Summary

There is a current lack of effective mucosal vaccines against major gastroenteric pathogens and particularly against Helicobacter pylori, which causes a chronic infection that can lead to peptic ulcers and gastric cancer in a subpopulation of infected individuals. Mucosal CD4+ T‐cell responses have been shown to be essential for vaccine‐induced protection against H. pylori infection. The current study addresses the influence of the adjuvant and site of mucosal immunization on early CD4+ T‐cell priming to H. pylori antigens. The vaccine formulation consisted of H. pylori lysate antigens and mucosal adjuvants, cholera toxin (CT) or a detoxified double‐mutant heat‐labile enterotoxin from Escherichia coli (dmLT), which were administered by either the sublingual or intragastric route. We report that in vitro, adjuvants CT and dmLT induce up‐regulation of pro‐inflammatory gene expression in purified dendritic cells and enhance the H. pylori‐specific CD4+ T‐cell response including interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A), interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) and tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) secretion. In vivo, sublingual immunization led to an increased frequency of IL‐17A+, IFN‐γ + and TNF‐α + secreting CD4+ T cells in the cervical lymph nodes compared with in the mesenteric lymph nodes after intragastric immunization. Subsequently, IL‐17A+ cells were visualized in the stomach of sublingually immunized and challenged mice. In summary, our results suggest that addition of an adjuvant to the vaccine clearly activated dendritic cells, which in turn, enhanced CD4+ T‐cell cytokines IL‐17A, IFN‐γ and TNF‐α responses, particularly in the cervical lymph nodes after sublingual vaccination.

Keywords: cytokines, dendritic cells, mucosa, T cells, vaccination

Abbreviations

- CLN

cervical lymph node

- CT

cholera toxin

- DCs

dendritic cells

- dmLT

double mutant heat‐labile toxin from Escherichia coli

- IFN‐γ

interferon‐γ

- IL‐17A

interleukin‐17A

- MLN

mesenteric lymph node

- Th1

T helper type 1

- TNF‐α

tumour necrosis factor‐α

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection in the stomach is a common cause of peptic ulcer disease and is a strong risk factor for the development of gastric adenocarcinoma. Infection is characterized by gastritis that remains chronic for decades, with an influx of immune cells such as dendritic cells (DCs), M1 and M2 macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes.1 The recruited immune cells secrete a range of pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin‐12p40 (IL‐12p40), IL‐1β, tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) and IL‐17A. Studies in the H. pylori mouse model have shown that mucosal vaccination with H. pylori antigens and a mucosal adjuvant results in a 10‐ to 100‐fold reduction in bacterial load compared with unvaccinated mice.2 To date the essential requirements for successful vaccination against H. pylori infection have been reported to be CD4+ T cells, functional leptin receptor3 and IL‐17A,4, 5, 6 but not antibodies or neutrophils.7, 8 Clearly, we need to improve our understanding of how CD4+ T cells are induced at the site of immunization, and how the bacteria in the stomach can be safely eliminated in symptomatic individuals. However, we still lack studies addressing the importance of the adjuvant and site of mucosal immunization on the activation of CD4+ T cells and cytokine production.

The intragastric and sublingual (under the tongue) routes of mucosal immunization are both attractive routes for vaccination against H. pylori infection because of their ability to induce protection and mucosal cytokine responses.4, 9, 10 In addition, the advantage of the mucosal route of vaccination is that it is needle‐free, reducing infection risks and costs of delivery. The sublingual route of immunization has recently received attention as an alternative to the intranasal route for inducing mucosal immune responses.11 The cervical lymph nodes (CLN) are the draining lymph nodes for the sublingual route of immunization. In mice, the sublingual mucosa is composed of a dense network of dendritic‐like cells of which the majority are thought to be MHC‐II+ mature DCs.12 Local administration of the model antigen ovalbumin together with the adjuvant cholera toxin (CT) has been shown to recruit MHC‐II+ DCs to the sublingual mucosa as well as effectively prime naive CD4+ T cells in the CLN promoting mucosal and systemic mixed T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 responses.12, 13 In addition, recent studies have shown that as a site of vaccination, the sublingual mucosa can induce T effector cells that then can migrate to other mucosal sites such as the genital tract, lungs, small intestine and stomach to perform their effector functions.11, 14, 15

The draining lymph nodes for the gastrointestinal tract are mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN). Specific subsets of DCs in the Peyer's patches can take up antigen and migrate to the MLN for presentation and activation of CD4+ T cells.16 After activation and differentiation, the CD4+ cells guided by expression of adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors can migrate back to the stomach, small or large intestine lamina propria and perform effector functions. The gastrointestinal tract is also the main site for induction of tolerance to food antigens and so a combination of antigen and a mucosal adjuvant is essential for overcoming the intrinsically suppressive environment and inducing protective CD4+ T‐cell immune responses against H. pylori infection.10

Indeed, we and others have shown in the H. pylori mouse model that neither antigens nor adjuvants alone induce any immune responses to H. pylori antigens, or protection against challenge with live bacteria.2 The mucosal adjuvant CT is widely used in animal models as a reference standard, for its ability to induce strong mucosal responses that are protective against H. pylori infection specifically due to the expansion of Th1 and Th17 cells to co‐administered antigens.4, 5, 7 Intense research efforts in the past few years have focused on developing detoxified enterotoxins and evaluating their potential as mucosal adjuvants.17 These include among others, the double‐mutant heat‐labile toxin (dmLT) from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and the multiple‐mutant cholera toxin.18, 19 Indeed, dmLT can induce strong mucosal immune responses to H. pylori antigens and protection against infection in the mouse model, and is safe for use in humans – as seen in a Phase I trial for an oral vaccine.20, 21, 22

Our previous studies in the H. pylori immunization model have shown that the sublingual route of immunization is dose sparing for the vaccine antigen and adjuvant compared with immunization via the intragastric route.4, 10, 20, 23, 24 We now report that, in vitro, when DCs isolated from the CLN or MLN are pulsed with H. pylori antigens and CT and dmLT adjuvants, they are able to effectively activate H. pylori‐specific CD4+ T cells and induce their cytokine secretion. However, when studying mucosal priming in vivo the sublingual route of immunization had a tendency to induce a stronger cytokine response from CD4+ T cells in the CLN compared with the response seen in the MLN after intragastric immunization. Sublingually immunized mice challenged with live H. pylori also had a tendency for an increased staining for IL‐17A+ cells in the stomach compared with intragastrically immunized mice. Our studies indicate that the dose‐sparing effects of the sublingual route of immunization might be related to the induction of a stronger cytokine secretion and earlier kinetics of a CD4+ T‐cell response compared with the response induced by the intragastric route. The results presented in this study have potential implications for the design of an H. pylori vaccine and choice of administration route for Phase I clinical trials.

