Abstract

To characterize polymorphisms of the subtype A protease in the former Soviet Union, proviral DNA samples were obtained, with informed consent, from 119 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-positive untreated injecting drug users (IDUs) from 16 regions. All individuals studied have never been treated with antiretroviral drugs. The isolates were defined as IDU-A (n = 115) and CRF03_AB (n = 4) by using gag/env HMA/sequencing. The pro region was analyzed by using sequencing and original HIV-ProteaseChip hybridization technology. The mean of pairwise nucleotide distance between 27 pro sequences (23 IDU-A and 4 CRF03_AB) was low (1.38 ± 0.79; range, 0.00 to 3.23). All sequences contained no primary resistance mutations. However, 13 of 23 (56.5%) subtype A isolates bore the V77I substitution known as the secondary protease mutation. V77I was associated with two synonymous substitutions in triplets 31 and 78, suggesting that all V77I-bearing viruses evolved from a single source in 1997. Hybridization analysis showed that 55 of 115 (47.8%) HIV-1 isolates contained V77I, but this variant was not found in any of 31 DNA samples taken from regions, where the HIV-1 epidemic among IDUs started earlier 1997, as well as in any of four CRF03_AB isolates. The results of analysis of 12 additional samples derived from epidemiologically linked subjects showed that in all four epidemiological clusters the genotype of the donor and the recipients was the same irrespective of the route of transmission. This finding demonstrates the transmission of the V77I mutant variant, which is spreading rapidly within the circulating viral pool in Russia and Kazakhstan. The continued molecular epidemiological and virological monitoring of HIV-1 worldwide thus remains of great importance.

Combined antiretroviral therapy with three to four drugs has substantially reduced the morbidity and mortality of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (14, 33). There are now 17 antiretroviral drugs approved for treatment of HIV-1-infected patients in the Russian Federation (37). The drugs target two enzymes essential for viral replication, reverse transcriptase (RT) and protease. The action of RT inhibitors (nucleoside analogues, nucleoside RT inhibitors [NRTIs], and nonnucleoside inhibitors [NNRTIs]) is to suppress a relatively early step in virus replication: the reverse transcription of viral RNA to cDNA. In contrast, protease inhibitors (PIs) act later in the virus life cycle. The HIV-1 protease is a homodimer consisting of two 99-amino-acid subunits. This enzyme cleaves Gag and Gag-Pol precursor proteins into functional proteins during or after budding of virus particles from the plasma membrane (20). Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) usually consists of two complementary NRTIs and either an NNRTI or one or two PIs.

However, antiretroviral therapy may be complicated by the development of drug-resistant HIV-1 variants (35). Furthermore, both vertical and horizontal transmissions of drug-resistant HIV-1 variants have been demonstrated (9, 13). As more HIV-1-positive patients begin HAART, the proportion of drug-resistant variants, including the variants with multiple drug resistance, has been increasing in the population (1). Information concerning HIV-1 genetic variants bearing drug resistance mutations is thus extremely important both for treatment of a particular individual and for the estimation of drug resistance in the population.

All HIV-1 drug resistance mutations in the protease gene are subdivided into two groups. Primary mutations appear and lead to resistance, but as a consequence the replicative capacity of the virus is often decreased. Secondary mutations are not associated with drug resistance directly but both confer higher levels of resistance and improve viral fitness (8). The frequency of primary mutations in PI-naive populations is usually low; the frequency of the secondary mutations in such populations may be considerably higher (1). The use of drug resistance testing in developed countries has led to a great deal of information about drug resistance among subtype B isolates. Based on observations of the differences between sequences from untreated and treated subjects infected with subtype B viruses, mutations at some positions were characterized as secondary resistance mutations. On the other hand, these substitutions may be present in all or at least in the great majority of amino acids sequences from any other genetic subtype, thus reflecting baseline subtype-specific polymorphisms of the gag-pol gene (19).

