Abstract

Background

In sublingual immunotherapy, optimal doses are a key factor for therapeutic outcomes. The aim of this study with tablets containing carbamylated monomeric house dust mite allergoids was to determine the most effective and safe dose.

Methods

In this double‐blind, placebo‐controlled dose‐finding study, 131 patients with house dust mite‐induced allergic rhinoconjunctivitis were randomized to 12‐week treatments with 300 UA/day, 1000 UA/day, 2000 UA/day, 3000 UA/day or placebo. Conjunctival provocation tests (CPT) were performed before, during and after treatment. The change in mean allergic severity (primary endpoint), calculated from the severity of the CPT reaction, and the proportion of patients with an improved CPT threshold (secondary endpoint) determined the treatment effect.

Results

The mean allergic severity decreased in all groups, including the placebo group. It was lower in all active treatment groups (300 UA/day: 0.14, 1000 UA/day: 0.15, 2000 UA/day: 0.10, 3000 UA/day: 0.15) than in the placebo group (0.30). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P < 0.1). The percentage of patients with an improved CPT threshold was higher in the active treatment groups (300 UA/day: 73.9%; 1000 UA/day: 76.0%; 2000 UA/day: 88.5%; 3000 UA/day: 76.0%) than in the placebo group (64.3%). The difference between placebo and 2000 UA/day was statistically significant (P = 0.04). In 13 (10%) exposed patients, a total of 20 treatment‐related adverse events of mild severity were observed.

Conclusions

The 12‐week daily treatment using 2000 UA/day monomeric allergoid sublingual tablets is well tolerated and reduces the CPT reaction in house dust mite‐allergic patients.

Keywords: allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, carbamylated monomeric allergoid tablets, dose‐finding study, house dust mites, sublingual immunotherapy

The efficacy and safety of sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for house dust mite (HDM)‐induced allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (AR) is a matter of intense debate. While evidence for the efficacy of SLIT in HDM‐induced AR has often been weak, not only because of small study sizes, but also because of house dust mite‐specific problems in designing studies (e.g. the lack of reliable endpoint parameters or difficulty in measuring allergen exposure), sound scientific proof of the efficacy of SLIT has begun to accumulate 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. However, the optimal dosing depends on the product used for SLIT and is often still unclear 3, 6. A meta‐analysis has demonstrated the efficacy and safety of house dust mite SLIT using tablets with carbamylated allergoids 7, but the cumulative doses shown to be effective in the various studies differed widely. Hence, in this placebo‐controlled study, we aimed to determine the optimal dose of four different daily dosages for SLIT with carbamylated monomeric allergoid tablets in patients suffering from HDM‐induced AR with or without asthma.

Allergen challenges such as the nasal provocation test (NPT) or the conjunctival provocation test (CPT) are recommended to prove the clinical relevance of HDM as the cause of a patient's AR 3 and may be used as a primary outcome parameter for early dose‐finding studies such as this one 8. The CPT has been shown to have a very high correlation with the NPT and a similar, if not better, correlation with medical history, skin prick tests and specific IgE reactivity than the NPT in patients suffering from HDM‐induced AR 9, 10. Of note, these results were valid regardless of whether patients suffered from allergic rhinoconjunctivitis or allergic rhinitis alone. Therefore, we decided to use the CPT as the primary endpoint for both allergic conjunctivitis and allergic rhinitis in this dose‐finding study.

Methods

Study design

This was a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre, parallel, five‐arm phase II study performed at 16 outpatient allergy centres in Germany. After a screening visit (V0), eligible subjects were randomized (1 : 1 : 1 : 1 : 1) to one of the four active treatment groups or to the placebo group at the following visit (V1) and received sublingual tablets for 12 weeks to be taken on a daily basis.

Subjects

Eligible subjects for this trial were men and women aged 18 to 75 years with a history of at least 2 years of HDM‐induced allergic rhinitis and/or allergic rhinoconjunctivitis with or without controlled asthma upon exposure to HDM 11. Other main inclusion criteria were specific IgE reactivity to mite allergens (CAP‐RAST ≥ Class 2, corresponding to ≥0.70 kU/ml allergen‐specific IgE), positive skin prick test (wheal diameter ≥3 mm, negative control <2 mm; manufacturer ALK‐Abelló, Hørsholm, Denmark) and positive response to conjunctival provocation testing (CPT). Patients with clinically relevant cosensitizations to perennial allergens such as animal dander could be included if they were not regularly exposed. The main exclusion criteria were predominant seasonal AR, partly or fully uncontrolled asthma, existing or intended pregnancy and intake of unallowed concomitant medication (e.g. antihistamines, psychoactive medication).