Materials and methods

Mice

Six‐ to eight‐week‐old, specific‐pathogen‐free, female C57BL/6 mice and ovalbumin T‐cell transgenic mice (OT‐II) (from in‐house breeding), which are homozygous for a transgene that encodes a T‐cell receptor specific for chicken ovalbumin (amino acids 323–339), presented on the MHC class II molecule I‐Ab were used. Age‐matched, specific‐pathogen‐free wild‐type female C57BL/6 mice were bought from Taconic (Ejby, Denmark). The mice were housed in microisolators at the Laboratory for Experimental Biomedicine during the time of the study. All experiments were approved by the ethics committee for animal experiments (Gothenburg, Sweden).

H. pylori lysate antigens preparation and immunizations

Helicobacter pylori lysate antigens from the strain Hel 305 (CagA+, VacA+) isolated from a patient with a duodenal ulcer was prepared as previously described.10 The protein content of the lysate antigens was measured using the non‐interfering protein assay kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). The antigen preparation was aliquoted and stored at −70° until further use and not subjected to multiple freeze–thaw cycles. Aliquots of H. pylori lysate antigens were freeze‐dried and reconstituted to a protein concentration of 20 mg/ml to reduce the volume used for the sublingual immunizations. The same dose of antigens was used for intragastric immunization as for sublingual immunizations and administered together with sodium bicarbonate buffer. Lyophilized CT from Vibrio cholera (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was reconstituted in sterile distilled water to a concentration of 1 mg/ml (and stored in aliquots at −70° until further use). Lyophilized dmLT (R192G/L211A) from E. coli was prepared as described elsewhere,25 was reconstituted in sterile distilled water to a concentration of 1 mg/ml and stored at 4° until further use.

Cultivation of H. pylori SS1 used for infection of sublingually immunized mice

Helicobacter pylori Sydney strain 1 (SS1) was cultured on Colombia iso‐agar plates for 2–3 days and then cultured overnight in Brucella broth (Becton, Dickinson and Company (BD), Sparks, MD) in a microaerophilic environment as described previously.10 The optical density was adjusted to 1·5 and viability of the bacteria was ensured by visualization under a microscope, and 300 μl was administered intragastrically to each mouse. Each dose corresponded to approximately 3 × 108 viable bacteria.

Cultivation of Flt3 ligand tumour cells used for injection and expansion of CD11c+ DCs in vivo

Flt3L‐secreting B16‐F10 melanoma was obtained from Nicolas Mach26 and was stored in liquid nitrogen, thawed and cultured for 2–3 days in a 25‐mm2 flask in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Biochrome, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal calf serum (Sigma), 50 μm 2‐mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 1 mm l‐glutamine (Biochrome) and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma) (Iscove's complete medium) at 37° and in 5% CO2 atmosphere. At confluence, cells were collected, washed and resuspended in fresh Iscove's complete medium and cultivated further for 2–3 days in a 75‐mm2 cell culture flask. On the day of injection, the cells were collected, washed and resuspended in fresh Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium without supplements and counted. Each mouse was administered a total of 1 × 106 cells injected subcutaneously. The mice were palpated to follow tumour growth and euthanized when the tumour size had reached 100 mm3.

Dendritic cell culture, RNA extraction and cDNA preparation for PCR array

Dendritic cell culture

Single‐cell suspensions were prepared from the spleens of Flt3L‐treated mice. CD11c+ cells were enriched from total spleen cells by CD11c+ positive selection using magnetically labelled MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The purity of the CD11c DCs in repeated isolations was typically > 90%. CD11c+ DCs cultured for RNA extraction were seeded (4 × 106 DCs per well) in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml CT or dmLT and cultured for 4 hr in Iscove's complete medium at 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were collected after incubation, thoroughly washed to remove all culture medium and additives and resuspended in 350 μl RLT lysis Buffer (Qiagen, Duesseldorf, Germany) for downstream RT‐PCR application. The samples were stored at −70°.

RNA extraction and cDNA preparation

RNA was extracted by using a shredder column and RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and purity and concentration were measured using the fluorospectrophotometer NanoDrop ND‐1000 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Quantitect kit (Qiagen).

RT‐PCR array

Complementary DNA (2 μg) was run in 96‐well array plates (Mouse dendritic and antigen‐presenting cell array, SA Biosciences/Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions using the 7500 RT‐PCR Applied Biosystems system and 2× Power SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). An average of the housekeeping genes β‐actin, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), β2‐microglobulin, β‐glucuronidase and heat‐shock protein 90αb1 was used as control. The difference between the sample gene and the average from the housekeeping genes (ΔCT value) was obtained and the relative fold change and expression were calculated by 2ΔCT. The values for all samples were compared with non‐stimulated cells and expressed as fold‐change from non‐stimulated samples. Validation was carried out with RNA (2 μg) that was first reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Quantitect kit (Qiagen). The samples were run in 96‐well plates using the standard amplification settings for the 7500 RT‐PCR system and 4 μl cDNA, 10 μl 2× Power SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems) and 1 μl of gene‐specific oligonucleotide primers (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany). Each sample was run in duplicate and β‐actin was used as a housekeeping gene control for the validation experiment. The difference between the sample gene and β‐actin (ΔCT value) was obtained and the relative expression was calculated by 2ΔCT. The values for all samples were calculated as fold change from non‐stimulated cells.

Co‐culture of DCs pulsed with ovalbumin with ovalbumin transgenic CD4+ T cells

Preparation and stimulation of DCs

Single‐cell suspensions were prepared from the MLN and CLN of Flt3L‐treated wild‐type mice. CD11c+ cells were enriched from total MLN and CLN cells by CD11c+ positive selection using magnetically labelled MACS beads (Miltenyi). Enriched CD11c+ DCs from MLN or CLN were incubated alone or in the presence of 2 mg/ml ovalbumin grade VII (Sigma) together with or without 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−5, 10−7 μg/ml of CT or dmLT and cultured for 4 hr in Iscove's complete medium. After incubation the cells were washed thoroughly three or four times to completely remove any residual antigen or adjuvant.

Preparation of OT‐II T CD4+ T cells and co‐culture with stimulated DCs

Spleen CD4+ T cells ovalbumin transgenic (OT‐II) mice were prepared using a CD4 positive selection kit (Miltenyi). CD4+ cells in repeated isolations were typically > 90%. Stimulated or unstimulated DCs were seeded (1 × 104 DCs per well) together with CD4+ OT‐II spleen T cells (1 × 105 per well) in a sterile 96‐well plate and left for 5 days in 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Supernatants were collected and stored at −70° for subsequent cytokine analysis. To determine proliferation (radioactive thymidine incorporation assay), the cells were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Amersham Bioscience, Buckinghamshire, UK) for the last 6–8 hr of culture. The cellular DNA was collected with a cell harvester (Skatron) on glass fibre filters (Perkin Elmer, Upplands Väsby, Sweden) and assayed for 3H incorporation using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman, LKB, Bromma, Sweden).

Co‐culture of DCs pulsed with H. pylori antigens and CD4+ T cells from sublingually immunized mice

Preparation and stimulation of DCs

Enriched CD11c+ DCs from MLN or CLN of Flt3L‐injected mice were incubated alone or in the presence of H. pylori strain Hel 305 lysate antigens (20 μg/ml), together with or without 10−3 μg/ml of CT or dmLT and cultured for 4 hr in Iscove's complete medium. After incubation, cells were washed thoroughly to completely remove any residual antigens or adjuvant.

