Abstract

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) is one of several human cell mechanisms utilized to repair mutable mistakes within DNA, particularly after DNA is replicated. MMR function is dependent upon heterodimerization of specific MMR proteins that can recognize base-base mispairs as well as frameshifts at microsatellite sequences, followed by the triggering of other complementary proteins that execute excision and repair or initiate cell demise if repair is futile. MMR function is compromised in specific disease states, all of which can be biochemically recognized by faulty repair of microsatellite sequences, causing microsatellite instability. Germline mutation of an MMR gene causes Lynch syndrome, the most common inherited form of colorectal cancer (CRC), and biallelic germline mutations cause the rare constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome. Somatic inactivation of MMR through epigenetic mechanisms is observed in 15% of sporadic CRC, and a smaller portion of CRCs possess biallelic somatic mutations. A novel inflammation-driven nuclear-to-cytoplasmic shift of the specific MMR protein hMSH3 is seen in up to 60% of sporadic CRCs that associates with metastasis and poor patient prognosis, unlike improved outcome when MMR is genetically inactivated. The mechanism for MMR inactication as well as the component affected dictates the clinical spectrum and clinical response for patients.

INTRODUCTION: DNA REPAIR MECHANISMS

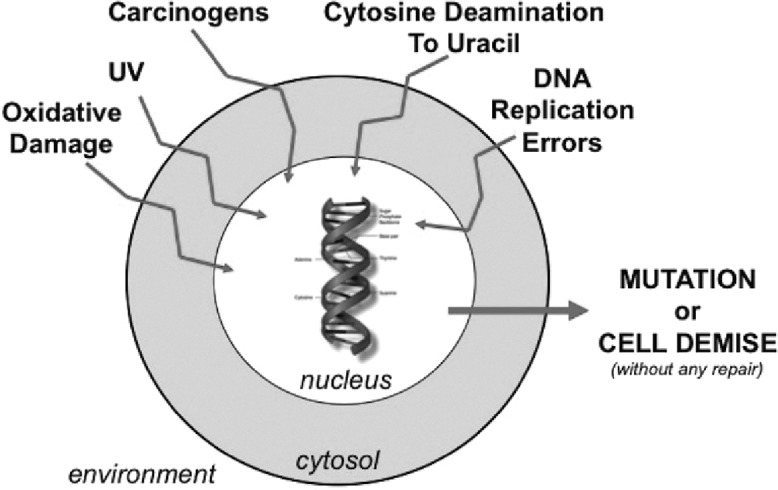

Human cells are constantly bombarded by a variety of insults that damage DNA. Extrinsic causes that damage DNA include ultraviolet radiation, carcinogens, and oxidative stress to the cell, among others. DNA damage can also occur by intrinsic mechanisms. For instance, cytosine can spontaneously deaminate to uracil within the DNA strand, altering the genetic code. Additionally, the replication of DNA in the S phase of the cell cycle is dependent upon the absolute accuracy of copying template DNA into newly synthesized strands for daughter cells. This process requires polymerases with high fidelity editing functions, but replication errors can still occur despite these functions (Figure 1). Both extrinsic and intrinsic causes for DNA damage can block DNA replication and DNA transcription processes, impair gene expression, and cause genomic instability and mutagenesis leading to human disease. In particular, DNA damage to stem cells that differentiate and are the precursors to multiple cell lineages are particularly troublesome and contribute to cancer generation. In the absence of any repair, cells will accumulate mutations in their DNA (transmitting damage to progeny cells) or cells undergo demise (halting the DNA damage transmission) (Figure 1). Evolutionarily, mutagenesis may be important for single cell organisms to adapt to hositle environments to self-select cells capable of surviving the changed environment.

Fig. 1.

Some mechanisms for DNA damage in a human cell. Extrinsic environmental exposures as well as naturally occuring deamination and/or DNA replication error events damage DNA constantly, which if not repaired allows accumulation of mutations in progeny cells or eventually triggers cell demise.

Fortunately, human cells have evolved mechanisms to repair damaged DNA, preventing transmission of mutations to progeny cells. DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair corrects and prevents errors when the DNA double strand is damaged. Homologous recombination repairs DSBs in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, and involves replication protein A as a substrate for ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related at single-strand overhangs, with subsequent replication protein A replacement by RAD51 that is recruited to ssDNA utilizing BRCA1/BRCA2/PALB2 proteins in a process that is dependent on the DNA MMR protein hMSH3 (1,2). Non-homologous end joining repair repairs DSBs in the early phases of the cell cycle where KU70 and KU80 (encoded by XRCC6 and XRCC5 genes, respectively) bind the free ends of the interrupted DNA double strand, and recruit DNA PKcs (encoded by protein kinase DNA-activated catalytic polypeptide or PRKDC) that directs XRCC4 and LIG4 to mediate end joining (1). There are at least three systems that direct repair of DNA separate from DSB repair (3,4). Base excision repair contains a series of proteins (glycosylases) that removes chemical modifications of DNA (e.g., cytosine deamination to uracil). Nucleotide excision repair functions to repair helix distortions (e.g., ultraviolet radiation damage) via exonucleases. DNA mismatch repair (MMR) corrects post-synthetic base mispairs. Thomas Lindahl of the Francis Crick Institute (for base excision repair), Aziz Sancar of the University of North Carolina (for nucleotide excision repair), and Paul Modrich of Duke University (for MMR) were recognized with the 2015 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their discoveries outlining DNA repair using model systems (5).

