Abstract

Background

Nest selection is widely regarded as a key process determining the fitness of individuals and viability of animal populations. For marine turtles that nest on beaches, this is particularly pivotal as the nesting environment can significantly control reproductive success.The aim of this study was to identify the environmental attributes of beaches (i.e., morphology, vegetation, urbanisation) that may be associated with successful oviposition in green and loggerhead turtle nests.

Methods

We quantified the proximity of turtle nests (and surrounding beach locations) to urban areas, measured their exposure to artificial light, and used ultra-high resolution (cm-scale) digital surface models derived from Structure-from-Motion (SfM) algorithms, to characterise geomorphic and vegetation features of beaches on the Sunshine Coast, eastern Australia.

Results

At small spatial scales (i.e., <100 m), we found no evidence that turtles selected nest sites based on a particular suite of environmental attributes (i.e., the attributes of nest sites were not consistently different from those of surrounding beach locations). Nest sites were, however, typically characterised by occurring close to vegetation, on parts of the shore where the beach- and dune-face was concave and not highly rugged, and in areas with moderate exposure to artificial light.

Conclusion

This study used a novel empirical approach to identify the attributes of turtle nest sites from a broader ‘envelope’ of environmental nest traits, and is the first step towards optimizing conservation actions to mitigate, at the local scale, present and emerging human impacts on turtle nesting beaches.

Keywords: Citizen science, Geo-morphometry, Beach vegetation, Nest attributes, Conservation

Introduction

Death is now the phoenix’ nest;

And the turtle’s loyal breast

To eternity doth rest,

From: “The Phoenix and the Turtle”

by William Shakespeare (Harrison, 1966).

Habitat selection is a universal biological process in which individuals actively identify and inhabit sub-sections of a broader habitat to increase fitness (Fuentes et al., 2010; Morris, 2011; Schlacher, Meager & Nielsen, 2014). Nest-site selection is a key component of habitat selection (Jones, 2001; Morris, 2011; Schlacher, Meager & Nielsen, 2014), with nest position often resulting from trade-offs that are made by adults to maximise their own survivorship and optimise the fitness of their offspring (Nilsson, 1984; Martin & Roper, 1988; Fuentes, Limpus & Hamann, 2011).

Marine turtles are emblematic flagship species in biological conservation, being threatened globally by the cumulative pressures of harvesting, habitat modification, pollution, and climate change (Kamrowski et al., 2014; Roe et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2014; Fuentes et al., 2015; Jeffers & Godley, 2016). Adult female turtles deposit their eggs in shallow nests on the dunes of sandy beaches, and are believed to select nesting locations to minimise predation risk and to optimise reproductive success (Nel, Punt & Hughes, 2013). The attributes of nest sites control the thermal environment for the developing eggs (Booth & Astill, 2001; Fuentes et al., 2009), and also modify both predation risk and access to the ocean for emerging hatchlings (Mousseau & Fox, 1998; Wood, Bjorndal & Ross, 2000; Putman, Bane & Lohmann, 2010a; Limpus & Kamrowski, 2013). Female turtles may also choose nest positions to minimise their energy expenditure and maximise the ease with which they can return to the sea, thereby increasing the probability of inundation for nests that are constructed lower on beaches (Kamel & Mrosovsky, 2004; Pfaller, Limpus & Bjorndal, 2009). Adult marine turtles provide no post-ovipositional care to their offspring, and so cannot modify nest attributes to compensate for poorly selected nest sites, or changes to the environment near the nest that occur after oviposition (Wood, Bjorndal & Ross, 2000). Consequently, the environmental attributes of nest sites play a critical role in determining hatching success, and in modifying the fitness and survivorship of turtle hatchlings (Mitchell, Warner & Janzen, 2013).

Marine turtles are thought to select nest sites according to a hierarchy of environmental factors operating across a range of spatial scales (Table 1) (Wood, Bjorndal & Ross, 2000; Roe, Clune & Paladino, 2013). At regional scales (10s km), the choice of nest position is thought to be largely determined by variations in weather and oceanographic conditions, as well as the natal homing behaviour of individuals (i.e., philopatry) (Putman, Shay & Lohmann, 2010b; Pike, 2013a; Brothers & Lohmann, 2015). At the scale of individual beaches (100s m), it has been hypothesized that nest site selection by females may be influenced by local environmental conditions, including beach morphology (Wood, Bjorndal & Ross, 2000; Cuevas, de los Ángeles Liceaga-Correa & Mariño-Tapia, 2010), dune vegetation (Turkozan, Yamamoto & Yilmaz, 2011), and sediment attributes (i.e., grain size, sand temperature) (Wood, Bjorndal & Ross, 2000; Fuentes et al., 2010). Despite the widely-cited and hypothesized role of these environmental factors in putatively influencing nesting turtles, it is rare for studies to examine the influence of multiple environmental attributes, making robust attribution and inferences about the relative importance of individual factors difficult or impossible. Furthermore, there is high intra- and interspecific variation in observed relationships between nest position and the highly dynamic features of beaches and their surf-zones (Hamann, Limpus & Owens, 2002; Miller, Limpus & Godfrey, 2003; Liles et al., 2015). Thus, there are no universally accepted and robust models to predict how the environmental attributes of nesting beaches determine nest selection by nesting marine turtles (Liles et al., 2015; Santos et al., 2015).

Table 1. Summary of studies assessing the contribution of different environmental factors to the selection and attributes of marine turtle nests.

Specifying species studied, the reported relationship, number of studies the feature was included in and key references.

| Environmental factor(s) | Speciesa | Reported general relationship with nest placement | No. studiesb | Key reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intertidal beach | ||||

| Slope | LH, GT, HB, OR, LB | Highly variable relationship between angle of the beach and nest density or frequency with no consistent pattern. Variability is evident among species and populations, tending to be rookery habitat specific | 11 (10) | Garmestani et al. (2000), Wood, Bjorndal & Ross (2000), Fish et al. (2005), Ficetola (2007), Spanier (2009), Cuevas, de los Ángeles Liceaga-Correa & Mariño Tapia (2010), Katselidis et al. (2013b) and Roe, Clune & Paladino (2013) |

| Width | GT, HB, LH, OR | Highly variable, with evident preferences for both wide and narrow beaches and beach sections. Variability is evident among species and populations, tending to be rookery habitat specific | 8 (6) | Kikukawa, Kamezaki & Ota (1999), Garmestani et al. (2000), Mazaris, Matsinos & Margaritoulis (2006), Cuevas, de los Ángeles Liceaga-Correa & Mariño Tapia (2010), Witherington, Hirama & Mosier (2011), Katselidis et al. (2013b) and Barik et al. (2014) |

| Elevation | LH, HB | Positive correlation with nest density for LH and HB, nesting consistently occurred at a specific elevation. | 3 (3) | Horrocks & Scott (1991), Kikukawa, Kamezaki & Ota (1999) and Katselidis et al. (2013a) |

| Topography | LH, GT | Positive correlation with uneven beach topography for GT, with nest excavation believed to be initiated by the presence of the uneven beach zone above the spring high tide line. | 1 (1) | Hays et al. (1995) |

| Ordinal aspect | LH, HB | Not significant | 1 (0) | Garmestani et al. (2000) |

| Dune | ||||

| Silhouette | LH | Higher emergences on beach sections where dunes have a distinct and/or higher silhouette. | 5 (4) | Camhi (1993), Hays & Speakman (1993); Salmon & Witherington (1995), Mazaris, Matsinos & Margaritoulis (2006) and Witherington, Hirama & Mosier (2011) |

| Slope | HB, GT | Not significant | 1 (0) | Cuevas, de los Ángeles Liceaga-Correa & Mariño Tapia (2010) |

| Sediment | ||||

| Grain size | OR, LB, LH, GT | Nest density is positively correlated with medium-sized grains for OR, intermediate size classes for LB, and large particle size classes for LH. LH and LB fewer nests in areas with silty sediment). GT nesting in a range of sediment grain sizes. | 5 (4) | Horrocks & Scott (1991), Garmestani et al. (2000), Wood, Bjorndal & Ross (2000), Karavas et al. (2005), Roe, Clune & Paladino (2013) and Barik et al. (2014) |

| Sorting | LH, OR | Higher nest density in areas with well-sorted sand grains. | 3 (3) | Mazaris, Matsinos & Margaritoulis (2006), Chen, Cheng & Hong (2007) and Barik et al. (2014) |

| Compaction | HB, LH, GT | HB and LH nest density positively correlated with lower sand compaction, with higher rates of nest abandonment in areas of highly compacted sands. GT nest density higher in areas with higher compaction (i.e., 10–30% vegetation cover) compared to opened sand areas, but lower sand compaction compared to vegetated areas > 40% cover | 3 (3) | Kikukawa, Kamezaki & Ota (1999), Chen, Cheng & Hong (2007) and Ficetola (2007) |

| Temperature | LH | The role of temperature in nest selection is unclear. Stoneburner & Richardson (1981) reported that the rapid increase in surface sand temperature along the water-to-dune axis initiated nesting of loggerhead turtles; however, this was later identified as an artefact of their sampling method (refer to Hays et al., 1995; Wood, Bjorndal & Ross, 2000). | 4 (1) | Stoneburner & Richardson (1981), Horrocks & Scott (1991), Hays et al. (1995) and Wood, Bjorndal & Ross (2000) |

| Moisture | LH, GT | Successful nesting attempts in GT associated with higher sand moisture, while unsuccessful nesting attempts in drier sand. | 5 (1) | Bustard & Greenham (1968), Garmestani et al. (2000), Wood, Bjorndal & Ross (2000) and Chen, Cheng & Hong (2007) |

