Abstract

BACKGROUND

The molecular determinants of clinical responses to decitabine therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are unclear.

METHODS

We enrolled 84 adult patients with AML or MDS in a single-institution trial of decitabine to identify somatic mutations and their relationships to clinical responses. Decitabine was administered at a dose of 20 mg per square meter of body-surface area per day for 10 consecutive days in monthly cycles. We performed enhanced exome or gene-panel sequencing in 67 of these patients and serial sequencing at multiple time points to evaluate patterns of mutation clearance in 54 patients. An extension cohort included 32 additional patients who received decitabine in different protocols.

RESULTS

Of the 116 patients, 53 (46%) had bone marrow blast clearance (<5% blasts). Response rates were higher among patients with an unfavorable-risk cytogenetic profile than among patients with an intermediate-risk or favorable-risk cytogenetic profile (29 of 43 patients [67%] vs. 24 of 71 patients [34%], P<0.001) and among patients with TP53 mutations than among patients with wild-type TP53 (21 of 21 [100%] vs. 32 of 78 [41%], P<0.001). Previous studies have consistently shown that patients with an unfavorable-risk cytogenetic profile and TP53 mutations who receive conventional chemotherapy have poor outcomes. However, in this study of 10-day courses of decitabine, neither of these risk factors was associated with a lower rate of overall survival than the rate of survival among study patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetic profiles.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with AML and MDS who had cytogenetic abnormalities associated with unfavorable risk, TP53 mutations, or both had favorable clinical responses and robust (but incomplete) mutation clearance after receiving serial 10-day courses of decitabine. Although these responses were not durable, they resulted in rates of overall survival that were similar to those among patients with AML who had an intermediate-risk cytogenetic profile and who also received serial 10-day courses of decitabine.

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are clonal disorders of myeloid hematopoiesis.1 Adult patients with AML who have karyotypes that are associated with unfavorable risk and older patients with AML (≥60 years of age) have poor outcomes, with a median survival of approximately 1 year.2,3 Patients with AML and TP53 mutations tend to be older (median age, 61 to 67 years), and almost all have karyotypes that are associated with unfavorable risk; if they receive standard cytotoxic chemotherapy, these patients have especially poor outcomes (median survival, 4 to 6 months).3-6

Decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) is commonly used as a single agent to treat patients with MDS and elderly patients with AML.7 However, response rates are low. Combined rates of complete remission (complete remission with recovery of peripheral-blood counts) and complete remission with incomplete count recovery typically range from 20 to 35%.8 Studies with longer exposure times to decitabine (administered on days 1 through 10 of 28-day cycles instead of on days 1 through 5) show an improved response rate (range, 40 to 64%).9,10

Several studies have sought to identify bio-markers (e.g., DNA methylation changes10-13 and mutations in DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, and TET2,14-16 along with miR-29b expression10) that might predict responses to decitabine. However, controversy still exists concerning the predictive value of these biomarkers, and none are currently used to guide decitabine therapy for individual patients.

In this trial, we used enhanced exome sequencing17 and gene-panel sequencing to determine whether the presence of specific mutations might correlate with a response or with resistance to decitabine and to characterize patterns of mutation clearance. Surprisingly, we found that clinical responses were highly correlated with the presence of TP53 mutations in the founding clone at presentation and that the rate of overall survival with 10-day courses of decita bine was similar among patients with cytogenetic abnormalities associated with unfavorable risk and among those with an intermediate-risk cytogenetic profile. Finally, serial exome sequencing revealed consistent mutation clearance in all evaluated patients with AML or MDS who had TP53 mutations. However, mutation clearance was never complete in patients who had a response to decitabine, even in those with complete clinical remission.

METHODS

TRIAL DESIGN AND OVERSIGHT

In this prospective, uncontrolled trial, 84 patients received decitabine at a dose of 20 mg per square meter of body-surface area per day on days 1 through 10 of 28-day cycles at Washington University in St. Louis between March 2013 and November 2015. The protocol is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

The trial was approved by the institutional review board at Washington University in St. Louis and was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. All the patients who were enrolled at Washington University in St. Louis provided written informed consent that explicitly included genome sequencing and data sharing with qualified investigators. Additional patients who were included in the extension cohort were enrolled in a study at the University of Chicago under an institutional review board–approved protocol that allowed for gene-panel sequencing and data sharing with qualified investigators. All the authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and vouch for the adherence to the study protocol and for the accuracy and completeness of the data reported.

The trial was designed and the manuscript was written by the first and last authors. The investigators performed the data analysis. No commercial entities were involved in the support, design, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

OBJECTIVES

The primary objective of the trial was to correlate clinical responses with mutation status. Secondary objectives were to correlate responses with the rate of mutation clearance, steady-state plasma decitabine levels, and methylation changes on day 10 of cycle 1.

ELIGIBILITY

Three groups of patients were enrolled: those with AML (excluding patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia) who were 60 years of age or older, those with relapsed AML, and those with trans-fusion-dependent MDS (Table 1). All the patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance-status score of 2 or less (on a 5-point scale, with higher numbers indicating increasing disability; lower numbers indicate greater functional independence, and a score of 3 indicates confinement to a bed or chair for >50% of waking hours), and preserved end-organ function (see the Methods section of the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). Eligibility requirements were intentionally broad and designed to reflect typical patterns of deci tabine use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline and Response to Decitabine.*

