Abstract

Hallucinations constitute one of the 5 symptom domains of psychotic disorders in DSM-5, suggesting diagnostic significance for that group of disorders. Although specific featural properties of hallucinations (negative voices, talking in the third person, and location in external space) are no longer highlighted in DSM, there is likely a residual assumption that hallucinations in schizophrenia can be identified based on these candidate features. We investigated whether certain featural properties of hallucinations are specifically indicative of schizophrenia by conducting a systematic review of studies showing direct comparisons of the featural and clinical characteristics of (auditory and visual) hallucinations among 2 or more population groups (one of which included schizophrenia). A total of 43 articles were reviewed, which included hallucinations in 4 major groups (nonclinical groups, drug- and alcohol-related conditions, medical and neurological conditions, and psychiatric disorders). The results showed that no single hallucination feature or characteristic uniquely indicated a diagnosis of schizophrenia, with the sole exception of an age of onset in late adolescence. Among the 21 features of hallucinations in schizophrenia considered here, 95% were shared with other psychiatric disorders, 85% with medical/neurological conditions, 66% with drugs and alcohol conditions, and 52% with the nonclinical groups. Additional differences rendered the nonclinical groups somewhat distinctive from clinical disorders. Overall, when considering hallucinations, it is inadvisable to give weight to the presence of any featural properties alone in making a schizophrenia diagnosis. It is more important to focus instead on the co-occurrence of other symptoms and the value of hallucinations as an indicator of vulnerability.

Key words: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychosis, nonclinical

Introduction

The personal, cultural, and clinical significances of hallucinations have changed in the 200 years since they were defined by Esquirol as “the intimate conviction of actually perceiving a sensation for which there is no external object.”1,2 There is a growing recognition that hallucinatory experiences attend a wide variety of psychiatric diagnoses and can be part of everyday experience for people who do not meet criteria for mental illness. For the experiencer, hallucinations can have important personal meanings, and for clinicians, they are also significant in varied ways, including as diagnostic symptom and as factors which may impact on functioning and prognosis, and therefore potentially the necessity of treatment.

Since the earliest clinical texts, auditory hallucinations have been closely linked to schizophrenia.3,4 Hallucinations constitute one of the 5 domains of abnormality of schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders in DSM-5. Although not diagnostic of schizophrenia when occurring in isolation, the presence of persistent auditory hallucinations is sufficient for a diagnosis of Other Specified Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorder, if it is combined with clinically significant distress or functional impairment (ref.5, p. 122).

The emphasis on the clinical significance of hallucinations in DSM-55 requires closer examination given our growing understanding of hallucinations that feature outside of psychosis. It is increasingly recognized that hallucinations occur with significant frequency in other psychiatric (eg, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], personality disorders) and medical conditions (neurodegenerative conditions and eye disease) and that they are especially predictive of multimorbid psychopathology.6,7 A predominant view, however, is that some features of hallucinations may distinguish schizophrenia and related disorders from other conditions. Candidate distinguishing features that have become important diagnostically include negative and derogatory auditory hallucinations; command hallucinations; voices heard conversing about the individual in the third person; and location in external space.4,5,8

Given the status of hallucinations as diagnostic markers in DSM-5, there is a pressing need to establish their specificity to psychotic disorders, particularly through comparison of their featural properties across different population groups. This exercise is also essential if we are to understand how hallucinations function in cognitive and neuroscientific models of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia.

The present article attempts to meet this challenge through a systematic review of empirical studies that have made direct comparisons of hallucinations involving 2 or more population groups (one of which included schizophrenia). Our focus is on visual and auditory hallucinations, because these experiences figure more prominently in schizophrenia research than other modalities of hallucination. We place particular emphasis on whether hallucinations share points of commonality or divergence between different groups. Because diagnostic criteria inevitably focus on self-report rather than objective markers, the bulk of studies have reported on the phenomenological features of hallucinations. Too few studies have directly compared cognitive or neuroimaging variables between 2 and more groups for meaningful analyses, although helpful syntheses of the literature exist.9–12 In this article, we present a direct contrast of hallucination features across clinical groups with a view to identifying features specific to schizophrenia. First, we briefly consider the different conditions and groups in which hallucinations have been reported.

Disorders and conditions in which hallucinations present

There are many disorders and conditions (including nonpathological cases) in which hallucinations have been reported (supplementary material table 1, adapted13–15).

Psychotic experiences occur in around 4%–7% of the general population,16,17 proving transitory in around 80% of cases.18 In this group, incidence of hallucinations varies with developmental stage, appearing with relatively high prevalence in children (8%19) and older adults (community 1%–5%; residential care 63%20), and some adults on a continuum of hallucination proneness. Hallucinations also occur transiently in situations causing extreme physiological or psychological stress (fatigue, sensory deprivation, bereavement, etc.).21,22

Hallucinations co-occur with toxin-, alcohol-, and drug-related conditions that affect the central nervous system and involve the cortical sensory areas. These include intoxication with stimulants, hallucinogenic drugs, and cannabis, and withdrawal from substances including alcohol.23 Medication-induced hallucinations also result from drug abuse or occur as side effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drugs,24 antimalarial medication,25 and antiparkinsonian drugs. In these cases, hallucinations usually disappear after withdrawal of the substance.

Hallucinations are associated with a range of medical conditions. Conditions causing interference with, or damage to, the peripheral sensory pathways can produce hallucinations. For example, acquired deafness is a common cause for (auditory) hallucinations, as is eye disease or lesions of afferent visual pathways for visual hallucinations.26,27 Endocrine-related metabolic disorders including disorders of thyroid function28 and Hashimoto disease29 can produce hallucinations, as can deficiencies in D and B12 vitamins.30,31 Other medical conditions associated with hallucinations include chromosomal disorders such as Prader–Willi syndrome,32 autoimmune disorders,33 and acquired immunodeficiency disorders such as HIV/AIDS,34 and sleep disorders such as narcolepsy.35 Neurological events such as tumors,36,37 traumatic brain injuries,38 epilepsy,39 and cardiovascular events may also cause hallucinations where activity involves the brainstem regions and areas involving the temporal, occipital, or temporo-parietal pathways. Hallucinations are also fairly common in neurodegenerative conditions, particularly in Parkinson’s disease40 and dementia with Lewy bodies.41

Finally, hallucinations are reported in a range of major psychiatric conditions. In addition to psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizotypal personality traits, schizoaffective disorders, other specified spectrum disorders, etc.), hallucinations and other psychotic experiences occur in affective disorders such as bipolar (mixed, manic, depressed) and unipolar depression42; personality disorders; PTSD; and anorexia and bulimia nervosa.43

In summary, because hallucinations occur in a number of different clinical groups, they can be considered nonspecific for psychotic disorders. A categorical approach reliant solely on the presence of hallucinations is therefore not helpful as a diagnostic aid.

