Abstract

Material stability and dissolution in aqueous media are key issues to address in the development of a new nanomaterial intended for technological application. Dissolution phenomena affect biological and environmental persistence; fate, transport, and biokinetics; device and product stability; and toxicity pathways and mechanisms. This article shows that MoS2 nanosheets are thermodynamically and kinetically unstable to O2-oxidation under ambient conditions in a vareity of aqueous media. The oxidation is accompanied by nanosheet degradation and release of soluble molybdenum and sulfur species, and generates protons that can colloidally destabilize the remaining sheets. The oxidation kinetics are pH-dependent, and a kinetic law is developed for use in biokinetic and environmental fate modelling. MoS2 nanosheets fabricated by chemical exfoliation with n-butyl-lithium are a mixture of 1T (primary) and 2H (secondary) phases and oxidize rapidly with a typical half-life of 1–30 days. Ultrasonically exfoliated sheets are in pure 2H phase, and oxidize much more slowly. Cytotoxicity experiments on MoS2 nanosheets and molybdate ion controls reveal the relative roles of the nanosheet and soluble fractions in the biological response. These results indicate that MoS2 nanosheets will not show long-term persistence in living systems and oxic natural waters, with important implications for biomedical applications and environmental risk.

Keywords: transition metal dichalcogenides, oxidation, dissolution, nanotoxicology

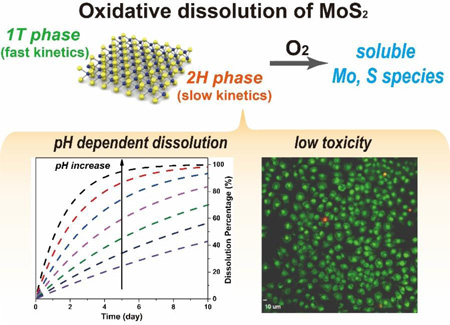

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Environmental stability is one of the most important properties of a newly discovered nanomaterial targeted at large-scale application. Degradation affects the lifetime and reliability of the material and its derived products or devices, and can constrain operating windows and limit application fields. Stability in aqueous phases is of special importance for assessing environmental and health effects, which is a key step in the development pathway, as a new chemical substance moves from the laboratory to large-scale manufacturing and use. Chemical degradation pathways in aqueous phases determine if a new nanomaterial will be persistent upon release into the natural environment with the potential for long-term impacts, or will degrade into molecular species that no longer pose a material-specific or “nano-specific” risk.

In the human body, nanomaterial stability in biological fluid phases affects biopersistence, biokinetics, lung and renal clearance, and the proper design and interpretation of experiments to characterize toxicity. Inorganic materials that degrade typically produce a pool of soluble species that co-exist with the solid in biological media, and can initiate toxicity pathways independently of, or in parallel with, the solid phase.1–9 As free molecular species, these soluble products often act with high bioavailability and molecular specificity at target receptors. Indeed, many nanomaterials are now known to exert their biological effects wholly, or in part, through the action of co-existing ions, with outstanding examples being nanoscale Ag,1, 9–11 ZnO,2, 12, 13 Cu,5, 14 and Ni.6 If left uncharacterized or uncontrolled during sample storage and preparation, these ion pools can lead to varying and confounding toxicity data, or the incorrect interpretations of molecular toxicity mechanisms.4, 15 In contrast, materials that are stable are often not effectively cleared from the lung or from the bloodstream and show long-term bio-persistence that is of concern for the induction of diseases after a long latent period, such as mesothelioma or lung cancer associated with asbestos fiber exposure. Overall, identifying aqueous-phase degradation pathways, kinetics, and products, should be one of the first goals in characterizing a new nanomaterial targeted for large-scale technological application.

Among the most promising next-generation nanomaterials are the 2D transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), which are fabricated in monolayer or few-layer form by colloidal growth, vapor-phase growth, or exfoliation of bulk layered parent crystals.7, 16–23 Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), for example, consists of covalently bonded atomic trilayers of sulfur-molybdenum-sulfur, which in the bulk crystal are stacked with van der Waals gaps that allow exfoliation by a variety of chemical or ultrasonic methods.18, 19, 24, 25 MoS2 has received tremendous attention because its monolayer form exhibits a direct band gap, while the bulk form exhibits only an indirect band gap.26 Exfoliation thus induces an indirect-to-direct conversion with a remarkable enhancement of light absorption efficiency and promising applications in electronics and optoelectronics.19, 27–30

We became interested in the stability and degradation of TMD materials as a logical early step in the understanding of their biological and environmental behaviors. Traditionally TMDs are regarded as quite stable materials because of the lack of dangling bonds in the electron-filled shells of terminating chalcogen atoms.31 MoS2 is listed as “water insoluble” in standard chemical reference works,32 and has been reported in many studies to be stable to oxidation under ambient conditions.33–35 Recent modelling results suggest that the ambient stability of MoS2 is due to kinetic limitations associated with the initial dissociative adsorption of O2 on MoS2 surfaces.34

Under more extreme conditions, far from ambient, oxidation of TMD nanosheets has been well documented.36, 37 Yamamoto et al. reported the formation of molybdenum oxide (MoO3) on an atomically thin MoS2 surface after exposure to oxygen at temperatures above 340 °C, and demonstrated that the oxidation starts at MoS2 defects sites.36 At a comparable temperature, WSe2 nanosheets were observed to form WO3 initiating from the nanosheet edge and propagating inward. The reaction rate decreased with decreasing temperature and became negligible below 200 °C.37 While it is clear that MoS2 does not oxidize readily in ambient air, a recent study focused on long-term effects documented degradation over time scales of six months to one year, and discussed its important implications for electronic applications.38 Also relevant is an older report on formation of a passivating oxide layer on the surface of bulk MoS2, which prevents stoichiometric (full) conversion to the oxide in the dry state.35 There are also chalcogen-based 0D nanoparticles such as CdSe quantum dots (QDs), and studies have shown quenching and chemical degradation during their use under physiologic conditions, which was ascribed to chemical oxidation of sulfur or selenium atoms on the QD surface.39, 40

Despite the importance of MoS2, we were not able to find any studies relating to the long-term stability or persistence of MoS2 in aqueous phases relevant to biological systems or the natural environment. A recent review article presented a thermodynamic analysis suggesting that MoS2 and other TMD nanosheet materials would be unstable to oxidative dissolution in O2-containing aqueous media, but no data were available to reveal if the kinetics are sufficiently fast for measureable degradation over relevant time scales.7 If strong oxidizing agents such as hydroxyl radicals or H2O2 are introduced, then etching of MoS2 is indeed observed and leads to formation of MoS2 quantum dots and soluble molybdenum species,41 but of course these data are not directly relevant to the reaction with O2 as the sole oxidant.

We therefore undertook a systematic study of the long-term stability and oxidative dissolution of MoS2 nanosheets in biologically and environmentally relevant aqueous media with and without dissolved molecular oxygen. It will be shown that MoS2 nanosheets undergo a clear O2-driven oxidative dissolution process with kinetics that depend on pH, exfoliation method, phase, and processing history with important implications for environmental health and safety.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of 2D MoS2 nanosheets

A dispersion of MoS2 nanosheets was prepared by organolithium intercalation followed by forced hydration19 and referred to here as “chemically exfoliated MoS2” (ce-MoS2). Ultrasonically exfoliated nanosheets (ue-MoS2) were produced with a surfactant-assisted exfoliation similar as that developed by Smith et al.18 Excess surfactant (sodium cholate) was removed by ultrafiltration using Amicon centrifugal ultrafilter (Ultra-15, 3K). The conversion of 1T component in ce-MoS2 to 2H phase was carried out in hydrothermal reaction.42 Specially, 10 mL of ce-MoS2 (50 ppm of Mo) was added to a 20 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 200 °C for 4 h. A low concentration of ce-MoS2 nanosheet precursor was used to minimize aggregation and its potential effects on the oxidation rate of the converted MoS2 nanosheets. Additional synthesis and characterization details can be found in Supporting Information.

