Abstract

Background

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental health concern due to its various negative consequences, especially in sexual function. Therefore, the treatment of sexual dysfunction in women with OCD is important in order to improve the patient’s marital function and mental health.

Objectives

To compare the sexual behavior and sexual and marital satisfaction in women with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) before and after treatment with fluoxetine and cognitive behavior therapy

Methods

This randomized clinical trial was conducted at psychiatric and psychological counseling centers in Kashan (Iran) from January 2, 2014, to December 29, 2014. Fifty-eight women with OCD were included in the study. In order to compare the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment (fluoxetine) and psychological treatment, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), 58 female patients with OCD (diagnosed based on DSM-IV-T criteria) were randomized equally to either fluoxetine (at a dose of 60–80 mg daily for 3 months) or CBT (10 45-minute sessions). OCD and sexual behavior status of the patients before and after the intervention was assessed with the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) and Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire, respectively. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. To compare changes between the two groups, an independent T-test was used. Finally, the effects of all potential factors on treatment outcome were analyzed using factorial ANCOVA.

Results

The mean score for OCD in the fluoxetine group was 25.6 ± 4.8 at the beginning of the experiment and 18.79 ± 4.26 at the end of the study, while in the CBT group it was 25.6 ± 4.8 and 18.79 ± 4.26, respectively. No significant differences were found between two groups regarding obsession score changes. These scores in fluoxetine group were 58.1 and 52.8, respectively (p=0.046). There was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of sexual performance (p=0.003).

Conclusion

In this study, our findings demonstrate a significant reduction in symptom severity of OCD after treatment with fluoxetine and CBT, indicating CBT can be an alternative for fluoxetine therapy in such patients. Therefore, both pharmacotherapy and CBT can be used for this purpose in clinical practices, but more studies are needed.

Clinical trial registration

The trial was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (http://www.irct.ir) with the Irct ID: IRCT2013091014619N1.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Keywords: Cognitive behavior therapy, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Fluoxetine, Sexual behavior

1. Introduction

Based on DSM IV-TR criteria, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is an anxiety disorder described by recurrent or unrelenting thoughts, impulses, or images that are experienced as disturbing or distressing (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) often performed in response to anxiety caused by an obsession (1). This disorder is a debilitating condition that causes low quality of life in many aspects, including sexual dysfunction (2–7). According to recent epidemiologic studies, the prevalence of OCD in the United States is estimated at approximately 2%–3% (2, 4). Currently, pharmacotherapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are considered effective treatments among adults and children, suggesting that CBT is associated with greater effects than SSRIs alone (4, 5). On the other hand, some studies have shown that treatment with SSRIs and CBT had a similar effect on mild to moderate symptoms of OCD (5, 6). In people over the age of 18, SSRIs (including Fluoxetine, Fluvoxamin, Paroxetine, and Sertraline) are used for treatment; in such cases, the required dose for the treatment is higher than the doses needed to treat depression (7). One of the common side effects of SSRIs is sexual dysfunction, which clinically can be manifested as delayed ejaculation in men, delayed orgasm or anorgasmia in women, and decreased libido (4). Their negative impact on a patient’s quality of life may lead to rejection of treatment by the patient (8) and subsequent relapse of the disease (9). Because one of the most important factors in marital happiness and good quality of life is sexual relationships and pleasure, an unsatisfactory sexual life can cause a feeling of deprivation, frustration, and lack of safety and eventually marital disruption and divorce (10). Considering the high prevalence of sexual and marital problems in patients with OCD and the side effects of pharmacotherapy with SSRIs as a single treatment for this disorder, the present study was designed to compare the effect of pharmacotherapy (fluoxetine) and CBT on OCD score and increasing sexual behavior in such patients.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Trial design

This prospective single blinded randomized trial was conducted in psychiatric and psychological counseling centers in Kashan (Iran) from January 2, 2014, to December 29, 2014.