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 116) | TP53 Mutations (N = 21) | Wild-Type TP53 (N = 78) | TP53 Not Evaluated (N = 17) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing performed — no. (%) | |||||

| Any type | 99 (85) | 21 (100) | 78 (100) | 0 | |

| Exome | 39 (34) | 7 (33) | 32 (41) | 0 | |

| 264-gene panel | 15 (13) | 7 (33) | 8 (10) | 0 | |

| 8-gene panel | 45 (39) | 7 (33) | 38 (49) | 0 | |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 68 (59) | 9 (43) | 47 (60) | 12 (71) | 0.21 |

| Age at diagnosis — yr | 0.90 | ||||

| Median | 74 | 71 | 72 | 76 | |

| Range | 29–88 | 47–86 | 29–88 | 50–85 | |

| Disease — no. (%) | |||||

| AML | 54 (47) | 9 (43) | 34 (44) | 11 (65) | 1.00 |

| Relapsed AML | 36 (31) | 3 (14) | 31 (40) | 2 (12) | 0.04 |

| MDS | 26 (22) | 9 (43) | 13 (17) | 4 (24) | 0.02 |

| IPSS in patients with MDS — no./total no. (%)‡ | |||||

| Low | 1/26 (4) | 0 | 0 | 1/4 (25) | |

| Intermediate 1 | 8/26 (31) | 1/9 (11) | 4/13 (31) | 3/4 (75) | 0.40 |

| Intermediate 2 | 8/26 (31) | 1/9 (11) | 7/13 (54) | 0 | 0.08 |

| High | 9/26 (35) | 7/9 (78) | 2/13 (15) | 0 | 0.007 |

| Cytogenetic risk group — no. (%) | |||||

| Favorable | 5 (4) | 0 | 4 (5) | 1 (6) | 0.58 |

| Intermediate | 66 (57) | 1 (5) | 54 (69) | 11 (65) | <0.001 |

| Unfavorable | 43 (37) | 20 (95) | 19 (24) | 4 (24) | <0.001 |

| Not performed | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (6) | |

| Response — no. (%) | |||||

| Bone marrow blast clearance <5% blasts | 53 (46) | 21 (100) | 32 (41) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Complete remission | |||||

| With recovery of peripheral-blood counts | 15 (13) | 4 (19) | 11 (14) | 0 | 0.73 |

| With incomplete count recovery | 24 (21) | 9 (43) | 15 (19) | 0 | 0.04 |

| Morphologic complete remission | |||||

| With hematologic improvement | 6 (5) | 5 (24) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0.002 |

| Without hematologic improvement | 8 (7) | 3 (14) | 5 (6) | 0 | 0.36 |

| No bone marrow blast clearance | 63 (54) | 0 | 46 (59) | 5 (29) | <0.001 |

| Partial response | 9 (8) | 0 | 9 (12) | 0 | 0.05 |

| Stable disease | 23 (20) | 0 | 18 (23) | 5 (29) | 0.006 |

| Progressive disease | 19 (16) | 0 | 19 (24) | 0 | 0.003 |

| Samples not available for evaluation | 12 (10) | 0 | 0 | 12 (71) |

AML denotes acute myeloid leukemia, and MDS myelodysplastic syndromes.

P values are for the comparison of data from patients with TP53 mutations with data from patients with wild-type TP53.

Scores in the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) range from 0 to 3.5, with higher scores indicating a worse prognosis. A score of 0 indicates low risk, 0.5 to 1.0 (intermediate 1) and 1.5 to 2.0 (intermediate 2) intermediate risk, and 2.5 to 3.5 high risk. Scores are calculated according to the presence of bone marrow blasts, cytogenetic risk, and cytopenias.

RESPONSE CRITERIA AND END POINTS

Bone marrow samples were obtained on day 0, on day 10 of cycle 1, on day 28 of cycle 1, and on day 28 of even-numbered cycles. Deviation of up to 1 day for sample collection on day 10 and up to 2 days for sample collection on day 28 was permitted for patient convenience. Responses were reported on an intention-to-treat basis and were categorized according to the criteria of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. These categories were complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, morphologic complete remission, partial response, stable disease, and progressive disease.18,19 Patients from whom a bone marrow sample was not obtained on or after day 28 of cycle 1 were not evaluated. Bone marrow blast counts were reviewed centrally.

Patients with samples that were characterized in sequencing and methylation array studies were selected on the basis of clinical responses (i.e., a response that could be evaluated after two cycles or evidence of progressive disease after one cycle) and sufficient amounts of high-quality DNA. Karyotypes that are associated with unfavorable risk were defined as the presence of three or more abnormalities, deletions involving chromosomes 5, 7, or 17, or abnormalities in chromo-some 11 involving MLL. In patients with MDS, an isolated chromosome 5q deletion was not considered to be associated with unfavorable risk.

EXTENSION COHORT

An extension cohort included 32 additional patients. Of these patients, 24 had relapsed AML and received decitabine at a dose of 20 mg per square meter per day on days 1 through 10 in 28-day cycles between April 2005 and March 2010 at the University of Chicago.

The other eight patients all had AML, were 60 years of age or older, and received decitabine at a dose of 20 mg per square meter per day on days 1 through 5 in 28-day cycles at Washington University in St. Louis between January 2009 and June 2014. Five patients received decitabine as a single agent and three patients received decitabine in combination with panobinostat (a histone deacetylase inhibitor) at a dose of 10 mg per day three times a week.

MOLECULAR ANALYSES

Libraries for enhanced exome sequencing were enriched with the use of the NimbleGen exome reagent, version 3, with the addition of biotinylated probes targeting 264 genes that are recurrently mutated in patients with AML,17,20 and the libraries were sequenced with the use of the Illumina HiSeq 2000 or 2500 platforms. Amplicon-based panel testing that was designed to detect all common mutations within 8 genes (TP53, DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, ASXL1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and SF3B1) was performed with the use of the Ion AmpliSeq platform (see Table S1 and the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix). Exome sequencing data are being deposited in the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes under the accession number phs000159. DNA methylation arrays were performed and analyzed as described previously.20 Methylation array data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE80762.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed with the use of Excel (Microsoft), GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software), and SAS, version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute). A detailed description of the statistical methods is provided in the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix.

RESULTS

PATIENTS

We enrolled 84 patients with AML or MDS in a prospective clinical trial of single-agent decitabine at Washington University in St. Louis (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). Patients received a median of two cycles of decitabine, and 59 patients received at least two cycles. The median follow-up of the 19 patients who remained alive was 19 months.