Study medication

The study medication (including placebo) was manufactured by Lofarma, S.p.A., Milan, Italy. The tablets consisted of a 1 : 1 mixture of carbamylated monomeric Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae allergoids and were standardized in allergy units (UA), with 1 UA corresponding to 1/40 of the mean provocation dosage of the comparable unmodified allergen determined by nasal provocation tests (NPT) in patients suffering from AR. During the treatment phase of 84 days, the patients received daily dosages of a placebo preparation or one of four different active strengths: 300 UA/day, 1000 UA/day, 2000 UA/day or 3000 UA/day (cumulative doses for the 84 days of treatment were 25 200–252 000 UA). According to a publication by Di Gioacchino, 1000 UA correspond to 2.7 μg of group 1 mite allergen and 3000 UA to 8.1 μg of group 1 mite allergen 12.

Study endpoints

A CPT with a HDM solution (manufactured by ALK‐Abelló) was performed at the screening visit (V0), the visit before the first tablet intake (V1, Day 0), V3 (Day 28 ± 14) and the final visit V4 (Day 84 ± 11). Before the CPT was conducted, investigators confirmed that the eyes were without irritation, otherwise the test had to be postponed. Then, increasing concentrations containing 100, 1000 and 10 000 SQ‐U/ml were applied to one eye and a control solution containing only the diluent to the other eye. Conjunctival symptoms were evaluated 10 min after each titration. Possible reaction stages (Table 1) were graded according to Riechelmann 9. A CPT response of stage II or higher was considered positive. Then, the CPT was stopped, the eye was rinsed with water and a topical antihistamine was applied, if necessary.

Table 1.

Possible reactions to the CPT according to Riechelmann 9. Reactions of Stage II or higher were considered positive 13

| Stage | Findings |

|---|---|

| 0 | No subjective or visible reaction |

| I | Itching, reddening, foreign body sensation |

| II | Stage I and in addition tearing, vasodilation of conjunctiva bulbi |

| III | Stage II and in addition vasodilation and erythema of conjunctiva tarsi, blepharospasm |

| IV | Stage III and in addition chemosis, lid swelling |

The primary efficacy outcome parameter was the change in the allergic severity between baseline and the final visit V4, calculated from the reaction to the CPT as documented in the case report form. Allergic severity (S), as defined by Astvatsatourov 13, takes into account the reactions to the different allergen concentrations:

‘c 1’, ‘c 2’ and ‘c 3’ were the documented reaction stages of the CPT (e.g. 1 = itching, reddening, foreign body sensation) at the different concentrations (100, 1000 and 10 000 SQ‐U/ml), and N was the number of concentrations 1, 2, 3 needed for a positive CPT. For example, if a patient had no reaction (reaction stage 0) to the 100 SQ‐U/ml and 1000 SQ‐U/ml solutions but showed itching, reddening and a vasodilation of the conjunctiva bulbi (reaction stage 2) at 10 000 SQ‐U/ml, the CPT was positive at 10 000 SQ‐/ml and S was calculated as follows:

If the CPT results from V0 and V1 differed, the smaller S, corresponding to an earlier CPT reaction, was defined as the baseline value. The mean improvement was calculated as the absolute difference between baseline and V4 and as relative improvement (in per cent).

As secondary efficacy outcome parameter, the change in the CPT response threshold (improved/not improved) was analysed. All conjunctival provocations were documented by high‐definition macroimages 14 for optional external rating and digital image analysis.

A global evaluation of the therapy was carried out at the final visit V4. The physicians were asked to rate the efficacy and tolerability, and patients were asked to evaluate their satisfaction with treatment and whether they would recommend treatment on a four‐point scale from 0 to 3, with 3 being the best rating.

The safety endpoints comprised the occurrence and severity of adverse events (AEs). All AEs except for those rated as definitely ‘not related’ by the investigators were regarded as treatment‐related AEs (TRAEs).

Sample size calculation

As there are no previous studies assessing S as a primary endpoint, the sample size was estimated based on the results of the calculation of S in a dose‐finding study for carbamylated allergoid tree pollen tablets. Assuming that the mean improvement would be 0.2 in the placebo group and 0.3 for the optimal dose and that the variance would be 0.1 for both, a sample size of 22 patients per group would be sufficient to obtain an α < 0.05 and a power of 90%.