2.2. Participants

After approving of the study by the Ethical Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences and obtaining informed consent from all the patients after a full explanation of the nature of the treatment trial, 58 female (18–52 y) outpatients with the diagnosis of OCD according to the DSM IV-TR were recruited through permuted block randomization in two equal groups to receive either fluoxetine or CBT.

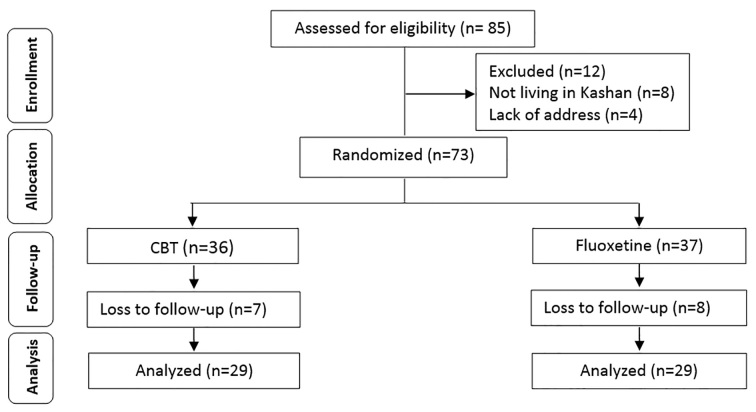

Sample size was calculated at 29 in each group based on the sexual dysfunction prevalence (50%–80%) in patients treated with SSRIs (13) and sexual dysfunction in OCD (26%) (8) and confidence interval of 95% and power of 90%. In Figure 1, a CONSORT diagram depicting the flow of study participants is shown.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram depicting flow of study participants

2.3. Selection criteria

For data collection, all married women who were diagnosed with OCD through clinical interview based on DSM IV-TR, referred to psychiatric and psychological counseling centers in Kashan during the study period, were considered. All cases that met the following criteria were excluded from the study: disorders of axis I and II comorbidity based on a clinical interview with the exception of sexual dysfunction, psychotic symptoms, a history of sexual dysfunction before the recent period of the disease, endocrine disorders (e.g., thyroid dysfunction and diabetes), localized genital problems (e.g., bacterial vaginosis and pelvic infections), hypogonadism, cardiovascular disease (e.g., angina pectoris, myocardial infarction), renal dysfunction, neurological disorders (e.g., stroke, spinal cord injuries, pelvic autonomic neuropathy), use of any psychiatric medication during the last month, history of previous abdominal or pelvic surgery, which caused sexual disturbances (e.g., Oophorectomy, uterus prolapsed surgery) and use of any other drugs that cause sexual dysfunction. If any patient in the last three months had each of the mentioned criteria, they have been excluded from the study.

2.4. Measuring tools

2.4.1. Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

This rating scale was designed in the late 1980s to rate the severity and type of symptoms in patients with OCD. In general, the items depend on the patient’s report; however, the final rating is based on the clinical judgment of the interviewer. Rate the characteristics of each item (64 items in total, including obsessions such as contamination, aggressive, sexual, religious, somatic, etc. and compulsions such as cleaning, checking, ordering, arranging, counting, etc.) during the prior week up until and including the time of the interview. Scores should reflect the average (mean) occurrence of each item for the entire week (PDF). A severity scale is a semistructured clinical scale with 10 questions to measure the presence and severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms during the prior week up until and including the time of the interview (11). A 10-item scale, each item rated from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (extreme symptoms), yields a total possible score range from 0 to 40. Scores for diagnosis of OCD typically are in the range of 16–30, and 16 is the appropriate threshold for drug therapy. Reported validity and internal consistency coefficient for this scale was 98% and 89%, respectively (12). In Iran, the reliability of the scale was reported 0.84 after test–re-test within two weeks (12).