Dissolution of 2D MoS2 nanosheets in aqueous solutions

To investigate the long-term stability of ce-MoS2, dispersion samples at high (~ 210 ppm of Mo), medium (~ 42 ppm of Mo) and low concentration (~ 8.5 ppm of Mo) were prepared and placed under ambient conditions (air exposure, room temperature) for fixed times. To investigate the effect of oxygen, control groups were prepared and the timed incubation was carried out in a nitrogen-filled glovebox. After a pre-determined incubation time, the solids were separated from the dissolved species using centrifugal ultrafiltration43 and the total soluble Mo concentrations determined by ICP-AES (JY 2000 Ultrace). During the dissolution reactions, the dispersion pH was monitored with a pH electrode (Orion 8165BNWP, Thermo Scientific). To investigate the effects of pH on the oxidative dissolution of MoS2 nanosheets, MoS2 nanosheet dispersions (~ 8.5 ppm of Mo) were incubated in various buffer solutions: 50 mM acetate buffers (at pH 3.5 and 5.7), 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8) and 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 10.9) To study media effects, MoS2 dispersions were added to a natural fresh water simulant (50 mM humic acid in acetate buffer, pH 5.7), RPMI 1640 cell culture medium (Sigma 51536C, pH 7.4) and synthetic seawater (Sigma S9148, pH 8.2). After fixed period of time, the dissolved Mo species were isolated and measured by ICP-AES as previously described.

Cell Toxicity Studies

Murine macrophages (ATCC: TIB-67) and human lung epithelial cells (ATCC: HTB-177) were plated into 96 well plates and incubated overnight, then exposed to different concentrations of sodium molybdate (1, 3, 5 or 8 mM) or ce-MoS2 (up to 80 µg/mL) for 24, 48 or 72 hours. Cells were washed once, and then cell viability was assessed after 24, 48 and 72 hours using dehydrogenase activity assay Wst 8 (CCK-8; Dojindo; CK04-05). 10,000 lung epithelial cells or 25,000 macrophages were seeded and exposed, and the cells were washed once with cell culture medium and then exposed to 100 µl/well phenol red-free medium containing WST-8 substrate diluted to a concentration of 1:10 for one hour to lung epithelial cells or for 3 hours to murine macrophages. The absorbance was quantified at 450 nm using a Spectramax M2 (Molecular Devices).

Visualization of cell death in murine macrophages and human lung epithelial cells was conducted using ethidium-homodimer /Syto 10 stain after exposure to sodium molybdate (1, 3, 5 or 8 mM) or ce-MoS2 (up to 80 µg/mL) for 24 hours. Cells were washed once and incubated with 5 µM/ml Syto10/ and 1 µg/ml ethidium homodimer (Invitrogen) in phosphate buffered saline for 5 min (macrophages) or 15 min (lung epithelial cells). Images were visualized using a spinning-disk Olympus confocal fluorescence (Model IX81) motorized inverted research microscope.

Results and Discussion

Preparation and characterization of MoS2 nanosheets

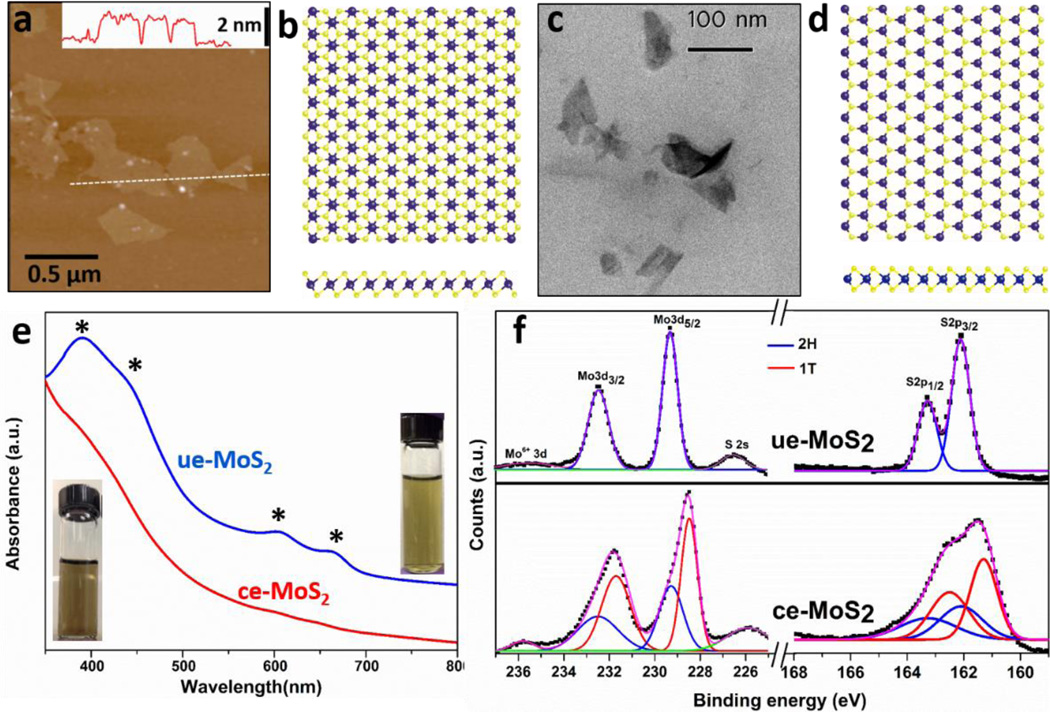

While chemical exfoliation achieves monolayer MoS2 in high yield, the Li intercalation is reported to induce phase changes and alteration of some pristine nanosheet properties.19 Specifically, the organolithium reagent is reported to transfer electrons to MoS2 during the intercalation process to produce negative charges on the nanosheets that can be directly observed in aqueous dispersions by measurement of electrophoretic mobility.44, 45 Lithium intercalation has also been reported to induce structural distortion that converts a fraction of the Mo atoms from trigonal prismatic coordination (the thermodynamically stable and semiconducting 2H phase, Fig. 1d) to octahedral coordination (the metastable metallic 1T phase, Fig. 1b).44, 46 Another widely used fabrication method for 2D MoS2 involves ultrasonic exfoliation using probe sonication.18 The ue-MoS2 nanosheets lack the large negative surface charge but can be colloidally stabilized in aqueous media by the surfactant sodium cholate.18 The ultrasonic method does not typically yield high concentrations of monolayers, but does preserve the naturally occurring 2H phase. Both types of MoS2 nanosheet materials are of interest to the field16, 19, 24, 47–54 and are thus relevant to environmental and health implications studies.55–58 Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) in Fig. 1a reveals as-prepared ce-MoS2 nanosheets with lateral dimension ~ 250 nm, and average thickness ~ 1.2 nm in agreement with the reported values for monolayer MoS2 (see additional AFM images and lateral size distributions in Fig. S1).19, 45 As-prepared ue-MoS2 products are few-layer nanosheets with average lateral size from 100 to 150 nm as shown in Fig. 1c and 2–5 S-Mo-S trilayers (see detailed characterization in Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Structure and crystal phases of MoS2 nanosheets fabricated for this study. (a) AFM image of ce-MoS2 nanosheets, inset: line scan showing the thickness profile along the dash line in the AFM image; (b) atomic positions in the 1T phase with octahedral coordination, (c) STEM image of ue-MoS2 nanosheets, (d) atomic positions in the 2H phase with trigonal prismatic coordination. (e) UV-vis absorbance of ue-MoS2 (blue trace) and ce-MoS2 (red trace) with the characteristic peaks of the 2H phase marked by asterisks. Inset: digital photographs of as-prepared ce-MoS2 (left) and ue-MoS2 (right) dispersions showing uniformity. (f) XPS spectra and deconvolution analysis (Mo 3d and S 2p) showing that ue-MoS2 is in the 2H phase, and ce-MoS2 has mixed 1T and 2H phases.

