Abstract

Background

The presence of a high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been associated with increased mortality in several malignancies. Here, we quantify the effect of NLR on survival in patients with breast cancer, and examine the effect of clinicopathologic factors on its prognostic value.

Methods

A systematic search of electronic databases was conducted to identify publications exploring the association of blood NLR (measured pre treatment) and overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) among patients with breast cancer. Data from studies reporting a hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) or a P value were pooled in a meta-analysis. Pooled HRs were computed and weighted using generic inverse variance. Meta-regression was performed to evaluate the influence of clinicopathologic factors such as age, disease stage, tumor grade, nodal involvement, receptor status, and NLR cutoff on the HR for OS and DFS. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Fifteen studies comprising a total of 8563 patients were included. The studies used different cutoff values to classify high NLR (range 1.9–5.0). The median cutoff value for high NLR used in these studies was 3.0 amongst 13 studies reporting a HR for OS, and 2.5 in 10 studies reporting DFS outcomes. NLR greater than the cutoff value was associated with worse OS (HR 2.56, 95% CI = 1.96–3.35; P < 0.001) and DFS (HR 1.74, 95% CI = 1.47–2.07; P < 0.001). This association was similar in studies including only early-stage disease and those comprising patients with both early-stage and metastatic disease. Estrogen receptor (ER) and HER-2 appeared to modify the effect of NLR on DFS, because NLR had greater prognostic value for DFS in ER-negative and HER2-negative breast cancer. No subgroup showed an influence on the association between NLR and OS.

Conclusions

High NLR is associated with an adverse OS and DFS in patients with breast cancer with a greater effect on disease-specific outcome in ER and HER2-negative disease. NLR is an easily accessible prognostic marker, and its addition to established risk prediction models warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, Prognosis, Disease-free survival, Overall survival, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Background

The short-term and long-term prognosis of breast cancer depends on patient and tumor factors such as age, disease stage, and biological factors such as grade and receptor status. However, the behavior of breast cancer is unpredictable, with markedly different clinical outcomes seen even amongst patients with similar classical prognostic factors [1].

Inflammatory cells and mediators in the tumor microenvironment are thought to play an important role in cancer progression, and may account for some of this variability [2]. The presence of an elevated peripheral neutrophil-to-lymphocyte (NLR) ratio, an indicator of systemic inflammation, has been recognized as a poor prognostic factor in various cancers [3]. In a previous meta-analysis of 100 studies of patients with unselected solid tumors, increased NLR was associated with decreased overall survival (OS) (hazard ratio (HR) 1.81; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.67–1.97; P < 0.001) [4]. This effect was observed in all disease sites, subgroups, and stages. However, this study was not specific to breast cancer, and did not examine the impact of prognostic factors such as estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR) status, HER2 status, disease stage, or menopausal status.

The aim of this study was to quantify the effect of peripheral blood NLR on OS and disease-free survival (DFS) in adult women with invasive breast cancer. We also examined the effect of clinicopathologic factors on the prognostic value of NLR.

Methods

Data sources and searches

This analysis was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [5]. The search strategy developed by Templeton et al. [4] was used with the addition of “breast neoplasms” and synonymous breast cancer-specific terms. An electronic search of the following databases was performed: Medline (host: OVID), Medline in Process, Medline Epub Ahead of Print (host: OVID), EMBASE (host: OVID), and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. All databases were searched from January 2013 to April 2016, supplementing the initial systematic review that searched databases until different time points in 2013. Citation lists of retrieved articles were screened manually to ensure sensitivity of the search strategy. The full search strategy is described in Table 3 in Appendix 1.

Study selection

In order to reduce clinical heterogeneity, the following eligibility criteria were utilized: studies of adult women with breast cancer reporting on the prognostic impact of the peripheral blood NLR, where NLR was treated as a categorical variable; NLR collected prior to all treatment (surgery and/or systemic therapy); reporting of a multivariable HR for OS, and/or DFS or progression-free survival (PFS), and corresponding 95% CI and/or P value; available as a full-text publication; clinical trials, cohort studies, or case–control studies; and English-language publication. Case reports, conference proceedings, and letters to editors were excluded. Corresponding authors were contacted to clarify missing or ambiguous data. When multiple publications or data analyses were available from the same dataset and if clarification on potentially duplicate data could not be obtained, the study reporting the larger number of patients was retained and other studies were excluded. Studies only presenting data in graphic form without reporting a numerical value for HR were excluded. All titles identified by the search were evaluated, and all potentially relevant publications were retrieved in full. Two reviewers (JE and DD) independently reviewed full articles for eligibility based on inclusion criteria and data extraction, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. Three relevant articles identified in the previous systematic review were also included [4].

Data extraction

The following details were extracted from included studies using predesigned data abstraction forms: name of first author, year of publication, journal, number of patients included in analysis, median age, disease stage (nonmetastatic, metastatic, mixed (nonmetastatic and metastatic)), collection of data (prospective, retrospective), cutoff value used to define high NLR, number of patients with each breast cancer subtype, number of premenopausal and postmenopausal patients, and HRs and associated 95% CIs for OS, PFS, or DFS. Where more than one multivariable model was reported, HRs were extracted from models including the most participants.

Risk of bias assessment

Validity of included studies was assessed by two independent reviewers (J-LE and DD) using the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool as described previously [6]. The QUIPS tool comprises 30 questions categorized into six domains (study participation, study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, study confounding, and statistical analysis and reporting). Studies were rated according to each domain as being at low, moderate, or high risk of bias, based on the likelihood that they might alter the relationship between the prognostic factor and outcome.

