Abstract

We investigated the functional consequences following deletion of a microRNA (miR) termed miR-595 which resides on chromosome 7q and is localised within one of the commonly deleted regions identified for Myelodysplasia (MDS) with monosomy 7 (−7)/isolated loss of 7q (7q-). We identified several targets for miR-595, including a large ribosomal subunit protein RPL27A. RPL27A downregulation induced p53 activation, apoptosis and inhibited proliferation. Moreover, p53-independent effects were additionally identified secondary to a reduction in the ribosome subunit 60s. We confirmed that RPL27A plays a pivotal role in the maintenance of nucleolar integrity and ribosomal synthesis/maturation. Of note, RPL27A overexpression, despite showing no significant effects on p53 mRNA levels, did in fact enhance cellular proliferation. In normal CD34+ cells, RPL27A knockdown preferentially blocked erythroid proliferation and differentiation. Lastly, we show that miR-595 expression appears significantly downregulated in the majority of primary samples derived from MDS patients with (−7)/(7q-), in association with RPL27A upregulation. This significant downregulation of miR-595 is also apparent when higher risk MDS cases are compared to lower risk cases. The potential clinical importance of these findings requires further validation.

Keywords: myelodysplasia, ribosome, microRNA, haemopoiesis, chromosome

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short non-coding RNAs which play pivotal roles in a diverse range of cellular processes [1]. As current miRNA target identification assays are often associated with a lack of sensitivity and specificity, this led to our development of a novel assay to identify potential miRNA targets [2]. This assay relies upon functional activity rather than depending solely on computational algorithms addressing homology or binding to a putative target [3–5]. Furthermore, this methodology can aid identification of targets that are downregulated by mRNA cleavage or translation inhibition.

We focused on miRNAs localised to chromosome 7, in particular miR-595 at 7q36.3. This miRNA is localised within one of the commonly deleted regions (CDR) identified for MDS with monosomy 7 (−7)/isolated loss of 7q (7q-) [6–9]. We show, for the first time, that RPL27A, encoding a ribosomal subunit protein, is a target for miR-595.

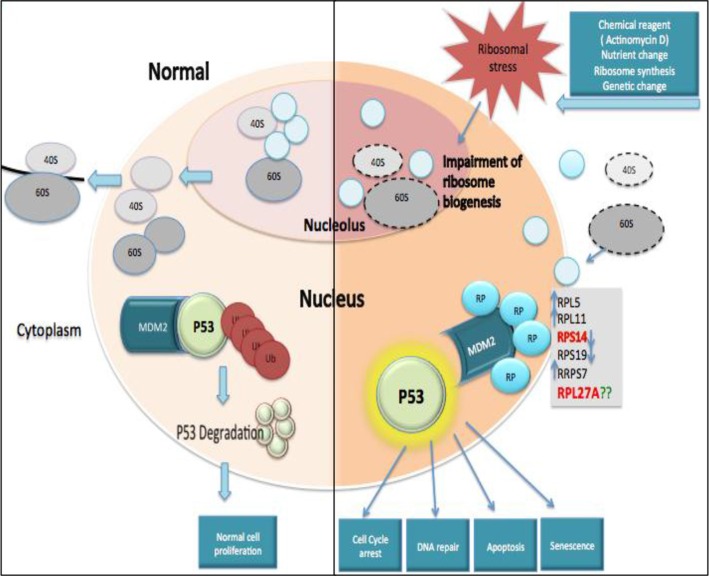

It is well established that impaired ribosome biogenesis can induce nuclear stress. This phenomenon can be associated with the development of clinical entities collectively known as “ribosomopathies” which include several congenital disorders and bone marrow failure syndromes, such as Diamond Blackfan Anaemia (DBA), Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS), Dyskeratosis Congentia (DC) and Cartilage-Hair Hypoplasia (CHH) syndrome, in addition to the acquired MDS subtype ‘5q- syndrome’ [10, 11]. More recently, it has also been recognised that ribosomal stress can induce p53 accumulation, although the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain complex (Figure 1). Marechal et al. were the first to demonstrate the complex interaction between RPL5, p53 and MDM2 [12]. Further studies have demonstrated that reduced expression of a range of ribosomal proteins, including RPS6, RPL22, RPL24, RPS19, RPS14 and RPL23, can all increase p53 levels whereas reductions in RPL11 and RPL5 actually decrease p53 levels [13–20]. In contrast, the overexpression of RPL5, RPL26 and RPL11 and other ribosomal proteins, induced p53 expression [19–23]. Uniquely, both reductions and overexpression of RPL23 and RPS14 augment p53 expression, highlighting the complex interaction of these ribosomal proteins and the p53 axis [18–24]. In this study, we focused on validating RPL27A as a novel target of miR-595. We investigated the effects of RPL27A knockdown on p53 activation, ribosome synthesis and maturation. Lastly, we investigated the expression of miR-595 in a cohort of patients with MDS.

Figure 1. Ribosomal protein-MDM2-p53 interactions.

Under steady state conditions, ribosome biogenesis occurs within the nucleolus and ribosome subunits are subsequently exported to the cytoplasm to facilitate formation of mature ribosomes and initiation of mRNA translation. MDM2 can mediate attachment of ubiquitin (Ub) molecules to p53, inducing p53 degradation and permitting normal cell proliferation. In contrast, ribosomal stress can impair ribosome biogenesis and disrupt ribosome assembly. This causes a release of free ribosomal proteins (RP), which interact with MDM2 and block its interaction with p53, resulting in p53 accumulation. Subsequently, activated p53 may cause cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, deregulated DNA repair or senescence.

RESULTS

Identification and validation of RPL27A as a target of miR-595

Our novel assay is based on the directional cloning of a 3′UTR cDNA target ID library (Sigma, MREH01) derived from 10 different human tissues and 10 human cell lines, representing 16,923 unique genes, cloned downstream of a TKzeo fusion gene in plasmid p3′TKzeo conferring zeocin resistance and Ganciclovir sensitivity. The breast carcinoma MCF7 cell line, lacking miR-595, was hence transfected with this cDNA library and underwent zeocin selection. Expanded zeocin resistant cells underwent infection with either a pBabePuro vector expressing miR-595 or empty vector. After 48 hours, cells underwent puromycin selection and subsequent ganciclovir (GCV) counter-selection. Surviving colonies were expanded, genomic DNA isolated and PCR amplified using vector specific primers. Supplementary Figure S1 displays one such amplification. Candidate amplicon bands were present in multiple independent samples and hence represented putative miR-595 targets. These bands of interest underwent purification and sequencing. A BLAST sequence search displayed a high degree of homology for two different transcripts; ribosomal protein L27A (RPL27A; 500 bp) and heat shock protein 14 (HSPA14; 800 bp). We focused on validation of RPL27A as a target for miR-595 and establishing the biological function of RPL27A.