At present, within the territory of the Russian Federation and a number of other former Soviet Union republics (the Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Uzbekistan, Georgia, and Azerbaijan) HIV-1 subtype A variants predominate, circulating among injecting drug users (IDUs) and their sexual partners (3, 6, 7, 23, 25, 27, 31, 32, 34; J. L. Sanchez, J. K. Carr, R. Graham, and E. T. Latta, Abstr. 11th Conf. Retroviruses Opportunistic Infect., 2004, abstr. 867; T. Smolskaya et al., Abstr. 2nd IAS Conf. HIV Pathog. Treatment, abstr. 244, p. 5243, 2003; V. Zetterberg, V. Ustina, K. Liitsola, N. Kalikova, K. Zilmer, H. Brummer-Korvenkontio, P. Leinikki, and M. Salminen, Abstr. XIV Int. AIDS Conf., abstract TuPeC4799, 2002). However, information concerning the genomic diversity of these viruses in the protease-encoded region is limited (25, 26, 28, 34; E. Vazquez de Parga et al., XIV Int. AIDS Conf., abstr. TuPeC4807, 2002). The main goal of the present study was to analyze the genetic variability of the gag-pol gene fragment encoding virus-specific protease among HIV-1 variants belonging to subtype A and the CRF03_AB forms characteristic in East Europe (4, 5, 25). To obtain such information, we analyzed HIV-1 genetic variants, along with conventional sequencing, by using oligonucleotide microarrays that have already been proven to be used as a diagnostic tool for identifying nucleic acid polymorphisms (24, 29, 41).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA lysates of peripheral blood mononuclear cells were taken from the collection of the Laboratory of T-Lymphotropic Viruses of the D. I. Ivanovsky Institute of Virology Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (Moscow), where they were kept at −70°C for periods of from several months to 7 years. Blood samples were derived from 27 IDUs, aged 17 to 32, diagnosed as HIV positive in the period from 1996 to 2002 in the Russian Federation (n = 21), the Ukraine (n = 3), and Kazakhstan (n = 3). All blood samples were obtained with informed consent and under approved human use protocols and were genotyped by using gag/env HMA and sequencing as described previously (4, 11, 17). Of the 27 virus samples examined, 23 belonged to HIV-1 genetic subtype A, typical of IDU populations in Eastern Europe (4, 7), and 4 were the CRF03_AB recombinant form (5, 25, 26). It was shown previously that the CRF03_AB protease gene belongs to genetic subtype A (26).

DNA samples derived from an additional 92 IDUs infected with HIV-1 during the period from 1995 to 2003 were analyzed by using HIV-ProteaseChip (see below) after we obtained informed consent. Moreover, according to the epidemiological data, at least 14 HIV-1-infected IDUs included into this cohort also reported unprotected heterosexual contacts with HIV-1-infected IDUs. In order to demonstrate possible transmission by both the wild type and the V77I mutant HIV-1 variants, HIV-ProteaseChip was also used to analyze 12 additional samples derived from epidemiologically linked HIV-1-positive subjects infected either via the sexual route of transmission or parenterally.

No patients studied were treated with HIV-1 PIs, at least not prior to the date of venipuncture for genetic analyses. Clinical and epidemiological data for all patients were obtained from the database of the Federal AIDS Centre, Moscow, Russia.

Oligonucleotides and primers.

Oligonucleotides were synthesized on an ABI-394 DNA/RNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) by using standard phosphoramidite chemistry. Oligonucleotides were purified by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on C18-Nucleosil columns (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). To immobilize oligonucleotides in gel pads of HIV-ProteaseChip or to attach the fluorescent label Texas red (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.) or cyanine dye (Cy-5 analogue; Biochip-IMB, Moscow, Russia), an amino group was introduced during synthesis using 3′-Amino-Modifier C7 CPG 500 or 5′-Amino-Modifier C6 (Glen Research, Sterling, Va.). The attachment of the fluorescent group to the amino group in oligonucleotides was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers were fluorescently labeled at their 5′ ends.

PCR.