HUMAN DNA MMR

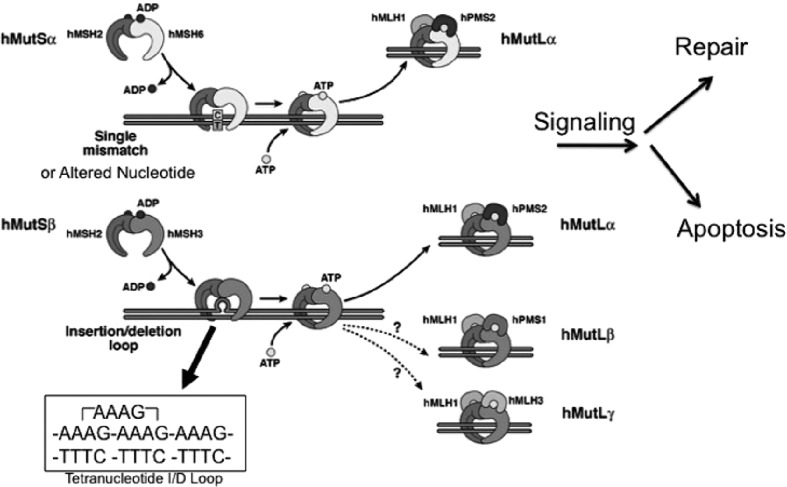

Human DNA MMR is an evolutionarily conserved cellular process that repairs mistakes which remain after DNA polymerases replicate DNA (2−4). MMR consists of two recognition complexes, hMutSα and hMutSβ, that are formed by heterodimeration of two MMR proteins (hMSH2–hMSH6 and hMSH2–hMSH3, respectively), and a signaling/execution complex, hMutLα, that is formed by heterodimerization of the MMR proteins hMLH1 and hPMS2 (Figure 2). The recognition profile for the hMutS recognition complexes are different in MMR, with functional overlap between the two complexes solely at insertion/deletion (I/D) loops of 2 nucleotides (2). hMutSα recognizes single base mispairs (e.g., G/T, A/C, etc.) and altered nucleotides (e.g., O6-methyguanine, 5-fluorodeoxyuracil, etc.) that are not complementary bases for the opposing DNA strand, and which if not repaired will introduce a point mutation in progeny cell DNA (2, 6−9). hMutSα also recognizes I/D loops of up to 2 nucleotides (2). I/D loops are formed when DNA microsatellites, repetitive sequences of up to 6 nucleotides (e.g., A, CA, CAG, AAAG, etc.) that are generally repeated 6 or more times (e.g., A10, CA25, CAG12, AAAG18, etc.) are not perfectly aligned between the two DNA strands [2]. Most of the ~100,000 microsatellites in the human genome are in non-coding regions of DNA, but some mono-, di-, and tri-nucleotide sequences are in exons that ultimately code for protein, and when frameshifted produces a truncated protein due to a newly introduced stop codon (2−4,10−13). Since the recognition profile of hMutSα is for I/D loops of 2 or less, hMutSα targets mono- and di-nucleotide frameshift slippages for repair (e.g., A10 paired with T9 produces an I/D loop of 1 nucleotide, and CA25 paired with GT24 produces an I/D loop of 2 nucloetides). Without hMutSα function or any subsequent MMR action, frameshift mutation occurs within the microsatellites (termed microsatellite instability, or MSI), which can easily be determined biochemically from within a tumor. Mutability of microsatellite sequences are dependent on the repeat length (a repeat of 25 units is more susceptible to frameshifts than a repeat of 12 units) and the 5’ and 3’ flanking nucleotides surrounding the microsatellite (11−13). hMutSβ’s recognition profile differs from hMutSα. hMutSβ recognizes I/D loops of 2 nucleotides or greater, and does not recognize I/D loops of 1 or single base mispairs (2,4,14,15). Thus, hMutSβ targets di-, tri-, and tetra-nucleotide frameshift slippages for repair as these microsatellites would have I/D loops of 2, 3, or 4, respectively (Figure 2). Once hMutSα and/or hMutSβ recognizes the DNA lesion, it stalls the cell’s progression towards mitosis, attracts hMutLα to bind, which then triggers other proteins (e.g., exonuclease and polymerase function) to complete repair of the lesion, or trigger cell demise (Figure 2) (2,3,7). In essence, MMR maintains the fidelity of DNA as it is replicated and transmitted to daughter cells.

Fig. 2.

Human DNA mismatch repair function. The hMutSα complex is made up of hMSH2 and hMSH6, and recognizes single base mispairs and insertion/deletion (I/D) loops of 2 microsatellite nucleotides or less. The hMutSβ comlex consists of hMSH2 and hMSH3, and recognizes I/D loops of 2 microsatellite nucleotides or more. An example of a tetranucleotide microsatellite I/D loop is depicted, demonstrating how the loop consists of 4 nucleotides. After recognition of the DNA defect by hMutSα or hMutSβ, the hMutLα complex comprising hMLH1 and hPMS2 binds either hMutS complex to signal the cell to repair DNA or trigger cell demise. There are other hMutL complexes, but their role on post-synthetic DNA repair has not been demonstrated. Based on: Grady et al (3).

