Abstract

Aim:

To assess the epidemiology, pattern, and outcome of trauma in pediatric population.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 1148 pediatric patients below 15 years of age presenting in the emergency department of our hospital were studied over a period of 3 years. The patients were categorized into four age groups of <1 year, 1–5 years, 6–10 years, and 11–15 years. The data were compared regarding mode of trauma, type of injury, place of injury among different age groups and both sexes.

Results:

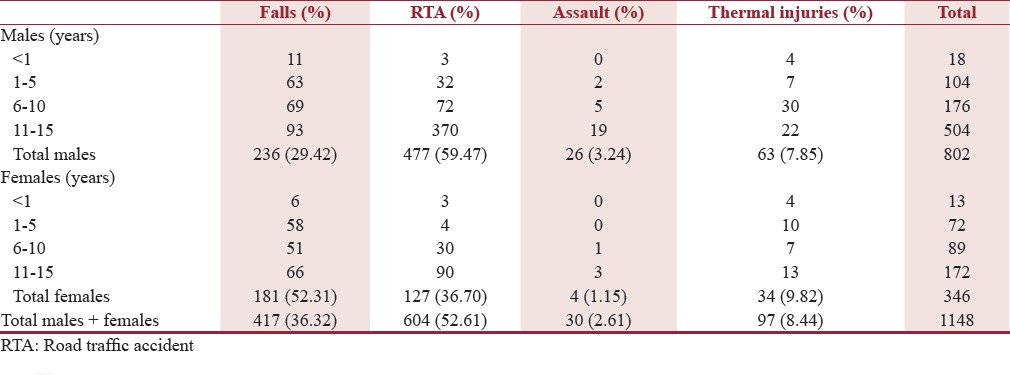

The majority of the pediatric trauma cases were seen in males 69.86%, (n = 802) and females comprised only 30.13% (n = 346). Road traffic accident (RTA) was the most common mode of trauma in male children, i.e. 59.47% (n = 477) followed by fall injuries, i.e. 29.42% (n = 236). In females, fall was the most common mode of trauma, i.e. 52.31% (n = 181) followed by RTA (36.70%, n = 127). Fall injuries occurred mostly at homes. Among RTA, hit by vehicle on road while playing was most common followed by passenger accidents on two wheelers, followed by hit by vehicle while walking to school. Among fall, fall while playing at home was the most common. Out of total 1148 patients, 304 (26.48%) comprised the polytrauma cases (involvement of more than two organ systems), followed by abdominal/pelvic trauma (20.99%, n = 241), followed by head/face trauma (19.86%, n = 228). Out of total 1148 patients admitted over a period of 36 months, 64 died (5.57%). 75 (6.5%) patients had some kind of residual deformity or disability.

Conclusion:

The high incidence of pediatric trauma on roads and falls indicate the need for more supervision during playing and identification of specific risk factors for these injuries in our setting. This study shows that these epidemiological parameters could be a useful tool to identify burden and research priorities for specific type of injuries. A comprehensive trauma registry in our set up seems to be important for formulating policies to reduce pediatric trauma burden.

KEY WORDS: Fall-related injuries, pediatric trauma, polytrauma, road traffic accidents

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, substantial reduction in child mortality has occurred worldwide due to continuous and sustained efforts. Most of these initiatives have focused on reducing the burden of communicable diseases. At the same time, it is also becoming apparent that children saved from these diseases are becoming victims of trauma on roads, streets, play areas, or at home.

Pediatric injuries are the major cause of mortality and disability worldwide and accounts for a significant burden on countries with limited resources.[1] About 5 million children die from trauma each year.[2] Trauma is the leading cause of death in this age group in the United States greater than all other diseases combined. National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) data reveals the nearly 15–20% of trauma deaths occur among children. As per NCRB report of 2006, there were approximately 22,000 deaths in <14 years age group due to injuries. There are very few studies from developing nations describing the prevalence and potential risk factors of pediatric trauma. The detailed analysis of epidemiology of the pediatric trauma can give possible insight into its prevention and intervention at initial level to decrease the disability resulting from pediatric injuries.[3]