2.4.2. Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire

This tool consists of 19 questions and was designed in 2000 by Rosen et al. (13). Mohammadi et al. in 2008 standardized the test and reliability for each of the six domains of the scale, and the whole test was calculated at 0.85 using Cronbach’s alpha (14). According to this scale, the higher scores indicate the better sexual function. The maximum score for each area is 6; for the total scale, the score is 36. Zero score indicates that the person had no sexual activity during the last four weeks. The cut-off point for the scale is 28, and for subscales, desire (3.3), sexual arousal (3.4), lubrication (3.4), orgasm (3.4), satisfaction (3.8), and pain (3.8).

2.5. Interventions

All patients referred to the outpatient psychiatric and psychological counseling centers at the Kashan (Iran) received a diagnostic medical intake procedure, in which psychiatric and medical history were examined. In the case OCD diagnosis is suspected, the intake procedure consisted of standardized diagnostic measures for OCD and other DSM-IV diagnoses. If OCD was confirmed, and all inclusion/exclusion criteria were met, the patient was requested to participate in the study. After giving informed consent, patients were recruited through permuted block randomization in either pharmacological treatment or the CBT group. The pharmacotherapy group was treated with fluoxetine capsules with a mean dose of 60 mg daily (prepared by Abidi company), and cases in the CBT group received 10 45-minute sessions weekly by an expert clinical psychologist. After 3 months of medical treatment and after a course of CBT, Y-BOCS and FSFI tests were repeated for both groups of the study, and the test results before and after the treatment were compared in both approaches.

2.6. Statistical methods

Data were analyzed using IBM© SPSS© Statistics version 22 (IBM© Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics was used to examine differences in demographic and OCD characteristics at baseline between the fluoxetine group and the CBT group. Paired T-test was used to compare the score of each group before and after the intervention. To compare changes between the two groups, an independent T-test was used. Finally, the effects of all potential factors on treatment outcome were analyzed using factorial ANCOVA. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 58 women with OCD were finally allocated in two groups of 29 in this trial. The mean ± S.D. age was 32.58 ± 5.74 years (range 21–46). There was no significant difference between the CBT and fluoxetine groups regarding age, age at marriage, education level, and profession (p>0.05). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study participants and between-group differences of variables. As can be seen in Table 2, obsession of aggression was observed in 55.2% of women in the CBT group and 62.1% in the fluoxetine group. However, no significant correlation was found between groups regarding the aggression. Apart from compulsion subscales of ordering, arranging, and sexuality, no significant differences were found between the two groups in other subscales of OCD.

Table 1.

Demographics characteristics of participants in CBT and fluoxetine groups

| Variables | CBT; n (%) | Fluoxetine; n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ≤34 | 17 (58.6) | 16 (65.5) | 0.588 |

| ≥35 | 12 (41.4) | 13 (44.8) | ||

| Education | Primary school | 2 (6.9) | 7 (24.1) | 0.09 |

| Junior high school | 1 (3.4) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| Senior high school | 9 (31) | 8 (27.6) | ||

| Higher education | 17 (58.6) | 10 (34.5) | ||

| Age at marriage (year) | ≤9 | 12(41.4) | 12 (41.4) | 0.074 |

| 10–14 | 15 (51.7) | 15 (51.7) | ||

| ≥15 | 2 ( 6.9) | 2 (6.9) | ||

| Occupation | Housekeeper | 23 ( 73.9) | 28 (96.6) | 0.052 |

| Sedentary work | 5 (17.2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Student | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) | ||

Table 2.

Frequency of different type of OCD before intervention in two groups of treatment

| Type of OCD | CBT; n (%) | Fluoxetine; n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obsession | Aggression | 16 (55.2) | 18 (62.1) | 0.79 |