Each of the three main MMR complexes (hMutSα, hMutSβ, and hMutLα) are heterodimers, and when bound as a heterodimer, each component protein is much more stable within the cell’s nucleus. When one of the component proteins are absent, the pairing heterodimer protein becomes unstable (2,16). For instance, loss of hMLH1, a component of hMutLα, will cause hPMS2 to become unstable and not detectable in the cell (16). This can be observed with immunohistochemistry of MSI colorectal cancers (CRCs) to help determine which MMR protein is absent, and if there might be a germline mutation (via any of the MMR genes) versus sporadic MSI CRC, which is invariably caused by hypermethylation of the promoter of only one MMR protein, hMLH1 (3,4,17−19).

Loss of any component of MMR will cause frameshift mutation at DNA microsatellites and is biochemically detected as MSI (2−4). However, the profile of MSI will differ based on the MMR defect. For instance, loss of hMSH6 would only affect hMutSα, and one would observe mostly mononucleotide MSI and some dinucleotide MSI. Loss of hMSH3 would only affect hMutSβ, and one would observe only di-, tri-, or tetra-nucleotide MSI, but no mononucleotide instability. Loss of hMSH2, hMLH1, or hPMS2 would produce pan-MSI for all markers as loss of these proteins affect both hMutS recognition complexes or hMutLα, the main signaling/execution MMR complex (2). A National Cancer Institute expert panel defined a collection of mono- and di-nucleotide markers to identify classic MSI-high (MSI-H) to determine which CRCs have lost MMR function (20). Since that panel reported, we now recognize other forms of MSI, including MSI-low (usually one marker of dinucleotide MSI only), and elevated microsatellite alterations at selected tetranucleotide repeats (EMAST) that are now associated with isolated hMutSβ (hMSH3) dysfunction. It has become apparent that MSI-low is the same as EMAST as both are caused by isolated hMutSβ dysfunction (2). The MSI and EMAST biomarkers are helpful in defining the cause for genomic instability in the tumor, the presence of hundreds of mutations in the CRC genome due to the MMR defect, and determining patient outcome and potential treatment responses as a result of the MMR defect.

For MSI-high CRCs, coding microsatellites are affected which drive the neoplastic process. Genes such as ACVR2, TGFBR2, and even hMSH3 and hMSH6 contain coding mononucleotide microsatellites and are commonly frameshift mutated in these CRCs (10,11,21−24). For EMAST CRCs, the importance of frameshift mutation is not clear, as fewer genes contain di-, tri-, and tera-nucleotide coding sequences (2).

The MMR proteins are tumor suppressors; that is, when present they contribute to appropriate and proctored repair of DNA to minimalize mutation capability and regulate cell growth through signaling when repair is needed. When absent, there is no or impartial MMR function depending on the defect, and mutations are passed to progeny cells that can allow for accelerated growth and neoplastic change.

COMMON CLINICAL FEATURES OF COLON CANCERS WITH DEFECTIVE DNA MMR

In CRCs that manifest complete loss of MMR function, several common features have been reported. CRCs displays MSI, and loss of MMR protein expression from the tumor is observed simultaneously and can be a surrogate for MSI detection (~92% correlation) (4,20). MSI CRCs are more often poorly differentiated on histology, and approximately 40% of MSI CRCs contain mucin, much higher compared to microsatellite stable (MSS) CRCs. MSI CRCs are hypermutated, containing 100−1000 mutations in the cancer genome, compared to a few dozen mutations with MSS CRCs (4,21). MSI CRCs contain diploid genomes unlike MSS CRCs which are generally aneuploid. Once MMR function is defective, frameshift mutations in coding microsatellites of ACVR2, TGFBR2, hMSH3, hMSH6, and others drive the pathogenesis from benign adenomas to malignancy in fairly rapid fashion (within months to 1−2 years as compared to decades for MSS CRCs) (4). In addition to taking out the function of these proteins via frameshift mutation of their genes, novel truncated peptides are generated which are immunogenic (4,25), attracting T cells into the epithelium as well as creating subepithelial lymphoid aggregates. It is believed that this immune reaction greatly improves patient survival over patients with MSS CRCs. Additionally, the immune reaction and control of cancer spread for patients with MSI CRCs can even be more robust with the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti−programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) therapy (4,26). However, patients with advanced stage MSI CRCs do not improve survival with 5-fluorouracil(5-FU)−based chemotherapy, as loss of MMR function precludes recognition of any 5-FU incorporated into DNA (7−9,27,28). MSI CRCs have a higher propensity for the right side of the colon, with >70% of tumors proximal to the splenic flexure (3,4,29−31).

DEFECTIVE DNA MMR CONDITIONS

There are now at least five known human conditions which are caused or influenced by defective MMR. Two are inherited via germline mutations, and three occur sporadically, with the type of somatic hit predicting the potential outcome of CRC patients.