How do hallucinations present across diagnostic classes?

In this section, we consider data as they inform on points of commonality and divergence across diagnostic classes of psychiatric illness, with a particular focus on comparisons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. A predominant aim is to determine which, if any, features of hallucinations are pathognomonic: that is, specific to schizophrenia (as the “prototypical” psychotic disorder) and not reported in any other population group.

Methods

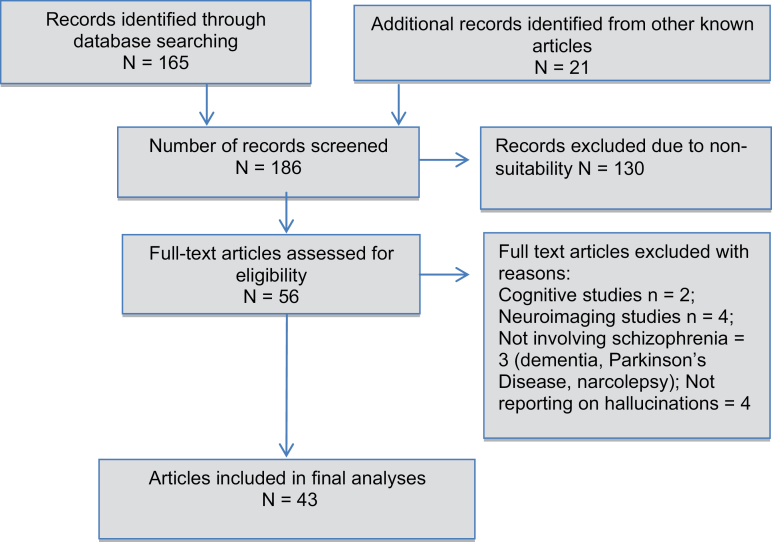

To answer these questions, a search was carried out in Medline for English-language articles and book chapters containing the following terms (Hallucinat* OR Psychot* Symptom*) AND (Compar* OR Differen* OR Similarit* OR Contrast*), without date restrictions. Inclusion criteria included empirical articles involving direct contrasts between 2 and more population groups with hallucinations, where one of these groups included schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Exclusion criteria were as follows: single case studies and reviews, studies reporting on “hallucination proneness” as a continuous variable, and publication in languages other than English. The search was conducted on June 20, 2016, and revealed 165 articles, to which 21 additional articles were added from known articles and cross-referencing. Title and abstracts, and subsequently the entire articles, were scanned to ascertain whether they fulfilled the criteria (see figure 1 for PRISMA diagram). A total of 56 articles met the criteria.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram.

The great majority of articles (90.1%) demonstrated a focus on featural or clinical characteristics of hallucinations (supplementary material table 2). The remaining articles reporting solely on imaging data (n = 4) or cognitive processes (n = 2) were excluded. Seven further articles were excluded for not involving a schizophrenia group or not reporting on hallucinations specifically.

In total, 43 articles were reviewed (see table 1). Articles involving direct comparisons with schizophrenia included the following 4 major groups: (1) nonclinical groups (general population,44–48 religious experiences49,50; total 7 studies); (2) drug- or alcohol-related (substances) conditions51–59 (9 studies); (3) medical and neurological conditions (tinnitus,60 epilepsy,61,62 narcolepsy,35 other medical and neurological causes53,63–66; total 9 studies); and (4) psychiatric disorders (affective disorders,8,42,53,64,66–70 borderline personality disorder,71–74 PTSD,75,76 dissociative identity disorder,44,77 anorexia78; total 18 studies). There were a further 2 articles on attenuated psychosis (ultra high risk [UHR]),79,80 which were classed in the psychiatric group. Noticeably absent were direct comparisons with Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative conditions. Given this important gap, we chose to include one recent review comparing visual hallucinations in schizophrenia to those in Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, and eye disease81 (classed in the medical and neurological category).

Table 1.

Phenomenological Features of Hallucinations Across 4 Population Groups (%) and Comparisons With Schizophrenia (Mean %82)

| Characteristic Features of Hallucinations | Schizophrenia | Nonclinical | Substances | Medical, Neurologic | Other Psychiatric | Groups Showing the Same Features as Schizophrenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form | ||||||

| Presence of auditory verbal hallucinations (“voices”) | 75% | ±58% | ±50% | ±32% | 46%–57% | Nonclinical44,45,48 (including evangelical born-again Christians50); alcohol dependence disorder,51,56 cocaine withdrawal55; tinnitus,60 epilepsy,62,83 medical or neurological condition,63 narcolepsy35; Parkinson’s disease81; bipolar disorder,42,69,70 borderline personality disorder,73,74 dissociative identity disorder,77 PTSD75 |

| Predominance of auditory (A) over visual (V) hallucinations | 75% A, 30% V | Nil | Nil | ±32% A, ±10% V | ±28% A, ±15% V | Temporal lobe epilepsy,62,83 medical or neurological condition63,84; bipolar disorder42,67 |

| Hallucinations in 3 or more sensory modalities | 60% | Nil | ±16% | ±20% | ±76% | Cocaine abuse,55 LSD intoxication,54 alcohol dependence disorder53; bipolar disorder,66,70 dissociative identity disorder,77 narcolepsy35 |

| Duration: up to several hours at a time | 66% | ±47% | ?% | ±70% | 77%–93% | Nonclinical44 (including evangelical born-again Christians50); alcohol dependence disorder,53 cocaine abuse55; tinnitus,60 temporal lobe epilepsy62; dissociative identity disorder,44 borderline personality disorder73 |

| Perceived to be vivid and real | 80% | ?% | ±26% | ±48% | 54%–100% | Nonclinical28,44,48; alcohol dependence disorder,51 cocaine abuse55,56,59; LSD intoxication58; tinnitus,60 temporal lobe epilepsy,62,83 medical or neurological condition63; PTSD,76 bipolar disorder,64,66,69 dissociative identity disorder,44,77 borderline personality disorder72–74 |