Statistical analyses

Extracted data were pooled using RevMan 5.3 analysis software (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). A meta-analysis was conducted for all included studies for each of the endpoints of interest if appropriate when clinical heterogeneity was minimal. The primary outcome of interest was OS, and intermediate endpoints such as PFS and/or DFS were secondary outcomes. Estimates for HRs were pooled and weighted by generic inverse variance, and were computed by fixed-effects or random-effects modeling. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran Q and I 2 statistics. If significant heterogeneity was present (I 2 > 50% or Cochran Q < 0.1), a random-effects model was used. Predefined subgroup analyses were conducted for disease stage (early, metastatic, mixed) using methods described by Deeks et al. [7] Meta-regression was performed to evaluate the effects of NLR cutoff, proportion of ER-positive patients, proportion of HER2-positive patients, proportion of triple-negative patients, median age, proportion of premenopausal patients, and proportion of patients with metastatic disease on the HR for OS and DFS. Meta-regression comprised a univariable linear regression weighted by individual study inverse variance and was performed using SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). A post-hoc meta-regression analysis testing the association between median duration of follow-up and the prognostic value of NLR was also performed. Multivariable meta-regression was not performed due to the small number of eligible studies leading to an undesirable risk of over-fitting. Publication bias was assessed by inspecting funnel plots visually. All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

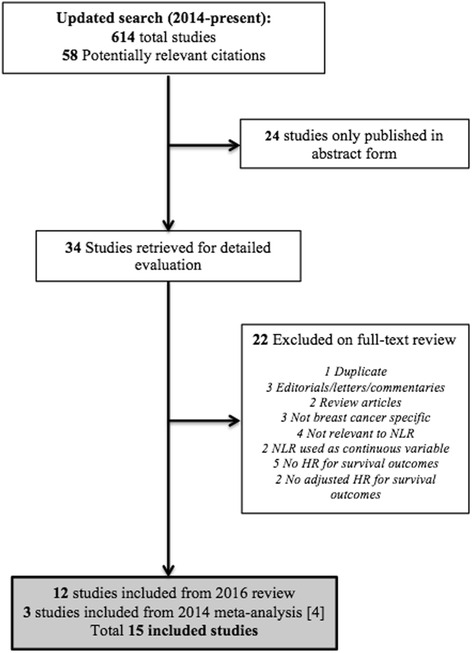

Fifteen studies comprising a total of 8563 patients were included (Fig. 1). Characteristics of included studies are described in Table 1, and further details are included in Table 4 in Appendix 2. All studies collected data retrospectively, and all were published in 2012 or later. Ten studies included only patients with early-stage breast cancer, while five included both early and metastatic disease.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection process. HR hazard ratio, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Year | Number of patients | Disease stage | NLR cutoff value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||

| Azab et al. [23]a | 2012 | 316 | Mixed | 3.3 |

| Azab et al. [13]a | 2013 | 437 | Mixed | 3.3 |

| Bozkurt et al. [24] | 2015 | 85 | Early | 2.0 |

| Dirican et al. [25] | 2015 | 1527 | Mixed | 4.0 |

| Forget et al. [10] | 2014 | 720 | Early | 3.3 |

| Jia et al. [14] | 2015 | 1570 | Early | 2.0 |

| Koh et al. [8] | 2014 | 157 | Early | 2.3 |

| Koh et al. [15] | 2015 | 1435 | Mixed | 5.0 |

| Nakano et al. [9] | 2015 | 167 | Early | 2.5 |

| Noh et al. [26]a | 2013 | 442 | Early | 2.5 |

| Pistelli et al. [27] | 2015 | 90 | Early | 3.0 |

| Rimando et al. [28] | 2016 | 461 | Mixed | 3.8 |

| Yao et al. [11] | 2014 | 608 | Early | 2.6 |

| Disease-free survival | ||||

| Asano et al. [12] | 2016 | 61 | Early | 3.0 |

| Bozkurt et al. [24] | 2015 | 85 | Early | 2.0 |

| Dirican et al. [25] | 2015 | 1527 | Mixed | 4.0 |

| Forget et al. [10] | 2014 | 720 | Early | 3.3 |

| Hong et al. [29] | 2015 | 487 | Early | 1.9 |

| Jia et al. [14] | 2015 | 1570 | Early | 2.0 |

| Koh et al. [8] | 2014 | 157 | Early | 2.3 |

| Nakano et al. [9] | 2015 | 167 | Early | 2.5 |

| Pistelli et al. [27] | 2015 | 90 | Early | 3.0 |

NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

aIncluded in previous meta-analysis [4]

Overall survival

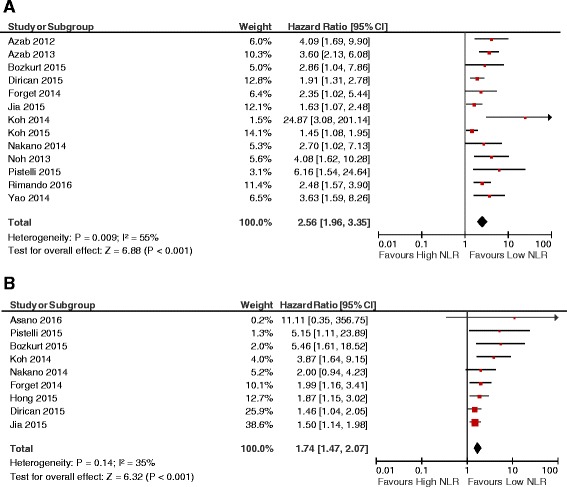

Thirteen studies comprising a total of 8015 patients reported adjusted HRs for OS. The median cutoff value for high NLR was 3.0 (range 2.0–5.0). Median follow-up was reported in 11 studies, and ranged from 1.8 to 7.2 years (mean 4.69 years) (Table 4 in Appendix 2). Overall, a NLR greater than the cutoff value was associated with worse OS (HR 2.56, 95% CI = 1.96–3.35; P < 0.001; see Fig. 2). There was statistically significant heterogeneity (Cochran Q = 0.009, I 2 = 55%). This seems to be largely influenced by one study which showed a large effect size [8]. However, the association between NLR and OS was maintained in a sensitivity analysis omitting this study (HR 2.42, 95% CI = 1.89–3.09; P < 0.001; Cochran Q = 0.03, I 2 = 48%), although statistically significant heterogeneity remained.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots showing HRs for OS (a) and DFS (b) for neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) greater than or less than the cutoff value. HRs for each study represented by squares: size of the square represents the weight of the study in the meta-analysis, and the horizontal line crossing the square represents the 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical tests were two-sided

