Abstract

Deriving biofuels and other lipoid products from algae is a promising future technology directly addressing global issues of atmospheric CO2 balance. To better understand the metabolism of triglyceride synthesis in algae, we examined their metabolic origins in the model species, Coccomyxa subellipsoidea C169, using stable isotopic labeling. Labeling patterns arising from [U-13C]glucose, 13CO2, or D2O supplementation were analyzed by GC-MS and/or LC-MS over time courses during nitrogen starvation to address the roles of catabolic carbon recycling, acyl chain redistribution, and de novo fatty acid (FA) synthesis during the expansion of the lipid bodies. The metabolic origin of stress-induced triglyceride was found to be a continuous 8:2 ratio between de novo synthesized FA and acyl chain transfer from pre-stressed membrane lipids with little input from lipid remodeling. Membrane lipids were continually synthesized with associated acyl chain editing during nitrogen stress, in contrast to an overall decrease in total membrane lipid. The incorporation rates of de novo synthesized FA into lipid classes were measured over a time course of nitrogen starvation. The synthesis of triglycerides, phospholipids, and galactolipids followed a two-stage pattern where nitrogen starvation resulted in a 2.5-fold increase followed by a gradual decline. Acyl chain flux into membrane lipids was dominant in the first stage followed by triglycerides. These data indicate that the level of metabolic control that determines acyl chain flux between membrane lipids and triglycerides during nitrogen stress relies primarily on the Kennedy pathway and de novo FA synthesis with limited, defined input from acyl editing reactions.

Keywords: algae, fatty acid, membrane, phospholipid, triglyceride, galactolipid, metabolic flux

Introduction

Oil production from algal feedstocks is a promising answer to the dwindling supply of easily extractable petroleum, one that is readily transferrable to the current transportation infrastructure and recycling of CO2 emissions. Algae have high growth rates and accumulate triglycerides (TG)2 in excess of crop seed oil when subjected to abiotic stress, most notably nitrogen deficiency (1). The caveat is a tradeoff between cellular TG quantities and reproductive growth. In nature, oil accumulation is linearly correlated with, and may be caused by, a cessation or slowing of the cell cycle (2–4). Engineering algae to produce oil on demand is needed for improving process yields and necessitates a thorough understanding of the biochemistry underlying oil accumulation for the development of strategies to attain this goal (5).

Most prokaryotic and all eukaryotic glycerolipids are commonly configured from two fatty acyl chains and one of a wide variety of polar functional groups esterified to a glycerol molecule. Differences in the acyl moiety chain length and the number of double bonds and in the size and charge of the polar head group result in many thousands of theoretical variations. Chemical differences between membrane lipids result in unique intracellular environments required for the specialized functions of organelles and cellular responsiveness to environmental changes (6). Specific enzymes mediate the replacement of membrane lipid acyl groups in plants, removing unsaturated FA and replacing them with mono- or polyunsaturated FA and dynamically adjusting membrane chemistry through subtle alterations in acyl group architecture. An important result of this action is the efficient translocation of de novo synthesized fatty acids from the chloroplast to the extra-chloroplast membrane lipid pool (7). Acyl editing reactions include the Lands cycle (8), governing the removal of an unsaturated sn-2 position acyl moiety of phosphatidylcholine (PC) by hydrolysis via phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and replaced from the acyl-CoA pool by lyso-phosphatidylcholine acyltransferase (LPCAT). The sn-2 position of PC can also be transferred directly to the sn-3 position of diacylglycerol (DAG) to form TG through the action of phosphatidylcholine:diacylglycerol transacylase (PDAT) (9). The LPCAT reaction is reversible in plants, so the Lands cycle can be carried out by this enzyme alone (10). The reconversion of lyso-phosphatidylcholine generated by PDAT into a PC requires LPCAT as well, making it a central enzyme in acyl editing reactions.

In contrast to acyl editing, lipid remodeling reactions alter membranes by removing and replacing the polar head group. In Arabidopsis thaliana the most extreme example of this is the majority replacement of PC during inorganic phosphate (Pi) stress with a galactolipid originating from the chloroplast (11). During Pi starvation, PC is hydrolyzed to phosphocholine and DAG by either phospholipase C or D, transported to the outer chloroplast membrane, and incorporated into the galactolipid synthetic pathway (12, 13). Null mutations of LPCAT1/LPCAT2 in A. thaliana lead to the recycling of lyso-phosphatidylcholine by removal of the choline head group and reintegration into the Kennedy pathway, resulting in significant alterations to the TG pool (14). These alterations could also be the result of increased activity of phosphatidylcholine:diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase (PDCT), which catalyzes the removal of the choline head group from intact PC allowing the conversion of the resulting DAG molecule to TG through diacylglycerol acyltransferase (15). PDCT has been found to be mainly responsible for the interconversion of PC and DAG and shown to be required for about half of the incorporation of hydroxylated FA into the TG pool in transgenic A. thaliana (16). Overexpression of PDCT in A. thaliana seeds also results in a 20% increase in polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) content (17).

Lipid droplets are the repository of acyl chains thought to enter the TG pool through various pathways, but the relative input from membrane lipid recycling and de novo synthesis still remains unclear. In algae, the protein and/or transcript abundance of the Kennedy pathway enzymes glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, lyso-phosphatidyl acyltransferase, phosphatidic acid phosphatase, and diacylglycerol acyltransferase increase alongside acyl editing enzymes PDAT and LPCAT during nitrogen stress (9, 18–21). The presence of PUFA is also considered indicative of membrane acyl chain recycling into the TG pool, because FA desaturation reactions in plants occur mostly on FA incorporated into membrane lipids, and there is no evidence to the contrary in algae (22–25). Although acyl editing and lipid remodeling pathways are known to take part in TG accumulation, it is necessary to quantify these inputs to determine how important these pathways are to the overall yield. FA synthesis inputs from carbon recycled after the catabolism of biomolecules (e.g. proteins) and carbon fixed through photosynthesis are similarly understudied, yet these aspects also remain important factors in determining how best to alter algal metabolism to enhance TG synthesis.

Coccomyxa subellipsoidea C169 is a free-living asexual freshwater green algal species with a fully sequenced genome (26) and is closely related to the genus Chlorella, sharing 63% of genes with Chlorella variabilis NC64A (26, 27). Chlorella species have emerged as strong candidates for algal biofuel production due to their high growth rates (28–31), and of note is that biodiesel derived from C. subellipsoidea has been evaluated favorably (32). Originally collected in Antarctica, C. subellipsoidea is being considered as a possible cold-tolerant production species (26). This is especially important for cooler geographical regions, because controlling water temperature to maximize the growth rate can be a major energy expense in large scale production (33). Aside from the optimal growth temperature, C. subellipsoidea exhibits lipid profiles and stress-induced metabolic trends consistent with other microalgal species (34, 35). In a previous study, we demonstrated that acyl group chain length, positioning, and double bond content in TG present as a fixed ratio during nitrogen stress (34). This suggests a significant role for acyl editing throughout nitrogen stress rather than synthesis through the sequential acylation of glycerol by newly synthesized acyl chains. Nitrogen stress-induced TG is also highly enriched in oleic acid in C. subellipsoidea, suggesting that fatty acid synthesis still provides the majority of acyl chains for TG synthesis rather than redistribution from membrane lipids.

In the present work, pathways of acyl chain flux contributing to oil synthesis were analyzed during nitrogen stress using four different stable isotopic labeling schemes applied to C. subellipsoidea C169. Lipid classes were separated to distinguish between the biochemistry of membrane maintenance/catabolism and TG anabolism, enabling the indirect analysis of pathways contributing to oil accumulation. Neutral lipids containing >95% TG and a small amount of sterol ester were separated from crude lipid extracts by silica column chromatography. Membrane lipids were further separated into galactolipids intrinsic to plastids in algae and phospholipids that are mostly extrinsic of plastids (36). Significant structural changes in plastid architecture during nitrogen stress are associated with alterations in both total and relative amounts of the chloroplast-specific membrane lipids. This has been suggested to indicate that their metabolism differs from other membrane lipids (36–38). Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) is reduced dramatically during thylakoid degradation, probably to avoid destabilizing plastid membrane integrity and function due to its conical steric profile as the chloroplast decreases in size (34, 39).

This study is the first to show that FA synthesis and subsequent incorporation into membrane lipids continues during nitrogen stress and moreover to demonstrate that the expansion of lipid droplets requires de novo FA synthesis and distinct patterns of acyl chain flux between membrane lipids and TG. The contributions of acyl editing, membrane catabolism, and lipid remodeling reactions were further quantified in relation to acyl chain flux into oil. A detailed analysis of FA synthesis and incorporation rates into lipid classes over the course of nitrogen starvation and recovery demonstrates two distinct stages of nitrogen stress in which membrane lipids act as alternative sinks of newly synthesized FA, significantly outcompeting TG in the early stage.

Results

Overview

Five labeling regimes were employed using 13C and deuterium stable isotopes, which were designed to highlight specific aspects of acyl chain flux. Metabolites were generally labeled through mixotrophic growth using [U-13C] glucose, and changes in the labeling patterns of lipids and lipid-associated glycerol analyzed during label-free nitrogen starvation. This approach facilitated study of acyl chain transfer from membrane lipids that could contribute to TG synthesis. Continuous labeling with 13CO2 informed on the roles of photosynthetic C fixation and catalytic C recycling. D2O labeling measured the general flux of acyl chains into TGs and through membrane lipids. Finally, much shorter time courses of D2O labeling were used to quantify the incorporation rates of de novo synthesized FA into complex lipids in the context of abiotic stress.