This study is an attempt to describe the pattern of trauma, type of injuries, and epidemiology among pediatric population. As trauma burden, pattern, mode of injury, site of injury, and outcome varies from region to region and also in different age groups, it is essential to understand these characteristics to formulate effective injury prevention strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a prospective study conducted at a tertiary hospital over a period of 36 months. A total of 1148 patients up to 15 years old with a history of trauma between July 2013 and June 2016 were included in this study. The complete spectrum of pediatric trauma was included in this study. Exclusion criteria included cases of sexual assault, poisoning, drowning, and patients with psychiatric disorders presenting with trauma. We prospectively collected the data from all trauma patients using a standard pro forma in the emergency department of our hospital. For each pediatric trauma patient, we collected detailed demographic information, gender, site of injury, mode of injury, place of injury, nature of injury, any intervention required, and final outcome of the trauma. Parental consent was sought from all the patients. Detailed history taking and examination of all the pediatric trauma patients was done.

RESULTS

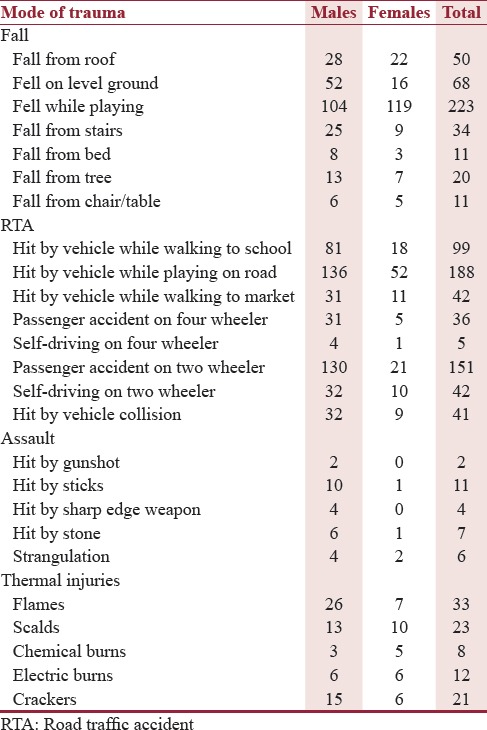

During the total study of 36 months, 1148 patients reported to us in the emergency ward. Pediatric patients till the age of 15 years were included in the study. Patients of sexual assault, poisoning, drowning cases and patients of psychiatric disorders with trauma were not included in the study. The age and gender distribution of trauma-related pediatric cases were assessed according to four categories: <1 year, 1–5 years, 6–10 years, and 11–15 years. The majority of the pediatric trauma cases were seen in males (69.86%, n = 802) and females comprised only 30.13% (n = 346) [Table 1]. The present study also revealed that 11–15 years comprised the most common age group involved in pediatric trauma. Road traffic accidents (RTA) were the most common mode of trauma in male (59.47%, n = 477) followed by falls (29.42%, n = 236), followed by assaults and thermal injuries [Table 2]. In contrast to males, fall was the most common mode of trauma in females patients followed by RTA and thermal injuries and assaults [Table 2]. Among the RTA patients, hit by vehicle while playing on roads (136/604) was the most common followed by passenger accidents on two wheelers (130/604) [Table 3]. Hit by vehicle while going to school as pedestrian comprised the third common mode among the RTA patients (81/604). There were cases of self-driving on two wheelers, i.e. 42/604 by children aged between 10 and 15 years [Table 3]. Similarly, 5/604 children had trauma while self-driving four wheeler. 36.32% (n = 417/1148) of patients were affected by fall, second most common mode of trauma overall and first most common mode of trauma in females. Among pediatric fall patients, fall while playing at home/play area comprised the most common mode followed by fall on ground, fall from roof and fall from stairs, fall from bed, fall from tree, fall from chair/table least common [Table 3]. Overall in both males and females, thermal injuries comprised the third most common mode of injury (8.44%, n = 97). Scalds and flames injuries were more common in <5 years age group, and cracker burns were exclusively seen in elder children only during festive season. Electric and chemical burns were uniformly distributed among different age groups.

Table 1.

Gender distribution among different age groups

Table 2.

