Abstract

In the United States, primary stroke prevention in children with sickle cell anemia (SCA) is now the standard of care and includes annual transcranial Doppler ultrasound evaluation to detect elevated intracranial velocities; and for those at risk, monthly blood transfusion therapy for at least a year followed by the option of hydroxyurea therapy. This strategy has decreased stroke prevalence in children with SCA from approximately 11% to 1%. In Africa, where 80% of all children with SCA are born, no systematic approach exists for primary stroke prevention. The two main challenges for primary stroke prevention in children with SCA in Africa include: 1) identifying an alternative to blood transfusion therapy, because safe monthly blood transfusion therapy is not feasible; and 2) assembling a health care team to implement and expand this effort. We will emphasize early triumphs and challenges to decreasing the incidence of strokes in African children with SCA.

INTRODUCTION

“You cannot consider yourself an expert in sickle cell disease and not address the challenges in Nigeria.”

—Adetola Kassim, MBBS, Nigeria-born hematologist, Vanderbilt University, 2011

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is considered the first molecular genetic disease and has been recognized for centuries in West Africans, where SCD was referred to as “amosanin kashi” in the native Hausa lexicon. Since the recognition of SCD in modern medicine, there have been a series of landmark clinical trials to advance the care of children with SCD in high-income countries, transforming the disease from a life-threatening childhood condition, where the majority of children were not expected to live to adulthood, to a chronic disease of adulthood (1).

In high-income countries, before 1998, the most common permanent and devastating complication associated with SCD was stroke, which occurs in approximately 11% of children <19 years of age with sickle cell anemia (SCA), hemoglobin SS, in an unscreened and untreated population (2). The immediate and long-term consequences of strokes in children are devastating for both the child and the family. The social and educational consequences of stroke in childhood are compounded by the palliative and burdensome nature of secondary stroke prevention efforts, notably monthly blood transfusion therapy for an indefinite period. Monthly blood transfusions are challenging and unsustainable for many children and their families. Further, once a stroke has occurred and children receive monthly blood transfusion therapy, approximately 45% of the children with SCA and overt strokes are expected to have infarct recurrence over 5.5 years while receiving transfusions (3). Based on the devastating and progressive nature of overt strokes, even with standard therapy of monthly blood transfusion therapy, primary stroke prevention is the optimal strategy for children with SCA.

The Stroke Prevention Trial in Sickle Cell Disease (STOP) was completed in 1998 and provided the first evidence-based primary stroke preventive strategy in children with SCA (4). In this seminal randomized controlled trial, children with SCA between 2 and 16 years of age were screened for an elevated transcranial Doppler (TCD) measurement in the terminal portion of the internal carotid and the proximal portion of the middle cerebral artery. A higher velocity in any of these vessels is associated with decreased vessel diameter, and is used as a surrogate marker for intracranial vasculopathy. Among children with SCA and time averaged maximum TCD velocity of > 200 cm/sec, the rate of a stroke with only observation is approximately 10% to 13% per year (5). However, in the trial, monthly blood transfusion therapy (treatment arm) when compared to observation (standard arm) was associated with a 92% relative risk reduction of strokes (4). Further, when the findings of this trial were disseminated and implemented in a tertiary care medical center, approximately a log-fold decrease occurred in the rate of overt strokes, from 0.67 stroke events per 100 patient years to 0.06 stroke events per 100 patient years (6) in the pediatric population of children with SCA. Until recently, the major limitation for primary stroke prevention is that monthly blood transfusion therapy is quite burdensome and eventually requires daily chelation therapy to decrease the excessive iron stores which occurs secondary to the blood transfusion therapy (7).

Most recently, a phase III randomized controlled trial, TCD with Transfusions Changing to Hydroxyurea (TWiTCH) demonstrated that hydroxyurea therapy, a myelosuppressive, chemotherapeutic agent, is non-inferior to blood transfusion therapy for primary stroke prevention after an initial year of blood transfusion therapy in children with elevated TCD measurements (8). The results of these findings are likely to bolster not only the acceptance of primary prevention, but also improve adherence to a strategy based on hydroxyurea as primary stroke prevention, because regular blood transfusion therapy is not only burdensome for the patient and family, but also typically necessitates daily chelation therapy secondary to transfusion-related excessive iron stores (9).

