Abstract

Whereas enhanced peripheral T-cell apoptosis and its association with autoimmunity have recently been reported, the apoptotic status of peripheral B cells in chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains ambiguous. We therefore sought to investigate the sensitivity of peripheral B cells to apoptosis and to assess the possible benefits of antiviral treatment in mitigating these effects. Spontaneous apoptosis, the extent of apoptosis rescue, and NF-κB expression in peripheral B cells were studied in patients with chronic HCV infections (group 1), in sustained responders after antiviral treatment (group 2), and in healthy controls (group 3). For group 1, spontaneous B-cell apoptosis was increased (26% ± 4.6%) and apoptosis rescue was altered (39%) compared to group 3 (18% ± 5% and 50%, respectively; P = 0.001). In contrast, apoptosis and apoptosis rescue were similar for groups 2 and 3. Enhanced B-cell apoptosis was associated with decreased NF-κB expression and was found only in CD5-negative (CD5neg) B cells, whereas CD5pos cells were apoptosis resistant. Chronic HCV infection is associated with enhanced peripheral B-cell apoptosis and decreased apoptosis rescue. Successful antiviral treatment reverses these abnormalities to the levels seen in healthy individuals. The relative resistance of the CD5pos B-cell subpopulation to apoptosis may play a role in HCV-related autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is considered to be the leading cause of chronic liver disease, with a prevalence rate of between 0.5 and 2% in Western countries and up to 10% in certain non-Western countries (12). The spontaneous resolution of chronic HCV infection is rare, suggesting that the virus actively evades the immune system and limits its ability to garner an effective response (2, 4). However, little is known about how this virus persists and whether its persistence is due to early innate or adaptive immune response alterations. It was recently and elegantly shown that the binding of the HCV envelope protein E2 to CD81 inhibits natural killer (NK) cell antiviral activity, allowing the persistence of HCV and the establishment of a chronic infection (5, 34). Although CD81 ligation by HCV E2 was demonstrated to costimulate T cells, members of our laboratory reported an enhanced level of peripheral T-cell apoptosis in chronic HCV infections and suggested that this increase could contribute to both viral persistence and disease severity (32). That study demonstrated a decreased expression of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) in activated T cells of HCV-infected patients. Both enhanced apoptosis and decreased NF-κB expression correlated with autoimmune markers such as circulating cryoglobulins and rheumatoid factor (RF). The pathogenetic link between HCV and B-cell lymphotropism in inducing both autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation is unclear. The persistence of HCV in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), particularly in B cells, results in the chronic stimulation of B cells, leading to the polyclonal and later monoclonal proliferation of cells producing RF {also known as immunoglobulin M(κ) [IgM(κ)]} (29).

The recent identification of the CD81 protein as one of the HCV receptor candidates on B lymphocytes (27) suggests a mechanism by which B cells are infected with or, alternatively, activated by HCV and raises several interesting issues regarding the pathogenetic link between HCV persistence, autoimmunity, and lymphoproliferative disorders. Cross-linking of the signaling complex on B cells, which includes CD19, CD21, and CD81, by HCV particles may lower the threshold for B-cell activation and proliferation, explaining (at least in part) the association between chronic HCV infection, B-cell activation, and lymphoproliferation (16). Recently, Curry and colleagues have shown that the population of peripheral CD5-positive (CD5pos) B cells (i.e., RF-producing cells) is expanded during chronic HCV infection (6). In addition, members of our laboratory have demonstrated an association between CD5pos expansion and CD81 overexpression on peripheral B cells, markers of autoimmunity (RF and mixed cryoglobulin), and disease severity in patients who are chronically infected with HCV (39). However, the apoptotic status of peripheral B cells in HCV infection and its relation to autoimmunity remained ambiguous.