Randomization and blinding

A computer‐based randomization list with a block size of 10 patients was generated for 250 patients. Patients were allocated to the next random treatment number by the investigators in consecutive and ascending order. Blinding of the patients and the investigators was ensured by the identical size, shape, weight, colour, taste and smell of study medication and packaging. For emergencies, the investigators received a sealed envelope for each of their patients that contained the details of the treatment to which the individual patient had been allocated.

Statistical method

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Individual comparisons were performed by a nonparametric test (Mann–Whitney U‐test or Wilcoxon test). The significance level was set at α = 0.05. The analysis was based on the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population comprising all randomized patients with at least a valid CPT at baseline and after therapy. The safety population consisted of all randomized patients.

Ethical conduct of the study

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, good clinical practice (GCP) guidelines and the requirements of national laws 15, 16. All study documents were approved by independent ethics committees (primary responsible ethics committee: Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer Nordrhein: 2013125, Eudra‐CT: 2013‐000617‐20) and by the national regulatory agency of the German Federal Ministry of Health (Paul Ehrlich Institute). Patients were covered by insurance and gave written informed consent before any study procedures were applied.

Results

Trial population

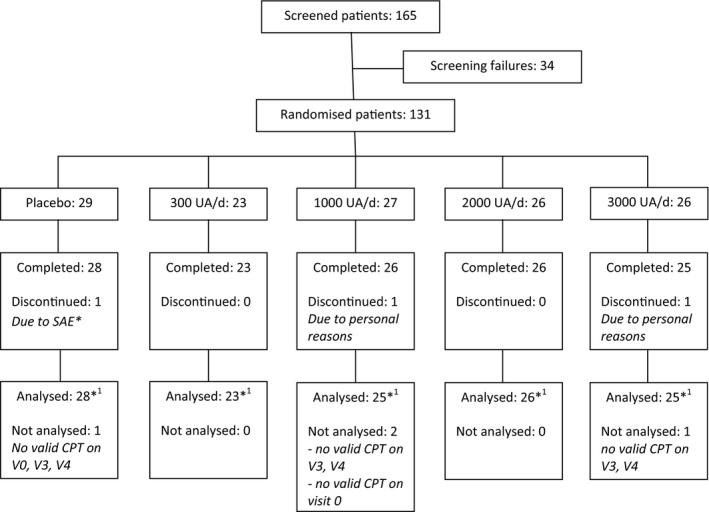

In total, 165 patients were screened for this study. Of these, 131 patients who fulfilled all inclusion criteria were randomized and 128 completed the study (Fig. 1). Throughout the trial, three dropouts were recorded: two patients stated personal reasons, and one patient from the placebo group terminated the study earlier because she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Overall, four patients had to be excluded from the ITT population due to missing CPT results, resulting in an ITT population of 127 patients. Demographic and baseline characteristics such as sex, age, asthmatic status and allergic parameters were distributed comparably among the five groups (Table 2). The use of nasal steroids during the study, which was not restricted and therefore might have been a major confounder, was low and comparable among all groups (0–2 patients/group).

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. *The serious adverse event (SAE) was the treatment‐unrelated occurrence of breast cancer. *1Analysed patients for ITT, all randomized patients were included in the safety set.

Table 2.

Demographic data and selected baseline characteristics

| All patients | Placebo | 300 UA/day | 1000 UA/day | 2000 UA/day | 3000 UA/day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 127 | 28 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 25 |

| Age [years, mean] | 37.5 | 38.2 | 36 | 34.6 | 38.7 | 39.6 |

| Sex [n female (%)] | 63 (49.6) | 12 (42.9) | 11 (47.8) | 14 (56.0) | 14 (53.8) | 12 (48.0) |

| Height [cm, mean] | 174.8 | 174.8 | 176.8 | 173.8 | 174.9 | 174 |

| Weight [kg, mean] | 77.3 | 78.7 | 77.7 | 78.9 | 72.2 | 79.6 |

| Asthma [n patients (%)] | 30 (23.6) | 6 (21.4) | 6 (26.1) | 5 (20.0) | 5 (19.2) | 8 (31.0) |