NIGERIA ROAD TRIP IN 2011

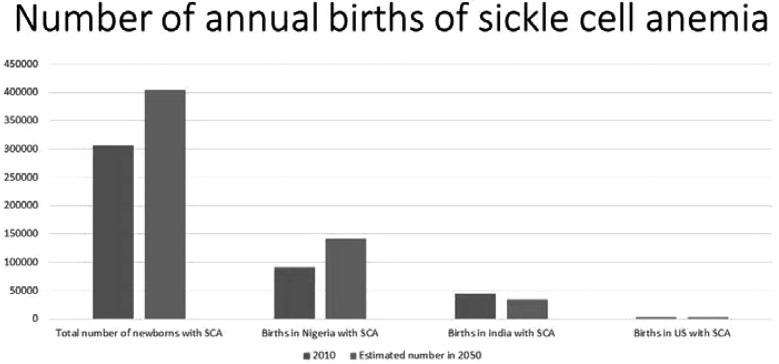

Nigeria has the highest birthrate of SCA, being home to at least 40% of the world’s children born with SCA annually (10) (Figure 1). This fact is not lost on Nigerian hematologists. In the summer of 2011, I (MRD) was invited by Nigerian hematology colleagues to take an academic road trip through northern Nigeria, one of the highest density areas of individuals with SCD in the world. The agreement was that we would volunteer to give 2 weeks of lectures in Nigeria. At the end of the trip, our accompanying spouses and teenage daughters would sponsor a weekend retreat for girls (ages 6−16 years) with SCA in Katsina, Nigeria, one of our selected destinations.

Fig. 1.

Estimated number of children born in the world (2010 and 2050, 305,773 and 404,190, respectively) with sickle cell anemia, Nigeria (91,011 and 140,837, respectively) and India (44,425 and 33,890, respectively), the two countries with the highest number of estimated births with sickle cell anemia, and the United States (2,842 and 3,379, respectively) (10).

After a series of academic lectures, our road-trip took us to Katsina, Nigeria, where the retreat was being held. In planning the retreat, we mistakenly omitted activities for the parents who had accompanied their daughters with SCD to Katsina for 2 days. The solution was that the three hematologists on the trip would spend their time with the parents for 8 hours while their daughters enjoyed the retreat. We subsequently created a 1-day, 8-hour interactive curriculum for the parents of children with SCA.

During the session with the parents, we were asked several questions regarding SCD-related stroke in children. One mother was concerned and puzzled as to why her daughter had difficulty keeping up with the academic challenges of her elementary school and subsequently stopped attending. In addition, she became unable to use her arm and began walking with a limp. We informed the parents that their young girl had a stroke and that children with SCD were at increased risk for strokes, which could recur if not treated. The parents then requested us to demonstrate the abnormal findings associated with a stroke. We later interviewed the mother and the girl together in front of approximately 60 parents. Immediately after the interview, five additional parents asked us to evaluate their daughters for strokes. We discovered that among the 42 girls attending the retreat, 16% (6 of 42) had previously unrecognized strokes.

MEDICAL IMPACT OF STROKE DIAGNOSES IN CHILDREN WITH SCD LIVING IN RESOURCE-CONSTRAINED SETTINGS

The diagnosis of a stroke in a child is a traumatic event for parents and their child. However, we had just made an unanticipated new diagnosis of strokes in six girls with SCA in Northern Nigeria, a setting where resources are limited, and a strategy for secondary stroke prevention is non-existent. The standard therapy in the United States for secondary stroke prevention is monthly blood transfusion therapy, with a goal of keeping the maximum hemoglobin S level less than 30% indefinitely (11). With blood transfusion therapy, the stroke recurrence rate is 1.9 events per 100 patient years; whereas, without any treatment the stroke recurrence rate is 29 events per 100 patient years (12,13). Thus, among the six girls attending the retreat with a stroke, we can expect that 50% will have a recurrence within 2 years of the primary event (12).

The non-government organization (NGO) that sponsored the weekend retreat provides medical care for more than 10,000 children with SCA. However, the NGO program had no hematologist, no effort to identify children with strokes, nor any TCD equipment to identify children at risk for future strokes. We estimate that in the catchment area of the Katsina NGO, at least 1,000 children with SCA had at least one stroke; with the majority of them having a second stroke as well. We estimated that instituting appropriate infrastructure and evidence-based strategies will decrease the prevalence of strokes by at least 50% in Nigerian children with SCA.

SOCIAL IMPACT OF A STROKE DIAGNOSIS IN CHILDREN LIVING IN RESOURCE-CONSTRAINED SETTINGS

For general populations living in low-income countries, very little data exist about acute and long-term management of strokes (14). A study in a low-income Asian setting found that less than 5% of the adults presenting to a stroke clinic were aware of their diagnosis (15).

The impact of strokes in children with SCD living in Nigeria is not well defined. In the region that we visited, there was no primary or secondary stroke prevention program for SCD. The initial child whom we evaluated was no longer in school because of the perception that she was unable to keep up with her academic tasks. Therefore, attending school was deemed unproductive, and socially awkward. The sequelae of strokes have not been specifically studied in Nigerian children; however, after a stroke in a child, motor and cognitive disabilities are common worldwide (16−18), particularly in low-resource countries where up to 70% of stroke victims have significant neurological deficits (19). In addition, strokes are the major cause of symptomatic seizures and epilepsy in children with SCA in Nigeria (20); these medical complications often go undetected and are under-treated.