| Salinity | LH, LB | Significant factor only for LB, showing a negative correlation with nest density. | 2 (1) | Karavas et al. (2005); Roe, Clune & Paladino (2013) |

| pH | LH, LB, GT, HB | Highly variable relationship between nesting and pH: positive in LB, negative in HB, no association in GT. | 4 (2) | Garmestani et al. (2000), Karavas et al. (2005), Mazaris, Matsinos & Margaritoulis (2006) and Barik et al. (2014) |

| Organic content | LB, LH | Not significant | 4 (0) | Horrocks & Scott (1991), Karavas et al. (2005), Mazaris, Matsinos & Margaritoulis (2006) and Roe, Clune & Paladino (2013) |

| Calcium carbonate content | LH | Nesting density positively correlated with low calcium carbonate content. | 1 (1) | Garmestani et al. (2000) |

| Rock cover | HB | Nesting positively correlated with low rock cover and higher nest abandonments in areas with higher rock cover. | 1 (1) | Ficetola (2007) |

| Vegetation | ||||

| Cover | LH, GT, HB, LB, OR | Significant factor, however, the nature of the relationship varies greatly among populations. LH and OR population’s preferred bare sand areas, generally aborting nesting attempts in vegetation cover. A single study identified successful nesting in vegetation for LH but at a lower density to open sand nesting. LB nesting density is higher on bare sand or negligible vegetation cover. GT nest density is higher in the vegetated zones (particularly in 10–30% vegetation cover), nesting still occurs on the un-vegetated zone of beach but to a lesser degree. HB nesting density highest in dense shrub coverage. | 11 (11) | Hays & Speakman (1993), Hays et al. (1995), Kikukawa, Kamezaki & Ota (1999), Kamel & Mrosovsky (2004), Karavas et al. (2005), Mazaris, Matsinos & Margaritoulis (2006), Chen, Cheng & Hong (2007), Ficetola (2007), Serafini, Lopez & Da Rocha (2009), Turkozan, Yamamoto & Yilmaz (2011) and Hart et al. (2014) |

| Canopy cover (%) | HB | HB population in the West Indies selected a variety of canopy cover, with significant individual repeatability in the percentage of canopy cover used. While, HBs of El Salvador and Nicaragua had strong population preferences for abundant over story vegetation cover (84.1% and 92.5%, respectively) | 3 (3) | Kamel & Mrosovsky (2005), Kamel & Mrosovsky (2006) and Liles et al. (2015) |

| Species composition | LH, HB | LH did not nest in vegetated zones of the beach, which were dominated by woody shrubs and trees, though some nesting (10/180 nests) occurred in areas of low-lying vegetation with rhizomes. HB show individual preferences for vegetation coverage of low lying grass and tall woody vegetation | 5 (4) | Garmestani et al. (2000), Kamel & Mrosovsky (2005), Karavas et al. (2005) and Kamel & Mrosovsky (2006) |

Notes.

LH, Loggerhead; GT, Green turtle; LB, Leatherback; HB, Hawksbill; OR, Olive ridley.

Number of studies that report statistically significant relationships between nesting density/frequency and a particular environmental factor is given in brackets.

Anthropogenic impacts, foremost coastal urbanization and climate change, are altering the structure and function of sandy beaches at unprecedented scales and intensities (Schlacher et al., 2007; Schoeman, Schlacher & Defeo, 2014; Schlacher et al., 2015; Schlacher et al., 2016), and may have changed the quality of many sandy beaches as a nesting habitat for marine turtles (Mazaris, Matsinos & Pantis, 2009; Pike, 2013a; PCC, 2014). Artificial night-light can alter the behaviour of female turtles that emerge to nest on beaches where the light environment is significantly changed (Salmon & Witherington, 1995; Mazaris, Matsinos & Pantis, 2009). Artificial lights can disorient hatchlings and increase the risk of predation (Limpus & Kamrowski, 2013; Rivas et al., 2015; Thums et al., 2016). Many urban beaches have seawalls and are being artificially nourished with sand, detrimentally affecting nesting female turtles and hatchlings (Brock, Reece & Ehrhart, 2009; Rizkalla & Savage, 2010; Fujisaki & Lamont, 2016).

Many populations of marine turtles are of significant conservation concern, requiring multiple management interventions (Harris et al., 2015). One approach (in the broader conservation toolkit for marine turtles) is to actively manage beach- and dune-scapes to optimize conditions for nesting by protecting areas with favourable nest site attributes. To do this, one first requires empirical data on the features of beaches that are characteristic of turtle nests, and therefore represent locations that are likely to be suitable nesting sites. In this context, the chief aim of this study is to identify the environmental features of nesting beaching that are associated with successful turtle oviposition. To this end, we measured a broad suite of local environmental attributes derived from geo-morphometric techniques based on ultra-high resolution digital surface models and imagery. By applying these novel techniques, we introduce two new geomorphic factors to the study of nest site selection in marine turtle research: terrain ruggedness and beach profile curvature. We then test whether these environmental features of the beach- and dune face are associated with nest sites.

Methods

Study area

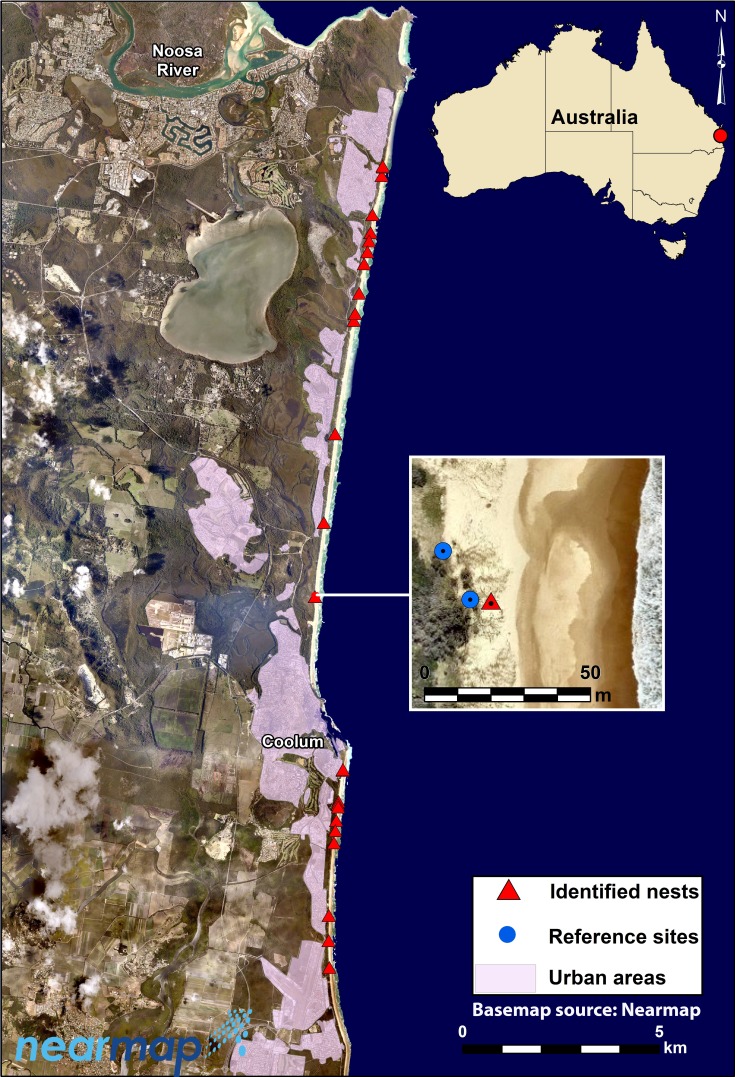

Turtle nest-site attributes were measured along 26 km of exposed ocean beaches on the northern Sunshine Coast in south-east Queensland, Australia (∼26°30′S, 153°6′E) (Fig. 1). These beaches are mostly of the intermediate morphodynamic type (sensu Short & Jackson, 2013), and are micro-tidal (typical range <2 m) with moderate to high waves (significant wave height 0.5–2 m) from prevailing south-easterly winds (Schlacher & Thompson, 2012; Schlacher et al., 2015). Landward development consists mostly of peri-urban to sub-urban private dwellings built on, or behind, a vegetated dune system with an average width of 100–150 m and height of ∼10 m above mean sea level. For the purposes of this study, urban areas are defined as contiguous land cover or land composed of impervious surfaces that include housing, buildings, and other anthropogenic infrastructure such as roads (Huijbers et al., 2015).

Figure 1. Map of study area on the northern Sunshine Coast in south-east Queensland, Australia.

Map shows the location of the 19 nest sites, digitized urban areas, and an insert map illustrating the random ‘reference sites’ measured in this study in the vicinity of a nest site (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2014).

In this region, nesting occurs primarily from early November to mid-February mainly by loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) and, to a lesser extent, by green turtles (Chelonia mydas) (Limpus, 2008; Limpus & Fien, 2008). The number of loggerhead turtle nests in the region varies from 4 to 30 confirmed nest locations per season (Coolum Coast Care & I Kelly, pers. comm., 2014). Overall, the number of nesting loggerhead females on the northern Sunshine Coast represents approximately 0.15–1.11% of the Australian east coast population (approximately 2,700 individuals; Limpus & Limpus, 2003; Kamrowski et al., 2014). Green turtle nests are less common, with fewer than 5 nests recorded each nesting season on this particular stretch of coast. Whilst the beaches of the Sunshine Coast currently only support a comparatively small part of the nesting population of marine turtles on the East Coast of Australia, the region may be at the leading edge of predicted species range shifts associated with climate change and hence become more important for nesting turtles in the future.