Exploratory analysis identified breast cancer stage as an important source of heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis showed that the association between NLR and OS was maintained in studies including only early-stage disease, as well as those comprised of patients with both early and metastatic disease (HR 2.98 vs 2.30 respectively; P for subgroup differences = 0.36). There was no statistical heterogeneity when the study driving heterogeneity in the main analysis [8] was omitted from the early stage subgroup (Cochran Q = 0.28, I 2 = 20%). Additionally, the effect of NLR on OS was retained (HR 2.56, 95% CI = 1.82–3.60; P < 0.001). Statistical heterogeneity remained among studies with mixed early and metastatic disease (Cochran Q = 0.01, I 2 = 69%).

Adjustment for age differences between arms was examined in individual studies. In one study, patients were significantly older in the arm with low NLR, and it was unclear whether the multivariable model was adjusted for age [9]. In two other studies, the median age in each arm was not reported, and age did not seem to be included in the multivariable model [10, 11]. In a sensitivity analysis excluding these three studies, high NLR remained a significant predictor for shorter OS (HR 2.55, 95% CI = 2.59–8.26; P < 0.001). Table 2 presents the results of the meta-regression analysis. We did not identify any classical clinicopathologic factors that were effect modifiers for influence of NLR on OS. Additionally, the median duration of follow-up did not affect the association between high NLR and OS.

Table 2.

Meta-regression for the association of clinicopathologic factors and the hazard ratio for disease-free and overall survival

| Variable | Studies included in analysis | Standardized β coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | |||

| Median age | [8, 9, 11, 13–15, 26–28] | 0.098 | 0.80 |

| ER positive | [9–11, 13, 15, 23–27] | 0.084 | 0.81 |

| HER2 positive | [8–11, 14, 15, 23–27] | –0.40 | 0.22 |

| Triple negative | [8, 14, 24, 27] | 0.05 | 0.93 |

| Grade 1 or 2 | [8, 10, 14, 15, 23–25] | 0.02 | 0.95 |

| Grade 3 | [8, 10, 14, 15, 23–25] | –0.02 | 0.95 |

| Stage 0–I | [9, 13, 23, 25, 27, 28] | 0.68 | 0.14 |

| Stage II | [9, 13, 23, 25, 27, 28] | –0.30 | 0.56 |

| Stage III | [9, 13, 25, 27, 28] | –0.73 | 0.16 |

| Metastatic disease | [8–11, 13–15, 24–28] | –0.29 | 0.35 |

| Premenopausal | [24, 25] | 0.04 | 0.95 |

| Nodal involvement | [8–11, 13–15, 23–27] | –0.04 | 0.90 |

| NLR cutoff value | [8, 10, 13–15, 23, 24] | –0.29 | 0.33 |

| Median follow-up | [8–11, 13, 14, 23, 25–28] | –0.16 | 0.64 |

| Disease-free survival | |||

| Median age | [8, 9, 14, 27, 29] | 0.06 | 0.93 |

| ER positive | [9, 10, 12, 24, 25, 27, 29] | –0.77 | 0.04* |

| HER2 positive | [8–10, 12, 14, 24, 25, 27, 29] | –0.79 | 0.01* |

| Triple negative | [8, 12, 14, 24, 27, 29] | 0.63 | 0.18 |

| Grade 1 or 2 | [8–10, 12, 14, 24, 25, 27, 29] | –0.46 | 0.21 |

| Grade 3 | [8–10, 12, 14, 24, 25, 27, 29] | 0.46 | 0.21 |

| Stage 0–I | [9, 25, 27, 29] | 0.46 | 0.54 |

| Stage II | [9, 25, 27, 29] | 0.53 | 0.36 |

| Stage III | [9, 25, 27, 29] | –0.50 | 0.39 |

| Metastatic disease | [25] | –0.74 | 0.49 |

| Premenopausal | [9, 12, 24, 25, 27] | 0.43 | 0.40 |

| Nodal involvement | [8–10, 12, 14, 24, 25, 27, 29] | 0.25 | 0.52 |

| NLR cutoff value | [8–10, 12, 14, 24, 25, 27, 29] | –0.15 | 0.70 |

| Median follow-up | [8–10, 12, 14, 25, 27, 29] | –0.19 | 0.66 |

ER estrogen receptor, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

*Statistically significant at P < 0.05

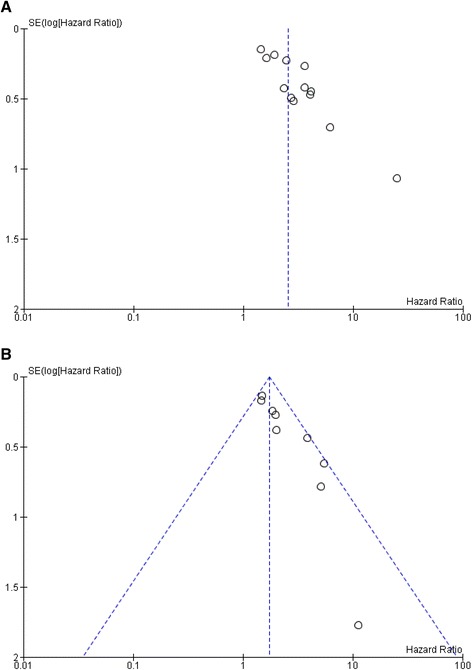

There was evidence of publication bias, with fewer smaller studies reporting lower magnitude associations between NLR and OS (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Funnel plots of HR for OS (a) and DFS (b) for high NLR ratio (horizontal axis) and the standard error (SE) for the HR (vertical axis). Each study is represented by one circle. Vertical line represents the pooled effect estimate

Disease-free survival

Nine studies comprising 4864 patients reported HRs for DFS. All studies included only patients with nonmetastatic disease. The median cutoff value for high NLR was 2.5 (range 1.9–4.0). Median length of follow-up was reported in eight studies, ranging from 1.8 to 7.2 years (mean 4.5 years) (Table 4 in Appendix 2). Overall, a NLR greater than the cutoff value was associated with worse DFS (HR 1.74, 95% CI = 1.47–2.07; P < 0.001; see Fig. 2). There was no evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity (Cochran Q = 0.14, I 2 = 35%).

