Abstract

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) and dissociative disorders (DDs) are described in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and tenth edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) as 2 categorically distinct diagnostic categories. However, several studies indicate high levels of co-occurrence between these diagnostic groups, which might be explained by overlapping symptoms. The aim of this systematic review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the research concerning overlap and differences in symptoms between schizophrenia spectrum and DDs. For this purpose the PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases were searched for relevant literature. The literature contained a large body of evidence showing the presence of symptoms of dissociation in SSDs. Although there are quantitative differences between diagnoses, overlapping symptoms are not limited to certain domains of dissociation, nor to nonpathological forms of dissociation. In addition, dissociation seems to be related to a history of trauma in SSDs, as is also seen in DDs. There is also evidence showing that positive and negative symptoms typically associated with schizophrenia may be present in DD. Implications of these results are discussed with regard to different models of psychopathology and clinical practice.

Key words: schizotypy, psychosis, trauma, phenomenology, differential diagnosis

Introduction

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) and dissociative disorders (DDs) are described as 2 distinct diagnostic categories in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-51) and the tenth edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-102). These distinct diagnoses are a reflection of categorical models of psychopathology.3 Both manuals characterize SSDs by positive symptoms (eg, hallucinations), negative symptoms (eg, alexithymia), catatonia, and disorganization. DDs are characterized by dissociation, which is described as a disruption in the usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception.1 Pathological dissociation is often seen as a reaction to trauma and has been described broadly to include depersonalization (feeling detached from oneself) and absorption (being absorbed in your own mental imagery) but also more narrowly as fragmentation of the identity.4

The distinction between SSDs and DDs was weaker in the past.5 Bleuler6 described schizophrenia originally as a disorder in which “emotionally charged ideas or drives attain a certain degree of autonomy so that the personality falls into pieces. These fragments can then exist side by side and alternately dominate the main part of the personality, the conscious part of the patient.”(p143). This description is similar to contemporary descriptions of DDs.7 In addition, Bleuler’s rudimentary form of dissociation known as splitting of associations is theoretically close to the modern concept of synthetic metacognition (ie, the ability to synthesize intentions, thoughts, and feelings into complex representations of self), which is impaired in schizophrenia.8 The first 2 versions of the DSM still had a link between SSDs and dissociation. The DSM-I9 stated that schizophrenic reactions can lead to dissociative phenomena(p27) and the DSM-II10 associated “dreamlike dissociation” with acute schizophrenic episodes(p34). Furthermore, up until the mid-20th century depersonalization was important in the diagnosis of schizophrenia,11 but is now seen as a dissociative symptom.

A big change came with the DSM-III,12 which was developed after diagnoses were found to be unreliable due to unclear diagnostic criteria.13,14 The goal of the DSM-III was to remedy this problem by emphasizing reliability.15 One of the changes was that the DSM-III contained a new diagnostic category: the DDs. At the same time the connection between SSDs and dissociation disappeared completely. No changes were made in the DSM-IV and DSM-5 in this regard.

Given the strong focus on classification of psychopathology into DSM categories, the possibility of an overlap between these diagnoses has mostly been neglected. Traditionally, research on SSDs has focused more on biological factors, whereas research on DDs has focused more on life experiences (eg, trauma16). These different perspectives date back to Pierre Janet17 and Emil Kraepelin18; while Janet emphasized the role of trauma in dissociation, Kraepelin emphasized the role of biological factors in dementia praecox (later coined schizophrenia6).

Despite the different theoretical underpinnings between DDs and SSDs, several studies have found surprisingly high co-occurrence of these diagnoses (not to be confused with true comorbidity19,20). While some studies showed no co-occurrence of SSDs and DDs,21 others showed that between 9% and 50% of schizophrenia spectrum patients also meet diagnostic criteria for a DD.22–24 One study showed that in a sample of patients diagnosed with Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) 74.3% also met diagnostic criteria of a SSD, 49.5% met diagnostic criteria for schizoaffective disorder, and 18.7% met diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia.25 In addition, patients with a DD have often had a previous diagnosis of a SSD (between 27% and 41%).26 This co-occurrence is surprisingly high considering the much lower occurrence of the individual diagnoses.27

A question that arises from the shared history and high co-occurrence is whether the categorical distinction between SSDs and DDs is clinically and scientifically the most useful approach. This is an important question since many studies base their inclusion criteria on these classifications and the type of healthcare someone will receive is based on these classifications.15 Although co-occurrence is seen in many diagnoses, this issue is especially relevant for DDs and SSDs because of their shared history. Furthermore, their treatment of choice differs strongly, with a focus on psychotherapy for DDs and on pharmacotherapy for SSDs.28,29 Moreover, treating DDs with antipsychotic medication is usually ineffective29 while psychotic symptoms in DDs decrease with DD treatment.30

In the predominantly categorical approach of the DSM-5, a diagnosis is considered to reflect an underlying disease entity.31 As an alternative, the dimensional model states that symptoms are best conceptualized on a spectrum ranging from healthy to pathological,3,32 and are thus, to a certain extent, also found in healthy controls and patients with other diagnoses. Within this model, co-occurrence is less surprising as diagnoses do not necessarily reflect underlying disease entities but simply combinations of pathological experiences occurring together. Co-occurrence would then reflect 2 (or more) combinations of pathological experiences occurring together instead of 2 or more disease entities occurring together (ie, comorbidity).

The high co-occurrence between SSDs and DDs might be further explained by the network structure model of psychopathology.33 The network structure model states that psychopathological symptoms can cause other symptoms. For example, anxiety can cause sleep problems, which can lead to fatigue, which in turn can increase anxiety and cause feelings of depression.34 In this view a diagnosis does not necessarily reflect a disease entity but rather a network of interacting symptoms. Other factors, such as personality traits and the environment also influence these networks. These networks might be different for different individuals with the same symptoms. Combining the dimensional model with the network structure of psychopathology leads to the prediction that having problems in 1 domain (eg, dissociation) can cause problems in another domain (eg, psychotic symptoms). For example, it has been suggested that dissociative detachment can lead to impaired reality testing, which in turn can cause psychotic symptoms.35

If symptoms can cause other symptoms, the co-occurrence between SSDs and DDs might be best examined on a symptom level. Accordingly, several studies have examined the symptoms of these diagnoses (eg, Renard et al36, O’Driscoll et al37). The aim of the current review is to combine the results of these studies, and give an overview of the extent to which the diagnostic symptoms are unique to one of the 2 diagnoses. Although the diagnoses might differ in other ways, this review focusses on the DSM-5 symptoms because the diagnoses are based on the prevalence of these symptoms. In addition, although there is still some debate on the magnitude,38,39 trauma is generally considered to play a role in the etiology of both DDs40 and SSDs.41 Therefore, we will explore the role of trauma in relation to symptoms. In the discussion the results we will be related to the different models of psychopathology.

Methods

The criteria for systematic reviews as described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement42 were followed for this study. The PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases were searched for literature published between 1980 and March 8, 2016. We limited our search to literature published after 1980, as this was when the DSM-III was published describing SSDs and DDs as 2 distinct diagnostic categories. The search was limited to records in English. The following Boolean search term was used: “(“dissociative disorder” AND (psychosis OR psychotic OR schizotyp* OR hallucinations OR delusions OR “negative symptoms” OR alexithymia OR catatoni* or disorganiz*)) OR (schizophrenia AND (dissocia* OR depersonalization OR derealization)) OR (psychosis AND (dissocia* OR depersonalization OR derealization)) OR (psychotic AND (dissocia* OR depersonalization OR derealization))”.