A TARGETED STRATEGY TO PREVENT STROKES IN CHILDREN WITH SCA LIVING IN NIGERIA

Given our recent experience in Northern Nigeria, we felt obligated to address the glaring need for primary stroke prevention in children with SCA. Still, we were torn between providing resources to support a primary stroke program or identifying a testable hypothesis to support an initial feasibility trial, and ultimately a phase III randomized controlled clinical trial for primary stroke prevention in Nigeria. We also recognized that if we were to take the path of a clinical trial to identify the optimal stroke prevention strategy, we had to forgo working with the NGO and operate within the confines of a teaching hospital and the spectrum of academic providers (attending physicians and fellows). Working within the Nigerian medical system would compel us to work with its research team of health care providers and ancillary staff on how to conduct rigorous patient-oriented research. The NGO did not have an approach to prevent strokes in children with SCA and we could only imagine the same scenario playing out in dozens of Nigerian communities, and decided that the more scalable option was to work with physician led teams at academic centers.

After the summer Nigerian road trip of 2011 and with much deliberation, we elected to submit grant applications. We ultimately received four grants focused on primary stroke prevention in Nigeria and one grant focused on secondary stroke prevention in children with SCA in Nigeria. The first grant was a feasibility trial using hydroxyurea therapy in Kano, Nigeria, at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital. In this feasibility trial, we elected to use fixed low-dose hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg/d) for primary stroke prevention in children with SCA, as opposed to the alternative of instituting blood transfusion therapy for primary prevention of strokes in children with SCA and elevated TCD measurements (1R21NS080639). The second grant was from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to support training of the Nigerian clinical research team; and the third grant from the Aaron Ardoin Foundation to facilitate meetings between the Vanderbilt and Nigerian research teams and provide TCD training and TCD equipment for the Nigerian team. Most recently, our team received funding for a phase III randomized controlled clinical trial for primary stroke prevention at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital in Kano Nigeria (R01NS094041), referred to as the Stroke Prevention in Nigeria (SPRING) trial (NCT02560935). The trial will test the hypothesis that moderate-dose hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg/d) when compared to low-dose hydroxyurea therapy (10 mg/kg/d) is superior for primary stroke prevention in children with elevated TCD measurements. We were also funded by the Thrasher Foundation to conduct a secondary stroke prevention trial at the same Nigerian institution, whereby children with a pre-existing stroke will receive moderate- versus low-dose hydroxyurea therapy for at least 2 years (NCT02675790).