During this study, nests were located by the tracks made by female turtles when crossing the beach and dunes. Citizen scientists from a local community group (Coolum Coast Care) monitored all beaches daily from early November 2014 to late February 2015: we are confident that all nests were successfully located along the northern Sunshine Coast beaches within this period.

Within two hours following detection of tracks by volunteers, we measured a suite of variables at turtle nests in which eggs were successfully deposited, and at two random reference sites within a 50 m radius of each nest. We determined the position of random reference sites using a random number generator in ArcGIS 10.2 (ESRI, 2013), but stipulated that they must occur at least 5 m from a known nest site. These reference sites at which turtles did not attempt to construct nests, therefore, constitute a suite of locations where environmental conditions are theoretically appropriate for turtle nesting, but where no turtle nested during our study.

Terrain data collection

Ultra-high spatial resolution (cm-scale) image orthomosaics and digital surface models (DSMs) of the beach and dune areas surrounding observed nests (∼50 m) were derived by close-range photogrammetry and Structure from Motion (SfM) algorithms. SfM semi-automated photogrammetric technique is useful for obtaining ultra-high resolution datasets and 3D information from 2D images (Leon et al., 2015). The technique is now used in a diverse range of applications, including quantifying geomorphic features on sandy beaches (Mancini et al., 2013; Chikhradze et al., 2015). SfM works by using a set of overlapping 2D digital images and matches single features in multiple images to reconstruct 3D geometry (Westoby et al., 2012; Mancini et al., 2013).

Images were obtained with a digital camera (Canon PowerShot D30, 12.1 megapixels, ∼AU$300), programmed to take images every second using the Canon Hack Development Kit (http://chdk.wikia.com/wiki/CHDK). The camera was mounted on an 8 m pole and tilted obliquely at a 30° angle to reduce systematic broad-scale errors (i.e., “doming” effect) in the topographic reconstructions (James & Robson, 2014). The camera was carried by the first author walking a series of parallel, overlapping transects up and down the width of the beach, within a quadrat set at ∼50 m by the length of the beaches width (max area covered 250 m2) and encompassing the nest itself. Accurate SfM requires at least 70% overlap between images and at least three consecutive images within which a given feature (i.e., key point) is visible (Westoby et al., 2012). Each image produced a footprint of 10 × 7 m at a height of 8 m, so each image and every transect line were separated by a maximum of 3 m. Five ground-control points (GCPs; discs marked with two 20 cm scale bars) were placed at the corners and middle of the surveyed quadrat and their location recorded using a handheld Garmin eTrex 10 GPS (horizontal accuracy < 2 m). These ground-control points were used to geo-reference the cameras’ absolute position (i.e., object-space coordinates). Seven additional GCPs were randomly distributed across the quadrat and were used for precise scaling and optimization (relative position) of the 3D model and image orthomosaic.

Agisoft PhotoScan Professional edition v1.1 software was used to create the DSMs and image orthophoto mosaics based on SfM algorithms. Processing involved four main steps: (1) image triangulation, (2) optimization, (3) dense surface reconstruction, and (4) orthophoto generation. The products were georeferenced to GDA94 MGA56 coordinate systems and the resulting orthophoto mosaics and the DSMs were exported with a 1 cm and a 10 cm spatial resolution, respectively.

For comparison purposes, a detailed validation was undertaken at one of the nest locations based on 32 independent, randomly placed ground-control points (GDA94 MGA 56 horizontal coordinate system, AHD vertical datum) surveyed across the quadrat boundary using a high-precision Global Navigation Satellite System (CHC X91+ system with nominal accuracy of 10 mm and 15 mm in horizontal and vertical positions, respectively). The models have a high precision with an average relative accuracy of 0.01 m (horizontal and vertical) as calculated from the used markers and scales. Only one of the models was validated independently for absolute accuracy using a high-precision real time differential GPS. The results showed an average elevation error (absolute accuracy) of 0.22 m from the Australian Height Datum.

Nest site attributes

Beach geomorphic features were extracted from the SfM-derived DSMs. Terrain analysis was performed using SAGA GIS 2.0 (Cimmery, 2010) to obtain profile curvature (Romstad & Etzelmüller, 2012) and terrain ruggedness (Sappington, Longshore & Thompson, 2007). In total, we measured 11 attributes for each nest and reference site; a full description of all metrics used to define nest attributes is given in Table 2.

Table 2. List of the environmental and anthropogenic features and nest attributes measured in this study.

| Measured features and attributes | Units | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental features | |||

| Slope of subaerial beach and dune face | Degrees | Subaerial beach slope was measured between the observed high-water line and the dune toe perpendicular to the nest sites. Dune slope was measured between the dune toe and the dune crest perpendicular to the nest sites. All distance and elevation were measured using ArcGIS10.2. | Zevenbergen & Thorne (1987), ESRI (2013) |

| Beach profile curvature | Radians per m | Curvature is the second derivative of elevation (i.e., the slope of the slope) calculated using the SfM-DEM. Profile curvature is the curvature intersecting with the plane defined by the Z-axis and maximum gradient direction. Positive values describe convex profile curvature; negative values concave profile and zero values flat surface. Calculated using SAGA GIS 2.1 as implemented in the Morphometry Features tool using a 5 ×5 m window. | Wood, Bjorndal & Ross (2000); Romstad & Etzelmüller (2012) |

| Terrain ruggedness | Standardised index | Terrain ruggedness was calculated using the vector ruggedness measure (VRM), a parameter that minimizes correlation with slope, based on the SfM-DEM. The dimensionless ruggedness number ranges from 0 (flat) to 1 (most rugged). Calculated in SAGA GIS as implemented in the Morphometry Features tool using a 5 ×5 m window. | Sappington, Longshore & Thompson (2007) |

| Width of the Subaerial beach and dune | m | The subaerial beach was defined between the observed high-water line and the dune toe perpendicular to nest sites. The dune face was defined between the dune toe and dune crest perpendicular to nest sites. Measured using ArcGIS 10.2 | ESRI (2013) |

| Distance of nest from dense vegetation | m | The Euclidean distance from the nearest digitized dense vegetation cover to the nest as implemented in ArcGIS 10.2. | Hunt et al. (2005); ESRI (2013) |

| Distance of nest from sparse vegetation | m | The Euclidean distance from the nearest digitized sparse vegetation cover to the nest as implemented in ArcGIS 10.2. | Hunt et al. (2005); ESRI (2013) |

| Anthropogenic features | |||

| Distance to urban areas | m | Euclidean distance from nearest urban area (i.e., contiguous land cover/land composed of relatively dense coverage of impervious surfaces that include housing and other anthropogenic infrastructure) as implemented in ArcGIS 10.2. | ESRI (2013) |

| Exposure to artificial light | (mcd m2) | Manual light measurements using a hand-held night sky brightness photometer, Unihedron Sky Quality Meter-L. Light was measured as magnitudes per square arcsecond (mag/arcsec2) and converted to milicandelea per square meter (mcd m2). | Cinzano & Falchi (2014) |

SfM-derived image orthophoto mosaics were used to manually digitize beach and dune geomorphic features including the dune crest, dune toe, and the observed high-water line (proxy for high tide waterline; Boak & Turner, 2005). The subaerial beach width and slope were measured between the observed high-water line and the dune toe perpendicular to the nest sites. Dune slope and width were measured between the dune toe and the dune crest perpendicular to the nest sites. All distance and elevation were measured using ArcGIS10.2.

Proximity analysis was used to calculate straight-line (Euclidean) distances between each nest and random points and the nearest urban area. These areas were manually digitized from a 2012 SPOT 5-satellite imagery (2.5 m spatial resolution) (See Fig. 1). Distance to vegetation cover on the dune and beach was also calculated in this way. Sparse and dense vegetation coverage was classified using a semi-automatic approach based on the SfM-derived image orthomosaics. Imagery consisted of only visible bands (i.e., red, green, blue), so the normalized green-red difference index (NGRDI) (Hunt et al., 2005) was preferred over conventional indices that require the near-infrared band. Vegetation cover was first classified by manually setting a threshold for the NRGDI images. Vegetation density was then determined by counting how many vegetation-classified pixels were located within 0.5 m2 “virtual” quadrats, derived using the Block Statistics tool in ArcGIS 10.2. Finally, vegetation density was classified into sparse (<50%) and dense (>50%) vegetation cover classes.

To identify whether nests and reference sites were exposed to artificial light sources, light measurements were taken with a hand-held night sky brightness photometer (Unihedron Sky Quality Meter-L.) This instrument responds to light with wavelengths in the range of 320–1050 nm, which covers the range marine turtles are known to respond to (i.e., 350–700 nm; Kamrowski et al., 2012). Light was measured as magnitudes per square arcsecond (mag/arcsec2) and converted to milicandelea per square meter (mcd/m2). This instrument was calibrated using a NIST-traceable light meter with an absolute precision of ±0.10 mag/arcsec2. Measurements were recorded at each nest and reference site facing towards the back of the dune. All measurements were taken at ‘turtle-height’ by crouching down and taking a reading about 5–10-cm above the sand surface at the uprush limit of the swash. A beach location, which had no visible sources of artificial light during a new moon period, had a light reading of ∼0.2–4 mcd m2 whereas a beach with visible artificial light had a reading of ∼7–14 mcd m2.