The present study consequently examined the degree to which HCV infection affects B-cell apoptosis and was designed to assess the possible benefit of antiviral treatment in reversing apoptosis abnormalities. Our findings suggest a strong association between enhanced B-cell apoptosis and HCV-related autoimmunity. Whereas enhanced apoptosis occurred mainly in CD5neg B cells, CD5pos B cells were apoptosis resistant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Twenty-seven patients with chronic HCV infections (16 females and 11 males; mean age, 47 years [range, 36 to 59 years]) were studied. All patients were untreated, were positive for anti-HCV antibodies (ELISA II; Abbot Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.), and had detectable HCV RNA (Amplicor PCR assay; Roche Molecular Systems, Somerville, N.J.) and histological evidence of chronic hepatitis, with or without cirrhosis (untreated; group 1). Twenty-one of these patients were then treated with a combined antiviral therapy (standard or pegylated alpha interferon [IFN-α] and ribavirin). Ten patients achieved a sustained virological response (i.e., there was no detectable HCV RNA at least 6 months after the completion of treatment). These sustained responders were restudied for the same parameters as group 1 (treated; group 2). A third group (group 3) included 30 age- and sex-matched healthy individuals. All HCV-infected patients were monitored at the Liver Clinic of Bnai Zion Medical Center. All subjects underwent measurements of the following serological and biochemical parameters: alanine and aspartate aminotransferases, cryoglobulins, antinuclear antibodies to HEP-2, anti-smooth muscle and anti-cardiolipin antibodies, and RF. Liver disease severity was assessed on the basis of the alanine aminotransferase level in serum and the liver histology.

Informed consent was obtained from each patient, and the study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected by a priori approval by the Bnai Zion Medical Center Human Research Committee.

HCV quantification.

HCV RNA concentrations in sera were measured with an Amplicor Monitor test kit (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Basel, Switzerland). The test kit includes an RNA quantification standard of a known copy number that is coamplified with the target and is used to calculate the copy level of the sample by a colorimetric assay after hybridization to a specific probe.

Histological analysis.

Histological scores were graded from 0 to 22, as modified from the work of Knodell et al. (14). The Knodell histological activity index (HAI), an inflammation score, was obtained by combining the scores for periportal injury (interface hepatitis and/or bridging necrosis) (0 to 10), parenchymal injury (0 to 4), portal inflammation (0 to 4), and fibrosis (0 to 4). An independent histopathologist who was unaware of the clinical status of the patients evaluated the degree of inflammation and fibrosis.

Cryoglobulin detection and analysis.

Venous blood samples were collected into prewarmed tubes after an overnight fast and were allowed to clot at 37°C. After centrifugation, the sera were incubated at 4°C for 3 days. The cryocrit was evaluated by centrifugation of the serum in hematocrit tubes at 4°C. Cryoprecipitates were further analyzed and characterized by immunofixation electrophoresis (Immunofix kit; Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, Tex.).

B-cell analyses.

PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient separation. Washed PBMCs were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, l-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin in 24-well plates (Corning Glass Works, Corning, N.Y.) at a final concentration of 106 cells/well. The cells were incubated in culture medium with and without 1 μg of anti-IgM F(ab)2 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark)/ml and 10 U of recombinant interleukin-4 (IL-4) (Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, Mass.)/ml for 24 h.

The CD19+ B-cell populations from all studied groups were assessed for their sensitivity to spontaneous apoptosis (annexin V binding on gated CD19+ cells). The sensitivity of B lymphocytes to being rescued by IL-4 and anti-IgM F(ab)2 was also compared for all groups. The induction of apoptosis was separately assessed for CD5pos and CD5neg B cells.

Assessment of apoptotic cell death. (i) Flow cytometry.

Annexin V binding to B (CD19) cells was assayed by direct (one step) double immunostaining with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibody (MAb) to annexin V (annexin V kit; MedSystems Diagnostics GmbH, Vienna, Austria) and a phycoerythrin-conjugated MAb to CD19 (Genzyme Corporation). In order to detect whether CD5pos B cells demonstrated a different susceptibility to the induction of apoptosis, we used a third color (in addition to CD19-phycoerythrin and annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate), namely, an allophycocyanin-conjugated MAb to CD5 (Dako). Flow cytometry was performed by use of a fluorescence-activated cell sorter operating with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

The total population of viable cells was gated according to their typical amounts of forward and right-angle light scatter. The fluorescence of cells that were treated with a fluorescent isotype MAb was evaluated in each experiment to determine the level of background fluorescence of negative cells. The percentage of cells that stained for annexin V, CD19, and CD5pos was determined by counting a total of 40,000 cells taken from independent replicates, taking only positive cells into account.

(ii) DAPI staining.