Nitrogen Starvation after [U-13C]Glucose Prelabeling

The glycerol and FA moieties of TG, galactolipid (GL), and phospholipid (PL) pools were analyzed for the relative incorporation of pre-stress and newly synthesized glycerol into complex lipids during nitrogen starvation by measuring the changes in percentage labeling and 13C distribution. The goal of these experiments was to quantify the amount of TG derived from the interconversion of other complex lipids. C. subellipsoidea was 13C-labeled for this analysis under normal, unstressed conditions by mixotrophic growth with 25 mm uniformly labeled [13C]glucose for 1 week starting from a low initial cell density of 3 × 105 cells ml−1. Labeling in the resulting stationary phase cultures was evident in the biomolecules analyzed but varied in degree due to differences in the propensity of the associated biosynthetic pathways to incorporate carbon from the supplied [U-13C]glucose or unlabeled, photosynthetically derived molecules (Figs. 1 and 2). GC-MS analysis demonstrated the presence of 13C in 85% of the glycerol and 95% of the FA molecules. The percentage labeling in glycerol was >63% and in FA was >50%. The 13C-labeled biomass was subjected to nitrogen starvation without further addition of label, and changes in 13C labeling in the TG, GL, and PL pools due to the addition of newly assimilated 12C or the movement of labeled, previously synthesized moieties were measured after 1 week. Glucose was chosen for the simultaneous labeling of acyl chains and glycerol based on a recent plant-based study that demonstrated a lack of incorporation of label into fatty acids using glycerol itself (40). The incorporation of stable isotopically labeled glycerol into the TG pool as a proxy for the activity of complex lipid remodeling enzymes is an established technique (41).

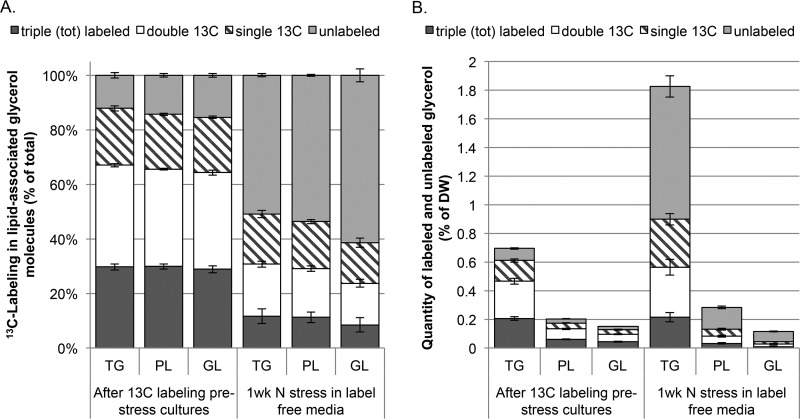

FIGURE 1.

Relative and absolute quantities of 13C-labeled glycerol from complex lipid hydrolysis after labeling with [U-13C]glucose during stress-free growth and after 1 week of label-free nitrogen starvation. Data are shown for the glycerol moieties of three lipid classes separated by polarity, TG, GL, and PL after prelabeling with 13C and a subsequent 1 week of growth in label-free nitrogen-free media. Isotopic distributions from GC-MS analysis of derivatized glycerol were used to generate the amount of unlabeled, single 13C-labeled, double 13C-labeled, and totally labeled glycerol as a percentage of the total quantity (A) and as a percentage of the extracted dry weight of algae (B). Error bars represent S.D.; n = 3.

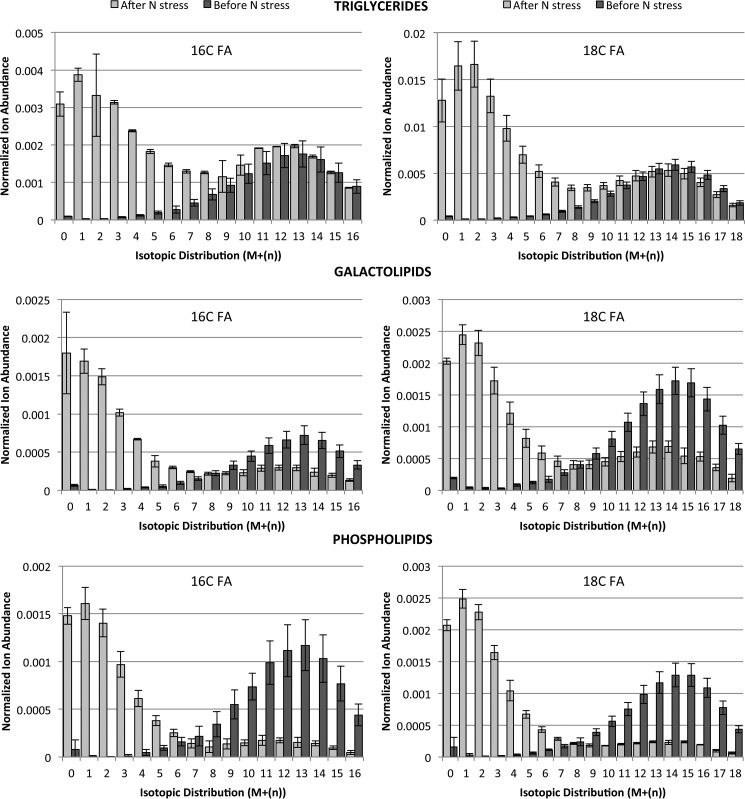

FIGURE 2.

13C isotopomer distributions of catalytically saturated fatty acids from isolated lipid pools. FA labeling was analyzed by GC-MS from C. subellipsoidea labeled with [U-13C]glucose for 1 week (before nitrogen stress) and after 1 week of nitrogen starvation (after nitrogen stress). Lipid extracts were separated into triglyceride, galactolipid, and phospholipid pools by column chromatography and then saturated before conversion to methyl esters and analysis. Fatty acid isotopomers are normalized by monoisotopic mass and their distribution as M + (n) where n is equal to the number of incorporated 13C atoms. Error bars represent S.D. of three replicate cultures.

One week of [13C]glucose labeling resulted in similar relative quantities of unlabeled, single, double, or fully 13C-labeled glycerol isotopologs hydrolyzed from neutral lipid, GL, and PL pools (Fig. 1). Within the lipid classes analyzed, there was an approximate ratio of 3:3.5:2:1.5 among three 13C-labeled, two 13C-labeled, one 13C-labeled, and fully unlabeled glycerol. Following a week of nitrogen starvation in the absence of [13C]glucose, there was an increase in the relative percentage of unlabeled glycerol synthesized during nitrogen stress, suggesting the dominant role of the Kennedy pathway in complex lipid synthesis during this time. The total quantity of measured glycerol increased 2.1 ± 0.2-fold with 99.8 ± 9% of this increase in the TG pool under nitrogen starvation conditions. More than half of the glycerol in the PL and GL pools was replaced by unlabeled glycerol during this period, whereas there was essentially no change in quantity, indicating an equivalent efflux of existing and influx of newly synthesized glycerol. This data agree with the FA labeling data and suggest an efflux of both preexisting acyl chains and glycerol, possibly esterified into complex lipids. However, virtually all of the TG produced during the week of nitrogen starvation was associated with either unlabeled or single 13C-labeled glycerol, suggesting the dominant role of the Kennedy pathway rather than lipid remodeling reactions in complex lipid synthesis during this time. The double and triple 13C-labeled glycerol quantities did not change appreciably in the TG pool during nitrogen stress (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the quantity of singly labeled glycerol increased nearly 2-fold, which is much more than can be accounted for by transfer from the phospholipids and is likely the result of new synthesis utilizing previously captured carbon. Loss of 13C from the PL pool accounted for only 6.8% of the gains of singly 13C-labeled glycerol in TG, whereas the incorporation of unlabeled and singly 13C-labeled glycerol together accounted for 92% of the newly synthesized TG. The measured smaller changes in double and triple 13C-labeled glycerol content support the conclusion that there was little transfer of pre-existing glycerol from the membrane lipids into the TG pool under nitrogen starvation growth conditions.

We next determined the patterns of labeling and relative abundance of 13C in C16 and C18 fatty acids in the TG, GL, and PL pools after 7 days with [U-13C]glucose in nitrogen-replete media and after 7 days of nitrogen starvation in the absence of label to analyze the incorporation of de novo synthesized FA and the movement of FA moieties between lipid classes. The relative abundance of the different molecular ions for the C16 and C18 fatty acids was measured by GC-MS, and molecular ion signal intensities were normalized to the monoisotopic ion signal of an internal standard and the dry weights of the algal samples. Post-labeling molecular ion abundances of the C16 and C18 acyl chains in all three classes of lipid had parabolic patterns with apexes at M + 13 for C16 FA and M + 14 for C18 FA, where M is monoisotopic mass. After 7 days of mixotrophic labeling with [U-13C]glucose, ∼94% of the ion abundance counts in the C16 and C18 FA were M + 7 or greater (Fig. 2). Of particular importance was the finding that label-free nitrogen starvation produced a second set of distinguishable ion abundances evident in all three classes of lipids between M + 0 and M + 7, indicative of de novo fatty acid synthesis and were easily distinguishable from pre-stress, highly labeled FA. Quantitative analysis of these molecular ion groups showed a 78% reduction of pre-stress FA in the PL pool, a 54% reduction in the GL pool, and a 12% increase in the TG pool. During nitrogen starvation, the efflux of labeled acyl chains was greatest from the PL pool; nearly all of the phospholipid acyl chains were replaced over the 7 days of nitrogen starvation. The data indicate a significant flux of FA chains through membrane lipids during nitrogen starvation and that the majority of fatty acids in TG synthesis are from de novo synthesis from photosynthetically fixed carbon. An average of 11% of the carbon content of TG as C16 and C18 fatty acids synthesized during nitrogen starvation was labeled with 13C, suggesting the incorporation of previously reduced carbon also contributes to stress-induced lipogenesis (Table 1). These conclusions were further tested using 13CO2 labeling.

TABLE 1.