Data analyses

Our analyses tested three complementary questions: (1) What environmental conditions are typical of turtle nests; (2) Do the environmental characteristics of turtle nests differ from attributes of the broader dune-face and beach-face; and (3) Which parts of dunes and the upper beach are substantially different (i.e., highly distinct) in their environmental characteristics from nesting locations, and thus probably not suitable for turtle nesting in the future?

To characterise what constitutes the set of ‘typical’ nest site traits (Question 1), we used the similarity percentage (SIMPER) procedure in Primer 6.1.13 (Clarke, 1993) with normalised untransformed data to identify nest attributes that contribute most to the average similarity within the group of nest sites. To test whether nest sites have distinct environmental attributes relative to their nearby (<50 m) surroundings (Question 2), we used a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) calculated on a Euclidean distance resemblance matrix (Anderson, Gorley & Clarke, 2008) to contrast features of nest sites with random locations. PERMANOVA was complemented by PERMDISP (homogeneity of dispersions procedure) to test whether nests were more or less variable in multivariate environmental space than the set of reference sites (Anderson, Gorley & Clarke, 2008). Finally, to define areas that would–based on measured attributes of actual nest locations–presumably have a lower probability of successful nesting attempts (Question 3) we used group-average clustering based on Euclidean distances over the full set of environmental variables. Similarities between actual nests, random points within the mean centroid distance of nests, and ‘atypical’ locations were visualised with canonical analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) (Anderson & Willis, 2003). Given our restriction on random sample points being within a 50 m radius of nest sites, all analyses comparing nest-site and random-point attributes are considered to apply to primarily to local scales.

Due to the very low number of green turtle nests (n = 2) and diagnostic checks (PERMANOVA), not indicating substantial differences in nest attributes between species, we pooled loggerhead (n = 19) and green turtle nests for statistical analyses.

Results

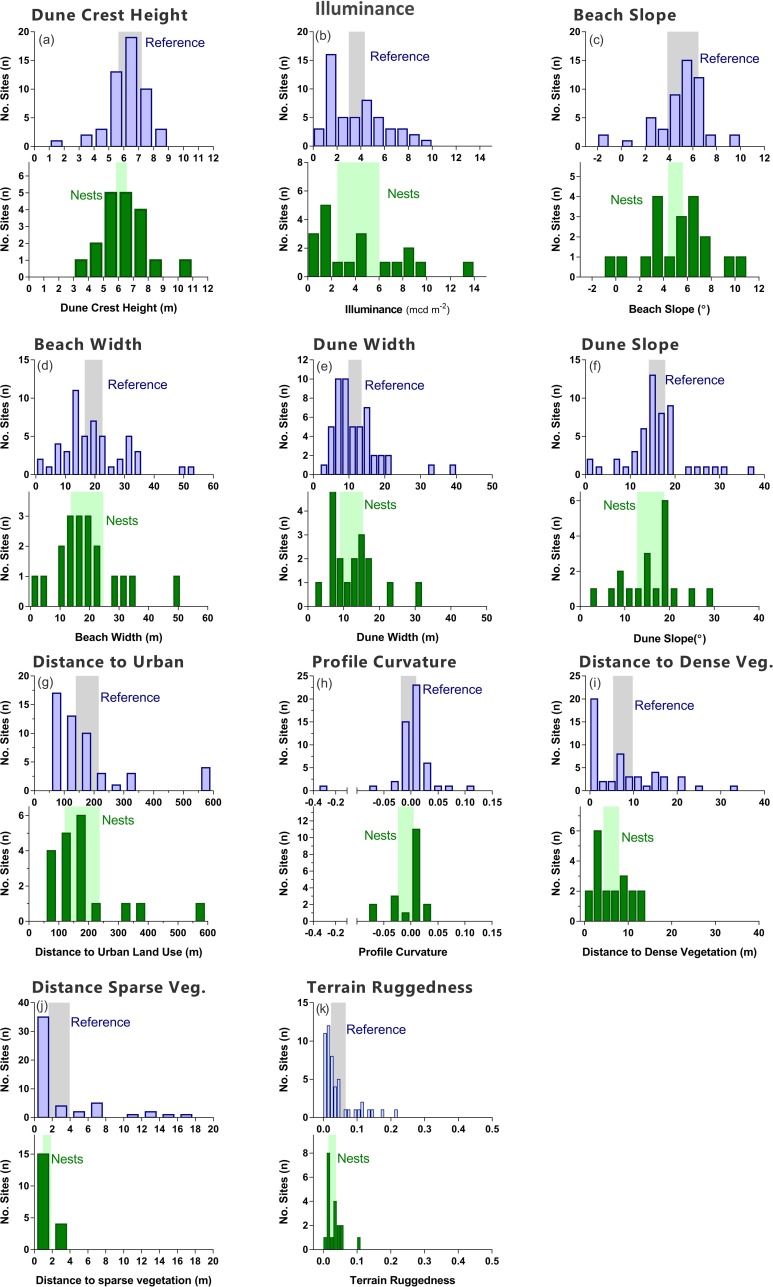

Environmental factors that explained most of the internal similarity within the group of successfully constructed nest sites were: (1) illuminance; (2) the height of the dune crest; and (3) beach slope (Table 3). Thus, turtles constructed nests on parts of the beach with illuminance values of 2.40–6.03 mcd m−2 (95% confidence interval), seawards of dunes that were 5.4–7.3 m high, and landwards of beaches that sloped between 3.5 and 6.7° (Table 3).

Table 3. SIMPER (Similarity Percentage) summary statistics.

Summary statistics of environmental attributes for observed turtle nest sites. SIMPER (Similarity Percentage) was based on a normalised untransformed data including all listed environmental variables.

| SIMPER | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (95% CI interval) | Range | Mean squared distance | Sq. dist./SD | Contribution % |

| Distance to sparse vegetation (m) | 1.42 (0.8–1.87) | 0–3.52 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 0.63 |

| Terrain ruggedness | 0.03 (0.01–0.04) | 0–0.10 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 1.36 |

| Distance to dense vegetation (m) | 6.12 (2.73–9.51) | 1.04–12.74 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 3.03 |

| Profile curvature (rad/m) | −0.01 (−0.04–0.01) | −0.11 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 4.43 |

| Distance to urban land use (m) | 178 (104–198) | 56–568 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 9.21 |

| Dune slope (deg) | 15.76 (10.69–19.19) | 3.72–28.75 | 0.95 | 0.48 | 10.21 |

| Dune width (m) | 12.18 (7.01–15.93) | 2.57–30.97 | 1.04 | 0.41 | 11.17 |

| Beach width (m) | 19.34 (12.29–22.96) | 2–50.3 | 1.07 | 0.41 | 11.44 |

| Beach slope (deg) | 5.16 (3.49–6.71) | −0.67–10.15 | 1.36 | 0.47 | 14.58 |

| Dune crest height (m) | 6.43 (5.38–7.34) | 3.28–10.54 | 1.43 | 0.43 | 15.36 |

| Illuminance (mcd m−2) | 4.26 (2.49–6.03) | 0.26–13.72 | 1.74 | 0.45 | 18.58 |

At small spatial scales (i.e., <100 m), we found no evidence that turtle nests occupy a distinct subset of the broader multi-dimensional geomorphic and vegetation niche present on the upper beach and the frontal dunes (i.e., nest sites did not differ significantly from reference sites) (Table 4, Fig. 2, PERMANOVA P = 0.931). Based on mean values of the environmental attributes of nest sites and reference sites, turtles dug nests on parts of the shore where the beach- and dune-face tended to be more concave and less rugged (Fig. 2). Nests were also located closer to vegetation, and in area with slightly higher illumination compared to reference sites (Fig. 2). Mean values for all remaining variables were indistinguishable between nests and reference sites (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of environmental features between actual nests sites of marine turtles and the full set of random locations sampled within a 50-m radius of each nest site.

| Variable | Nests | Reference | Nests | Reference | SIMPER | PERMANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% Confidence interval) | Mean (95% Confidence interval) | Median (Interquartile range) | Median (Interquartile range) | Average squared distance | Sq. dist./SD | Contrib. % | F | P | |

| Illuminance (mcd m2) | 4.26 (2.50–6.03) | 3.67 (2.99–4.34) | 3.48 (1.64–7.07) | 3.14 (1.56–5.31) | 2.42 | 0.66 | 11.69 | 0.63 | 0.46 |

| Dune crest height (m) | 6.43 (5.64–7.21) | 6.21 (5.85–6.56) | 6.33 (5.38–7.34) | 6.16 (5.61–7.01) | 2.22 | 0.61 | 10.75 | 0.36 | 0.57 |

| Beach slope (deg) | 5.16 (3.85–6.47) | 4.99 (4.37–5.61) | 5.63 (3.49–6.71) | 5.28 (4.19–6.13) | 2.17 | 0.66 | 10.47 | 0.07 | 0.79 |

| Beach width (m) | 19.34 (13.96–24.72) | 19.56 (16.53–22.59) | 17.70 (12.29–22.96) | 17.56 (12.7–24.91) | 1.99 | 0.62 | 9.61 | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| Dune width (m) | 12.18 (8.93–15.43) | 11.67 (9.81–13.53) | 10.64 (7.01–15.93) | 9.82 (7.6–14.62) | 1.98 | 0.53 | 9.56 | 0.08 | 0.79 |

| Dune slope (deg) | 15.76 (12.72–18.79) | 15.99 (14.14–17.83) | 16.07 (10.69–19.19) | 15.90 (12.83–18.5) | 1.92 | 0.62 | 9.28 | 0.02 | 0.90 |

| Distance to urban land use (m) | 178 (120–237) | 177 (139–215) | 151 (104–198) | 142 (90–192.8) | 1.86 | 0.52 | 9.01 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| Profile curvature (rad/m) | −0.0094 (−0.0239–0.0050) | −0.0047 (−0.0191–0.0098) | 0 (−0.04–0.01) | 0 (−0.01–0.01) | 1.61 | 0.25 | 7.77 | 0.17 | 0.71 |

| Distance to dense vegetation (m) | 6.12 (4.31–7.94) | 7.56 (5.32–9.80) | 4.91 (2.73–9.51) | 6.51 (0.2–13.45) | 1.55 | 0.59 | 7.50 | 0.57 | 0.45 |

| Distance to sparse vegetation (m) | 1.42 (0.99–1.85) | 2.78 (1.60–3.97) | 1.35 (0.80–1.87) | 0.89 (0.14–3.51) | 1.49 | 0.41 | 7.19 | 1.93 | 0.18 |

| Terrain ruggedness | 0.026 (0.015–0.038) | 0.044 (0.0227–0.0660) | 0.02 (0.01–0.04) | 0.02 (0.01–0.04) | 1.48 | 0.24 | 7.15 | 0.98 | 0.36 |

Figure 2. Histograms.