In order to confirm morphologically the finding of enhanced B-cell apoptosis, we performed 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Briefly, cultured B cells were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 70% ethanol for 20 min at room temperature, and washed again with 1× PBS. The cells were then treated with DAPI (1 mg/ml; Sigma) at a 1:1,000 dilution, incubated for 10 min, and washed again with 1× PBS for 5 min. Stained nuclei were visualized under a fluorescence microscope. Apoptotic cells were morphologically defined by cytoplasmic and nuclear shrinkage and chromatin condensation or fragmentation. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as a proportion of 250 total cells visualized in 10 different fields of each slide per experiment.

NF-κB and Bcl-2 detection by Western immunoblotting.

After B-cell activation with or without pokeweed mitogen, the cells were washed with PBS and lysed in sodium dodecyl sulfate lysis buffer as described by Towbin et al. (33). Equal amounts of protein, measured by the method of Lowry et al. (17), were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated with an anti-NF-κB p-50 MAb together with a loading control of activated Jurkat cells (Allexis Biochemicals, San Diego, Calif.) and an anti-Bcl-2 MAb (Ancell, Bayport, Minn.).

Western blot analysis.

The immunoblot bands were scanned with a 1200 ED scanner device (Mustek, Hamburg, Germany) at an optical resolution of 2,832 by 1,864 pixels. The obtained image was then analyzed with image analysis software (Image Pro Plus, v. 4.5; MediaCybernetics).

Statistical analysis.

Using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, we found that the continuous variables were distributed normally. A comparison of continuous variables between the HCV patients and their matched controls was performed by using the paired student t test. The Pearson's coefficient of correlation was calculated in order to test the relationship between the extent of annexin V binding and the decrease in NF-κB expression. Associations between annexin V binding and clinical or serological findings were tested by using Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Two-tailed P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The clinical and serological characteristics of the three patient groups studied are presented in Table 1. The HCV-infected patients, sustained responders, and healthy controls were comparable with respect to age and gender. Note that there was a significantly lower level of one or more autoimmune markers (i.e., anti-nucleus, anti-smooth muscle, and anti-cardiolipin antibodies) as well as a reduction (not statistically significant) in the presence of cryoglobulinemia after successful antiviral treatment in the sustained responders.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of HCV-infected patientsa

| Group (n) | Age (yrs) (mean ± SD) | No. of females/no. of males | HAIb (mean ± SD) | Mean HCV RNA titer (105 copies/ml) | No. (%) of patients with autoantibodies | No. (%) of patients with cryoglobulins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated HCV-positive patients (27) | 47 ± 12 | 16/11 | 8.4 ± 3.5 | 6.1 ± 2.3 | 18 (66) | 9 (33) |

| Treated, HCV-negative patients (10) | 46 ± 16 | 6/4 | Negative | 3 (33) | 2 (20) | |

| Healthy patients (30) | 44 ± 14 | 16/14 | 0 |

The difference in the numbers of patients with autoantibodies was significant, with a P value of 0.045. All other differences in the variables between groups were not significant.

HAI, histological activity index.

Flow cytometry analysis of B-cell apoptosis.

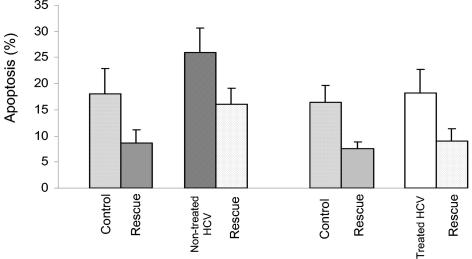

The level of spontaneous apoptosis of cultured B cells, as detected by annexin V binding, was significantly higher in untreated HCV-infected patients than in healthy individuals (26% ± 4.6% versus 18% ± 5%; P < 0.0001 by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 1). When anti-IgM F(ab)2 and IL-4 were added to the culture, the extent of decreased (rescued) B-cell apoptosis among untreated HCV patients was significantly lower than that for healthy controls (39 versus 50%; P < 0.0001 by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

B-cell apoptosis and apoptosis rescue in HCV-infected patients. The spontaneous apoptosis of cultured B cells (as detected by annexin V binding) was significantly higher, whereas apoptosis rescue was lower, in untreated HCV patients than in healthy controls (P < 0.0001). Successful antiviral treatment reversed these abnormalities, as B-cell apoptosis and apoptosis rescue were comparable in HCV-treated patients and healthy controls (P = 0.3 and 0.26, respectively).