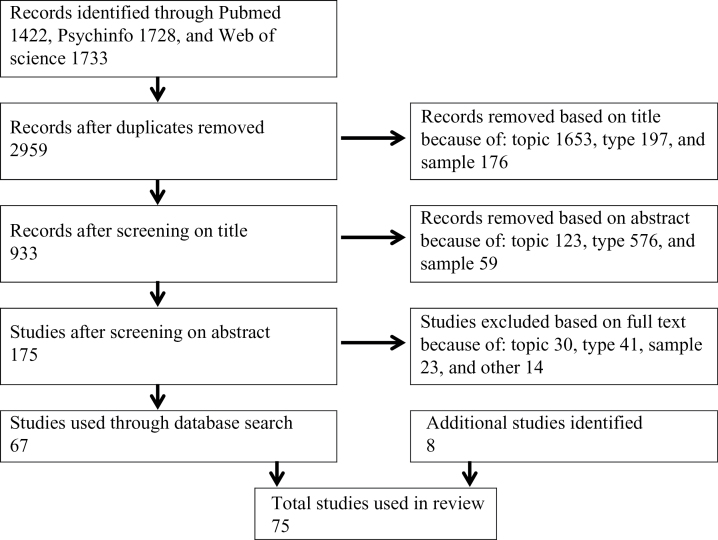

Figure 1 shows the inclusion process through a flow chart. To be included in this review, records had to meet the following criteria: (1) describe a unique empirical study in (2) a sample of adult patients with a DSM or ICD confirmed diagnosis of SSD or DD on (3) symptoms the DSM-5 associates with DDs or SSDs, respectively. Most of the records that were excluded based on topic were found because “dissociation” was used to describe things not being connected instead of as a symptom. Records excluded based on type were, eg, review articles, case reports, and book chapters. Records excluded based on sample did not examine a DD or SSD sample. Other reasons were, eg, using the same dataset as another study or not reporting descriptive statistics. The references of identified articles were examined in order to identify studies that were not found in the original database search.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of systematic search.

Results

Symptoms of Dissociation in SSDs

Several studies examined symptoms of dissociation in schizophrenia spectrum patients through the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES43), which is the most commonly used instrument for measuring dissociation. The questionnaire contains 28 items describing dissociative experiences. The respondent is asked to state how often they had each experience ranging from 0% to 100% of the time, resulting in mean scores ranging from 0 to 100. Mean scores for healthy controls ranged between 4.3843 and 14.8644, whereas mean scores of patients with a DD ranged between 24.9 for depersonalization disorder45 and 57.06 for multiple personality disorder (the term used for DID in DSM-III).43

The prevalence of dissociation in patients with a SSD as measured through the DES is shown in table 1. Most studies found that schizophrenia spectrum patients score significantly higher on dissociation than healthy controls, with mean scores of patients ranging from 11.9 to 44.24.46,47 The pooled mean dissociation scores were calculated from the studies that provided means, SD, and sample sizes (see table 1). Schizophrenia spectrum patients had a pooled mean score of 19.66 and healthy controls of 7.63. The difference between these groups showed a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.04; pooled SD = 11.48). No significant differences were found between schizophrenia spectrum patients and healthy adolescents43,48,49 which is explained by healthy adolescents having more dissociative experiences than healthy controls in general.43,48,50 Moreover, schizophrenia spectrum patients scored significantly lower than DD patients.43,48 Elevated dissociation scores were also found in schizophrenia spectrum patients using the State Scale of Dissociation,51 the Questionnaire of Experiences of Dissociation,52 the Dissociation Tension Scale,53 and the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale.54–57

Table 1.

Dissociative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders as Measured With the DES

| Study | Sample | n | DES Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bernstein and Putnam43 | Schizophreniab | 20 | 20.63e (NA) |

| Ross et al58a | Schizophreniab | 20 | 17.1 (15.3) |

| Fink and Golinkoff59 | Schizophreniab | 11 | 12.6 (NA) |

| Goff et al47a | Psychotic outpatientsb | 61 | 44.24 (30.53) |

| Goff et al60a | Psychotic outpatientsb | 61 | 15.82 (14.16) |

| Horen et al61a | Schizophreniac | 19 | 20.4 (19.6) |

| Yargic et al62 | Schizophreniab | 23 | 11.61e (NA) |

| Putnam et al48a | Schizophreniab | 65 | 17.6 (16.0) |

| Moise and Leichner23 | Schizophreniac | 53 | 18.7 (NA) |

| Spitzer et al63a | Schizophreniad | 27 | 15.8 (10.5) |

| Yargiç et al64a | Schizophreniac | 20 | 15.6 (2.7) |

| Offen et al65a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 36 | 25.2 (14.6) |

| Offen et al66a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 26 | 23.1 (16.6) |

| Welburn et al67 | Schizophreniac | 9 | 17.98 (NA) |

| Brunner et al49a | Schizophrenia spectrumd | 26 | 14 (10.6) |

| Ross and Keyes24 | Schizophreniac | 60 | 18.94 (NA) |

| Dorahy et al68a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 9 | 22.7 (13.8) |

| Merckelbach et al69a | Schizophreniac | 22 | 21.5 (16.5) |

| Hlastala and McClellan70a | Schizophreniac | 27 | 26.9 (21.5) |

| Bob et al71a | Schizophreniac | 82 | 15.7 (8.5) |

| Schäfer et al46a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 30 | |

| Admission | 21.0 (17.7) | ||

| Stabilized | 11.9 (9.9) | ||

| Vogel et al72a | Schizophreniac | 87 | 14.73 (12.87) |

| Modestin et al73a | Schizophrenia spectrumd | 43 | 9.9 (6.8) |

| Perona-Garcelán et al74 | Schizophreniac | 51 | 17.01 (NA) |

| Dorahy et al75a | Schizophreniac | 34 | 21.54 (16.11)f |

| Vogel et al76a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 80 | 16.76 (12.44) |

| Sar et al77a | Schizophreniac | 70 | 18.1 (16.6) |

| Bob et al78a | Schizophreniac | 58 | 14.21 (11.17) |

| Perona-Garcelan et al79a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 37 | 19.00 (13.38) |

| Schäfer et al80a | Schizophrenia spectrumd | 145 | |

| Admission | 19.2 (15.0) | ||

| Stabilized | 14.1 (12.0) | ||

| Varese et al44a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 45 | 30.81 (12.52) |

| Renard et al36a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 49 | 28.83 (19.71) |

| Perona-Garcelán et al56a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 71 | 18.7 (13.42) |

| Pec et al81 | Schizophreniac | 31 | 13.7 (NA) |

| Laferriere-Simard et al82a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 50 | 18.12 (12.68) |

| Bozkurt Zincir et al83a | Schizophrenia spectrumc | 54 | 23.35 (23.7) |

| Tschoeke et al21a | Schizophreniac | 21 | 19.9 (17.8) |

| Oh et al84 | Schizophreniac | 68 | 17.0 (NA)f |

Note: DES, Dissociative Experiences Scale; NA, not reported in paper.

aUsed to calculate pooled mean: Mp = 19.66, SDp = 14.12, total n = 1375.

bDiagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition.

cDiagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

dDiagnosis according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, tenth edition.

eMedian score.

fScore according to DES-T.