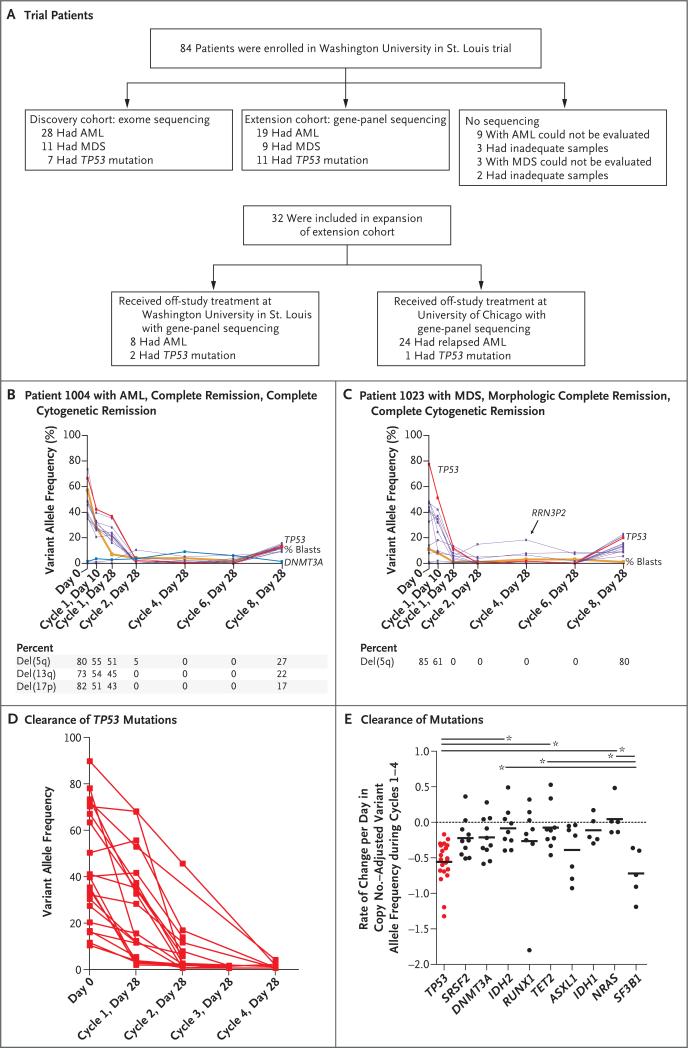

Figure 1. Clinical Responses in Patients with TP53 Mutations.

Panel A shows patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) in the discovery and extension cohorts. Samples obtained from 67 patients were evaluated in the study with sequence analysis at Washington University in St. Louis, and 32 additional patients, who received treatment at the University of Chicago or on alternative protocols at Washington University in St. Louis, were also included in the extension analysis. Panels B and C show mutation clearance observed in 2 patients with TP53 mutations. The variant allele frequency is the percentage of total reads that support a specific somatic mutation. The variant allele frequency of each identified mutation is indicated across time points. Variants in TP53 are indicated in red, variants in DNMT3A are indicated in blue, mutations in genes that are not recurrently mutated in AML20 are indicated in purple, and blast counts are indicated in orange. Relapse occurred in the patients shown in Panels B and C at day 28 of cycle 8. In Panel C, patient 1023 also had hematologic improvement in platelet and neutrophil counts but incomplete recovery of red cells. Panel D shows the rate of clearance of 21 TP53 mutations identified in 16 patients. Panel E shows the rate of clearance of mutations (specifically, in genes that were mutated in at least 5 of the 54 patients with samples that could be evaluated), with a median of four time points evaluated in each patient. One-way analysis of variance and the Tukey multiple-comparison test were performed to compare the means of mutation clearance for each gene. Horizontal bars with an asterisk denote P<0.05 for the indicated comparisons. Short horizontal bars within the data points denote the mean mutation clearance rate for the indicated gene.

An additional 32 patients who had received a similar regimen outside the aegis of our trial made up an independent extension set. These patients received the same 10-day decitabine regimen at the University of Chicago or decitabine in a 5-day regimen at Washington University in St. Louis.

TOXIC EFFECTS

As expected, adverse events were predominantly associated with neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).9,10,21 During cycles 1 and 2, we observed a total of 128 events of grade 3 through 5. Of these events, 93 (in 56 patients) were febrile neutropenia or other infectious events, and 9 (in 8 patients) were bleeding complications or trans-fusion reactions. Eight treatment-related deaths were due to infection (in 6 patients), acute kidney injury (in 1 patient), or cardiac arrest (in 1 patient).

RESPONSE

A total of 15 of the 116 patients in the combined patient cohorts (13%) had a complete remission, and an additional 38 patients had bone marrow blast clearance with less than 5% blasts (complete remission with incomplete count recovery or morphologic complete remission), for an overall response rate of 46%. A partial response was observed in 9 patients (8%), stable disease in 23 patients (20%), and progressive disease in 19 patients (16%) (Table 1).

Twelve patients withdrew from the protocol before a bone marrow biopsy could be performed at the end of cycle 1 and therefore could not be clinically evaluated for a response. Of these patients, 6 transitioned to hospice, 2 transitioned to cytotoxic chemotherapy, 2 had progressive disease, 1 had a myocardial infarction after one dose, and acute renal failure developed after one dose in 1 who had undergone orthotopic kidney transplantation. Responses correlated with the median number of cycles and performance status, but not with age or white-cell counts (Fig. S1A through S1E in the Supplementary Appendix).10

MUTATION CLEARANCE

The first 39 patients with samples that were sufficient for analysis constituted the discovery cohort. Samples were serially evaluated with enhanced exome sequencing (median, four separate time points per patient, 157 exomes in total) (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). In patients with AML and patients with MDS, the clearance of leukemia-specific mutations correlated closely with morphologic and cytogenetic responses (Fig. 1B and 1C).

We used gene-panel sequencing to evaluate sequential samples obtained from 15 additional patients at multiple time points. In total, 54 patients had samples that underwent serial evaluation. Mutations in only two genes (TP53 and SF3B1) had consistent, rapid reductions in variant allele frequency to levels of less than 5% (Fig. 1D and 1E). Bone marrow blast clearance frequently preceded mutation reduction (in 15 of 54 patients) (Fig. 1B, and Fig. S3B and S3C in the Supplementary Appendix), and mutation clearance was never complete.