Percent of carbon from de novo synthesized FA derived from the catabolism of pre-stress biomolecules

| C16 FA | C18 FA | |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| Triglycerides | 11.8 ± 0.44 | 10.4 ± 0.23 |

| Galactolipids | 9.0 ± 0.78 | 9.4 ± 0.38 |

| Phospholipids | 9.1 ± 0.35 | 9.0 ± 0.27 |

13CO2 Labeling during Nitrogen Starvation

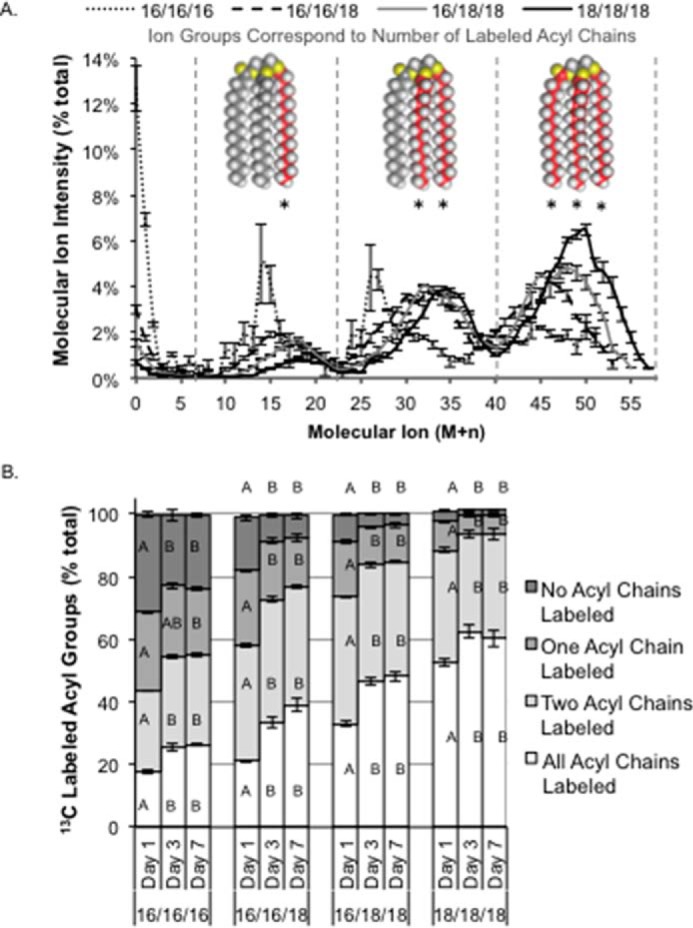

Acyl chain remodeling was addressed next in relation to TG synthesis in C. subellipsoidea following 13CO2 labeling during nitrogen starvation and analysis of intact, catalytically saturated molecules by LC-MS. There were three distinct molecular ion domains separable by ∼15 m/z units, similar to the labeled acyl chains following growth in the presence of [U-13C]glucose, which represent 13C labeling from photosynthetically fixed carbon in one, two, or three of the acyl chains in TG (Fig. 3A). The abundance of 13C labeling in the acyl chains, indicated by one, two, or three asterisks in Fig. 3A, were analyzed at days 1, 3, and 7 over the 7-day time course of nitrogen starvation and calculated as relative percentages (Fig. 3B). The quantity of unlabeled acyl chains in each of the TG species analyzed was shown to be inversely correlated with the C16 FA content (Fig. 3B). Approximately 2% of the TG(18/18/18) and 24% of the TG(16/16/16) acyl chains were unlabeled after 7 days. The total 13C labeling of TG species varied with C16 FA; TG(18/18/18) had a maximum labeling with 13C of 72% compared with 45% 13C labeling in the TG(16/16/16) chains (Fig. 3A). No statistically significant changes were measured by pairwise comparisons (ANOVA; p < 0.05) of time points within TG molecular species after day 1, and by day 3 further incorporation of labeled and unlabeled FA was in proportional steady states (Fig. 3B). These findings mirror our previous experimental results demonstrating that the TG C16/C18 acyl chain ratio remained stable after 3 days and through 7 days of subsequent nitrogen deprivation (33), supporting the concept of a consistent and stable system-wide set of reactions leading to TG production during abiotic stress in this species.

FIGURE 3.

Incorporation of 13C-labeled and unlabeled acyl chains in TAG molecular species from 13CO2 labeling. Cultures of C. subellipsoidea were labeled with 100% [13C]bicarbonate in nitrogen-free media with samples removed on days 1, 3, and 7. A, molecular ion intensities showing peak distributions corresponding to TAG molecules with one, two, or three labeled fatty acyl groups (indicated by asterisks under space-filling models of tristearin) after 7 days of 13C labeling. B, the sum of ion intensities within each peak representing molecules with three, two, one, or no labeled acyl chains was calculated relative to the total for each TG molecular species (% total). Error bars represent S.E. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA, and significant differences are shown here as A and B, whereas AB is not significantly different from A or B; n = 3.

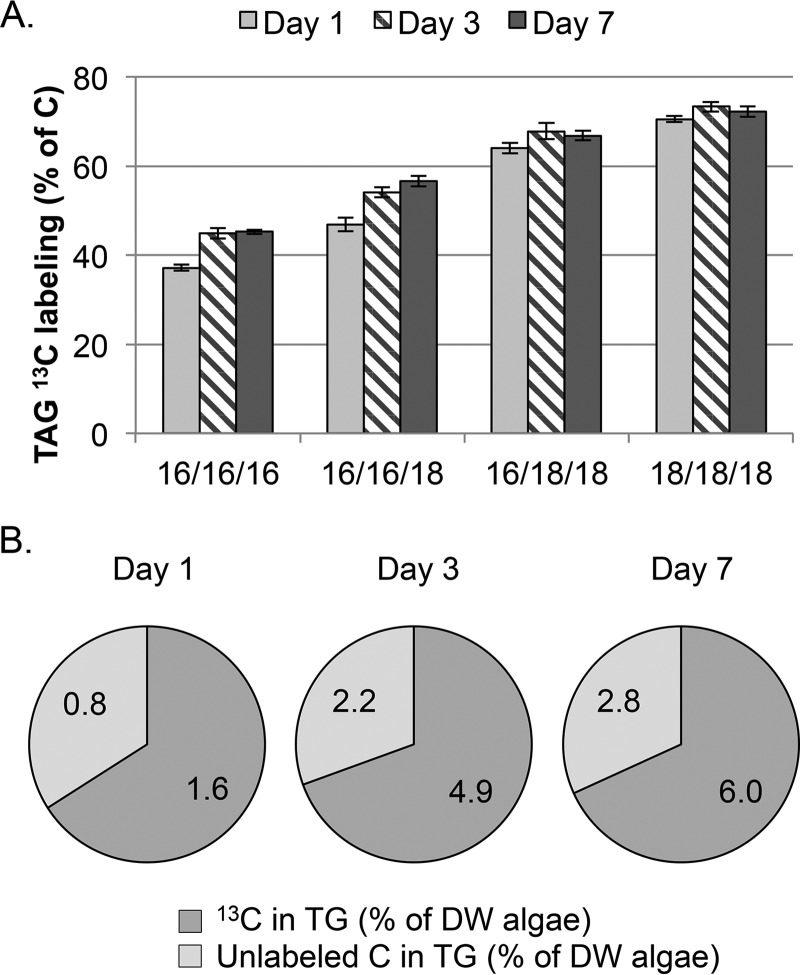

The patterns of 13C labeling related to the quantity of TG species specifically demonstrate that the unlabeled FA in TG is primarily C16 (Fig. 3B). Although the quantity of TG increases over the 7-day nitrogen starvation time course, the total 13C labeling of TG was 66, 70, and 68% on days 1, 3, and 7, respectively (Fig. 4A). There was a continuous input of unlabeled carbon in the TG pool over the entire course of nitrogen starvation evident in both 13C labeling studies. This was ∼90% accounted for from the 13CO2 labeling study as incorporation of entirely unlabeled FA. Unlabeled carbon was also incorporated into labeled FA, which can only be derived from catabolic recycling of pre-stress reduced carbon compounds, and ranged from 5 to 14% of the total TG pool. This range of unlabeled carbon corresponds well to the range of 9 to 12% determined by prelabeling cultures with [U-13C]glucose. This indicates both a continual insertion of acyl chains synthesized prior to nitrogen starvation and catabolically derived unlabeled carbon in fatty acid synthesis that contributes to the TG pool throughout the 7 day nitrogen starvation period (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

13C labeling from 13CO2 of TG molecular species during a time course of nitrogen starvation. Labeled TG molecular species were separated chromatographically and isolated, and the 13C content was measured by LC-MS. Data are shown as 13C labeling in TG molecular species (A) and the relative amount of 13C and unlabeled 12C in the total TG pool (B). The numbers indicate the quantity of 13C (dark gray) and 12C (light gray) in the TG pool as a percentage of the total dry weight of algae. Error bars represent S.D.; n = 3.