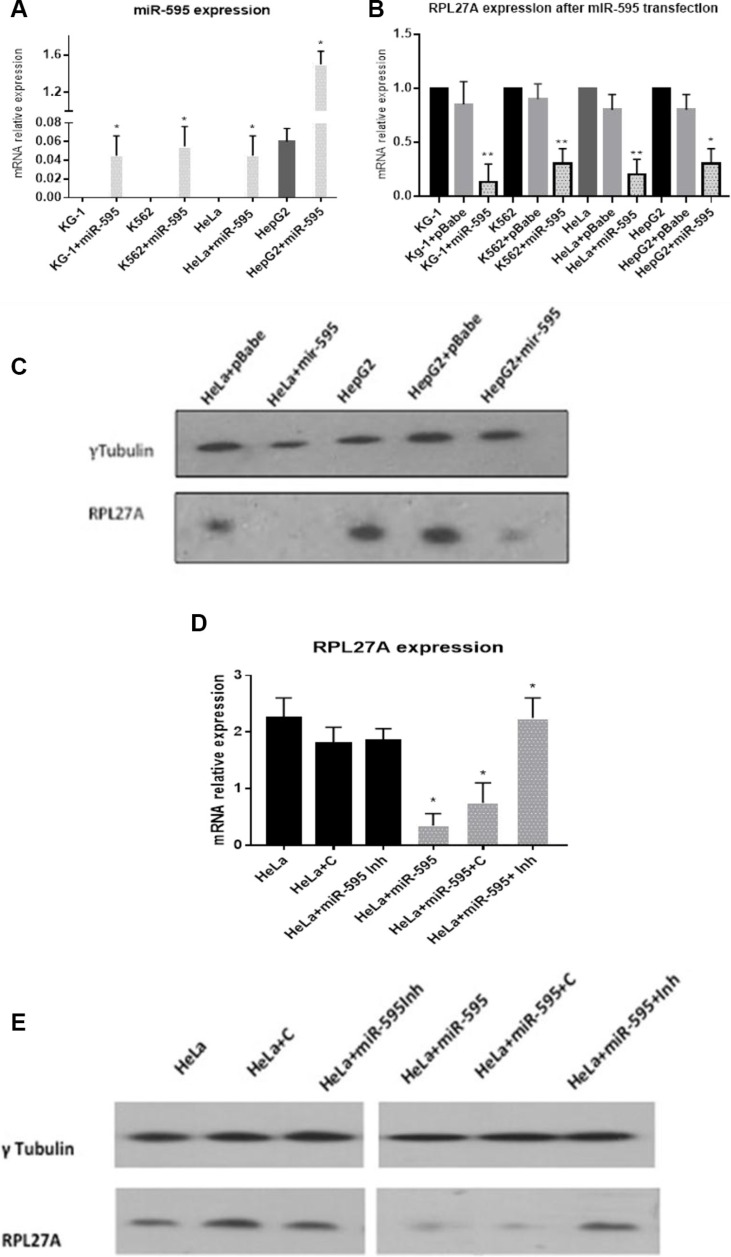

Validation experiments were performed in the HeLa, HepG2, KG-1 and K562 cell lines. Each underwent transfection with either pBabepuro-miR-595 or empty vector followed by puromycin selection. Cells were screened for miR-595 expression by quantitative – Reverse Transcriptase PCR (qPCR) and demonstrated significantly increased miR-595 expression compared to wild-type (Figure 2A). Following miR-595 overexpression, RPL27A mRNA levels were decreased by 83% in KG-1 cells, 73% in K562 cells, 88% in HeLa cells and 55% in HepG2 cells respectively compared to controls (Figure 2B). RPL27A protein levels in both HeLa and HepG2 cells were also downregulated (Figure 2C). Lastly, HeLa wild-type cells and miR-595-transfected HeLa cells underwent additional transfection with a hairpin inhibitor directed against miR-595 (Miridian) and a control hairpin inhibitor (Dharmacon) and analysed for RPL27A mRNA and protein expression (Figure 2D). Wild-type HeLa cells showed no significant alteration in RPL27Aexpression levels following inhibitor transfection, whereas HeLa cells transfected with miR-595 showed reduced expression of RPL27A. This reduced RPL27A expression could be reversed with the miR-595 hairpin inhibitor (Miridian), resulting in a 4-5-fold upregulation of RPL27A mRNA transcripts and protein expression.

Figure 2. Validation of RPL27A as a target for miR-595 by qRT-PCR and western blot analysis.

Endogenous RPL27A mRNA and protein levels were determined in untransfected, pBabePuro empty vector (pBabe), and pBabePuro-miR-595 (miR-595) transfected cells. miR-595 expression levels were determined in untransfected and miR-595 transfected KG-1. K562, HeLa and HepG2 cells 48 hrs after the miRNA transfection (A). To investigate if miR-595 overexpression downregulates RPL27A expression, RPL27A mRNA was quantified by qRT-PCR in untransfected cells, cells transfected with empty vector and cells transfected with miR-595. Downregulated expression of RPL27A occurred in all cell lines overexpressing miR-595, in contrast to cells transfected with pBabe empty vector and untransfected cells. Results represent three independent experiments; bars display the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (B). HeLa and HepG2 cells were transfected with empty vector or miR-595. RPL27A protein expression is downregulated in HeLa and HepG2 cells expressing miR-595 compared to control. Tubulin was used as a loading control (C). HeLa cells which did not express miR-595 were transfected with either hairpin control inhibitor (HeLa+C) or miR-595 inhibitor (HeLa+ miR-595Inh). HeLa cells expressing miR-595 were also transfected with hairpin control or miR-595 inhibitor. Upregulated RPL27A mRNA and protein expression was evident in miR-595 expressing HeLa cells which underwent transfection with the miR-595 inhibitor compared to controls (D, E).

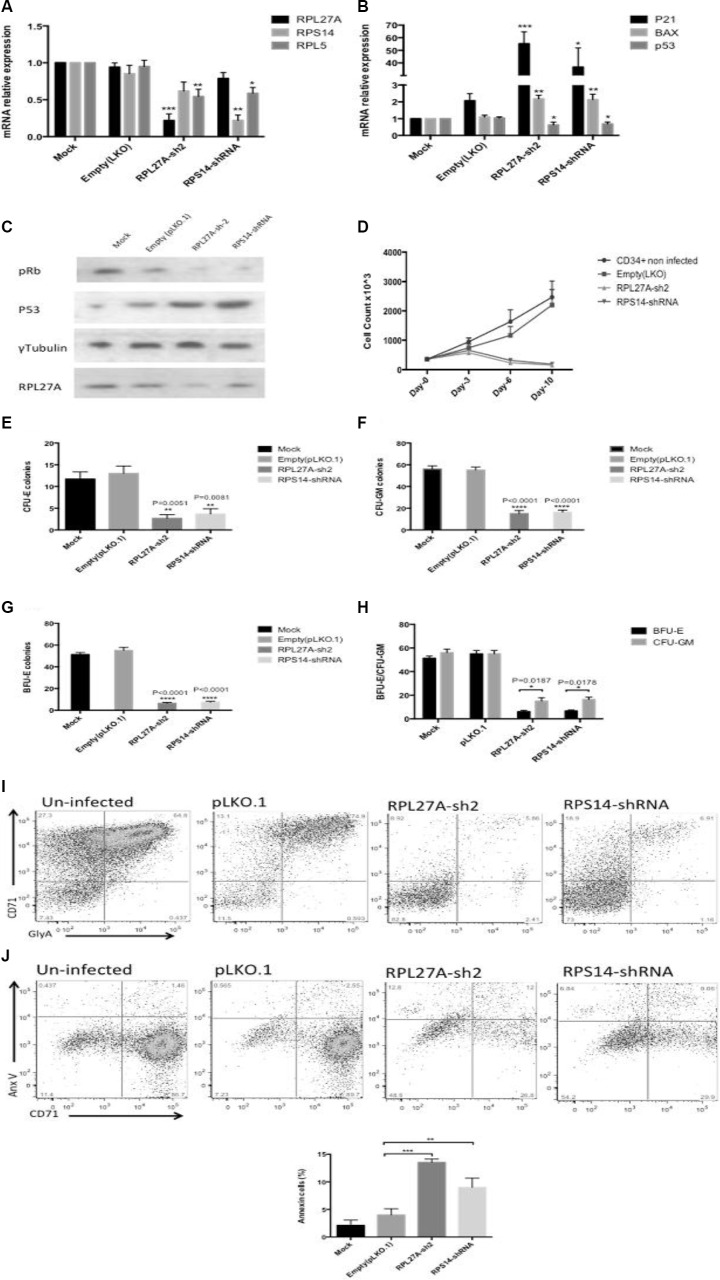

Decreased expression of RPL27A causes p53 activation

We examined the effects of reduced RPL27A expression in HCT-116, HCT-116-p53−/−, K562 and HEL cell lines and compared these to the already well-established effects induced by RPS14 and RPL5 downregulation. Two different lentivirus short-hairpin (sh) RNAs were chosen, RPL27A-sh2 and RPL27A-sh4, which decreased expression by 80% and 40% respectively at mRNA and protein levels. Efficient knockdown of both RPS14 and RPL5 via lentiviral shRNA was also achieved (Supplementary Figure S2A–S2D).