| Contamination | 29 (100) | 26 (89.7) | 0.237 | |

| Sexual | 6 (20.7) | 0 (0) | 0.023 | |

| Hoarding | 0 (0) | 4 (13.8) | 0.112 | |

| Religious | 8 (27.6) | 4 (13.8) | 0.331 | |

| Symmetry | 5 (17.2) | 6 (20.7) | 0.738 | |

| Somatic | 6 (20.7) | 12 (41.4) | 0.155 | |

| Miscellaneous | 15 (51.7) | 16 (55.2) | 0.792 | |

| Compulsion | Cleaning | 29 (100) | 20 (69) | N.S* |

| Checking | 24 (82.8) | 20 (69) | 0.358 | |

| Ordering & arranging | 3 (10.3) | 6 (20.7) | 0.47 | |

| Counting | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) | 0.112 | |

| Symmetry | 4 (13.8) | 13 (44.8) | 0.02 | |

| Hoarding | 4 (13.8) | 3 (10.3) | N.S* | |

| Miscellaneous | 11 (37.9) | 17 (5.6) | 0.189 | |

NS: Non-significant

Table 3 compares the obtained results from analysis of intervention in terms of obsession severity status. As shown, there was no significant difference between two groups of the study regarding the number of cases with the severe obsession and mean score of OCD prior to commencing of the treatment (p>0.05). It is apparent from this table that, in both groups of the study, a statistically significant reduction in obsession score was found after treatment (p<0.001) (Table 3). In addition, covariance analysis revealed that there was no difference between treatment groups regarding reduced obsession scores (p=0.156), and the only factor affecting the obsession score has been the previous OCD score of the subjects (p=0.001). In terms of pre-intervention sexual function score, no significant differences were found between two groups of study regarding mean FSFI score (p=0.187) (Table 4). It can be seen from the data in Table 4 that the mean score of desire before and after intervention was significant in CBT (p=0.039) but not in fluoxetine group (p=0.35). Also it can be seen that desire score has changed significantly before and after treatment in both groups of the study (p=0.028). In addition, no statistically significant difference was found regarding mean satisfaction score before and after intervention in CBT group (p=0.076) but significant difference (p=0.008) in the fluoxetine group. Moreover, what is interesting in the data of Table 4 is that, after intervention, satisfaction score in the CBT group was increased, while this score was decreased in the fluoxetine group. The difference between satisfaction and orgasm score changes in both groups after the intervention was statistically significant (p<0.05). Covariance analysis to adjust the effects of sexual function score, age, and marriage duration showed that FSFI score changes were not significantly affected by the treatment groups (p=0.001) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Frequency of obsession status of subjects before and after intervention

| Treatment groups | Obsession status | Before intervention; n (%) | After intervention; n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | Not | 0 (0) | 5 (17.2) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 0 (0) | 10 (34.5) | ||

| Moderate | 13 (44.8) | 10 (34.5) | ||

| Severe | 16 (55.2) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| Mean ± S.D. | 25.48±4.2 | 16.7±6.63 | ||

| Fluoxetine | Not | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 0 (0) | 7 (24.1) | ||

| Moderate | 15 (51.7) | 19 (65.5) | ||

| Severe | 14 (48.3) | 3 (10.3) | ||

| Mean ± S.D. | 25.65±4.8 | 18.79±4.26 |

Table 4.

Mean and standard deviation of subscales of the sexual function in both groups of the study before and after the intervention based on FSFI

| Sexual function subscales | CBT | Fluoxetine | p-value (Between groups) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | After intervention | p-value | Before intervention | After intervention | p-value | ||

| Desire | 5.41 (1.2) | 6.06 (1.38) | 0.039 | 5.2 (0.97) | 4.96 (1.29) | 0.354 | 0.028 |

| Arousal | 11.62 (0.76) | 13.65 (3.93) | >0.01 | 10.79 (0.59) | 10.17 (3.05) | 0.443 | 0.006 |

| Lubrication | 13.82 (0.85) | 14.27 (3.98) | 0.449 | 11.75 (0.48) | 11.51 (2.92) | 0.707 | 0.428 |

| Orgasm | 10.37 (0.6) | 11.10 (3.05) | 0.008 | 8.82 (0.39) | 7.86 (3.23) | 0.095 | 0.009 |