Analysis of Membrane Lipid Flux Using Deuterium Labeling

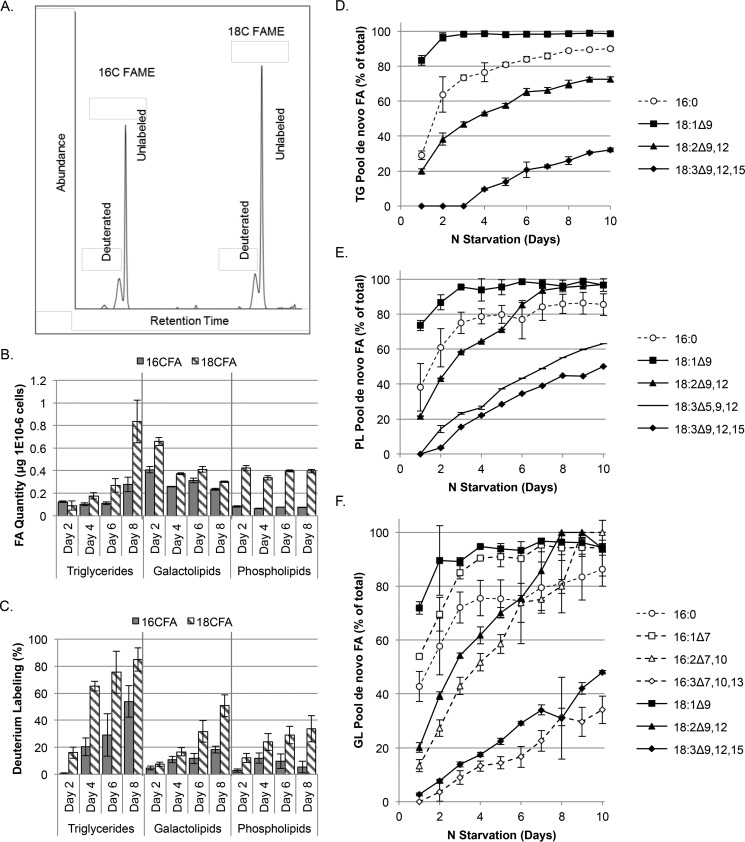

The experimental data presented above is fully consistent with the conclusion that de novo fatty acid synthesis continues during nitrogen starvation with the subsequent flux of these fatty acids into the TG pool. To address de novo fatty acid synthesis directly, continuously supplied D2O (30%) was used to trace the flux of newly synthesized acyl chains between major lipid classes over an 8-day nitrogen starvation time course. Deuterium-labeled lipid extracts were separated by column chromatography into TG, GL, and PL fractions as detailed above. These were either untreated to analyze specific FA species or catalytically hydrogenated to facilitate increased signal intensities by combining saturated and unsaturated C16 and C18 FA into single peaks. Analysis of the resultant fatty acid methyl esters by GC-MS enabled the quantification of FA with or without deuterium incorporation due to the significant differences in time resolution between the labeled and unlabeled peaks (Fig. 5A). The relative quantification of deuterium-labeled FA was compared with absolute FA quantifications to analyze acyl chain flux through lipid pools (Fig. 5). Cultures were analyzed every other day over the 8-day time course of nitrogen starvation. The TG pool increased by 5.3-fold between days 2 and 8, and the GL and PL pools decreased by 50 and 7%, respectively (Fig. 5B). These quantitative changes were associated with increased deuterium labeling over the time course for all lipid pools examined (Fig. 5C). In agreement with the 13C labeling data, de novo synthesis of C18 FA was much greater than C16 FA and C18 incorporation into the TG pool and accounted for ∼85% of the total fatty acids synthesized by day 8. These results were comparable with the 13CO2 labeling results that showed ∼85% of the FA were labeled at the end of the time course. Although the absolute quantities decreased during nitrogen starvation, 51 and 34% of the FA in the GL and PL pools, respectively, were synthesized during nitrogen stress. These results indicate that the influx of de novo fatty acids was comparable with the efflux of acyl chains from the PL and GL pools; however there was discrepancy in the amount of PL synthesized between experiments. Data from the [U-13C]glucose labeling experiment indicated a 38% increase in the absolute quantity of PL (Fig. 1B). The GL pool was also not as reduced by nitrogen stress, likely because it was already somewhat reduced due to the availability of glucose in the media. The GL acyl chains became labeled despite the decrease in the amount of GL during N starvation, which supports the notion that both influx and efflux of acyl chains continues to occur with the coincident degradation of chloroplast membranes (34).

FIGURE 5.

Deuterium labeling of membrane and storage lipid fatty acids during nitrogen starvation. A, GC-MS chromatogram of hydrogenated, deuterium-labeled FAME, demonstrating the shift in retention time. B and C, batch cultures were labeled with 30% D2O in nitrogen-free medium, and lipids were analyzed every 2 days for a total of 8 days. Lipids were extracted, separated by class using silica columns, catalytically hydrogenated, and then converted to fatty acid methyl esters. B, quantities of triglyceride, galactolipid, and phospholipid pools were measured by LC-MS/MS from unlabeled cultures grown in parallel. C, the percent of labeling was additionally measured by GC-MS analysis. Standard errors were calculated from five independent cultures per condition. D–F, C. subellipsoidea was labeled with 30% D2O in nitrogen-free medium and grown in a bioreactor that controlled light, temperature, gas availability, and pH. Samples were taken daily, and lipids were extracted and separated into neutral (D), galactolipid (E), and phospholipid (F) classes by silica column. FAME were generated, and the percentage of labeled fatty acid was measured by GC-MS from technical triplicate samples. Error bars represent S.D.; n = 3.

To further these studies, bioreactor based experiments were conducted over the 10-day starvation period to produce sufficient algal biomass for a more comprehensive analysis of the different unsaturated FA species. In these experiments, 30% of the D2O was supplied at the beginning of nitrogen starvation, and samples were then taken daily for 10 days (Fig. 5, D and E). In all three lipid pools analyzed, oleic acid (18:1Δ9) was essentially completely labeled by day 4, and the patterns were strikingly similar between the membrane lipids and TG. After day 1, pairwise comparisons (ANOVA, p < 0.05) showed no significant differences between labeling in the PL and TG pool oleic acids; however GL labeling was generally lower on most days. Palmitic acid (C16:0) was not significantly different between the three lipid pools over the 10-day time course. These data suggest that the incorporation of de novo synthesized acyl chains is at equilibrium between lipid classes during nitrogen starvation. In the membrane lipids (PL and GL), linoleic acid (C18:2Δ9,12) was nearly completely labeled by day 8; labeling of α-linolenic acid (C18:3Δ9,12,15) was reduced and reached only ∼50% labeling by day 10 (Fig. 5, E and F). By contrast, the labeling of α-linolenic acid was lower (32%) in the TG pool on day 10. The signal to noise ratio was too high to accurately measure labeling in unsaturated C16 FA into the PL and TG pools. In the GL pool, palmitoleic acid (C16:1) was more rapidly labeled than palmitic acid (C16:0) (Fig. 5F).

Analysis of FA Synthesis and Incorporation Rates into the Three Lipid Pools during Nitrogen Stress

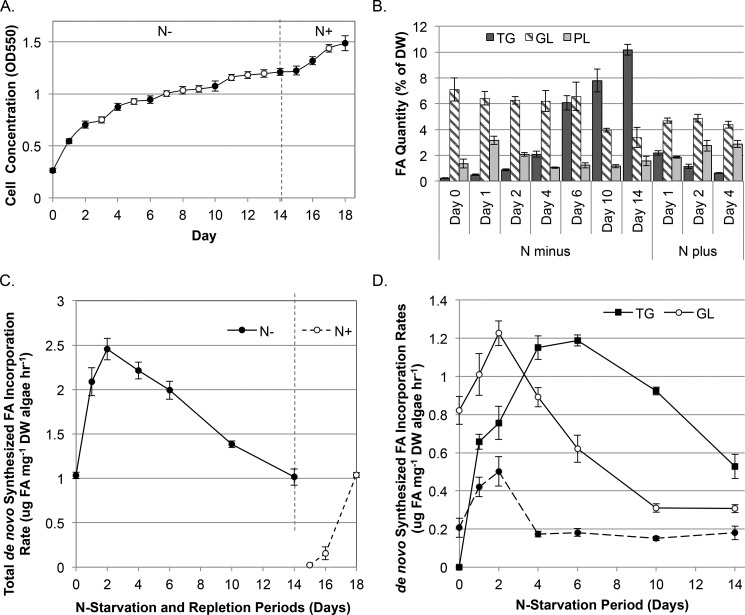

We next addressed the incorporation rates of de novo synthesized FA into the TG, GL, and PL pools over a total of 10 short time courses where samples were taken at 3, 6, 9, and 12 h after the addition of 20% D2O (65). These time courses were conducted after 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, and 14 days of nitrogen starvation and 1, 2, and 4 days of nitrogen recovery (Fig. 6A). As expected from previous studies, the TG pool increased nearly 10-fold during nitrogen starvation, and the total quantity of FA in the GL and PL pools was reduced by ∼50% by day 14 of nitrogen stress (Fig. 6B). Incorporation rates measured during nitrogen stress were compared with control rates measured during unstressed mid-exponential phase growth, referred to as time zero (Fig. 6, C and D).

FIGURE 6.

Incorporation rates of de novo synthesized acyl chains into major lipid classes over a time course of nitrogen starvation and recovery. Cultures of C. subellipsoidea labeled with D2O on days 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, and 14 of a nitrogen starvation time course and the rate of labeling in the FA assessed after 3, 6, 9, and 12 h to determine the rate of incorporation. Samples were extracted and separated into TG, GL, and PL by column chromatography, and the methyl esters were analyzed by GC-MS. A, OD was measured once daily over the 2-week nitrogen starvation time course. Nitrate was added to the cultures on day 14, and the results were analyzed over the subsequent 4 days. Closed circles indicate FA synthesis rate measurement time points. B, the total FA quantity was analyzed for the major lipid pools assessed (TG, GL, and PL). C, the total FA incorporation rate into all lipid classes analyzed was assessed as a measurement of FA synthetic rates over the time course. D, incorporation of de novo synthesized FA into the lipid pools analyzed. Error bars represent S.D.; n = 4 independent cultures.

The studies addressing FA synthesis revealed two distinguishing stages during nitrogen starvation. The first was characterized by an initial and rapid 2.4-fold increase in FA synthesis over the first 2 days and the second stage by a steady decline to the initial rate by day 14 (Fig. 6C). This second-phase decrease in the FA synthetic rate was linear from days 2 through 14 of nitrogen starvation (5% per day (R2 = 0.99)) and coincided with previously published reductions in both chlorophyll and MGDG content, which lead to a diminished photosynthetic capacity (22, 34, 42). Following the readdition of nitrogen on day 14, de novo FA synthesis was not detectable by deuterium labeling on days 14–16 but returned to the pre-starvation rates within 4 days of nitrogen readdition (Fig. 6C). This initial cessation was seen in all lipid pools, indicating that the influx of C18 FA into the GL during recovery from nitrogen stress demonstrated previously in this species (34) originates from the TG pool and coincides with the total repression of FA synthesis.

The onset of nitrogen starvation led to an increase in the rate of de novo synthesized FA incorporation into both chloroplastic and extraplastidic membrane lipids, with peak synthetic rates, measured on day 2 for both GL and PL pools (Fig. 6D), akin to total fatty acid synthesis rates (Fig. 6C). The influx of de novo synthesized FA into the GL and PL as determined using continuous D2O labeling (Fig. 5) is apparently skewed toward the earlier phase rather than being uniform throughout nitrogen stress. The incorporation of fatty acids into the TG pool was delayed compared with the PL and GL pools and increased in quantity, peaking at day 6, through a linear increase of 0.5% of DW algae day−1 (R2 = 0.99). This suggests that the incorporation into membrane lipids is essentially replaced by incorporation into TG during the second phase of nitrogen starvation. Incorporation rates declined in the TG pool after day 6 in a linear fashion (R2 = 0.99) at −0.083 μg lipid mg−1 DW algae h−1, indicating a decrease in carbon assimilation during extended nitrogen stress and thus lower TG accumulation rates.