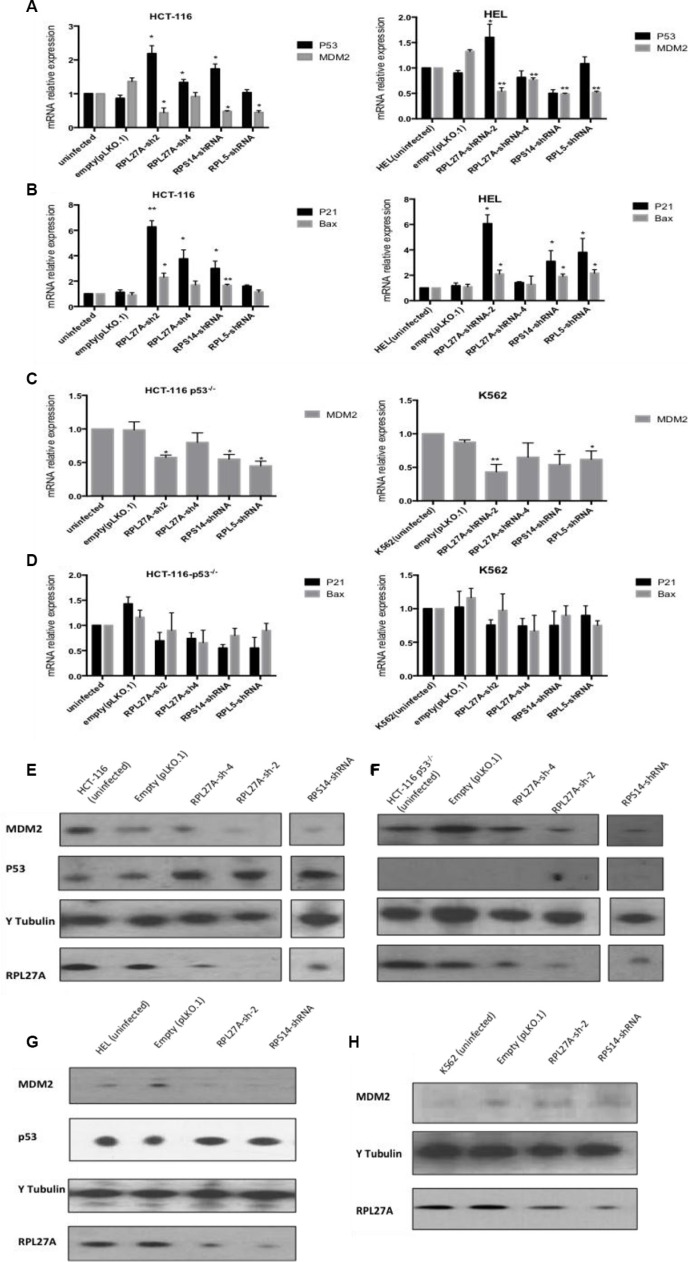

In the p53-expressing HCT-116 cell line, RPL27A-sh2 and -sh4 mediated knockdown resulted in a significant increase in p53 mRNA levels compared to control (p = 0.005 and p = 0.021 respectively). For the p53 expressing HEL cells, an increase in p53 expression was only observed following RPL27A-sh2 (p = 0.027), RPS14 knockdown resulted in significant p53 upregulation (p = 0.0149) whereas RPL5 depletion did not induce any significant changes (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Decreased expression of RPL27A activates the p53 pathway.

HCT-116 and HEL cell lines dually express MDM2 and p53 mRNA. RPL27A and RPS14 depletion significantly augmented expression of p53 mRNA in HCT-116 cells compared to controls. RPL27A-sh2RNA, RPS14-shRNA and RPL5-shRNA reduced MDM2 expression in both cell lines (A). Increased expression of the p53 target genes p21 and Bax was induced by RPL27A and RPS14 depletion in HCT-116 and HEL cells (B). In the HCT116 p53−/− and K562 cell lines, MDM2 expression was reduced following RPL27A-shRNA2, RPS14-shRNA and RPL5-shRNA infection but no significant effects were noted for p21 or Bax expression. Bars display the mean results from three independent experiments ± SEM (p values were determined using two tail student t-test *p = < 0.05; **p = < 0.005)) (C, D). Protein expression of p53, MDM2 and RPL27A was determined following RPL27A-sh2 or RPS14-shRNA mediated knockdown. Tubulin was used as a loading control. In the HCT-116 and cell lines, depletion of RPL27A and RPS14 induced p53 expression and reduced MDM2 (E, G). In the HCT-116 p53−/− cell line, depletion of RPL27A and RPS14 reduced MDM2 expression (F). No significant reduction in MDM2 protein expression was identified compared to empty vector following infection with either RPL27A shRNA and RPS14 shRNA in K562 cells (H). In all cell lines, infection with RPS14 shRNA, caused a reduction in RPL27A expression. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

MDM2 is a pivotal feedback regulator of the p53 pathway. Depletion of RPL27A, RPS14 and RPL5 resulted in reduced MDM2 expression at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level in all cell lines except in K562 cells, where RPL27A-sh2 induced significant reductions at mRNA level only (Figure 3A and 3C). Co-immunoprecipitation assays demonstrated that endogenous RPL27A interacts with endogenous MDM2 and RPL5 in HCT-116 cells (Supplementary Figure S3).

To investigate if induction of p53 expression resulted in transcriptional activation, expression of the p53 targets p21 and Bax was determined. In HCT-116 cells, both p21 and Bax mRNA levels were significantly increased following both RPL27A-shRNA and RPS14-shRNA-mediated downregulation. In contrast, RPL5 knockdown did not induce significant changes. In HEL cells, RPL27A-sh2, RPS14 shRNA and RPL5 shRNA induced significant increases in both bax and p21 expression. As expected, for the null p53 cell lines, no changes in p21 and Bax expression were identified, indicating that p21 and Bax induction occurred in a p53-dependent fashion (Figure 3B and 3D). Both RPL27A-sh2 and RPS14 shRNA, compared to controls, increased p53 protein expression in HCT-116 and HEL cells. Interestingly, knockdown of RPS14 also resulted in a decreased expression of RPL27A (Figure 3E). Of note, RPL27A overexpression in HCT-116 cells showed no significant effect on p53 mRNA levels or alteration in the cell cycle profile but did induce proliferation (Supplementary Figure S4A–S4D).

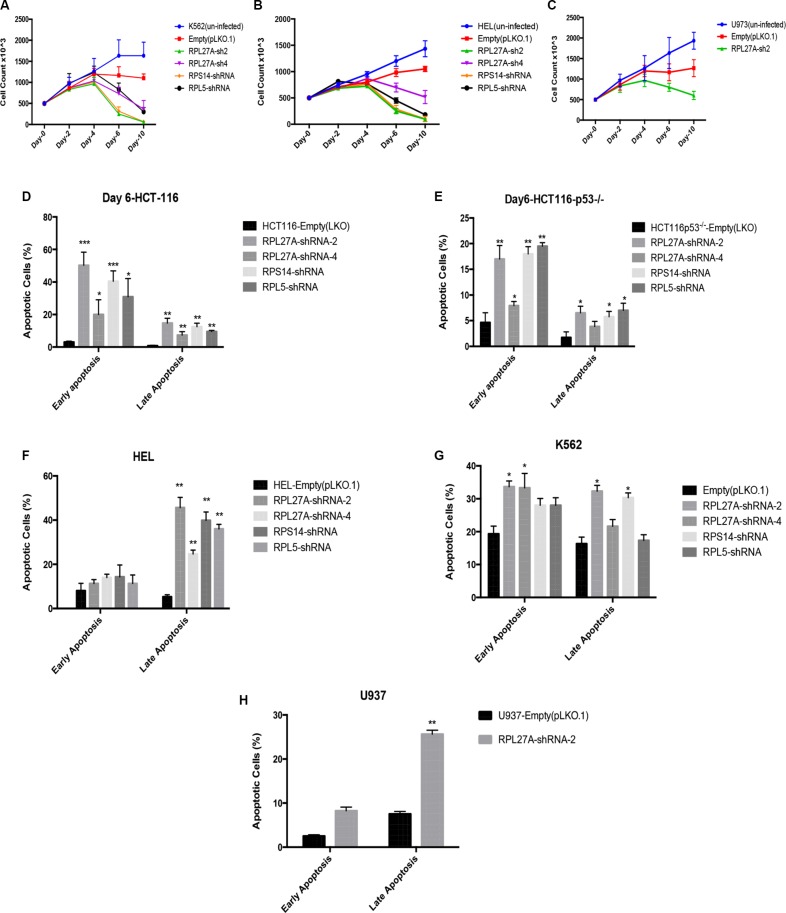

Decreased expression of RPL27A induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation in a p53 independent manner