The DES is often divided in the following 3 subscales (for a discussion, see Giesbrecht et al85): amnesia (eg, finding things among your belongings you don’t remember buying), depersonalization and derealization (eg, looking in the mirror and not recognizing yourself), and absorption and imaginative involvement (eg, being so involved in a fantasy or daydream that it feels as though it were really happening).86 In addition, 8 items of the DES are thought to assess pathological dissociation; these items form the dissociative taxon (DES-T) and are thought to better predict DDs than the traditional DES.86 Table 2 shows the results of studies examining the different symptom clusters of dissociation. While symptoms of dissociation in schizophrenia are not limited to 1 aspect of dissociation, absorption, and imaginative involvement are more prevalent than amnesia, and depersonalization/derealization.23,46,74,80 In addition, schizophrenia spectrum patients scored significantly lower than DID patients on the DES-T,75 but still higher than healthy controls.69,75,80 Pathological levels of dissociation have also been found in schizophrenia spectrum patients through using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D87). Patients diagnosed with a SSD showed pathological levels of dissociative amnesia (34%), depersonalization (48%), derealization (22%), identity confusion (46%), and identity alteration (56%).22

Table 2.

Mean (SD) Scores on Symptom Clusters of Dissociation in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder

| Study | n | Symptom Cluster | Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moise and Leichner23 | 53 | DES | ||||

| Amnesia | 5.7 (NA) | |||||

| Absorption | 15.7 (NA) | |||||

| Depersonalization | 7.0 (NA) | |||||

| Schäfer et al46 | 30 | DES | Admission | Stabilized | ||

| Amnesia | 13.2 (15.0) | 5.8 (7.9) | ||||

| Absorption | 25.6 (21.5) | 15.3 (10.6) | ||||

| Depersonalization | 24.7 (25.3) | 13.3 (15.2) | ||||

| Schäfer et al80 | 145 | DES | Admission | Stabilized | ||

| Amnesia | 13.3 (14.5) | 8.9 (11.0) | ||||

| Absorption | 25.2 (16.6) | 19.2 (14.2) | ||||

| Depersonalization | 18.1 (18.3) | 13.3 (14.6) | ||||

| Perona-Garcelán et al74 | 68 | DES | With Hallucinations | Former Hallucinations | No Hallucinations | |

| Amnesia | 17.13 (NA) | 9.93 (NA) | 5.97 (NA) | |||

| Absorption | 35.87 (NA) | 24.86 (NA) | 14.98 (NA) | |||

| Depersonalization | 36.24 (NA) | 6.45 (NA) | 1.75 (NA) | |||

| Haugen and Castillo22 | 50 | SCID-D | Pathological levels in: | |||

| Amnesia | 34% | |||||

| Depersonalization | 48% | |||||

| Derealization | 22% | |||||

| Identity confusion | 46% | |||||

| Identity alteration | 56% | |||||

Note: DES, Dissociative Experiences Scale43; NA, not reported in paper; SCID-D, Structured Clinical interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders.88

Two studies compared dissociative symptoms of patients with a SSD at admission with patients in the stable phase (see table 2).46,80 Dissociation scores at admission were similar to other studies in schizophrenia spectrum patients. However, total scores, subscale scores, and DES-T scores were significantly lower after patients were considered stable, suggesting that dissociation was associated with acute psychotic symptoms.80 In addition, no significant difference was found on DES scores between healthy controls and individuals diagnosed with a SSD in remission.73

Several studies examined to what extent dissociation is seen in different subgroups of SSD patients (see table 3). For example, chronic schizophrenia spectrum patients scored higher on dissociation than first episode patients.89 Furthermore, individuals with a diagnosis of psychosis not otherwise specified experienced more dissociation than individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.90 In addition, as confirmed by a recent meta-analysis,91 there seems to be a robust relationship between auditory verbal hallucinations and dissociation.24,44,63,80,92–94 Although weaker than the relationship with hallucinations, there also seems to be a relationship between dissociation and delusions.47,63,79,95,96 Only 1 study found that patients scoring high on dissociation also scored higher on negative symptoms and general symptoms of psychopathology as assessed with the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS97).76

Table 3.

Dissociation in Different Subgroups of Patients Diagnosed With a Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder

| Study | Sample | n | DES Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goff et al47 | Psychotic outpatientsa | ||

| With delusions of possession | 25 | 58.4 (47.2) | |

| Without delusions of possession | 36 | 34.4 (32.7) | |

| McClellan and McCurry90 | Schizophreniab | 18 | 26.4 (21.0) |

| Schizoaffectiveb | 7 | 18.4 (18.4) | |

| Psychosis NOSb | 11 | 41.2 (12.6) | |

| Glaslova et al98 | Schizophreniaa | ||

| Without atypical psychotic symptoms | 26.9 (21.5) | ||

| With atypical psychotic symptoms | 34.9 (19.4) | ||

| Perona-Garcelán et al74 | Schizophreniab | ||

| With hallucinations | 17 | 27.5 (NA) | |

| Past hallucinations | 16 | 14.65 (NA) | |

| No hallucinations | 18 | 9.19 (NA) | |

| Perona-Garcelan et al79 | Schizophrenia spectruma | 37 | |

| With delusions | 22.28 (15.94) | ||

| Without delusions | 11.22 (9.88) | ||

| Varese et al44 | Schizophrenia spectrumb | ||

| With hallucinations | 15 | 42.59 (11.03) | |

| Past hallucinations | 14 | 26.06 (10.90) | |

| No hallucinations | 16 | 23.93 (14.93) | |

| Braehler et al89 | Schizophrenia spectrumb | ||

| First episode | 62 | 13.01 (13.27) | |

| Chronic | 43 | 21.56 (18.98) |

Note: NA, not reported in paper.

aDiagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

bDiagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition.

Dissociation in Relation to Trauma

Schizophrenia spectrum patients with a self-reported history of trauma experience more dissociation than those without a self-reported history of trauma (Mp = 19.75 and Mp = 13.29, respectively, Cohen’s d = 0.49, see table 4).60,75 These findings were confirmed with objective assessments of trauma history by examining patients who had been exposed to “The Troubles” in Ireland.99 Patients with more than 1 trauma experience more dissociation than those with only 1 trauma, indicating a cumulative effect.100 In addition, schizophrenia patients scoring high on dissociation report significantly more trauma than those scoring low on dissociation.24,77,92 Both schizophrenia patients with and without trauma scored significantly higher on dissociation than healthy controls.72

Table 4.

Dissociation in Relation to Trauma in Patients Diagnosed With a Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder

| Study | Sample | n | Score Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goff et al60 | Psychotic outpatientsa | ||

| With child abuse | 27 | 20.0 (16.1) | |

| Without child abuse | 34 | 12.5 (12.4) | |

| Ross et al101 | Schizophreniaa | ||

| With child abuse | 37 | 21.6 (NA) | |

| Without child abuse | 46 | 8.5 (NA) | |

| Vogel et al72 | Schizophreniab | ||

| With trauma and self-rated PTSD | 14 | 21.0 (15.8) | |

| With trauma, no self-rated PTSD | 43 | 15.0 (12.9) | |

| Without trauma and self-rated PTSD | 30 | 11.4 (11.2) | |

| Perona-Garcelan et al79 | Schizophrenia spectrumb | ||

| With childhood trauma | 15 | 28.01 (17.99) | |

| Without childhood trauma | 22 | 12.85 (8.98) | |

| Dorahy et al75 | Schizophreniab | ||

| With maltreatment | 16 | 32.5 (21.0)c | |

| Without maltreatment | 18 | 11.8 (9.9)c | |

| Vogel et al76 | Schizophrenia spectrumb | ||

| No CPA | 60 | 15.3 (12.2) | |

| Low CPA | 7 | 16.5 (11.6) | |

| Moderate CPA | 6 | 21.9 (14.9) | |

| High CPA | 7 | 25.1 (13.0) |

Note: CPA, childhood physical abuse; DES-T, dissociative taxon; NA, not reported in paper; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

aDiagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition.

bDiagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

cScore according to DES-T.