The 316-bp HIV-1 pro fragment was amplified by nested PCR. At the first stage, a 379-bp fragment of the pol gene (positions 2217 to 2596 according to the genome of the HIV-1 group M strain HXB2 [GenBank accession no. K03455]) was amplified with the primers F2217 (5′-GGAACAGAAAGACAGGGAACAGCATCCTC-3′) and R2596 (5′-ATTCCTGGCTTTAATGTTACTGGTACAGTTTCAAT-3′). The reaction mixture contained 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 2.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer [PE] Corp., Norwalk, Conn.), 0.5 U of uracyl-DNA-glycosylase (Medigen, Moscow, Russia), 100 nM concentrations of each primer, 5 μl of DNA sample, and 0.2 mM (each) of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dUTP. The reaction was carried out in a minicycler (MJ Research, Waltham, Mass.) as follows: 10 min at room temperature; followed by 5 min at 95°C; followed by 40 cycles of 40 s at 95°C, 40 s at 60°C, and 40 s at 72°C; with a final 5 min at 72°C. Then, 2 μl of the reaction mixture obtained after the first reaction was used for the second-stage PCR.

To amplify an internal 316-bp fragment (positions 2249 to 2564 according to the genome of the HIV-1 group M strain HXB2) of the first product, the primers F2249 (5′-TTTCCCTCAAATCACTCTTTGGCAACGACC-3′) and R2564 (5′-AATAGGACTTATTGGAAAATTTAAAGTACAACCAA-3′) were used. The reaction mixture was the same as above except for the volume of DNA sample (2 μl), and no uracyl-DNA-glycosylase was added. The reaction was carried out in a minicycler as follows: 2 min at 95°C; followed by 40 cycles of 40 s at 95°C, 40 s at 60°C, and 40 s at 72°C; and finally 5 min at 72°C.

To prevent possible contamination, all samples were amplified in parallel at two different laboratories. In each set of reactions, two HIV-negative samples and two HIV-positive samples belonging to non-subtype A HIV-1 genetic subtypes were used as controls.

At the third stage, an asymmetric PCR was applied to produce the predominantly single-stranded fluorescently labeled product by using the HIV-ProteaseChip. The internal 299-bp fragment (positions 2253 to 2551 according to the genome of HIV-1 group M strain HXB2) was amplified with primers F2253 (5′-CCTCAGGTCACTCTTTGG-3′) and R2551 (5′-GGAAAATTTAAAGTGCAACCAATCTG-3′). The reaction mixture contained 1.5 mM MgCl2; 10 mM KCl; 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3); 2.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (PE Corp.); a 100 nM concentration of fluorescently labeled primer R2551; a 10 nM concentration of F2253; 0.2 mM concentrations(each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; and 1 μl of DNA sample obtained after the second reaction. The reaction was performed in a minicycler as follows: 2 min at 95°C; followed by 50 cycles of 40 s at 95°C, 40 s at 53°C, and 40 s at 72°C; and a final 5 min at 72°C. Because of the difference in the concentrations of the primers, the reaction yielded predominantly fluorescently labeled single-stranded DNA. The products of the second stages of amplification were analyzed by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels. The products of the third-stage PCR were analyzed in 4% agarose gels.

Sequencing.

The fragment of the pol gene that determines resistance to PIs obtained in the second-stage PCR was subjected to automated dideoxy sequencing with one of the terminal primers, a commercial kit (DyeDeoxy terminator ABI sequencing kit with Taq Polymerase FS; PE Corp.), and an ABI-373A automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Both strands of the target proviral DNA were sequenced by using primers F2249 and R2564. The population sequencing of the PCR products was therefore done. Due to low genetic diversity within the protease encoding region among the samples studied, this sequencing method allowed the accurate identification of the nucleotide sequence, but in one case when a polymorphic nucleotide position was illegible, an N was introduced in the nucleotide sequence.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The derived 249-bp nucleotide sequences of the protease region encoding 10 to 92 amino acids of HIV-1 protease were aligned with reference strains of subtypes A to K from the HIV-1 GenBank (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov). Phylogenetic analysis was performed by the neighbor-joining method, with the nucleotide distance calculated by the Kimura two-parameter approach (21), included in the PHYLIP package (15), with bootstrapping. The nucleotide sequences derived from the samples from HIV-1-infected IDUs in Eastern Europe were also obtained from HIV-1 GenBank by using the BLAST program. A relationship (correlation) between interpatient sequence distances and their sampling years was examined by using the multiple linear regression analysis. A t test was used to compare groups. All statistical calculations were done by using STATISTICA software version 6.0 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, Okla.).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The protease encoding sequences reported in the present study have been assigned GenBank accession numbers AY618594 to AY618620.