Preparation of CD4+ T cells and co‐culture with stimulated DCs

The MLN was isolated from mice sublingually immunized with H. pylori lysate antigens and 10 μg CT and infected with H. pylori SS1. The CD4+ T cells from the MLN were enriched by CD4+ positive selection using magnetically labelled MACS beads (Miltenyi). Stimulated or unstimulated DCs were seeded (1 × 104 DCs per well) together with CD4+ H. pylori‐specific MLN T cells (1 × 105 per well) in a sterile 96‐well plate and left for 5 days in 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Supernatants were collected and stored at −70° for subsequent cytokine analysis. Proliferation was determined by the radioactive thymidine incorporation assay.

Cytokines analysed by Cytometric Bead Array Flex Set

Supernatant from the proliferation assay was analysed for cytokines IL‐17A, IFN‐γ and TNF‐α using Cytometric Bead Assay Flex Set beads according to the manufacturer's protocol (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Sublingual or intragastric immunization and treatment with FTY720

Mice were prophylactically immunized via the sublingual or intragastric route with 400 μg H. pylori lysate antigens and 10 μg of adjuvant CT or dmLT as previously described.20 FTY720 (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI), a structural analogue of sphingosine and potent agonist of the sphingosine‐1‐phosphate receptors, was administered to prevent the egress of lymphocytes from the lymph nodes after immunization. FTY720 was diluted to 0·5 mg/ml in physiological saline and each mouse was administered a dose 0·025 mg intraperitoneally. The FTY720 treatment was started 1 day before immunization and continued for 6 days and the mice were euthanized on day 7 after immunization. To ensure that the FTY720 treatment was effective, blood was collected on day 3 and day 7 after immunization stained for lymphocytes CD3, CD4 and CD8 and analysed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis

The MLN and CLN cells from mice immunized by the sublingual and intragastric routes and treated with FTY720 were isolated and single cell suspensions were prepared. For cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with 20 ng/ml PMA (Sigma) and 1 μg/ml Ionomycin (Sigma) in Iscove's complete medium for 2 hr at 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 2 hr, 10 μg/ml Brefeldin A (Sigma) in Iscove's complete medium was added to the cells and left for a further 2 hr at 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Surface and intracellular staining was carried out using anti‐mouse CD3‐Peridinin chlorophyll protein, CD4‐Alexa Fluor 700, TNF‐α‐Phycoerythrin‐Cy7 and IFN‐γ‐allophycocyanin (all BD Biosciences) and IL‐17A‐FITC (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and a Live/Dead Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit was used to stain dead cells before fixation (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The stained cells were acquired using the LSR‐II Flow Cytometer (BD) and analysed using the flowjo software version 7.6.5 (FlowJo, Ashland, OR).

Immunohistochemistry staining for IL‐17A

A vertical strip from the entire stomach taken from sublingually immunized mice 3 weeks after infection was frozen in embedding medium OCT (Histolab, Gothenburg, Sweden) and the frozen blocks were stored at −70° until further use. Sections (7 μm) were cut and allowed to dry followed by fixation with 100% ice‐cold acetone. Sections were permeabilized with 0·5% Triton X‐100 (Sigma) and then blocked with 10% goat serum (Sigma) and Fc‐γ receptor block. The blocking solution was blotted out and primary antibody rat anti‐mouse IL‐17A‐FITC (eBioscience) or rat isotype‐FITC control (eBioscience) was added in 0·1% Triton X‐100 and incubated at room temperature. Sections were washed in PBS and mounted using a mounting medium prolong® gold antifade (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) containing DAPI. Interleukin‐17A staining in the lamina propria was then visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplex 2). Images were analysed using the biopix software (Biopix, Göteborg, Sweden) for histological quantification of IL‐17A+ cells and compared with the total area of lamina propria in each stomach section.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (anova) with Sidak's post‐test was used to compare multiple groups of mice using graphpad prism software version 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). For all tests, a P‐value of < 0·05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Adjuvants CT and dmLT induce comparable in vitro gene expression of pro‐inflammatory molecules in DCs

Our aim was to study the mechanisms of mucosal adjuvant function and particularly their influence on DCs as they are among the first cells to come in contact with the antigen and adjuvant at the site of immunization and also to directly influence T‐cell priming. CD11c+ DCs were isolated using MACS beads from the spleen of mice injected previously with Flt3L‐secreting melanoma cells and stimulated in vitro with 1 μg/ml each of CT or dmLT. The DCs were collected after 4 hr of stimulation with the adjuvants and gene expression in the cells was evaluated using the Qiagen mouse dendritic and antigen‐presenting cell PCR array. Compared with unstimulated DCs, stimulation of DCs in the presence of 1 µg/ml of CT or dmLT up‐regulated activation markers such as CD80 and CD86 to a similar extent (2‐ and 1·5‐fold, respectively) (Table. 1). In addition, CXCL2 and thrombospondin‐1 was highly up‐regulated after stimulation with CT (11‐fold and 67‐fold, respectively) and to a lesser extent after stimulation with dmLT (2‐fold and 29‐fold, respectively) (Table 1). Cholera toxin also induced higher up‐regulation of IL‐6 compared with dmLT, whereas dmLT stimulated elevated up‐regulation of IFN‐γ compared with CT (Table 1). Several genes were also down‐regulated compared with unstimulated cells, for example chemokine receptors, toll‐like receptors and CD4 (Table 2). Validation of the PCR array results was performed using in‐house primers for CXCL2, IL‐6 and IFN‐γ that confirmed our results of the PCR array (data not shown). Hence, CT and dmLT induced elevated gene expression of activation markers, chemokines and cytokines in DCs, which might explain the potent adjuvant activity in vivo.

Table 1.

Gene expression in DCs stimulated with adjuvant; up‐regulated genesa

| Gene | 1 μg CT | 1 μg dmLT | Responding cell population |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCR1 | 2·0 | 1·4 | T cells |

| CD80 | 2·0 | 1·5 | T cells |

| CD86 | 2·0 | 1·5 | T cells |

| CXCL2 (Mip‐2α) | 11·0 | 2·2 | Polymorphonuclear cells, stem cells |

| FcγR1 (CD64) | 3·0 | 1·4 | Macrophages, Monocytes |

| IFNγ | 3·5 | 4·8 | Macrophages, T and B cells, natural killer cells |

| IL6 | 6·0 | 2·7 | B cells, neutrophils |

| TSP1 (Thrombospondin‐1) | 67·0 | 29·0 | Macrophages, endothelial cells, polymorphonuclear cells |

| Tnfsf11 (RANKL) | 2·6 | 2·9 | Osteoclast cells, stromal cells |

CT, cholera toxin; dmLT, double mutant heat‐labile toxin from Escherichia coli.

The difference between housekeeping genes and the target gene (∆CT) was determined, and the relative expression was calculated using the formula 2∆CT. Values are then expressed as fold change compared with dendritic cells stimulated without adjuvant.

Table 2.