Different modes of trauma among different age groups and gender

Table 3.

Mode of trauma and type of trauma among different age groups

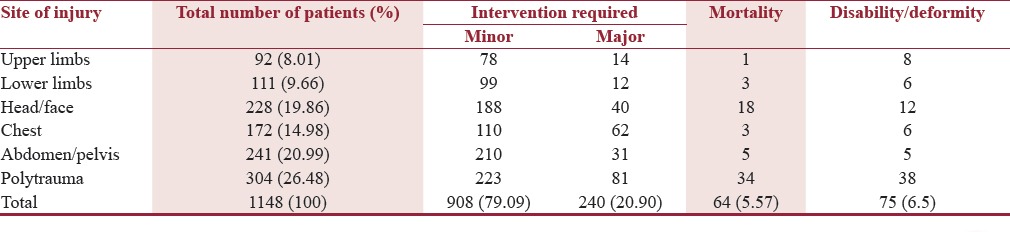

Out of total 1148 patients, 304 (26.48%) comprised the polytrauma cases (involvement of more than two organ systems), followed by abdominal/pelvic trauma (20.99%, n = 241), followed by head/face trauma (19.86%, n = 228). Isolated chest trauma comprised only 14.98% (n = 172). Upper limb and lower limb injuries comprised the least common anatomic sites of injuries [Table 4].

Table 4.

Anatomic site of trauma with intervention required and associated mortality and disability

Out of total 1148 patients admitted over a period of 36 months, 64 died (5.57%). 75 (6.5%) patients had some kind of residual deformity or disability.

DISCUSSION

Trauma is defined as any physical damage to the body resulting from abrupt exposure to forces exceeding the tolerance level, or the lack of warmth or oxygen. It usually occurs under foreseeable circumstances, so it is very important to recognize those settings where preventive measures could be implemented. Being able to identify such circumstances help to implement prevention strategies, which are more cost-effective than a late intervention. Trauma injuries are the main cause of morbidity and mortality among children and adolescent both in developed and developing countries. Accidental injuries of pediatric population are on the rise and have become an important social problem.[3,4] Injuries account for about 12% of the disease burden worldwide and place a disproportionate burden on countries with limited resources.[5] In 2004, over 9.5 lakh children under 18 years died as a result of injuries.[6] Many children who survive trauma may develop a temporary or permanent disability, requiring continuing care and has a significant impact on their psychosocial health and financial burden. Although many studies are conducted on the epidemiology of pediatric trauma, to our knowledge this study represents the initial description regarding predisposing factors, circumstances leading to trauma, different age groups of both sex, different type and mode of trauma with anatomic site of injuries which helps us in working on preventive factors to reduce the pediatric trauma and associated morbidity and mortality.

The present study revealed that males are more commonly injured than females. 69.86% of patients in our study were males as compared to 30.13% of females. There could be several possible explanations for these findings. Male children are given more freedom, opportunities, and facilities than females in all aspects in our society. Likewise, they are more exposed to potential risk factors and potential environment suitable for trauma such as playing on roads, rooftop, on trees, or near construction sites. The cultural role of males as bread earners could also be responsible for increased likelihood of being exposed to potentially risky environment.[7] Kulshrestha et al., Sharma et al., Verma et al. have also found boys to be more commonly involved than girls.[8,9,10] Overall RTA was found to be the most common mode of trauma in our study. Unlike, previous study by Bangdiwala et al., where home was the most common place of injury,[11] 52.61% of our patients presented with RTA irrespective of sex followed by falls-related injuries (36.32%), both at home and outside environment. This was followed by thermal injuries (8.44%) and assault in only 2.61% in both sexes. Detailed analysis of the mode of trauma in different age groups revealed that RTA was the most common 11–15 years age group followed by 6–10 years age group. Further, the study also revealed that RTA was much more common in boys (59.47%) than girls (36.70%).