Comparison of environmental features between nests (green) and reference sites within 50 m of nests (blue). Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals.

The illuminance at the beach was the strongest environmental attribute contributing to both the internal similarity within the group of observed nest sites (Table 3), and to the difference between nests and the randomly selected reference sites (Table 4). The mean and median illuminance was slightly higher at nest sites (meannest/meanreference = 1.16; mediannest/medianreference = 1.11), but it must be stressed that these differences are very small, statistically not significant, and show considerable overlap between nest and reference sites (Table 4). Likewise, there was no evidence that selected nest sites were consistently located on substantially darker parts of the beach when analysed at the local (<100 m) scale.

Variability in environmental features was slightly greater at reference sites than at nest sites (PERMDISP P = 0.36; distance to centroid: nests = 2.70 ± 0.25 se; reference = 3.06 ± 0.21 se; Table 5). Variation in distance to vegetation (dense and sparse cover) was significantly (P < 0.05) greater at reference sites than nest sites (Table 5). Nests were positioned at sites that were slightly, but not significantly, more variable in beach illuminance than reference sites (i.e., illuminance range = 0.26–13.72 mcd m2; P = 0.07; Table 5).

Table 5. Test of the multivariate homogeneity variance in environmental features between turtle nest sites and reference sites.

Summary of PERMDISP, testing the multivariate homogeneity of variance in environmental features between turtle nest sites and reference sites within 50 m of nests.

| Variable | PERMDISP (df 1, 68) | Distance from centroid nests | Distance from centroid reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | |

| Distance to dense vegetation (m) | 7.84 | 0.01 | 3.24 | (0.40) | 6.35 | (0.66) |

| Distance to sparse vegetation (m) | 13.46 | 0.02 | 0.69 | (0.13) | 3.09 | (0.40) |

| Illuminance (mcd m2) | 4.47 | 0.07 | 1.04 | (0.18) | 0.74 | (0.07) |

| Terrain ruggedness | 3.99 | 0.20 | 0.02 | (<0.01) | 0.05 | (0.01) |

| Dune crest height (m) | 1.52 | 0.22 | 1.22 | (0.24) | 0.93 | (0.12) |

| Beach slope (deg) | 1.71 | 0.24 | 2.11 | (0.38) | 1.57 | (0.21) |

| Dune slope (deg) | 0.18 | 0.69 | 4.87 | (0.87) | 4.35 | (0.68) |

| Distance to urban land use (m) | 0.18 | 0.77 | 80.37 | (20.64) | 91.55 | (14.01) |

| Dune width (m) | 0.13 | 0.77 | 5.18 | (0.95) | 4.74 | (0.64) |

| Beach width (m) | 0.07 | 0.83 | 7.77 | (1.79) | 8.28 | (0.95) |

| Profile curvature (red/m) | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.023 | (0.004) | 0.021 | (0.007) |

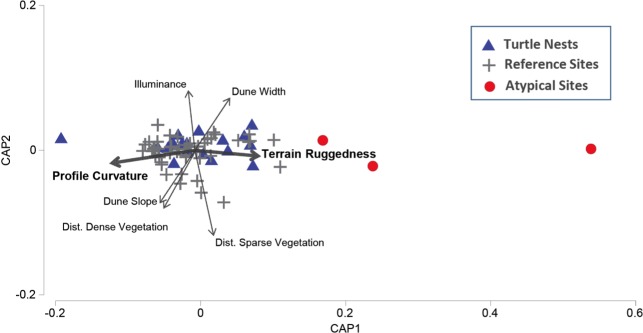

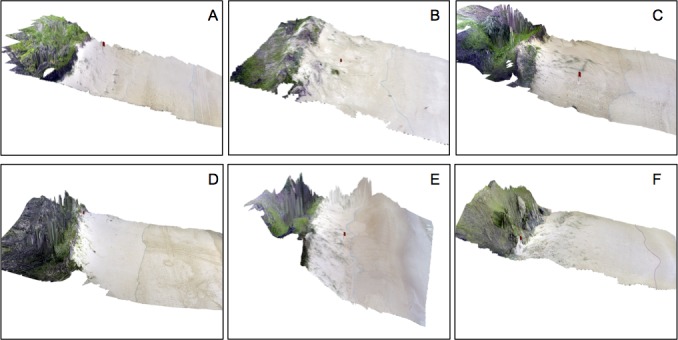

Three sites were identified to be distinctly different (i.e., ‘atypical’) to both nest sites and nearby reference sites (Fig. 3). Two ‘atypical’ sites were situated in dense plant cover and in areas characterised by highly rugged terrain (max terrain ruggedness 0.47), one of which was also positioned in a highly concave section of the dune face (profile curvature −0.324). An additional site was located on a very narrow and flat section of the beach (<3 m wide, slope < 0.15°), backed by a low and wide dune (crest height < 2 m, width 40 m) that had a flat frontal face (slope < 0.65°, profile curvature 0.007; Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Canonical Analysis of Principle Coordinates (CAP) ordination.

Illustrating patterns of similarity in the environmental features of nest sites (green circles), reference sites with similar environmental traits (grey crosses), and those characterized by environmental features that were ‘atypical’ of nest sites (P < 0.001) (red stars). Vector width is scaled to the level of correlation (Pearson) with the primary CAP axis.

Figure 4. 3D perspective of typical and atypical nesting beaches.

Typical (A–C) and atypical (D–F) nesting beaches based on CAP analysis with overlaid site locations (red flag) and digitised waterline (blue). Horizontal scale varies with perspective and vertical exaggeration is 1.5×.

Discussion

Recent improvements in the availability and application of remotely sensed data, coupled with new tools for geospatial analysis, provide novel insight into marine turtle nesting patterns and can assist with mapping putative anthropogenic threats to nesting turtles, such as artificial night light (Mazor et al., 2013) and the predicted consequences of seal-level rise (Fish et al., 2005; Fish et al., 2008). We used a combination of close-range photogrammetry and spatial analyses to create ultra-high resolution (cm-scale) terrain and imagery data just hours after turtles had nested. Our study introduces two new geomorphic features to the literature on marine turtle nesting–terrain ruggedness and profile curvature–and supports the importance of some variables (e.g., vegetation), whilst not finding support for others (e.g., urbanisation and illuminance). Nest sites were characterised by occurring close to vegetation, on parts of the shore where the beach- and dune-face was concave and not particularly rugged, and in areas with moderate exposure to artificial light. The environmental attributes of nest sites did, however, not differ significantly from those of surrounding beaches. This finding runs counter to our hypothesis and suggests that turtles might not select nest sites consistently at local scales (<100 m), or that attributes characterising ‘good’ nest sites for turtles were not measured by us. It is also possible that nest site selection may be weaker at or near the range edge of marine turtle nesting which is where our study beaches are located. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility of multiple nesting by the same female.

The cover of vegetation on dunes was a characteristic of successful nest sites, with most nesting (>90%) occurring in close proximity to vegetation (i.e., within 3.5 m of sparse, and with 13 m of dense vegetation). These findings concur with those of previous studies that report high nesting densities on open sand close to vegetation (Karavas et al., 2005; Chen, Cheng & Hong, 2007; Serafini, Lopez & Da Rocha, 2009; Turkozan, Yamamoto & Yilmaz, 2011; Hart et al., 2014; Katselidis et al., 2013b). The rate of nesting abandonment is, however, also generally highest in vegetated areas (Hays & Speakman, 1993; Karavas et al., 2005). In the study region, dune vegetation is dominated by spinifex grass (Spinifex longifolius), which has soft shallow roots that differ fundamentally from the tougher root systems of dune plants reported from other beaches (Hays & Speakman, 1993). Soft-rooted grasses bind sand grains, which helps provide suitable moisture and compactness levels for the construction of egg chambers (Chen, Cheng & Hong, 2007) and nest incubation (Hart et al., 2014). Marine turtles nest successfully near vegetation on numerous beaches, but the roots of dense vegetation also obstruct nest excavation, and so there is likely to be a threshold of vegetation cover above which nesting becomes futile (Chen, Cheng & Hong, 2007). On the beaches we studied, dense vegetation occurs mostly near the crest of dunes, and so we cannot exclude the possibility that vegetation effects on nesting turtles may be confounded with elevation effects.