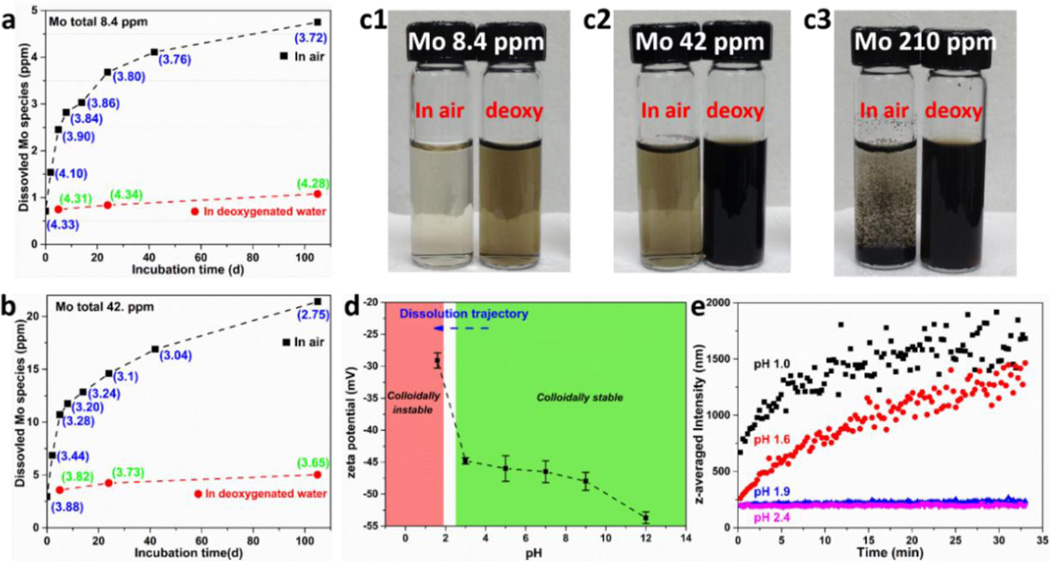

Figure 2.

Oxidative dissolution and colloidal stability of ce-MoS2. Dissolution of ce-MoS2 nanosheets at low (a) and intermediate starting concentration (b) in air-saturated water, but does not occur in deoxygenated water (a,b). This oxidative dissolution process produces protons (pH values given in parentheses), and the pH evolution in (a) and (b) are consistent with the hypothesized oxidation reaction in Eq. 1. (c) Photographs showing that ce-MoS2 is colloidally stable in all dispersions after 105-day incubation except at the highest starting Mo concentrations (210 ppm) in O2-containing water, which produces the highest proton concentrations. This suggests that aggregation of these negatively charged nanosheets is induced by low pH, which is confirmed by the measurements of zeta potentials (d) and hydrodynamic sizes (e) at various pH values. Dynamic light scattering was used to measure the change, and the pH of the solution was adjusted by addition of HCl or NaOH to ce-MoS2 solution (~10 ppm of Mo). Higher resolution view of DLS measurement at pH~2 region can be found in the Supporting Information, Fig. S4.

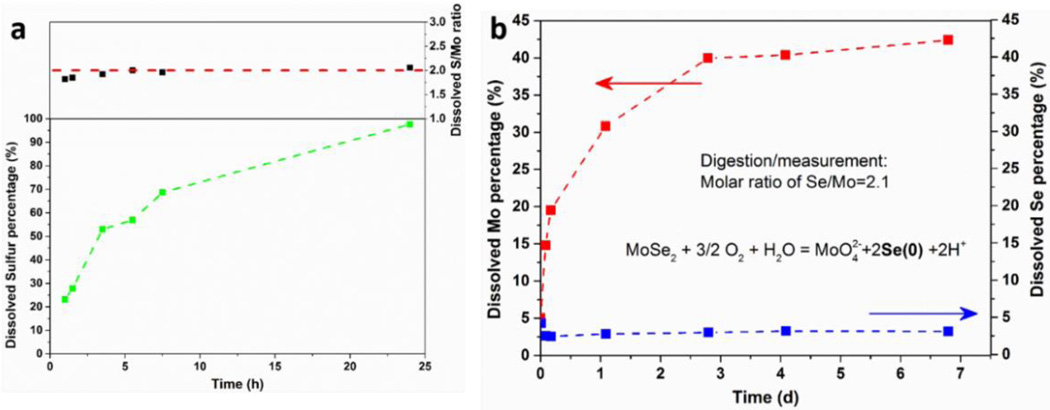

Figure 5.

Analysis of secondary reaction products in the oxidative dissolution of MoS2 and MoSe2. (a) Time-resolved appearance of soluble sulfur species when ce-MoS2 sample is incubated in pH 12 solution. The ratio of S/Mo in the filtrate is close to 2, suggesting uniform degradation of MoS2 and release of all soluble products. (b) As a comparison, ce-MoSe2 can also undergo oxidative dissolution (pH 7.4) releasing soluble Mo, but the chalcogen product is presumably insoluble Se(0).

Due to the differences in electronic structures, ce-MoS2 and ue-MoS2 samples can be differentiated easily by UV-vis spectroscopy. Fig. 1e shows that few-layer ue-MoS2 nanosheets display absorption bands at ~390, 440, 610 and 670 nm (blue trace), consistent with values reported for the 2H phase,19, 42 while ce-MoS2 spectra are nearly featureless. Further, semi-quantitative analysis of the phase composition was carried out using XPS, and the Mo 3d and S 2p regions are shown in Fig. 1f for both types of MoS2 nanosheets. The Mo 3d spectrum of the ue-MoS2 sample consists of peaks at ~ 229.3 and 232.4 eV, which correspond to Mo4+ 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 components of the 2H phase confirming that the ultrasonic exfoliation process does not alter the pristine 2H polymorph. In the ce-MoS2 sample, however, the overall peaks are shifted to lower binding energies and deconvolution reveals the presence of 2H phase peaks and the emergence of additional peaks at lower binding energies, which arise from 1T phase.19, 42 The difference of these two phases in binding energies has been reported to be ~ 0.7 to 0.9 eV.19, 42 Similarly, in the S 2p region, ue-MoS2 shows only the 2H component with doublet peaks S 2p1/2 and 2p3/2, at ~163.2 and 162.1 eV, respectively. Meanwhile additional peaks are also found in the ce-MoS2 sample at the positions ~ 0.8 eV lower with respect to 2H phase peaks. Quantification using the 1T and 2H polymorph spectral fits gives ~61% 1T phase and ~59% 2H phase in the as-prepared ce-MoS2.

Oxidative dissolution and colloidal stability of ce-MoS2 nanosheets

Wang et al.7 showed recently that a range of TMD materials are thermodynamically unstable to oxidative dissolution in simple air-saturated aqueous phases at standard state and fixed pH. We first examine a wider range of conditions for MoS2 and MoSe2 using the approach of Chen and Wang,59 and found that MoS2 and MoSe2 are both thermodynamically unstable to air oxidation over a wide range of pH and concentrations relevant to biological and environmental compartments (see Supporting Information, Table S1 and Figure S2 for details).

In the following, we use centrifugal ultrafiltration and ICP-AES analysis to directly track the time-resolved release of soluble species from ce-MoS2 nanosheets and the time evolution of pH in both oxidizing and non-oxidizing aqueous environments. Figure 2a shows the concentration of soluble Mo species increasing steadily over time in air-saturated water, reaching ~50% of the total Mo in the sample after ~100 days. The dissolution process is suppressed in deoxygenated water (Fig. 2a, red trace), and the finite concentration of soluble Mo that is present at zero time likely reflects some pre-oxidation in the sample preparation and storage. In air-saturated water the pH decreases continuously indicating proton generation in the oxidation process, and the pH decrease is more pronounced at higher initial mass loadings of ce-MoS2 (Fig. 2b). After 105-day incubation, the measured pH values of low and intermediate concentration samples (as shown in Fig. 2a and 2b) agree with anticipated values (3.5 and 2.9, respectively) from the total amount of Mo dissolved based on the reaction stoichiometry:

| (1) |

suggesting that molybdate ion (MoO42−) is the main Mo-containing product. Analysis of other reaction products will be presented in a later section.