Inherited Defective DNA MMR Conditions

Lynch syndrome is the most common inherited CRC syndrome, identified in ~3% of all CRC patients in CRC population-based studies (32), and patients have a lifetime risk of 80% for CRC (32−34). Patients can develop synchronous and metachronous cancers at young ages including CRC but also endometrial and ovarian cancer, other gastrointestinal cancers (stomach and small intestine, pancreas, biliary tract), urinary tract cancers, glioblastomas, and skin cancers (34) (Table 1). The DNA MMR defect in Lynch syndrome cancers is triggered by the autosomal dominant inheritance of a germline mutation of one of the DNA MMR genes (hMSH2, hMLH1, hMSH6, hPMS2, EPCAM), followed by somatic inactivation of its second allele (3,22,23,32−34). More than 85% of germline mutations are found in either hMSH2 or hMLH1 (32−34). Deletion of EPCAM, upstream of hMSH2 on chromosome 2, causes allele specific methylation hMSH2’s promoter and is a relatively rare cause for loss of hMSH2 expression and Lynch syndrome (33,34). There are some genotype-phenotype correlations — for instance, patients with hMSH6 or hPMS2 germline mutations present at a later age of onset for cancers (50s and 60s for age) compared to hMLH1 and hMSH2 germline patients (40s for age) (33,34). Universal screening for Lynch syndrome among all CRC patients have been proposed, and is implemented utilizing immunohistochemistry in several large academic medical centers (32). Patients and related family members should undergo genetic counseling for 1) possible germline genetic testing and its implications, and 2) with expert physician input, receive personal recommendations for surveillance of potential predicted natural occuring cancers as a result of having Lynch syndrome. Lynch CRCs can be differentiated from sporadic MSI CRCs on the basis of the absence of somatic BRAF mutations and absence of methylation of hMLH1 (Table 1) (33,34).

TABLE 1.

Inherited Forms of DNA Mismatch Repair Defects (Germline Mutations)

| Condition | MMR Genes Involved | Mechanism of MMR Inactivation | Clinical Frequency | Clinical Findings | Clinical Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lynch syndrome | hMSH2, hMLH1, hMSH6, hPMS2, EPCAM (NOT hMSH3) | Germline mutation, followed by somatic mutation of 2nd allele within tissue | Common: 3% of all CRCs | ~40 years of age CRC and GI tract cancer, female reproductive tract cancers, urinary tract cancers, skin, glioblastomas | Family history Germline testing after genetic counseling Careful surveillance for early tumor formation Lack BRAF mutations |

| CMMRD | Principally hMSH6 and hPMS2, but can also involve hMLH1, hMSH2 | Two (biallelic) MMR germline mutations | Extremely rare | <10 years of age CRC and GI tract cancer, hematological cancers, café-au-lait spots | Normal colon tissue may demonstrate MSI-H |

Abbreviations: MMR, mismatch repair; CRC, colorectal cancer; GI, gastrointestinal; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high; CMMRD, constitutional mismatch repair deficiency.

Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) is a very rare condition in which biallelic germline mutations in DNA MMR genes predispose to development of multiple cancers, often at very early ages. CMMRD individuals inherit a mutant MMR gene from each parent, commonly hMSH6 or hPMS2, due to these genes association with later onset patient presentation and the unlikelihood of prior age diagnosis, although any DNA MMR gene could be involved (34). Affected patients generally present in childhood, with brain tumors, colorectal and/or other gastrointestinal cancers (including some cases of multiple colonic adenomas), and with hematological malignancies such as leukemias and lymphomas commonly reported (34). Additionally, essentially all CMMRD patients exhibit café-au-lait spots (34). This unique, biallelic DNA MMR defect not only allows CRCs to exhibit MSI, but also normal colonic mucosa may demonstrate MSI and loss of MMR protein expression (Table 1) (34).

Somatic Defective DNA MMR Conditions

Sporadic MSI CRCs MMR defect is almost uniformly caused by inactivation of hMLH1 through hypermethylation of its promoter, preventing hMLH1 transcription (3,4,17−19,21,33,34). Sporadic CRCs exhibit loss of hMLH1 and hPMS2 at immunohistochemistry, and to differentiate this condition from a Lynch CRC from an hMLH1 germline patient or a Lynch-like CRC (see below), the presence of BRAFV600E and/or methylation of hMLH1 identifies the tumor as a sporadic MSI CRC (4,33,34). Sporadic MSI CRCs comprise 15% of all CRCs, more commonly develop at older ages (>70 years of age) and are more often found in famale patients (Table 2) (4,29,33,34).

TABLE 2.

Sporadic Forms of DNA Mismatch Repair Defects (Somatic Inactivation)

| Condition | MMR Genes Involved | Mechanism of MMR Inactivation | Clinical Frequency | Clinical Findings | Clinical Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sporadic MSI-H CRC | hMLH1 | Biallelic somatic methylation of the hMLH1 promoter | Common: 15% of all CRCs | Older age (>70 years More common in females | ~25% have somatic BRAF mutation |

| Lynch-like syndrome | hMSH2, hMLH1, hMSH6, hPMS2 | Biallelic MMR somatic mutations | ~1% (~2/3 of all DNA MMR germline negative patients) | Patients present younger than sporadic (54 years) | At present, clinical surveillance guidelines similar to Lynch |

| EMAST (elevated microsatellite alterations at selected tetranucleotide repeats | hMSH3 (isolated loss of function) | IL-6−induced, reversible, nuclear-to-cytosolic shift of hMSH3 | Up to 60% of all CRCs | Associated with advanced staged disease and metastasis Poor survival Higher frequency in African Americans | EMAST is caused by inflammation Patients respond to 5-FU Metastasis modulator to all CRCs |

Abbreviations: MMR, mismatch repair; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high; CRC, colorectal cancer; EMAST, elevated microsatellite alterations as selected tetranucleotide repeats; IL-6, interleukin 6; 5-FU, f-fluorouracil.