No significant difference was detected when we compared the spontaneous apoptosis of B cells from sustained responders (group 2) to that of cells from healthy individuals (18.2% ± 4.6% versus 16.4% ± 3.2%; P = 0.3 by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 1). Moreover, the extent of apoptosis rescue for this group was also similar to that of healthy controls (50 versus 58%; P = 0.26 by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 1).

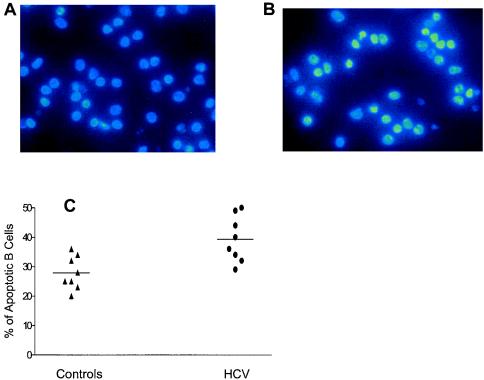

In order to confirm these results, we also assessed B-cell apoptosis by DAPI staining of cells from eight patients. The percentage of B cells exhibiting typical features of apoptosis, such as chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation, was significantly higher for untreated HCV-infected patients than for healthy individuals (39% ± 7.8% versus 28% ± 5.6%; P = 0.004 by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

B-cell apoptosis (as assessed by DAPI staining). Apoptotic cells were morphologically defined by cytoplasmic and nuclear shrinkage and chromatin condensation or fragmentation. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as a proportion of 250 total cells visualized in 10 different fields of each slide per experiment. (A) Representative slide of B cells from a healthy control, with few apoptotic cells. (B) Representative slide of B cells from an untreated HCV-infected patient, with numerous apoptotic cells (condensed or fragmented nuclei). (C) Percentages of apoptotic cells from healthy controls and untreated HCV-infected patients.

In order to assess whether alterations in spontaneous apoptosis are unique to HCV infection, we also measured the apoptosis of cultured B cells, as detected by annexin V binding, for 10 patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infections and found the level of apoptosis to be comparable with that in healthy individuals (19.5% ± 2.7% versus 19.7% ± 2.4%; P = 0.9 by paired Student's t test). The extent of apoptosis rescue was also similar for both groups.

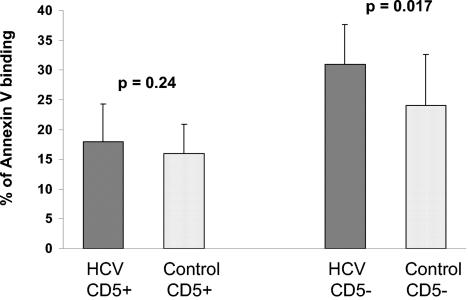

Since CD5pos B cells may be a relevant subpopulation with respect to HCV autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation, we separately analyzed the extent of apoptosis among these cells and CD5neg cells from those patients who were chronically infected with HCV (group 1). Interestingly, the CD5neg B cells underwent a significantly higher rate of spontaneous apoptosis than did cells from healthy individuals (31% ± 6.7% versus 24% ± 8.6%; P = 0.017 by paired Student's t test). In contrast, the level of spontaneous apoptosis in CD5pos B cells was similar to that in healthy controls (18% ± 6.3% versus 16% ± 4.9%; P = 0.24 by paired Student's t test), indicating that these cells are relatively protected from the enhanced apoptosis seen in other B cells (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Apoptosis of CD5pos versus CD5neg B lymphocytes in HCV-infected patients. While spontaneous CD5neg B-cell apoptosis was enhanced, the apoptosis of CD5pos cells was similar to that of healthy controls.

Association between apoptosis and autoimmunity.