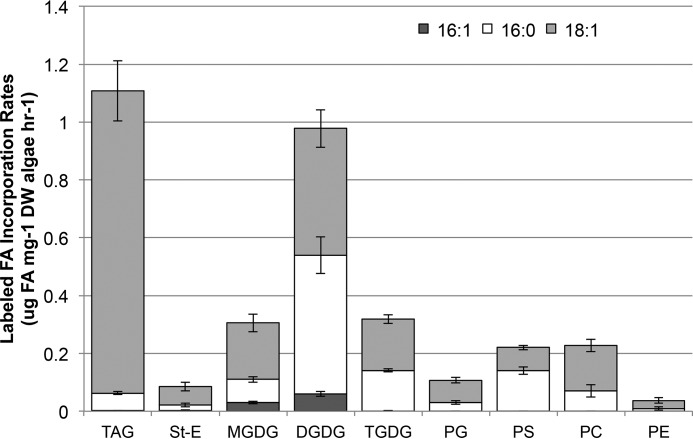

The high rates of de novo synthesized acyl chain incorporation into membrane lipids led us to further separate the TG, GL, and PL fractions into their major lipid class constituents and to define their relative contributions of de novo acyl chain incorporation. Nine lipid classes were isolated using TLC after 2 days of nitrogen starvation under D2O labeling conditions coincident with peaks in membrane lipid incorporation and the overall FA synthesis rates as noted above (Fig. 6, C and D). The fatty acids from the different lipid fractions were analyzed as their methyl esters by GC-MS at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h, and the resultant data were fitted to a least squares function. The resultant slopes were used to define the incorporation rates of the newly synthesized fatty acids (Fig. 7). Labeling was detected only for oleic, palmitic, and palmitoleic methyl esters because of the low concentrations of the individual lipid classes including the TG and sterol ester, galactolipids MGDG, digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), and trigalactosyldiacylglycerol (TGDG), and phospholipids PC, phosphatidylserine (PS), phsophatidylglycerol (PG), and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). The total rates measured in these experiments were about 30% higher than those measured for the longer time courses; however their relative ratios were very similar. The TG:GL:PL ratios of incorporation rates were 1.2:1.6:0.6 (μg lipid mg−1 DW algae h−1) in this experiment compared with 0.8:1.2:0.5 (μg lipid mg−1 DW algae h−1) on day 2 of the time course. A small amount (7%) of the FA labeling measured in the neutral lipid pool was from sterol esters, but this pool otherwise comprised TG. The total incorporation rate into DGDG was more than 3-fold greater than MGDG, which was equivalent to TGDG. Incorporation into DGDG comprised 61% of the total GL pool rate, consistent with previous studies where MGDG declined faster than DGDG during nitrogen stress (33). In the PL pool, the rates of incorporation into PC and PS were nearly equal, with PG about half of that. Half of the GL incorporation rate was from C16 FA, demonstrating that palmitic acid is incorporated primarily into chloroplast-derived complex lipids.

FIGURE 7.

Incorporation rates of de novo synthesized FA in nine lipid classes after 2 days of nitrogen starvation. Cultures were labeled with D2O after 2 days of nitrogen stress, and acyl chain labeling was analyzed in the lipidome at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h to determine incorporation rates. Lipid extracts were separated by TLC before synthesis of methyl esters and GC-MS analysis of TAG, sterol esters (St-E), MGDG, DGDG, TGDG, PG, PS, PC, and PE. Shown are the rates of incorporation of de novo synthesized oleoyl (18:1), palmitoyl (16:0), and palmitoleoyl (16:1) acyl chains into specified lipid classes. Error bars represent S.D.; n = 4 independent cultures.

Discussion

The economic viability of biofuel production from algal sources will depend largely on current scientific efforts to understand the mechanistic details underpinning TG accumulation under conditions where reproductive growth is limited, as occurs through nitrogen limitation, which will inform the development of strategies to replicate this phenotype free of growth restrictions (3, 5). Stable isotopic labeling of C. subellipsoidea has yielded novel flux information, especially in relation to TG synthesis, that can be applied directly to the development of strategies for maximizing oil production in algae. This is the first study that measures de novo FA synthesis during nitrogen stress, defines the rate at which newly synthesized FA are trafficked into complex lipids (TG, PL, and GL), and demonstrates both membrane lipid synthesis and turnover during nitrogen stress. Several results important to algal lipid biochemistry during nitrogen starvation have been revealed, including the following. 1) There is very little to no membrane head group remodeling component to TG synthesis. 20 More than 90% of TG is the product of the Kennedy pathway; however approximately one in five TG acyl moieties predate nitrogen stress, indicating a significant input from membrane lipid acyl editing or direct trans-acylation reactions. 3) Equivalent intrinsic rates of efflux of entire lipids, including glycerol moieties, are apparent for both plastid and non-plastid membrane lipid classes. 4) Phospholipid and not galactolipid acyl chains are subject to efflux via acyl editing at an approximate rate of one for every two removed by catabolism. 5) The rate of incorporation of de novo synthesized fatty acids more than doubles in the first 2 days of nitrogen stress, with the majority entering membrane lipids; however TG incorporation is greater than any one specific lipid class. 6) Finally, the rate of FA incorporation into TG peaks after membrane incorporation rates decline, indicating competition between lipid classes as sinks for newly synthesized acyl chains.

TG Is Produced Mainly by the Sequential Acylation of Glycerol and Not by Membrane Lipid Remodeling Reactions

To address the contribution of complex lipid remodeling between membrane lipids and the expanding TG pool, we tracked stable isotopically labeled glycerol after 1 week of labeling with [U-13C]glucose followed by 1 week of label-free nitrogen stress. After 7 days in nitrogen stress, nearly half of the glycerol backbones in the membrane lipids were replaced, whereas the overall quantities remained constant, suggesting an efflux of esterified lipids and replacement by new synthesis. Only 8% of the stress-induced TG synthesized contained labeled glycerol, which was from the membrane lipid pool, demonstrating that 92% of the glycerol in the expanding TG pool was from new synthesis. Importantly, these data indicate that the enzymes governing the conversion of membrane lipids to TG, such as head group removal to generate DAG, which is subsequently converted to TG, do not play a major role in lipid droplet development during nitrogen stress. The 13CO2 labeling experiments demonstrated that ∼20% of the acyl chains of stress-induced TG synthesis were derived from membrane lipids, which coincides with the finding that 78% of the acyl chains labeled with [U-13C]glucose in the membrane lipids before nitrogen stress were trafficked into the expanding TG pool. The trafficking of labeled acyl chains from the PL is higher than can be accounted for by efflux of whole lipids, whereas in the GL, it is approximately equal.

Membrane Lipid Fatty Acid Moieties Are Incorporated into TG

Membrane lipid acyl chain flux is currently poorly defined both spatially and temporally, yet relies on distinct enzymatic reactions that collectively provide flexibility in lipid metabolic homeostasis (43–46). The insertion and removal of fatty acids that differ by chain length and number of double bonds defines membrane responses to temperature, salinity, and a variety of other abiotic conditions (47, 48). In our previous work, we showed that the rate of unsaturated FA accumulation in the TG pool is proportional with TG accumulation in C. subellipsoidea over 10 days of nitrogen stress (34). The flux of PUFA into TG during deuterium labeling was evident in the current study, where there were gradual increases of di- and tri-unsaturated acyl chains in the expanding TG pool. Although not strictly proven in algae, in other photosynthetic organisms polyunsaturated FA come from membrane lipids (45, 49, 50). It is possible the incorporation of two or three double bonds occurs coincident with FA synthesis or in the fully formed TG, but no such desaturase has been identified (51). The continual flux of PUFA into the TG pool therefore most likely reflects the rate of acyl chain transfer from membrane lipids. During deuterium labeling, the TG containing labeled PUFA was consistently 30–35% lower than in membrane lipids, whereas the GL and PL pools were essentially identical, which supports the conclusion that PUFA in TG come from the membrane lipids in C. subellipsoidea. This is the first study that demonstrates the transfer of intact acyl chains from membrane lipids into the TG pool in algae, specifically shown by tracking unlabeled FA (prior to nitrogen starvation) and labeled FA both before and during nitrogen stress.

Membrane Lipids Are an Early Sink for Increasing FA Synthesis Induced by Nitrogen Stress

Changes in fatty acid synthesis during nitrogen stress followed a two-stage process with an initial 2.5-fold increase followed by a slow and linear decline. Our findings showing this early increase in FA synthesis are in disagreement with the generally accepted hypothesis that the time lag between the onset of nitrogen stress and TG accumulation is related to the partitioning of carbon between carbohydrate and lipid synthesis (52, 53). Approximately two-thirds of the lipidome-wide influx of newly synthesized FA moieties entered the membrane lipids in the first 2 days of nitrogen stress. The fine scale analysis of acyl chain incorporation into specific lipid classes revealed that this influx was spread across all membrane lipids, but only DGDG had a similar influx to TG after 2 days of nitrogen stress. This influx into DGDG could explain the disparity between MGDG and DGDG degradation demonstrated previously (34). The incorporation rates of the newly synthesized FA into TG were shifted in time, peaking at 6 days of nitrogen stress, which was coincident with a sharp decline in the accumulation of newly synthesized acyl chains into membrane lipids. The time lag between the onset of nitrogen stress and the flux of acyl chains from membrane lipids into the TG pool likely reflects the up-regulation of several phospholipases (54) and the down-regulation of membrane lipid synthetic genes predicted from transcriptomic studies comparing normal growth with nitrogen stress conditions (55, 56).