The profile curvature and terrain ruggedness of beaches differed between nest sites and area of the surrounding beaches that were classified as ‘atypical’ of turtle nests. The relative concave profile of beaches surrounding nest sites may be associated with the proximity of dunes (i.e., beach profiles might dip prior to the dune toe). Alternatively, nests may be placed between embryo dunes near the foot of larger foredunes. Green turtles initiate nest excavation on parts of beaches where the terrain is rugged or uneven, whereas smoother beach profiles are linked to greater rates of nest abandonment (Hays et al., 1995). In our study, turtles constructed nests on sections of beaches with moderately rugged terrain; these values were, however, not significantly different to reference points on surrounding beach locations.

We found no significant effect of urban development (indexed by land conversion) on the location of turtle nests. Beaches in our study area were, however, less urbanized than those examined in other studies that report negative impacts of coastal development on turtle nesting (Weishampel et al., 2003; Kaska et al., 2010; Roe, Clune & Paladino, 2013). Previous studies examining this aspect have typically been conducted along nesting beaches backed by high-density beachfront infrastructure (Kaska et al., 2010; Roe, Clune & Paladino, 2013). By contrast, a distinct buffer of coastal vegetation (100–200 m wide) borders many beaches in our study area. Furthermore, no nesting was recorded during our study on beaches backed by seawalls. These structures modify beach profiles, near-shore bathymetry, and sand exchange (Mosier, 1998; Rizkalla & Savage, 2010), and are often associated with negative impacts on turtle nesting behaviour (Bouchard et al., 1998; Mosier & Witherington, 2002; Miller, Limpus & Godfrey, 2003). Beaches of the northern Sunshine Coast currently have only one short (<200 m) section of seawall, which contrasts with the large engineered seawalls that border many urbanised beaches in other parts of the world (Rizkalla & Savage, 2010).

Variation in wind direction and speed could, hypothetically, also influence nest site selection by turtles by changing surf conditions, particularly the strength and direction of longshore currents, the position of rips, and the number, period and height of breakers across the surf-zones (Lamont & Houser, 2014). Whilst all of these surf-zone properties could be important in determining the longshore position where turtles approaching the beach from the ocean cross the surf-zone, and ultimately crawl onto the beach to nest, there were outside the scope of the study. In fact, these factors have not been measured comprehensively in any other turtle nesting study anywhere.

Our finding of no significant correlation between turtle nest sites and artificial illuminance at the local scale (<100 m) was unexpected, as several studies have identified associations between artificial night light and nesting behaviour of turtles, generally postulating broad hypotheses that turtles may prefer darker beaches, or beach sections, for oviposition (Witherington, 1992; Kamrowski et al., 2012; Mazor et al., 2013). It is theoretically possible that the low influence of illuminance on small-scale nest selection found by us could be the result of nesting that occurred mostly during moonlit conditions. We do, however, consider this unlikely based on the dates when nests were constructed in relation to lunar phases: no nesting was observed during maximum full moon, three nests were laid three days either side of the full moon and one within four days. Furthermore, only two of the five nest sites exposed to artificial light were constructed during this time. The majority (79%) of nests were laid during a new, waxing, or waning moon. We postulate that the most parsimonious hypothesis for our findings is that any light effects on the nesting behaviour of turtles may operate at broader spatial scales than those examined by us (see also Mazor et al., 2013); we stress that this hypothesis remains to be tested, particularly the spatial ambit at which putative light impacts on nesting turtles may occur. Whilst we found no strong evidence for an effect of light on small-scale nest site selection by turtles, artificial night light cannot be excluded to influence turtle nest site selection at regional scales or in settings where contrasts between more brightly lit urban sectors and darker beach sections offer greater ‘contrast’ to make nesting decisions.

Effective turtle conservation is contingent on our ability to identify and manage nesting beaches (and beaches with potential as future nest sites; Hawkes et al., 2009; Fuentes, Limpus & Hamann, 2011; Pike, 2013b). This study outlines a method for completing the first step in this process using recently developed high-accuracy mapping techniques that will be useful in future predictive modelling of nesting habitats. From these models, we describe the environmental features of marine turtle nest sites on the Sunshine Coast and provide values for the most likely ‘envelope’ of preferred nest site conditions. Furthermore, by identifying environmental features that are highly distinct from nest sites, and presumably less suitable as nesting sites, we highlight opportunities where restoration can be conducted to enhance the suitability of beaches for turtle nesting. This information provides a baseline for identifying, predicting, and restoring stretches of the beach and dune scape that are most suitable as turtle nesting sites.

Supplemental Information

Spatial distribution of nest sites for 2008–2009 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2009–2010 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2010–2011 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2011–2012 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2012–2013 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2013–2014 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2015–2016 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Acknowledgments

We thank the dedicated volunteers from Coolum Coast Care who were instrumental in locating turtle nests and provided fantastic and invaluable support during the research. We also thank N Yabsley for field assistance, the sporting of a much-admired red beard, and comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors received no funding for this work.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Ilana Kelly conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Javier X. Leon conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Ben L. Gilby analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Andrew D. Olds contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Thomas A. Schlacher conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as Data S1.

References

- Anderson, Gorley & Clarke (2008).Anderson MJ, Gorley RN, Clarke KR. Permanova+ for primer: guide to software and statistical methods. PRIMER-E Ltd; Plymouth: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson & Willis (2003).Anderson MJ, Willis TJ. Canonical analysis of principal coordinates: a useful method of constrained ordination for ecology. Ecology. 2003;84:511–525. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[0511:CAOPCA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barik et al. (2014).Barik SK, Mohanty PK, Kar PK, Behera B, Patra SK. Environmental cues for mass nesting of sea turtles. Ocean & Coastal Management. 2014;95:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Boak & Turner (2005).Boak EH, Turner IL. Shoreline definition and detection: a review. Journal of Coastal Research. 2005;21:688–703. [Google Scholar]

- Booth & Astill (2001).Booth DT, Astill K. Incubation temperature, energy expenditure and hatchling size in the green turtle (Chelonia mydas), a species with temperature-sensitive sex determination. Australian Journal of Zoology. 2001;49:389–396. doi: 10.1071/ZO01006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard et al. (1998).Bouchard S, Moran K, Tiwari M, Wood D, Bolten A, Eliazar P, Bjorndal K. Effects of exposed pilings on sea turtle nesting activity at Melbourne Beach, Florida. Journal of Coastal Research. 1998;14:1343–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Reece & Ehrhart (2009).Brock KA, Reece JS, Ehrhart LM. The effects of artificial beach nourishment on marine turtles: differences between loggerhead and green turtles. Restoration Ecology. 2009;17:297–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2007.00337.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers & Lohmann (2015).Brothers JR, Lohmann KJ. Evidence for geomagnetic imprinting and magnetic navigation in the natal homing of sea turtles. Current Biology. 2015;25:392–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustard & Greenham (1968).Bustard HR, Greenham P. Physical and chemical factors affecting hatching in the green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas (L.) Ecology. 1968:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Camhi (1993).Camhi M. PhD thesis. 1993. The role of nest site selection in loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) nest success and sex ratio control. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Cheng & Hong (2007).Chen H-C, Cheng I-J, Hong E. The influence of the beach environment on the digging success and nest site distribution of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas, on Wan-an Island, Penghu Archipelago, Taiwan. Journal of Coastal Research. 2007;23:1277–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Chikhradze et al. (2015).Chikhradze N, Henriques R, Elashvili M, Kirkitadze G, Janelidze Z, Bolashvili N, Lominadze G. Close range photogrammetry in the survey of the coastal area geoecological conditions (on the Example of Portugal) Earth Sciences. 2015;4:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cimmery (2010).Cimmery V. SAGA User Guide, updated for SAGA version 2.0.5 2010.

- Cinzano & Falchi (2014).Cinzano P, Falchi F. Quantifying light pollution. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer. 2014;139:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke (1993).Clarke KR. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Australian Journal of Ecology. 1993;18:117–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1993.tb00438.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, de los Ángeles Liceaga-Correa & Mariño-Tapia (2010).Cuevas E, de los Ángeles Liceaga-Correa M, Mariño-Tapia I. Influence of beach slope and width on hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) and green turtle (Chelonia mydas) nesting activity in El Cuyo, Yucatan, Mexico. Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2010;9:262–267. doi: 10.2744/CCB-0819.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ESRI (2013).ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.2. Redlands: Environmental Systems Research Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ficetola (2007).Ficetola GF. The influence of beach features on nesting of the Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Arabian Gulf. Oryx. 2007;41:402–405. [Google Scholar]