Initially, proliferation assays were performed in both p53-expressing and p53-null cells to determine effects of RPL27A depletion (Figure 4A–4B). In both K562 and HEL cells, a significant reduction in cell numbers was detected by day 4, and increased over time, following RPL27A knockdown by RPL27A-sh2. This was also the case for RPS14 and RPL5 knockdown. RPL27A-sh4 infection, however, displayed less effect on cell numbers. Unexpectedly, we did not observe significant differences in cell death between p53 expressing HEL cells and p53 null K562 cells. To establish if this was truly a p53-independent effect, we repeated knockdown experiments with RPL27A-sh2 in the p53 null cell line U937. Again we noted a decrease in cell numbers compared to control, although this was not lethal (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Reduction in RPL27A decreases cell proliferation and induces apoptosis.

Proliferation was assessed by cell enumeration at 48-hour intervals. Significant reductions in K562 and HEL cells were determined by day 4 post-infection with RPL27A-sh2, RPL27A-sh4, RPS14 shRNA and RPL5-shRNA compared to controls (A, B). Although attenuated proliferation was also noted in the U937 cells following RPL27A-sh2, this was less marked than in the other cell lines examined (C). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Apoptosis was assessed via flow cytometric assessment of Annexin V and 7-ADD expression in HCT-116, HCT-116 p53−/−, K562 and HEL cells at day 6 following infection with empty vector, both RPL27A shRNAs, RPS14 shRNA and RPL5 shRNA. Compared to controls, RPL27A depletion induced significant apoptosis in all 4 cell lines (D–G). Similarly, knockdown of RPS14 and RPL5 induced significant apoptosis. In the U937 cell line, compared to empty vector, RPL27A-sh2 infection significantly increased the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis but to a lesser degree than observed in the other cell lines (H). Columns display the mean results from three independent experiments ± SEM (*p = < 0.05; **p = < 0.005)).

Apoptosis assays using Annexin-V/7-AAD staining at Day 6 following shRNA infection were performed (Figure 4D–4H). HCT-116 infection with RPL27A-sh2 induced significant increases in cells at the early stage of apoptosis (55%), as was the case with RPS14 (40%) and RPL5 (35%) knockdown. Of note, RPL27A-sh4, which induces < 50% RPL27A knockdown, only led to a 25% increase in apoptotic cells. The HCT-116-p53−/− cell line also displayed significant increases in early (range 15–20%) and late stages of apoptosis (8–10%). For HEL cells, a significant increase in the late stage of apoptosis was observed for all shRNAs (40–50%). However, in p53 null K562 cells, depletion of RPL27A and RPS14 led to an increase in apoptotic cells by an average of 15–20% at both early and late stages. Lastly, U937 cells demonstrated a significant, but less marked, induction in apoptosis following RPL27A-sh2 infection.

RPL27A deficiency induces a reduction in ribosomal 60S and causes nucleolar disruption

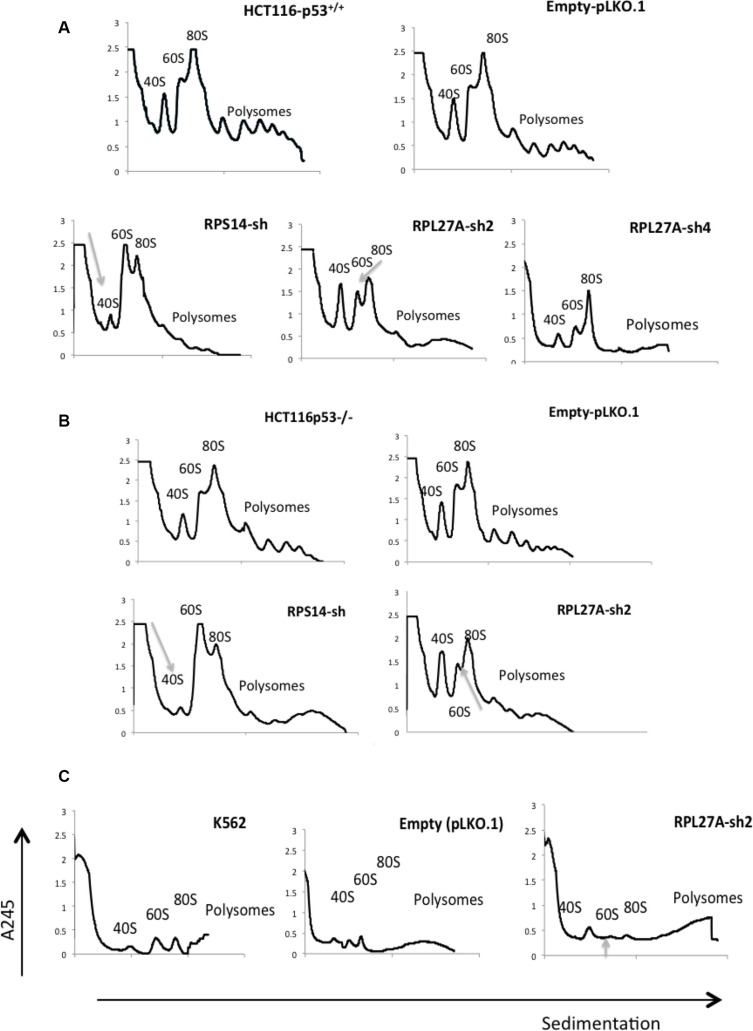

Polysome profiling was performed to establish if RPL27A deficiency induced ribosomal defects. Profiling was performed in HCT-116, HCT-116-p53−/− and K562 cells infected with empty vector, RPL27A-sh2 or RPS14 shRNA respectively. Downregulation of RPL27A resulted in a reduction of the 60S subunit and slight increase in the 40S subunit in all three-cell lines (Figure 5). Of note, RPL27A-sh4 was examined in HCT-116 cells where it induced a slight reduction in the 60S subunit only.

Figure 5. Depletion of RPL27A causes defects in 60S subunit maturation.

Polysome profiling, utilising sucrose gradient fractionation, was performed in cells post infection with lentivirus-expressing RPL27A shRNAs, RPS14 shRNA and empty vector pLKO.1 respectively. Polysomes were detected at A245 wavelength using a UV monitor at day 6 post infection and ribosomal native subunits 40S, 60S and 80S are indicated. In HCT-116 and HCT-116 p53−/− cells, RPL27A depletion induced a significant reduction in the 60S subunit relative to control. As predicted, RPS14 shRNA reduced the 40S subunit compared to the relative control (A, B). RPL27A shRNA also reduced the 60S subunit in the K562 cell line (C). Results are representative of duplicate experiments. HCT-116 cell controls, post-infection with pLKO.1 empty vector or the ribosomal protein directed shRNAs as indicated, were fixed on slides and stained with an anti-fibrillarin antibody (green: nucleolar marker) on day 6. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). Slides were analysed using a 40× objective Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope and ZEN 2010 software. Results are representative of duplicate experiments. Disruption of nucleolar fibrillarin staining was evident in cells infected with shRNAs targeting the ribosomal proteins as indicated when compared to pLKO.1 empty vector (D).