PROMISING EARLY RESULTS OF THE FEASIBILITY TRIAL

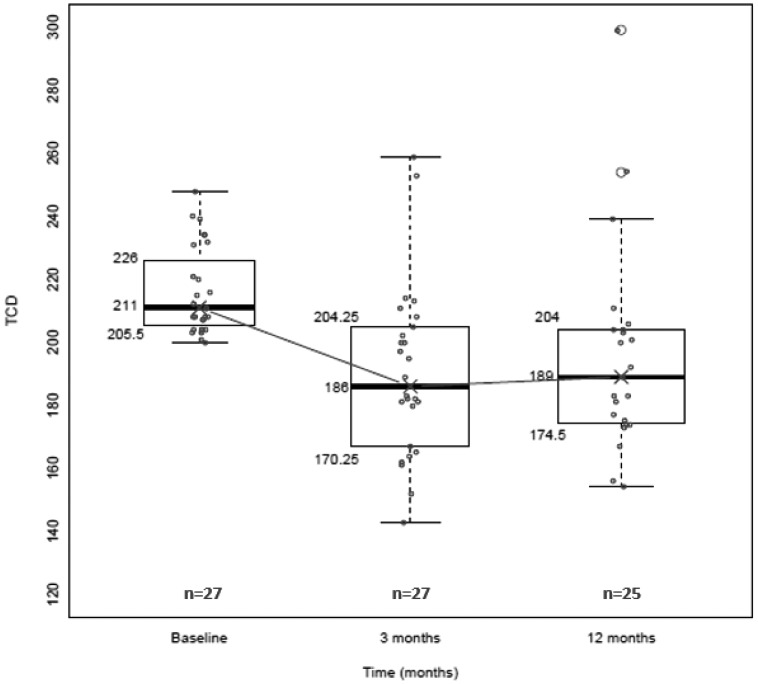

Data from completion of a feasibility trial in Kano, Nigeria, at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (NCT01801423) was quite encouraging. The early results demonstrated that hydroxyurea therapy is an option in sub-Saharan Africa, but requires extensive extramural support for capacity building (21). Equally important, we found preliminary evidence that an elevated TCD measurement could be reduced by promptly instituting hydroxyurea therapy, rather than chronic blood transfusions, which is standard care in the United States, but impractical to perform in sub-Saharan Africa. In the 25 study participants who were started on hydroxyurea therapy within weeks of detecting an elevated TCD measurement, 80% decreased to below the treatment threshold (< 200 cm/second in both vessels) after 3 months on hydroxyurea therapy (Figure 2). The decreases in TCD measurements with hydroxyurea therapy were comparable to results achieved with blood transfusion therapy, where approximately 50% of elevated TCD measurements decrease to normal levels after a mean duration of 4 months (22).

Fig. 2.

In the Nigerian feasibility trial for primary stroke prevention (NCT01801423), the transcranial Doppler (TCD) measurement changes at 3 months and 12 months in study participants with sickle cell anemia and elevated TCD measurements. All participants were started on a fixed moderate dose of hydroxyurea therapy (~20 mg/kg/d), 80% of the participants had their TCD values decrease to normal measurements (< 200 cm/second in both vessels) after 3 months on hydroxyurea therapy and maintained a normal TCD value after 12 months. The values represent the right middle cerebral artery if the right middle cerebral artery was greater than the left; otherwise we used the left middle cerebral artery.

We identified three lines of evidence which showed that hydroxyurea therapy was potentially an initial alternative to regular blood transfusion for primary stroke prevention in Africa. First, results in the feasibility trial demonstrated a significant decrease in TCD measurement after 3 months of fixed moderate-dose hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg/d) (Figure 2). Second, summary of the results from a pooled analysis of 7 prior before and after studies demonstrated that on average, hydroxyurea therapy reduced TCD measurements by approximately 25 cm/sec in children with SCA (11). Third, the early cessation of the TWiTCH trial (NCT01425307) demonstrated that hydroxyurea therapy following at least 1 year of blood transfusion therapy was non-inferior to continuous blood transfusion therapy in preventing strokes in children with SCA and elevated TCD measurements (8).

THE DUAL MISSION OF CONDUCTING PATIENT-ORIENTED RESEARCH AND PROVIDING A MEDICAL SERVICE

The SPRING trial is the only National Institutes of Health (NIH) − sponsored trial poised to determine what dose of hydroxyurea therapy will prevent strokes in a region of the world where most children with SCA are born. Further, the trial will determine the efficacy of starting hydroxyurea therapy immediately after the elevated TCD measurement is detected, as opposed to initiating blood transfusion therapy for at least 1 year, followed by hydroxyurea therapy at maximum tolerated dose, the current standard of care in the United States (8). A comparison between the SPRING and TWiTCH trials is described in Table 1. Our decision to choose a dose lower than the maximum tolerated dose of hydroxyurea therapy was based on our preliminary data demonstrating 20 mg/kg/d is sufficient to decrease TCD values, the biggest risk factor for strokes. The lower dose of hydroxyurea therapy, 10 mg/kg/d, may have benefit in preventing strokes because of its demonstrated value in preventing vaso-occlusive pain events and increasing hemoglobin levels in before and after studies in low- or middle-income countries (23−25). Importantly for resource limited countries, if 10 mg/kg/d of hydroxyurea therapy is as effective in preventing strokes as 20 mg/kg/d of hydroxyurea therapy and does not require the requisite laboratory monitoring, then twice as many children can be treated to prevent strokes for a lower cost because of the absence of laboratory surveillance.

TABLE 1.

Differences Between the TWiTCH Trial (NCT01425307) and SPRING Trial (NCT02560935) for Primary Prevention of Strokes in Children With Sickle Cell Anemia Living in High Income and Low Income Countries, Respectively

| Property | TWiTCH Trial | SPRING Trial |

|---|---|---|

| Design | RCT comparing standard transfusion vs. initial transfusion followed by hydroxyurea therapy | RCT of hydroxyurea therapy comparing moderate vs. low dose |

| Primary objective | Determine the non-inferiority of maximum tolerated dose of hydroxyurea therapy for primary prevention of strokes in children already receiving blood transfusion therapy | Determine whether moderate fixed dose of hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/k/g/d) is superior to low-dose hydroxyurea therapy (10 mg/kg/d) for primary stroke prevention |

| Age of participants (y) | 4 to 16 | 5 to 12 |

| Number of participants | 121 | 220 |

| Hydroxyurea dose | Escalated to maximum tolerated dose (typically 25 to 35 mg/kg/d) | Fixed dose of hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg/d vs. 10 mg/kg/d) |