Additional experiments were carried out on bulk layered MoS2 powders (~ 2 µm particle size) and the concentration of soluble Mo species was very low and approached the detection limit of ICP-AES even after 40-day incubation.(Supporting Information, Fig. S3) Other studies have shown that bulk MoS2 powders are resistant to oxidation31, 34 or form thin passivating oxide layers that prevent full stoichiometric oxidation under ambient conditions35. Bulk layered MoS2 is described as a stable, insoluble material in a variety of standard references and property databases. Oxidative dissolution over these time scales appears to be a particular behavior of the nanosheet forms of MoS2.

During the dissolution experiments we made the interesting observation that ce-MoS2 nanosheets were colloidally stable in suspensions under all conditions except at the highest mass loading (210 ppm of Mo) after long-term exposure to oxygen in air-saturated water (Fig. 2c). There are relevant reports in the literature of colloidal stability loss in ce-MoS2 nanosheets causing aggregation and restacking during storage.45, 60 It is possible that oxidative or hydrolytic transformation of the MoS2 solid phase is responsible for this loss of colloidal stability, but the patterns in our data suggest it is primarily due to electrostatic destabilization by reaction-generated protons. The colloidal stability of dispersed ce-MoS2 has been attributed to the repulsive forces among negatively charged nanosheets, which arise from the electron transfer from organolithium reagents during intercalation.61 Zeta potential measurements show −45 to −50 mV at neutral pH (Fig. 2d), similar to previous reports45 and suggesting strong electrostatic stabilization initially.62 Fig. 2d shows the pH-dependence of zeta potential, which reaches −28 mV at pH 1.6. This potential is near the typical threshold between electrostatic stabilization and aggregation, and indeed in this range we begin to observe aggregation. To further explore the stability threshold, dynamic light scattering was used to directly monitor the changes in effective nanosheet size (aggregate size) as pH is reduced by HCl addition (Fig. 2e). That transition in ce-MoS2 dispersion occurs near pH 1.9 as indicated by the significant aggregate size growth in Fig. 2e at pH values below 1.9 but not above. Only the ce-MoS2 dispersion with the highest nanosheet mass loading (210 ppm of Mo) and at the greatest extent of oxidation can generate sufficient protons to reach this pH, and only this sample shows the colloidal instability. Overall, these results show that ce-MoS2 nanosheets in aqueous suspensions can undergo aggregation over time, and a sufficient explanation is electrostatic destabilization associated with proton release that is a by-product of the oxidative dissolution process.

Dissolution kinetics and complex media effects

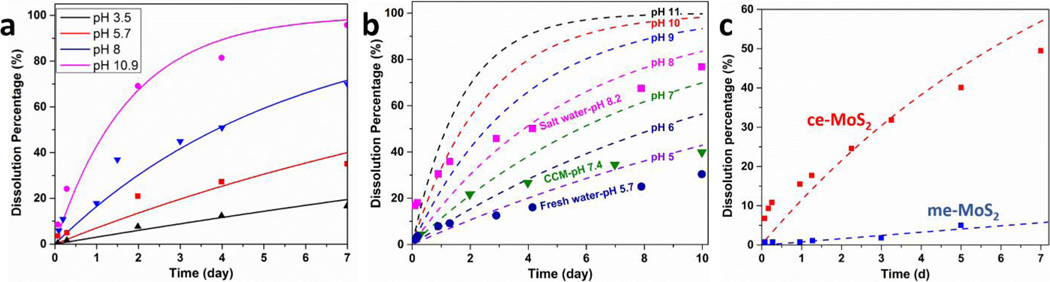

The data from simple media experiments (Fig. 2) are not suitable for quantitative kinetic analysis due to changing pH. We hypothesized that the asymptotic behavior in Fig. 2 is the behavior of a self-limiting reaction that generates protons that inhibit further reaction. We therefore carried out ce-MoS2 dissolution experiments in a range of buffer solutions: acetate buffer (pH 3.5 and 5.7), HEPES buffer (pH 8) and phosphate buffer (pH 10.9). The ionic strengths of the buffers were maintained sufficiently low to minimize nanosheet aggregation during dissolution measurements. The pH-dependent dissolution rates for ce-MoS2 are shown in Fig. 3a, and give the following empirical kinetic equation:

| (2) |

where the rate is expressed in days−1 and OH− is in mol/L units. The fitting is based on the dissolution data at low concentrations of monolayer ce-MoS2, and may be used for the estimation of soluble species release in the low concentration regime most relevant to the environment and other biomedical applications.49, 50 Fig. 3b shows the oxidative dissolution of ce-MoS2 samples in selected simulants of environmental and biological media: natural fresh water (pH 5.7), cell culture medium/CCM (pH 7.4) and sea water (salinity: 3.2% by weight of salt, pH 8.2). These data are superimposed on the pH-dependent rates in simple media (dashed lines), and the comparisons show that the additional media components reduce dissolution rates. This may arise from the aggregation of ce-MoS2 nanosheets in the high ionic strength buffers (sea water and CCM) and/or the presence of reducing agents (humic acid in natural fresh water and thiol functional groups in CCM). The effects are modest, however, and pH appears to be the most important factor influencing ce-MoS2 oxidative dissolution rates.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of pH-dependent oxidative dissolution and complex media effects. (a) pH-dependent dissolution rates obtained using various buffer solutions. The lines show results of an empirical kinetic law (Eq. 2) fit to this data set. (b) Dissolution in complex media (data points) compared to simple media (dash lines, representing model in (a)). (c) Dissolution rates for chemically vs. ultrasonically exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets in HEPES buffers (pH 7). Both undergo continuous dissolution, but the kinetics are much slower for the ue-MoS2 samples.

Figure 3c shows that the ultrasonically exfoliated samples (ue-MoS2) dissolve with much slower kinetics. A possible origin of the slower kinetics in ue-MoS2 is the multilayer nature of this sample, which reflects the lower efficiency of the ultrasonic exfoliation route. We estimate the mean layer number, NL, in ue-MoS2 to be ~ 4 (see Fig. S1), but the difference in mass-specific total area, A, scales as 1/NL and is not sufficient to explain the difference in Fig. 3c. It is also likely that the active sites for oxidative attack on MoS2 reside on edges and basal defects,36 and the edge sites may be expected to retain accessibility in multilayer stacks, so the active site concentration is likely to be even less sensitive to the stacking degree, NL, and cannot fully explain the slow reaction rate for ue-MoS2.

Since surface area cannot explain the kinetic differences between the chemically and ultrasonically exfoliated forms, we considered the effects of solid-state structure. Ue-MoS2 sample consists solely of the stable 2H phase, while the ce-MoS2 samples are mixed 2H / 1T phases and may also contain a higher concentration of defects formed by the violent chemical exfoliation.45, 63 We conducted a series of experiments to explore the role of crystal structure of oxidation kinetics. First, annealing at moderate temperatures has been reported to convert the 1T phase back to the 2H phase.19 Therefore, ce-MoS2 nanosheets were converted to 2H-MoS2 (ce-2H MoS2) in a hydrothermal reaction42 as evidenced by UV-vis characteristic peaks and XPS spectrum in Supporting Information, Fig. S5. The oxidative dissolution of this annealed sample is significantly inhibited relative to the original ce-MoS2 under the same conditions (Fig. S5).