Next, nucleolar staining was performed. HCT-116 and HCT-116 p53−/− cells were infected with empty vector, RPL27A-sh2, RPS14-shRNA or RPL5-shRNA, underwent puromycin selection and subsequently were collected, fixed and stained with anti-fibrillarin antibody. Depletion of RPL27A, RPS14 and RPL5 resulted in abnormal dispersion of fibrillarin in the nucleolus (Figure 5). These characteristics may in part explain the p53-independent effects observed following RPL27A depletion.

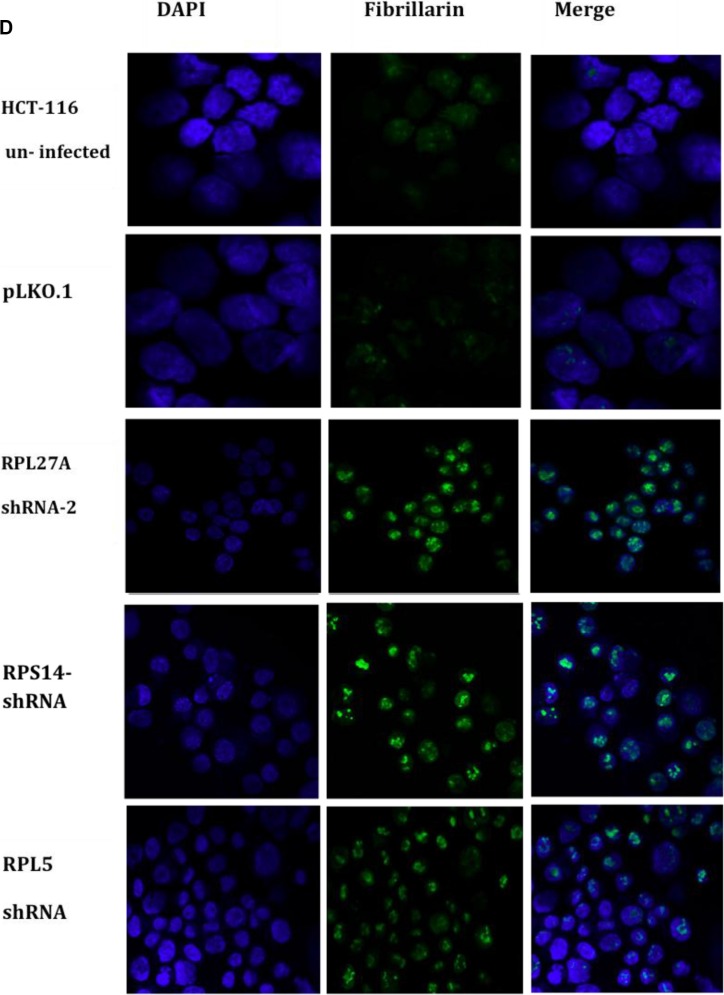

RPL27A depletion induces early p53 dependent effects

To investigate time-dependent effects following RPL27A depletion, we collected samples for analysis from HCT-116 and HCT-116 p53−/− cells at 48 hours post-infection with RPL27A-sh2, RPS14 shRNA, RPL5 shRNA or control. RPL27A-sh2, RPS14 shRNA and RPL5 shRNA infection induced p53-dependent apoptosis. In contrast, no significant increase in apoptosis was observed in the p53 null cell line at this early time point (Figure 6A). Furthermore, MTT assays demonstrated reduced HCT-116 cell viability following both RPL27A and RPS14 depletion. In contrast, RPL5 depletion did not affect cell viability in either cell line (Figure 6B). Polysome profiling was performed on HCT-116 cells following RPL27A-sh2 infection (Figure 6C). Although RPL27A depletion reduced the 60S subunit, this was less marked than the later reduction observed on Day 6, suggesting that attenuation of the 60s subunit increases with time.

Figure 6. RPL27A deficiency results in early p53-dependent apoptotic defects.

HCT-116 and HCT-116 p53−/− cells were infected with control empty vector or shRNAs directed against RPL27A, RPS14 and RPL5 respectively and collected for analysis at 48-hours post infection. For flow cytometric analysis, cells were stained with Annexin and 7-AAD. Cells in the upper left quadrant indicate Annexin positive, early apoptotic cells. Cells in the upper right quadrant indicate Annexin-positive/7-AAD-positive, late apoptotic cells. Compared to empty vector, RPL27A-sh2, RPS14 shRNA and RPL5 shRNA significantly induced apoptosis in the p53 containing HCT-116 cells only (A). Column diagrams represent mean % of apoptotic cells from three independent experiments ± SEM. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.005). MTT assays were performed to delineate effects on cell viability (B). A significant reduction in cell viability was evident following RPL27A-sh2, -sh4 and RPS14 shRNA in HCT-116 cells only and not in the HCT-116 −/− cell line. Results are expressed as relative fold change mean ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.005). Polysome profiling (using sucrose gradient fractionation) was performed in HCT-116 cells infected with either RPL27A-sh2 or empty vector only. Polysomes were detected at A245 using an ultraviolet monitor. RPL27A depletion reduced the 60S subunit compared with relevant controls; experiments performed in duplicate (C).

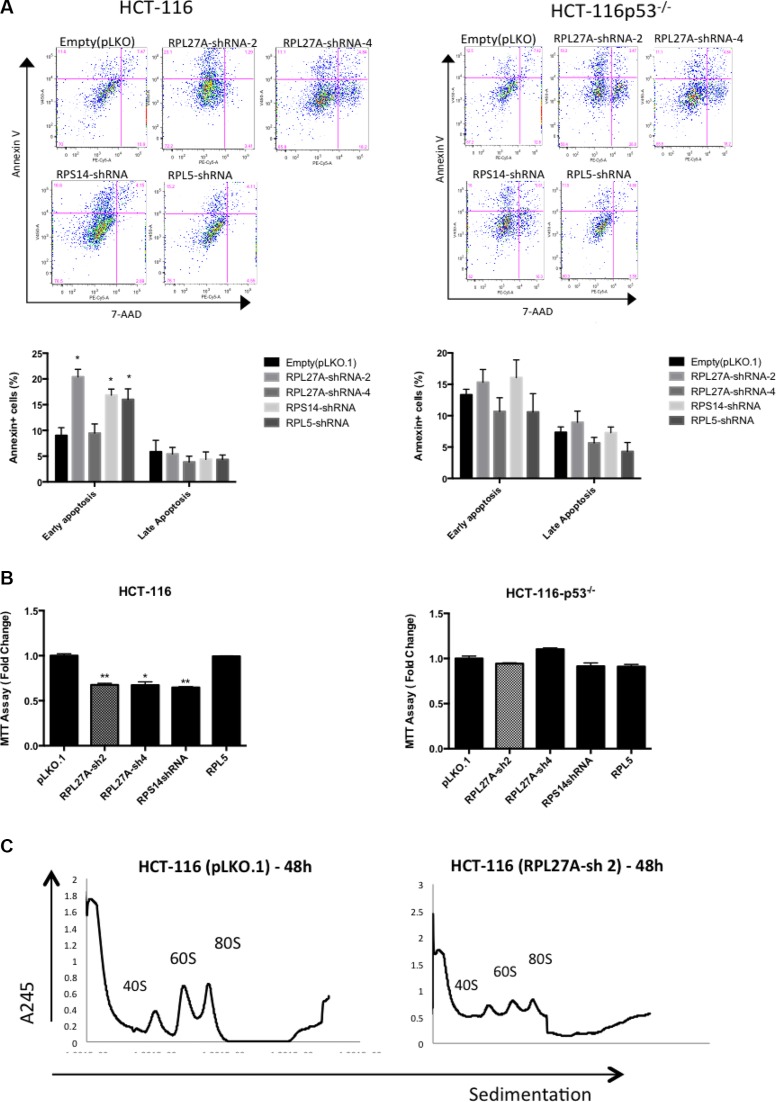

RPL27A knockdown in normal CD34+ cells reduces cell proliferation and induces p53

For Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) derived CD34+ cells, both RPL27A and RPS14 shRNA reduced the expression of RPL27A and RPS14 mRNA respectively by ≈70% compared to control (Figure 7A) and RPL27A knockdown was confirmed by western blot analysis (Figure 7C). Despite an apparent decrease in p53 mRNA expression in both RPL27A and RPS14 depleted cells, there was an increase in both p53 protein expression and p21 and Bax transcripts (Figure 7B and 7C). In addition, both RPL27A and RPS14 shRNA attenuated cellular proliferation as demonstrated by hypophosphorylation of Retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and a reduction in cell enumeration (Figure 7C, 7D).