| Originating in external space | 50% | ±57% | ±70% | ±37% | 60%–83% | Nonclinical28,44; alcohol dependence disorder51; tinnitus,60 medical or neurological condition63; dissociative identity disorder,77 PTSD,76,77 bipolar disorder,8,64,66,69 borderline personality disorder72–74 |

| Third-person hallucinations, running commentary, voices commenting | 65% | 20%–41% | 20%–60% | 10%–41% | 40%–80% | Nonclinical28,44; cannabis abuse57; alcohol dependence disorder53,56; medical or neurological condition,63,84 temporal lobe epilepsy62,83; affective disorders,69 dissociative identity disorder,44 PTSD,76 borderline personality disorder,74 narcolepsy35 |

| Hallucinations shared with other people (eg, voices “heard” by others) | 50% | Nil | Nil | ±62% | ±27% | Epilepsy,84 neurological condition66; bipolar disorder66,69 |

| Contents | ||||||

| Negative and hostile content | 60% | 43%–53% | ?% | ±33% | 58%–93% | Nonclinical44,48 (including evangelical born-again Christians50); cocaine withdrawal,55 alcohol dependence disorder56; temporal lobe epilepsy62; Parkinson’s disease81; medical and neurological condition,63 affective disorders mixed69; PTSD,75,76 borderline personality disorder72,73; dissociative identity disorder44,77 |

| Personifications and attributions to spiritual or magical identities | 61% | 50%–100% | 20%–60% | ±50% | ±97% | Nonclinical28,46 (including evangelical born-again Christians50); cocaine withdrawal55; alcohol dependence disorder56; medical or neurological condition63,64; temporal lobe epilepsy62; PTSD76 |

| Assigned significance (eg, hallucinations have meaning) | 72% | ?% | ±42% | ±76% | ?% | Nonclinical (including evangelical born-again Christians50 and other religious voice-hearers49); cocaine withdrawal,55 LSD intoxication54; temporal lobe epilepsy62; bipolar disorder,64 borderline personality disorder71 |

| Commands to commit aggressive or injurious acts | 84% | Nil | ±4% | ?% | 62%–82% | Amphetamine withdrawal and dependence,52,55 alcohol substance disorder56; temporal lobe epilepsy62; bipolar disorder,69 PTSD,76 dissociative identity disorder77 |

| Interference and lack of control | ||||||

| Interference with daytime functions | 47% | Nil | ±30% | ?% | ±84% | Cocaine withdrawal55; tinnitus60; temporal lobe epilepsy62; PTSD,75,76 borderline personality disorder,72,73 bipolar disorder,64 narcolepsy35 |

| Lack of perceived control | 78% | Nil | ?% | ±53% | ±78% | Alcohol substance disorder51; tinnitus,60 temporal lobe epilepsy,62,83 medical or neurological condition64,66; borderline personality disorder,72,73 bipolar disorder66,69 |

| Other clinical and epidemiological features | ||||||

| Recurrent course of hallucinations (>1 y, multiple episodes) | 60% | ±89% | Nil | ?% | ±35% | Nonclinical47,48; epilepsy62,83; PTSD,76 bipolar disorder68,85 |

| Hearing or vision loss | ?% | Nil | Nil | ?% | ?% | Tinnitus,60 medical or neurological condition,65,66 neurodegenerative disease81; UHR psychosis79 |

| Trauma and neglect | 50% | ±50% | Nil | Nil | ±50% | Nonclinical population44,47; dissociative identity disorder44,77; borderline personality disorder72,73 |

| External triggers | 50% | Nil | Nil | Nil | ±80% | Affective disorders,69 dissociative identity disorder44,77 |

| Internal triggers | 60% | ?% | ?% | ?% | ±60% | Nonclinical population44; tinnitus60; all substances are internal triggers; PTSD76 |

| Family history of psychiatric illness | 30% | Nil | ±23% | ±30% | ±40% | Epilepsy83; cannabis abuse57; anorexia nervosa78 |

| Age of onset in late teen to early 20s | 18–24 | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | |

| Feature commonality with schizophrenia (number and %) | n/a | 11/21 = 52% | 14/21 = 66% | 18/21 = 85% | 20/21 = 95% | |

Note: n/a, not applicable; LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; UHR, ultra high risk. “Nil” findings are shaded in bold. “?%” indicates that percentages were not reported in the articles reviewed.

Results

Findings are organized around the 21 most commonly described features of hallucinations in schizophrenia, sorted according to modality, form, content, interference, and lack of control,86 and other clinical and epidemiological features. Percentages (when available) are shown in table 1. An entry of “nil” indicates that this feature has not been reported in this diagnostic group.

Overall, psychiatric disorders shared the most features with schizophrenia (20/21, 95%); followed by medical/neurological disorders, with 18/21 features of commonality (85%); and by substance-related conditions (11/21, 66%). Nonclinical groups shared approximately half of all features (11/21, 52%).

Auditory (verbal and other sounds) hallucinations occurred in all 4 major groups, with the highest prevalence (outside schizophrenia) reported in evangelical born-again Christians (58%)50 and bipolar disorder (57%).42 The predominance of auditory hallucinations over other modalities (eg, visual hallucinations) is commonly viewed as indicative of schizophrenia,5 although this profile is also reported in medical conditions including temporal lobe epilepsy,83 as well as in bipolar disorder.42

Multiple modalities of hallucinations (>3, although not simultaneously) were originally thought to be distinctive for schizophrenia,64,66 but this pattern also occurs in the context of drugs and alcohol,55 and narcolepsy.35 Psychiatric conditions such as bipolar disorder and dissociative identity disorder77 report several modalities of hallucinations (typically 2 or 3), but generally fewer than schizophrenia (where individuals may report 4 or 5 distinct modalities).