We examined samples obtained from 20 patients with bone marrow blast clearance (those with complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, or morphologic complete remission) after day 28 of cycle 2. In these patients, we were able to detect leukemia-specific mutations during morphologic remission. This indicated that decitabine leads only to incomplete clearance of disease (average founding clone variant allele frequency at maximum clearance, 0.06% to 18.43%) (Fig. S1F in the Supplementary Appendix). We observed no difference in the extent of leukemia-specific mutation clearance between patients who had peripheral-blood count recovery (complete remission) and those who did not (complete remission with incomplete count recovery or morphologic complete remission), and the duration of remissions was similar in both groups (Fig. S1G and S1H in the Supplementary Appendix).

Differential sensitivity to decitabine was observed within subclones in 11 patients with samples that were evaluated by means of exome sequencing. Patterns that were observed included sensitive subclones within the background of a largely resistant founding clone in 2 patients (Fig. S3A in the Supplementary Appendix) and subclones with primary resistance to decitabine in 9 patients (Fig. S3B in the Supplementary Appendix). In the 9 patients who were evaluated at relapse, progression was associated with the outgrowth of one or more subclones, some of which were detectable before therapy (Fig. 1B and 1C, and Fig. S3B in the Supplementary Appendix).

Nonleukemic “rising clones” were also observed in 7 of the 22 patients who had a response (Fig. 1B and 1C, and Fig. S3C and S3D in the Supplementary Appendix), as described in patients with AML who have received induction therapy with daunorubicin and cytarabine.22 In 2 patients, the rising clones contained mutations in genes (DNMT3A and PPM1D) that had been previously identified in patients with age-related clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential23-26; data on the other genes in clonal hematopoiesis (RUNX1, UNC5C, RRN3P2, and SCAMP5) are lacking. We did not observe a correlation between the presence of clonal hematopoiesis in remission and incomplete hematopoietic count recovery (P=0.36 for the comparison between patients who had complete remission and incomplete count recovery or morphologic complete remission and patients who had complete remission).

Patients with stable disease and partial responses typically had stable or slowly decreasing mutation burdens, as expected (Figs. S4 and S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). However, all three cases of rapidly progressive disease were associated with stable mutation burdens (Fig. S6 in the Supplementary Appendix).

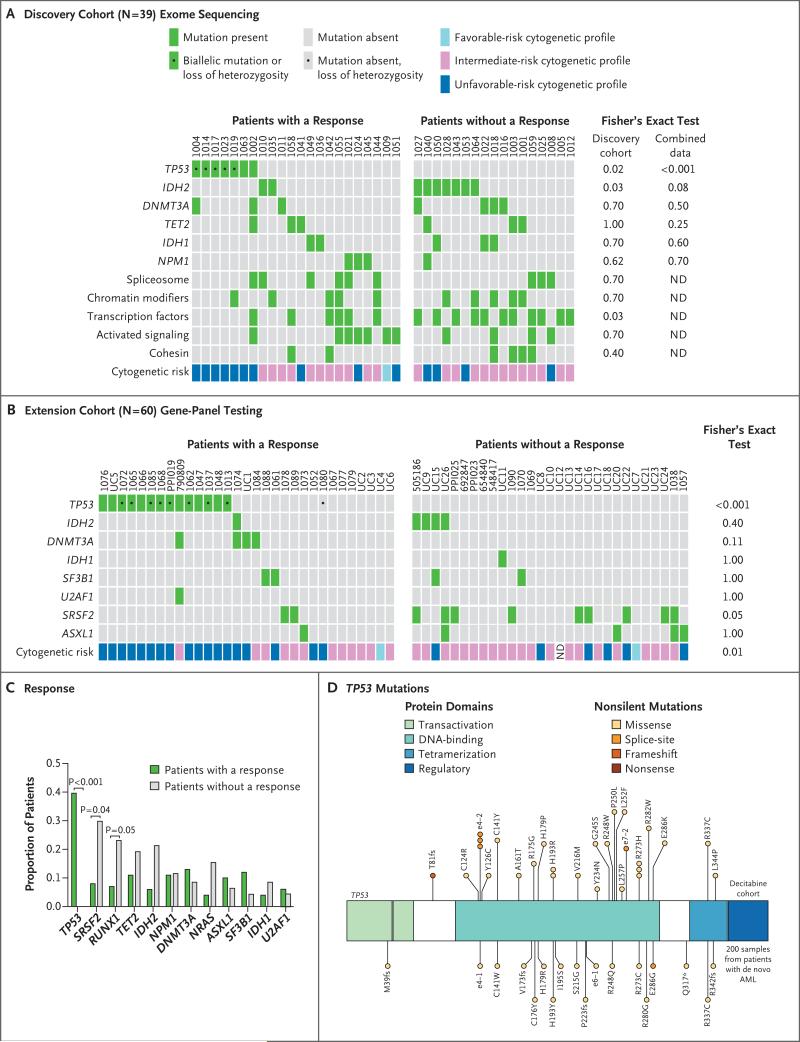

CORRELATION BETWEEN RESPONSES AND MUTATIONS AND CYTOGENETIC PROFILES

Among the first 39 patients, who constituted the discovery cohort, we observed blast clearance from the bone marrow (<5% residual blasts) in 22 patients (with complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, or morphologic complete remission). Surprisingly, all 7 patients with TP53 mutations had a response with bone marrow blast clearance, as compared with 15 of 32 patients without TP53 mutations (47%) (P=0.02) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Correlation between Somatic Mutations and Clinical Responses.