Fall-related injuries were more common in girls (52.31%) than boys (29.42%). Most of the small children were injured while playing, whereas younger children were injured during work activities. Among the fall-related injuries in our setting, significant no of patients had fallen from roof during kite flying festival season. Fractures and concussions were commonly observed. Study of Sharma et al. revealed that falls were the leading cause of trauma in all age groups, followed by RTA.[12] Similarly, study by Hyder et al. documented that an average of 36% of all injuries was done due to falls in children <5 years of age with Africa having an incidence rate of 786/1.0 lakh.[13] Similar study in Nepal reported that falls were reported as the most common injury, occurring in 65% of study participation.[14]

Among the total of fall-related injuries of 417 children, 223 had fallen while playing both at home n outside followed by fall on ground and fall from roof and tree. This could be explained by the lack of safety measures in unsupervised kids. Fall from bed was seen most commonly in infants of both sexes in 11 patients. Sharma et al. also revealed that stairs and terrace were the most common causes of fall from height.[12] These findings signify different epidemiological patterns in different parts of the world. Out of total of 604 patients of RTA, hit by vehicle while playing on road in 188 patients followed by 151 had passenger accidents on two wheelers closely followed by hit by vehicle while walking to school in 99 patients. Alarming figures came out regarding self-driving on two wheelers, i.e. 42/604 by children aged between 10 and 15 years. Similarly, 5/604 children had trauma while self-driving four wheeler. Passenger accidents on four-wheeler and hit by vehicle while walking to market had almost equal numbers of 41 and 42, respectively. In a study by Sharma et al. revealed that most of victims of RTAs were pedestrians, followed by two wheelers. The results of these studies were similar to studies from Iran and Mozambique.[15,16]

Among the total 30 patients of assault, 11 were hit by sticks, 7 by stones on head, 6 were strangulated 4 by sharp-edged weapons, and 2 by unintentional gunshots.

In this study, out of a total of 97 patients of thermal injuries, flame burns (33), scalds (23), cracker burns (21), electric burns (12), and chemical burns (8) were seen. Approximately, about 60% of thermal burns were seen in boys compared to girls (40%). Contrary to our study, Ahmad concluded that hot liquids injuries were more common than flame burns.[17] Parbhoo et al. also reported the similar results.[18]

In this study of anatomical site of injury, out of a total of 1148 patients, 26.48% had polytrauma, 20.99% had abdominal and pelvic injuries, 19.86% had head/face injuries, 14.98% had chest injuries followed by upper and lower limb injuries. Around (908) 80% of patients required minor interventions and only (240) 20% children required major intervention (required intubation). Our study had a mortality rate of 5.57% (n = 64). Our study had similar finding as that by Ameh and Mshelbwala[19] However, the study by Simon et al. had a mortality rate of 12.7% which is significantly higher than other researchers.[20] Most mortality in this study occurred in polytrauma patients followed by head trauma patients. Mortality was higher in boys compared to girls. RTA was the most common cause of death, followed by falls-related injuries. Our findings were similar to studies conducted by Adesunkanmi and Oyelami[21] Disability was seen in 6.5% of pediatric injury patients.

Factors predisposing to pediatric trauma have rarely been investigated and currently there are no injury prevention programs for pediatric population. The high incidence of pediatric trauma on roads and falls indicates the need for more supervision during playing and identification of specific risk factors for these injuries in our setting. School-based programs with cartoons and comics characters should be done on regular basis to educate the children regarding road safety measures. Parents need to be counseled regarding giving either two wheelers or four wheelers to their children only after they reach the legal age of driving. Active participation of children in these programs can keep the momentum up to prevent the pediatric road injuries. Play areas and children parks should be properly walled to prevent injuries. A significant proportion of fall-related injuries in younger children resulted during unsafe work-related activities in our study. Child labor needs to be addressed on an urgent basis, secondly worker safety norms need to be implemented strictly. This study shows that these epidemiological parameters could be useful tool to identify burden and research priorities for specific type of injuries. A more detailed and comprehensive trauma registry in our set up seems to be important for formulating policies to reduce pediatric trauma burden.

There are several limitations that need to be mentioned in our study. First, this study captures the pediatric trauma patients that received attention at the emergency department of our tertiary care institution. It does not include those injuries treated at home or other private health centers, or when our investigator was not present. There is also possibility of selection bias in registering the patients. Patients of drowning and poisoning were not included in the study, as these patients reported to the physician incharge of the emergency department. Their inclusion also might have influenced the study.