| Satisfaction | 10.65 (0.69) | 11.62 (3.61) | 0.076 | 10.31 (0.47) | 6.68 (3) | 0.008 | 0.002 |

| Pain | 11.27 (0.71) | 11.34 (3.74) | 0.858 | 11.7 (0.47) | 9.62 (3.58) | 0.121 | 0.129 |

| FSFI | 63.17 (3.45) | 63.06 (17.58) | 0.024 | 58.06 (1.59) | 52.82 (12.35) | 0.046 | 0.003 |

4. Discussion

This study investigated sexual function of women with OCD enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing fluoxetine and CBT. In this sample, our findings demonstrate a significant reduction in symptom severity of OCD after treatment with fluoxetine and CBT, indicating that CBT can be an alternative for fluoxetine therapy in such patients. In the fluoxetine group regarding sexual function, although there was no significant reduction in terms of arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and pain after treatment, but in the satisfaction area and sexual function, in general, a significant decrease was observed. In the CBT group, the sexual function of the patients in the phases of sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm was statistically significant improved. However, in terms of lubrication, pain, and satisfaction, despite the better scores, the changes were not statistically significant. In general, therefore, it seems that sexual function after treatment of OCD in the CBT group was more significantly improved than in the fluoxetine group; overall, sexual function has worsened in the later one. Medication usually is an effective treatment for OCD. About 7 out of 10 people with OCD will benefit from either medication or CBT. For those who benefit from medication, they usually see their OCD symptoms reduced by 40%–60%. SSRIs, which are traditionally used as antidepressants, also help to address OCD symptoms. For SSRIs to work, they must be taken regularly, but about half of the OCD patients stop taking their medication due to side effects or for other reasons (15). One of the most important reasons for discontinuing these drugs is sexual dysfunctional caused by these medications (16). Few studies were evaluated of sexual dysfunction associated with drug treatment in OCD (17, 18); however, a series of studies have described the effects of antidepressants on sexual health (19–23). Sexual dysfunction as a side effect of SSRI treatment is common and is typically seen in one-third of patients. Among the sexual side effects most commonly associated with SSRIs are delayed ejaculation and absent or delayed orgasm. Sexual desire (libido) and arousal difficulties are also frequently reported (24). Animal studies of the impact of serotonin agonist and antagonist agents on mounting and ejaculation have reported inconsistent results. Differential roles of different 5-HT receptor activation on sexual behavior may explain some of these inconsistencies (25). Most evidence indicates that 5-HT1A receptor agonists inhibit sexual behavior, while 5-HT2 or 5-HT3 receptors may exert a positive influence (26). One of the assumed hypotheses for SSRI-induced loss of sexual desire is the role of the 5-HT1A receptor-mediated norepinephrine neurotransmission. Because the sympathetic nervous system is supposed to be involved in sexual arousal in women, a small study analyzed the effect of sympathetic activation on SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Women who received Paroxetine and Sertraline, which are both highly selective for 5-HT1A, showed improvement in sexual arousal and orgasm after taking ephedrine before sexual activity. Women who took fluoxetine, which is less selective for 5-HT1A, show no change or decreased sexual function (27). The present findings seem to be consistent with above-mentioned studies and suggest that fluoxetine has an important role in worsening of sexual function, especially in the subscale of satisfaction in women with OCD. The incidence of sexual dysfunction related to SSRIs also can be difficult to determine because some sexual dysfunction often accompanies a primary psychiatric disorder or physical