Whereas enhanced B-cell apoptosis in the patients infected with HCV was strongly associated with the appearance of autoimmune markers (P = 0.008 by Fisher's exact test), the return of apoptosis to the baseline level (i.e., the level of healthy controls) after HCV clearance was accompanied by a significant decrease in the presence of these markers. Furthermore, despite the association between enhanced B-cell apoptosis and autoimmune markers in HCV-infected patients, no association was found between B-cell apoptosis and the HAI, RNA viral load, or cryoglobulinemia. Nevertheless, while the number of patients with cryoglobulinemia was too small to allow significance testing, a positive association between the apoptosis resistance of CD5pos B cells and the presence of cryoglobulinemia was identified.

NF-κB and Bcl-2 expression.

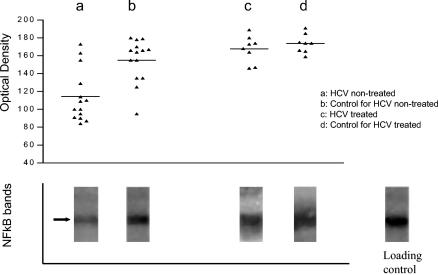

NF-κB and Bcl-2 expression could not be demonstrated in resting B cells (data not shown). The mean optical density values of NF-κB bands in pokeweed mitogen-activated B cells from untreated HCV patients (data were available for only 14 patients) were found to be significantly decreased compared with those for healthy individuals (114 ± 29 versus 155 ± 24; P = 0.004 by paired Student's t test). However, the expression of NF-κB in B cells from eight successfully treated HCV patients was comparable to that for healthy individuals (164 ± 15 versus 174 ± 10; P = 0.32 by paired Student's t test) (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference in Bcl-2 expression in B cells from all three groups (i.e., untreated patients, sustained responders, and healthy controls). In order to ensure that these results were quantitatively true, we loaded similar amounts of lysed B cells into each lane.

FIG. 4.

NF-κB expression in B cells of HCV-infected patients. The graph shows optical density values of NF-κB expression (as determined by Western immunoblotting) in activated B cells from the studied groups. The gels show representative NF-κB bands (arrow) of all groups and of a loading control. NF-κB expression was decreased in untreated patients (a) compared with healthy controls (b). Successful antiviral treatment reversed the decrease in NF-κB to a level comparable to that of healthy controls (c and d).

Correlation between apoptosis and NF-κB expression.

The decrease in NF-κB expression in B cells from untreated patients (group 1) was inversely correlated with the extent of spontaneous apoptosis of B cells (Pearson's r = −0.71; P = 0.004). However, while the decrease in NF-κB expression was associated with an increased presence of autoimmune markers (P = 0.01 by Fisher's exact test), such an association could not be demonstrated with respect to either the HAI score or the HCV viral load.

DISCUSSION

Several immune function alterations have been proposed to explain the persistence of chronic infections of HCV (2, 4, 15) and its association with an increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders (30). Suggested mechanisms by which HCV may alter host innate immunity involve the attenuation of IFN-γ production by inhibited NK cells after the engagement of CD81 by the envelope protein E2 (5, 34). This insufficient production of IFN-γ could prevent the adaptive immune response from being skewed in favor of a Th1 inflammatory response (25, 28). Supporting this hypothesis is the previous finding of enhanced T-cell apoptosis in patients with chronic HCV infections, which may down-regulate the cellular immune response and lead to infection persistence (32).

However, the apoptotic status of B lymphocytes in chronic HCV infection has not been widely investigated. Numerous studies have shown that HCV infection may induce monoclonal B-cell expansion and the production of mixed cryoglobulins (1, 8, 20, 22, 30). Furthermore, it has been suggested that the expanded B-cell clones may have an extended survival time due to decreased apoptosis (13, 37, 40). However, Giannini and colleagues were not able to demonstrate a significant modification of apoptotic pathways by the HCV core protein in transfected B-cell lines (9).