Figure 7. RPL27A knockdown in normal CD34+ cells blocks haematopoietic stem cell proliferation and differentiation.

Normal CD34+ cells underwent infection either with control, RPL27A-shRNA or RPS14-shRNA and samples collected for analysis on Day 6. A significant reduction in RPL27A and RPL5 mRNA expression was evident following RPL27A-shRNA infection. Reduced RPS14 and RPL5 expression followed RPS14 shRNA infection (A). Upregulated expression of p53 mRNA and both p21 and Bax was induced following either RPL27A or RPS14 shRNA infection (B). Depletion of RPL27A and RPS14 also resulted in increased p53 protein expression and hypophosphorylation of phospho-Retinoblastoma (pRB) protein (C). Enumeration of cells at 48-hour intervals post infection demonstrated reductions in cell numbers following infection with either RPL27A-sh2 or RPS14-shRNA compared to controls (D). Methylcellulose colony formation assays were used to assess frequencies of progenitor cells following infection with either control, RPL27A-shRNA or RPS14 shRNA. In both RPL27A and RPS14 deficient cells, the most prominent reduction was in the erythroid lineage. Data is representative of 4 independent experiments, bars represent the mean ± SEM. CFU: colony forming unit including all colony types except erythroid; CFU-E: colony forming unit erythroid only (E–H). Flow cytometry was performed on cells harvested on Day 10/11 post infection. Cells were labelled with a combination of conjugated fluorometric antibodies including live/dead staining (780), an immature erythroid marker (CD71) and mature erythroid marker (Glycophorin A (GlyA)). Following either RPL27A-shRNA or RPS14 shRNA infection, a significant reduction in erythroid cells was evident compared with controls (I + J).

Next, we established the effect of RPL27A knockdown on erythroid cells. Erythroid differentiation was assessed on day 10 by flow cytometric expression of the erythroid- specific CD71 and Glycophorin A (GlyA) positive cells within the gated live cell population. Marked reductions in both immature and mature erythroid cells were evident in RPL27A and RPS14 deficient cells respectively (Figure 7E). Apoptosis was assessed by Annexin V staining and confirmed increased apoptosis in erythroid cells (Figure 7F). Lastly, RPL27A deficiency significantly blocked erythroid and granulocyte/ macrophages (GM) colony formation as assessed by clonogenic assays. The reduction in erythroid forming colonies was the most prominent finding (Figure 7G–7J).

miR-595, RPL27A and RPS14 expression in MDS patients

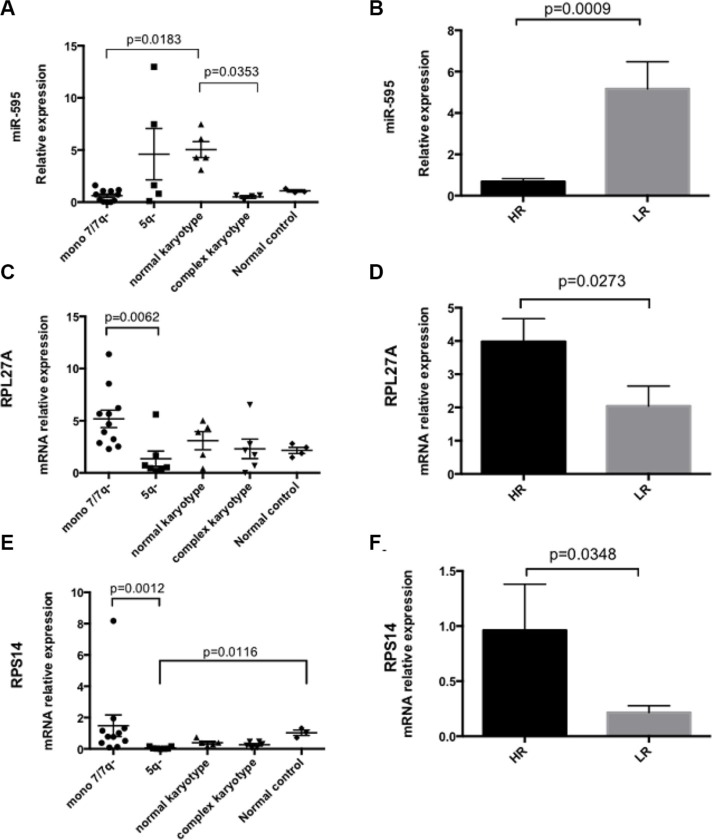

The relative expression of miR-595, RPL27A and RPS14 in bone marrow CD34+ cells derived from 29 MDS patients was compared to 4 controls. Supplementary Table S4 displays patient clinical details. As regards cytogenetics, 11 patients had −7/7q-, 6 patients had a complex karyotype inclusive of chromosome 7 anomalies, 7 patients had del5q and 5 patients had a normal karyotype. P53 mutational status was not available for all patients. The microRNA miR-595 was detected in 27/29 patients and 3/4 controls. Of note, miR-595 expression was significantly downregulated in MDS with −7/7q- MDS (n = 11) compared with normal karyotype MDS (n = 5). Furthermore, miR-595 was significantly downregulated in MDS with complex karyotype inclusive of chromosome 7 anomalies (n = 6) compared with normal karyotype MDS (n = 5) (Figure 8A). Of note, in this cohort, RPL27A was significantly upregulated in patients with −7/7q- compared with 5q- patients. No significant expression changes were identified between the −7/7q- cohort and other cytogenetic groups. Lastly, we compared miR-595 expression between IPPS High Risk (HR) and low risk (LR) groups. miR-595 expression appeared lower in HR disease when compared to LR disease, accompanied by higher expression of both RPL27A and RPS14 (Figure 8B–8F). These findings need confirmed in a larger cohort.

Figure 8. miR-595, RPL27A and RPS14 expression in MDS bone marrow CD34+ samples.

First, miR-595 expression was analysed in bone marrow CD34+ samples from 29 MDS patients (mir-595 was not detected in 2 patients). miR-595 expression was significantly downregulated in MDS with −7/7q- MDS (n = 11) compared with normal karyotype MDS (n = 5). Significant differential expression of miR-595 was also evident between CD34+ cells derived from MDS patients with complex karyotype containing chromosome 7 anomalies compared to those from MDS patients with a normal karyotype (A). miR-595 was significantly upregulated in LR MDS compared with HR MDS (B). Relative expression was calculated using the ΔΔCT method and RNU6B was used to normalize all samples. Bars represent mean ± SEM. Next, RPL27A, RPS14 and RPL5 expression was determined in BM CD34+ samples from the same 29 patient cohort (C–F); Four control CD34+ samples were available. RPL27A was significantly upregulated in patients with −7/7q- compared with 5q- patients. Re-analysis according to IPSS score (HR = 17 and LR = 12) demonstrated that RPL27A and RPS14 were significantly upregulated in HR MDS compared with LR MDS in this cohort. Bars represent mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

Our novel assay identified several putative targets of miR-595, a microRNA residing on chromosome 7, including RPL27A and HSPA14. We hereby confirm, for the first time, that the ribosomal subunit RPL27A is a target for miR-595. Downregulation of RPL27A expression, to model haploinsufficiency, induced p53-mRNA and protein expression, accompanied by upregulation of p21 and Bax, in the HCT-116 cell line and upregulation of p21 and Bax in HEL cells. In contrast, in p53 null cells, expression levels of p21 and Bax did not significantly change, implying that RPL27A, akin to other ribosomal proteins functions through p53-dependent mechanisms. This finding is consistent with a previous study investigating RPL27A in Sooty Foot Ataxia (SFA) mice [13–15, 17, 18, 25].