| Study location | 26 centers in United States and Canada | 3 centers in Nigeria with estimated 10,000 eligible children with sickle cell anemia. |

| Length of time receiving study drug or standard therapy | Approximately 18 months (planned 24 months) | 36 months |

| Pretrial status | All participants were on initial standard care of regular blood transfusion for primary stroke prevention before randomization | All participants were treatment naïve for any primary stroke prevention therapy before randomization |

| Primary endpoint | Abnormal TCD measurement | Clinical stroke |

Abbreviations: TWiTCH, Transfusions Changing to Hydroxyurea trial; SPRING, Stroke Prevention in Nigeria trial; RCT, randomized control trial; TCD, transcranial Doppler ultrasound.

We deliberately structured the primary hypothesis of the trial such that, regardless of final results, the optimal dose of hydroxyurea therapy for primary stroke prevention in Nigeria will be determined. Either 20 mg/kg/d of hydroxyurea therapy will be superior to 10 mg/kg/d of hydroxyurea therapy, or the two doses will have equivalent efficacy for primary stroke prevention. In either case, the answer will provide an option for primary stroke prevention for the region of the world where SCA is most prevalent and no primary stroke prevention strategy exists.

EARLY FAILURES IN ATTEMPTS TO PREVENT STROKES IN CHILDREN WITH SCA IN NIGERIA

In our eagerness to move forward with our research agenda, we failed to acknowledge many of the institutional and systematic barriers for international research. Despite our experience in performing investigator-initiated NIH-funded clinical trials in the United States, we were unaware of some of the unique opportunities and challenges associated with undertaking a clinical trial in a low-resource setting. We assumed that travel to and from Nigeria would be routine for the study staff and physicians; however, several barriers occurred preventing travel, including problems with obtaining travel visas in a timely manner for members of the Nigerian research team. In addition, Boko Haram terrorist activity in Northern Nigeria generated significant Vanderbilt University leadership concerns about safety of travel to the study sites by research team members. Substantial team effort went into addressing these concerns, including securing high-level institutional support. Ultimately, the University policy permitted faculty to travel to Nigeria.

Routine communication, the most basic component of research, was also limited. We anticipated that investigators could communicate weekly via various modes of internet and routine telephone calls; however, we were wrong. Initially, only approximately 30% of the phone calls were successful, and the majority of calls were of poor quality and expensive. Our transatlantic weekly research meetings dramatically improved after we switched to voice-only internet communication, allowing for successful group meetings approximately 75% of the time.

Shipping large equipment was an unanticipated significant challenge. We received four donated de-commissioned imaging ultrasound machines from the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at Washington University School of Medicine, weighing approximately 400 pounds each, along with the purchase of the appropriate imaging probes to detect elevated TCD velocities. However, we were unaware of the extensive regulatory forms required to ship the donated imaging ultrasound machines to the receiving institutions. The entire process required dozens of hours and multiple international phone calls between academic institutions, regulatory agencies, and the shipping company. After 6 months of effort, we remain hopeful that delivery of the machines is imminent. In several cases, the requested requisite documentation and government processes to donate the imaging ultrasound machines were not previously established at the local institutions. In addition, the costs of shipping the large machines to the research sites, originally covered in the feasibility trial, exceeded the initial budget. Ultimately, philanthropic funds covered these shipping costs.

We dramatically underestimated the regulatory legal requirements for conducting a clinical trial outside of the United States. We were completely unaware that our clinical trial would require extensive institutional legal oversight at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital followed by outside legal consultation with experts in Nigerian medical contract law to ensure that the trial met all Nigeria regulatory requirements. Meeting the dual requirements of both sets of lawyers challenged our ability to initiate subcontracts in a timely fashion. Because of the delay in getting an activated subcontract, the research team in Northern Nigeria had to wait more than 6 months to be paid from the grant, causing a high level of financial hardship; and resulting in the principal investigator providing substantial out-of-pocket funds to meet the pre-determined training schedule required to start the trial on time.

Just as importantly, we did not predict that obtaining the study drug, hydroxyurea, would be challenging. Hydroxyurea is readily available in Nigeria for children and adults with SCD and certain cancers. Initially, Bristol Meyers Squibb agreed to donate hydroxyurea to Vanderbilt University School of Medicine for the NIH-funded feasibility trial; however, contract terms associated with this were not acceptable to the Vanderbilt legal leadership, and we were unable to accept the donated hydroxyurea. As a short-term solution, we were able to ship hydroxyurea from the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Research Pharmacy directly to the pharmacy at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital. However, for the phase III trial, we had to identify a pharmaceutical company that provides hydroxyurea therapy and was also approved by the Nigerian National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (Nigeria’s equivalent to the United States Federal Drug Administration).