Gene expression in DCs stimulated with adjuvant; down‐regulated genesa

| Gene | 1 μg CT | 1 μg dmLT | Responding cell population |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCL8 | 0·4 | 0·6 | Monocytes |

| CCR2 | 0·2 | 0·2 | Monocytes |

| CCR9 | 0·3 | 0·5 | T cells in small intestine and colon |

| CD1d1 | 0·3 | 0·6 | Natural killer T cells |

| CD209α | 0·4 | 0·5 | Monocytes |

| CD4 | 0·4 | 0·4 | T cells |

| CD40L | 0·2 | 1·0 | T cells |

| CXCL12 | 0·5 | 0·9 | Lymphocytes |

| ICAM2 | 0·4 | 0·4 | T cells |

| IL16 | 0·1 | 0·5 | CD4+ expressing cells |

| IL2 | 0·1 | 0·6 | T cells, natural killer cells, B cells |

| TLR1 | 0·3 | 0·4 | Monocytes, macrophages, B cells |

| TLR2 | 0·4 | 0·8 | Monocytes, macrophages, mast cells |

| TLR7 | 0·2 | 0·3 | Monocytes, macrophages, B cells |

| TNF | 0·5 | 0·6 | Monocytes |

CT, cholera toxin; dmLT, double mutant heat‐labile toxin from Escherichia coli.

The difference between housekeeping genes and the target gene (∆CT) was determined, and the relative expression was calculated using the formula 2∆CT. Values are then expressed as fold change compared with dendritic cells stimulated without adjuvant.

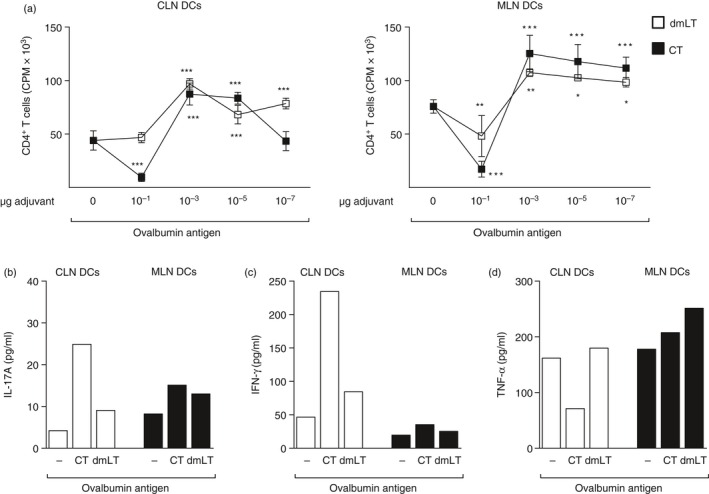

In vitro activation and proliferation of CD4+ T cells from CLN and MLN is dependent on the dose of adjuvant and type of antigen

We next wanted to address the induction and priming of CD4+ T‐cell responses, by in vitro activated DCs from the CLN and MLN in the presence or absence of adjuvants CT and dmLT. First, the optimal dose of adjuvant required to stimulate CD4+ T‐cell responses was evaluated by using ovalbumin transgenic CD4+ T cells (OT‐II) and DCs isolated from CLN and MLN of previously Flt3L melanoma‐injected mice, pulsed in vitro with 10−1, 10−3, 10−5 and 10−7 μg/ml of CT or dmLT together with ovalbumin for 4 hr. The DCs were then thoroughly washed, counted and co‐cultured with purified CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleen of OT‐II mice and proliferative responses were measured. The results showed that a concentration of 10−1 μg/ml CT or dmLT was significantly anti‐proliferative to the CD4+ T cells in the presence of CT but not dmLT. The presence of antigen and 10−3, 10−5 or 10−7 μg/ml of CT or dmLT induced significantly higher proliferative responses by the CD4+ T cells compared with the response to ovalbumin alone without adjuvant (Fig. 1a). The CD4+ T‐cell proliferation induced by DCs isolated from CLN or MLN were comparable (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

In vitro proliferation of ovalbumin transgenic CD4+ T cells from mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and cervical lymph node (CLN) is dependent on the dose of adjuvant. Mice were implanted subcutaneously with Flt3L‐secreting melanoma cells and killed when the tumour reached 100 mm3 in size. Dendritic cells (DCs) were isolated from the CLN and MLN and pulsed in vitro with 10−1, 10−3, 10−5 and 10−7 μg/ml of cholera toxin (CT) or double mutant heat‐labile toxin from Escherichia coli (dmLT) together with 2 mg/ml ovalbumin for 4 hr. DCs were subsequently thoroughly washed and co‐cultured with isolated spleen CD4+ OT‐II cells for 5 days and (a) proliferative response of the CD4+ T cells was measured in counts per minute (cpm) of incorporated radioactive thymidine and (b–d) the cytokines (b) interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A), (c) interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) and (d) tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) (pg/ml), were measured in culture supernatants for concentrations of adjuvants 10−3 μg/ml of CT or dmLT, or ovalbumin only. Data are shown as (a) mean values of counts per minute of incorporated radioactive thymidine in six wells representative of two independent experiments. (b–d) Cytokines in pg/ml of pooled wells from the culture conditions as above. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

Secretion of IL‐17A, IFN‐γ and TNF‐α cytokines by the proliferated CD4+ T cells was evaluated. As the strongest proliferative response by the CD4+ T cells was seen in the presence of DCs pulsed with 10−3 μg/ml of adjuvant and ovalbumin, the cytokine level in the supernatant from this particular culture was analysed. In the DCs isolated from the CLN but not MLN, enhanced secretion of IL‐17A and IFN‐γ by the CD4+ T cells was seen in the presence of CT and ovalbumin. The IL‐17A levels were low in the culture supernatants despite CT and dmLT inducing strong proliferative responses (Fig. 1b–d).

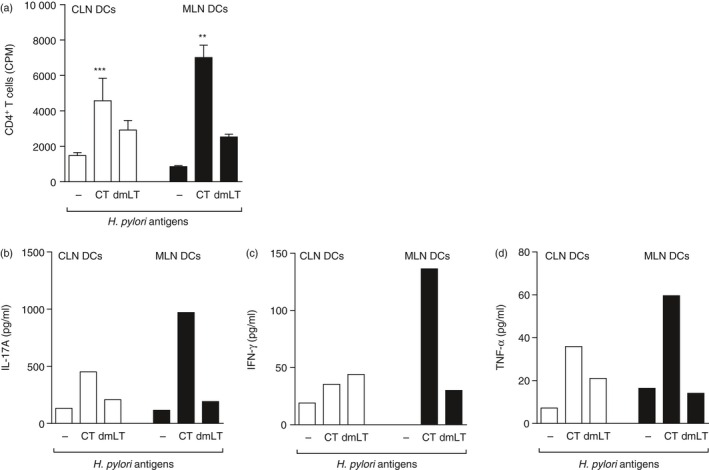

We next evaluated DC priming of CD4+ T‐cell responses to H. pylori lysate antigens. The DCs isolated from CLN and MLN of Flt3L melanoma‐implanted mice were pulsed for 4 hr in vitro with 10−3 μg/ml of CT or dmLT together with 20 µg/ml H. pylori lysate antigens. The DCs were then washed thoroughly and mixed with responder CD4+ T cells isolated from the MLN of H. pylori‐infected sublingually immunized mice. The results showed that DCs pulsed with CT induced a significantly stronger CD4+ T‐cell proliferative response than DCs pulsed with dmLT, irrespective of whether they were isolated from CLN or MLN (Fig. 2a). Cytokine analysis was carried out in the supernatants, which showed not only high levels of IL‐17A but also of IFN‐γ and TNF‐α, particularly in cultures containing DCs isolated from the MLN (Fig. 2b–d).