Lynch-like syndrome is so named because patients present with cancer at younger ages similar to Lynch syndrome, while manifesting MSI CRCs with associated loss of MMR protein expression; however, genetic testing fails to identify a germline MMR gene mutation. The MMR defect in Lynch-like CRCs, unlike germline mutation in Lynch patients, is two somatic hits within the CRC (33−36). As opposed to sporadic MSI-H CRCs, Lynch-like CRCs do not show epigenetic inactivation of hMLH1 or mutation in BRAF (34,36). The younger age of presentation fuels speculation that undiagnosed germline mutations may be implicated in at least some of these cases, but it appears clear that the cause of MSI within these CRCs are two somatic genetic events involving MMR genes. As many as 70% of clinically suspected Lynch syndrome patients with CRC and no germline mutation may be Lynch-like patients with CRC. Lynch-like patients demonstrate lower risk for CRC and extracolonic cancers in the Lynch spectrum, and patients may represent a spectrum in heterogeneity for cancer risk (Table 2) (33,34).

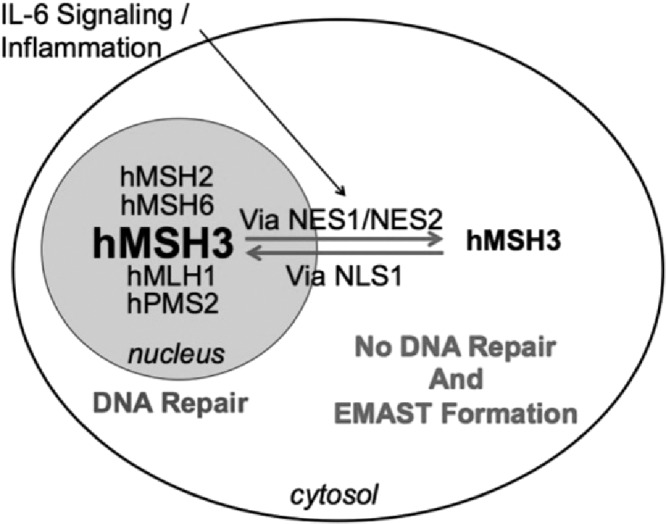

EMAST CRCs show evidence for isolated MMR complex hMutSβ (hMSH3) inactivity (demonstrated biochemically by tetranucleotide microsatellite frameshifts in markers, but also possessing dinucleotide or greater frameshifts), and this lack of hMutSβ activity reveals a differing clinical behavior for patients and EMAST CRCs than that described for typical MSI CRCs (which have complete loss of MMR function) (2,14,29,30). EMAST is the most common MMR defect among CRCs, appearing in 50% to 60% of all CRCs (2). EMAST CRCs show a strong association with infiltrating T lymphocytes and inflammation, but do not exhibit subepithelial lymph aggregates like MSI CRCs (14). They are more commonly found in patients with advanced stage CRCs, and associate with metastatic behavior and poor survival, unlike the “protective” and less metastatic behavior of typical MSI CRCs, and EMAST CRCs are nearly twice the frequency in African American compared to Caucasian patients likely contributing to disparity in survival (Table 2) (14,29). Because EMAST CRCs retain hMutSα function, 5-FU can be recognized by this MMR complex, and patients with EMAST CRCs respond to 5-FU (37). This is opposed to patients with typical MSI CRCs, who showcase a muted response to 5-FU (27,28). The mechanism for hMutSβ inactivity is unique, and does not involve mutation or epimutation. Evidence indicates that inflammation surrounding the epithelial cells, and in particular the pro-inflmmatory cytokine interleukin 6 (IL-6), triggers a reversible nuclear-to-cytosolic shift of hMSH3 (but not other MMR proteins), removing its activity from the nucleus where it normally participates in DNA MMR (2,38,39) (Figure 3). The shuttling of hMSH3 allows accumulation of nuclear DNA frameshift mutations and other DNA damage while in the cytosol (39). This mechanism matches the histological observation that EMAST CRCs show diminished heterogeneity for hMSH3 expression in CRC epithelial nuclei (2,15). hMSH3 is not involved in oncogenic transformation (40); however, it appears that the acquired somatic loss of hMutSβ function can modulate the behavior of already formed CRCs towards metastatic behavior (2,14,41).

Fig. 3.

Schematic for elevated microsatellite alterations at selected tetranucleotide repeats (EMAST) generation in a human cell. Inflammation, principally driven by interleukin 6 (IL-6), triggers a nuclear-to-cytosolic shift for the DNA mismatch repair protein hMSH3 via an sIL-6R/STAT3 mechanism. hMSH3 is uniquely shifted compared to other DNA MMR proteins. When hMSH3 is not in the nucleus, frameshift mutations can accumulate in the nucleus due to lack of hMutSβ function. Unpublished data indicate that hMSH3 shuttles between the nucleus and cytosol in response to IL-6 via specific nuclear localization signals (NLS) and nuclear export signals (NES). Based on: Tseng-Rogenski et al (39).