In contrast to our initial assumption, the present study demonstrated an increased sensitivity of peripheral B cells to spontaneous apoptosis along with a variable ability to be rescued. Whereas most of the peripheral B-cell population (i.e., CD5neg cells) underwent enhanced apoptosis, a subpopulation, namely the CD5pos cells, was relatively protected and was comparable to that in healthy individuals. Generally, these unique B cells are characterized by the production of low-affinity IgM with RF activity, arise early in ontogeny, and are considered to represent the bridge linking the innate and acquired immune responses (10, 35). In addition, CD5pos B cells are also increased in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia and were identified as monoclonal and polyclonal IgM-producing cells in the hepatic lymphoid follicles of HCV-infected patients (21, 26). Interestingly, the expansion of this B-cell subpopulation has been reported for autoimmune disorders (7, 11, 18) and recently also for chronic HCV infection (6, 39). The expansion of CD5pos cells and their resistance to apoptosis may be responsible for the continuous monoclonal RF and cryoglobulin production and may represent the link between HCV infection, autoimmunity, and lymphoproliferation. However, the mechanism by which HCV induces expansion and interferes with the apoptotic death of these cells remains unclear.

Although B cells are not the major producers of cytokines, CD5pos B cells are an important source of immunoregulatory cytokines such as IL-10. By extending the survival of B cells, IL-10 may play a role in the rescue of CD5pos B cells from apoptosis (23, 24). The mechanism underlying the different sensitivities to apoptosis induction of CD5pos and CD5neg cells requires further clarification. It is possible, as suggested by Giannini et al. (9), that the effect of HCV is cell type specific. Specifically, the relatively high prevalence of HCV-infected CD5pos B cells may support this assumption.

Our findings in the present study suggest that the increased apoptosis sensitivity of CD5neg B cells contributes to HCV-related autoimmunity. A possible explanation for this is that the enhanced apoptosis of B lymphocytes may increase the release of intact nuclear auto-antigens and the development of autoimmunity (31). Consequently, HCV persistence could be a catalyst for the repeated generation of apoptotic material and for continual challenging of the primed immune system.

Our finding of reduced NF-κB expression in activated peripheral B lymphocytes from patients suffering from chronic HCV infections is important to our understanding of the enhanced apoptosis of these cells. NF-κB is an important transcription factor that plays an essential role in the regulation of the immune response, cell apoptosis, inflammation, oncogenesis, viral replication, and various autoimmune diseases. A series of recent publications have pointed to a relationship between NF-κB activity and the protection of certain cells from apoptosis (3). However, our finding of decreased NF-κB expression alone may not sufficiently explain the mechanism of the altered apoptotic status of B cells in infected patients.

Both an anti-IgM antibody and IL-4 induced protection against normal adult B-cell apoptosis by increasing the expression of antiapoptotic molecules. IL-4-induced antiapoptotic activities have been shown to be promoted by various signaling proteins, such as IRS-2 and Stat6, and by protein tyrosine phosphatase activity (36). In healthy mature human B cells, relatively weak cross-linking of surface IgM (sIgM) may induce DNA synthesis and cell proliferation, whereas intense cross-linking may induce apoptotic cell death (19). With respect to these aforementioned mechanisms, one may speculate that HCV down-regulates NF-κB expression by interfering with both IL-4 and sIgM signaling, thus limiting their apoptosis rescue ability. The possible intensification of sIgM signaling by HCV may also contribute to changes in the sensitivity of these cells to apoptosis and rescue.

Our other important finding was the beneficial effect of antiviral treatment in correcting B-cell apoptosis abnormalities. Among patients with a sustained virological response, the disappearance of HCV RNA was accompanied by a reversal of enhanced apoptosis and decreased rescue to the baseline level, i.e., the level seen in healthy controls. Importantly, the correction of apoptotic alterations by antiviral treatment occurred in parallel with the reverse of decreased B-cell NF-κB expression. Moreover, successful HCV clearance was also associated with a significantly lower rate of the presence of autoimmune markers. In a recent study (38), members of our laboratory demonstrated that antiviral therapy resulted in a decrease in both CD81 overexpression and CD5pos B-cell expansion in patients with chronic HCV infections. This beneficial effect may be explained by an attenuation of the continued activation of B cells by viral particles and a discontinuation of HCV interference with intracellular signals that are responsible for the down-regulation of NF-κB expression.

This is the first study demonstrating the potential effect of antiviral therapy in correcting various alterations in the sensitivity of B cells to spontaneous apoptosis followed by a reduction in autoimmune markers in patients who are chronically infected with HCV.