- Fish et al. (2005).Fish MR, Cote IM, Gill JA, Jones AP, Renshoff S, Watkinson AR. Predicting the impact of sea-level rise on caribbean sea turtle nesting habitat. Conservation Biology. 2005;19:482–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00146.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fish et al. (2008).Fish M, Cote I, Horrocks J, Mulligan B, Watkinson A, Jones A. Construction setback regulations and sea-level rise: mitigating sea turtle nesting beach loss. Ocean & Coastal Management. 2008;51:330–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2007.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes et al. (2015).Fuentes MMPB, Blackwood J, Jones B, Kim M, Leis B, Limpus CJ, Marsh H, Mitchell J, Pouzols FM, Pressey RL, Visconti P. A decision framework for prioritizing multiple management actions for threatened marine megafauna. Ecological Applications. 2015;25:200–214. doi: 10.1890/13-1524.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes et al. (2010).Fuentes M, Dawson J, Smithers S, Hamann M, Limpus C. Sedimentological characteristics of key sea turtle rookeries: potential implications under projected climate change. Marine and Freshwater Research. 2010;61:464–473. doi: 10.1071/MF09142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, Limpus & Hamann (2011).Fuentes M, Limpus C, Hamann M. Vulnerability of sea turtle nesting grounds to climate change. Global Change Biology. 2011;17:140–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02192.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes et al. (2009).Fuentes M, Maynard J, Guinea M, Bell I, Werdell P, Hamann M. Proxy indicators of sand temperature help project impacts of global warming on sea turtles in northern Australia. Endangered Species Research. 2009;9:33–40. doi: 10.3354/esr00224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki & Lamont (2016).Fujisaki I, Lamont MM. The effects of large beach debris on nesting sea turtles. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2016;482:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2016.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garmestani et al. (2000).Garmestani AS, Percival HF, Portier KM, Rice KG. Nest-site selection by the loggerheaf sea turtle in Florida’s Ten Thousand Islands. Journal of Herpetology. 2000;34:504–510. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, Limpus & Owens (2002).Hamann M, Limpus CJ, Owens DW. Reproductive cycles of males and females. In: Lutz PL, Musick JA, Wyneken J, editors. The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2002. pp. 135–162. [Google Scholar]

- Harris et al. (2015).Harris LR, Nel R, Oosthuizen H, Meÿer M, Kotze D, Anders D, McCue S, Bachoo S. Paper-efficient multi-species conservation and management are not always field-effective: the status and future of Western Indian Ocean leatherbacks. Biological Conservation. 2015;191:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison (1966).Harrison TP. The Phoenix and the Turtle: Shakespeare’s Poem and Chester’s Loues Martyr by William H. Matchett [review] Modern Philology. 1966;64(2):155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Hart et al. (2014).Hart CE, Ley-Quiñonez C, Maldonado-Gasca A, Zavalanorzagaray A, Aabreu-Grobois F. Nesting characteristics of olive Ridley turtles (Lepidochelys Olivacea) on El Naranjo Beach, Nayarit, Mexico. Herpetological Conservation and Biology. 2014;9:524–534. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes et al. (2009).Hawkes LA, Broderick AC, Godfrey MH, Godley BJ. Climate change and marine turtles. Endangered Species Research. 2009;7:137–154. doi: 10.3354/esr00198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hays et al. (1995).Hays G, Mackay A, Adams C, Mortimer J, Speakman J, Boerema M. Nest site selection by sea turtles. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 1995;75:667–674. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400039084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hays & Speakman (1993).Hays GC, Speakman JR. Nest placement by loggerhead turtles, Caretta caretta. Animal Behaviour. 1993;45:47–53. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1993.1006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks & Scott (1991).Horrocks J, Scott N. Nest site location and nest success in the Hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata in Barbados West-Indies. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1991;69:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Huijbers et al. (2015).Huijbers CM, Schlacher TA, Schoeman DS, Olds AD, Weston MA, Connolly RM. Limited functional redundancy in vertebrate scavenger guilds fails to compensate for the loss of raptors from urbanized sandy beaches. Diversity and Distributions. 2015;21:55–63. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt et al. (2005).Hunt Jr ER, Cavigelli M, Daughtry CT, McMurtrey III J, Walthall C. Evaluation of digital photography from model aircraft for remote sensing of crop biomass and nitrogen status. Precision Agriculture. 2005;6:359–378. doi: 10.1007/s11119-005-2324-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James & Robson (2014).James MR, Robson S. Mitigating systematic error in topographic models derived from UAV and ground based image networks. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 2014;39:1413–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers & Godley (2016).Jeffers VF, Godley BJ. Satellite tracking in sea turtles: how do we find our way to the conservation dividends? Biological Conservation. 2016;199:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones (2001).Jones J. Habitat selection studies in avian ecology: a critical review. The Auk. 2001;118:557–562. doi: 10.1642/0004-8038(2001)118[0557:HSSIAE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel & Mrosovsky (2004).Kamel SJ, Mrosovsky N. Nest site selection in leatherbacks, Dermochelys coriacea: individual patterns and their consequences. Animal Behaviour. 2004;68:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel & Mrosovsky (2005).Kamel SJ, Mrosovsky N. Repeatability of nesting preferences in the hawksbill sea turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, and their fitness consequences. Animal Behaviour. 2005;70:819–828. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel & Mrosovsky (2006).Kamel SJ, Mrosovsky N. Inter-seasonal maintenance of individual nest site preferences in hawksbill sea turtles. Ecology. 2006;87:2947–2952. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[2947:imoins]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamrowski et al. (2014).Kamrowski RL, Limpus C, Jones R, Anderson S, Hamann M. Temporal changes in artificial light exposure of marine turtle nesting areas. Global Change Biology. 2014;20:2437–2449. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamrowski et al. (2012).Kamrowski RL, Limpus C, Moloney J, Hamann M. Coastal light pollution and marine turtles: assessing the magnitude of the problem. Endangered Species Research. 2012;19:85–98. doi: 10.3354/esr00462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karavas et al. (2005).Karavas N, Georghiou K, Arianoutsou M, Dimopoulos D. Vegetation and sand characteristics influencing nesting activity of Caretta caretta on Sekania beach. Biological Conservation. 2005;121:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2004.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaska et al. (2010).Kaska Y, Başkale E, Urhan R, Katılmış Y, Gidiş M, Sarı F, Sözbilen D, Canbolat AF, Yılmaz F, Barlas M. Natural and anthropogenic factors affecting the nest-site selection of Loggerhead Turtles, Caretta caretta, on Dalaman-Sarıgerme beach in South-west Turkey: (Reptilia: Cheloniidae) Zoology in the Middle East. 2010;50:47–58. doi: 10.1080/09397140.2010.10638411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katselidis et al. (2013a).Katselidis KA, Schofield G, Stamou G, Dimopoulos P, Pantis JD. Evidence-based management to regulate the impact of tourism at a key marine turtle rookery on Zakynthos Island, Greece. Oryx. 2013a;47:584–594. [Google Scholar]

- Katselidis et al. (2013b).Katselidis KA, Schofield G, Stamou G, Dimopoulos P, Pantis JD. Employing sea-level rise scenarios to strategically select sea turtle nesting habitat important for long-term management at a temperate breeding area. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2013b;450:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kikukawa, Kamezaki & Ota (1999).Kikukawa A, Kamezaki N, Ota H. Factors affecting nesting beach selection by loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta): a multiple regression approach. Journal of Zoology. 1999;249:447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont & Houser (2014).Lamont MM, Houser C. Spatial distribution of loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) emergences along a highly dynamic beach in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2014;453:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Leon et al. (2015).Leon JX, Roelfsema CM, Saunders MI, Phinn SR. Measuring coral reef terrain roughness using ‘Structure-from-Motion’ close-range photogrammetry. Geomorphology. 2015;242:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Liles et al. (2015).Liles MJ, Peterson MJ, Seminoff JA, Altamirano E, Henríquez AV, Gaos AR, Gadea V, Urteaga J, Torres P, Wallace BP. One size does not fit all: importance of adjusting conservation practices for endangered hawksbill turtles to address local nesting habitat needs in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Biological Conservation. 2015;184:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.02.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limpus (2008).Limpus CJ. A biological review of Australian marine turtles: green turtle, Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus) Brisbane: Queensland Environmental Protection Agency; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Limpus & Fien (2008).Limpus CJ, Fien L. A biological review of Australian marine turtles 1. Loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus). The State of Queensland (Australia) Brisbane: Environmental Protection Agency; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Limpus & Kamrowski (2013).Limpus C, Kamrowski RL. Ocean-finding in marine turtles: the importance of low horizon elevation as an orientation cue. Behaviour. 2013;150:863–893. doi: 10.1163/1568539X-00003083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limpus & Limpus (2003).Limpus CJ, Limpus DJ. Loggerhead turtles in the equatorial and southern Pacific Ocean: a species in decline. In: Bolten AB, Witherington BE, editors. Loggerhead sea turtles. Smithsonian Books; Washington, D.C.: 2003. pp. 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini et al. (2013).Mancini F, Dubbini M, Gattelli M, Stecchi F, Fabbri S, Gabbianelli G. Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) for high-resolution reconstruction of topography: the structure from motion approach on coastal environments. Remote Sensing. 2013;5:6880–6898. doi: 10.3390/rs5126880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin & Roper (1988).Martin TE, Roper JJ. Nest predation and nest-site selection of a wastern population of the hermit thrush. The Condor. 1988;90:51–57. doi: 10.2307/1368432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaris, Matsinos & Margaritoulis (2006).Mazaris AD, Matsinos YG, Margaritoulis D. Nest site selection of loggerhead sea turtles: the case of the island of Zakynthos, W Greece. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2006;336:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Mazaris, Matsinos & Pantis (2009).Mazaris AD, Matsinos G, Pantis JD. Evaluating the impacts of coastal squeeze on sea turtle nesting. Ocean & Coastal Management. 2009;52:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2008.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor et al. (2013).Mazor T, Levin N, Possingham HP, Levy Y, Rocchini D, Richardson AJ, Kark S. Can satellite-based night lights be used for conservation? The case of nesting sea turtles in the Mediterranean. Biological Conservation. 2013;159:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Limpus & Godfrey (2003).Miller JD, Limpus CJ, Godfrey MH. Nest site selection, oviposition, eggs, development, hatching, and emergence of loggerhead turtles. In: Bolten AB, Witherington BE, editors. Loggerhead sea turtles. Smithsonian Institution Press; Washington, D.C.: 2003. pp. 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Warner & Janzen (2013).Mitchell TS, Warner DA, Janzen FJ. Phenotypic and fitness consequences of maternal nest-site choice across multiple early life stages. Ecology. 2013;94:336–345. doi: 10.1890/12-0343.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris (2011).Morris DW. Adaptation and habitat selection in the eco-evolutionary process. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2011;278:2401–2411. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosier (1998).Mosier AE. The impact of coastal armoring structures on sea turtle nesting behavior at three beaches on the east coast of Florida. University of South Florida; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mosier & Witherington (2002).Mosier AE, Witherington BE. Documented effects of coastal armoring structures on sea turtle nesting behavior. In: Proceedings of the twentieth annual symposium on sea turtle biology and conservation; Silver Spring: NOAA; 2002. pp. 204–306. [Google Scholar]