Figure 2.

Dendritic cells (DCs) isolated from the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) or cervical lymph nodes (CLN) and pulsed with Helicobacter pylori lysate antigens together with adjuvant cholera toxin (CT) induce CD4+ T‐cell activation and cytokine secretion. Groups of mice were sublingually immunized with H. pylori lysate antigens and CT and then challenged with live H. pylori bacteria. Three weeks post challenge mice were killed and CD4+ T cells were isolated from MLN. DCs were isolated from the CLN and MLN of mice implanted subcutaneously with Flt3L‐secreting melanoma cells and pulsed in vitro with 10−3 μg/ml of CT or double mutant heat‐labile toxin from Escherichia coli (dmLT) together with 20 μg heat‐treated H. pylori lysate antigens for 4 hr. DCs were also pulsed with H. pylori lysate antigens without adjuvant. Pulsed DCs were washed thoroughly and co‐cultured for 5 days with the MLN CD4+ T cells isolated from sublingual immunized mice and (a) proliferative response of the T cells were measured in counts per minute (cpm) of incorporated radioactive thymidine and (b) interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A), (c) interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) and (d) tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF α) was measured in culture supernatants and shown as pg/ml for concentrations of adjuvants 10−3 μg/ml of CT or dmLT or only H. pylori lysate antigens. Data are shown as (a) mean values of counts per minute of incorporated radioactive thymidine in three wells representative of two independent experiments and (b–d) cytokines in pg/ml of pooled wells from the different culture conditions as in (a) **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

In summary in the presence of antigen and 10−3 μg/ml of CT or dmLT in culture, enhanced proliferation of CD4+ T cells could be observed with high IL‐17A cytokine secretion, particularly in response to H. pylori antigen.

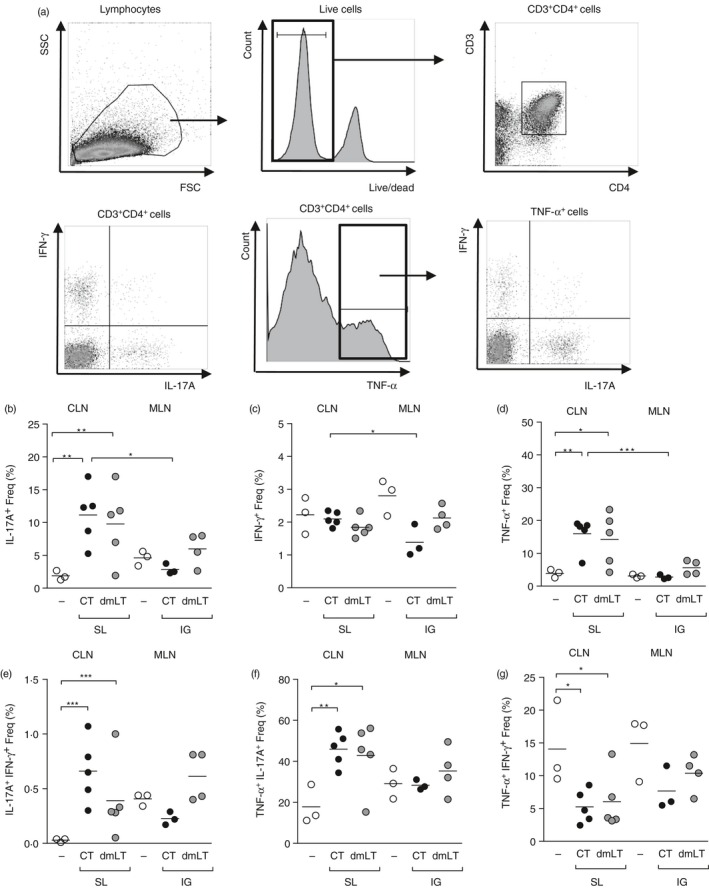

Enhanced in vivo cytokine responses in the CLN after sublingual immunization compared with MLN after intragastric immunization

Although our in vitro results gave us some indication of the effects of adjuvants on priming CD4+ T‐cell responses, we were interested in relating it to in vivo CD4+ T‐cell priming by H. pylori antigens in combination with adjuvants. FTY720 was administered intraperitoneally to prevent the exit of lymphocytes from the lymph nodes, so that the immune responses could be studied in isolation. Mice were immunized sublingually or intragastrically with H. pylori lysate antigens and CT or dmLT. The CLN and MLN were collected 7 days after immunization and single‐cell suspensions were prepared. After a brief stimulation with PMA and ionomycin, flow cytometric staining and analysis were performed for cell surface markers and intracellular cytokines IL‐17A, IFN‐γ and TNF‐α. Live cells were gated for CD3+ and CD4+ T cells and the cytokine secretion was analysed in the gated population in the different groups of mice. Sublingual immunization with CT induced a significant increase (P < 0·05) in the frequency and number of T cells secreting IL‐17A and TNF‐α and double‐positive IL‐17A+ IFN‐γ + and TNF‐α + IL‐17A+ cells in CLN compared with cells isolated from the CLN of unimmunized naive mice (Fig. 3a–g and see Supplementary material, Fig. S1a–f). Remarkably, sublingual immunization with dmLT also induced a significant increase (P < 0·05) in the frequency and number of CD4+ T cells secreting IL‐17A, TNF‐α and double‐positive IL‐17A+ IFN‐γ + and TNF‐α + IL‐17A+ cells in CLN compared with cells isolated from the CLN of unimmunized naive mice (Fig. 3a–g and see Supplementary material, Fig. S1a–g). Finally, intragastric immunization with H. pylori antigens and dmLT induced a modest up‐regulation of IL‐17A, TNF‐α and double‐positive cytokine‐secreting cells in the MLN compared with responses in CLN after sublingual immunization.

Figure 3.

Increased cytokine response in the cervical lymph nodes after sublingual immunization. Groups of mice were administered with FTY720 intraperitoneally 1 day before immunization and thereafter every 48 hr until death. Mice were sublingually or intragastrically immunized with Helicobacter pylori lysate antigen and cholera toxin (CT) or double mutant heat‐labile toxin from Escherichia coli (dmLT) or left unimmunized. Seven days after immunization, mice were killed and CLN was taken from sublingually immunized mice and MLN from intragastrically immunized mice and single‐cell suspensions were prepared. Cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin. (a) FACS analysis of cells gated on live, CD3+ CD4+ cells. Frequency (%) of cells positive for (b) interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A+), (c) interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ +), (d) tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α +), (e) IL‐17A+ IFN‐γ +, (f) TNF‐α + IL‐17A+, or (g) TNF‐α + IFN‐γ +. Each symbol represents an individual mouse; data pool two independent experiments with two or three mice/group. White circles represent naive mice, black circles represent mice immunized with lysate and CT and grey circles represent mice immunized with lysate and dmLT. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 and ***P < 0·001.