Adjustment for age differences between arms was examined in individual studies. Two studies had significant age differences between arms and no clear model adjustment for age, including one study where patients were significantly older in the arm with low NLR [9] and one study where the same group was significantly younger [12]. Another study did not report the median age in each arm and did not adjust for age in the multivariable model [10]. In a sensitivity analysis excluding these three studies, high NLR remained a significant predictor for shorter DFS (HR 1.69, 95% CI = 1.40–2.03; P < 0.001).

All studies reported the number of patients with HER2-positive disease, while seven of nine studies included data on ER status (Table 4 in Appendix 2). Meta-regression analysis is presented in Table 2. Results showed that ER and HER2 positivity were negative effect modifiers of the association between NLR and DFS, indicating that the NLR has a greater prognostic value in breast cancers that are ER-negative and/or HER2-negative. The proportion of patients with triple-negative or metastatic disease, median age, disease stage, histologic tumor grade, presence of nodal involvement, premenopausal status, median duration of follow-up, and NLR cutoff value did not affect the association between high NLR and DFS. There was evidence of publication bias, with fewer smaller studies reporting lower magnitude associations between NLR and DFS (Fig. 3).

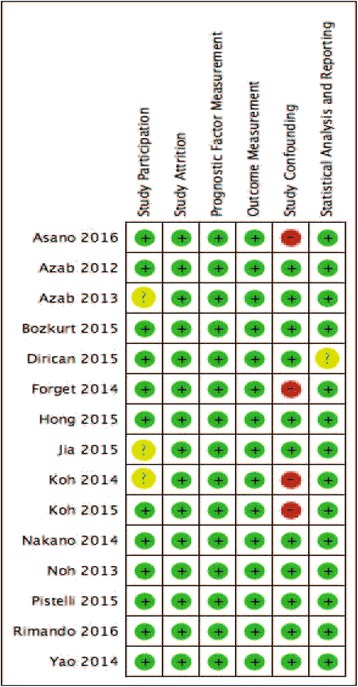

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in individual studies is summarized in Figure 4 in Appendix 3. Overall, risk of bias was low, particularly in the domains of study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, and statistical analysis and reporting. There was a low–moderate risk of bias for the study participation domain due to lack of completeness in description of the baseline study sample in three studies [8, 13, 14]. Risk of bias was moderate with regards to study confounding, because four studies failed to adequately detail covariates included in adjusted models [8, 10, 12, 15].

Discussion

High NLR is associated with poor survival in patients diagnosed with several types of cancer [4]. Here we performed a breast cancer-specific meta-analysis, including 15 studies comprising 8563 patients, and found a significant prognostic effect for NLR on both OS and DFS. While there was evidence of publication bias, potentially indicating bias towards publication of positive studies, the overall risk of bias was low, as assessed with the QUIPS tool.

The magnitude of effect on DFS was highest in ER-negative and HER2-negative subtypes. However, this finding does not rule out an effect in ER-positive or HER2-positive subgroups. Rather, the finding indicates a greater magnitude of effect in ER-negative and/or HER2-negative breast cancers. It is possible that the smaller magnitude of effect seen in ER-positive and/or HER2-positive disease relates to the relatively short duration of follow-up of included studies; recurrences occur later in follow-up with ER-positive disease compared with ER-negative disease. However, in a post-hoc meta-regression analysis, median follow-up did not significantly alter the association of NLR with either DFS or OS. Unfortunately, a stratified meta-regression based on ER status was not possible. Some uncertainty therefore remains about the effect of duration of follow-up on subgroups defined by receptor expression.

Despite a greater magnitude of association between NLR and DFS in certain subgroups, patient and disease characteristics did not significantly alter the magnitude of effect of NLR on OS. The negative prognostic effect of NLR on OS was consistent in all clinicopathologic groups and was not influenced by the duration of follow-up in individual studies. One possible explanation for this is that a proportion of breast cancer patients die of causes other than breast cancer, especially cardiovascular disease [16, 17]. Increased NLR has been associated with higher coronary heart disease mortality [18]. The competing risks of cardiovascular and breast cancer deaths may have led to difficulty in exploring the influence of breast cancer-specific characteristics on OS.

While the association between increased NLR and poor outcomes is not fully understood, it has been proposed that high NLR may be indicative of inflammation. In particular, neutrophils have been shown to inhibit the immune system and promote tumor growth by suppressing the activity of lymphocytes and T-cell response [19, 20]. Increased lymphocytic tumor infiltration has also been associated with improved DFS in ER-negative/HER2-negative breast cancer [21]. In our study, we found a greater magnitude of effect on DFS in patients with ER-negative and/or HER2-negative disease. However, while this indicates the potential importance of lymphocyte activity, the association between increased tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and peripheral blood lymphocytes remains unclear. Furthermore, the greater magnitude of association in patients with ER-negative and/or HER2-negative breast cancers was not seen with triple-negative disease. This observation may be due to the relatively small number of studies reporting outcomes in patients with triple-negative breast cancer; the majority of studies identified patients based on independent subgroups based on ER and HER2 status.