Specific formal parameters of hallucination (persistent voices, vividness and realism, and origin in external space) are also displayed in the 4 major groups. For example, continuous voices over several hours among those who have hallucinations have been reported in nonclinical individuals at rates of 47%,44 tinnitus (70%),60 dissociative identity disorder (93%44), and affective disorders (77%69). Similarly, (visual) hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease may last for hours at a time.81 The experience is highly vivid and perceived to be real in 26% of alcohol withdrawal cases,56 bipolar disorder (100%69), and PTSD (54%76). Voices originating in external space are not pathognomonic of schizophrenia, occurring at rates of 57% in nonclinical groups,44 37% in tinnitus,60 60% in PTSD,76 83% in bipolar disorder,64,66,69 and 67% in dissociative identity disorder.44

Third-person hallucinations and voices commenting or conversing with each other do not distinguish between groups. Voices commenting are reported in nonclinical groups (41% of those who hear voices)44 and in patients with narcolepsy (17%),35 dissociative identity disorder (80%),44 and affective disorders (54%).69 Similarly third-person hallucinations are reported at rates of 20% in nonclinical groups,44,45 10% in narcolepsy,35 25%–60% in alcohol withdrawal,53,56 and 40% in affective disorders.69 Approximately one-third of individuals with schizophrenia expect their voices to be heard by others,87 a feature additionally observed in bipolar disorder and organic psychosis.66,84

With regard to contents, negative, accusatory, or derogatory voices occur in all groups, eg, 93% of individuals with dissociative identity disorder with hallucinations, 58% of affective disorders,69 and 62% of PTSD.76 Negative contents are also common in both auditory and visual hallucinations in alcohol withdrawal56,88 and in neurodegenerative conditions.81 Negative voices occur less frequently in nonclinical groups, although they are still reported in approximately half44,48 of these individuals.

Similarly, personification and attribution of hallucinations did not distinguish between groups. Nonclinical groups often attribute their hallucinations to a relative or acquaintance,45 to deceased persons, and to religious figures,46 whereas personification to supernatural entities is more common in religious experiences,50 substance-related conditions,55 and psychiatric disorders.76 In Parkinson’s disease and dementia, hallucinations are attributed to people who may be familiar or not, alive or deceased, or to guardian angels.81

Hallucinations assigned special significance are common in the context of drugs,54 temporal lobe epilepsy,62 bipolar disorder,64 and borderline personality disorder.71 Such special significances are also reported in religious experiences,49,50 although the interpretation is more positive than for those in schizophrenia.

Voices giving commands to commit aggressive or injurious actions are observed in most groups. For example, in a PTSD sample, 62% of those hearing voices were commanded to self-harm, and 46% had acted on command hallucinations.75,76 Command hallucinations are also reported in 82.3% of individuals with bipolar disorder.69 No data are reported on this feature in nonclinical individuals.

Interference with daily life, and lack of perceived control, is a prominent issue in all but nonclinical groups. For example, daytime interference is reported in 84% of individuals with dissociative identity disorder.44 Similarly, lack of control over the onset and content of hallucinations is common with substance-related, medical, and neurological causes,60 as well as borderline personality disorder72 and bipolar disorder.44 By contrast, nonclinical groups report significantly less distress or daytime interference than individuals with schizophrenia,44 and greater levels of control.45

A persistent course of hallucinations (lasting for more than 1 year or multiple episodes) has been demonstrated in nonclinical groups,47 epilepsy,83 bipolar disorder,85 and PTSD in which hallucinations can persist for longer than 1 year in the majority of cases.76 In Leudar and coworkers’ sample of 13 nonclinical individuals,48 recurrent voice hallucinations were reported in 89% and had been ongoing on average for longer than 4 years.

Finally, shared epidemiological and clinical features of hallucinations include the following: (1) hearing or vision loss as a vulnerability factor for hallucinations, which is additionally reported in UHR groups,79 neurological conditions including tinnitus,60 and neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease81; (2) negative life events, such as emotional neglect and trauma, reported in nonclinical groups (50%)44 and psychiatric conditions including dissociative identity disorder (50%)44,77 and borderline personality disorder72,73; (3) triggers that include exogenous (external) situations in dissociative identity disorder (at rates of 80%44) and affective disorders69 but not nonclinical groups44, and endogenous (internal) triggers such as sadness, stress, and tiredness reported in the nonclinical group,44 PTSD (60%),76 and tinnitus60; and (4) family history of psychiatric illness, which is displayed across all major groups except nonclinical groups.

One feature of hallucinations appears to distinguish schizophrenia from other groups. Age of onset of hallucinations in schizophrenia is typically from the late teens to early 20s. Direct comparison demonstrates that an earlier age of onset (<12 years) is more frequent in dissociative identity disorder (33%) and nonclinical groups (40%) than in schizophrenia (11%).44 Daalman et al45 showed a mean age of onset of 12.4 years for nonclinical individuals compared to 21.4 years in schizophrenia. Hallucinations in affective disorders, neurological disorders, and alcohol-related conditions, by contrast, appear predominantly in middle or older age.56,62

Discussion of findings

Our systematic review demonstrates that almost all phenomenological, clinical, and epidemiological features of hallucinations in schizophrenia are also represented in other population groups, with the sole exception of age of onset.

Points of similarity and difference among diagnostic classes

Our findings did not support the notion that some features of hallucinations are uniquely diagnostic of schizophrenia.4,8,89 Auditory “verbal” hallucinations, which are vivid, occur frequently, and are experienced as coming from outside of the head, are present in all 4 major groups considered here (nonclinical, substances, medical or neurological, and psychiatric). Examples include hallucinations linked to religious experiences,49,50 dissociative identity disorder,44,77 and temporal lobe epilepsy.62,90 Of note, voices originating in external space occurred in half of nonclinical voice hearers,44 one-third of individuals with tinnitus,60 and 60%–83% of individuals with PTSD,76,77 bipolar disorder,69 and dissociative identity disorder.44 The highlighting of Schneider’s first-rank symptoms (including third-person hallucinations and voices conversing) as indicative of schizophrenia4 was not supported, with these features occurring in nonclinical samples at rates of 20%–40%,44,45 narcolepsy (10%–17%),35 alcohol withdrawal (26%–60%),53,56 affective disorders (20%–55%),69 and dissociative identity disorder (80%).44

Similarly, the widely held notion that negative voices are indicative of psychosis91 was not confirmed. Negative and derogatory (visual and/or auditory) hallucinations occurred in all (clinical and nonclinical) groups. Similarly, the way in which hallucinations are personified and assigned special significance (ie, seen as personally meaningful) is also a feature of other psychiatric conditions (bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, PTSD)64,71,76 and temporal lobe epilepsy.62 In nonclinical groups (such as evangelical born-again Christians), it is common for voices to be interpreted as having religious meaning.49,50

One feature of interest is hallucination frequency, which is often difficult to assess empirically (e.g., ref.50) and is confounded both with symptom incidence and hallucination duration (see table 1). Although some studies show hallucinations to be more frequent in schizophrenia in relation to a comparison group (ref.10,80), others show hallucinations in comparison groups to have an objectively high rate of occurrence (e.g., refs66,69,76). In the absence of further data, frequent hallucinations can thus not be considered to be a diagnostic feature of schizophrenia. Altogether, the featural properties of hallucinations carry minimal information about the condition in which it occurs.