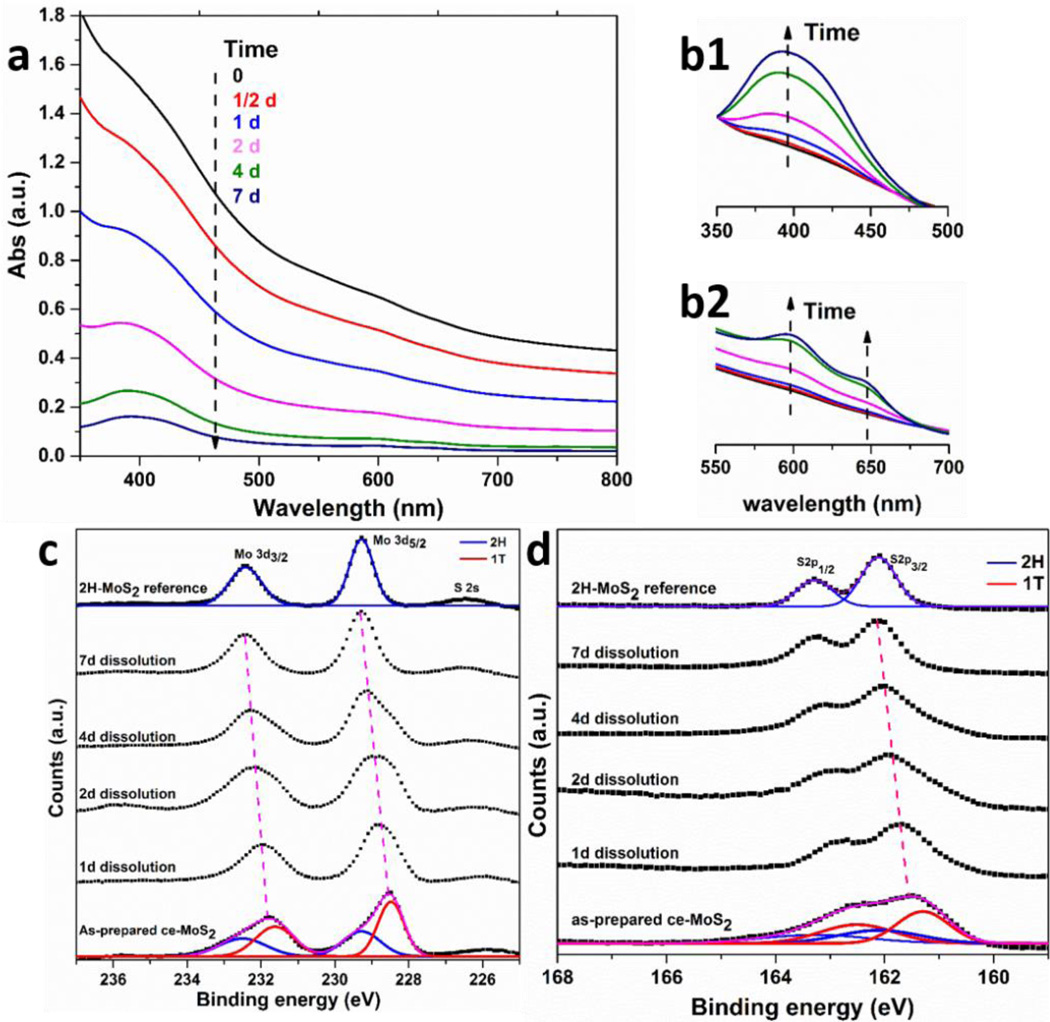

To further investigate the oxidation rate of each component polymorph (1T vs 2H), time-resolved studies were carried out to track the evolution of phase composition of the initially mixed ce-MoS2 samples during oxidation. Selected ce-MoS2 samples were incubated in relatively high pH buffer solution (~ 11.2) to minimize the reaction time needed. Fig. 4a shows, in time-resolved UV-vis spectra of ce-MoS2 dispersion, the absorbance decreases in the entire range from 350 to 800 nm due to the oxidative dissolution of the sample. The characteristic peak of 2H at ~ 400 nm becomes more visible, however, even while the overall peak intensity decreases. Normalizing the spectra by the peak absorbance at ~ 350 (Fig. 4 b1) and ~800 nm (Fig. 4 b2) reveals that the 2H peak undergoes relative growth, which provides further evidence that the 1T component is selectively oxidized to enrich the 2H phase.

Figure 4.

Preferential oxidation of 1T phase over 2H phase. (a) The evolution of UV-vis spectra as a result of oxidative dissolution of ce-MoS2 in high pH buffer (pH ~11.2). The increase of normalized peak intensities at ~ 400 nm (b1, normalized at 350 nm) and ~ 600 to 650 nm (b2, normalized at 800 nm) indicates the preferential oxidation of 1T phase and enrichment of 2H phase. XPS spectra showing Mo 3d (c) and S 2p (d) peak regions for samples treated for different periods of time. The overall convolution peaks are observed to shift to higher binding energies implying the fast decomposition of 1T phase with lower binding energies. 2H phase becomes the only component after 7-day dissolution.

A semi-quantitative analysis is possible using time-resolved XPS spectra. The Mo 3d spectra in Fig. 4c reveal the convolution of 1T and 2H peaks shifted from as-prepared ce-MoS2 to higher binding energies over time, and eventually, after 7-day dissolution, to the position that is typically considered to be pure 2H-MoS2.19 Similar trends can also be observed in the S 2p spectra. The convolution of the peaks from two phases shifts from 161.5 to 162.1 eV. A more apparent feature for the S 2p spectra is the evolution from broad peak contributed by both phases to distinguishable two peaks ascribed to 2H doublets. The XPS results demonstrate that the 1T component in ce-MoS2 is preferentially degraded, leaving only the 2H phase after 7-day of oxidative dissolution. Continuous monitoring on the UV-vis spectra of ce-MoS2 after 7-day exposure reveals further slow decrease, which indicates the 2H may also undergo oxidative dissolution but in a much slower manner, which is consistent with data in Fig. 3c. The ce-MoS2 sample in Fig. 2a was also exposed to air for one full year, after which ICP analysis revealed ~90% of the total molybdenum as soluble species. Some nanosheets remained, however, and showed the characteristic peaks of the 2H phase (Fig. S6). This provides additional evidence for the preferential oxidation of the 1T phase, and the 1-yr persistence in this case reflects the low pH conditions in this experiment (~3) as well as the slow oxidation kinetics of the 2H component that forms the residual solid.

More work is needed to understand the molecular mechanism behind the variable oxidation reactivities observed for different types of MoS2 nanosheets in this study. Higher reactivity correlates here with the presence of the 1T phase, and may be an intrinsic property of that phase associated with its characteristic Mo/S atomic arrangement and metallic nature. Alternatively, the higher reactivity of the ce-MoS2 samples may reflect interaction with the organo-lithium reagent to create defects or negative charge that influence oxidation mechanism. The initiation of oxidative etching via intrinsic defects has been observed in mechanically exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets annealed in oxygen.36

We were also interested in understanding the full reaction products of MoS2 nanosheet oxidation. The biogeochemical literature contains some relevant information on bacterial mediated attack of bulk MoS2 minerals. The general process of mineral bio-oxidation is referred to in this literature as “bioleaching” and can be either direct, or indirect involving a chemical mediator. Mineral oxidation usually occurs through multiple steps catalyzed by either bacterial enzymes or the chemical mediator.64 For MoS2, thiosulfate has been reported to form first, followed by further oxidation by ferric iron in a series of reactions generating soluble intermediate species (S4O62−, HSSSO3−), and finally sulfate.65 Faster oxidative bioleaching of MoS2 was observed in samples of smaller particle size,66 consistent with the expected role of surface area.

To better define the reaction products in the present study, sulfur-based species appearing upon oxidative dissolution of ce-MoS2 were measured by ICP-AES. Fig. 5a shows the percentage of dissolved sulfur species increasing over time until nearly complete dissolution is achieved at ~ 1 day. Again, a high pH buffer was used here to minimize reaction time and to increase the chances of observing any insoluble sulfur intermediates (e.g. sulfur(0), amorphous S) that over longer times may be further oxidized to sulfate. The soluble S/Mo molar ratio is observed to be < 2 in the early stages (possibly suggesting early formation of some insoluble S intermediate), but approaches 2 after 5 hours, indicating eventual conversion of the MoS2 composition to all-soluble species.