Dissociation seems to be related to childhood trauma and not adult trauma in SSDs.79 However, the results are mixed with regard to different types of childhood trauma. One study found that dissociation is only related to childhood physical neglect,76 while others have also found relations with emotional abuse,46,102 physical abuse,102 and sexual abuse.80 Finally, 2 studies were found which did not find a relationship between trauma and dissociation in SSDs.93,95

Symptoms of Schizophrenia in DDs

There has been relatively little research on symptoms of schizophrenia in DDs compared to the research done on dissociation in SSDs. Furthermore, interpreting the results can be complicated as some authors argue there is a difference between, eg, true hallucinations and pseudo-hallucinations,103 while others argue there is no clear distinction between these 2 concepts.104 No studies were found that explicitly compared symptoms of patients with healthy controls. A substantial number of studies focused on Schneider’s first-rank symptoms of schizophrenia in DDs. Schneider105 described the following 11 symptoms as characteristic of schizophrenia: auditory hallucinations (audible thoughts, voices arguing, voices commenting); somatic passivity; thought withdrawal, insertion, and broadcasting; delusional perception; and delusions of control (made feelings, drives, and behavior). In the past Schneider’s first-rank symptoms were considered pathognomonic for schizophrenia.2,12,106 Some of these symptoms (ie, voices arguing, voices commenting, and bizarre delusions) were still considered to be pathognomonic in the DSM-IV. However, this has been changed in the DSM-5.

Substantiating the reduced emphasis on Schneider’s first-rank symptoms in schizophrenia, these symptoms have been found to be highly prevalent in dissociative disorders,107 especially in those with a former diagnosis of schizophrenia.108 First-rank auditory hallucinations have been found in 47% to 90% of the patients with a DD.26,109,110 Forty-five percent of the patients with a DD experienced delusions26 although bizarre delusions were uncommon.109 However, delusions of thought withdrawal/insertion and delusions of control were found to be even more common in DID than in schizophrenia.95 Patients with DID on average show between 3.6 and 6.4 first-rank symptoms26,109,111 whereas the general population reported 0.5112 and schizophrenia patients reported 0.9 first-rank symptoms.113 These results show that first-rank symptoms of schizophrenia are more common in DDs.

DID patients have on average more positive symptoms than schizophrenia patients, as assessed with the PANSS.114 Between 16% and 20% of the patients with a DD experience visual hallucinations and more than 70% experience auditory hallucinations.115,116 In addition, DD patients showed elevated scores on the schizophrenia scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory.117

While Honig et al.118 found that auditory hallucinations in samples diagnosed with a DD or a SSD were similar, Dorahy et al.75 found that some characteristics differed. For example, patients with a DD had a younger age of onset, more voices, more often child voices, more often voices commenting to each other, and more often reported the voices would be missed.75 However, the small samples and large amount of variables precluded the use of inferential statistics.

Although there is a paucity of research in this regard, clinical impressions suggest that the diagnoses may be distinguishable on negative and disorganized symptoms. Patients with DID have shown negative symptoms, albeit not as many as schizophrenia patients (17.06114 and 21.0197, respectively). However, it is important to note that, similar to the other diagnostic symptoms, not all patients diagnosed with schizophrenia experience negative symptoms. They are experienced by approximately 58% of the patients.119 DID patients scored higher than schizophrenia patients on the PANSS general psychopathology scale (M = 50.09 and M = 37.74, respectively). Symptoms of alexithymia are seen in schizophrenia120 as well as DDs.121,122 In addition, children diagnosed with a DD reported symptoms of withdrawal and disorganized thinking.116 No additional research on disorganization was found. A case report described 3 patients diagnosed with a DD with severe catatonic symptoms123 In addition, in a mixed trauma patient sample, of which approximately half had a DD, 67% showed catatonic symptoms.124 In this study catatonia was unrelated to dissociation and psychosis. These findings are in line with the DSM 5 de-emphasizing catatonia as an indicator of schizophrenia, removing it as a subtype and introducing the diagnosis catatonia associated with another mental disorder,1 and studies advocating that catatonia should be considered an independent syndrome.125

Discussion

The results of this review show similarities but also differences in symptoms between SSDs and DDs. Patients diagnosed with a DD, on average, experience more dissociative and positive symptoms, whereas patients diagnosed with a SSD, on average, experienced more negative symptoms. Despite these quantitative differences, the literature indicates that DDs and SSDs overlap on many of their diagnostic symptoms. Elevated levels of dissociation have been found in SSDs and several symptoms used to diagnose SSDs are also present in DDs. Furthermore, the variances in scores suggest that there are, eg, individuals diagnosed with a SSD experiencing more dissociation than the average patient with a DD.

If diagnoses reflect distinct disease entities one would expect clear boundaries between diagnoses.126,127 With regard to symptoms, the literature does not reveal such clear boundaries between SSDs and DDs. In an effort to explain the symptom overlap, some authors proposed a new diagnosis or diagnostic subtype having characteristics of both SSDs and DDs.82,128,129 However, the dimensional model3 of psychopathology may provide a more parsimonious explanation for the unclear boundaries. In this model patients can present with symptoms associated with different diagnoses as the symptoms do not necessarily reflect underlying disease entities.

The results are also in line with the network structure of psychopathology,33 which specifically predicts that boundaries between diagnoses will be fuzzy. Symptoms function as a small world network in which symptoms can cause other symptoms.34 For example, it has been suggested that dissociation increases the vulnerability to psychotic experiences,130 whereas paranoid ideation131 and perceptual abnormalities132 increases the vulnerability to dissociation. In addition, dissociation might cause weakened cognitive inhibition, in turn leading to hallucinations and delusions.44 Furthermore, the relationship between varieties of inner speech and hallucination proneness seems to be mediated by dissociation.133 Similarly, the relationship between self-focused attention and hallucinations is mediated by depersonalization.54 Other individual differences such as deficits in reality discrimination and self-focused attention might also play a role in such symptom networks. However, as research using the network model is still in its infancy, the actual presence and appearance of such symptom networks is mostly limited to speculation.

Although the results of this study fit well with a combination of the dimensional model and network structure of psychopathology, they do not disprove the categorical approach. An alternative explanation for the symptom overlap is that patients who should be diagnosed with a DD are often misdiagnosed with a SSD.134 These misdiagnosed patients would obscure the actual differences between the diagnoses. This explanation is, eg, supported by many DID patients having a former diagnosis of SSD.26 Especially in the past, when Schneider’s first rank symptoms were thought to be pathognomonic for schizophrenia, the high occurrence of these symptoms in DDs could have led to misdiagnosis. Limitations in the diagnostic process might still play a role in the symptom overlap. However, when assessed for both diagnoses many patients with a DD concurrently meet the diagnostic criteria for a SSD22–24and vice versa.25 If there are categorically distinct disease entities at present our diagnostic systems are insufficiently sensitive to detect them.