| History of ARa [years, mean] | 14.6 | 18.3 | 14.1 | 12.6 | 14.1 | 13.3 |

| Monosensitizedb [n patients, (%)] | 52 (40.9) | 13 (46.4) | 11 (47.8) | 11 (44.0) | 6 (23.1) | 11 (44.0) |

| Polysensitizedb [n patients, (%)] | 75 (59.1) | 15 (53.6) | 12 (52.2) | 14 (56.0) | 20 (76.9) | 14 (56.0) |

| SPT diameter [mm, mean] | ||||||

| Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus | 8.7 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 8.6 |

| Dermatophagoides farinae | 7.9 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 8.3 | 7.9 |

| Specific IgE [CAP‐RAST, mean] | ||||||

| Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| Dermatophagoides farinae | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.6 |

AR, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.

Monosensitized/polysensitized according to skin prick test results.

Primary efficacy endpoint

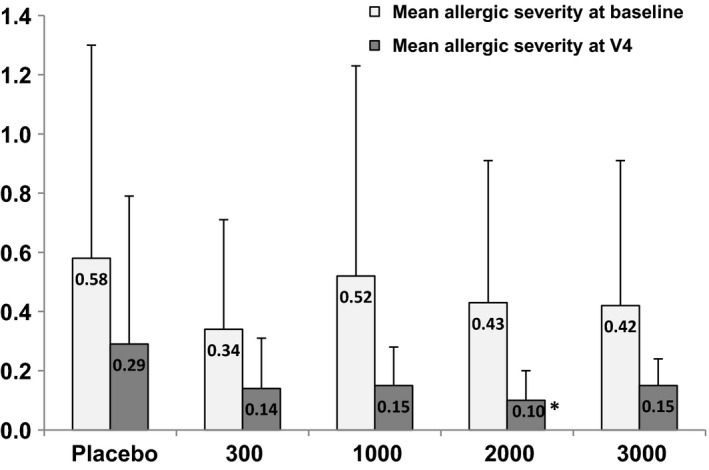

The mean S decreased in all study groups, including the placebo group, during the course of the trial (Table 3). At the end of the treatment (V4), the mean S in the four active treatment groups was only one‐third to one‐half of the mean S in the placebo (S(Placebo) = 0.29, S(300 UA/day) = 0.14, S(1000 UA/day) = 0.15, S(2000 UA/day) = 0.10, S(3000 UA/day) = 0.15), favouring the treatment group 2000 UA/day although not significant (P < 0.1, Fig. 2). The absolute reduction was highest in the 1000 UA/day group (0.37); however, it was not significantly higher than placebo (0.30).

Table 3.

Trial results

| Placebo | 300 UA/day | 1000 UA/day | 2000 UA/day | 3000 UA/day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean allergic severity at baseline (SD) | 0.58 (0.72) | 0.34 (0.37) | 0.52 (0.71) | 0.43 (0.48) | 0.42 (0.49) |

| Mean allergic severity at V3 (SD) | 0.40 (0.57) | 0.26 (0.39) | 0.24 (0.38) | 0.26 (0.37) | 0.34 (0.52) |

| Mean allergic severity at V4 (SD) | 0.29 (0.50) | 0.14 (0.17) | 0.15 (0.13) | 0.10 (0.10) | 0.15 (0.09) |

| Delta allergic severity baseline‐V4 (SD) | 0.30 (0.50) | 0.20 (0.37) | 0.37 (0.74) | 0.33 (0.46) | 0.27 (0.48) |

| Percentage of patients with improved Allergic severity at V4 | 75.0 | 82.6 | 88.0 | 88.5 | 76.0 |

| Percentage of patients reacting to CPT at V4 | 39.3 | 34.8 | 28.0 | 19.2 | 32.0 |

| Global evaluation of efficacy (0–3)a | 1.96 | 2.13 | 2.24 | 2.27 | 2.04 |

| Global evaluation of tolerability | |||||

| (0–3)b | 2.89 | 2.96 | 3.00 | 2.81 | 2.92 |

| Global evaluation of patients’ satisfaction (0–3)c | 2.11 | 2.17 | 2.40 | 2.23 | 1.92 |

| Global evaluation of patients’ recommendation (0–3)d | 2.41 | 2.35 | 2.56 | 2.54 | 2.16 |

0 = worsened, 1 = unchanged, 2 = slight‐to‐moderate improvement, 3 = good‐to‐excellent improvement.