Figure 5b shows contrasting behavior for MoSe2 nanosheets prepared by organolithium intercalation and exfoliation. For MoSe2 nanosheets, soluble Mo species (red trace) increase over time in a similar behavior to MoS2, but the chalcogen, Se, does not appear in solution, suggesting the formation of insoluble Se(0). A similar behavior was reported by Zhang et al., who studied the oxidation of Bi2Se3 nanosheets and observed red insoluble amorphous zero-valent selenium as a product that was stable to further oxidation.67

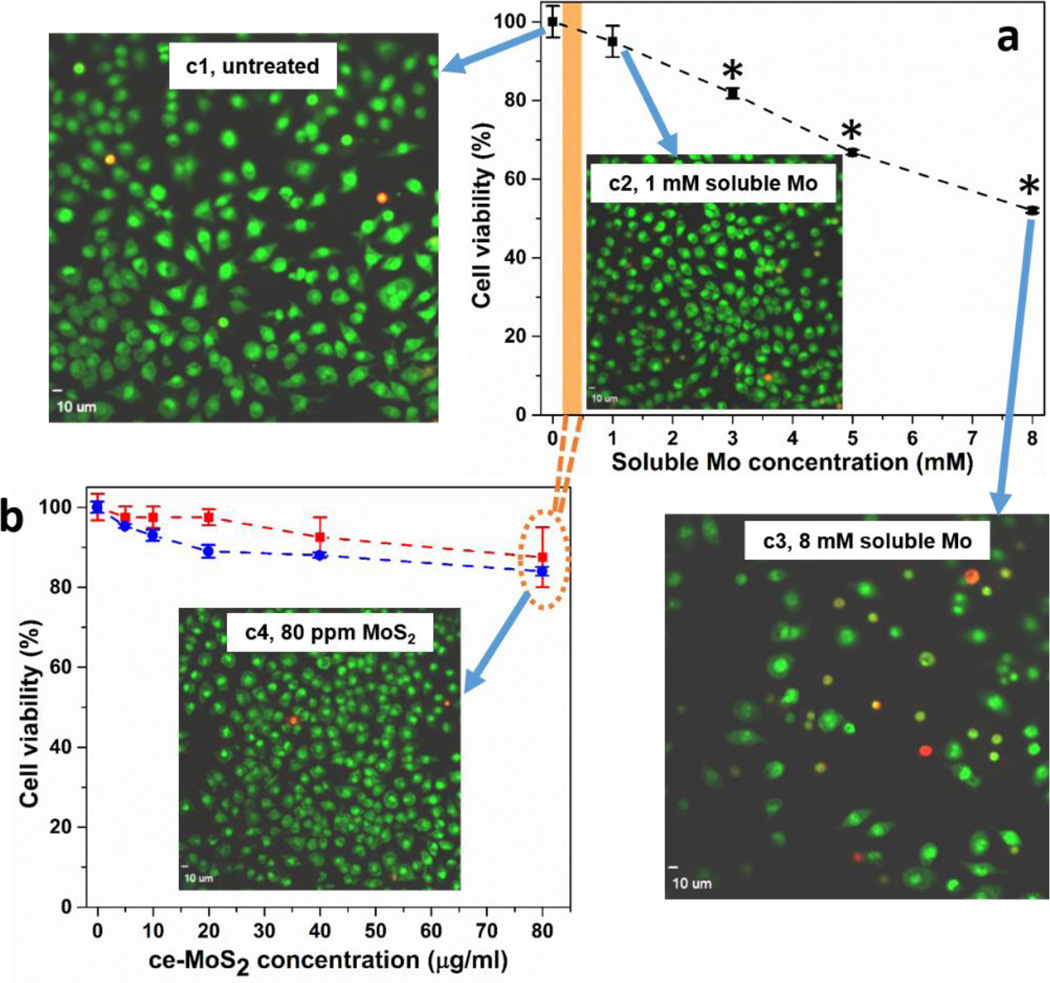

Cytotoxicity of MoS2 nanosheets - implications of ion release

One immediate implication of the present results is the potential for ion release to mediate the biological response to MoS2 nanosheets. Soluble ionic species that coexist with nanoparticles can be highly bioavailable and have been reported to be primary drivers of the cellular response to a number of nanomaterial systems, including ZnO, Ag, Cu and its oxides, Ni and NiO.1, 3, 5, 6, 8–10, 12 The results of Figure 2–5 show that soluble Mo release occurs over time scales of days to weeks at biologically-relevant pH values, which places ce-MoS2 nanosheets in the class of materials that exist as mixed suspensions of soluble ions and solids (nanosheets) during initial exposure, cellular uptake, and processing.

Here we studied the in vitro biological response of murine macrophages and human lung epithelial cells to ce-MoS2 nanosheets. As described previously, both thermodynamics and the observed reaction stoichiometry suggest dissolution products contain molybdate, Mo(VI), so we chose a soluble molybdate salt (Na2MoO4) for the control experiment to understand ion effects. Figure 6b shows that the ce-MoS2 nanosheet samples are not toxic to murine macrophages at doses up to 80 µg/ml. A similar behavior is observed in human lung epithelial cells (Fig. S7). A number of other studies have reported low toxicity for MoS2 nanosheets,56, 58 and they have been proposed for biomedical technologies including drug delivery, photothermal therapy, and imaging.16, 49–51 Soluble molybdate controls show statistically significant cell viability loss at concentrations above 3 mM (Fig. 6a). This Mo concentration, however, is much higher than that achievable during nanosheet exposure, even if the sheets were to undergo complete dissolution (see orange bar that maps soluble Mo concentrations to fnanosheet dose). This comparison helps explain the low toxicity of MoS2 nanosheets observed here and elsewhere - the nanosheets undergo oxidative dissolution, but the released molybdate ions have a low intrinsic toxicity at the material doses commonly used in nanotoxicology studies. Confocal fluorescence imaging demonstrate uptake of ce-MoS2 nanosheets after 24 hours (Figures S7 and S8); there was no apparent degradation after 48 or 72 hours.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity for murine macrophages of ce-MoS2 nanosheets and soluble molybdate ions. Assessment of cell viability after exposure of murine macrophages to different concentrations of Mo salt (a) and ce-MoS2 sample (b). Following exposure to various amounts of Mo salt for 1 d or ce-MoS2 samples for 1 (red trace) or 2 days (blue trace), viability was assessed using dehydrogenase activity assay Wst 8. Concentrations above 3 mM Mo salt caused a significant decrease of viability (*p < 0.05). There was no significant cell death measured within 2 days of treatment in nanosheet samples. Images show visualization of cell death in murine macrophages using ethidium homodimer/Syto 10 stain after exposure to Mo salt or ce-MoS2 nanosheets for 24 hours. Macrophages were seeded into 96 well plates and imaged using an Olympus confocal microscope to visualize live (green) and dead (red) cells. Cells exposed to 8 mM Mo salt (c3) show significant loss in cell count and strong red fluorescence, while unexposed cells (c1), cells exposed to 1 mM Mo salt (c2), 80 µg/ml MoS2 nanosheets (c4) do not show toxicity, shown by strong green fluorescence. Images demonstrating uptake of ce-MoS2 by murine macrophages and human lung epithelial cells can be found in Supporting Information, Fig. S8

