greater attention in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Little is known about the epidemiology and burden of itch occurring in the primary care setting.

The present study found that itch was very common in the internal medicine setting and was associated with poor quality of life and depressive symptoms. The patient burden of itch was similar to those of pain and many other commonly encountered symptoms.

Itch should be routinely assessed in review of systems in the primary care setting.

Acknowledgments

Funding This publication was made possible with support from the Dermatology Foundation and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Grant Numbers K12HS023011 and R24 HS19481-01 to support technology implementation.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest Jonathan Silverberg, David Cella, William Trick, and Keiki Hinami have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval/informed consent This study was approved by the CCHHS institutional review board (protocol #14-096). All participants provided written informed consent for study participation.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0215-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Author contributions Study concept and design: Keiki Hinami, William Trick, and Jonathan Silverberg. Acquisition of data: Keiki Hinami, William Trick, and Jonathan Silverberg. Analysis and interpretation of data: Jonathan Silverberg, Keiki Hinami, and David Cella. Drafting of the manuscript: Jonathan Silverberg, David Cella, and Keiki Hinami. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Jonathan Silverberg, David Cella, William Trick, and Keiki Hinami. Statistical analysis: Jonathan Silverberg. Obtaining funding: Jonathan Silverberg, William Trick, and David Cella.

References

- 1.Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, Fishbein AB, Zee PC. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(1):56–66. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg N, Silverberg JI. Association between childhood allergic disease, psychological comorbidity, and injury requiring medical attention. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(6):525–32. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg N, Silverberg JI. Association between eczema and increased fracture and bone or joint injury in adults: a US population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(1):33–41. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valdes-Rodriguez R, Mollanazar NK, Gonzalez-Muro J, Nattkemper L, Torres-Alvarez B, Lopez-Esqueda FJ, et al. Itch prevalence and characteristics in a Hispanic geriatric population: a comprehensive study using a standardized itch questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(4):417–21. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotthardt DN, Rupp C, Bruhin M, Schellberg D, Weiss KH, Stefan R, et al. Pruritus is associated with severely impaired quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26(12):1374–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Susel J, Batycka-Baran A, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Uraemic pruritus markedly affects the quality of life and depressive symptoms in haemodialysis patients with end-stage renal disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(3):276–81. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinami K, Smith J, Deamant CD, Kee R, Garcia D, Trick WE. Health perceptions and symptom burden in primary care: measuring health using audio computer-assisted self-interviews. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1575–83. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0884-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873–80. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revicki DA, Kawata AK, Harnam N, Chen WH, Hays RD, Cella D. Predicting EuroQol (EQ-5D) scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items and domain item banks in a United States sample. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(6):783–91. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9489-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schut C, Mollanazar NK, Kupfer J, Gieler U, Yosipovitch G. Psychological interventions in the treatment of chronic itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(2):157–61. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shive M, Linos E, Berger T, Wehner M, Chren MM. Itch as a patient-reported symptom in ambulatory care visits in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(4):550–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britt H, Pan Y, Miller GC, Valenti L, Charles J, Knox S, et al. Presentations of ‘itch’ in Australian general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33(7):488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhoeven EW, Kraaimaat FW, van de Kerkhof PC, van Weel C, Duller P, van der Valk PG, et al. Prevalence of physical symptoms of itch, pain and fatigue in patients with skin diseases in general practice. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(6):1346–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.