HIV-ProteaseChip with immobilized oligonucleotides.

The original oligonucleotide HIV-ProteaseChip was developed to identify mutations (polymorphisms) in HIV-1 group M genome associated with resistance to PIs. The identification procedure was based on the hybridization of a fluorescently labeled amplified fragment of the pol gene with the set of probes immobilized inside three-dimensional hydrogel pads of the microarray.

The method includes four successive steps: (i) isolation of proviral DNA from clinical specimens; (ii) nested PCR amplification to yield fluorescently labeled predominantly single-stranded DNA targets, (iii) hybridization of the labeled product to the chip, and (iv) registration of results by using a specialized analyzer (Biochip-IMB).

The set of immobilized probes included oligonucleotides corresponding to either the wild type (belonging to strain that has no mutations associated with PI resistance) or mutant-type sequences (containing such mutations). Oligonucleotides form corresponding perfect or imperfect duplexes with target DNA; the differences in these structures' stabilities enable one to discriminate between positive and negative hybridization signals by comparing their fluorescence intensities.

If the target DNA has no PI-related mutations and contains a mutation not related to PI resistance (e.g., subtype-specific polymorphisms), it must be complementary to “wild-type” immobilized oligonucleotide except for one mismatch. The same target DNA must form duplexes with two or more mismatches with “mutant-type” oligonucleotides. The differences in such structures' stabilities are still enough for correct decision-making regarding the presence or absence of the drug resistance-related mutations.

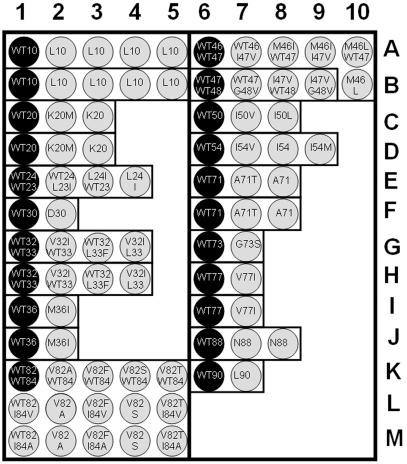

The HIV-ProteaseChip for identification of PI-resistant strains of HIV-1 contains two blocks of 49 and 34 oligonucleotides (see Table 2 and Fig. 3). It can detect 31 of the most common mutations in the protease-coding fragment of the pol gene related to the resistance to the PIs. Gel pads with immobilized oligonucleotides are arrayed in 16 groups (Fig. 3), each group corresponding to a single variable amino acid position. The immobilized oligonucleotide in one gel pad of each group matches the wild-type sequence, i.e., forms a perfect duplex with the wild-type target DNA. Oligonucleotides immobilized in other gel pads of the group form perfect duplexes with different mutant variants of the same codon. Oligonucleotides were immobilized through their 3′ ends as described previously (30). Oligonucleotides for hybridization analysis and prehybridization PCR primers were designed by using Oligo 6 software (Molecular Biology Insights, Cascade, Colo.).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in the HIV-ProteaseChip for identification of drug-resistant mutations in the protease gene of HIV-1

| Code | Amino acid position(s) | Amino acid substitutiona | Nucleotide substitution(s) | Sequence (5′→3′) | Subtype origin of sequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 10 | Leu(WT) | CTC | CGACCCCTCGTCACA | B |