In our study, depletion of RPL27A, RPS14 and RPL5 reduced MDM2 mRNA and protein expression in all cell lines except the K562 cell line. Moreover, we demonstrate that endogenous RPL27A interacted with both MDM2 and RPL5 in HCT-116 cells. This suggests that RPL27A may well, at least in part, be working through MDM2 to influence p53 expression. The BLAST alignment of RPL27A and RPL5 sequences resulted in two regional alignments with 85–89% identities, which supported the concept of possible binding between both moieties. Moreover, a computational based protein interaction application (BioGrid) predicted possible binding of RPL27A with both MDM2 and RPL5.

Sh-RNA mediated silencing of RPL27A, RPS14 and RPL5 reduced proliferation capacity in both HEL and K562 cells, suggesting p53 independent effects. Decreased proliferation was additionally confirmed in the U937 p53 null cell line. We also show that RPL27A depletion in both p53 functional and null cells is associated with increased apoptosis, suggesting both p53-dependent and independent effects.

It is well established that mutations or altered expression of ribosomal proteins may lead to dysregulated ribosome generation. We show that RPL27A knockdown via RPL27A-sh2 led to depletion of the 60s subunit accompanied by an increase in the 40s subunit. Our findings contrast previous work in SFA mice where no effect on ribosome biogenesis was observed [17]. However, less efficient knockdown of RPL27A in that experimental setting may well explain this differing result. In addition, we highlight, for the first time, the importance of RPL27A in maintenance of nucleolar integrity and role in ribosome synthesis/maturation. Previous groups have suggested no effect on nucleolar integrity following either RPS14 or RPS19 knockdown [26, 27].

Knockdown of RPL27A in normal CD34+ cells resulted in increased p53 protein expression but not p53 mRNA, akin to what was observed in previous studies investigating RPS14 and RPS19 knockdown [18]. One potential reason for this finding is a global inhibition of translation due to associated ribosome dysgenesis. Furthermore, reduction of RPL27A significantly attenuated cell proliferation and induced apoptosis. These observations were also seen with RPS14 knockdown and were in agreement with other studies, linking ribosomal haploinsufficiency to p53 activation. However, our initial work, and that of others have demonstrated additional p53 independent effects of RPL27A knockdown [26–28]. Functionally, we show that RPL27A depletion impaired proliferation of CD34+ cells. Marked reductions in both immature and mature erythroid cells was evident in RPL27A deficient cells similar to the effect of RPL27 and RPS27 haploinsufficiency in DBA patients [29]. Of relevance, several other studies have described an upregulation of RPL27A during early erythroid development and hence suggest a pivotal role of RPL27A in erythropoiesis [30, 31]. For both −5q syndrome and DBA, mouse embryonic stem cell and zebra fish embryo models with depleted ribosomal proteins displayed anaemia regardless of p53 status, although we acknowledge the inherent limitations of these model systems [32–34].

Finally we demonstrated that miR-595 was significantly downregulated in MDS patients with −7/7q- compared with patients with normal karyotype. Interestingly, miR-595 was also significantly downregulated in MDS with complex karyotypes containing chromosome 7 anomalies and also when IPSS HR cases were compared to LR cases. Expression of RPL27A was higher in MDS with −7/7q- compared with 5q- MDS and also in HR-MDS compared with LR-MDS. These findings are in agreement with previous work correlating ribosomal protein overexpression with both disease aggressiveness and progression [35, 36]. The prognostic significance of RPL27A requires further validation in a larger patient cohort.

In summary we have described that miR-595, located on chromosome 7q36.3, is a pivotal miRNA regulator of RPL27A. In vitro we have demonstrated both p53-dependent and independent effects following RPL27A deficiency, including attenuated cellular proliferation, apoptosis and defective ribosomal biogenesis. It is evident that RPL27A depletion leads to a severe cellular insult, which appears to have a predilection for early erythroid cell development. We show that miR-595 was significantly downregulated in MDS patients with −7/7q- compared with patients with normal karyotype. Given the chromosomal location of miR-595, at 7q36.3, the clinical relevance of these findings will require further exploration in the context of MDS patients who display chromosome 7 anomalies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Methods not listed below are described in the online supplementary files

Cell culture and transfection

Adherent cells (MCF7, HeLa, HepG2, HCT-116 and HCT-116 p53−/−) were cultured in Dulbecco modified essential medium (DMEM) media. Suspension cells (K562, KG-1, HEL and U937) were cultured in RPMI 1640 media. Both culture media were supplemented with 10% (v/v) Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% (v/v) L- Glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% (v/v) sodium pyruvate. Cells were cultured under humidified condition at 37°C in a 5% CO incubator. The miRNA transfections and negative control pBabe transfections were performed using nucleofection technology according to the manufacturer's instructions (Lonza). The miRNA sequence is listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Novel functional assay for miR-595 identification

The micro-RNA miR-595 was cloned by PCR amplification of a ~1 Kb fragment obtained from human genomic DNA with primers incorporating the restriction sites BamHI and EcoRI. The resultant PCR fragment was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO vector using pCRII-TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and sequenced. Plasmid DNA was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and cloned into the retroviral vector, pBabepuro. The novel miRNA functional assay was performed as previously described (Gaken et al. 2012) The 3′untranslated region (3′UTR) cDNA library (MREH01, Sigma), derived from 10 different human tissues and 10 human cell lines and representing 16,923 unique genes, was cloned downstream of the TKzeo fusion gene into Sfi1 sites in a p3′TKzeo vector. Isolated genomic DNA from the functional assay was amplified by PCR with p3′TKzeo specific primers flanking the cloning site (Forward GGGTCGACCTCGAATCCTTA and Reverse CGAGGCGGCCGACATGTTT). The PCR product was sequenced directly to identify targets for miR-595. Target identification and validation was applied as previously described (Gaken et al. 2012).

Ribosome profiling

Cycloheximide was added to those cell lines under investigation to obtain a final concentration of 100 μg/mL followed by incubation in a tissue culture incubator for 15 minutes. Between 1–10 × 10 cells were subsequently harvested and washed with PBS containing 50 μg/mL Cycloheximide. Cell lysis, sucrose gradient centrifugation and polysome profiling were then performed as previously described (Fumagalli et al. 2009). Briefly, cells were lysed in polysome lysis buffer, incubated on ice for 15 minutes and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Equal lysate, according to the Optical Density (OD), was layered on top of a 10–50% (w/v) sucrose gradient and centrifuged for 1 hour and 57 minutes at 40,000 × g at 4°C in a SW41Ti rotor (Beckman). Gradients were fractionated using the polysome fractionator and Polysome profiles signals were detected using a UV monitor at A254.

Patient samples

This cohort incorporated 29 bone marrow samples from patients with MDS, which underwent CD34+ selection. Normal CD34+ cell products were obtained from our Haemato-Oncology Tissue Bank (Human Tissue Authority; licence number 12223). Samples were used in accordance with ethics approval given by the UK National Research Ethics Service (NRES) (Approval Reference 08/H0906/94).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6 (La Jolla, CA). Data was compared using paired t tests. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES AND TABLES

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Center of Excellence in Genomic Medicine Research (CEGMR) at King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia and King's College London and King's College NHS Foundation Trust for supporting this study. We are extremely grateful to Professor. Alan Warren and Dr. Shengjiang Tan for support in performing polysome profiling at the University of Cambridge. Lastly, we would like to thank Professor Mahvash Tavassoli for providing HCT-116 cell lines, Dr. Terry Gaymes for providing the myeloid cell lines, Professor. Shaun Thomas, for supplying pRB antibody and Dr. Jie Jiang for providing the RPS14 lentivirus shRNA and the empty vector, pLKO.1.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Authors' Contributions