SUMMARY

There are several mechanisms to inactivate DNA MMR function, each associated with a specific clinical cancer condition, and all of which can be biochemically recognized by faulty repair of microsatellite sequences, causing MSI. MMR can be inactivated by germline (Lynch and CMMRD) or somatic (Lynch-like) mutation. It can be epigenetically inactivated via hypermethylation of hMLH1 (sporadic MSI CRCs). MMR function is partially affected through a novel nuclear-to-cytosol shuttling of hMSH3, inactivating hMutSβ (EMAST CRCs). Possessing a defective MMR CRC that is genetically or epigenetically inactivated generates novel peptides from expressed frameshifted genes, and immunologically portends improved prognosis for patients. On the other hand, inflammation-driven nuclear-to-cytosol shift for hMSH3 associates with increased probability for metastasis, worsening prognosis for patients. The mechanism for MMR inactivation as well as the component affected dictates the clinical spectrum and clinical response for patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the United States Public Health Service (R01 DK067287, U01 CA162147) and the A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute of the University of Michigan.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

DISCUSSION

Crofford, Nashville: Enjoyed your talk, it was wonderful. You mentioned the fact that in common variant Lynch syndrome where you have hypermethylation of MLH1, for example, that you can have mutations in coding protein genes for example, Type 2 TGF-beta receptor, that will be mutated in 90% of those cancers. In the case of EMAST, is there any evidence so far that there are mutations that, in coding for non-synonymous mutations?

Carethers, Ann Arbor: The answer is yes and no…. so I will tell you it’s not published. I will tell you some work that we are working on. So first of all, EMAST tends to effect di-nucleotide, tri-nucleotide, and tetra-nucleotide sequences, causing insertion/deletion loops of 2, 3, or 4 nucleotides. So the number of genes with 2, 3, or 4 nucleotide repeats compared to those that have mononuclotide sequences like TGF-beta or ACVR2 go down; in fact, there is probably no gene with a tetranucleotide sequence. There are genes with trinucleotide repeats with some have been shown to become mutated, but whether it is functional or not, that’s another question. We have looked at in our lab the difference between primary colorectal cancers with their matching, metastatic lesions in the liver. We have about 100 or so cases that we have not published yet. We have examined 141 different loci. We did not find any difference between the primary and the metastatic lesion for this type of defect. There were shifts but it was not real different between the primary and metastatic tumor. What I didn’t talk about today just because of time is that MSH3 is a very unique protein that it doesn’t only work in mismatch repair as I highlighted here. It also is a partner for homologous recombination after DNA double strand breaks. And it turns out there is a difference in loss of heterozygosity (LOH) largely because of the MSH3 defect between the primary and metastatic liver. We have a paper under review showing that one of the sites on chromosome 9 is highly enriched for LOH in the metastasis. So to directly answer your question, does frame shift mutation in other things drive metastasis with loss of MSH3? That at least on the surface this does not appear to be the case, unlike classic MSI.

Pasche, Winston-Salem: Very nice presentation. I have two questions, first of all, very interesting EMAST — a new phenotype, do you have any more detail about the clinical phenotype, do you see more liver metastasis to the bone? Peritoneal metastasis? And secondly, you mentioned the worst outcome, is it associated also with resistance to chemotherapy? I understand you may not have a large number but do you see retrospectively for 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or irinotecan or oxaliplatin? Is there anything you are seeing now?

Carethers, Ann Arbor: So on to your second question first so we just published a paper in May in Plus One that looked at 5-FU specifically because we do know that with classic MSI there are more resistant 5-FU. And we did not find a difference for about 230 patients whether they had EMAST or not. And I think the reason is because MSH3 is part of the MSH2 complex, but you also have MSH2-MSH6 complex, and it turns out that we have published several papers that show chemically the strongest recognition of DNA containing 5-FU is recognized by the MSH2-MSH6. So taking out the MSH2-MSH3 complex would theoretically maybe reduce it but in our study that we published, we found no difference in outcome between patients who have EMAST-positive tumors and EMAST-negative tumors with 5-FU therapy. We have not tested specifically in irinotecan or oxaliplatin. Your first question, you have to remind me again.

Pasche, Winston-Salem: Was the pheno-clinical type metastatic poor outcome, and where does the disease go for metastasis?

Carethers, Ann Arbor: Oh, something like 60% of patients with EMAST-positive colorectal cancers show an inflammatory signature that is different than classic MSI. With classic MSI for instance, the tumor presumably occurs and you make these neoantigens and the immune cells come in based on those neoantigens. In the case of EMAST, the inflammation, we don’t know what triggers that, but may occur first and you get secondary EMAST so the paper that we just published on that MSH3 shifts from the nucleus to the cytosol. Turns out it was all IL-6 driven and it turns out in data, that we haven’t published yet but are close to publishing, it turns out that MSH3’s structure has very unique sequences for nuclear localization and nuclear export and we’ve since mutated these and shown these in abstract form that we can prevent the movement of MSH3 depending on where we mutate the nuclear export or nuclear localization signals. And then an additional paper we recently published looked at a number of different cytokines. Clearly it was IL-6 because we blocked the IL-6 receptor, IL-6 induced STAT3 dimerization that blocked the shift, and we actually put a constitutively-active STAT3 into the cell and that kicked MSH3 out of the nucleus. So we clearly showed it was that pathway but what triggers the inflammation first is not quite clear. These patients tend to be more advanced stage, they tend to be in stage 3 and stage 4, and in fact in many of them have metastasis compared to those without EMAST, their metastatic signature is much higher.