In the CLN of sublingually immunized mice with H. pylori lysate antigens and CT a significant (P < 0·05) increase in the total number of CD3+ CD4+ T cells was also observed compared with unimmunized naive mice (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1g). Finally, Foxp3 expression in total cells isolated from MLN and CLN of immunized mice was determined and we found an up‐regulation of Foxp3 in the total MLN but not CLN cells from immunized compared with unimmunized mice (data not shown). In summary, our results showed that vaccination with H. pylori antigens and either CT or dmLT induced a pro‐inflammatory cytokine secretion by CD4+ T cells in the CLN after sublingual immunization.

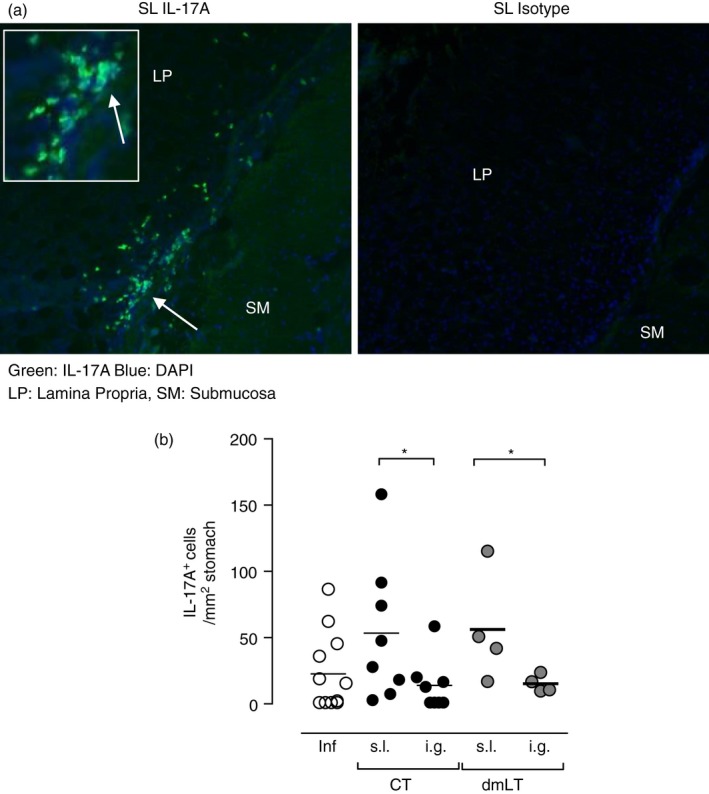

Sublingual immunization with H. pylori lysate antigens induces an IL‐17A response in the stomach

Our in vivo results gave us insight into the cytokine response by CD4+ T cells after immunization in the draining lymph nodes and noticeably after sublingual immunization the IL‐17A response was elevated in the CLN. Hence, we wanted to investigate whether the primed cells migrate to the stomach of mice after infection. Mice were immunized either sublingually or intragastrically, with H. pylori lysate antigens and CT or dmLT and challenged 2 weeks after the last immunization with live H. pylori. Three weeks post challenge the mice were killed and the stomach was taken for analysis of IL‐17A in the stomach by immunohistochemistry. IL‐17A+ cells in the gastric lamina propria mucosa was quantified in individual mice and related to per mm2 area of the stomach. The IL‐17A+ staining in all mice was mostly restricted to the lamina propria and so to be able to compare between groups of mice, only these cells were counted and not the few cells residing at the epithelium or submucosa of the stomach (Fig. 4a). The frequency of IL‐17A+ cells in the stomach was significantly higher (P < 0·05) in sublingually immunized compared with intragastrically immunized mice when using either CT or dmLT as adjuvant (Fig. 4b). This suggests that the IL‐17A+ cells can be detected in the stomach particularly in sublingually immunized mice.

Figure 4.

Sublingual (s.l.) immunization with Helicobacter pylori lysate antigens induces an interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A) cytokine response in the lamina propria of the stomach after challenge. Groups of mice were immunized using the sublingual or intragastric (i.g.) route with H. pylori lysate antigens and 10 μg cholera toxin (CT) or double mutant heat‐labile toxin from Escherichia coli (dmLT) and challenged with live H. pylori bacteria. At 3 weeks post challenge the mice were killed and the stomach tissue was frozen and sectioned for immunohistochemistry staining as described in the Materials and methods section. (a) Interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A) staining in mice immunized with CT and dmLT. Left: Representative staining in the stomach of a mouse sublingually immunized with H. pylori lysate antigens and CT (sublingual), IL‐17A in green and nuclear staining (DAPI) in blue and Right: isotype control staining from the same tissue. (b) IL‐17A+ cells in the lamina propria per mm2; each dot represents an individual mouse. Data pool 2 independent experiments with two to five mice/group. White circles represent infected unimmunized controls, black circles represent mice immunized with lysate and CT and grey circles represent mice immunized with lysate and dmLT. *P < 0·05.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to elucidate the mechanisms of T‐cell priming and cytokine induction in the draining lymph nodes after mucosal immunization; CLN for the sublingual route and MLN for the intragastric route, and compare the effect of using CT or dmLT as adjuvants together with an H. pylori vaccine. We first evaluated the direct effect of adjuvant CT or dmLT on DC activation and T‐cell priming by assessing gene expression in DCs in response to the adjuvants. Both adjuvants induced high gene expression of pro‐inflammatory molecules compared with unstimulated DCs, although CT induced higher gene expression overall than dmLT. One of the genes that was highly up‐regulated in the DCs pulsed with CT and to a lesser extent dmLT was that for thrombospondin‐1. Thrombospondin‐1 is a potent activator of neutrophils and plays an important role in inflammatory responses, angiogenesis, platelet aggregation, vasodilatation, leucocyte migration and chemotaxis.27 Preliminary results in our laboratory have shown an up‐regulation in the frequency of neutrophils in the blood after sublingual immunization with lysate antigens and CT; suggesting that thrombospondin‐1 might have effects in mobilizing neutrophils from the bone marrow to the site of inflammation (S. Akhtar, F. Jeverstam, T. Bhuiyan and S. Raghavan, unpublished). In addition, CT and dmLT also enhanced the gene expression of co‐stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 and cytokines IL‐6 and IFN‐γ, suggesting that the DCs exposed to the adjuvant are poised to respond to the antigen and initiate an antigen‐specific CD4+ T‐cell response in the draining lymph nodes. The in vitro effects of CT and other adjuvants have been studied in follicular DCs and B cells but the effect of CT and dmLT on DCs had not been studied side by side, although there are several studies showing in vitro activation of DCs in humans and mice by H. pylori‐derived antigens.28, 29