- Mousseau & Fox (1998).Mousseau TA, Fox CW. The adaptive significance of maternal effects. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1998;13:403–407. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nel, Punt & Hughes (2013).Nel R, Punt AE, Hughes GR. Are coastal protected areas always effective in achieving population recovery for nesting sea turtles? 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nilsson (1984).Nilsson SG. The evolution of nest-site selection amongst hole-hesting burds—the importance of nest predation and competition. Ornis Scandinavica. 1984;15:167–175. doi: 10.2307/3675958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PCC (2014).PCC . Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. In: Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL, editors. Part A global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 1132 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller, Limpus & Bjorndal (2009).Pfaller JB, Limpus CJ, Bjorndal KA. Nest-site selection in individual loggerhead turtles and consequences for doomed-egg relocation. Conservation Biology. 2009;23:72–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike (2013a).Pike DA. Climate influences the global distribution of sea turtle nesting. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2013a;22:555–566. doi: 10.1111/geb.12025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pike (2013b).Pike DA. Forecasting range expansion into ecological traps: climate-mediated shifts in sea turtle nesting beaches and human development. Global Change Biology. 2013b;19:3082–3092. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putman, Bane & Lohmann (2010a).Putman NF, Bane JM, Lohmann KJ. Sea turtle nesting distributions and oceanographic constraints on hatchling migration. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010a;277:3631–3637. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putman, Shay & Lohmann (2010b).Putman NF, Shay TJ, Lohmann KJ. Is the geographic distribution of nesting in the Kemp’s ridley turtle shaped by the migratory needs of offspring? Integrative and Comparative Biology. 2010b;50:305–314. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas et al. (2015).Rivas ML, Tomillo PS, Uribeondo JD, Marco A. Leatherback hatchling sea-finding in response to artificial lighting: interaction between wavelength and moonlight. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2015;463:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2014.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizkalla & Savage (2010).Rizkalla CE, Savage A. Impact of seawalls on loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) nesting and hatching success. Journal of Coastal Research. 2010;27:166–173. doi: 10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-10-00081.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roe, Clune & Paladino (2013).Roe JH, Clune PR, Paladino FV. Characteristics of a leatherback nesting beach and implications for coastal development. Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2013;12:34–43. doi: 10.2744/CCB-0967.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roe et al. (2014).Roe JH, Morreale SJ, Paladino FV, Shillinger GL, Benson SR, Eckert SA, Bailey H, Tomillo PS, Bograd SJ, Eguchi T, Dutton PH, Seminoff JA, Block BA, Spotila JR. Predicting bycatch hotspots for endangered leatherback turtles on longlines in the Pacific Ocean. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2014;281:20132559. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romstad & Etzelmüller (2012).Romstad B, Etzelmüller B. Mean-curvature watersheds: a simple method for segmentation of a digital elevation model into terrain units. Geomorphology. 2012;139:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon & Witherington (1995).Salmon M, Witherington BE. Artificial lighting and seafinding by loggerhead hatchlings: evidence for lunar modulation. Copeia. 1995;1995:931–938. [Google Scholar]

- Santos et al. (2015).Santos KC, Livesey M, Fish M, Lorences AC. Climate change implications for the nest site selection process and subsequent hatching success of a green turtle population. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 2015 Epub ahead of print July 08 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sappington, Longshore & Thompson (2007).Sappington JM, Longshore KM, Thompson DB. Quantifying landscape ruggedness for animal habitat analysis: a case study using bighorn sheep in the Mojave Desert. Journal of Wildlife Management. 2007;71:1419–1426. doi: 10.2193/2005-723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlacher et al. (2007).Schlacher TA, Dugan J, Schoeman DS, Lastra M, Jones A, Scapini F, McLachlan A, Defeo O. Sandy beaches at the brink. Diversity and Distributions. 2007;13:556–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00363.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlacher et al. (2016).Schlacher TA, Lucrezi S, Connolly RM, Peterson CH, Gilby BL, Maslo B, Olds AD, Walker SJ, Leon JX, Huijbers CM. Human threats to sandy beaches: a meta-analysis of ghost crabs illustrates global anthropogenic impacts. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2016;169:56–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2015.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlacher, Meager & Nielsen (2014).Schlacher TA, Meager JJ, Nielsen T. Habitat selection in birds feeding on ocean shores: landscape effects are important in the choice of foraging sites by oystercatchers. Marine Ecology. 2014;35:67–76. doi: 10.1111/maec.12055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlacher & Thompson (2012).Schlacher TA, Thompson L. Beach recreation impacts benthic invertebrates on ocean-exposed sandy shores. Biological Conservation. 2012;147:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlacher et al. (2015).Schlacher TA, Weston MA, Lynn D, Schoeman DS, Huijbers CM, Olds AD, Masters S, Connolly RM. Conservation gone to the dogs: when canids rule the beach in small coastal reserves. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2015;24:493–509. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0830-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeman, Schlacher & Defeo (2014).Schoeman DS, Schlacher TA, Defeo O. Climate-change impacts on sandy-beach biota: crossing a line in the sand. Global Change Biology. 2014;20:2383–2392. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, Lopez & Da Rocha (2009).Serafini TZ, Lopez GG, Da Rocha P. LB. Nest site selection and hatching success of hawksbill and loggerhead sea turtles (Testudines, Cheloniidae) at Arembepe Beach, northeastern Brazil. Phyllomedusa: Journal of Herpetology. 2009;8:03–17. doi: 10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v8i1p03-17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Short & Jackson (2013).Short A, Jackson D. Reference module in earth systems and environmental sciences: treatise on geomorpholoy. vol. 10. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2013. Beach morphodynamics; pp. 106–129. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier (2009).Spanier MJ. Beach erosion and nest site selection by the leatherback sea turtle Dermochelys coriacea (Testudines: Dermochelyidae) and implications for management practices at Playa Gandoca, Costa Rica. International Journal of Tropical Biology and Conservation. 2009;58 doi: 10.15517/rbt.v58i4.5408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneburner & Richardson (1981).Stoneburner D, Richardson J. Observations on the role of temperature in loggerhead turtle nest site selection. Copeia. 1981:238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Thums et al. (2016).Thums M, Whiting SD, Reisser J, Pendoley KL, Pattiaratchi CB, Proietti M, Hetzel Y, Fisher R, Meekan MG. Artificial light on water attracts turtle hatchlings during their near shore transit. Royal Society Open Science. 2016;3:160142. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkozan, Yamamoto & Yilmaz (2011).Turkozan O, Yamamoto K, Yilmaz C. Nest site preference and hatching success of green (Chelonia mydas) and loggerhead (Caretta caretta) sea turtles at Akyatan Beach, Turkey. Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2011;10:270–275. doi: 10.2744/CCB-0861.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber et al. (2014).Weber SB, Weber N, Ellick J, Avery A, Frauenstein R, Godley BJ, Sim J, Williams N, Broderick AC. Recovery of the South Atlantic’s largest green turtle nesting population. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2014;23:3005–3018. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0759-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weishampel et al. (2003).Weishampel JF, Bagley DA, Ehrhart LM, Rodenbeck BL. Spatiotemporal patterns of annual sea turtle nesting behaviors along an East Central Florida beach. Biological Conservation. 2003;110:295–303. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00232-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westoby et al. (2012).Westoby M, Brasington J, Glasser N, Hambrey M, Reynolds J. ‘Structure-from-Motion’photogrammetry: a low-cost, effective tool for geoscience applications. Geomorphology. 2012;179:300–314. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witherington (1992).Witherington BE. Behavioral responses of nesting sea turtles to artificial lighting. Herpetologica. 1992;48:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Witherington, Hirama & Mosier (2011).Witherington B, Hirama S, Mosier A. Sea turtle responses to barriers on their nesting beach. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2011;401:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Bjorndal & Ross (2000).Wood DW, Bjorndal KA, Ross S. Relation of temperature, moisture, salinity, and slope to nest site selection in loggerhead sea turtles. Copeia. 2000;2000:119–119. doi: 10.1643/0045-8511(2000)2000[0119:ROTMSA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen & Thorne (1987).Zevenbergen LW, Thorne CR. Quantitative analysis of land surface topography. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 1987;12:47–56. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Spatial distribution of nest sites for 2008–2009 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2009–2010 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2010–2011 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2011–2012 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2012–2013 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2013–2014 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Spatial distribution of nest sites for the 2015–2016 nesting season (Map data ©NearMap Pty. Ltd. 2015).

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as Data S1.