Our findings have important implications for environmental health and safety. Chemically exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets undergo a steady oxidative dissolution process in aqueous media over time scales of days to weeks, and are predicted to be non-persistent in living systems and the natural environment. Under the same conditions, bulk MoS2 powders show no measurable dissolution over experimental time frames, highlighting that dissolution is a characteristic behavior of the ultrathin nanosheet form. The oxidative dissolution kinetics depend on media composition, and a pH-dependent kinetic law is developed for use in biokinetic or environmental fate modelling. Ultrasonically exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets, show much slower oxidative dissolution rates, and the difference correlates with crystal phase, which varies from pure 2H in ue-MoS2 to a 1T-rich composition in ce-MoS2. These results are relevant for understanding the role of nanosheet/ion partitioning in the biological response of murine macrophages and human lung epithelial cells. Multiple entry pathways have been described for engineered nanoparticles that vary depending on their size, geometry, and chemical composition, as well as the target cell.68 Depending on the uptake pathway, irregularly-shaped nanoparticles may escape from endosomes and avoid lysosomal compartmentalization and degradation or they may be sorted to lysosomes and rapidly degrade at low pH. A future comprehensive study of uptake mechanisms, compartmentalization, and intracellular degradation in a variety of potential target cells would be important for understanding potential adverse systemic responses following exposure to MoS2 nanosheets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the Superfund Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Superfund Research Grant 2P42 ES013660), and the National Science Foundation (Grant INSPIRE Track 1 CBET-1344097).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional information and figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Liu J, Wang Z, Liu FD, Kane AB, Hurt RH. Chemical Transformations of Nanosilver in Biological Environments. ACS Nano. 2012;6:9887–9899. doi: 10.1021/nn303449n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia T, Kovochich M, Liong M, Mädler L, Gilbert B, Shi H, Yeh JI, Zink JI, Nel AE. Comparison of the Mechanism of Toxicity of Zinc Oxide and Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Based on Dissolution and Oxidative Stress Properties. ACS Nano. 2008;2:2121–2134. doi: 10.1021/nn800511k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nel AE, Mädler L, Velegol D, Xia T, Hoek EM, Somasundaran P, Klaessig F, Castranova V, Thompson M. Understanding Biophysicochemical Interactions at the Nano–Bio Interface. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:543–557. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kittler S, Greulich C, Diendorf J, Koller M, Epple M. Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles Increases During Storage Because of Slow Dissolution under Release of Silver Ions. Chem. Mater. 2010;22:4548–4554. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Von Dem Bussche A, Kabadi PK, Kane AB, Hurt RH. Biological and Environmental Transformations of Copper-Based Nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2013;7:8715–8727. doi: 10.1021/nn403080y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pietruska JR, Liu X, Smith A, McNeil K, Weston P, Zhitkovich A, Hurt R, Kane AB. Bioavailability, Intracellular Mobilization of Nickel, and HIF-1α Activation in Human Lung Epithelial Cells Exposed to Metallic Nickel and Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;124:138–148. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Zhu W, Qiu Y, Yi X, von dem Bussche A, Kane A, Gao H, Koski K, Hurt R. Biological and Environmental Interactions of Emerging Two-Dimensional nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:1750–1780. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00914f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stebounova LV, Guio E, Grassian VH. Silver Nanoparticles in Simulated Biological Media: a Study of Aggregation, Sedimentation, and Dissolution. J. Nanopart. Res. 2011;13:233–244. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Setyawati MI, Yuan X, Xie J, Leong DT. The Influence of Lysosomal Stability of Silver Nanomaterials on their Toxicity to Human Cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35:6707–6715. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peretyazhko TS, Zhang Q, Colvin VL. Size-Controlled Dissolution of Silver Nanoparticles at Neutral and Acidic pH Conditions: Kinetics and Size Changes. Environ. Sci. Techol. 2014;48:11954–11961. doi: 10.1021/es5023202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent RD, Vikesland PJ. Controlled Evaluation of Silver Nanoparticle Dissolution Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Environ. Sci. Techol. 2012;46:6977–6984. doi: 10.1021/es203475a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bian S-W, Mudunkotuwa IA, Rupasinghe T, Grassian VH. Aggregation and Dissolution of 4 nm ZnO Nanoparticles in Aqueous Environments: Influence of pH, Ionic Strength, Size, and Adsorption of Humic Acid. Langmuir. 2011;27:6059–6068. doi: 10.1021/la200570n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setyawati MI, Tay CY, Leong DT. Mechanistic Investigation of the Biological Effects of SiO2, TiO2, and ZnO Nanoparticles on Intestinal Cells. Small. 2015;11:3458–3468. doi: 10.1002/smll.201403232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kent RD, Vikesland PJ. Dissolution and Persistence of Copper-Based Nanomaterials in Undersaturated Solutions with Respect to Cupric Solid Phases. Environ. Sci. Techol. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b04719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiu Z-m, Zhang Q-b, Puppala HL, Colvin VL, Alvarez PJ. Negligible Particle-Specific Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2012;12:4271–4275. doi: 10.1021/nl301934w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Tan C, Zhang H, Wang L. Two-Dimensional Graphene Analogues for Biomedical Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:2681–2701. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00300d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J-K, Pu J, Hsu C-L, Chiu M-H, Juang Z-Y, Chang Y-H, Chang W-H, Iwasa Y, Takenobu T, Li L-J. Large-Area Synthesis of Highly Crystalline WSe2 Monolayers and Device Applications. ACS Nano. 2014;8:923–930. doi: 10.1021/nn405719x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith RJ, King PJ, Lotya M, Wirtz C, Khan U, De S, O'Neill A, Duesberg GS, Grunlan JC, Moriarty G. Large-Scale Exfoliation of Inorganic Layered Compounds in Aqueous Surfactant Solutions. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:3944–3948. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eda G, Yamaguchi H, Voiry D, Fujita T, Chen M, Chhowalla M. Photoluminescence from chemically exfoliated MoS2. Nano Lett. 2011;11:5111–5116. doi: 10.1021/nl201874w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukowski MA, Daniel AS, English CR, Meng F, Forticaux A, Hamers RJ, Jin S. Highly Active Hydrogen Evolution Catalysis from Metallic WS2 Nanosheets. Energy & Environmental Science. 2014;7:2608–2613. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H. Ultrathin Two-Dimensional Nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2015;9:9451–9469. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, Wu J, Yin Z, Zhang H. Preparation and Applications of Mechanically Exfoliated Single-Layer and Multilayer MoS2 and WSe2 Nanosheets. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:1067–1075. doi: 10.1021/ar4002312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang X, Tan C, Yin Z, Zhang H. 25th Anniversary Article: Hybrid Nanostructures Based on Two - Dimensional Nanomaterials. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:2185–2204. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan C, Zhang H. Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Nanosheet-Based Composites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:2713–2731. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00182f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng Z, Yin Z, Huang X, Li H, He Q, Lu G, Boey F, Zhang H. Single - Layer Semiconducting Nanosheets: High - Yield Preparation and Device Fabrication. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:11093–11097. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mak KF, Lee C, Hone J, Shan J, Heinz TF. Atomically Thin MoS2: a New Direct-Gap Semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:136805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.136805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radisavljevic B, Radenovic A, Brivio J, Giacometti V, Kis A. Single-Layer MoS2 Transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6:147–150. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mouri S, Miyauchi Y, Matsuda K. Tunable Photoluminescence of Monolayer MoS2 via Chemical Doping. Nano Lett. 2013;13:5944–5948. doi: 10.1021/nl403036h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin Z, Li H, Li H, Jiang L, Shi Y, Sun Y, Lu G, Zhang Q, Chen X, Zhang H. Single-Layer MoS2 Phototransistors. ACS Nano. 2011;6:74–80. doi: 10.1021/nn2024557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Yin Z, He Q, Li H, Huang X, Lu G, Fam DWH, Tok AIY, Zhang Q, Zhang H. Fabrication of Single - and Multilayer MoS2 Film - Based Field - Effect Transistors for Sensing NO at Room Temperature. Small. 