Only one feature, age of onset, was identified as of potential interest for distinguishing schizophrenia from other groups. We note, however, that this relates to a continuous variable rather than a clear presence or absence of any hallucination feature. Its diagnostic value is further limited given the small number of studies that have considered it transdiagnostically, the potential confound of prodromal symptoms predating the onset of frank psychosis, potential unreliability of reports due to difficulties in remembering a first experience that might have occurred many years ago, and the relatively high variance in age of onset even in schizophrenia.

With regard to points of rarity among other groups, one feature deserving of more research concerns external triggers for hallucination. External factors including a lack or an excess of external stimulation (eg, social contact), are a trigger in 80% of schizophrenia cases,82 and similar rates have been reported in dissociative identity disorder and affective disorders.44,69 By contrast, there is an absence of information regarding external triggers in nonclinical groups on the basis of the one direct comparison study reviewed here.44 We note however that one small qualitative study investigating “out-of-the-ordinary” experiences including hallucinations92 showed triggering by social isolation.

Points of rarity for major diagnostic groups

We also examined points of rarity for each major group. A historical focus on the symptoms of psychosis has reinforced a “schizophrenia-centric” approach to hallucination descriptions, yet our analysis allows an examination of each disorder group individually. Specifically, table 1 enables an inspection of how hallucination features are shared among diagnostic groups, indicating possible points of rarity.

With regard to hallucinations in psychiatric disorders (particularly affective disorders, borderline personality disorder, dissociative identity disorder, and PTSD), table 1 suggests that no hallucination feature differentiated them from schizophrenia except age of onset (95% feature commonality). This supports findings of studies reporting on the overlap in genetic, neurobiological, and clinical features between schizophrenia and these psychiatric disorders.93,94

Hallucinations caused by the abuse or withdrawal of substances (toxins, drugs, alcohol) differ from schizophrenia in the following features: visual hallucinations are more common than auditory hallucinations; the course is not recurrent but proximally related to substance ingestion; and hearing or vision loss is not a cause.

A discussion on hallucinations in medical and neurological conditions is complicated by the heterogeneity of this group (incorporating tinnitus, epilepsy, narcolepsy, neurodegenerative conditions, and other medical and neurological conditions). Interestingly, conditions such as epilepsy and tinnitus share up to 85% (18/21) of features with schizophrenia and appear almost indistinguishable in form and content,60,62,84,90 except for clinical and epidemiological correlates such as trauma and external triggers. The absence of information on triggers may merely reflect the lack of direct comparison studies reporting on this issue. For example, photic stimulation, TV, and video games are triggers for complex partial seizures.95 Overall, too few direct comparisons exist for confident conclusions regarding unique hallucination features in medical and neurological conditions.

Reflecting its relative newness as a field of research attention, only 7 studies involving nonclinical individuals met inclusion criteria. Hallucinations in this group shared 11 out of 21 features with schizophrenia (52%), including vivid and frequent voices, third-person hallucinations, personification, a recurrent course of hallucinations, and an increased risk for adverse negative events. A potential point of rarity distinguishing this nonclinical group is that such experiences receive a more positive interpretation compared to psychiatric disorders. Although contents may be negative96 in up to 50% of cases,44 voices are more often positive (93% of cases compared with 83% in schizophrenia and 67% in dissociation identity disorder) and are largely controllable. The affective reaction to voices is also more positive in the nonclinical group. In the sample of evangelical born-again Christians,50 voices are actively encouraged and given positive religious meanings. Such positive interpretations are presumably consistent with reported reductions in daytime interference, agitation, and fear, and with the fact that such individuals do not seek care. Several studies have now described the profile of nonclinical voice hearers as varying on a continuum with voices in schizophrenia.10,47 Additional differences identified here include that (1) other modalities of hallucination (eg, visual or body related) may be as common as voices (or even more so); (2) such individuals experience a lesser total number of different modalities of hallucinations (<3); and (3) hearing loss or visual deficits do not appear as a frequent cause.

Finally, table 1 was examined to establish whether any hallucination features are shared among all but one diagnostic groups, suggesting a point of rarity for that exception group. This criterion was met only for the nonclinical group. Four out of 21 (21%) hallucination features were shared among all other groups except this one (hallucinations in ≥3 sensory modalities, commands to commit aggressive or injurious acts, interference with daytime functions, and lack of perceived control).

Interaction between features

The above analysis suggests that featural properties of hallucinations alone are unlikely to be able to support a diagnosis of schizophrenia. More important than the presence or absence of any specific hallucination features, however, is arguably the question of how those features interact with other symptoms. Two issues need to be distinguished here: the question of whether the specific profile of symptoms and symptom features creates distinctive signatures for different diagnoses, and the question of how symptoms interact as they co-occur. In relation to the first question, table 1 indicates how a transdiagnostic comparison of hallucination features may indicate distinctive profiles for particular disorders. Clearly, in distinguishing schizophrenia from (say) toxin-related disorders, other clinical information (such as patient history of toxin use) will be highly relevant. Further research in transdiagnostic comparison of symptom features (beyond their mere absence or presence) may therefore be of value in improving differential diagnosis.

With regard to the second question, there has recently been considerable interest in the view that psychotic symptoms occur transdiagnostically and that features of psychosis may occur on a continuum as an extended phenotype in the general population.7 With the application of methodologies such as graph theory to psychosis research, new methodologies are becoming available to better understand psychosis as it operates within a network of interacting symptoms.97 Most importantly, such methods demonstrate how, through investigation of interactions between variables, it is possible to understand how hallucinations may function or impact differently in different diagnostic groups according to what roles they play in the network.