Co‐culture of DCs pulsed with antigen and adjuvant with CD4+ T cells showed clearly that both CT as previously known,30 and dmLT were anti‐proliferative to T cells at high concentrations and careful titration of the adjuvant is necessary to observe the potentiating effects of the adjuvants on the CD4+ T‐cell response. The in vitro anti‐proliferative effects of CT have been previously shown to the result of the induction of second messenger cAMP in the cells.31 However, it was noteworthy that dmLT, which is a detoxified molecule, was anti‐proliferative to CD4+ T cells at the highest concentration, indicating that the adjuvant effect and activation of DCs might be related to the low amounts of cAMP induced as reported by Norton et al. in Caco‐2 cell lines.18 When using ovalbumin‐specific transgenic CD4+ T cells, and DCs pulsed with ovalbumin and CT or dmLT, the proliferative response and cytokine secretion by the T cells was similar whether the DCs priming the T cells were isolated from the MLN or CLN. A difficulty in studying the function of DCs in vitro in culture is that they are in isolation and can lose the signals and cytokines that are provided by accessory cells in vivo, which might have been very different in the CLN and MLN. In early experiments, we immunized mice sublingually or intragastrically with ovalbumin and CT or dmLT and isolated the DCs from the draining lymph nodes for stimulation of CD4+ OT‐II T cells in vitro. However, the OT‐II CD4+ T cells failed to respond after co‐culture with DCs isolated in vivo from the immunized mice, possibly due to the low frequency of DCs that had specifically taken up ovalbumin antigen (data not shown).

By analysing the CD4+ T cells in vivo in the CLN and MLN after sublingual or intragastric immunization, respectively, we could further show that cytokine responses are particularly increased in the CLN after sublingual immunization. Interestingly, a selective up‐regulation of the frequency of IL‐17A‐ and TNF‐α‐secreting CD4+ T cells was seen. We have previously shown that the sublingual route of immunization induces a strong IL‐17A response in the stomach when using H. pylori lysate antigens and either CT or dmLT as adjuvants.20 We can now show that the induction of the IL‐17A secretion by CD4+ T cells takes place in the CLN after sublingual immunization. In general, H. pylori lysate antigens and adjuvant CT induced a stronger cytokine secretion from CD4+ T cells compared with adjuvant dmLT in the CLN whereas very weak responses were detected in the MLN. Preliminary results in our laboratory have shown that, when the dose of antigens and adjuvant was increased for intragastric immunization, similar protection against H. pylori infection could be seen as for the lower dose used for sublingual immunization (F. Jeverstam, M. Blomquist, S. Karlsson, J. Tobias, J. Holmgren and S. Raghavan, unpublished). The sublingual route of immunization can therefore be regarded as dose sparing in the H. pylori vaccination model.

Mice fed CT intragastrically have been shown to have MHC‐II+ DC numbers increased in the follicle‐associated epithelium of the Peyer's patches also within 1 hr and to decline between 8 and 12 hr, promoting the migration of DCs from the subepithelial dome underlying the follicle‐associated epithelium to the T‐cell and B‐cell areas.32 Hence, during immunization, in addition to activating DCs, CT might increase the possibility for DCs to capture the incoming antigens due their localization and subsequent priming of the CD4+ T‐cell response.33 However, we observed that the cytokine response (both IL‐17A and IFN‐γ) by the CD4+ T cells in MLN after intragastric immunization was relatively low suggesting that that either the Peyer's patches or possibly the paragastric lymph nodes are the priming site for vaccine‐induced T‐cell responses. CD4+ T cells isolated from the paragastric lymph nodes of BALB/c mice vaccinated with a recombinant attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium‐based vaccine can proliferate in response to H. pylori antigens in vitro.9 A strong cytokine response was found in the CLN after sublingual immunization in this study, which could not be detected in the MLN early after intragastric immunization, suggesting that cytokine secretion by CD4+ T cells in the MLN is either weak or takes place at a different location or time‐point.

To study the migration of IL‐17A‐secreting cells to the stomach, we analysed the staining pattern of the IL‐17A in mice immunized by the sublingual or intragastric route after challenge with H. pylori. In sublingually immunized mice there was an increase in the frequency of IL‐17A+ cells in the stomach lamina propria after infection. Given the well‐known importance of CD4+ T cells in vaccine induced protection against H. pylori, we expect that the IL‐17A‐secreting cells are Th17 cells; however, this is a subject of ongoing studies. Notably, the IL‐17A staining in the sublingually immunized mice was in close proximity to the epithelial cells, indicating that IL‐17A might have direct effects on the epithelial cells in inducing, for example, chemokines and anti‐microbial peptide secretion.34 This can be supported by a recent study showing that the combination of recombinant IL‐17A and IL‐22 can induce antimicrobial peptide and defensin production in human gastrointestinal epithelial cells as well as in mouse primary gastric epithelial cells.35 In addition, the same study showed that the combination of these two cytokines conferred increased killing of H. pylori in vitro in human cell lines.

In summary, our data confirm previous results that CT and dmLT have similar adjuvant potential and support them with the findings that they have similar effects on the gene expression in DCs, as well as the activation and priming of CD4+ T cells. However, at the same dose, immunization with either CT or dmLT induces a stronger cytokine response in the draining lymph node CLN after sublingual immunization compared with in the MLN after intragastric immunization. These studies provide a basis for making an informed choice when designing clinical trials of H. pylori vaccines.

Author contribution

LSO planned and performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper; FJ planned and performed the experiments and analysed the data; LY provided the Flt‐3L cells, critical advice and reagents, and reviewed the paper before submission; UAW provided crucial reagents, designed the flow cytometry panels, analysed the data and reviewed the paper before submission; AKW planned the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper; SR planned the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Total numbers of cytokine secreting cells are enhanced in the cervical lymph nodes after sublingual immunization.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from The Sahlgrenska Academy, The Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, through its support to the Mucosal Immunobiology and Vaccine Centre (MIVAC), The Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT), Swedish Cancer Foundation (Grant: 13/0411), Swedish Research Council (VR grant 348‐2014‐3071).