Determining the quality of study drug is not routine practice for a clinical trial team. We simply assume that the study drug has the stated purity and potency. Yet ensuring an appropriate Nigerian source for hydroxyurea became the rate-limiting step for the trial to move forward. After 6 months of earnest effort, we identified a company in the United States that would determine the purity and potency of the hydroxyurea capsules available in Nigeria. We subsequently had the hydroxyurea capsules from two different pharmaceutical companies providing hydroxyurea in Nigeria tested for purity and potency. Fortunately, both hydroxyurea capsules from the two different companies met appropriate quality metrics, allowing our team to purchase the study drug in Nigeria. The added advantage of this strategy was that Nigerian hematologists obtaining hydroxyurea from these two companies were confident of drug purity. Moreover, we identified a local source of hydroxyurea for future therapies and research by Nigeria-based clinical teams. Table 2 identifies the unique opportunities and our solutions that we encountered when conducting the trials in Nigeria.

TABLE 2.

List of unanticipated opportunities that were identified in initiating the feasibility SPIN Trial and the phase III randomized controlled clinical trial for primary prevention of strokes in children with sickle cell anemia in Nigeria SPRING Trial

| 1. Opportunity: A pharmaceutical company donation of study drug, hydroxyurea, did not translate into our academic institution to accept the donated product. |

| Solution: Initially purchased the study drug, hydroxyurea therapy from our institutional pharmacy, but ultimately had to find a pharmaceutical company that had readily available hydroxyurea in Nigeria. We also had to ensure that the Nigeria National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (Nigeria equivalent to the United States Federal Drug Administration), approved the pharmaceutical company production of hydroxyurea therapy. |

| 2. Opportunity: Donating and shipping large equipment to the study site. In this case, the shipping of imaging transcranial Doppler machines that weigh more than 400 pounds. |

| Solution: To the extent possible, limit the dependence of starting the trial on the study site receiving large equipment. We elected to use non-imaging transcranial Doppler ultrasound technology with machines that can be shipped easily via a postal carrier. |

| 3. Opportunity: The dual level of legal oversight (both university counsel and outside counsel with expertise in the legal affairs of Nigeria) required initiating a trial in Nigeria. |

| Solution: To the best of our ability, anticipate potential legal and regulatory barriers for initiating the trial in Nigeria, such as seeking out approval from the Nigeria National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control and ensuring that we have all research regulatory forms updated and renewed well before the designated deadlines. |

| 4. Opportunity: Research team members travel from Nigeria to the United States, with limitations in obtaining a visa from Nigeria to the United States. |

| Solution: Apply for visas sufficiently in advance, up to 1 year before anticipated travel. Also, when hiring Nigeria-based research staff, the perceived ability to secure a visa for travel to the United States should be included in the screening process. |

| 5. Opportunity: Ability to ensure that the hydroxyurea capsules that are available in Nigeria are of sufficient quality to be used in a clinical trial. |

| Solution: Identify a United States company that can determine the quality of the study drug (hydroxyurea) in an ongoing, reliable fashion. |

LESSONS GOING FORWARD

Identifying a dual mission that includes a critical patient-oriented research question and fulfills a humanitarian need in a resource-limited country is a challenging, but accomplishable goal. The major lesson that we learned when identifying compelling opportunities for medical humanitarian aid is that physician-scientists in the United States have the capability to extend their skill sets to build research capacity in low-income settings while simultaneously preventing human suffering. We believe that if we had taken a strategy focused strictly on humanitarian effort to prevent strokes in children with SCA living in Northern Nigeria, we would have likely failed. The major risk of failure was the low probability of funding beyond the finite funding period. Selecting the strategy of providing primarily humanitarian support would have likely resulted in fewer resources to accomplish the objective. Specifically, since 2012, our research team has received more than $5,500,000 in either federal or foundation support, a sum that we would not have likely been able to match with strict appeals for humanitarian aid to prevent strokes in children with SCA. Further, despite our best intentions, we had no evidence that simply offering hydroxyurea therapy for primary stroke prevention outside of a clinical trial setting would be beneficial and not cause harm to the children with high rates of malnutrition, malaria infection, and poor rates of vaccinations. The research question to be answered will also be informative for children with SCD who live in the United States.