It could thus be argued that the overlap in symptoms is an artifact of the instruments we use,135 eg, due to item overlap.37 The current instruments could simply be limited in their ability to distinguish symptoms of SSDs and DDs from each other.95 This limitation is seen in the following item of the DES: “Some people sometimes find that they hear voices inside their head that tell them to do things or comment on things that they are doing.”136 This item should measure a dissociative symptom but it could be argued that it measures a schizophrenia-related symptom instead. However, it is unlikely that the instruments completely explain the symptom overlap as similar results were found while excluding overlapping items56 and when using different instruments (eg, Wolfradt and Engelmann52, Stiglmayr53). In addition, because our conceptualization of symptoms is closely tied to the way we measure them, limitations in the instruments are directly related to limitations in the symptom concepts we have.

It has actually been questioned whether the concepts of psychosis and dissociation are distinguishable.137,138 It has, eg, been suggested that auditory hallucinations should be conceptualized as dissociative instead of psychotic experiences.139 Not all patients with a psychotic disorder experience auditory hallucinations.140 Furthermore, in addition to being found in nonpsychotic clinical samples, auditory hallucinations are also found in nonclinical samples.141 Thus, auditory hallucinations alone are not necessarily pathological psychotic experiences. Instead, auditory hallucinations can be seen as experiences coming from an individual him/herself but not recognized as such, and might thus better be explained as dissociative experiences.139 On the other hand, dissociation may not be able to account for the distinctive sensory characteristics of all hallucinations.142

It might prove useful to conceptualize symptoms more narrowly than is commonly done. The discussion around dissociation is a good example of this. Should dissociation be defined as broadly as is done with the DES, including absorption and imaginative involvement, or should we conceptualize it more narrowly by emphasizing compartmentalization?4 Although there is overlap between DDs and SSDs on dissociation as measured by the DES, there might be clear differences when focusing on identity fragmentation. In the same vein, it might prove useful to distinguish hallucinations from pseudohallucinations and imagery,103,143,144 and delusions from overvalued ideas.145 Or even more narrowly, eg, by dividing auditory hallucinations into different types of auditory hallucinations146 or based on the characteristics of the hallucinations.75 However, some authors argue that instead of making these subcategories (eg, hallucinations vs pseudohallucinations), conceptualizing symptoms on a continuum is more parsimonious.104,147 For these narrower symptom concepts to be useful there need to be reliable and valid instruments to distinguish them from each other.

As an alternative explanation, the distinct diagnostic categories with overlapping symptoms might be explained by having a different etiology. DDs are generally thought to be caused by childhood trauma,148 whereas SSDs were originally thought to be more biological in nature.149 However, the biopsychosocial model of schizophrenia is nowadays widely accepted and emphasizes both biological and environmental factors in its etiology. In line with this, much evidence shows that trauma also plays an important role in the etiology SSDs.150,151 In addition, biological factors have been suggested to play a role in the etiology of DDs.152 For example, twin studies show that genetic factors explain approximately 50% of the variance in pathological and nonpathological dissociation.153 Moreover, abnormalities in frontal and occipital regions were found in DID patients.154 Similar to SSDs,155–157 abnormalities have also been found in hippocampal and amygdalar volume.158 However, there has been disagreement on the interpretation of these results,159 and they have not been replicated.160 No research was found that directly compared patients diagnosed with a DD with those diagnosed with a SSD on brain functioning. While these studies indicate that, to a certain extent, there is overlap in terms of etiology between SSDs and DDs, additional research that directly compares the etiology of these 2 diagnostic groups is important.

There are factors, other than diagnostic symptoms and etiology, that might play a role in the differentiation between DDs and SSDs, eg, gender and cognitive functioning. Patients with a SSD are more often male,161 whereas patients with a DD are more often female.107,162,163 The decision to diagnose someone with a SSD or DD might be biased by gender.164 This bias could be especially relevant for patients who have symptoms of both diagnoses. Similarly, patients with a SSD often show impairments in cognitive165 and metacognitive functioning.166 Although differences have been reported, eg, in processing speed,85,167 patients with a DD function cognitively on approximately the same level as healthy controls.160,168 Impaired cognitive functioning could simply be a symptom of SSDs that is not seen as a diagnostic symptom. However, the diagnosis someone gets could also be biased by that person’s cognitive functioning. If the 2 diagnostic categories indeed differ in the characteristics of the symptoms (such as the content of hallucinations88,169), cognitive functioning might even influence these characteristics.

A limitation of this literature review is that symptoms that are not described in the DSM-5 were not included. Thus, differences between SSDs and DDs might be found in factors that were not considered in the literature search such as fantasy proneness and suggestibility. With regard to these 2 specific factors, there is some debate on their exact role but both factors have been linked to DDs and SSDs and are thus also nonspecific.38,170–172 However, further research on symptoms that are not described in the DSM-5 as diagnostically relevant might prove useful for better differentiation. A second limitation of this study is that many, if not all, of the factors described in this review are not specific to 1 single diagnosis (eg, alexithymia,173 catatonia174). As a result, both SSDs and DDs show overlap with other diagnoses, eg, with anxiety disorders and depression. However, the shared history between SSDs and DDs makes the similarities between these disorders especially noteworthy. Furthermore, the fact that symptoms are generally nonspecific and that overlap in symptoms is common among many disorders only emphasizes the importance of taking a holistic approach and look at symptom networks separate from the diagnostic classifications we use.

To conclude, a large body of literature indicates the presence of symptoms of dissociation in SSDs. In addition, several studies show that symptoms typically associated with schizophrenia are also found in DDs. These results seem to be more consistent with a combination of the dimensional model and network structure model of psychopathology than with categorical models of psychopathology. However, other factors, such as misdiagnosis, item overlap, and construct overlap might also play a role. Whether or not the diagnoses reflect disease entities, it is important for clinicians to be aware of the similarities between these 2 diagnostic classifications. Patients showing symptoms of both diagnoses might benefit from a combination of treatments. In addition, when a patient does not improve from the treatment of the initial diagnosis it is important to reconsider that diagnosis.

Future research should aim to use network analysis to further clarify this issue. A first step would be to examine which symptoms correlate with each other at a single time point for patients with a SSD or DD to see whether their symptom networks differ from each other. These networks might be different in the characteristics of the symptoms (eg, content of hallucinations75,88,169) or in the exact structure of the symptom network (eg, which symptoms have the strongest connections with other symptoms). Such a study could also test the idea that the diagnoses may be distinguishable on negative, cognitive, and disorganized symptoms. The second step would be to see how these networks change over time on an individual level to examine if the same symptoms predict the emergence other symptoms. A last step would be to experimentally test whether the correlations are indeed a reflection of a causal relationships. As most of the research presented is phenomenological in nature the use of neuroimaging should be considered to investigate which neural correlates of dissociative and psychotic symptoms either converge or involve distinct circuitry. If there are distinct disease entities, differences might, eg, be found in resting state neural complexity,175 and neural activity during working memory176and social cognition tasks.36 The lack of studies on genetic factors that may be linked to dissociative disorders further emphasizes the need of more research in this area.