Clinical applications

This review yields an important conclusion with regard to the diagnostic value of hallucinations. It concludes that it is inadvisable to give weight to the presence of any featural properties of hallucination alone when making a diagnosis. For example, negative and hostile voices talking in the third person and causing distress may equally be present in a patient with schizophrenia, epilepsy, brain tumor, or PTSD. However, this conclusion does not entail that hallucinations are clinically uninformative. First, clinical observation suggests that some conditions have their own distinctive hallucination signature providing clues regarding their underlying causes (eg, “cocaine bugs”55). Second, the greater clinical significance of hallucinations may lie in their value in designating the severity of psychopathology. The presence of hallucinations indicates increased risk of poor outcomes transdiagnostically, including multimorbid nonpsychotic disorders, suicidality, neurocognitive deficits, and low functioning.6,81 Functional disability is also higher in those with hallucinations than those without hallucinations in the context of psychiatric disorders such as dissociative identity disorder,44 PTSD,75 anorexia nervosa,78 and narcolepsy. In such cases, hallucinations may point to a more severe form of the disorder. Alternatively, hallucinations may be an experience that restricts patients’ recovery while not being intrinsic to that particular disorder, just as other factors such as educational level and social support will influence prognosis. Altogether, the value of hallucinations may be greater as an indicator of vulnerability or risk than as a diagnostic marker.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations apply to the present study. Our inclusion criteria limit the parameters and features investigated to those that were reported in these 43 articles. The absence of a feature in table 1 does not entail that it is a not a feature of the disorder, but rather indicates a lack of evidence on which to make comparisons. The range of features reviewed here is also necessarily limited. First, features tend to cluster in similar dimensions (physical properties, control, frequency, complexity, emotional reaction, special significance, etc.), which may exaggerate similarities across groups of interest. Second, some features, such as the presence of multiple personified voices96, frequency, or the contents of visual hallucinations,81 are not represented. Third, these features might not be the best way of describing psychopathological phenomena as natural kinds, but may rather represent categories imposed by psychiatric convention.98 Our analysis focused on comparison studies involving 2 or more groups, which have generally adopted traditional approaches to symptom assessment. Other approaches that have used qualitative interviews and phenomenological approaches have revealed additional variables that do not figure in the above contrasts. It is possible that studies targeting variables such as changed aspects of self-consciousness, disturbed sense of internal space,99 bodily sensations,96 and thought-like properties of voices,96 may reveal hallucination features that are more discriminative of psychosis than those considered here. Furthermore, the present analysis might have had a different outcome if we had seeded our comparisons with a diagnostic group other than schizophrenia, such as Parkinson’s disease, where the features for comparison might have been significantly different. We could have also have adopted different criteria, such as comparison of hallucinations among 2 or more diagnostic groups without the requirement that one be schizophrenia. A final limitation is that the studies reviewed adopted widely varying measures and designs. Further progress in transdiagnostic comparison of hallucination features arguably requires consistency of measures across the groups studied.100

Finally, we consider implications for cognitive and neuroscientific models of hallucinations. We noted at the outset that there is very limited evidence in the cognitive and neuroscientific domains on which to base transdiagnostic comparisons of hallucinations. A further issue concerns the problem of mapping cognitive profiles of different groups to specific features of hallucinations, as opposed to their mere presence or absence. Mostly such research compares diagnostic groups with healthy controls or (increasingly) uses hallucination incidence as an independent variable within a particular diagnostic group: eg, comparing schizophrenia patients with and without hallucinations.

For these and other reasons, a discussion and comparison of cognitive and neurobiological models across diagnostic groups is beyond the scope of the present article. There are well-developed models of hallucinations in schizophrenia9,11,101,102 and in neurodegenerative disease such as Parkinson’s disease.103–105 A complication is that the models for these disorder groups are rather divergent, with some schizophrenia models proposing hyperactivity of the auditory cortex mediated by dopamine release and Parkinson’s models proposing underactivity of the occipital cortex mediated by acetylcholine. No such models have been developed for other conditions except for nonclinical hallucinations, which some continuum approaches propose can be best understood as variants of schizophrenia models. Given the many featural similarities of hallucinations among the disorders discussed here, further effort is needed in developing and integrating neurocognitive models across diagnostic groups.

Conclusions

Hallucinations are a feature of human experience that crosses diagnostic category boundaries and straddles the divide between psychopathological and nonclinical experience. They occur widely across diagnostic disorders and their presence or absence is only clinically useful when considered in conjunction with other symptoms and clinically relevant data. There are no “points of rarity” when we address the features of hallucinations in schizophrenia, with the possible exception of age of onset. We recommend that future studies systematically ask about onset, and the conditions and context in which hallucination first occurred.106,107 Other features may be particularly valuable in distinguishing other disorders, but more research is needed which pays attention to phenomenological and clinical features of hallucinations and compares them in methodologically robust designs across diagnostic groups and into the nonclinical population.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