Panel A shows the results of enhanced exome sequencing in the discovery cohort among patients who had a response (complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, or morphologic complete remission) or no response (partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease). Panel B shows the results of gene-panel sequencing (264 genes in 15 patients and 8 genes in 45 patients) in patients in the extension cohort. ND denotes not done. Panel C shows the proportions of patients among all those in whom samples were sequenced (99 patients) who had a response or did not have a response, according to the presence of the indicated mutations. Panel D shows the locations and predicted consequences of TP53 mutations identified in this trial and in patients with AML in the Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network cohort.20

We therefore used gene-panel sequencing to evaluate samples obtained from 60 additional patients (51 with AML and 9 with MDS): 28 patients who were enrolled in this trial, 8 patients who received decitabine delivered in 5-day cycles at Washington University in St. Louis, and 24 patients who received decitabine with 10-day cycles at the University of Chicago (Figs. 1A and 2B). We observed TP53 mutations in 14 of 60 patients: 14 of 14 had blast clearance (complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, or morphologic complete remission) with decitabine therapy, and 17 of 46 patients with wild-type TP53 had blast clearance (P<0.001). One additional patient (Patient 1080) had evidence of TP53 loss of heterozygosity by single-nucleotide-polymorphism analysis in the gene-panel test and add(17)(p13) by cytogenetic profile, but a somatic mutation in TP53 coding sequences was not detected.

Of the samples obtained for sequencing from 53 patients who had a response (complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, or morphologic complete remission), 21 had TP53 mutations (40%) (P<0.001) (Fig. 2C, and Fig. S7 in the Supplementary Appendix). The spectrum of TP53 mutations that was detected in this cohort was very similar to that of mutations reported in other studies of AML, including the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network study of AML20 (Fig. 2D, and Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

CORRELATION BETWEEN RESPONSES AND BIOMARKERS

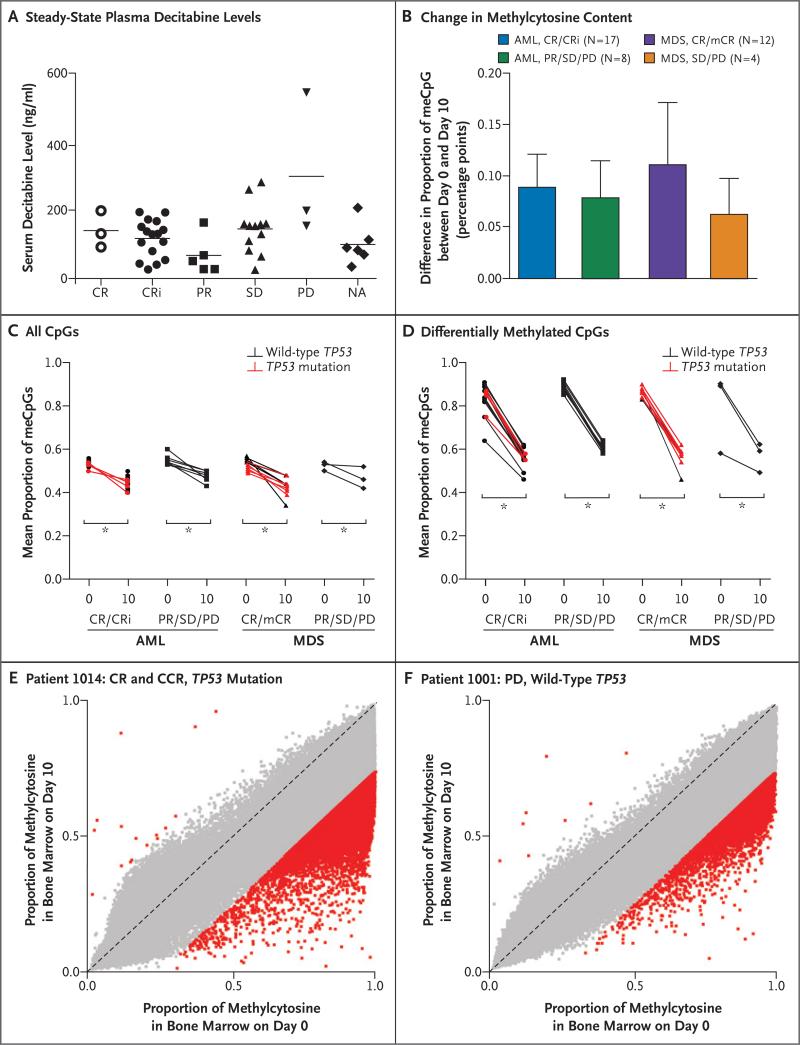

We correlated two pharmacologic markers with clinical responses to determine whether insufficient administration of decitabine or a failure of decitabine to cause DNA hypomethylation for other reasons was associated with a poor response. We observed no correlation between steady-state plasma decitabine levels on day 4 of the first cycle and responses (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Correlation between Clinical Responses and Pharmacologic and DNA Methylation Measurements.

Panel A shows steady-state plasma decitabine levels that were determined during day 4 of cycle 1 (deviation of up to 1 day for sample collection was permitted for patient convenience) (P=0.09 by analysis of variance for the comparison among all response groups). CR denotes complete remission, CRi complete remission with incomplete count recovery, mCR morphologic complete remission, meCpG methylated CpG, NA not applicable, PD progressive disease, PR partial response, and SD stable disease. The horizontal lines indicate pairwise comparisons with statistical differences. Panel B shows the absolute difference between the proportions of meCpGs on day 0 and day 10 of cycle 1, as determined with the use of Illumina Human Methylation 450 Bead Chip profiling (P=0.19 by analysis of variance for the comparison among all response groups). The I bars indicate standard deviation. Panel C shows the mean fraction of meCpGs per sample on day 0 and day 10, according to data shown in Panel B. Panel D shows the differences in the mean fraction of differentially methylated CpGs (those with a change in methylation of ≥25%) between day 0 and day 10. In Panels C and D, the asterisks indicate P<0.001 for the indicated comparisons. Panels E and F show examples of CpG methylation values across approximately 450,000 unique CpGs in representative patients. Samples from total bone marrow cells on day 0 and on day 10 of cycle 1 are compared. Red squares indicate CpGs with a difference of 25% or more in the proportion of cells with methylation at the indicated CpG, and gray squares indicate CpGs with a difference of less than 25%. Hypomethylation predominantly occurs at highly methylated CpGs, and hypomethylation is incomplete within the total bone marrow population. P values were calculated with the use of one-way analysis of variance and the Tukey multiple-comparison test. Similar results were obtained with the use of analysis of covariance (see the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix).