2012;8:63–67. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chhowalla M, Shin HS, Eda G, Li L-J, Loh KP, Zhang H. The Chemistry of Two-Dimensional Layered Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:263–275. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baysinger G. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Zhou Z, Zhang S, Chen Z. MoS2 Nanoribbons: High Stability and Unusual Electronic and Magnetic Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16739–16744. doi: 10.1021/ja805545x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santosh K, Longo RC, Wallace RM, Cho K. Surface Oxidation Energetics and Kinetics on MoS2 Monolayer. J. Appl. Phys. 2015;117:135301. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross S, Sussman A. Surface Oxidation of Molybdenum Disulfide. J. Phys. Chem. 1955;59:889–892. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto M, Einstein TL, Fuhrer MS, Cullen WG. Anisotropic Etching of Atomically Thin MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. 2013;117:25643–25649. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Tan C, Chou H, Nayak A, Wu D, Ghosh R, Chang H-Y, Hao Y, Wang X, Kim J-S. Thermal Oxidation of WSe2 Nanosheets Adhered on SiO2/Si Substrates. Nano Lett. 2015;15:4979–4984. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao J, Li B, Tan J, Chow P, Lu T-M, Koratkar N. Aging of Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Monolayers. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2628–2635. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mancini MC, Kairdolf BA, Smith AM, Nie S. Oxidative Quenching and Degradation of Polymer-Encapsulated Quantum Dots: New Insights into the Long-Term Fate and Toxicity of Nanocrystals in vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10836–10837. doi: 10.1021/ja8040477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pichaandi J, Abel KA, Johnson NJ, van Veggel FC. Long-Term Colloidal Stability and Photoluminescence Retention of Lead-Based Quantum Dots in Saline Buffers and Biological Media through Surface Modification. Chem. Mater. 2013;25:2035–2044. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li BL, Chen LX, Zou HL, Lei JL, Luo HQ, Li NB. Electrochemically Induced Fenton Reaction of Few-Layer MoS2 Nanosheets: Preparation of Luminescent Quantum Dots via a Transition of Nanoporous Morphology. Nanoscale. 2014;6:9831–9838. doi: 10.1039/c4nr02592j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guardia L, Paredes JI, Munuera JM, Villar-Rodil S, Ayán-Varela M, Martínez-Alonso A, Tascón JM. Chemically Exfoliated MoS2 Nanosheets as an Efficient Catalyst for Reduction Reactions in the Aqueous Phase. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:21702–21710. doi: 10.1021/am506922q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J, Hurt RH. Ion Release Kinetics and Particle Persistence in Aqueous Nano-Silver Colloids. Environ. Sci. Techol. 2010;44:2169–2175. doi: 10.1021/es9035557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wypych F, Schollhorn R. 1T-MoS2, a New Metallic Modification of Molybdenum Disulfide. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992:1386–1388. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chou SS, De M, Kim J, Byun S, Dykstra C, Yu J, Huang J, Dravid VP. Ligand Conjugation of Chemically Exfoliated MoS2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4584–4587. doi: 10.1021/ja310929s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Py M, Haering R. Structural Destabilization Induced by Lithium Intercalation in MoS2 and Related Compounds. Can. J. Phys. 1983;61:76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertolazzi S, Brivio J, Kis A. Stretching and Breaking of Ultrathin MoS2. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9703–9709. doi: 10.1021/nn203879f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lembke D, Kis A. Breakdown of High-Performance Monolayer MoS2 Transistors. ACS Nano. 2012;6:10070–10075. doi: 10.1021/nn303772b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chou SS, Kaehr B, Kim J, Foley BM, De M, Hopkins PE, Huang J, Brinker CJ, Dravid VP. Chemically Exfoliated MoS2 as Near-Infrared Photothermal Agents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:4160–4164. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu T, Wang C, Gu X, Gong H, Cheng L, Shi X, Feng L, Sun B, Liu Z. Drug Delivery with PEGylated MoS2 Nano-Sheets for Combined Photothermal and Chemotherapy of Cancer. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:3433–3440. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ju H, Jia L, Ding L, Tian J, Bao L, Hu Y, Yu J-S. Aptamer Loaded MoS2 Nanoplates as Nanoprobe for Detection of Intracellular ATP and Controllable Photodynamic Therapy. Nanoscale. 2015;7:15953–15961. doi: 10.1039/c5nr02224j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chow PK, Singh E, Viana BC, Gao J, Luo J, Li J, Lin Z, Elías AL, Shi Y, Wang Z. Wetting of Mono and Few-Layered WS2 and MoS2 Films Supported on Si/SiO2 Substrates. ACS Nano. 2015;9:3023–3031. doi: 10.1021/nn5072073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chow PK, Jacobs-Gedrim RB, Gao J, Lu T-M, Yu B, Terrones H, Koratkar N. Defect-Induced Photoluminescence in Monolayer Semiconducting Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. ACS Nano. 2015;9:1520–1527. doi: 10.1021/nn5073495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding Q, Meng F, English CR, Cabán-Acevedo M, Shearer MJ, Liang D, Daniel AS, Hamers RJ, Jin S. Efficient Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Generation Using Heterostructures of Si and Chemically Exfoliated Metallic MoS2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:8504–8507. doi: 10.1021/ja5025673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chng ELK, Sofer Z, Pumera M. MoS2 Exhibits Stronger Toxicity with Increased Exfoliation. Nanoscale. 2014;6:14412–14418. doi: 10.1039/c4nr04907a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teo WZ, Chng ELK, Sofer Z, Pumera M. Cytotoxicity of Exfoliated Transition - Metal Dichalcogenides (MoS2, WS2, and WSe2) is Lower Than That of Graphene and its Analogues. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:9627–9632. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fan J, Li Y, Nguyen HN, Yao Y, Rodrigues DF. Toxicity of Exfoliated-MoS2 and Annealed Exfoliated-MoS2 towards Planktonic Cells, Biofilms, and Mammalian Cells in the Presence of Electron Donor. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2015;2:370–379. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah P, Narayanan TN, Li C-Z, Alwarappan S. Probing the Biocompatibility of MoS2 Nanosheets by Cytotoxicity Assay and Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy. Nanotechnology. 2015;26:315102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/26/31/315102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen S, Wang L-W. Thermodynamic Oxidation and Reduction Potentials of Photocatalytic Semiconductors in Aqueous Solution. Chem. Mater. 2012;24:3659–3666. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu W, Yang X, Zhang Y, Xu M, Chen H. Ultra-Stable Two-Dimensional MoS2 Solution for Highly Efficient Organic Solar Cells. RSC Adv. 2014;4:32744–32748. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heising J, Kanatzidis MG. Exfoliated and Restacked MoS2 and WS2: Ionic or Neutral Species? Encapsulation and Ordering of Hard Electropositive Cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11720–11732. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tay CY, Setyawati MI, Xie J, Parak WJ, Leong DT. Back to Basics: Exploiting the Innate Physico - chemical Characteristics of Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014;24:5936–5955. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eda G, Fujita T, Yamaguchi H, Voiry D, Chen M, Chhowalla M. Coherent Atomic and Electronic Heterostructures of Single-Layer MoS2. ACS Nano. 2012;6:7311–7317. doi: 10.1021/nn302422x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bosecker K. Bioleaching: Metal Solubilization by Microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1997;20:591–604. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schippers A, Sand W. Bacterial Leaching of Metal Sulfides Proceeds by Two Indirect Mechanisms via Thiosulfate or via Polysulfides and Sulfur. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:319–321. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.1.319-321.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bryner L, Anderson R. Microorganisms in Leaching Sulfide Minerals. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1957;49:1721–1724. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang XD, Chen J, Min Y, Park GB, Shen X, Song SS, Sun YM, Wang H, Long W, Xie J. Metabolizable Bi2Se3 Nanoplates: Biodistribution, Toxicity, and Uses for Cancer Radiation Therapy and Imaging. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014;24:1718–1729. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee DS, Qian H, Tay CY, Leong DT. Cellular Processing and Destinies of Artificial DNA Nanostructures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1039/c5cs00700c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.