Most importantly, to address the paramount objective of sustainable efforts, the Nigerian-based research team has and will continue to acquire important experience and skills during the conduct of the SPRING trial. Based on the evidence that conducting clinical trials improve standard care (26), we trust that these newly acquired skills will go beyond the scope of the trial and will be translated into improving standard care for children with SCA not included in the trial. As a result of our efforts, since 2012, at least a dozen physicians and research staff members from Nigeria have attended an intensive 1-month training program at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine focused on building research capacity and conducting ethical research. The original site investigator for the feasibility trial (NAG), subsequently received a full scholarship (David Satcher Award) for a Master’s Degree in Public Health at Vanderbilt School of Medicine, completed in 2015, and is now a multi-principal investigator for the SPRING trial. Two other research team members, Nigerian hematologists (A. Galadanci, MBBS, and Halima Bello Manga, MBBS), were recipients of the American Society of Hematology Visiting Training Program Scholarship, allowing them to attend an intensive 8- to 12-week research and mentoring experience at Vanderbilt University Medical School. We strongly believe that carefully crafted hypothesis-driven patient-oriented research in low-resource settings can be leveraged to advance the field, to build capacity, and to prevent human suffering.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants 1R21NS080639 and R01NS094041 and by grants from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Burroughs Wellcome Foundation, and the Aaron Ardoin Foundation.

The authors thank the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis for their donation of imaging ultrasound machines and Cindy Terrill for manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

DISCUSSION

Mackowiak, Baltimore: You stated in your presentation that the rate of malaria infection in the hydroxyurea group of 25 children with sickle cell anemia was lower when compared to the observation group of 210 children without sickle cell anemia

DeBaun, Nashville: Correct, the data are preliminary. However, there is some theoretical evidence that hydroxyurea may decrease the rate of malaria infection, magnitude of parisitemia, or both.

Boxer, Ann Arbor: Michael, what is the impact, if any, of genetic counseling in these families with sickle cell disease?

DeBaun, Nashville: Genetic counseling is a complex process. One in four people in Nigeria has sickle cell trait, and in northern Nigeria, which is predominately Muslim, the prevalence is probably higher because there is a high rate of intermarriage within ethnic groups. To my knowledge, this is very limited pre-marital and pre-conception genetic counseling, particularly outside of the urban areas.

Forrest, New Haven: A great paper. My daughter who is a pediatrician and in Boston has recently published a paper showing a very high degree of proteinuria as either measured as urinary proteins or by more sensitive means. Is there a correlation between proteinuria and stroke in sickle cell?

DeBaun, Nashville: That is a very good question. To my knowledge, no longitudinal study has been conducted to determine whether proteinuria is a harbinger for cerebral infarcts or cerebral vasculopathy. One would think because of the vascular bed of the kidney, as well as the vascular bed in the brain are inter-related, such that when you identify vasculopathy in the kidneys you have the same pathology in the brain; however, the systematic evaluation of both vascular beds has not been done.

LeBlond, Billings: I just want to say that the first cell that sickles in the human with sickle cell disease is almost certainly not in the spleen but in the kidney because of the low pH, the low oxygen tension, and the high osmolality.

DeBaun, Nashville: Your point is well taken, and there have been studies using GFR measured via nuclear medicine scans showing infants as young as 24 months have hyper filtration indicating kidney disease.

Forrest, New Haven: As Frank Epstein pointed out, it’s the highest GFR and renal blood flow known to man in any disease.

LeBlond, Billings: I was intrigued by your observation that the two families eligible for the trial elected not to participate because of the parents thought this was too good to be true. I had a similar experience in Uganda in 1991−1992 trying to get informed consent from individuals who had no concept of informed consent. I wonder if you could elaborate a little more on how you approached informed consent in an environment where clinical research has not been customary. When we tried to get signed consent, they thought it was a contract and wondered what their obligation was. We had the only treatment for meningitis available. Potential participants were turning down the study because of the implied contractual relationship, signing the form.

DeBaun, Nashville: We spent an inordinate amount of time focused on team education about the trial, including the nurses, research associates, and research assistants. We requested that the research team spend the same amount of time with potential participating families. We developed a family-centered hydroxyurea handbook which was translated to Hausa, the native language. We set up a structure so that no single parent could sign informed consent without acknowledging the wishes of the second parent. To reinforce this concept, everyone got informed consent and hydroxyurea handbook brochure to take home and was encouraged to review these materials with household leadership. The individuals who returned with these materials were the ones that agreed to participate in the trial. We also spent a lot of time making sure that this was not a physician effort, but a community effort, and that the community leaders endorsed this research activity as important.

Anne Gershon, New York City: Very, very interesting and nice paper. In the US strokes in children are very rare but a major cause seems to be following varicella, and not the vaccine, but the disease which we’re of course seeing less and less of. I wonder whether you have had any experience with that in Nigeria.

DeBaun, Nashville: Up until recently in the United States, 11% of the children with sickle cell anemia developed strokes. Now approximately 1% of the children with sickle cell anemia in the United States developed strokes due to the almost uniform acceptance of transcranial Doppler screening and treatment with regular blood transfusion therapy for those with elevated measurements. For children with sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of stroke is at least 11%, with negligible contribution from a prior varicella infection. We believe that using a similar strategy embraced in the United States, but substituting hydroxyurea therapy for blood transfusion therapy, we can substantially decrease the prevalence of strokes.