While there are several clinicopathologic factors associated with increased risk of recurrence and/or mortality in patients with breast cancer, the NLR is an inexpensive, readily available prognostic marker, and may allow refinement of risk estimates within disease stages and subgroups. Future studies using NLR in combination with other prognostic markers could potentially identify lower risk patients in whom treatment de-escalation may be appropriate. Furthermore, whether NLR is predictive of response to treatment or provides additional information in cases where risk stratification models exist, such as the 21-gene assay in node-negative ER-positive/HER2-negative disease, is unknown. However, previous research showed no association between NLR and the 21-gene assay recurrence score, indicating that the poor outcomes in patients with high NLR cannot be explained by the proliferation of ER signaling [22]. Further studies examining whether NLR may help refine established prognostic scores are therefore warranted.

Conclusion

High NLR is associated with an adverse OS and DFS in patients with breast cancer, and its prognostic value is consistent among different clinicopathologic factors such as disease stage and subtype. NLR is an easily accessible prognostic marker, and its addition to established risk prediction models warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Rouhi Fazelzad for conducting the literature search.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Detailed characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 4 in Appendix 2.

Authors’ contributions

J-LE collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. DD was the second reviewer for data collection, analysis, and risk of bias assessment. EA, AT, and PSS also participated in data analysis and interpretation, as well as manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. Literature reviews and meta-analyses do not require patient consent for publication in Canada.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Literature reviews and meta-analyses do not require ethics approval in Canada.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- HR

Hazard ratio

- NLR

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- SE

Standard error

Appendix 1

Table 3.

Search strategya

| Number | Searches | Results | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Breast Neoplasms/ | 241,242 | Advanced |