Conclusions

Collectively, these data provide important mechanistic insights that show acyl chains are removed from PL through two distinct mechanisms, the first via the catabolism of glycerol and the second through specific acyl chain remodeling. Acyl chain remodeling in the PL through an intermediate lyso-lipid, requires acyl editing mechanisms that include PDAT, the Lands cycle, and LPCAT (8–10). Our findings measuring the quantity of intact pre-stressed acyl chains in the TG pool and the quantity of TG synthesized using glycerol by sequential acylation reactions and showing the efficient removal of acyl chains from the PL pool demonstrate that acyl editing is a major source of acyl chains during stress-induced TG synthesis. By comparison, and also in contrast, the predominant pathway involved in the trafficking of acyl chains from the GL is accompanied by the degradation of the lipid in entirety. The recently characterized plant galactolipid galactosyltransferase SFR2 (sensitive to freezing 2) mediates the transfer of the galactose head group from one MGDG to another, to form DAG and DGDG (57, 58). GLs, especially MGDG, are prone to degradation in algae during nitrogen stress coincident with a reduction in chloroplast size and photosynthetic capacity (59, 60). Although C. subellipsoidea contains an SFR2 homolog and offers a plausible pathway for converting MGDG to TG, our labeling data show that this cannot be the case. As noted above, nearly all of the newly synthesized TG contain newly synthesized glycerol, whereas 20% of the acyl chains arise from the membrane lipid pool. There was acyl chain transfer from the GL pool but no evidence of this proceeding through DAG. The PGD1 (plastid galactoglycerolipid degradation 1) lipase, initially defined in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, may contribute to TG synthesis through the hydrolysis of the acyl chain at the sn-1 position of glycerol in MGDG. However, the origins of the acyl chains in the expanding TG pools of C. reinhardtii likely differs significantly from C. subellipsoidea, as the amount of C16 FA in the sn-2 position of the two species is ∼80 and 10%, respectively (34, 35). Our data demonstrate only a minor amount of acyl chain editing of the GLs in C. subellipsoidea. An uncharacterized mechanism is apparently active during nitrogen stress in C. subellipsoidea, resulting in the transfer of acyl chains from membrane lipids coupled with the catabolism of the glycerol backbone rather than via acyl editing steps or lipid remodeling. Membrane lipids, including chloroplast-specific lipids, are instead continually synthesized and degraded during nitrogen starvation, leading to a general flux of acyl chains through membranes to the TG. Because very little to no lipid head group remodeling was detected in this study, we believe that a viable strategy for enhancing lipid accumulation through genetic engineering may involve the introduction of reactions leading to DAG production from other complex lipids.

Experimental Procedures

Growth Conditions and Stable Isotopic Labeling

General Growth Conditions

C. subellipsoidea C169 was originally obtained from Dr. James VanEtten (University of Nebraska) and grown in Bold's basal medium either containing (BBM) or not containing a nitrogen source of 2 mm sodium nitrate (N-BBM). Batch cultures were grown under photoautotrophic conditions in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks and 30 ml of culture volume or otherwise varied volumes depending on the experimental parameters elaborated below. Cultures were shaken at 120 rpm and maintained at 25 °C and 60 μmol of photons m−2s−1 of light using a New Brunswick Innova 43 shaker. Transitioning the algae from BBM to N-BBM involved centrifugation at 2500 × g for 5 min followed by removal of the BBM, a wash step in N-BBM to fully remove the nitrogen source, and finally suspending the washed cells in fresh, autoclave-sterilized N-BBM. Bioreactor-based experiments utilized a water-jacketed 3-liter glass bioreactor (Applikon Biotechnology) under photoautotrophic conditions (200 μmol of photons m−2s−1) while bubbling with compressed air (330 ppm CO2 in 3 liters min−1). The temperature (25 °C) and pH (6.6) were maintained using a circulating water bath and a set of peristaltic pumps that automatically adjusted the pH with 0.1 m KOH and 0.1 m HCl solutions based on continual input from a submerged pH probe. Initially 200 ml of inoculum was grown for 1 week in 250-ml shake flask cultures and then transferred to 1.8 liters of autoclave-sterilized BBM and grown for 1 week before transferring the biomass to 2 liters of N-BBM.

Conditions of [13C]Glucose Labeling

Algal cultures were 13C-labeled with [U-13C]glucose in BBM for 1 week and then starved of nitrogen in the absence of label for 1 week to analyze the transfer of pre-stress glycerol and acyl groups into the TG pool during lipid body development. Three cultures were initiated at 3 × 105 cells ml−1 in 30 ml of BBM media and immediately provided 25 mm [U-13C]glucose by drop filtration. After 1 week, the cultures were split in half, and one-half was collected by centrifugation and pellets stored immediately at −80 °C. The remaining cultures were washed free of nitrogen and label by centrifugation, and the supernatant was removed and replaced with sterilized N-BBM, with this step repeated twice. The cultures were resuspended in 30 ml of N-BBM, incubated in a lighted shaking incubator as already described for 1 week, and then collected by centrifugation and stored at −80 °C. Samples were lyophilized and dry weights measured prior to extraction as described below.

Conditions of D2O Labeling

Batch cultures were grown to early stationary phase, and three cultures per time point were transferred to N-BBM as described under “General Growth Conditions” above, with the exception that the N-BBM experimental medium was 30% by volume D2O (Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were placed in a shaking lighted incubator and collected every 2 days for a total of 8 days. A bioreactor culture was set up in 30% by volume D2O N-BBM as described under “General Growth Conditions.” 150-ml samples were removed daily and split into three technical replicate samples of 50 ml each. All samples were stored at −80 °C until they were lyophilized and weighed.

Conditions of [13C]O2 Labeling

The method of NaH13CO3 labeling was adopted from Burrows et al. (61). Cultures were first grown in 100 ml of BBM for 10 days in an Innova shaking incubator and transferred to N-BBM as described under “General Growth Conditions.” These cultures were added to clean, sterilized, 250-ml flasks and sparged with 0.22 μm of filtered N2 gas for 10 min to remove 12CO2. A final concentration of 25 mm NaH13CO3 was added to each flask, and they were sealed with silicone stoppers to prevent gas exchange during the labeling period of 1 week. A parallel study was conducted using unlabeled NaHCO3 to assess the quantity of TG molecular species. Samples were taken immediately and at 1, 3, and 7 days after the transfer to 13C-labeled N-BBM (three cultures per time point). Samples were frozen and maintained at −80 °C until lyophilized and weighed prior to lipid extraction and lipid class separations as detailed below.

Analysis Methods

Lipid Extraction and Separation

Lipid extraction and separation methods were standardized for all experiments. Extractions were performed on lyophilized and weighed samples of algae using a modified version of the Bligh and Dyer method (62). C. subellipsoidea cell walls were disrupted prior to solvent extraction, performed using 0.7-mm zirconia beads and a Qiagen TissueLyser LT bead mill (50 Hz for 5 min). Extraction solvent (100 μl, methanol/chloroform (2:1) containing 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene) was added with the necessary internal standards prior to milling. The disrupted samples were transferred to polytetrafluoroethylene-lined glass vials with 3 ml of the extraction solvent and shaken using a vortex mixer for 1 h. One ml of chloroform and 2 ml of 0.08% aqueous potassium chloride were added and the lipids partitioned by centrifugation (2,520 × g for 5 min). The organic layer was transferred to a fresh vial, and the sample was dried at 40 °C under N2 gas.

To separate neutral lipids, the crude lipid extracts were resuspended in 1 ml of methylene chloride and applied to a pre-equilibrated column containing 400 mg of 200–450-mesh 60 Å silica gel (Sigma-Aldrich). The neutral lipids were eluted with 2 ml of methylene chloride. To separate the membrane lipids, the crude lipid extracts were resuspended in 1 ml of acetone/methanol (9:1) and applied to a pre-equilibrated column containing 400 mg of 200–450-mesh 60 Å silica gel. The galactolipids were eluted using 2 ml of the same solvent, and the PL were then eluted with 3 ml of methanol. The different lipid fractions were dried under an N2 stream at 40 °C. The efficiency of lipid fractionation was routinely monitored using thin layer chromatography.

Fatty Acid Analysis Using GC-MS

Fatty acids were analyzed as methyl esters (FAME) synthesized from the dried lipid extracts or directly from TLC scrapings and dried in fresh glass vials at 45 °C under N2 gas as detailed previously (34). Hexanes (200 μl) were added to the dried FAME and mixed thoroughly, and 100 μl was transferred to GC vials containing 500-μl inserts. The samples were analyzed using a SelectFAME column (Agilent Technologies; 200 m × 271 μm × 0.25 μm) on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph equipped with a 5975C VL MS triple axis detector. The initial oven temperature at 130 °C was held for 10 min and successively ramped by 10 °C per min to 160, 190, 220, and 250 °C incorporating holds of 7, 7, 22, and 17 min, respectively. The pressure and inlet temperatures were constant at 62.3 psi and 250 °C. The FAME peaks corresponding to different fatty acids were identified by comparing the fragmentation patterns with a standard National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database and verified using a commercial standard mixture (37 FAME standard, Fisher Scientific). Quantification was accomplished using known amounts of internal standards.

Glycerol Analysis Using GC-MS

Esterified glycerol moieties were hydrolyzed from complex lipids during the initial saponification step of the FAME synthesis method detailed above. The aqueous phase samples from the solvent-partitioning step after FAME synthesis were collected and evaporated to dryness under N2 gas at 45 °C to isolate glycerol. The dried aqueous phase samples were lyophilized overnight prior to derivatization. Stable isotopic labeling in the glycerol moiety of the TG, GL, and PL pools was then determined using a GC-MS method developed by Shen and Xu (63). Glycerol samples were derivatized in sealed glass vials with 200 μl of trimethylsilylimidazole (Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 μl of acetonitrile for 45 min at 60 °C. The samples were then dried under N2 at room temperature, suspended in 100 μl of hexane, transferred to fresh vials, and separated in a 30-m Agilent DB 5-ms capillary column on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph equipped with a 5975C VL MS triple axis detector. 5 μl of each sample was injected with a 2:1 split flow of 6 ml per min with a run time of 16 min, an inlet temperature of 280 °C, and pressure set to 30 psi. The initial oven temperature of 100 °C was held for 3 min followed by a 50 °C per min ramp to 250 °C held for 10 min. The column flow was held constant at 3 ml min−1. Percentage labeling was determined from MS scans averaged across the resulting total ion chromatographic peaks by comparison of the isotopic distributions of molecular ion signal intensities to unlabeled glycerol. The m/z 293 ion used for 13C labeling analysis is 15 atomic mass units less than the intact molecular ion attributed to the loss of a methyl group from a trimethylsilylimidazole moiety by comparative analysis of the theoretical and experimental isotopic distribution patterns of unlabeled glycerol.