Bone marrow samples that were obtained on day 0 and on day 10 of cycle 1 were evaluated for CpG methylation values at approximately 450,000 genomic positions with the use of the Illumina Human Methylation 450 Bead Chip. In patients with AML and those with MDS, the reduction in methylcytosine content from day 0 to day 10 of cycle 1 was similar in patients who had a response (complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, or morphologic complete remission) and those who did not have a response (partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease). This reduction was also similar in patients who had TP53 mutations and those who did not have TP53 mutations and did not correlate with morphologic responses (Fig. 3B through 3D).

We observed very little change in subclonal architecture between day 0 and day 10 of cycle 1 in all patients (Fig. 1B and 1C, and Figs. S3 through S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). This finding suggests that the observed methylation changes were not the result of rapid shifts in the subclonal composition of samples with therapy.

CORRELATION BETWEEN BIOMARKERS AND SURVIVAL

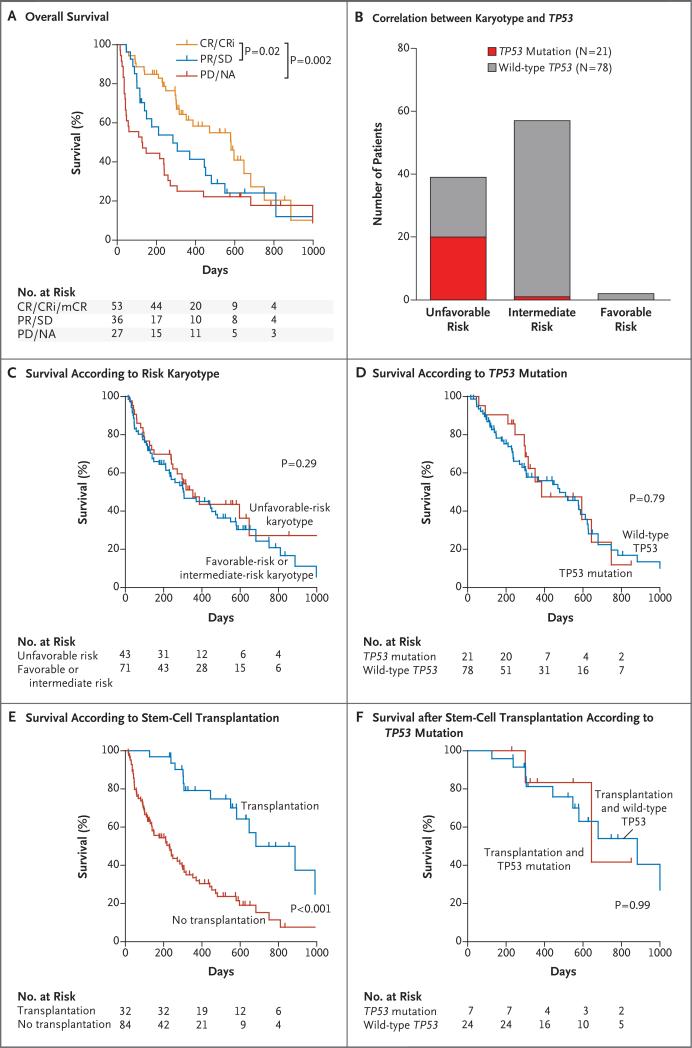

The analysis of survival outcomes was not a primary objective of this clinical trial owing to the lack of a comparator group and the anticipated heterogeneity of the patients enrolled. However, because the rate of overall survival correlated with clinical response, disease, age, and performance status, as expected10,21 (Fig. 4A, and Fig. S8 in the Supplementary Appendix), we performed a post hoc correlation between TP53 mutation status and cytogenetic risk.

Figure 4. Correlation between Clinical Variables and Survival.

Panel A shows the rate of overall survival among 116 patients as a function of responses to decitabine. CR/CRi/mCR denotes complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, or morphologic complete remission; PR/SD partial response or stable disease; and PD/NA progressive disease or not assessed. Panel B shows the correlation between karyotype and the presence of TP53 mutations. Panel C shows the rate of survival among 114 patients with karyotypes associated with unfavorable risk or with karyotypes associated with either intermediate risk or favorable risk. (Karyotype data were not available for 2 patients.) Panel D shows the rate of survival among patients with TP53 mutations and patients with wild-type TP53. Panel E shows the rate of survival among 116 patients according to whether they had undergone allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Half the patients received a conditioning regimen of fludarabine and busulfan, a third received fludarabine and melphalan, and the others received busulfan and cyclophosphamide, cladribine and melphalan, or fludarabine and total-body irradiation. No differences in survival were noted on the basis of the conditioning regimen. Panel F shows the rate of survival among patients who underwent allogeneic stem-cell transplantation according to the type of TP53 mutation. P values were calculated with the use of pair-wise Wilcoxon analysis (Panels A and F) and log-rank analysis (Panels C through E).

TP53 mutations were observed almost exclusively in patients with unfavorable-risk cytogenetic profiles, as expected, in 20 of 21 patients (Fig. 4B); 1 patient had normal cytogenetic findings, but only five metaphases were evaluated. Surprisingly, overall survival was not negatively affected by cytogenetic abnormalities associated with unfavorable risk (Fig. 4C) (median survival, 11.6 months among patients with unfavorable risk and 10 months among patients with favorable or intermediate risk, P=0.29) or the presence of TP53 mutations (Fig. 4D) (median survival, 12.7 months among patients with TP53 mutations and 15.4 months among patients with wild-type TP53, P=0.79). TP53 mutations were associated with a trend toward decreased survival among patients with MDS, but not among patients with AML (P=0.08) (Fig. S9A through S9D in the Supplementary Appendix).