CONCLUSION

Factors predisposing to pediatric trauma have rarely been investigated and currently there are no injury prevention programs for pediatric population. This study shows that these epidemiological parameters could be useful tool to identify burden and research priorities for specific type of injuries. A more detailed and comprehensive trauma registry in our set up seems to be important for formulating policies to reduce pediatric trauma burden.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO/UNICEF. Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention: A Global Call to Action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2005. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43279/1/9241593415_eng.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holder Y, Peden M, Krug E, Lund J, Gururaj G, Kobusingye O. Injury Survelliance Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/media/en/136.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatamabadi HR, Mahfoozpour S, Alimohammadi H, Younesian S. Evaluation of factors influencing knowledge and attitudes of mothers with preschool children regarding their adoption of preventive measures for home injuries referred to academic emergency centres, Tehran, Iran. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:252–9. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2013.816325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatamabadi H, Mahfoozpour S, Forouzanfar M, Khazaei A, Yousefian S, Younesian S. Evaluation of parameter related to preventative measures on the child injuries at home. J Saf Promot Inj Prev. 2013;1:140–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molcho M, Walsh S, Donnelly P, Matos MG, Pickett W. Trend in injury-related mortality and morbidity among adolescents across 30 countries from 2002 to 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(Suppl 2):33–6. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peden M, McGee K, Sharma G. The Injury Chart book: A Graphical Overview of the Global Burden of Injuries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42566/1/924156220X.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peden M, Oyegbite K, Ozanne-Smith J, Hyder AA, Christine B, Rahman AK, et al. World Report on Child Injury Prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/eapro/World_report.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulshrestha R, Gaind BN, Talukdar B, Chawla D. Trauma in childhood – past and future. Indian J Pediatr. 1983;50:247–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02752757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma AK, Sarin YK, Manocha S, Agarwal LD, Shukla AK, Zaffar M, et al. Pattern of childhood trauma. Indian perspective. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma S, Lal N, Lodha R, Murmu L. Childhood trauma profile at a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:168–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bangdiwala SI, Anzola-Pérez E, Romer CC, Schmidt B, Valdez-Lazo F, Toro J, et al. The incidence of injuries in young people: I. Methodology and results of a collaborative study in Brazil, Chile, Cuba and Venezuela. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:115–24. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma M, Lahoti BK, Khandelwal G, Mathur RK, Sharma SS, Laddha A. Epidemiological trends of pediatric trauma: A single-center study of 791 patients. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2011;16:88–92. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.83484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyder AA, Sugerman D, Ameratunga S, Callaghan JA. Falls among children in the developing world: A gap in child health burden estimations? Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:1394–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poudel-Tandukar K, Nakahara S, Ichikawa M, Poudel KC, Joshi AB, Wakai S. Unintentional injuries among school adolescents in Kathmandu, Nepal: A descriptive study. Public Health. 2006;120:641–9. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karbakhsh M, Zargar M, Zarei MR, Khaji A. Childhood injuries in Tehran: A review of 1281 cases. Turk J Pediatr. 2008;50:317–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Sousa Petersburgo D, Keyes CE, Wright DW, Click LA, Macleod JB, Sasser SM. The epidemiology of childhood injury in Maputo, Mozambique. Int J Emerg Med. 2010;3:157–63. doi: 10.1007/s12245-010-0182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad M. Pakistani experience of childhood burns in a private setup. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2010;23:25–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parbhoo A, Louw QA, Grimmer-Somers K. A profile of hospital-admitted paediatric burns patients in South Africa. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:165. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ameh EA, Mshelbwala PM. Challenges of managing paediatric abdominal trauma in a Nigerian setting. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2007;2:90–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon R, Gilyoma JM, Dass RM, Mchembe MD, Chalya PL. Paediatric injuries at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania: A prospective review of 150 cases. J Trauma Manage Outcomes. 2013;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adesunkanmi K, Oyelami OA. The pattern and outcome of burn injuries at Wesley Guild Hospital, Ilesha, Nigeria: A review of 156 cases. J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;97:108–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]