0 = poor, 1 = satisfactory, 2 = good, 3 = very good.

0 = dissatisfied, 1 = somewhat satisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = very satisfied.

0 = ‘I would definitely not recommend the therapy’, 1 = ‘I would probably not recommend the therapy’, 2 = ‘I would probably recommend the therapy’, 3 = ‘I would definitely recommend the therapy’.

Figure 2.

Allergic severity S at baseline and at V4. *P < 0.1 when compared to placebo.

The number of patients with an improved S at V4 was highest for 2000 UA/day (88.5%) and 1000 UA/day (88.0%). It was higher in all treatment groups (82.6% in the group 300 UA/day and 76.0% in the group 3000 UA/day) than in the placebo group with an improvement rate of 75.0%. Regarding the aim of this trial to show a decrease in allergic symptoms by a high number of nonreactive patients with a negative CPT reaction at V4, patients treated with 2000 UA/day had the lowest reaction rate, with only 19.2% still reacting in the final CPT. The percentage of patients with a positive CPT reaction was highest for placebo group patients (39.3%). However, these differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

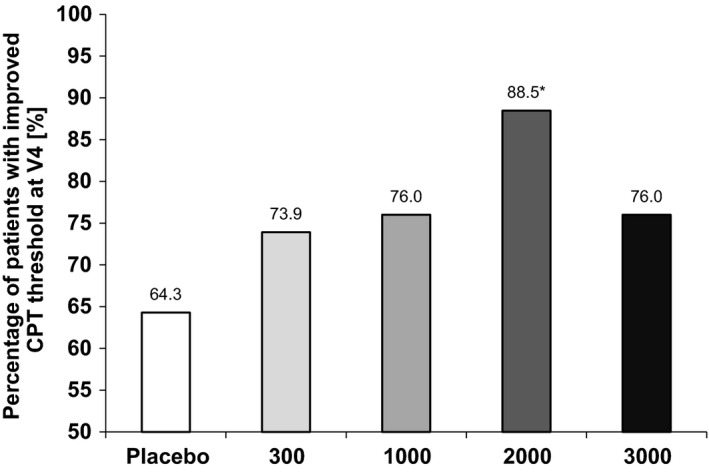

Secondary efficacy endpoints

The analysis of patients who showed an improved CPT response threshold at the end of the study revealed a statistically significant difference between the group treated with 2000 UA/day and the placebo group (P = 0.04). While the smallest improvement rate (64.3%) regarding this CPT parameter was seen in the placebo group, it was higher in the actively treated groups, with 73.9% of patients in group 300 UA/day showing an improved response threshold and 76.0% of patients both in groups 1000 and 3000 UA/day. The percentage of improved patients was highest in the group receiving 2000 UA/day (88.5%, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients with an improved CPT response threshold at V4. *Significant when compared to placebo (P = 0.04).

Finally, the results of the global evaluation made by investigators and patients at the end of the study attribute high tolerability and acceptance to the investigational products. The three parameters ‘tolerability’, ‘satisfaction’ and ‘recommendation of therapy’ received the most favourable rating by patients treated with 1000 UA/day, while the ‘overall efficacy’ was rated the best by patients treated with 2000 UA/day. However, compared to placebo or other active dosages, none of the differences were statistically significant (Table 3).

Safety endpoints

During the course of the study, only few and mild treatment‐related AEs were observed. Overall, 50 AEs occurred in 37 (28%) of the exposed patients. Of these AEs, 20 were categorized as treatment‐related and reported by 13 (10%) patients (Table 4). Local reactions such as oral pruritus or ear pruritus made up nine (45%) TRAEs in seven patients. Six TRAEs were classified as mild systemic reactions (such as rhinorrhoea and sneezing), three were unspecific systemic reactions (such as headache) and two reactions (a herpes infection and a weight gain of 8 kg) fell into none of these categories. The majority (70%) of the TRAEs occurred after the first or second tablet intake. The percentage of patients with at least one TRAE was lowest in the placebo group (3.4%) and highest in the group 3000 UA/day (19.2%). Local reactions occurred in 3.4% of the patients in the placebo group and in a maximum of 7.7% of the patients in the active treatment groups 2000 and 3000 UA/day.

Table 4.