Lipid Quantification and Analysis Using LC-MS/MS

A SCIEX Q-Trap 4000 LC-MS/MS with a Shimadzu UFLC-XR system was used to quantify the GL, PL, and TG pools after growth following isotopic labeling experiments as detailed above. An Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-18 4.6 × 50 mm (2.7 μm) column and an Agilent Eclipse Plus-C18 narrow-bore 2.1 × 12.5 mm (5μ) guard column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) were used to quantify mono-, di-, and trigalactosyl-diacylglycerides and phosphatidylcholines as described previously (24). Neutral lipids were separated from total lipid extracts to reduce the possibility of spectral contamination by non-TG lipids. Catalytic saturation of the TG pool using platinum (IV) oxide and H2 gas was also done as described previously (35), coalescing TG molecular species with equivalent FA chain lengths but varied unsaturation and removing confounding monoisotopic mass peaks. A binary solvent system consisting of methanol/1.6 mm ammonium formate/0.7 mm formic acid (solvent A) and chloroform (solvent B), and an Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-8 4.6 × 50 mm (2.7 μm) column equipped with a 4.6 × 5 mm (2.7 μm) guard column of the same type provided chromatographic separation. Solvent B was held for 1 min at 7%, increased to 25% over 2 min, 30% in 4 min, and then 7% in 1 min, and held 2 min further. The column temperature was held constant at 40 °C. The MS settings and multiple reaction monitoring used were the same as reported previously (35). Multiple reaction monitoring spectra were used to quantify the TG for the continuous batch culture deuterium labeling experiment; the TG were run first to confirm the spectral windows and then used to inform Q1 MS analyses of isotopic distributions for the measurement of 13C incorporation from 13CO2.

FA Synthesis and Acyl Chain Incorporation into Different Lipid Pools

Algae of various classes have been long known to tolerate D2O even at concentrations reaching 100% (64), and its use in measuring FA synthesis rates in other organisms is established (65). The transfer of the label into FA was tracked over time, the results graphed, and the synthesis rate measured as the slope of the resulting least squares fitted line. Rate measurements were conducted by analyzing deuterium labeling in fatty acids converted to FAME using GC-MS after 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h of incubation with 20% D2O. Rates were measured in TG, GL, and PL pools of algae undergoing a time course of nitrogen starvation and repletion to study the changes in FA synthesis and allocation during lipid droplet production and catabolism. Cultures (n = 4) were nitrogen-starved for a total of 14 days, at which point sodium nitrate (2 mm) was added to initiate recovery from nitrogen stress. Rates were measured at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, and 14 days of growth in N-BBM followed by 1, 2, and 4 days after nitrogen readdition. Four 750-ml batch cultures constituting biological repeats were initially grown for 2 weeks in BBM to produce cell biomass for the experiment. These were centrifuged, and the pellets were washed and resuspended into four sets of 10 120-ml N-BBM cultures housed in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks kept sterile using plugs with inset 2-μm pore size filters (Whatman Bugstopper venting closures). Because of the poor surface to volume ratio, the cultures were supplemented with 2.2 mg (218 μm) of NaHCO3 supplied once/day. The cultures were kept in an Innova shaking incubator (New Brunswick) at 120 rpm, 25 °C, and 60 μmol of photons m−2s−1; OD measurements were taken daily at 550 nm. Rate time courses were initiated by removing four biological replicate cultures from the nitrogen starvation/repletion time course, transferring 20 ml from each into four sterilized 250-ml flasks containing 5 ml of D2O (99%, Sigma-Aldrich) in each, and collecting 20 ml at the zero time point. These flasks were placed back into the original shaking incubator through the labeling time course. Four biological replicates were removed at specified time points, collected by centrifugation, and the pellets frozen in liquid N2. Samples were lyophilized overnight at the conclusion of each rate time course. Lipid extractions, separations of lipid classes, conversion to FAME, and GC-MS analysis were done using techniques already described.

Statistical Analysis

The data presented are from experiments done 3–4 times (biological replicates) as indicated, and values are shown ± S.D. ANOVA was used for pairwise comparisons.

Author Contributions

J. W. A. and P. N. B. developed the conceptual basis of the study. J. W. A. completed the experiments detailed in the study. J. W. A., P. N. B., and C. C. D. analyzed the data. J. W. A., C. C. D., and P. N. B. wrote and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We thank Drs. Paul Blum and Rahul Tevatia for bioreactor use and assistance.

This work was supported by Grants EPS-1004094 (to P. N. B. and C. C. D.) and 1264409 (to C. C. D.) from the National Science Foundation and by a grant from the Nebraska Center for Energy Sciences Research (to P. N. B.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- TG

- triglyceride

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- PG

- phsophatidylglycerol

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- FA

- fatty acid(s)

- LPCAT

- lyso-phosphatidylcholine acyltransferase

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- PDAT

- phosphatidylcholine:diacylglycerol transacylase

- PDCT

- phosphatidylcholine:diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase

- MGDG

- monogalactosyldiacylglycerol

- DGDG

- digalactosyldiacylglycerol

- TGDG

- trigalactosyldiacylglycerol

- GL

- galactolipid

- PL

- phospholipid

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- FAME

- fatty acid methyl ester(s)

- DW

- dry weight.