| A2 | 10 | L10F | TTC | CGACCCTTCGTCACA | B |

| A3 | 10 | L10I | ATC | CGACCCATCGTCACA | B |

| A4 | 10 | L10R | CGC | GACCCCGCGTCACA | B |

| A5 | 10 | L10V | GTC | CGACCCGTCGTCACA | B |

| B1 | 10 | Leu(WT) | CTT | CGACCCCTTGTCACA | A |

| B2 | 10 | L10F | TTT | CGACCCTTTGTCACA | A |

| B3 | 10 | L10I | ATT | CGACCCATTGTCACA | A |

| B4 | 10 | L10R | CGT | GACCCCGTGTCACA | A |

| B5 | 10 | L10V | GTT | CGACCCGTTGTCACA | A |

| C1 | 20 | Lys(WT) | AAG | GCAACTAAAGGAAGCTCT | B |

| C2 | 20 | K20M | ATG | GCAACTAATGGAAGCTCT | B |

| C3 | 20 | K20R | AGG | GCAACTAAGGGAAGCTC | B |

| D1 | 20 | Lys(WT) | AAA | ACAGCTAAAAGAAGCTCT | A |

| D2 | 20 | K20M | ATA | ACAGCTAATAGAAGCTCT | A |

| D3 | 20 | K20R | AGA | ACAGCTAAGAGAAGCTC | A |

| E1 | 23/24 | Leu(WT)/Leu(WT) | CTA/TTA | AGCTCTATTAGATACAGGA | B |

| E2 | 23/24 | L23I/WT24 | ATA/TTA | AGCTATATTAGATACAGGA | B |

| E3 | 23/24 | WT23/L24I | CTA/ATA | AGCTCTAATAGATACAGGA | B |

| E4 | 23/24 | L23I/L24I | ATA/ATA | AGCTATAATAGATACAGGA | B |

| F1 | 30 | Asp(WT) | GAT | TACAGGAGCAGATGATACA | B |

| F2 | 30 | D30N | AAT | TACAGGAGCAGATAATACA | B |

| G1 | 32/33 | Val(WT)/Leu(WT) | GTA/TTA | TGATACAGTATTAGAAGAAATG | B |

| G2 | 32/33 | V32I/WT33 | ATA/TTA | TGATACAATATTAGAAGAAATG | B |

| G3 | 32/33 | WT32/L33F | GTA/TTC | TGATACAGTATTCGAAGAAA | B |

| G4 | 32/33 | V32/L33F | ATA/TTC | TGATACAATATTCGAAGAAA | B |

| H1 | 32/33 | Val(WT)/Leu(WT) | GTA/TTA | TGATAC (A/G) GTATTAGAAGACATG | A |

| H2 | 32/33 | V321/WT33 | ATA/TTA | TGATAC (A/G) ATATTAGAAGACATG | A |

| H3 | 32/33 | WT32/L33F | GTA/TTC | TGATAC (A/G) GTATTCGAAGACA | A |

| H4 | 32/33 | V32/L33F | ATA/TTC | TGATAC (A/G) ATATTCGAAGACA | A |

| I1 | 36 | Met(WT) | ATG | AAGAAATGAGTTTGCCA | B |

| I2 | 36 | M361 | ATA | AAGAAATAAGTTTGCCAG | B |

| J1 | 36 | Met(WT) | ATG | AAGACATGAATTTGCCA | A |

| J2 | 36 | M36I | ATA | AAGACATAAATTTGCCAG | A |

| K1 | 82/84 | Val(WT)/I(WT) | GTC/ATA | ACA (C/A) CTGTCAACATAATTG | B |

| K2 | 82/84 | V82A/WT84 | GCC/ATA | ACA (C/A) CTGCCAACATAATTG | B |

| K3 | 82/84 | V82F/WT84 | TTC/ATA | ACA (C/A) CTTTCAACATAATTG | B |

| K4 | 82/84 | V82S/WT84 | TCC/ATA | ACA (C/A) CTTCCAACATAATTG | B |

| K5 | 82/84 | V82T/WT84 | ACC/ATA | ACA (C/A) CTACCAACATAATTG | B |

| L1 | 82/84 | WT82/I84V | GTC/GTA | ACA (C/A) CTGTCAACGTAATTG | B |

| L2 | 82/84 | V82A/I84V | GCC/GTA | ACA (C/A) CTGCCAACGTAATTG | B |

| L3 | 82/84 | V82F/I84V | TTC/GTA | ACA (C/A) CTTTCAACGTAATTG | B |