| 2 | (breast? adj6 cancer*).mp,kw. | 203,097 | Advanced |

| 3 | (breast? adj6 neoplas*).mp,kw. | 241,382 | Advanced |

| 4 | (breast? adj6 carcin*).mp,kw. | 62,218 | Advanced |

| 5 | (breast? adj6 tumo?r*).mp,kw. | 46,556 | Advanced |

| 6 | (breast? adj6 adenocarcin*).mp,kw. | 4642 | Advanced |

| 7 | (breast? adj6 adeno-carcin*).mp,kw. | 10 | Advanced |

| 8 | (breast? adj6 sarcoma*).mp,kw. | 1271 | Advanced |

| 9 | (breast? adj6 dcis).mp,kw. | 1258 | Advanced |

| 10 | (breast? adj6 ductal).mp,kw. | 16,064 | Advanced |

| 11 | (breast? adj6 infiltrating).mp,kw. | 1418 | Advanced |

| 12 | (breast? adj6 intraductal).mp,kw. | 2294 | Advanced |

| 13 | (breast? adj6 lobular).mp,kw. | 4044 | Advanced |

| 14 | (breast? adj6 medullary).mp,kw. | 383 | Advanced |

| 15 | (breast? adj6 comedo*).mp,kw. | 75 | Advanced |

| 16 | (breast? adj6 metast*).mp,kw. | 26,054 | Advanced |

| 17 | (breast? adj2 malignan*).mp,kw. | 4962 | Advanced |

| 18 | (breast? adj6 onco*).mp,kw. | 3338 | Advanced |

| 19 | (mammar* adj6 cancer*).mp,kw. | 5493 | Advanced |

| 20 | (mammar* adj6 neoplas*).mp,kw. | 21,985 | Advanced |

| 21 | (mammar* adj6 carcin*).mp,kw. | 11,584 | Advanced |

| 22 | (mammar* adj6 tumo?r*).mp,kw. | 18,026 | Advanced |

| 23 | (mammar* adj6 adenocarcin*).mp,kw. | 2958 | Advanced |

| 24 | (mammar* adj6 adeno-carcin*).mp,kw. | 3 | Advanced |

| 25 | (mammar* adj6 sarcoma*).mp,kw. | 384 | Advanced |

| 26 | (mammar* adj6 ductal).mp,kw. | 937 | Advanced |

| 27 | (mammar* adj6 intraductal).mp,kw. | 117 | Advanced |

| 28 | (mammar* adj6 infiltrating).mp,kw. | 201 | Advanced |

| 29 | (mammar* adj6 lobular).mp,kw. | 151 | Advanced |

| 30 | (mammar* adj6 medullary).mp,kw. | 19 | Advanced |

| 31 | (mammar* adj6 comedo*).mp,kw. | 6 | Advanced |

| 32 | (mammar* adj6 metast*).mp,kw. | 2554 | Advanced |

| 33 | (mammar* adj6 malignan*).mp,kw. | 1506 | Advanced |

| 34 | (mammar* adj6 dcis).mp,kw. | 61 | Advanced |

| 35 | (ductal adj6 situ).mp,kw. | 6301 | Advanced |

| 36 | (ductal adj6 carcino*).mp,kw. | 25,790 | Advanced |

| 37 | (paget?? adj6 breast?).mp,kw. | 367 | Advanced |

| 38 | (paget?? adj6 nipple?).mp,kw. | 363 | Advanced |

| 39 | phyllodes.mp,kw. | 1876 | Advanced |

| 40 | phylloides.mp,kw. | 206 | Advanced |

| 41 | cystosarcoma*.mp,kw. | 603 | Advanced |

| 42 | DCIS.mp,kw. | 3401 | Advanced |

| 43 | or/1-40 | 318,397 | Advanced |

| 44 | exp Ovarian Neoplasms/ | 71,707 | Advanced |

| 45 | (ovar* adj6 cancer*).mp,kw. | 44,037 | Advanced |

| 46 | (ovar* adj6 neoplas*).mp,kw. | 71,929 | Advanced |

| 47 | (ovar* adj6 tumo?r*).mp,kw. | 24,113 | Advanced |

| 48 | (ovar* adj6 malignan*).mp,kw. | 7601 | Advanced |

| 49 | (ovar* adj6 metasta*).mp,kw. | 5781 | Advanced |

| 50 | (ovar* adj6 carcin*).mp,kw. | 18,742 | Advanced |

| 51 | (ovar* adj6 adenocarcin*).mp,kw. | 2966 | Advanced |

| 52 | (ovar* adj6 adeno-carcin*).mp,kw. | 12 | Advanced |

| 53 | (ovar* adj6 choriocarcin*).mp,kw. | 217 | Advanced |

| 54 | (granulosa adj6 cancer*).mp,kw. | 54 | Advanced |

| 55 | (granulosa adj6 tumo?r*).mp,kw. | 2699 | Advanced |

| 56 | (granulosa adj6 neoplas*).mp,kw. | 173 | Advanced |

| 57 | (granulosa adj6 malignan*).mp,kw. | 142 | Advanced |

| 58 | (granulosa adj6 metasta*).mp,kw. | 111 | Advanced |

| 59 | (granulosa adj6 carcin*).mp,kw. | 118 | Advanced |

| 60 | (granulosa adj6 adenocarcin*).mp,kw. | 45 | Advanced |

| 61 | (granulosa adj6 adeno-carcin*).mp,kw. | 0 | Advanced |

| 62 | OGCTs.mp,kw. | 28 | Advanced |

| 63 | HBOC.mp,kw. | 650 | Advanced |

| 64 | Luteoma*.mp,kw. | 203 | Advanced |

| 65 | Sertoli-Leydig*.mp,kw. | 1039 | Advanced |

| 66 | Thecoma*.mp,kw. | 1013 | Advanced |

| 67 | (theca* adj6 tumo?r*).mp,kw. | 493 | Advanced |

| 68 | (ovar* adj6 dysgerminoma?).mp,kw. | 467 | Advanced |

| 69 | androblastoma*.mp,kw. | 321 | Advanced |

| 70 | arrhenoblastoma*.mp,kw. | 349 | Advanced |

| 71 | arrheno-blastoma*.mp,kw. | 1 | Advanced |

| 72 | Meig*.mp,kw. | 2152 | Advanced |

| 73 | or/44-72 | 93,590 | Advanced |

| 74 | exp Endometrial Neoplasms/ | 17,416 | Advanced |

| 75 | (endometr* adj6 neoplas*).mp,kw. | 17,866 | Advanced |

| 76 | (endometr* adj6 cancer*).mp,kw. | 15,307 | Advanced |

| 77 | (endometr* adj6 tumo?r*).mp,kw. | 5128 | Advanced |

| 78 | (endometr* adj6 carcino*).mp,kw. | 12,730 | Advanced |

| 79 | (endometr* adj6 adenocarcin*).mp,kw. | 5361 | Advanced |

| 80 | (endometr* adj6 adeno-carcin*).mp,kw. | 9 | Advanced |

| 81 | (endometr* adj6 sarcoma*).mp,kw. | 1230 | Advanced |

| 82 | (endometr* adj6 malignan*).mp,kw. | 2300 | Advanced |

| 83 | (endometr* adj6 metast*).mp,kw. | 1337 | Advanced |

| 84 | (endometr* adj6 onco*).mp,kw. | 370 | Advanced |

| 85 | (endometr* adj6 choriocarcin*).mp,kw. | 88 | Advanced |

| 86 | or/74-85 | 31,774 | Advanced |

| 87 | Uterine Cervical Neoplasms/ | 65,130 | Advanced |

| 88 | (cervi* adj6 cancer*).mp,kw. | 41,277 | Advanced |

| 89 | (cervi* adj6 neoplas*).mp,kw. | 69,153 | Advanced |

| 90 | (cervi* adj6 tumo?r*).mp,kw. | 7715 | Advanced |

| 91 | (cervi* adj6 malignan*).mp,kw. | 3006 | Advanced |

| 92 | (cervi* adj6 metast*).mp,kw. | 6612 | Advanced |

| 93 | (cervi* adj6 onco*).mp,kw. | 1280 | Advanced |

| 94 | (cervi* adj6 carcin*).mp,kw. | 24,588 | Advanced |

| 95 | (cervi* adj6 adenocarcin*).mp,kw. | 2945 | Advanced |

| 96 | (cervi* adj6 adeno-carcin*).mp,kw. | 9 | Advanced |

| 97 | (cervi* adj6 squamous*).mp,kw. | 7833 | Advanced |

| 98 | (cervi* adj6 adenosquamous*).mp,kw. | 211 | Advanced |

| 99 | (cervi* adj6 adeno-squamous*).mp,kw. | 2 | Advanced |

| 100 | (cervi* adj6 sarcoma*).mp,kw. | 661 | Advanced |