Of all the factors analyzed, treatment consolidation with allogeneic stem-cell transplantation had the greatest effect on overall survival (Cox proportional-hazards model with stepwise regression for transplantation vs. no transplantation, P<0.001) (Fig. 4E, and Fig. S8 in the Supplementary Appendix). However, transplantation and survival outcomes were not adversely affected by TP53 status (Fig. 4F, and Fig. S8F in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This trial was designed to identify molecular markers associated with a response or with resistance to single-agent decitabine in patients with AML or MDS. Clinical responses correlated strongly with the presence of karyotypes associated with unfavorable risk and the presence of TP53 mutations. We observed bone marrow blast clearance (complete remission, complete remission with incomplete count recovery, or morphologic complete remission) in 29 of 43 patients with karyotypes associated with unfavorable risk (67%) versus 24 of 71 patients with karyotypes associated with intermediate or favorable risk (34%) and in 21 of 21 patients with TP53 mutations (100%) versus 32 of 78 patients with wild-type TP53 (41%) (P<0.001 for both comparisons) (Fig. 2). A total of 20 of 21 patients with TP53 mutations had a karyotype associated with unfavorable risk. Other investigators have also found that response rates among patients who have AML or MDS with karyotypes associated with unfavorable risk and who receive decitabine or azacitidine are at least equivalent to, if not slightly higher than, those among patients with an intermediate-risk cytogenetic profile.9,10,27-29

These outcomes contrast sharply with those in patients with AML who receive standard anthracycline-based and cytarabine-based induction chemotherapy, in whom the presence of TP53 mutations is associated with a dismal prognosis, with initial response rates of only 20 to 30%.3,30 Furthermore, median survival among these patients tends to be 4 to 6 months, with overall survival of only approximately 10 months after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation4,30,31; this contrasts with the 12.7-month median survival in the cohort of patients who received decitabine. These data suggest that the poor prognosis associated with an unfavorable-risk cytogenetic profile, the presence of TP53 mutations, or both may be specific for the treatment approach and may be mitigated with decitabine therapy.

Two previously recognized clinical features of decitabine responses have been clarified by this analysis. First, responses tend to be slow: most patients require at least two monthly cycles to achieve maximum clinical responses, and many patients who have a response require three or more cycles.9,21 We observed that bone marrow blast clearance usually precedes mutation clearance; this indicates that decitabine may induce differentiation before elimination of leukemic cells, as has been suggested previously.32 This process, like other differentiation responses, appears to require months of therapy. Second, responses are short-lived: remissions usually last less than a year, especially after discontinuation of therapy.33 Decitabine did not clear all leukemia-specific mutations in any patient tested (Fig. 1, and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Thus, the short durations of remission are due to incomplete clearance of leukemia cells bearing the pathogenetically relevant driver mutations.

The mechanisms responsible for primary decitabine resistance are not yet clear. Resistance does not appear to be due to inadequate dosing or metabolism of the drug; neither the levels of steady-state plasma decitabine nor the extent of reduction of cytosine methylation in bone marrow cells immediately after treatment corresponded with clinical responses (Fig. 3). Therefore, decitabine appears to hit the methylation target in most patients, regardless of their clinical responses. Furthermore, we carefully evaluated the methylcytosine array data from these patients (and from those in the TCGA study of de novo AML20) to identify a canonical methylation signature driven by TP53 mutations. Such a signature would suggest that patients with TP53 mutations may be epigenetically primed to have a response to decitabine, but no such signature could be identified. The mechanisms underlying the sensitivity of patients with AML or MDS and TP53 mutations to decitabine are therefore unclear at present but will be important to define in other studies.

Subclones within individual AML samples have variable sensitivities to decitabine; this suggests that subclones may contain genetic or epigenetic modifiers that influence their sensitivity to the drug. We observed both sensitive subclones (Fig. S3A in the Supplementary Appendix) and resistant subclones (Fig. S3B in the Supplementary Appendix); all relapses were associated with the expansion of one or more subclones (Fig. 1). No genetic rules could be established to predict subclonal sensitivity in this trial, although recurrent patterns may be identified in larger cohorts.

Although the presence of TP53 mutations appears to be associated with a high degree of decitabine sensitivity, relapses in these patients were also associated with the outgrowth of a preexisting subclone in all cases (Fig. 1B and 1C). Thus, patients with TP53 mutations may not be invariably sensitive to decitabine, and resistant populations of cells commonly emerge during therapy. Furthermore, patients who have AML with TP53 mutations only in subclones (i.e., not in the founding clone) would not be expected to have complete clinical responses, since only a fraction of the tumor cells would be potentially susceptible to decitabine. Regardless, the differential susceptibility of subclones to decitabine in individual patients strongly suggests that the mechanisms of response are directly influenced by cell-intrinsic factors. However, it is also possible that decitabine could induce clinical responses in some patients through non–cell-intrinsic mechanisms. This drug can activate the expression of endogenous retroviruses and alter regulatory T-cell maturation.34-36 Either of these mechanisms could potentially alter the immune surveillance of AML or MDS cells and lead to clinical responses.

Finally, the rate of survival among patients with AML who have unfavorable-risk cytogenetic profiles, TP53 mutations, or both, and who receive decitabine is similar to that among patients with an intermediate-risk cytogenetic profile who receive decitabine. Additional studies will be required to determine whether these differences in survival are truly due to improved responses associated with decitabine or whether conventional chemotherapy with an anthracycline and cytarabine actually decreases the rate of survival among patients with unfavorable-risk cytogenetic profiles.

In conclusion, these data show that different groups of patients with AML or MDS are likely to have a different response to different types of chemotherapy. Although patients with AML or MDS who have TP53 mutations have very low response rates after standard cytotoxic therapy, all patients with a TP53 mutation had a response to 10-day courses of decitabine in this trial. TP53 mutations form the nexus of the worst prognostic group in AML and MDS. These data suggest an alternative up-front strategy for the treatment of this group of ultra-high-risk patients that will need to be verified in prospective trials. Decitabine as a single agent is not a cure for anyone with these diseases: the rapid selection of resistant subclones by decitabine and the incomplete clearance of leukemia-specific mutations (even in patients who have a response) explain why remissions are generally short-lived. However, the use of decitabine may be an important way to induce clinical remissions in patients with AML who have TP53 mutations and who have disease that is notoriously resistant to induction therapy with standard cytotoxic chemotherapy. Such therapy may also provide a bridge to allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for some patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Specialized Program of Research Excellence in AML of the National Cancer Institute (P50 CA171963, to Dr. Link) and the Genomics of AML Program Project (P01 CA101937, to Dr. Ley). Three patients received treatment in the LBH589 Plus Decitabine for Myelodysplastic Syndromes or Acute Myeloid Leukemia trial, which was supported by Novartis.