| L4 | 82/84 | V82S/I84V | TCC/GTA | ACA (C/A) CTTCCAACGTAATTG | B |

| L5 | 82/84 | V82T/I84V | ACC/GTA | ACA (C/A) CTACCAACGTAATTG | B |

| M1 | 82/84 | WT82/I84A | GTC/GCA | ACA (C/A) CTGTCAACGCAATTG | B |

| M2 | 82/84 | V82A/I84A | GCC/GCA | ACA (C/A) CTGCCAACGCAATTG | B |

| M3 | 82/84 | V82F/I84A | TTC/GCA | ACA (C/A) CTTTCAACGCAATTG | B |

| M4 | 82/84 | V82S/I84A | TCC/GCA | ACA (C/A) CTTCCAACGCAATTG | B |

| M5 | 82/84 | V82T/I84A | ACC/GCA | ACA (C/A) CTACCAACGCAATTG | B |

| A6 | 46/47 | Met(WT)/Ile(WT) | ATG/ATA | AAACCAAAAATGATAGGG | B |

| A7 | 46/47 | WT46/I47V | ATG/GTA | AACCAAAAATGGTAGGG | B |

| A8 | 46/47 | M461/WT47 | ATA/ATA | GAAACCAAAAATAATAGGG | B |

| A9 | 46/47 | M461/I47V | ATA/GTA | GAAACCAAAAATAGTAGGG | B |

| A10 | 46/47 | M46L/WT47 | TTG/ATA | AAACCAAAATTGATAGGG | B |

| B10 | 46/47 | M46L/I47V | TTA/GTA | GAAACCAAAATTAGTAGGG | B |

| B6 | 47/48 | IIe(WT)/Gly(WT) | ATA/GGG | AAATGATAGGGGGAATT | B |

| B7 | 47/48 | WT47/G48V | ATA/GTG | AAATGATAGTGGGAATTG | B |

| B8 | 47/48 | I47V/WT48 | GTA/GGG | AAATGGTAGGGGGAAT | B |

| B9 | 47/48 | I47V/G48V | GTA/GTG | AAATGGTAGTGGGAATTG | B |

| C6 | 50 | IIe(WT) | ATT | GGGGGAATTGGAGGT | B |

| C7 | 50 | I50V | GTT | GGGGGAGTTGGAGGT | B |

| C8 | 50 | I50L | CTT | GGGGGACTTGGAGGT | B |

| D6 | 54 | IIe(WT) | ATC | GAGGTTTTATCAAGGTAAGA | A |

| D7 | 54 | I54V | GTC | GAGGTTTTGTCAAGGTAAG | A |

| D8 | 54 | I54L | CTC | GAGGTTTTCTCAAGGTAAGA | A |

| D9 | 54 | I54M | ATG | GAGGTTTTATGAAGGTAAGA | A |

| E6 | 71 | Ala(WT) | GCT | GGACATAAAGCTATAGGTAC | B |

| E7 | 71 | A71T | ACT | GGACATAAAACTATAGGTACA | B |

| E8 | 71 | A71V | GTT | GGACATAAAGTTATAGGTACA | B |

| F6 | 71 | Ala(WT) | GCT | GGAAAAAAGGCTATAGGTAC | A |

| F7 | 71 | A71T | ACT | GGAAAAAAGACTATAGGTACA | A |

| F8 | 71 | A71V | GTT | GGAAAAAAGGTTATAGGTACA | A |

| G6 | 73 | Gly(WT) | GGT | AAAGCTATAGGTACAGTATTA | B |

| G7 | 73 | G73S | AGT | AAAGCTATAAGTACAGTATTA | B |

| H6 | 77 | Val(WT) | GTA | ACAGTATTAGTAGGACCTACAC | B |

| H7 | 77 | V771 | ATA | ACAGTATTAATAGGACCTACAC | B |

| I6 | 77 | Val(WT) | GTA | ACGGTATTAGTAGG (A/G) CCTACCC | A |

| I7 | 77 | V771 | ATA | ACGGTATTAATAGG (A/G) CCTACCC | A |

| J6 | 88 | Asn(WT) | AAT | ATTGGAAGAAATCTGTTG | B |

| J7 | 88 | N88D | GAT | ATTGGAAGAGATCTGTTG | B |

| J8 | 88 | N88S | AGT | ATTGGAAGAAGTCTGTTG | B |

| K6 | 90 | Leu(WT) | TTG | AGAAATCTGTTGACTCAGAT | B |

| K7 | 90 | L90M | ATG | AGAAATCTGATGACTCAGAT | B |

WT, wild type.