Acknowledgment

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organisation. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown TA, Barlow DH. Dimensional versus categorical classification of mental disorders in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and beyond: comment on the special section. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nijenhuis ERS, van der Hart O. Dissociation in trauma: a new definition and comparison with previous formulations. J Trauma Dissociation. 2011;12:416–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ross CA. Dissociation in classical texts on schizophrenia. Psychos Psychol Soc Integr Approaches. 2014;6:342–354. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bleuler E. Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. Trans. Zinkin, J New York, NY: International University Press; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moskowitz A, Heim G. Eugen Bleuler’s Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias (1911): a centenary appreciation and reconsideration. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pec O, Bob P, Lysaker PH. Trauma, dissociation and synthetic metacognition in schizophrenia. Act Nerv Super. 2015;57:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moe AM, Docherty NM. Schizophrenia and the sense of self. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sartorius N, Shapiro R, Kimura M, Barrett K. WHO international pilot study of schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1972;2:422–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kendell RE, Cooper JE, Gourlay AJ, Copeland JR, Sharpe L, Gurland BJ. Diagnostic criteria of American and British psychiatrists. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andreasen NC. DSM and the death of phenomenology in America: an example of unintended consequences. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moskowitz A. Schizophrenia, trauma, dissociation, and scientific revolutions. J Trauma Dissociation. 2011;12:347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Janet P. L’Automatisme Psychologique. Paris, France: Félix Alcan; 1889. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kraepelin E. Dementia-Praecox and Paraphrenia (translated by Barkley RM). New York, NY; Huntington; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- 19. First MB. Mutually exclusive versus co-occurring diagnostic categories: the challenge of diagnostic comorbidity. Psychopathology. 2005;38:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaplan B, Crawford S, Cantell M, Kooistra L, Dewey D. Comorbidity, co-occurrence, continuum: what’s in a name? Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32:723–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tschoeke S, Steinert T, Flammer E, Uhlmann C. Similarities and differences in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia with voice hearing. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:544–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haugen MC, Castillo RJ. Unrecognized dissociation in psychotic outpatients and implications of ethnicity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:751–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moise J, Leichner P. Prevalence of dissociative symptoms and disorders within an adult outpatient population with schizophrenia. Dissociation. 1996;9:190–196. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ross CA, Keyes B. Dissociation and schizophrenia. J Trauma Dissociation. 2004;5:69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ellason JW, Ross CA, Fuchs DL. Lifetime Axis I and II comorbidity and childhood trauma history in dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatry Interpers Biol Process. 1996;59:255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ross CA, Miller SD, Reagor P, Bjornson L, Fraser GA, Anderson G. Schneiderian symptoms in multiple personality disorder and schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. Updated edition Leicester and London, UK: The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29. International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation. Guidelines for treating dissociative identity disorder in adults, third revision. J Trauma Dissociation. 2011;12:115–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ellason JW, Ross CA. Two-year follow-up of inpatients with dissociative disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:832–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Walker C. Karl Jaspers on the disease entity: Kantian ideas and Weberian ideal types. Hist Psychiatry. 2014;25:317–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johns LC, van Os J. The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:1125–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ, Schmittmann VD, Epskamp S, Waldorp LJ. The small world of psychopathology. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:91–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allen JGD, Coyne L, Console DA. Dissociative detachment relates to psychotic symptoms and personality decompensation. Compr Psychiatry. 1997;38:327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Renard SB, Pijnenborg M, Lysaker PH. Dissociation and social cognition in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Schizophr Res. 2012;137:219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O’Driscoll C, Laing J, Mason O. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies, alexithymia and dissociation in schizophrenia, a review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:482–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lynn SJ, Lilienfeld SO, Merckelbach H, Giesbrecht T, van der Kloet D. Dissociation and dissociative disorders: challenging conventional wisdom. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012;21:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dalenberg CJ, Brand BL, Gleaves DH, et al. Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. Psychol Bull. 2012;138:550–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dalenberg CJ, Brand BL, Loewenstein RJ, et al. Reality versus fantasy: reply to Lynn et al. (2014). Psychol Bull. 2014;140:911–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lysaker PH, Larocco VA, Lysakera PH, Larocco VA. The prevalence and correlates of trauma-related symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). Phys Ther. 2009;89:873–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174:727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Varese F, Barkus E, Bentall RP. Dissociation mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and hallucination-proneness. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Simeon D, Knutelska M, Nelson D, Guralnik O. Feeling unreal: a depersonalization disorder update of 117 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:990–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schäfer I, Harfst T, Aderhold V, et al. Childhood trauma and dissociation in female patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: an exploratory study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Goff DC, Brotman AW, Kindlon D, Waites M, Amico E. The delusion of possession in chronically psychotic patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Putnam FW, Carlson EB, Ross CA, et al. Patterns of dissociation in clinical and nonclinical samples. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brunner R, Parzer P, Schmitt R, Resch F. Dissociative symptoms in schizophrenia: a comparative analysis of patients with borderline personality disorder and healthy controls. Psychopathology. 2004;37:281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fagioli F, Dell’Erba A, Migliorini V, Stanghellini G. Depersonalization: physiological or pathological in adolescents? Compr Psychiatry. 2015;59:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krüger C, Mace CJ. Psychometric validation of the State Scale of Dissociation (SSD). Psychol Psychother. 2002;75(Pt 1):33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wolfradt U, Engelmann S. Depersonalization, fantasies, and coping behavior in clinical context. J Clin Psychol. 2003;55:1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stiglmayr C, Schimke P, Wagner T, et al. Development and psychometric characteristics of the Dissociation Tension Scale. J Pers Assess. 2010;92:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Perona-Garcelan S, Carrascoso-Lopez F, Garcia-Montes JM, et al. Depersonalization as a mediator in the relationship between self-focused attention and auditory hallucinations. J Trauma Dissociation. 2011;12:535–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cernis E, Dunn G, Startup H, et al. Depersonalization in patients with persecutory delusions. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Perona-Garcelán S, García-Montes JM, Ductor-Recuerda MJ, et al. Relationship of metacognition, absorption, and depersonalization in patients with auditory hallucinations. Br J Clin Psychol. 2012;51:100–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gonzalez-Torres MA, Inchausti LL, Aristegui M, et al. Depersonalization in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, first-degree relatives and normal controls. Psychopathology. 2010;43:141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ross CA, Norton GR, Anderson G. The Dissociative Experience Scale: a replication study. Dissociation. 1988;1:21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fink DL, Golinkoff M. MPD, borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia: a comparative study of clinical features. Dissociation. 1990;3:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Goff DC, Brotman AW, Kindlon D, Waites M, Amico E. Self-reports of childhood abuse in chronically psychotic patients. Psychiatry Res. 1991;37:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Horen SA, Leichner PP, Lawson JS. Prevalence of dissociative symptoms and disorders in an adult psychiatric inpatient population in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 1995;40:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yargic LI, Tutkun H, Sar V. Reliability and validity of the turkish version of the Dissociative Experiences Scale. Dissociation. 1995;8:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Spitzer C, Haug HJ, Freyberger HJ. Dissociative symptoms in schizophrenic patients with positive and negative symptoms. Psychopathology. 1997;30:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yargiç LI, Sar V, Tutkun H, Alyanak B. Comparison of dissociative identity disorder with other diagnostic groups using a structured interview in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Offen L, Thomas G, Waller G. Dissociation as a mediator of the relationship between recalled parenting and the clinical correlates of auditory hallucinations. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003;42:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Offen L, Waller G, Thomas G. Is reported childhood sexual abuse associated with the psychopathological characteristics of patients who experience auditory hallucinations? Child Abus Negl. 2003;27:919–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Welburn KR, Fraser GA, Jordan SA, Cameron C, Webb LM, Raine D. Discriminating dissociative identity disorder from schizophrenia and feigned dissociation on psychological tests and structured interview. J Trauma Dissociation. 2003;4:109–130. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dorahy MJ, Middleton W, Irwin HJ. Investigating cognitive inhibition in dissociative identity disorder compared to depression, posttraumatic stress disorder and psychosis. J Trauma Dissociation. 2004;5:93–110. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Merckelbach H, à Campo J, Hardy S, et al. Dissociation and fantasy proneness in psychiatric patients: a preliminary study. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hlastala SA, McClellan J. Phenomenology and diagnostic stability of youths with atypical psychotic symptoms. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bob P, Glaslova K, Susta M, Jasova D, Raboch J. Traumatic dissociation, epileptic-like phenomena, and schizophrenia. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006;27:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vogel M, Spitzer C, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. The role of trauma and PTSD-related symptoms for dissociation and psychopathological distress in inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2006;39:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Modestin J, Hermann S, Endrass J. Schizoidia in schizophrenia spectrum and personality disorders: role of dissociation. Psychiatry Res. 2007;153:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Perona-Garcelán S, Cuevas-Yust C, García-Montes JM, et al. Relationship between self-focused attention and dissociation in patients with and without auditory hallucinations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dorahy MJ, Shannon C, Seagar L, et al. Auditory hallucinations in dissociative identity disorder and schizophrenia with and without a childhood trauma history: similarities and differences. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:892–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Vogel M, Spitzer C, Kuwert P, Möller B, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. Association of childhood neglect with adult dissociation in schizophrenic inpatients. Psychopathology. 2009;42:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sar V, Taycan O, Bolat N, et al. Childhood trauma and dissociation in schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2010;43:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bob P, Susta M, Glaslova K, Boutros NN. Dissociative symptoms and interregional EEG cross-correlations in paranoid schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Perona-Garcelan S, Garcia-Montes JM, Cuevas-Yust C, et al. A preliminary exploration of trauma, dissociation, and positive psychotic symptoms in a Spanish sample. J trauma dissociation. 2010;11:284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Schäfer I, Fisher HL, Aderhold V, et al. Dissociative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: relationships with childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pec O, Bob P, Raboch J. Dissociation in schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:487–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Laferriere-Simard M-C, Lecomte T, Ahoundova L. Empirical testing of criteria for dissociative schizophrenia. J Trauma Dissociation. 2014;15:91–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bozkurt Zincir S, Yanartas O, Zincir SSB, et al. Clinical correlates of childhood trauma and dissociative phenomena in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85:417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Oh HY, Kim D, Kim Y. Reliability and validity of the Dissociative Experiences Scale among South Korean patients with schizophrenia. J Trauma Dissociation. 2015;16:577–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Giesbrecht T, Lynn SJ, Lilienfeld SO, Merckelbach H. Cognitive processes in dissociation: an analysis of core theoretical assumptions. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:617–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Waller NG, Putnam FW, Carlson EB. Types of dissociation and dissociative types : a taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:300–321. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Steinberg M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Steinberg M, Cicchetti D, Buchanan J, Rakfeldt J, Rounsaville B. Distinguishing between multiple personality disorder (dissociative identity disorder) and schizophrenia using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994;182:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Braehler C, Valiquette L, Holowka D, et al. Childhood trauma and dissociation in first-episode psychosis, chronic schizophrenia and community controls. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. McClellan J, McCurry C. Early onset psychotic disorders: diagnostic stability and clinical characteristics. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;8(suppl 1):I13–I19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pilton M, Varese F, Berry K, Bucci S. The relationship between dissociation and voices: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;40:138–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Vogel M, Meier J, Grönke S, et al. Differential effects of childhood abuse and neglect: mediation by posttraumatic distress in neurotic disorder and negative symptoms in schizophrenia? Psychiatry Res. 2011;189:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Vogel M, Schatz D, Spitzer C, et al. A more proximal impact of dissociation than of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder on schneiderian symptoms in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ghoreishi A, Shajari Z. Reviewing the dissociative symptoms in patients with schizophreniaand their association with positive and negative symptoms. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2014;8:13–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Laddis A, Dell PF. Dissociation and psychosis in dissociative identity disorder and schizophrenia. J Trauma Dissociation. 2012;13:397–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Perona-Garcelan S, Carrascoso-Lopez F, Garcia-Montes JM, et al. Dissociative experiences as mediators between childhood trauma and auditory hallucinations. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Glaslova K, Bob P, Jasova D, Bratkova N, Ptacek R. Traumatic stress and schizophrenia. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 2004;11:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mulholland C, Boyle C, Shannon C, et al. Exposure to “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland influences the clinical presentation of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;102:278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Álvarez M-J, Masramon H, Peña C, et al. Cumulative effects of childhood traumas: polytraumatization, dissociation, and schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J. 2014;51:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ross CA, Anderson G, Clark P. Childhood abuse and the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:489–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Holowka DW, King S, Saheb D, Pukall M, Brunet A. Childhood abuse and dissociative symptoms in adult schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;60:87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Telles-Correia D, Moreira AL, Gonçalves JS. Hallucinations and related concepts—their conceptual background. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Van Der Zwaard R, Polak MA. Pseudohallucinations: a pseudoconcept? A review of the validity of the concept, related to associate symptomatology. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Schneider K. Clinical Psychopathology. 3rd ed. Trans. Hamilton MW, Anderson EW. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 106. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. 4th ed., text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ross CA, Heber S, Norton GR, Anderson G. Differences between multiple personality disorder and other diagnostic groups on structured interview. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177:487–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ross CA, Norton GR. Multiple personality disorder patients with a prior diagnosis of schizophrenia. Dissociation Prog Dissociative Disord. 1988;1:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Kluft PR. First-rank symptoms as a diagnostic clue to multiple personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Boon S, Draijer N. Multiple personality disorder in The Netherlands: a clinical investigation of 71 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Sar V, Yargiç LI, Tutkun H. Structured interview data on 35 cases of dissociative identity disorder in Turkey. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1329–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Ross CA, Joshi S. Schneiderian symptoms and childhood trauma in the general population. Compr Psychiatry. 1992;33:269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Tikka SK, Yadav S, Nizamie SH, Das B. Schneiderian first rank symptoms and gamma oscillatory activity in neuroleptic naïve first episode schizophrenia : a 192 channel EEG study. Psychiatry Investig. 2014;11:467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ellason JW, Ross CA. Positive and negative symptoms in dissociative identity disorder and schizophrenia: a comparative analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Coons PM, Bowman ES, Milstein V. Multiple personality disorder. A clinical investigation of 50 cases. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176:519–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Hornstein NL, Putnam FW. Clinical phenomenology of child and adolescent dissociative disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Bliss EL. A symptom profile of patients with multiple personalities, including MMPI results. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984;172:197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Honig A, Romme MA, Ensink BJ, Escher SD, Pennings MH, DeVries MW. Auditory hallucinations: a comparison between patients and nonpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Bobes J, Arango C, Garcia-Garcia M, Rejas J. Prevalence of negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders treated with antipsychotics in routine clinical practice: findings from the CLAMORS study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. van ‘t Wout M, Aleman A, Bermond B, Kahn RS. No words for feelings: alexithymia in schizophrenia patients and first-degree relatives. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Simeon D, Giesbrecht T, Knutelska M, Smith RJ, Smith LM. Alexithymia, absorption, and cognitive failures in depersonalization disorder: a comparison to posttraumatic stress disorder and healthy volunteers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Steffen A, Fiess J, Schmidt R, Rockstroh B. “That pulled the rug out from under my feet!”—adverse experiences and altered emotion processing in patients with functional neurological symptoms compared to healthy comparison subjects. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Sarkar P, Patra B, Sattar FA, Chatterjee K, Gupta A, Walia TS. Dissociative disorder presenting as catatonia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:176–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Ross CA, Browning E. The relationship between catatonia and dissociation: a preliminary investigation. J Trauma Dissociation. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Fink M, Shorter E, Taylor MA. Catatonia is not schizophrenia: Kraepelin’s error and the need to recognize catatonia as an independent syndrome in medical nomenclature. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:314–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Abrams DJ, Rojas DC, Arciniegas DB. Is schizoaffective disorder a distinct categorical diagnosis? A critical review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:1089–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Anckarsäter H. Beyond categorical diagnostics in psychiatry: scientific and medicolegal implications. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2010;33:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Ross CA. Schizophrenia: Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment. Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 129. Vogel M, Braungardt T, Grabe HJ, Schneider W, Klauer T. Detachment, compartmentalization, and schizophrenia: linking dissociation and psychosis by subtype. J Trauma Dissociation. 2013;14:273–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Allen JD, Lolafaye C. Dissociation and vulnerability to psychotic experience the DES and MMPI-2. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Espirito Santo H, Pio-Abreu JL. Demographic and mental health factors associated with pathological dissociation in a Portuguese sample. J Trauma Dissociation. 2008;9:369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Postmes L, Sno HN, Goedhart S, van der Stel J, Heering HD, de Haan L. Schizophrenia as a self-disorder due to perceptual incoherence. Schizophr Res. 2014;152:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Alderson-Day B, McCarthy-Jones S, Bedford S, et al. Shot through with voices: dissociation mediates the relationship between varieties of inner speech and auditory hallucination proneness. Conscious Cogn. 2014;27:288–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Bliss EL. Multiple personalities. A report of 14 cases with implications for schizophrenia and hysteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:1388–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Schäfer I, Aderhold V, Freyberger HJ, Spitzer C. Dissociative symptoms in schizophrenia. In: Moskowitz A, Schäfer I, Dorahy MJ, eds. Psychosis, Trauma and Dissociation: Emerging Perspectives on Severe Psychopathology. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2009:151–163. [Google Scholar]