Hromas, Gainesville: One would think with these hypermutable tumors that there would be a lot of novel antigens expressed and there would be a magnificent immune response restricting these tumors growth but there is not. I wonder if they express a lot of PD-1 and if the checkpoint inhibitors, recently approved, would be efficacious against these?

Carethers, Ann Arbor: For classic MSI, Louis Diaz’s group from Hopkins just published that data and showed that for classic MSI — this is loss of MLH1, MSH2, etc., they do respond to PD-1 because they do make a lot of new antigens. Now for EMAST, with the previous question, that is not known but my suspicion is that it’s not susceptible to PD-1 blockade. So MSI probably happens early and drives the pathogenesis of the tumor by taking out TGF-beta, taking out ACVR2, taking out BAX, etc. — taking out all of these things that have coding microsatellites and making these new antigens. EMAST is a later phenomenon. You have already developed the tumor, now you have some inflammatory milieu and then EMAST comes in secondarily and then enhances the ability for the tumors to metastasize. So a lot of the protective inflammation would’ve been needed before then and you are to a point now where this phenomenon comes later in the pathogenesis. This is what I think.

Zeidel, Boston: Wonderful work, wonderful presentation for those of us who don’t work in this area. As someone who thinks about epithelia, this relationship between inflammation and the development of cancer and various epithelia is striking, and you may have come upon a mechanism that may be generalizable beyond the colon. Is there evidence that this mechanism might be working in other forms of epithelial cancer?

Carethers, Ann Arbor: Well it’s not just in cancer but non-cancer. I will tell you in the paper we just published, we looked at some lung cancer cells as well as non- transformed cells and we see the shift of MSH3. We also have some data that we have not published yet about pancreatitis, and ulcerative colitis. It turns out that most of them show this EMAST signature and it looks like it is all MSH3 driven. So it even occurs in non-cancer. I think if you get a burn on your hand, this happens, however, because I think MSH3 comes later. Does this prime something for a tumor in a non-cancerous cell? That’s a good question. We have seen MSH3 lost in the epithelia from inflammatory polyps in hamartomatous polyps as well. I think this happens as a general phenomenon. In the cancer case it probably hijacks the phenomena and makes it more aggressive. And now you have to hit stem cells or you got to hit a cancer cell. And if you hit a normal cell that normally stops whatever is healing, you probably won’t see a long term effect.

Zeidel, Boston: Is this often repetitive inflammation?

Carethers, Ann Arbor: Yes, correct. In fact by the IL-6 data that we have, and I didn’t show, if you remove the IL-6, MSH3 moves back into the nucleus and it’s the same protein because we have done cycloheximide experiments so it’s clear that this is a shuttling protein. We just need to figure out how it shuttles.

Berger, Cleveland: I think you said the EMAST is more common or is very common in African-American patients.

Carethers, Ann Arbor: So I didn’t say that here but I have published it, and the answer is yes. It’s about twice as common in African-American patients with colorectal cancer in the cohorts we have. We think that contributes to some of the poor outcome.

Berger, Cleveland: So is this the case in a local population or nationally or internationally? And I was also going to ask do you think that contributes to the disparity?

Carethers, Ann Arbor: Yes, to answer the second question, yes I think it drives to the disparity. The population we published in June of this year in collaboration with the University of North Carolina, the cohort was 503 patients with colorectal cancer. That cohort had 45% African Americans collected as a population base amongst 33 counties in North Carolina. So I can’t say it was a national population but it was certainly a statewide population cohort.

Schwartz, Aurora: John, I was wondering if you could comment on the mechanisms of mismatch repair as it relates to the aging process and also as they relate to telomere length?