FIG. 3.

Scheme of HIV-ProteaseChip. The darkly shaded pads contain oligonucleotides corresponding to the wild-type sequence. The lightly shaded pads contain the mutant oligonucleotide probes.

The selection of the specific immobilized probe sequences was based on the sense strand of the pol gene of the HXB2 strain and the multiple alignment of the sequences of HIV-1 isolates obtained from IDUs in the former Soviet Union republics; these sequences have been published (RU98001, 98UA0116, 98BY10443, and KAL153 [GenBank accession numbers AF193277, AF413987, AF414006, and AF193276, respectively]). The procedure included two main steps. First, melting temperatures for perfect matches were determined for prospective oligonucleotides. Second, the length of the oligonucleotides was adjusted to maintain the range of melting temperatures within 3 to 4°C for hybridization probes.

Hybridization on the HIV-ProteaseChip.

A hybridization mixture was prepared by adding 10 μl of the third-stage asymmetric PCR mixture to 20 μl of a solution containing 1.5 M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.15 M HEPES (pH 7.5), and 15 mM EDTA. The hybridization mixture was loaded into a hybridization chamber (Biochip-IMB) that formed a 30-μl closed space over the chip and was then incubated for 18 h at 20°C. After hybridization, the chip was washed three times at room temperature with 6.67× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7]) buffer (pH 7.4) containing 10% Tween 20 and then air dried.

The optimal guanidine thiocyanate concentration, temperature, and time of hybridization were determined by analyzing the melting curves and hybridization kinetics of perfect duplexes for all available samples. The melting curves were built by using data obtained on a microchip under near-equilibrium conditions as described earlier (12, 29).

Fluorescence measurements.

The resulting fluorescence pattern was recorded by using either a research-grade charge-coupled device camera-equipped microscope as described earlier in cases where Texas red labeling was used or a portable fluorescence analyzer when cyanine dye was used. The data collection and processing were performed with dedicated software (Biochip-IMB).

RESULTS

Nucleotide sequence data.

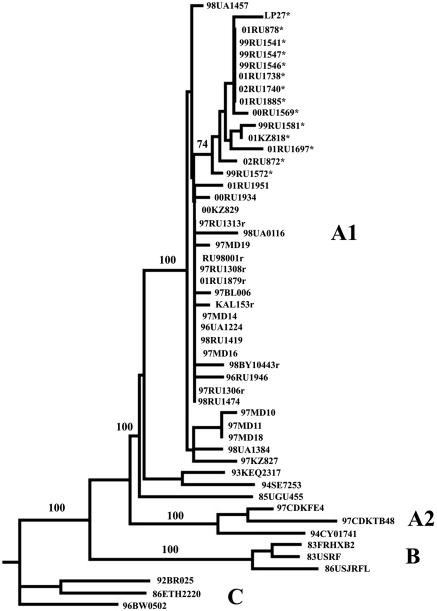

Figure 1 shows a neighbor-joining tree of the protease encoding sequences. As expected, all 27 sequences belonged to the HIV-1 genetic subtype A (A1) and clustered with the nucleotide sequences from the HIV-1 GenBank previously derived from IDUs in Russia, the Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova (25, 26, 28, 34). The clustering with subtype A was also observed for the nucleotide sequences 97RU1306, 97RU1308, 97RU1313, and 01RU879 derived from individuals infected with the circulating recombinant form CRF03_AB, as well as for the CRF03_AB variants CRF03_AB KAL153, RU98001, and 98BY10443 published previously (25, 26). Interestingly, isolate LP27, derived in 2001 in Spain from a migrant from the former Soviet Union (18), also clustered together with the Eastern European sequences.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Eastern European subtype A nucleotide sequences encoding protease. Horizontal lines indicate nucleotide difference between sequences; vertical spacing is for clarity only. The bootstrap value (of 100 replicates) supporting a particular cluster is placed next to the nodes. The Kaliningrad CRF03_AB recombinant sequences are marked with an “r.” Nucleotide sequences bearing the V77I substitution are marked with asterisks. Phylogenetic relationships were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The Eastern European nucleotide sequences from the Ukraine (98UA0116), Belarus (97BL006 and BY10443), Russia (RU98001 and KAL153), Moldova (97MD10 to -19), and Spain (LP27) published previously (GenBank accession numbers AF413987, AF193275, AF414006, AF193277, AF193276, AF400675 to AF400680, and AF455622, respectively) (18, 25, 26, 28, 34), as well as the representative sequences of genetic subtypes A1, A2, B, and C from the Los Alamos database, were also included in the analysis.