Wellcome Trust (WT108720 to C.F.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Esquirol E. Mental Maladies; A Treatise on Insanity. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Blanchard; 1845. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berrios GE. The History of Mental Symptoms: Descriptive Psychopathology Since the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diefendorf AR, Kraepelin E. Clinical Psychiatry: A Textbook for Students and Physicians. Abstracted and adapted from the 7th German edition of Kraepelin’s Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie, new ed., rev. and augment. New York, NY: MacMillan; 1907. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schneider K. Clinical Psychopathology, trans. by Hamilton MW. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelleher I, Devlin N, Wigman JT, et al. Psychotic experiences in a mental health clinic sample: implications for suicidality, multimorbidity and functioning. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1615–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Os J, Reininghaus U. Psychosis as a transdiagnostic and extended phenotype in the general population. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:118–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Junginger J, Frame CL. Self-report of the frequency and phenomenology of verbal hallucinations. J Nerv Mental Dis. 1985;173:149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Waters F, Allen P, Aleman A, et al. Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia populations: a review and integrated model of cognitive mechanisms. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:683–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johns LC, Kompus K, Connell M, et al. Auditory verbal hallucinations in persons with and without a need for care. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(suppl 4):S255–S264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alderson-Day B, Diederen K, Fernyhough C, et al. Auditory hallucinations and the Brain’s resting-state networks: findings and methodological observations. Schizophr Bull. 2016. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbw078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Leede-Smith S, Barkus E. A comprehensive review of auditory verbal hallucinations: lifetime prevalence, correlates and mechanisms in healthy and clinical individuals. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brasic JR. Hallucinations. Percept Motor Skills. 1998;86:851–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keshavan MS, Kaneko Y. Secondary psychoses: an update. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:4–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stephane M, Starkstein S, Pahissa J. Psychosis in general medical and neurological conditions. In: Waters F, Stephane M, eds. The Assessment of Psychosis: A Reference Book and Rating Scales for Research and Practice. Chap. 13. 1st ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014:136–149. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eaton W, Romanoski A, Anthony JC, Nestadt G. Screening for psychosis in the general population with a self-report interview. J Nerv Mental Dis. 1991;179:689–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tien AY. Distributions of hallucinations in the population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1991;26:287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Linscott R, Van Os J. An updated and conservative systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence on psychotic experiences in children and adults: on the pathway from proneness to persistence to dimensional expression across mental disorders. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1133–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McGee R, Williams S, Poulton R. Hallucinations in nonpsychotic children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:12–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zayas EM, Grossberg GT. The treatment of psychosis in late life. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 1):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bexton WH, Heron W, Scott TH. Effects of decreased variation in the sensory environment. Can J Psychol. 1954;8:70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mason OJ, Brady F. The psychotomimetic effects of short-term sensory deprivation. J Nerv Mental Dis. 2009;197:783–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith MJ, Thirthalli J, Abdallah AB, Murray RM, Cottler LB. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in substance users: a comparison across substances. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mosholder AD, Gelperin K, Hammad TA, Phelan K, Johann-Liang R. Hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms associated with the use of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drugs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lebain P, Juliard C, Davy J, Dollfus S. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in preventive antimalarial treatment with mefloquine: apropos of 2 cases. L’Encephale. 1999;26:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hammeke TA, McQuillen MP, Cohen BA. Musical hallucinations associated with acquired deafness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983;46:570–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. ffytche DH. Visual hallucinations in eye disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davis AT. Psychotic states associated with disorders of thyroid function. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1990;19:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alink J, de Vries TW. Unexplained seizures, confusion or hallucinations: think Hashimoto encephalopathy. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:451–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, Rao MG, Varambally S, Gangadhar BN. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25:E34–E35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stumpf WE, Privette TH. Light, vitamin D and psychiatry. Psychopharmacology. 1989;97:285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vogels A, Hert MD, Descheemaeker M, et al. Psychotic disorders in Prader–Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;127:238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kayser MS, Dalmau J. The emerging link between autoimmune disorders and neuropsychiatric disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23:90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. De Ronchi D, Bellini F, Cremante G, et al. Psychopathology of first-episode psychosis in HIV-positive persons in comparison to first-episode schizophrenia: a neglected issue. AIDS Care. 2006;18:872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fortuyn HAD, Lappenschaar G, Nienhuis FJ, et al. Psychotic symptoms in narcolepsy: phenomenology and a comparison with schizophrenia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Teeple RC, Caplan JP, Stern TA. Visual hallucinations: differential diagnosis and treatment. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11:26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Madhusoodanan S, Danan D, Brenner R, Bogunovic O. Brain tumor and psychiatric manifestations: a case report and brief review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16:111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sachdev P, Smith J, Cathcart S. Schizophrenia-like psychosis following traumatic brain injury: a chart-based descriptive and case–control study. Psychol Med. 2001;31:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trimble M, Kanner A, Schmitz B. Postictal psychosis. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19:159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fenelon G. Hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. In: Laroi F, Aleman A, eds. Hallucinations: A Guide to Treatment and Management. Chap. 19. 1st ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010:351–376. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sanchez-Castaneda C, Rene R, Ramirez-Ruiz B, et al. Frontal and associative visual areas related to visual hallucinations in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Mov Disord. 2010;25:615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baethge C, Baldessarini R, Freudenthal K, Streeruwitz A. Hallucinations in bipolar disorder: characteristics and comparison to unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Miotto P, Pollini B, Restaneo A, et al. Symptoms of psychosis in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Honig A, Romme MAJ, Ensink BJ, Escher SD, Pennings MHA, Devries MW. Auditory hallucinations: a comparison between patients and nonpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Daalman K, Boks MP, Diederen KM, et al. The same or different? A phenomenological comparison of auditory verbal hallucinations in healthy and psychotic individuals. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lindal E, Stefansson G, Stefansson S. The qualitative difference of visions and visual hallucinations: a comparison of a general-population sample and clinical sample. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35:405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Peters E, Ward T, Jackson M, et al. Clinical, socio-demographic and psychological characteristics in individuals with persistent psychotic experiences with and without a “need for care”. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leudar I, Thomas P, McNally D, Glinski A. What voices can do with words: pragmatics of verbal hallucinations. Psychol Med. 1997;27:885–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cottam S, Paul S, Doughty O, Carpenter L, Al-Mousawi A, Karvounis S, Done D. Does religious belief enable positive interpretation of auditory hallucinations? A comparison of religious voice hearers with and without psychosis. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2011;16:403–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Davies MF, Griffin M, Vice S. Affective reactions to auditory hallucinations in psychotic, evangelical and control groups. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alpert M, Silvers KN. Perceptual characteristics distinguishing auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia and acute alcoholic psychoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1970;127:298–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bell D. Comparison of amphetamine psychosis and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1965;111:701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Goodwin D, Alderson P, Rosenthal R. Clinical significance of hallucinations in psychiatric disorders: a study of 116 hallucinatory patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;24:76–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Malitz S, Wilkens B, Esecover H. A comparison of drug-induced hallucinations with those seen in spontaneously occurring psychosis. In: West LJ, ed. Hallucinations. Chap 5. 1st ed. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1962:50–63. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mitchell J, Vierkant AD. Delusions and hallucinations of cocaine abusers and paranoid schizophrenics: a comparative study. J Psychol. 1991;125:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mott RH, Iver FS, Anderson JM. Comparative study of hallucinations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Núñez L, Gurpegui M. Cannabis-induced psychosis: a cross-sectional comparison with acute schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:812–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Young BG. A phenomenological comparison of LSD and schizophrenic states. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;124:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Aggernaes A. The experienced reality of hallucinations and other psychological phenomena. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1972;48:220–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Johns LC, Hemsley D, Kuipers E. A comparison of auditory hallucinations in a psychiatric and nonpsychiatric group. Br J Clin Psychol. 2002;41:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Perez M, Trimble M, Murray N, Reider I. Epileptic psychosis: an evaluation of PSE profiles. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;146:155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Slater E, Beard A. The schizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy. Br J Psychiatry. 1963;109:95–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cutting J. The phenomenology of acute organic psychosis. Comparison with acute schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Frieske DA, Wilson WP. Formal qualities of hallucinations: a comparative study of the visual hallucinations in patients with schizophrenic, organic, and affective psychoses. Proc Annu Meet Am Psychopathol Assoc. 1966;54:49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Johnstone EC, Cooling N, Frith CD, Crow T, Owens D. Phenomenology of organic and functional psychoses and the overlap between them. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;153:770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lowe GR. The phenomenology of hallucinations as an aid to differential diagnosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bowman K, Raymond A. A statistical study of hallucinations in the manic-depressive psychoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1931;88:299–309. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chaturvedi SK, Sinha VK. Recurrence of hallucinations in consecutive episodes of schizophrenia and affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 1990;3:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Okulate GT, Jones OB. Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenic and affective disorder Nigerian patients: phenomenological comparison. Transcult Psychiatry. 2003;40:531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shinn AK, Pfaff D, Young S, Lewandowski KE, Cohen BM, Öngür D. Auditory hallucinations in a cross-diagnostic sample of psychotic disorder patients: a descriptive, cross-sectional study. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hepworth CR, Ashcroft K, Kingdon D. Auditory hallucinations: a comparison of beliefs about voices in individuals with schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2013;20:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kingdon DG, Ashcroft K, Bhandari B, et al. Schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder: similarities and differences in the experience of auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and childhood trauma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Slotema CW, Daalman K, Blom JD, Diederen KM, Hoek HW, Sommer IE. Auditory verbal hallucinations in patients with borderline personality disorder are similar to those in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1873–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tschoeke S, Steinert T, Flammer E, Uhlmann C. Similarities and differences in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia with voice hearing. J Nerv Mental Dis. 2014;202:544–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hamner MB, Frueh BC, Ulmer HG, et al. Psychotic features in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and schizophrenia: comparative severity. J Nerv Mental Dis. 2000;188:217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jessop M, Scott J, Nurcombe B. Hallucinations in adolescent inpatients with post-traumatic stress disorder and schizophrenia: similarities and differences. Australas Psychiatry. 2008;16:268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dorahy MJ, Shannon C, Seagar L, et al. Auditory hallucinations in dissociative identity disorder and schizophrenia with and without a childhood trauma history: similarities and differences. J Nerv Mental Dis. 2009;3:892–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Eagles JM, Wilson AM, Hunter D, Callender JS. A comparison of anorexia nervosa and affective psychosis in young females. Psychol Med. 1990;20:119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kimhy D, Corcoran C, Harkavy-Friedman JM, et al. Visual form perception: a comparison of individuals at high risk for psychosis, recent onset schizophrenia and chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;97:25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Brett C, Peters E, McGuire P. Which psychotic experiences are associated with a need for clinical care? Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:648–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Waters F, Collerton D, Blom JD, et al. Visual hallucinations in the psychosis-spectrum, and comparative information from neurodegenerative disorders and eye disease. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(suppl 4):S233–S245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Nayani TH, David AS. The auditory hallucination: a phenomenological survey. Psychol Med. 1996;26:177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Toone BK, Garralda ME, Ron MA. The psychoses of epilepsy and the functional psychoses: a clinical and phenomenological comparison. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Standage K. Schizophreniform psychosis among epileptics in a mental hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:231–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Dell’Osso L, Akiskal HS, Freer P, Barberi M, Placidi GF, Cassano GB. Psychotic and nonpsychotic bipolar mixed states: comparisons with manic and schizoaffective disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;243:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Larøi F, Sommer IE, Blom JD, et al. The characteristic features of auditory verbal hallucinations in clinical and nonclinical groups: state-of-the-art overview and future directions. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:724–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Oulis PG, Mavreas VG, Mamounas JM, Stefanis CN. Clinical characteristics of auditory hallucinations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;92:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bliss EL, Clark LD. Visual hallucinations. In: West LJ, ed. Hallucinations. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1962:92–108. [Google Scholar]