illness (25). The incidence of SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction was reported 30% to 50% by Balon (28), although others have reported higher incidences up to 80% (19), which is in agreement with the results of the current study. Few studies can be found in the literature attempting to measure the quality of sexually function of OCD patients after pure psychological treatment such as CBT. Franklin ME et al. (2002) during a clinical trial compared the effectiveness of CBT versus CBT plus SSRI in OCD treatment. In a clinical sample of 56 outpatients, 31 cases (55%) received CBT alone, and 25 (45%) received CBT plus SSRI. Both groups made clinically significant and comparable post-treatment gains, suggesting that CBT is effective with or without concomitant pharmacotherapy. Despite the different study design, the common feature of our study and Franklin’s one is effectiveness of CBT alone on OCD treatment (29). Several studies have been conducted on sexual function in women with anxiety disorders, including OCD, and, despite comparable results, different and sometimes conflicting results were met (30–34). For example, Vulink NC et al. (2006) during their study on sexual pleasure in women with OCD, revealed that female subjects with OCD had low sexual pleasure, high sexual revulsion, and decreased sexual functioning, which are not only attributed to medication or contamination obsessions (30). It can be inferred from some studies that decreased libido and sexual dysfunction are part of OCD characteristics (30, 31, 35, 36), and, due to the potentially confounding effects of the illness itself, it is difficult to attribute loss of sexual desire directly to SSRIs (37). Nevertheless, SSRIs are associated with risk of clinically significant sexual dysfunction (25). None of the above studies evaluate sexual satisfaction and sexual function after intervention, and data were found in literature reviews comparing OCD treatment with psychotropic medications and CBT; thus the design has been applied in the present study. Fear of contamination from sexual activity in most of the above-mentioned studies has been reported as an important factor for sexual dysfunction in OCD patients. However, in our study, despite the fact that all participants who have contamination obsession have suffered from compulsive washing; after CBT intervention, although the phases of lubrication and pain were improved, the change was not significant. Nevertheless, sexual desire, sexual arousal, and orgasm were improved significantly. Generally, it can be concluded that the changes in cognitive errors in terms of contamination and, on the other hand, behavioral therapy could improve the first phases: increasing sexual desire, sexual arousal, and leading orgasm in such cases, while no optimum vaginal lubrication is produced, and no sexual intercourse pain relief is followed. Limitations of our study were loss to follow-up in the fluoxetine group, which was high; this problem was solved by continuing upsampling to achieving results. Second, the taboo of talking about the issues about sexual problems was a major concern, and we tried to overcome this by talking with patients.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings showed a significant reduction in symptom severity of OCD after treatment with fluoxetine and CBT, indicating that CBT can be an alternative for fluoxetine therapy in such patients. Therefore, both pharmacotherapy and CBT can be used for this purpose in clinical practices, but more studies are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was the postgraduate thesis of the first author, Dr. Zahra Sabetnejad, for psychiatry specialty, which was supported by Kashan University of Medical Science, school of medicine, Kashan, Iran. The authors thank the patients, their families, and the personnel of psychiatric and psychological counseling centers in Kashan and Dr. Akbari for help with statistical analyses and planning the logistics of the research.