| 101 | (cervi* adj6 small cell*).mp,kw. | 364 | Advanced |

| 102 | (cervi* adj6 large cell*).mp,kw. | 78 | Advanced |

| 103 | (cervi* adj6 neuroendocrine*).mp,kw. | 195 | Advanced |

| 104 | (cervi* adj6 neuro-endocrine*).mp,kw. | 2 | Advanced |

| 105 | (cervi* adj6 choriocarcin*).mp,kw. | 112 | Advanced |

| 106 | SCCC.mp,kw. | 46 | Advanced |

| 107 | or/87-106 | 90,890 | Advanced |

| 108 | 73 or 86 or 107 | 199,155 | Advanced |

| 109 | exp Lymphocytes/ | 461,529 | Advanced |

| 110 | lymphocyte?.mp,kw. | 554,948 | Advanced |

| 111 | (lymphoid adj2 cell?).mp,kw. | 22,666 | Advanced |

| 112 | (killer adj4 cell?).mp,kw. | 51,337 | Advanced |

| 113 | (nk adj2 cell?).mp,kw. | 31,413 | Advanced |

| 114 | (lak adj2 cell?).mp,kw. | 2650 | Advanced |

| 115 | b-lymphocyte?.mp,kw. | 93,264 | Advanced |

| 116 | t-lymphocyte?.mp,kw. | 290,882 | Advanced |

| 117 | b-lymphoid.mp,kw. | 2219 | Advanced |

| 118 | t-lymphoid.mp,kw. | 1196 | Advanced |

| 119 | (plasm adj2 cell?).mp,kw. | 31 | Advanced |

| 120 | plasmacyte?.mp,kw. | 341 | Advanced |

| 121 | (immune adj3 cell?).mp,kw. | 58,743 | Advanced |

| 122 | (immunocompetent adj2 cell?).mp,kw. | 3494 | Advanced |

| 123 | immnunocyte?.mp,kw. | 0 | Advanced |

| 124 | immnuno-cyte?.mp,kw. | 0 | Advanced |

| 125 | lymph cell?.mp,kw. | 184 | Advanced |

| 126 | null cell?.mp,kw. | 3404 | Advanced |

| 127 | immunological* competent cell?.mp,kw. | 153 | Advanced |

| 128 | immunoreactive cell?.mp,kw. | 6231 | Advanced |

| 129 | immuno-reactive cell?.mp,kw. | 18 | Advanced |

| 130 | prolymphocyte?.mp. | 218 | Advanced |

| 131 | pro-lymphocyte?.mp. | 3 | Advanced |

| 132 | or/109-131 | 648,538 | Advanced |

| 133 | Neutrophils/ | 77,202 | Advanced |

| 134 | neutrophil*.mp,kw. | 135,327 | Advanced |

| 135 | (cell? adj2 le).mp,kw. | 868 | Advanced |

| 136 | (leukocyte? adj3 polymorphonuclear).mp,kw. | 14,471 | Advanced |

| 137 | pmn granulocyte?.mp,kw. | 52 | Advanced |

| 138 | pmn leukocyte?.mp,kw. | 400 | Advanced |

| 139 | (poly morphou* adj2 granulocyte?).mp,kw. | 0 | Advanced |

| 140 | (polynuclear adj3 leukocyte?).mp,kw. | 71 | Advanced |

| 141 | or/133-140 | 139,999 | Advanced |

| 142 | (neutrophil? adj6 lymphocyte?).mp,kw. | 8790 | Advanced |

| 143 | NLR.mp,kw. | 1729 | Advanced |

| 144 | 132 and 141 | 26,722 | Advanced |

| 145 | or/142-144 | 27,810 | Advanced |

| 146 | exp Cohort Studies/ | 1,522,637 | Advanced |

| 147 | exp Prognosis/ | 1,240,142 | Advanced |

| 148 | exp Morbidity/ | 425,952 | Advanced |

| 149 | exp Mortality/ | 309,548 | Advanced |

| 150 | exp survival analysis/ | 214,369 | Advanced |

| 151 | exp models, statistical/ | 311,009 | Advanced |

| 152 | prognos*.mp,kw. | 603,945 | Advanced |

| 153 | predict*.mp,kw. | 1,026,266 | Advanced |

| 154 | course*.mp,kw. | 467,535 | Advanced |

| 155 | diagnosed.mp,kw. | 361,373 | Advanced |

| 156 | cohort*.mp,kw. | 388,862 | Advanced |

| 157 | death?.mp,kw. | 646,834 | Advanced |

| 158 | or/146-157 | 4,572,550 | Advanced |

| 159 | 108 and 145 and 158 | 64 | Advanced |

| 160 | 43 and 145 and 158 | 122 | Advanced |

| 161 | 159 or 160 | 184 | Advanced |

| 162 | limit 161 to yr = “2013-Current” | 85 | Advanced |

aOvid MEDLINE®, 1946–April week 2 2016

Appendix 2

Table 4.

Detailed characteristics of included studies

| Author | Year | Number of patients | Disease stage | NLR cutoff value | Median age (years) | Breast cancer subtype (%) | Grade (%) | Postmenopausal (%) | Median follow-up (years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER+ | HER-2+ | Triple negative | Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | ||||||||

| Asano et al. [12] | 2016 | 61 | Early | 3.0 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 100 | 72 | 28 | 36 | 3.1 |

| Azab et al. [23] | 2012 | 316 | Mixed | 3.3 | n/a | 83 | 17 | n/a | 70 | 30 | n/a | 3.8 |

| Azab et al. [13] | 2013 | 437 | Mixed | 3.3 | 64 | 76 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 5 |

| Bozkurt et al. [24] | 2015 | 85 | Early | 2.0 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 100 | 31 | 69 | 69 | n/a |

| Dirican et al. [25] | 2015 | 1527 | Mixed | 4.0 | n/a | 68 | 17 | n/a | 80 | 20 | 44 | 2.5 |

| Forget et al. [10] | 2014 | 720 | Early | 3.3 | n/a | 84 | 9 | n/a | 61 | 39 | n/a | 5.8 |

| Hong et al. [29] | 2015 | 487 | Early | 1.9 | 55 | 67 | 21 | 19 | 73 | 27 | 42 | 4.6 |

| Jia et al. [14] | 2015 | 1570 | Early | 2.0 | 47 | n/a | 22 | 14 | 62 | 38 | n/a | 6.6 |

| Koh et al. [8] | 2014 | 157 | Early | 2.3 | 44 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 80 | 20 | n/a | 1.8 |

| Koh et al. [15] | 2015 | 1435 | Mixed | 5.0 | 52 | 55 | 36 | 100 | 56 | 44 | n/a | n/a |

| Nakano et al. [9] | 2015 | 167 | Early | 2.5 | 58 | 78 | 18 | n/a | 80 | 20 | 25 | 7.2a |

| Noh et al. [26] | 2013 | 442 | Early | 2.5 | 50 | 71 | 29 | 18 | 71 | 29 | n/a | 5.9 |

| Pistelli et al. [27] | 2015 | 90 | Early | 3.0 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 40 | 4.5 |

| Rimando et al. [28] | 2016 | 461 | Mixed | 3.8 | 58 | 74 | n/a | n/a | 51 | 49 | n/a | 5.1 |

| Yao et al. [11] | 2014 | 608 | Early | 2.6 | 53 | 66 | 25 | 16 | n/a | n/a | 48 | 3.5 |

ER estrogen receptor, n/a not available, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

aMean follow-up

Appendix 3

Fig. 4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgments using the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool [6]. Domains are rated as being at low (+), moderate (?), or high (–) risk of bias

Contributor Information

Josee-Lyne Ethier, Email: josee-lyne.ethier@uhn.ca.