- 136. Carlson EB, Putnam FW, Ross CA, et al. Validity of the Dissociative Experiences Scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: a multicenter study. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1030–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Watson D. Dissociations of the night: individual differences in sleep-related experiences and their relation to dissociation and schizotypy. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Merckelbach H, Rassin E, Muris P. Dissociation, schizotypy, and fantasy proneness in undergraduate students. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:428–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Moskowitz A, Corstens D. Auditory hallucinations: psychotic symptom or dissociative experience? J Psychol Trauma. 2007;6:35–63. [Google Scholar]

- 140. Suhail K, Cochrane R. Effect of culture and environment on the phenomenology of delusions and hallucinations. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48:126–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. van Os J, Hanssen M, Bijl R V., Ravelli A. Strauss (1969) revisited: a psychosis continuum in the general population? Schizophr Res. 2000;45:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Aleman A, Larøi F. Hallucinations: The Science of Idiosyncratic Perception. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 143. Turner MA. A short note on pseudo-hallucinations. Psychopathology. 2014;47:469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Moreira-Almeida A. Assessing clinical implications of spiritual experiences. Asian J Psychiatr. 2012;5:344–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Mountjoy RL, F Farhall J, L Rossell S. A phenomenological investigation of overvalued ideas and delusions in clinical and subclinical anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. McCarthy-Jones S, Thomas N, Strauss C, et al. Better than mermaids and stray dogs? subtyping auditory verbal hallucinations and its implications for research and practice. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(suppl 4):275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Wearne D, Genetti A. Pseudohallucinations versus hallucinations: wherein lies the difference? Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23:254–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Dorahy MJ, Brand BL, Sar V, et al. Dissociative identity disorder: an empirical overview. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48:402–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Klerman GL. The evolution of a scientific nosology. In: Shershow JC, ed. Schizophrenia: Science and Practice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978:99–121. [Google Scholar]

- 150. van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BPF. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:661–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Sierra M, Nestler S, Jay E-L, Ecker C, Feng Y, David AS. A structural MRI study of cortical thickness in depersonalisation disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2014;224:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Jang KL, Paris J, Zweig-Frank H, Livesley WJ. Twin study of dissociative experience. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Sar V, Unal SN, Ozturk E. Frontal and occipital perfusion changes in dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2007;156:217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Aleman A, Kahn RS. Strange feelings: do amygdala abnormalities dysregulate the emotional brain in schizophrenia? Prog Neurobiol. 2005;77:283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Adriano F, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. Hippocampal volume reduction in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. 2012;18:180–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Radulescu E, Ganeshan B, Shergill SS, et al. Grey-matter texture abnormalities and reduced hippocampal volume are distinguishing features of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2014;I:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Vermetten E, Schmahl C, Lindner S, Loewenstein RJ, Bremner JD. Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:630–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Smeets T, Jelicic M, Merckelbach H. Reduced hippocampal and amygdalar volume in dissociative identity disorder: not such clear evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Weniger G, Lange C, Sachsse U, Irle E. Amygdala and hippocampal volumes and cognition in adult survivors of childhood abuse with dissociative disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Salem JE, Kring AM. The role of gender differences in the reduction of etiologic heterogeneity in schizophrenia. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18:795–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Goff DC, Simms CA. Has multiple personality disorder remained consistent over time? A comparison of past and recent cases. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Tabassum K, Farooq S. Sociodemographic features, affective symptoms and family functioning in hospitalized patients with dissociative disorder (convulsion type). J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Fish V. Some gender biases in diagnosing traumatized women. In: Caplan PJ, Cosgrove L, eds Bias in Psychiatric Diagnosis. A Project of the Association for Women in Psychology. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson; 2004:213–220. [Google Scholar]

- 165. Barch DM, Ceaser A. Cognition in schizophrenia: core psychological and neural mechanisms. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Lysaker PH, Vohs J, Hamm J a, et al. Deficits in metacognitive capacity distinguish patients with schizophrenia from those with prolonged medical adversity. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;55:126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Guralnik O, Giesbrecht T, Knutelska M, Sirroff B, Simeon D. Cognitive functioning in depersonalization disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:983–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Rossini ED, Schwartz MA, Braun BG. Intelectual functioning of inpatients with dissociative identity disorder and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Steinberg M, Siegel HD. Advances in assessment: the differential diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder and schizophrenia. In: Moskowitz A, Schäfer I, Dorahy MJ, eds. Psychosis, Trauma and Dissociation: Emerging Perspectives on Severe Psychopathology. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008:177–189. [Google Scholar]

- 170. Peters MJ V, Moritz S, Tekin S, Jelicic M, Merckelbach H. Susceptibility to misleading information under social pressure in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:1187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Van Heugten - Van der Kloet D, Huntjens R, Giesbrecht T, Merckelbach H. Self-reported sleep disturbances in patients with dissociative identity disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder and how they relate to cognitive failures and fantasy proneness. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Giesbrecht T, Merckelbach H, Geraerts E. The dissociative experiences taxon is related to fantasy proneness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:769–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Leweke F, Leichsenring F, Kruse J, Hermes S. Is alexithymia associated with specific mental disorders? Psychopathology. 2011;45:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Tesón A, et al. Catatonia in depression: prevalence, clinical correlates, and validation of a scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;60:326–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Bob P, Susta M, Chladek J, Glaslova K, Fedor-Freybergh P. Neural complexity, dissociation and schizophrenia. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:HY1–HY5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Egner T, Jamieson G, Gruzelier J. Hypnosis decouples cognitive control from conflict monitoring processes of the frontal lobe. Neuroimage. 2005;27:969–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]