H.A was involved with all aspects of the study's design, execution, analysis, and manuscript preparation. G.J.M and J.G contributed equally to study design, analysis, manuscript preparation and project leadership. D.M and A.K contributed to data interpretation and manuscript preparation. FM contributed to the miRNA functional assay and cloning and amplification of the cDNA library. D.D contributed to lentivirus production and T.S contributed to flow cytometric analysis and data interpretation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;16:350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. 431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaken J, Mohamedali AM, Jiang J, Malik F, Stangl D, Smith AE, Chronis C, Kulasekararaj AG, Thomas NS, Farzaneh F, Tavassoli M, Mufti GJ. A functional assay for microRNA target identification and validation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Didiano D, Hobert O. Perfect seed pairing is not a generally reliable predictor for miRNA-target interactions. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:849–51. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodersen P, Voinnet O. Revisiting the principles of microRNA target recognition and mode of action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:141–8. doi: 10.1038/nrm2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst T, Chase AJ, Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis CE, Bryant C, Jones AV, Waghorn K, Zoi K, Ross FM, Reiter A, Hochhaus A, Drexler HG, Duncombe A, et al. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat Genet. 2010;42:722–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Fidler C, Nadig N, Giagounidis A, Della Porta MG, Malcovati L, Killick S, Gattermann N, Aul C, Boultwood J, Wainscoat JS. Genome-wide analysis of copy number changes and loss of heterozygosity in myelodysplastic syndrome with del(5q) using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Haematologica. 2008;93:994–1000. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horiike S, Taniwaki M, Misawa S, Abe T. Chromosome abnormalities and karyotypic evolution in 83 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and predictive value for prognosis. Cancer. 1988;62:1129–38. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880915)62:6<1129::aid-cncr2820620616>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Philip P, Larsen SO, Jensen G, Byrsting K. Chromosome aberrations and prognostic factors in therapy-related myelodysplasia and acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1990;76:1083–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu JM, Ellis SR. Ribosomes and marrow failure: coincidental association or molecular paradigm? Blood. 2006;107:4583–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narla A, Ebert BL. Ribosomopathies: human disorders of ribosome dysfunction. Blood. 2010;115:3196–205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-178129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marechal V, Elenbaas B, Piette J, Nicolas JC, Levine AJ. The ribosomal L5 protein is associated with mdm-2 and mdm-2-p53 complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7414–20. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panić L, Tamarut S, Sticker-Jantscheff M, Barkić M, Solter D, Uzelac M, Grabusić K, Volarević S. Ribosomal protein S6 gene haploinsufficiency is associated with activation of a p53-dependent checkpoint during gastrulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8880–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00751-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson SJ, Lauritsen JP, Hartman MG, Foushee AM, Lefebvre JM, Shinton SA, Gerhardt B, Hardy RR, Oravecz T, Wiest DL. Ablation of ribosomal protein L22 selectively impairs alphabeta T cell development by activation of a p53-dependent checkpoint. Immunity. 2007;26:759–72. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barkić M, Crnomarković S, Grabusić K, Bogetić I, Panić L, Tamarut S, Cokarić M, Jerić I, Vidak S, Volarević S. The p53 tumor suppressor causes congenital malformations in Rpl24-deficient mice and promotes their survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2489–504. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01588-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danilova N, Sakamoto KM, Lin S. Ribosomal protein S19 deficiency in zebrafish leads to developmental abnormalities and defective erythropoiesis through activation of p53 protein family. Blood. 2008;112:5228–37. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebert BL, Pretz J, Bosco J, Chang CY, Tamayo P, Galili N, Raza A, Root DE, Attar E, Ellis SR, Golub TR. Identification of RPS14 as a 5q- syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature. 2008;451:335–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin A, Itahana K, O'Keefe K, Zhang Y. Inhibition of HDM2 and activation of p53 by ribosomal protein L23. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7669–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7669-7680.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Wolf GW, Bhat K, Jin A, Allio T, Burkhart WA, Xiong Y. Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53-dependent ribosomal-stress checkpoint pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8902–12. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8902-8912.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai MS, Lu H. Inhibition of MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation by ribosomal protein L5. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44475–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takagi M, Absalon MJ, McLure KG, Kastan MB. Regulation of p53 translation and induction after DNA damage by ribosomal protein L26 and nucleolin. Cell. 2005;123:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhat KP, Itahana K, Jin A, Zhang Y. Essential role of ribosomal protein L11 in mediating growth inhibition-induced p53 activation. EMBO J. 2004;23:2402–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lohrum MA, Ludwig RL, Kubbutat MH, Hanlon M, Vousden KH. Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:577–87. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Hao Q, Liao J, Zhang Q, Lu H. Ribosomal protein S14 unties the MDM2-p53 loop upon ribosomal stress. Oncogene. 2013;32:388–96. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Draptchinskaia N, Gustavsson P, Andersson B, Pettersson M, Willig TN, Dianzani I, Ball S, Tchernia G, Klar J, Matsson H, Tentler D, Mohandas N, Carlsson B, et al. The gene encoding ribosomal protein S19 is mutated in Diamond-Blackfan anaemia. Nat Gen. 1999;21:169–75. doi: 10.1038/5951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dutt S, Narla A, Lin K, Mullally A, Abayasekara N, Megerdichian C, Wilson FH, Currie T, Khanna-Gupta A, Berliner N, Kutok JL, Ebert BL. Haploinsufficiency for ribosomal protein genes causes selective activation of p53 in human erythroid progenitor cells. Blood. 2011;117:2567–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fumagalli S, Di Cara A, Neb-Gulati A, Natt F, Schwemberger S, Hall J, Babcock GF, Bernardi R, Pandolfi PP, Thomas G. Absence of nucleolar disruption after impairment of 40S ribosome biogenesis reveals an rpL11-translation-dependent mechanism of p53 induction. Nat Cell Bio. 2009;11:501–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pellagatti A, Marafioti T, Paterson JC, Barlow JL, Drynan LF, Giagounidis A, Pileri SA, Cazzola M, McKenzie AN, Wainscoat JS, Boultwood J. Induction of p53 and up-regulation of the p53 pathway in the human 5q- syndrome. Blood. 2010;115:2721–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang R, Yoshida K, Toki T, Sawada T, Uechi T, Okuno Y, Sato-Otsubo A, Kudo K, Kamimaki I, Kanezaki R, Shiraishi Y, Chiba K, Tanaka H, et al. Loss of function mutations in RPL27 and RPS27 identified by whole-exome sequencing in Diamond-Blackfan anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:854–64. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.da Cunha AF, Brugnerotto AF, Duarte AS, Lanaro C, Costa GG, Saad ST, Costa FF. Global gene expression reveals a set of new genes involved in the modification of cells during erythroid differentiation. Cell Prolif. 2010;43:297–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebert BL, Lee MM, Pretz JL, Subramanian A, Mak R, Golub TR, Sieff CA. An RNA interference model of RPS19 deficiency in Diamond-Blackfan anemia recapitulates defective hematopoiesis and rescue by dexamethasone: identification of dexamethasone-responsive genes by microarray. Blood. 2005;105:4620–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narla A, Payne EM, Abayasekara N, Hurst SN, Raiser DM, Look AT, Berliner N, Ebert BL, Khanna-Gupta A. L-Leucine improves the anaemia in models of Diamond Blackfan anaemia and the 5q- syndrome in a TP53-independent way. Br. J Haematol. 2014;167:524–8. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh SA, Goldberg TA, Henson AL, Husain-Krautter S, Nihrane A, Blanc L, Ellis SR, Lipton JM, Liu JM. p53-Independent cell cycle and erythroid differentiation defects in murine embryonic stem cells haploinsufficient for Diamond Blackfan anemia-proteins: RPS19 versus RPL5. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teng T, Mercer CA, Hexley P, Thomas G, Fumagalli S. Loss of tumor suppressor RPL5/RPL11 does not induce cell cycle arrest but impedes proliferation due to reduced ribosome content and translation capacity. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:4660–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01174-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sridhar K, Ross DT, Tibshirani R, Butte AJ, Greenberg PL. Relationship of differential gene expression profiles in CD34+ myelodysplastic syndrome marrow cells to disease subtype and progression. Blood. 2009;114:4847–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendiburu CF, Silva WA, Jr, Ricci O, Jr, Bonini-Domingos CR, Fett-Conte AC. Global gene expression profile in myelodysplastic syndromes using SAGE. Genet Mol Res. 2008;7:1245–50. doi: 10.4238/vol7-4gmr521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.