References

- 1. Georgianna D. R., and Mayfield S. P. (2012) Exploiting diversity and synthetic biology for the production of algal biofuels. Nature 488, 329–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tevatia R., Allen J., Blum P., Demirel Y., and Black P. (2014) Modeling of rhythmic behavior in neutral lipid production due to continuous supply of limited nitrogen: mutual growth and lipid accumulation in microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 170, 152–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chisti Y., and Yan J. Y. (2011) Energy from algae: current status and future trends. Algal biofuels: a status report. Appl. Energy 88, 3277–3279 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huppe H. C., Farr T. J., and Turpin D. H. (1994) Coordination of chloroplastic metabolism in N-limited Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by redox modilation 2: redox modulation activates the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway during photosynthetic nitrate assimilation Plant Physiol. 105, 1043–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chisti Y. (2013) Constraints to commercialization of algal fuels. J. Biotechnol. 167, 201–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Upchurch R. G. (2008) Fatty acid unsaturation, mobilization, and regulation in the response of plants to stress. Biotechnol. Lett. 30, 967–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tjellström H., Zhen L. Y., Allen D. K., and Ohlrogge J. B. (2012) Rapid kinetic labeling of Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures: implications for models of lipid export from plastids. Plant Physiol. 158, 601–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lands W. E. (1958) Metabolism of glycerolipids: comparison of lecithin and triglyceride synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 231, 883–888 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoon K., Han D., Li Y., Sommerfeld M., and Hu Q. (2012) Phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase is a multifunctional enzyme involved in membrane lipid turnover and degradation while synthesizing triacylglycerol in the unicellular green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 24, 3708–3724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yurchenko O. P., Nykiforuk C. L., Moloney M. M., Ståhl U., Bana A., Stymne S., and Weselake R. J. (2009) A 10-kDa acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP) from Brassica napus enhances acyl exchange between acyl-CoA and phosphatidylcholine. Plant Biotechnol. J. 7, 602–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Essigmann B., Güler S., Narang R. A., Linke D., and Benning C. (1998) Phosphate availability affects the thylakoid lipid composition and the expression of SQD1, a gene required for sulfolipid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1950–1955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakamura Y., Awai K., Masuda T., Yoshioka Y., Takamiya K., and Ohta H. (2005) A novel phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase C induced by phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7469–7476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cruz-Ramirez A., Oropeza-Aburto A., Razo-Hernandez F., Ramirez-Chavez E., and Herrera-Estrella L. (2006) Phospholipase DZ2 plays an important role in extraplastidic galactolipid biosynthesis and phosphate recycling in Arabidopsis roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6765–6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang L., Shen W., Kazachkov M., Chen G., Chen Q., Carlsson A. S., Stymne S., Weselake R. J., and Zou J. (2012) Metabolic interactions between the Lands cycle and the Kennedy pathway of glycerolipid synthesis in Arabidopsis developing seeds. Plant Cell 24, 4652–4669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu Y., Chi X., Yang Q., Li Z., Liu S., Gan Q., and Qin S. (2009) Molecular cloning and stress-dependent expression of a gene encoding Delta(12)-fatty acid desaturase in the Antarctic microalga Chlorella vulgaris NJ-7. Extremophiles 13, 875–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hu Z., Ren Z., and Lu C. (2012) The phosphatidylcholine diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase is required for efficient hydroxy fatty acid accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158, 1944–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wickramarathna A. D., Siloto R. M., Mietkiewska E., Singer S. D., Pan X., and Weselake R. J. (2015) Heterologous expression of flax Phospholipid:diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase (PDCT) increases polyunsaturated fatty acid content in yeast and Arabidopsis seeds. BMC Biotechnol. 15, 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guarnieri M. T., Nag A., Smolinski S. L., Darzins A., Seibert M., and Pienkos P. T. (2011) Examination of triacylglycerol biosynthetic pathways via de novo transcriptomic and proteomic analyses in an unsequenced microalga. PLoS One 6, e25851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miller R., Wu G., Deshpande R. R., Vieler A., Gärtner K., Li X., Moellering E. R., Zäuner S., Cornish A. J., Liu B., Bullard B., Sears B. B., Kuo M. H., Hegg E. L., Shachar-Hill Y., Shiu S. H., and Benning C. (2010) Changes in transcript abundance in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii following nitrogen deprivation predict diversion of metabolism. Plant Physiol. 154, 1737–1752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lv H., Qu G., Qi X.., Lu L., Tian C., and Ma Y. (2013) Transcriptome analysis of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii during the process of lipid accumulation. Genomics 101, 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wase N., Black P. N., Stanley B. A., and DiRusso C. C. (2014) Integrated quantitative analysis of nitrogen stress response in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using metabolite and protein profiling. J. Proteome Res. 13, 1373–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Simionato D., Block M. A., La Rocca N., Jouhet J., Maréchal E., Finazzi G., and Morosinotto T. (2013) The response of Nannochloropsis gaditana to nitrogen starvation includes de novo biosynthesis of triacylglycerols, a decrease of chloroplast galactolipids, and reorganization of the photosynthetic apparatus. Eukaryot. Cell 12, 665–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li J., Han D., Wang D., Ning K., Jia J., Wei L., Jing X., Huang S., Chen J., Li Y., Hu Q., and Xu J. (2014) Choreography of transcriptomes and lipidomes of nannochloropsis reveals the mechanisms of oil synthesis in microalgae. Plant Cell 26, 1645–1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohlrogge J., and Browse J. (1995) Lipid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 7, 957–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li-Beisson Y., Beisson F., and Riekhof W. (2015) Metabolism of acyl-lipids in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 82, 504–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blanc G., Agarkova I., Grimwood J., Kuo A., Brueggeman A., Dunigan D. D., Gurnon J., Ladunga I., Lindquist E., Lucas S., Pangilinan J., Pröschold T., Salamov A., Schmutz J., Weeks D., et al. (2012) The genome of the polar eukaryotic microalga Coccomyxa subellipsoidea reveals traits of cold adaptation. Genome Biol. 13, R39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blanc G., Duncan G., Agarkova I., Borodovsky M., Gurnon J., Kuo A., Lindquist E., Lucas S., Pangilinan J., Polle J., Salamov A., Terry A., Yamada T., Dunigan D. D., Grigoriev I. V., et al. (2010) The Chlorella variabilis NC64A genome reveals adaptation to photosymbiosis, coevolution with viruses, and cryptic sex. Plant Cell 22, 2943–2955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wen Q., Chen Z., Li P., Han Y., Feng Y., and Ren N. (2013) Lipid production for biofuels from effluent-based culture by heterotrophic Chlorella protothecoides. Bioenergy Res. 6, 877–882 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tang H., Chen M., Garcia M. E., Abunasser N., Ng K. Y., and Salley S. O. (2011) Culture of microalgae Chlorella minutissima for biodiesel feedstock production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 108, 2280–2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chader S., Hacene H., and Agathos S. N. (2009) Study of hydrogen production by three strains of Chlorella isolated from the soil in the Algerian Sahara. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 34, 4941–4946 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee S. J., Go S., Jeong G. T., and Kim S. K. (2011) Oil production from five marine microalgae for the production of biodiesel. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 16, 561–566 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nicolo M. S., Columbro G., La Porta S., Cicero N., Dugo G. M., and Guglielmino S. P. P. (2010) High quality oil for biodiesel production and biomass yields from a microalga Coccomyxa sp by autotrophic growth. J. Biotechnol. 150, S163–S163 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ras M., Steyer J. P., and Bernard O. (2013) Temperature effect on microalgae: a crucial factor for outdoor production. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio-Technol. 12, 153–164 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Allen J. W., DiRusso C. C., and Black P. N. (2015) Triacylglycerol synthesis during nitrogen stress involves the prokaryotic lipid synthesis pathway and acyl chain remodeling in the microalgae Coccomyxa subellipsoidea. Algal Res. 10, 110–120 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allen J. W., DiRusso C. C., and Black P. N. (2014) Triglyceride quantification by catalytic saturation and LC-MS/MS reveals an evolutionary divergence in regioisometry among green microalgae. Algal Res. 5, 23–31 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Urzica E. I., Vieler A., Hong-Hermesdorf A., Page M. D., Casero D., Gallaher S. D., Kropat J., Pellegrini M., Benning C., and Merchant S. S. (2013) Remodeling of membrane lipids in iron-starved Chlamydomonas. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 30246–30258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Solovchenko A. E. (2013) Physiology and adaptive significance of secondary carotenogenesis in green microalgae. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 60, 1–13 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Solovchenko A. E. (2012) Physiological role of neutral lipid accumulation in eukaryotic microalgae under stresses. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 59, 167–176 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Demé B., Cataye C., Block M. A., Maréchal E., and Jouhet J. (2014) Contribution of galactoglycerolipids to the 3-dimensional architecture of thylakoids. FASEB J. 28, 3373–3383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pollard M., Delamarter D., Martin T. M., and Shachar-Hill Y. (2015) Lipid labeling from acetate or glycerol in cultured embryos of Camelina sativa seeds: a tale of two substrates. Phytochemistry 118, 192–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huard K., Londregan A. T., Tesz G., Bahnck K. B., Magee T. V., Hepworth D., Polivkova J., Coffey S. B., Pabst B. A., Gosset J. R., Nigam A., Kou K., Sun H., Lee K., Herr M., et al. (2015) Discovery of selective small molecule inhibitors of monoacylglycerol acyltransferase 3. J. Med. Chem. 58, 7164–7172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Juergens M. T., Deshpande R. R., Lucker B. F., Park J. J., Wang H., Gargouri M., Holguin F. O., Disbrow B., Schaub T., Skepper J. N., Kramer D. M., Gang D. R., Hicks L. M., and Shachar-Hill Y. (2015) The regulation of photosynthetic structure and function during nitrogen deprivation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 167, 558–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bates P. D., Fatihi A., Snapp A. R., Carlsson A. S., Browse J., and Lu C. (2012) Acyl editing and headgroup exchange are the major mechanisms that direct polyunsaturated fatty acid flux into triacylglycerols. Plant Physiol. 160, 1530–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bates P. D., Durrett T. P., Ohlrogge J. B., and Pollard M. (2009) Analysis of acyl fluxes through multiple pathways of triacylglycerol synthesis in developing soybean embryos. Plant Physiol. 150, 55–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Beisson F., Koo A. J., Ruuska S., Schwender J., Pollard M., Thelen J. J., Paddock T., Salas J. J., Savage L., Milcamps A., Mhaske V. B., Cho Y., and Ohlrogge J. B. (2003) Arabidopsis genes involved in acyl lipid metabolism: a 2003 census of the candidates, a study of the distribution of expressed sequence tags in organs, and a Web-based database. Plant Physiol. 132, 681–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stymne S., and Stobart A. K. (1984) Evidence for the Reversibility of the acyl-CoA-lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase in microsomal preparations from developing safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L) colyledons and rat liver. Biochem. J. 223, 305–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guerzoni M. E., Ferruzzi M., Sinigaglia M., and Criscuoli G. C. (1997) Increased cellular fatty acid desaturation as a possible key factor in thermotolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Can. J. Microbiol. 43, 569–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang M., Barg R., Yin M., Gueta-Dahan Y., Leikin-Frenkel A., Salts Y., Shabtai S., and Ben-Hayyim G. (2005) Modulated fatty acid desaturation via overexpression of two distinct omega-3 desaturases differentially alters tolerance to various abiotic stresses in transgenic tobacco cells and plants. Plant J. 44, 361–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Harwood J., and Moore T. S. (1989) Lipid metabolism in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 8, 1–43 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guschina I. A., and Harwood J. L. (2006) Lipids and lipid metabolism in eukaryotic algae. Prog. Lipid Res. 45, 160–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wallis J. G., and Browse J. (2002) Mutants of Arabidopsis reveal many roles for membrane lipids. Prog. Lipid Res. 41, 254–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ikaran Z., Suarez-Alvarez S., Urreta I., and Castanon S. (2015) The effect of nitrogen limitation on the physiology and metabolism of Chlorella vulgaris var L3. Algal Res. 10, 134–144 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang Z. T., Ullrich N., Joo S., Waffenschmidt S., and Goodenough U. (2009) Algal lipid bodies: stress induction, purification, and biochemical characterization in wild-type and starchless Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot. Cell 8, 1856–1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Alipanah L., Rohloff J., Winge P., Bones A. M., and Brembu T. (2015) Whole-cell response to nitrogen deprivation in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 6281–6296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schmollinger S., Mühlhaus T., Boyle N. R., Blaby I. K., Casero D., Mettler T., Moseley J. L., Kropat J., Sommer F., Strenkert D., Hemme D., Pellegrini M., Grossman A. R., Stitt M., Schroda M., and Merchant S. S. (2014) Nitrogen-sparing mechanisms in Chlamydomonas affect the transcriptome, the proteome, and photosynthetic metabolism. Plant Cell 26, 1410–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Boyle N. R., Page M. D., Liu B., Blaby I. K., Casero D., Kropat J., Cokus S. J., Hong-Hermesdorf A., Shaw J., Karpowicz S. J., Gallaher S. D., Johnson S., Benning C., Pellegrini M., Grossman A., and Merchant S. S. (2012) Three acyltransferases and nitrogen-responsive regulator are implicated in nitrogen starvation-induced triacylglycerol accumulation in Chlamydomonas. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15811–15825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Thorlby G., Fourrier N., and Warren G. (2004) The sensitive to freezing2 gene, required for freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana, encodes a β-glucosidase. Plant Cell 16, 2192–2203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Roston R. L., Wang K., Kuhn L. A., and Benning C. (2014) Structural determinants allowing transferase activity in SENSITIVE TO FREEZING 2, classified as a family I glycosyl hydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 26089–26106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Preininger É., Kósa A., Lőrincz Z. S., Nyitrai P., Simon J., Böddi B., Keresztes Á., and Gyurján I. (2015) Structural and functional changes in the photosynthetic apparatus of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii during nitrogen deprivation and replenishment. Photosynthetica 53, 369–377 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pancha I., Chokshi K., George B., Ghosh T., Paliwal C., Maurya R., and Mishra S. (2014) Nitrogen stress triggered biochemical and morphological changes in the microalgae Scenedesmus sp. CCNM 1077. Bioresour. Technol. 156, 146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Burrows E. H., Bennette N. B., Carrieri D., Dixon J. L., Brinker A., Frada M., Baldassano S. N., Falkowski P. G., and Dismukes G. C. (2012) Dynamics of lipid biosynthesis and redistribution in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum under nitrate deprivation. Bioenergy Res. 5, 876–885 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bligh E. G., and Dyer W. J. (1959) A rapid method for total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shen Y., and Xu Z. (2013) An improved GC-MS method in determining glycerol in different types of biological samples. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 930, 36–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chorney W., Scully N. J., Crespi H. L., and Katz J. J. (1960) The growth of algae in deuterium oxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 37, 280–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Patton G. M., and Lowenstein J. M. (1979) Measurement of fatty-acid synthesis by incorporation of deuterium from deuterated water. Biochemistry 18, 3186–3188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]