Danielle Desautels, Email: danielle.desautels@sunnybrook.ca.

Arnoud Templeton, Email: arnoud.templeton@unibas.ch.

Prakesh S. Shah, Email: pshah@mtsinai.on.ca

Eitan Amir, Phone: +1 416 946 4501, Email: eitan.amir@uhn.ca.

References

- 1.Masood S. Prognostic/predictive factors in breast cancer. Clin Lab Med. 2005;25:809–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg R. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthrie GJK, Charles KA, Roxburgh CSD, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88(1):218–30. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocana A, Leibowitz-Amit R, Sonpavde G, Knox JJ, Tran B, Tannock IF, Amir E. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hayden J, van der Windt D, Cartwright J, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeks J, Higgins J, Altman D. Chapter 9: Analysing data and under-taking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

- 8.Koh YW, Lee HJ, Ahn JH, Lee JW, Gong G. Prognostic significance of the ratio of absolute neutrophil to lymphocyte counts for breast cancer patients with ER/PR-positivity and HER2-negativity in neoadjuvant setting. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(10):9823–30. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakano K, Hosoda M, Yamamoto M, Yamashita H. Prognostic significance of pre-treatment neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio in Japanese patients with breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(7):3819–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forget P, Bentin C, Machiels JP, Berliere M, Coulie PG, De Kock M. Intraoperative use of ketorolac or diclofenac is associated with improved disease-free survival and overall survival in conservative breast cancer surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(Suppl 1):i82–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao M, Liu Y, Jin H, Liu X, Lv K, Wei H, Du C, Wang S, Wei B, Fu P. Prognostic value of preoperative inflammatory markers in Chinese patients with breast cancer. OncoTargets and therapy. 2014;7:1743–52. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S69657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asano Y, Kashiwagi S, Onoda N, Noda S, Kawajiri H, Takashima T, Ohsawa M, Kitagawa S, Hirakawa K. Predictive value of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio for efficacy of preoperative chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(4):1104–10. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4934-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azab B, Shah N, Radbel J, Tan P, Bhatt V, Vonfrolio S, Habeshy A, Picon A, Bloom S. Pretreatment neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is superior to platelet/lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of long-term mortality in breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):432. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia W, Wu J, Jia H, Yang Y, Zhang X, Chen K, Su F. The peripheral blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is superior to the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio for predicting the long-term survival of triple-negative breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0143061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh CH, Bhoo-Pathy N, Ng KL, Jabir RS, Tan GH, See MH, Jamaris S, Taib NA. Utility of pre-treatment neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic factors in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(1):150–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patnaik J, Byers T, DiGuiseppi C, Dabelea D, Denberg T. Cardiovascular disease competes with breast cancer as the leading cause of death for older females diagnosed with breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(3):R64. doi: 10.1186/bcr2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdel-Qadir H, Austin PC, Lee DS, et al. A population-based study of cardiovascular mortality following early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Cardiol. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah N, Parikh V, Patel N, Patel N, Badheka A, Deshmukh A, Rathod A, Lafferty J. Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio significantly improves the Framingham risk score in prediction of coronary heart disease mortality: insights from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey-III. Int J Cardiol. 2014;17(3):390–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Larco J, Wuertz B, Furcht L. The potential role of neutrophils in promoting the metastatic phenotype of tumors releasing interleukin-8. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(4):895–900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Hag A, Clark R. Immunosuppression by activated human neutrophils. Dependence on the myeloperoxidase system. J Immunol. 1987;139(7):2406–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loi S, Sirtaine N, Piette F, Salgado R, Viale G, Van Eenoo F, Rouas G, Francis P, Crown JP, Hitre E, de Azambuja E, Quinaux E, Di Leo A, Michiels S, Piccart MJ, Sotiriou C. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02-98. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(7):860–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srikanthan A, Bedard PL, Goldstein S, Templeton A, Amir E. Association between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the 21-gene recurrence score. Cancer Research Conference: 38th Annual CTRC AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium San Antonio, TX, USA. Conference Start. 2016;76(4 Suppl 1). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS15-P2-08-05

- 23.Azab B, Bhatt VR, Phookan J, Murukutla S, Kohn N, Terjanian T, Widmann WD. Usefulness of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in predicting short- and long-term mortality in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(1):217–24. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bozkurt O, Karaca H, Berk V, Inanc M, Duran AO, Ozaslan E, Ucar M, Ozkan M. Predicting the role of the pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in the survival of early triple-negative breast cancer patients. J BUON. 2015;20(6):1432–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dirican A, Kucukzeybek BB, Alacacioglu A, Kucukzeybek Y, Erten C, Varol U, Somali I, Demir L, Bayoglu IV, Yildiz Y, Akyol M, Koyuncu B, Coban E, Ulger E, Unay FC, Tarhan MO. Do the derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predict prognosis in breast cancer? Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20(1):70–81. doi: 10.1007/s10147-014-0672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noh H, Eomm M, Han A. Usefulness of pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in predicting disease-specific survival in breast cancer patients. J Breast Cancer. 2013;16(1):55–9. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pistelli M, De Lisa M, Ballatore Z, Caramanti M, Pagliacci A, Battelli N, Santinelli A, Biscotti T, Berardi R, Cascinu S. Pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio may be an useful tool in predicting survival in early triple-negative breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 Suppl 1):195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Rimando J, Campbell J, Kim JH, Tang SC, Kim S. The pretreatment neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is associated with all-cause mortality in black and white patients with non-metastatic breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2016;6(81). http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2016.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Hong J, Mao Y, Chen X, Zhu L, He J, Chen W, Li Y, Lin L, Fei X, Shen K. Elevated preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts poor disease-free survival in Chinese women with breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;21:21. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Detailed characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 4 in Appendix 2.