Dr. Uy reports receiving fees for serving on an advisory board and clinical-trial support from Novartis; Dr. Jacoby, receiving consulting fees and fees for end-point adjudication from Quintiles and clinical-trial support from Sunesis Pharmaceuticals; and Dr. Graubert, receiving consulting fees from Agios.

We thank Paige Schnoebelen, Theresa Fletcher, Megan Haney, and Shannon Kramer for assistance in patient enrollment, sample collection, and clinical data processing; Hideji Fujiwara, Ph.D., and Daniel Ory, M.D., at the Washington University in St. Louis Mass Spectrometry Core for analyzing plasma decitabine levels; Greg Malnassy, Nichole Helton, and the Washington University in St. Louis Tissue Procurement Core for sample storage and preparation; the Genome Technology Access Center at Washington University in St. Louis for support in processing and analyzing the HumanMethylation450 BeadChips; and David H. Spencer, M.D., Ph.D., for assistance with the evaluation of methylation data from the AML cohort in the Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network study.

Footnotes

(Funded by the National Cancer Institute and others; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01687400.)

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Lindsley RC, Mar BG, Mazzola E, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations. Blood. 2015;125:1367–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-610543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klepin HD. Myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:155–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rücker FG, Schlenk RF, Bullinger L, et al. TP53 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype correlate with specific copy number alterations, monosomal karyotype, and dismal outcome. Blood. 2012;119:2114–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-375758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohgami RS, Ma L, Merker JD, et al. Next-generation sequencing of acute myeloid leukemia identifies the significance of TP53, U2AF1, ASXL1, and TET2 mutations. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:706–14. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sallman DA, Komrokji R, Vaupel C, et al. Impact of TP53 mutation variant allele frequency on phenotype and outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2016;30:666–73. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hou HA, Chou WC, Kuo YY, et al. TP53 mutations in de novo acute myeloid leukemia patients: longitudinal follow-ups show the mutation is stable during disease evolution. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e331. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik P, Cashen AF. Decitabine in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in elderly patients. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:53–61. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S40600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim TK, Gore SD, Zeidan AM. Epi-genetic therapy in acute myeloid leukemia: current and future directions. Semin Hematol. 2015;52:172–83. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchie EK, Feldman EJ, Christos PJ, et al. Decitabine in patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2003–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.762093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum W, Garzon R, Klisovic RB, et al. Clinical response and miR-29b predictive significance in older AML patients treated with a 10-day schedule of decitabine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7473–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002650107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen L, Kantarjian H, Guo Y, et al. DNA methylation predicts survival and response to therapy in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:605–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan P, Frankhouser D, Murphy M, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling in decitabine-treated patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:2466–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song LX, Xu L, Li X, et al. Clinical outcome of treatment with a combined regimen of decitabine and aclacinomycin/ cytarabine for patients with refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1879–86. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1550-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzeler KH, Walker A, Geyer S, et al. DNMT3A mutations and response to the hypomethylating agent decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26:1106–7. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiNardo CD, Patel KP, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Lack of association of IDH1, IDH2 and DNMT3A mutations with outcome in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with hypomethylating agents. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:1925–9. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.855309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bejar R, Lord A, Stevenson K, et al. TET2 mutations predict response to hypomethylating agents in myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Blood. 2014;124:2705–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-582809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klco JM, Miller CA, Griffith M, et al. Association between mutation clearance after induction therapy and outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA. 2015;314:811–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4642–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108:419–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2059–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cashen AF, Schiller GJ, O'Donnell MR, DiPersio JF. Multicenter, phase II study of decitabine for the first-line treatment of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:556–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong TN, Miller CA, Klco JM, et al. Rapid expansion of preexisting nonleukemic hematopoietic clones frequently follows induction therapy for de novo AML. Blood. 2016;127:893–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-677021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2477–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2488–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laurie CC, Laurie CA, Rice K, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism from birth to old age and its relationship to cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:642–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hemato poietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med. 2014;20:1472–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravandi F, Issa JP, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Superior outcome with hypomethylating therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodys-plastic syndrome and chromosome 5 and 7 abnormalities. Cancer. 2009;115:5746–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lübbert M, Suciu S, Hagemeijer A, et al. Decitabine improves progression-free survival in older high-risk MDS patients with multiple autosomal monosomies: results of a subgroup analysis of the randomized phase III study 06011 of the EORTC Leukemia Cooperative Group and German MDS Study Group. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:191–9. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lafouresse F, Bellard E, Laurent C, et al. L-selectin controls trafficking of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells in lymph node high endothelial venules in vivo. Blood. 2015;126:1336–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-626291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowen D, Groves MJ, Burnett AK, et al. TP53 gene mutation is frequent in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and complex karyotype, and is associated with very poor prognosis. Leukemia. 2009;23:203–6. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Middeke JM, Herold S, Rücker-Braun E, et al. TP53 mutation in patients with high-risk acute myeloid leukaemia treated with allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:914–22. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christman JK. 5-Azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine as inhibitors of DNA methylation: mechanistic studies and their implications for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2002;21:5483–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabrero M, Jabbour E, Ravandi F, et al. Discontinuation of hypomethylating agent therapy in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes or acute myelogenous leukemia in complete remission or partial response: retrospective analysis of survival after long-term follow-up. Leuk Res. 2015;39:520–4. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klco JM, Spencer DH, Lamprecht TL, et al. Genomic impact of transient low-dose decitabine treatment on primary AML cells. Blood. 2013;121:1633–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-459313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roulois D, Loo Yau H, Singhania R, et al. DNA-demethylating agents target colorectal cancer cells by inducing viral mimicry by endogenous transcripts. Cell. 2015;162:961–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi J, Ritchey J, Prior JL, et al. In vivo administration of hypomethylating agents mitigate graft-versus-host disease without sacrificing graft-versus-leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:129–39. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.