Footnotes

iThenticate screening: July 28, 2016, English editing: September 20, 2016, Quality control: October 25, 2016

Clinical trial registration:

The trial was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (http://www.irct.ir) with the Irct ID: IRCT2013091014619N1.

Funding:

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest:

There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Authors’ contributions:

All authors contributed to this project and article equally. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olatunji BO, Davis ML, Powers MB, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendurkar A, Kaur B. Major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder: do the sexual dysfunctions differ? Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(4):299–305. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadock BJ, Sadock V, Ruiz P. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 9th. Philadelphia: Volkmar, Klin, Robert, Schultz & Mathew; 2009. p. 3540. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Lehmkuhl H, Geffken GR, Jacob M, Ricketts E, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder: A non-randomized comparison of intensive and weekly approaches. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(7):1146–58. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akrami N, kalantari M, Arizi HR, Abedi MR, Maroufi M. Comparison of the Effectiveness of Behavioral-Cognitive and Behavioral Meta Cognitive Approaches in Patient with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Journal of Clinical Psycology. 2010;2(2):59–71. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arroll B, Macgillivray S, Ogston S, Reid I, Sullivan F, Williams B, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs compared with placebo for treatment of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(5):449–56. doi: 10.1370/afm.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishop JR, Chae SS, Patel S, Moline J, Ellingrod VL. Pharmacogenetics of glutamate system genes and SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. Psychiatry Res. 2012;199(1):74–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aukst-Margetić B, Margetić B. An open-label series using loratadine for the treatment of sexual dysfunction associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(5):754–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziaee T, Jannati Y, Mobasheri E, Taghavi T, Abdollahi H, Modanloo M, et al. The relationship between marital and sexual satisfaction among married women employees at Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2014;8(2):44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zohar J. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Current Science and Clinical Practice. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan SL. A Self-Rated Scale for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J Clin Psychol. 1994;50(4):564–74. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-19890201-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghassamia M, Asghari A, Shaeiri MR, Safarinejad MR. Validation of psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Female Sexual Function Index. Urol J. 2012;10(2):878–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kupfer DJ, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Roberts LW. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. Sixth Edition. American Psychiatric Pub; 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson JM. SSRI antidepressant medications: adverse effects and tolerability. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(1):22–7. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v03n0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irons J. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(4):289–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ackerman DL, Greenland S, Bystritsky A. Side effects as predictors of drug response in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):459–65. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199910000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen RC, Lane RM, Menza M. Effects of SSRIs on sexual function: a critical review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(1):67–85. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199902000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingsberg SA, Woodard T. Female sexual dysfunction: focus on low desire. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):477–86. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevenson JM, Bishop JR. Genetic determinants of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor related sexual dysfunction. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15(14):1791–806. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khazaie H, Rezaie L, Rezaei Payam N, Najafi F. Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction during treatment with fluoxetine, sertraline and trazodone; a randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(1):40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergh SJ, Giraldi A. Sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents. Ugeskrift for laeger. 2014;176(22) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldinger MD, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B. Antidepressants and ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized, fixed-dose study with mirtazapine and paroxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(5):467–70. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000088904.24613.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prabhakar D, Balon R. How do SSRIs cause sexual dysfunction? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uphouse L. Pharmacology of serotonin and female sexual behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;121:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahrold TK, Meston CM. Effects of SNS activation on SSRI-induced sexual side effects differ by SSRI. J Sex Marital Ther. 2009;35(4):311–9. doi: 10.1080/00926230902851322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balon R. SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1504–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franklin ME, Abramowitz JS, Bux DA, Jr, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with and without medication in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2002;33(2):162. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.33.2.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vulink NC, Denys D, Bus L, Westenberg HG. Sexual pleasure in women with obsessive-compulsive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2006;91(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aksaray G, Yelken B, Kaptanoğlu C, Oflu S, Ozaltin M. Sexuality in women with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27(3):273–7. doi: 10.1080/009262301750257128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laurent SM, Simons AD. Sexual dysfunction in depression and anxiety: conceptualizing sexual dysfunction as part of an internalizing dimension. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(7):573–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aksoy UM, Aksoy ŞG, Maner F, Gokalp P, Yanik M. Sexual dysfunction in obsessive compulsive disorder and panic disorder. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(4):381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asoodeh MH, Daneshpour M, Khalili S, Lavasani MG, Shabani MA, Dadras I. Iranian successful family functioning: Communication. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011;30:367–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Minnen A, Kampman M. The interaction between anxiety and sexual functioning: a controlled study of sexual functioning in women with anxiety disorders. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2000;15(1):47–57. doi: 10.1080/14681990050001556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montejo AL, Prieto N, Terleira A, Matias J, Alonso S, Paniagua G, et al. Better sexual acceptability of agomelatine (25 and 50 mg) compared with paroxetine (20 mg) in healthy male volunteers. An 8-week, placebo-controlled study using the PRSEXDQ-SALSEX scale. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(1):111–20. doi: 10.1177/0269881108096507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosen-Grandon JR, Myers JE, Hattie JA. The relationship between marital characteristics, marital interaction processes, and marital sastisfaction. Journal of Counseling and Development: JCD. 2004;82(1):58–68. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00286.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]