Carethers, Ann Arbor: So, I will say that there hasn’t been a direct study of that, but I will tell you of one that is sporadic, particularly in sporadic colorectal cancers. The hypermethylation in MLH1 tends to occur in older patients. So for Lynch syndrome, we have a germline and we have one already knocked out. The average age is 40-42 years range. In patients who have a hypermethylated MLH1, which is the majority of MSI sporadic colorectal cancers, they tend to be slightly older, so the average age of colon cancer in the United States is close to 70 years. These patients tend to be slightly over 70 and these tend to be more women with colorectal cancer, typically older with that hypermethylation. Now could that be really due to telomere length.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dietlein F, Thelen L, Jokic M, Jachimowicz RD, et al. A functional cancer genomics screen identifies a druggable synthetic lethal interaction between MSH3 and PRKDC. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:592–605. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carethers JM, Koi M, Tseng-Rogenski S. EMAST is a form of microsatellite instability that is initiated by inflammation and modulates colorectal cancer progression. Genes. 2015;6:185–205. doi: 10.3390/genes6020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grady WM, Carethers JM. Genomic and epigenetic instability in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1079–99. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carethers JM, Jung BH. Genetics and genetic biomarkers in sporadic colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1177–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. http://www.nobelprize.org . Accessed November 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carethers JM, Hawn MT, Chauhan DP, Luce MC, et al. Competency in mismatch repair prohibits clonal expansion of cancer cells treated with N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:199–206. doi: 10.1172/JCI118767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tajima A, Hess MT, Cabrera BL, Kolodner RD, et al. The mismatch repair complex hMutS alpha recognizes 5-fluoruracil-modified DNA: implications for chemosensitivity and resistance. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1678–84. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tajima A, Iwaizumi M, Tseng-Rogenski S, Cabrera BL, et al. Both hMutSα and hMutSβ DNA mismatch repair complexes participate in 5-fluoruracil cytotoxicity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwaizumi M, Tseng-Rogenski S, Carethers JM. DNA mismatch repair proficiency executing 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:756–64. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.8.17169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung B, Doctolero RT, Tajima A, Nguyen AK, et al. Loss of activin receptor type 2 protein expression in microsatellite unstable colon cancers. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:654–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung H, Young DJ, Lopez C, Le T-AT, et al. Mutation rates of TGFBR2 and ACVR2 coding microsatellites in human cells with defective DNA mismatch repair. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung H, Lopez CG, Young DJ, Lai JF, et al. Flanking sequence specificity determines coding microsatellite heteroduplex and mutation rates with defective DNA mismatch repair. Oncogene. 2010;29:2172–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung H, Lopez CG, Holmstrom J, Young DJ, et al. Both microsatellite length and sequence context determine frameshift mutation rates in defective DNA mismatch repair. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 Jul 1;19(13):2638–2647. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devaraj B, Lee A, Cabrera BL, Miyai K, et al. Relationship of EMAST and microsatellite instability among patients with rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1521–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S-Y, Chung H, Devaraj B, Iwaizumi M, et al. Elevated microsatellite alterations at selected tetranucleotide repeats are associated with morphologies of colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1519–25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang DK, Ricciardiello L, Goel A, Chang CL, et al. Steady-state regulation of the human DNA mismatch repair system. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18424–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veigl ML, Kasturi L, Olechnowicz J, Ma AH, et al. Biallelic inactivation of hMLH1 by epigenetic gene silencing, a novel mechanism causing human MSI cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8698–702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, Graff JR, et al. Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6870–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kane MF, Loda M, Gaida GM, et al. Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:808–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, et al. A National Cancer Institute workshop on microsatellite instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carethers JM. Proteomics, genomics and molecular biology in the personalized treatment of colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1648–50. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1942-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carethers JM. DNA testing and molecular screening for colon cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carethers JM, Pham T-TT. Mutations of transforming growth factor beta 1 type II receptor, BAX, and insulin-like growth factor II receptor genes in microsatellite unstable cell lines. In Vivo. 2000;14:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwitalle Y, Kloor M, Eiermann S, Linnebacher M, et al. Immune response against frameshift-induced neopeptides in HNPCC patients and healthy HNPCC mutation carriers. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:988–97. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, et al. PD-1 Blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, Thibodeau SN, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:247–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carethers JM, Smith EJ, Behling CA, Nguyen L, et al. Use of 5-fluorouracil and survival in patients with microsatellite unstable colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:394–401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carethers JM, Murali B, Yang B, Doctolero RT, et al. Influence of race on microsatellite instability and CD8+ T cell infiltration in colon cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carethers JM. Screening for colorectal cancer in African Americans: determinants and rationale for an earlier age to commence screening. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:711–21. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3443-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carethers JM. One colon lumen but two organs. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:411–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hampel H, Frankel WL, Martin E, Arnold M, et al. Screening for the Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1851–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carethers JM. Differentiating Lynch-like from Lynch syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:602–4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carethers JM, Stoffel EM. Lynch syndrome and Lynch syndrome mimics: the growing complex landscape of hereditary colon cancer. World J Gastroenterology. 2015;21:9253–61. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mensenkamp AR, Vogelaar IP, van Zelst-Stams WA, Goossens M, et al. Somatic mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 are a frequent cause of mismatch-repair deficiency in Lynch syndrome-like tumors. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:643–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haraldsdottir S, Hampel H, Tomsic J, Frankel WL, et al. Colon and endometrial cancers with mismatch repair deficiency can arise from somatic, rather than germline, mutations. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1308–16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamaya Y, Guarinos C, Tseng-Rogenski SS, Iwaizumi M, et al. Efficacy of 5-fluorouracil adjuvant therapy for patients with EMAST-positive stage II/III colorectal cancers. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tseng-Rogenski S, Chung H, Wilk MB, Zhang S, et al. Oxidative stress induces nuclear-to-cytosol shift of hMSH3, a potential mechanism for EMAST in colorectal cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tseng-Rogenski S, Hamaya Y, Choi D, Carethers JM. Interleukin 6 alters localization of hMSH3, leading to DNA mismatch repair defects in colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:579–89. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campregher C, Schmid G, Ferk F, Knasmüller S, et al. MSH3-deficiency initiates EMAST without oncogenic transformation of human colon epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia M, Choi C, Kim HR, Daoud Y, et al. Association between recurrent metastasis from stage II and III primary colorectal tumors and moderate microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:48–50. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]