Anne Gershon, New York City: More and more, the varicella vaccine is being used around the world and WHO has finally said it’s time for there to be more use of this vaccine so things are changing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chaturvedi S, DeBaun MR. Evolution of sickle cell disease from a life-threatening disease of children to a chronic disease of adults: the last 40 years. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:5–14. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powars D, Wilson B, Imbus C, Pegalow C, Allen J. The natural history of stroke in sickle cell disease. Am J Med. 1978;65:461–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90772-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hulbert ML, McKinstry RC, Lacey JL, et al. Silent cerebral infarcts occur despite regular blood transfusion therapy after first strokes in children with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2011;117:772–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams RJ, McKie VC, Hsu L, et al. Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:5–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807023390102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams RJ. Big strokes in small persons. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1567–74. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.11.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enninful-Eghan H, Moore RH, Ichord R, Smith-Whitley K, Kwiatkowski JL. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and prophylactic transfusion program is effective in preventing overt stroke in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 2010;157:479–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood JC, Cohen AR, Pressel SL, et al. Organ iron accumulation in chronically transfused children with sickle cell anaemia: baseline results from the TWiTCH trial. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:122–30. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware RE, Davis BR, Schultz WH, et al. Hydroxycarbamide versus chronic transfusion for maintenance of transcranial doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell anaemia-TCD With Transfusions Changing to Hydroxyurea (TWiTCH): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387:661–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang WC, Dwan K. Blood transfusion for preventing primary and secondary stroke in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD003146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003146.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piel FB, Hay SI, Gupta S, Weatherall DJ, Williams TN. Global burden of sickle cell anaemia in children under five, 2010-2050: modelling based on demographics, excess mortality, and interventions. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeBaun MR, Kirkham FJ. Central nervous system complications and management in sickle cell disease: a review. Blood. 2016;127:829–38. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-618579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassim AA, Galadanci NA, Pruthi S, DeBaun MR. How I treat and manage strokes in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2015;125:3401–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-551564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagunju IA, Brown BJ, Sodeinde OO. Stroke recurrence in Nigerian children with sickle cell disease treated with hydroxyurea. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2013;20:181–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brainin M, Teuschl Y, Kalra L. Acute treatment and long-term management of stroke in developing countries. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:553–61. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra NK, Patel H, Hastak SM. Comprehensive stroke care: an overview. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganesan V, Hogan A, Shack N, Gordon A, Isaacs E, Kirkham FJ. Outcome after ischaemic stroke in childhood. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:455–61. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westmacott R, Askalan R, MacGregor D, Anderson P, Deveber G. Cognitive outcome following unilateral arterial ischaemic stroke in childhood: effects of age at stroke and lesion location. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:386–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cnossen MH, Aarsen FK, Akker S, et al. Paediatric arterial ischaemic stroke: functional outcome and risk factors. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:394–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolk A, Ennok M, Laugesaar R, Kaldoja ML, Talvik T. Long-term cognitive outcomes after pediatric stroke. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagunju IA, Brown BJ. Adverse neurological outcomes in Nigerian children with sickle cell disease. Int J Hematol. 2012;96:710–8. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galadanci NA, Abdullahi SU, Tabari MA, et al. Primary stroke prevention in Nigerian children with sickle cell disease (SPIN): challenges of conducting a feasibility trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:395–401. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwiatkowski JL, Yim E, Miller S, Adams RJ, et al. Effect of transfusion therapy on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography velocities in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:777–82. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel DK, Mashon RS, Patel S, Das BS, Purohit P, Bishwal SC. Low dose hydroxyurea is effective in reducing the incidence of painful crisis and frequency of blood transfusion in sickle cell anemia patients from eastern India. Hemoglobin. 2012;36:409–20. doi: 10.3109/03630269.2012.709897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel S, Purohit P, Mashon RS, et al. The effect of hydroxyurea on compound heterozygotes for sickle cell-hemoglobin D-Punjab — a single centre experience in eastern India. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1341–6. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svarch E, Machin S, Nieves RM, Mancia de Reyes AG, Navarrete M, Rodriguez H. Hydroxyurea treatment in children with sickle cell anemia in Central America and the Caribbean countries. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:111–2. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West J, Wright J, Tuffnell D, Jankowicz D, West R. Do clinical trials improve quality of care? A comparison of clinical processes and outcomes in patients in a clinical trial and similar patients outside a trial where both groups are managed according to a strict protocol. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:175–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]