Future studies should be designed to enhance our understanding of the precise intracellular events that protect CD5pos B cells from apoptosis and at the same time promote apoptosis in CD5neg B cells. Researchers should also examine the role of such processes in the development of HCV-related autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agnello, V., R. T. Chung, and L. M. Kaplan. 1992. A role for hepatitis C virus infection in type II cryoglobulinemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 327:1490-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter, H. J., and L. B. Seeff. 2000. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus infection: a perspective on long term outcome. Semin. Liver Dis. 20:17-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beg, A. A., and D. Baltimore. 1996. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science 274:782-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerny, A., and F. V. Chisari. 1999. Pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C: immunological features of hepatic injury and viral persistence. Hepatology 30:595-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crotta, S., A. Stilla, A. Wack, A. D'Andrea, S. Nuti, U. D'Oro, M. Mosca, F. Filliponi, R. M. Brunetto, F. Bonino, S. Abrignani, and N. B. Valiante. 2002. Inhibition of natural killer cells through engagement of CD81 by the major hepatitis C virus envelope protein. J. Exp. Med. 195:35-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curry, M. P., L. Golden-Mason, N. Nolan, N. A. Parfrey, J. E. Hegarty, and C. O'Farrelly. 2000. Expansion of peripheral blood CD5+ B cells is associated with mild disease in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol. 32:121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dauphinee, M., Z. Tovar, and N. Talal. 1988. B cells expressing CD5 are increased in Sjögren's syndrome. Arthrit. Rheum. 31:642-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franzin, F., D. G. Efremov, G. Pozzato, P. Tulissi, F. Batista, and O. R. Burrone. 1995. Clonal B cell expansion in peripheral blood of HCV-infected patients. Br. J. Hematol. 90:548-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giannini, C., P. Caini, F. Giannelli, F. Fontana, D. Kremsdorf, C. Brechot, and A. L. Zigrego. 2002. Hepatitis C virus core protein expression in human B cell lines does not significantly modify main proliferative and apoptosis pathways. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1665-1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy, R. R., K. Hayakawa, M. Shimizu, K. Yamasaki, and T. Kishimoto. 1987. Rheumatoid factor secretion from human Lec-1+ B cells. Science 236:81-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassan, J., C. Feighery, B. Bresniham, and A. Whelan. 1990. Increased CD5+ B cells in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Br. J. Haematol. 74:375-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoofnagle, J. H., and T. S. Tralka. 1997. The National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on Management of Hepatitis C Virus. Introduction. Hepatology 26(Suppl. 1):1S-2S. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitay-Cohen, Y., A. Amiel, N. Hilzenrat, D. Buskila, Y. Ashur, M. Fejgin, F. Gaber, R. Safadi, R. Tur-Kaspa, and M. Lishmer. 2000. Bcl-2 rearrangement in patients with chronic hepatitis C associated with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia type II. Blood 96:2910-2912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knodell, R. G., K. G. Ishak, W. C. Black, T. S. Chen, R. Craig, N. Kaplowitz, T. W. Kieman, and J. Wollman. 1981. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology 1:431-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai, M. M. C., and C. F. Ware. 1999. Hepatitis C virus core protein: possible roles in viral pathogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 242:117-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy, S., S. C. Todd, and H. T. Maecker. 1998. CD81, a molecule involved in signal transduction and cell adhesion in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:89-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. Randell. 1951. Protein measurement with the folin reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mariette, X. 2001. Lymphomas complicating Sjogren's syndrome and hepatitis C virus infection may share a common pathogenesis: chronic stimulation of rheumatoid factor B cells. Clin. Rheum. Dis. 60:1007-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayumi, M., S. Sumimoto, S. Kanazashi, D. Hata, K. Yamaoka, Y. Higaki, T. Ishigami, K. M. Kim, T. Heike, and K. Katamura. 1996. Negative signaling in B cells by surface immunoglobulins. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 98:S238-S247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misiani, R., P. Bellavita, D. Fenili, G. Borelli, D. Marchesi, M. Massazza, G. Vendramin, B. Comotti, E. Tanzi, and G. Scudeller. 1992. Hepatitis C infection in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Ann. Int. Med. 117:573-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monteverde, A., M. Ballare, and S. Pileri. 