TRAEs in the safety population per study group

| TRAEs | Placebo | 300 UA | 1000 UA | 2000 UA | 3000 UA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local TRAEs (n = 9) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| Oropharyngeal blistering | 1 | |||||

| Swollen tongue | 1 | |||||

| Oral discomfort | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Oral pruritus | 1 | |||||

| Hypoaesthesia oral | 1 | |||||

| Increased upper airway secretion | 1 | |||||

| Throat irritation | 1 | |||||

| Glossodynia | 1 | |||||

| Systemic TRAEs (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Ear pruritus | 1 | |||||

| Sneezing | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Rhinorrhoea | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Wheezing | 1 | |||||

| Unspecific TRAEs (n = 3) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Dysgeusia | 1 | |||||

| Malaise | 1 | |||||

| Blood glucose increased | 1 | |||||

| Unclassified TRAEs (n = 2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Herpes virus infection | 1 | |||||

| Weight increase | 1 | |||||

| Total TRAEs (n = 20) | 1 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

Discussion

This is the first double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial that could show a statistically significant superiority of HDM‐induced AR treatment with a carbamylated monomeric allergoid after a treatment course of only 12 weeks. Nonetheless, this study failed to show a statistically significant superiority over placebo in the primary endpoint, while it could show statistically significant superiority in the second outcome parameter. The efficacy of specific immunotherapy with this product over treatment periods of 1 year or longer has already been demonstrated in other trials 17, 18. In comparison, a recent double‐blind, placebo‐controlled house dust mite SLIT study investigating another product could show a statistically significant treatment effect only after at least 4 months of treatment 19.

The CPT is a viable surrogate parameter for symptoms and may be used as a primary outcome parameter in phase II studies 8. In the present study, the analysis of the CPT results by means of S 13 favours the active treatment dose of 2000 UA/day when compared to placebo. The percentage of patients showing no positive CPT reaction at the final visit underlines this difference. Likewise, the percentage of patients having an improved CPT threshold at the final visit is significantly higher in the group treated with 2000 UA/day than in the placebo group.

The improvement of the S was strong in all groups of this study, probably because most of the patients included had suffered from mild HDM allergy and only reacted to the highest CPT concentration of 10 000 SQ‐U/ml at baseline. In future studies, the use of higher CPT threshold doses might be considered to better depict the treatment effect. As the biological activity of the applied diagnostic solution was demonstrated to be about three times higher in the tree and grasses product than in the HDM solution, thresholds of 300 SQ‐U/ml, 3000 SQ‐U/ml and 30 000 SQ‐U/ml may be more appropriate for future studies 20.

The number of placebo group patients with an improved CPT result was unexpectedly high in this study. Even for the CPT threshold, which appears to be most suitable for depicting differences between the groups, an improvement by at least one step was recorded for 64% of the placebo group patients. However, this is not unusual and has been reported by other authors using this provocation model. In two studies investigating an allergen‐free immune modulator and grass pollen subcutaneous immunotherapy, Klimek et al. reported an improvement of 40% and 50% in placebo patients 21, 22. In a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial investigating HDM subcutaneous immunotherapy, Riechelmann found that 30% of the placebo group patients and 51% of the actively treated patients had an improved CPT threshold 23. Possible reasons for the good placebo performance in this study may be a habituation to CPT with the diagnostic solution (although Riechelmann could not observe any indicators for this) or the lower number of placebo group patients in this trial. A local desensitization effect of the CPT may also have played a role 24. Only two of ten patients the investigators saw were placebo group patients, so that the raters might have unintentionally transferred the positive results of the actively treated majority of patients to the placebo group patients. Methodical problems in the performance of the CPT seem unlikely, as a separate analysis of pictures taken during the CPT by the central observers showed a very high correlation between the results of the investigators and central observers. Furthermore, it is possible that seasonal changes in HDM exposure might have influenced the reactivity in the course of the study and cannot be ruled out as a confounder, because HDM exposure was not measured in this study. However, the absolute difference of patients with an improved CPT threshold between the most favourable active treatment group receiving 2000 UA/day and the placebo group in this study (24%) was in the same order of that determined by Riechelmann (21%) 23. Whatever the reason for the good placebo performance, it seems to have had no influence on the treatment effect when comparing the placebo group with the active treatment groups.