- 89. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed., revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Perez M, Trimble MR. Epileptic psychosis—diagnostic comparison with process schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;137:245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Close H, Garety P. Cognitive assessment of voices: further developments in understanding the emotional impact of voices. Br J Clin Psychol. 1998;37:173–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Heriot-Maitland C, Knight M, Peters E. A qualitative comparison of psychotic-like phenomena in clinical and non-clinical populations. Br J Clin Psychol. 2012;51:37–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Björk C, et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373:234–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:383–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Motooka H, Ueki H, Ishida S, Maeda H. Ictal visual hallucination intermittent photic stimulation: using evaluation of the clinical findings, ictal EEG, ictal SPECT, and rCBF. No to Shinkei. 1999;51:791–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Woods A, Jones N, Alderson-Day B, Callard F, Fernyhough C. Experiences of hearing voices: analysis of a novel phenomenological survey. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Wigman JT, de Vos S, Wichers M, van Os J, Bartels-Velthuis AA. A transdiagnostic network approach to psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2016. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbw095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kendell RE. The Role of Diagnosis in Psychiatry. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Henriksen MG, Raballo A, Parnas J. The pathogenesis of auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: a clinical–phenomenological account. Philos Psychiatry Psychol. 2015;22:165–181. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kelleher I. Auditory hallucinations in the population: what do they mean and what should we do about them? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Allen P, Modinos G, Hubl D, et al. Neuroimaging auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: from neuroanatomy to neurochemistry and beyond. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Garety PA, Bebbington P, Fowler D, Freeman D, Kuipers E. Implications for neurobiological research of cognitive models of psychosis: a theoretical paper. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1377–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Collerton D, Perry E, McKeith I. Why people see things that are not there: a novel Perception and Attention Deficit model for recurrent complex visual hallucinations. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28:737–757; discussion 757–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Diederich NJ, Fénelon G, Stebbins G, Goetz CG. Hallucinations in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Howard R, Brammer M, David A, Woodruff P, Williams S. The anatomy of conscious vision: an fMRI study of visual hallucinations. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:738–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Carter DM, Mackinnon A, Howard S, Zeegers T, Copolov DL. The development and reliability of the Mental Health Research Institute Unusual Perceptions Schedule (MUPS): an instrument to record auditory hallucinatory experience. Schizophr Res. 1995;16:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Escher S, Hage P, Romme M, Romme M. Maastricht Interview With a Voice Hearer. Understanding Voices: Coping With Auditory Hallucinations and Confusing Realities. Gloucester, UK: Handsell; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.