1997. Hepatic lymphoid aggregates in chronic hepatitis C and mixed cryoglobulinemia. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 19:99-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monteverde, A., M. T. Rivano, G. C. Allegra, A. I. Monteverde, P. Zigrossi, P. Baglioni, M. Gobbi, B. Falini, G. Bordin, and S. Pileri. 1988. Essential mixed cryoglobulinemia, type II: a manifestation of a low-grade malignant lymphoma? Acta Hematol. 79:20-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Garra, A., R. Chang, N. Go, R. Hasyings, G. Haughton, and M. Howard. 1992. Ly-1 B (B-1) cells are main source of B cell-derived interleukin 10. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:711-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pers, J. O., C. Jamin, F. Prendine-Hug, P. Lydyard, and P. Youinou. 1999. The role of CD5-expressing B cells in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 3:239-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piazolla, G., C. Tortorella, O. Schiraldi, and S. Antonaci. 2000. Relationship between interferon-gamma, IL-10, and IL-12 production in chronic hepatitis C and in vitro effects of interferon-alpha. J. Clin. Immunol. 20:541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pietrogrande, M., M. Corona, S. Milani, A. Rosti, M. Ramella, and G. Tordato. 1995. Relationship between rheumatoid factor and the immune response against hepatitis C virus in essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 13(Suppl. 13):S109-S113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pileri, P., Y. Uematsu, S. Campagnoli, G. Galli, F. Falugi, R. Petracca, A. J. Weiner, M. Houghton, D. Rosa, G. Grandi, and S. Abrignani. 1998. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282:938-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarih, M., N. Bouchrit, and A. Beslimane. 2000. Different cytokine profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with persistent and self-limited hepatitis C virus infection. Immunol. Lett. 74:117-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sasso, E. H. 2000. The rheumatoid factor response in the etiology of mixed cryoglobulinemia associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Ann. Med. Interne (Paris) 15:30-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silvestri, F., A. Sperotto, and R. Fanin. 2000. Hepatitis C and lymphoma. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2:172-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sung, V. M., S. Shimodaria, A. L. Doughty, G. R. Picchio, H. Can, T. S. Yen, K. L. Lindsay, A. M. Levine, and M. M. Lai. 2003. Establishment of B-cell lymphoma cell lines persistently infected with hepatitis C virus in vivo and in vitro: the apoptotic effects of virus infection. J. Virol. 77:2134-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toubi, E., A. Kessel, L. Goldstein, G. Slobodin, E. Sabo, Z. Shmuel, and E. Zuckerman. 2001. Enhanced peripheral T-cell apoptosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: association with liver disease severity. J. Hepatol. 35:774-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tseng, C. K., and G. R. Klimpel. 2002. Binding of hepatitis C virus envelope protein E2 to CD8 inhibits NK cell function. J. Exp. Med. 195:43-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuji, R. F., G. P. Geba, Y. Wang, K. Kawamoto, L. A. Matis, and P. W. Askenase. 1997. Required early complement activation in contact sensitivity with generation of local C5-dependent chemotactic activity and late T cell interferon gamma: a possible initiating role of B cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:1015-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wurster, A. L., D. J. Withers, T. Ucida, M. F. White, and M. J. Grusby. 2002. Stat6 and IRS-2 cooperate in interleukin 4 (IL-4)-induced proliferation and differentiation but are dispensable for IL-4-dependent rescue from apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:117-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zignego, A. L., F. Giannelli, M. E. Marrocchi, A. Mazzocca, C. Ferri, C. Giannini, M. Monti, P. Caini, G. L. Villa, G. Laffi, and P. Gentilini. 2000. T(14:18) translocation in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 31:474-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zuckerman, E., A. Kessel, G. Slobodin, E. Sabo, D. Yeshurun, and E. Toubi. 2003. Antiviral treatment down-regulates peripheral B-cell CD81 expression and CD5 expansion in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 77:10432-10436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuckerman, E., G. Slobodin, A. Kessel, E. Sabo, D. Yeshurun, K. Halas, and E. Toubi. 2002. Peripheral B-cell CD5 expansion and CD81 overexpression and their association with disease severity and autoimmune markers in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 128:353-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuckerman, E., T. Zuckerman, D. Sahar, S. Steichman, D. Attias, E. Sabbo, D. Yeshurun, and J. Rowe. 2001. Bcl-2 and immunoglobulin gene rearrangement in patients with HCV infection. Br. J. Haematol. 112:364-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]