The favourable safety profile in this study corresponds to that observed in other studies 12, 17, 18, 25, 26, 27, 28 and has been confirmed in a meta‐analysis 7. SLIT studies using native allergens are often confounded by the high rate of local side‐effects in the actively treated groups that may unblind patient and investigator. In our study, however, this confounding factor does not apply because the number of patients reporting local AEs was small and distributed relatively evenly among all study groups (3.4% in the placebo group and a maximum of 7.7% in the treatment groups). The incidence of local AEs with the investigated product in this study was at least one order of magnitude lower than the ones reported with tablets containing natural allergens 19, 29.

A possible limitation of this study is the lacking evaluation of the patients’ symptoms and rescue medication intake, which are usually recommended as primary endpoints 30, 31.

Overall, the 12‐week course of treatment with carbamylated monomeric allergoids in this study reliably decreased CPT reactions in patients suffering from HDM‐induced allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Although the improvement of the absolute mean allergic severity value was numerically higher in the group receiving 1000 UA/day, the other results of the patients benefiting from treatment favour a daily dose of 2000 UA/day to reach a significant treatment effect after 12 weeks.

Authors’ contributions

CH and PD wrote the study report and conducted the literature research, CH wrote the manuscript, JS was responsible for the data management, SA for the study coordination, KS and WL performed the statistical analysis and RM designed the study with the support of EC and SA. All authors critically revised and commented on the manuscript at all stages and made valuable contributions to it.

Conflict of interest

This study was sponsored by Lofarma S.p.A., Milano, Italy. EC is an employee of Lofarma. SA received personal fees from Lofarma. RM received personal fees from ALK‐Abello, personal fees from Allergy Therapeutics, personal fees from Allergopharma, grants and personal fees from Bencard, grants and personal fees from BiotechTools, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from GSK, grants from HAL, personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, grants and personal fees from Lofarma, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Menarini, personal fees from Faes, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Leti, grants from Optima, nonfinancial support from Greer, nonfinancial support from Roxall, grants from AIPrevent, personal fees from Servier, personal fees from Stada, grants and personal fees from Stallergènes, personal fees and nonfinancial support from UCB, grants from Ursapharm, grants from Bitop, grants from Hulka, nonfinancial support from Atmos, grants and personal fees from Arthrocare, personal fees from Meda, personal fees from Ohropax, outside the submitted work. There are no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gena Kittel and Marie‐Josefine Joisten for their valuable editorial assistance and helpful comments.

Hüser C, Dieterich P, Singh J, Shah‐Hosseini K, Allekotte S, Lehmacher W, Compalati E, Mösges R. A 12‐week DBPC dose‐finding study with sublingual monomeric allergoid tablets in house dust mite‐allergic patients. Allergy 2017; 72: 77–84.

Edited by: De Yun Wang

References

- 1. Compalati E, Passalacqua G, Bonini M, Canonica GW. The efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy for house dust mites respiratory allergy: results of a GA2LEN meta‐analysis. Allergy 2009;64:1570–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eifan AO, Calderon MA, Durham SR. Allergen immunotherapy for house dust mite: clinical efficacy and immunological mechanisms in allergic rhinitis and asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2013;13:1543–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Calderon MA, Casale TB, Nelson HS, Demoly P. An evidence‐based analysis of house dust mite allergen immunotherapy: a call for more rigorous clinical studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:1322–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moingeon P. Progress in the development of specific immunotherapies for house dust mite allergies. Expert Rev Vaccines 2014;13:1463–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nelson HS. Update on house dust mite immunotherapy: are more studies needed? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;14:542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calderón MA, Kleine‐Tebbe J, Linneberg A, De Blay F, Hernandez Fernandez de Rojas D, Virchow JC et al. House dust mite respiratory allergy: an overview of current therapeutic strategies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3:843–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mösges R, Ritter B, Kayoko G, Allekotte S. Carbamylated monomeric allergoids as a therapeutic option for sublingual immunotherapy of dust mite‐ and grass pollen‐induced allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: a systematic review of published trials with a meta‐analysis of treatment using Lais® tablets. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panon Adriat 2010;19:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canonica GW, Cox L, Pawankar R, Baena‐Cagnani CE, Blaiss M, Bonini S et al. Sublingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization position paper 2013 update. World Allergy Organ J 2014;7:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Riechelmann H, Epple B, Gropper G. Comparison of conjunctival and nasal provocation test in allergic rhinitis to house dust mite. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2003;130:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anantasit N, Vilaiyuk S, Kamchaisatian W, Supakornthanasarn W, Sasisakulporn C, Teawsomboonkit W et al. Comparison of conjunctival and nasal provocation tests in allergic rhinitis children with Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus sensitization. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2013;31:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. December 2012 update of the NHLBI/WHO Workshop Report 1995. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/documents/5/documents_variants/37.