References

- 1. Raghavan S, Holmgren J, Svennerholm A‐M. Chapter 51 ‐ Helicobacter pylori Infection of the Gastric Mucosa In: Strober W, Russell MW, Kelsall BL, Cheroutre H, Lambrecht BN, eds. Mucosal Immunology (Fourth Edition). Boston: Academic Press, 2015: 985–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raghavan S, Quiding‐Järbrink M. Vaccination against Helicobacter pylori infection In: Backert S, Yamaoka Y, eds. Helicobacter pylori Research: From Bench to Bedside. Japan: Springer, 2016: pp. 575–603. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wehrens A, Aebischer T, Meyer TF, Walduck AK. Leptin receptor signaling is required for vaccine‐induced protection against Helicobacter pylori . Helicobacter 2008; 13:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flach CF, Ostberg AK, Nilsson AT, Malefyt Rde W, Raghavan S. Proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in the stomach correlates with vaccine‐induced protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in mice: an important role for interleukin‐17 during the effector phase. Infect Immun 2011; 79:879–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Velin D, Favre L, Bernasconi E, Bachmann D, Pythoud C, Saiji E, et al Interleukin‐17 is a critical mediator of vaccine‐induced reduction of Helicobacter infection in the mouse model. Gastroenterology 2009; 136:e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DeLyria ES, Nedrud JG, Ernst PB, Alam MS, Redline RW, Ding H, et al Vaccine‐induced immunity against Helicobacter pylori in the absence of IL‐17A. Helicobacter 2011; 16:169–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DeLyria ES, Redline RW, Blanchard TG. Vaccination of mice against H pylori induces a strong Th‐17 response and immunity that is neutrophil dependent. Gastroenterology 2009; 136:247–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akhiani AA, Schon K, Franzen LE, Pappo J, Lycke N. Helicobacter pylori‐specific antibodies impair the development of gastritis, facilitate bacterial colonization, and counteract resistance against infection. J Immunol 2004; 172:5024–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Becher D, Deutscher ME, Simpfendorfer KR, Wijburg OL, Pederson JS, Lew AM, et al Local recall responses in the stomach involving reduced regulation and expanded help mediate vaccine‐induced protection against Helicobacter pylori in mice. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40:2778–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raghavan S, Ostberg AK, Flach CF, Ekman A, Blomquist M, Czerkinsky C, et al Sublingual immunization protects against Helicobacter pylori infection and induces T and B cell responses in the stomach. Infect Immun 2010; 78:4251–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Czerkinsky C, Cuburu N, Kweon MN, Anjuere F, Holmgren J. Sublingual vaccination. Hum Vaccin 2011; 7:110–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cuburu N, Kweon MN, Song JH, Hervouet C, Luci C, Sun JB, et al Sublingual immunization induces broad‐based systemic and mucosal immune responses in mice. Vaccine 2007; 25:8598–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Song JH, Kim JI, Kwon HJ, Shim DH, Parajuli N, Cuburu N, et al CCR7‐CCL19/CCL21‐regulated dendritic cells are responsible for effectiveness of sublingual vaccination. J Immunol 2009; 182:6851–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kweon MN. Sublingual mucosa: a new vaccination route for systemic and mucosal immunity. Cytokine 2011; 54:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hervouet C, Luci C, Cuburu N, Cremel M, Bekri S, Vimeux L, et al Sublingual immunization with an HIV subunit vaccine induces antibodies and cytotoxic T cells in the mouse female genital tract. Vaccine 2010; 28:5582–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Milling S, Yrlid U, Cerovic V, MacPherson G. Subsets of migrating intestinal dendritic cells. Immunol Rev 2010; 234:259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lawson LB, Norton EB, Clements JD. Defending the mucosa: adjuvant and carrier formulations for mucosal immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2011; 23:414–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Norton EB, Lawson LB, Freytag LC, Clements JD. Characterization of a mutant Escherichia coli heat‐labile toxin, LT(R192G/L211A), as a safe and effective oral adjuvant. Clin Vaccine immunol 2011; 18:546–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lebens M, Terrinoni M, Karlsson SL, Larena M, Gustafsson‐Hedberg T, Kallgard S, et al Construction and preclinical evaluation of mmCT, a novel mutant cholera toxin adjuvant that can be efficiently produced in genetically manipulated Vibrio cholerae . Vaccine 2016; 34:2121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sjokvist Ottsjo L, Flach CF, Clements J, Holmgren J, Raghavan S. A double mutant heat‐labile toxin from Escherichia coli, LT(R192G/L211A), is an effective mucosal adjuvant for vaccination against Helicobacter pylori infection. Infect Immun 2013; 81:1532–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Summerton NA, Welch RW, Bondoc L, Yang HH, Pleune B, Ramachandran N, et al Toward the development of a stable, freeze‐dried formulation of Helicobacter pylori killed whole cell vaccine adjuvanted with a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat‐labile toxin. Vaccine 2010; 28:1404–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lundgren A, Bourgeois L, Carlin N, Clements J, Gustafsson B, Hartford M, et al Safety and immunogenicity of an improved oral inactivated multivalent enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) vaccine administered alone and together with dmLT adjuvant in a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled Phase I study. Vaccine 2014; 32:7077–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sjokvist Ottsjo L, Flach CF, Nilsson S, Malefyt Rde W, Walduck AK, Raghavan S. Defining the Roles of IFN‐γ and IL‐17A in Inflammation and Protection against Helicobacter pylori Infection. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0131444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flach CF, Svensson N, Blomquist M, Ekman A, Raghavan S, Holmgren J. A truncated form of HpaA is a promising antigen for use in a vaccine against Helicobacter pylori . Vaccine 2011; 29:1235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Norton EB, Lawson LB, Freytag LC, Clements JD. Characterization of a mutant Escherichia coli heat‐labile toxin, R192G/L211A, as a safe and effective oral adjuvant. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2011; 18:546–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mach N, Gillessen S, Wilson SB, Sheehan C, Mihm M, Dranoff G. Differences in dendritic cells stimulated in vivo by tumors engineered to secrete granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor or Flt3‐ligand. Cancer Res 2000; 60:3239–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lopez‐Dee Z, Pidcock K, Gutierrez LS. Thrombospondin‐1: multiple paths to inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2011; 2011:296069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shiu J, Blanchard TG. Dendritic cell function in the host response to Helicobacter pylori infection of the gastric mucosa. Pathog Dis 2013; 67:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mattsson J, Yrlid U, Stensson A, Schon K, Karlsson MC, Ravetch JV, et al Complement activation and complement receptors on follicular dendritic cells are critical for the function of a targeted adjuvant. J Immunol 2011; 187:3641–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lycke N, Bromander AK, Ekman L, Karlsson U, Holmgren J. Cellular basis of immunomodulation by cholera toxin in vitro with possible association to the adjuvant function in vivo . J Immunol 1989; 142:20–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lycke N, Tsuji T, Holmgren J. The adjuvant effect of Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli heat‐labile enterotoxins is linked to their ADP‐ribosyltransferase activity. Eur J Immunol 1992; 22:2277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shreedhar VK, Kelsall BL, Neutra MR. Cholera toxin induces migration of dendritic cells from the subepithelial dome region to T‐ and B‐cell areas of Peyer's patches. Infect Immun 2003; 71:504–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anosova NG, Chabot S, Shreedhar V, Borawski JA, Dickinson BL, Neutra MR. Cholera toxin, E. coli heat‐labile toxin, and non‐toxic derivatives induce dendritic cell migration into the follicle‐associated epithelium of Peyer's patches. Mucosal Immunol 2008; 1:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dubin PJ, Kolls JK. Th17 cytokines and mucosal immunity. Immunol Rev 2008; 226:160–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dixon BR, Radin JN, Piazuelo MB, Contreras DC, Algood HM. IL‐17a and IL‐22 induce expression of antimicrobials in gastrointestinal epithelial cells and may contribute to epithelial cell defense against Helicobacter pylori . PLoS One 2016; 11:e0148514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Total numbers of cytokine secreting cells are enhanced in the cervical lymph nodes after sublingual immunization.