- 12. Di Gioacchino M, Cavallucci E, Ballone E, Cervone M, Di Rocco P, Piunti E et al. Dose‐dependent clinical and immunological efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with mite monomeric allergoid. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2012;25:671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Astvatsatourov A, Mösges R. Euclidean norm in composite severity score to evaluate an allergic reaction from conjunctival provocations. J Health Med Inform 2014;05:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dogan S, Astvatsatourov A, Deserno TM, Bock F, Shah‐Hosseini K, Michels A et al. Objectifying the conjunctival provocation test: photography‐based rating and digital analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2014;163:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Declaration of Helsinki, Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 59th WMA General Assembly, Seoul, 107 (2008). [PubMed]

- 16. ICH . ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: Guideline for good clinical practice E6 (R1) 1996. [PubMed]

- 17. Passalacqua G, Albano M, Fregonese L, Riccio A, Pronzato C, Mela GS et al. Randomised controlled trial of local allergoid immunotherapy on allergic inflammation in mite‐induced rhinoconjunctivitis. Lancet 1998;351:629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Passalacqua G, Pasquali M, Ariano R, Lombardi C, Giardini A, Baiardini I et al. Randomized double‐blind controlled study with sublingual carbamylated allergoid immunotherapy in mild rhinitis due to mites. Allergy 2006;61:849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bergmann K‐C, Demoly P, Worm M, Fokkens WJ, Carrillo T, Tabar AI et al. Efficacy and safety of sublingual tablets of house dust mite allergen extracts in adults with allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;133:1608–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mösges R, Pasch N, Schlierenkämper U, Lehmacher W. Comparison of the biological activity of the most common sublingual allergen solutions made by two European manufacturers. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2006;139:325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klimek L, Willers J, Hammann‐Haenni A, Pfaar O, Stocker H, Mueller P et al. Assessment of clinical efficacy of CYT003‐QbG10 in patients with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: a phase IIb study. Clin Exp Allergy 2011;41:1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klimek L, Schendzielorz P, Pinol R, Pfaar O. Specific subcutaneous immunotherapy with recombinant grass pollen allergens: first randomized dose‐ranging safety study. Clin Exp Allergy 2012;42:936–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Riechelmann H, Schmutzhard J, van der Werf JF, Distler A, Kleinjans HA. Efficacy and safety of a glutaraldehyde‐modified house dust mite extract in allergic rhinitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2010;24:e104–e109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Astvatsatourov A, Gloistein C, Mösges R. Imaging Analysis of Conjunctival Provocation in Patients on Placebo. In: Poster. EAACI Barcelona 2015.

- 25. Lombardi C, Gargioni S, Melchiorre A, Tiri A, Falagiani P, Canonica GW et al. Safety of sublingual immunotherapy with monomeric allergoid in adults: multicenter post‐marketing surveillance study. Allergy 2001;56:989–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. La Grutta S, Arena A, D'Anneo WR, Gammeri E, Leonardi S, Trimarchi A et al. Evaluation of the antiinflammatory and clinical effects of sublingual immunotherapy with carbamylated allergoid in allergic asthma with or without rhinitis. A 12‐month perspective randomized, controlled, trial. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;39:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marogna M, Colombo F, Cerra C, Bruno M, Massolo A, Canonica GW et al. The clinical efficacy of a sublingual monomeric allergoid at different maintenance doses: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2010;23:937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scalone G, Compalati E, Bruno ME, Mistrello G. Effect of two doses of carbamylated allergoid extract of dust mite on nasal reactivity. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;45:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mosbech H, Canonica GW, Backer V, de Blay F, Klimek L, Broge L et al. SQ house dust mite sublingually administered immunotherapy tablet (ALK) improves allergic rhinitis in patients with house dust mite allergic asthma and rhinitis symptoms. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;114:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Casale TB, Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Cox L, Lockey R, Nelson HS et al. Recommendations for appropriate sublingual immunotherapy clinical trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bousquet J, Schünemann HJ, Bousquet PJ, Bachert C, Canonica GW, Casale TB et al. How to design and evaluate randomized controlled trials in immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis: an ARIA‐GA(2) LEN statement. Allergy 2011;66:765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]