The mean genetic diversity of 27 HIV-1 genetic subtype A IDU sequences encoding protease was 1.38 ± 0.79 (range, 0.00 to 3.23). This figure is slightly lower than the mean genetic diversity for the V3 GP120 encoding region found previously for these HIV-1 genetic variants (2.41 ± 1.85, range 0.00 to 6.19). The ratio between synonymous and nonsynonymous differences (ds/dn ratio) calculated by the SNAP program (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov) for this set of 27 sequences was 5.10, showing the low evolutional pressure on this genomic region in untreated patients. The genetic variability within the sequences from different geographic regions varied slightly. For example, the mean nucleotide sequence diversity from 1996 to 1998 in the Ukraine was 1.01 ± 0.61 (range, 0.40 to 1.60) and significantly lower (R = 0.673, R2 = 0.453, P = 0.017) than for the nucleotide sequence sets found in 2000 and 2001 in Moscow (1.47 ± 0.49 [range, 0.80 to 2.01]) and in 1997 and 2000 in Kazakhstan (2.14 ± 0.23 [range, 2.01 to 2.41]). It is interesting that we have not observed any variability in the protease-encoding region among the sequences (n = 4) derived from individuals infected with the circulating recombinant form CRF03_AB. These sequences were obtained from epidemiologically unlinked patients in Kaliningrad, Perm, and Yekaterinburg. It could be suggested that such homogeneity is related to the recombinant nature of the genome of this virus. Combination in one virus of the Gag precursor and the protease belonging to subtype A and the revertase and the integrase of subtype B can impose the high restriction on the genetic diversity in both regions of CRF03_AB genome. However, such homogeneity may also be a result of the relatively low number of nucleotide sequences in the set studied.

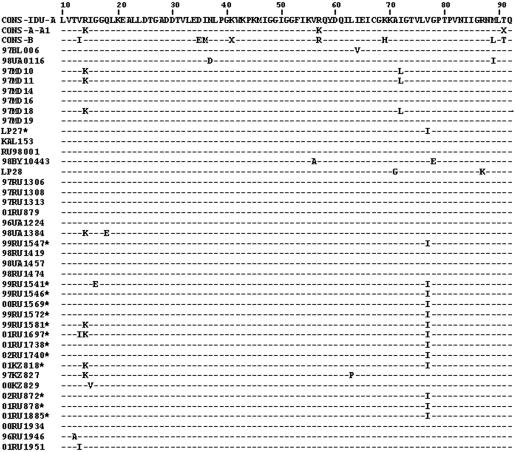

Amino acid sequence data.

The amino acid sequence of each strain was aligned with the protease subtype A consensus sequence. The amino acid sequences previously derived from IDUs infected with the Russian subtype A variant or the CRF03_AB recombinant form were also included in the analysis. The alignment is shown in Fig. 2. This analysis revealed no amino acid diversity in the region from amino acids 19 to 62 and from amino acids 78 to 92, including the sequences around the active site (amino acids 21 to 33), the top of the flap (amino acids 47 to 56), and the second loop of the β sheet (amino acids 78 to 88).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of amino acid sequences deduced from the HIV-1 subtype A protease gene. The protease sequences from IDUs are aligned with the subtype A consensus sequence derived from IDUs previously. The subtype A1 consensus and subtype B consensus from the Los Alamos database, as well as the subtype A IDU protease sequences published previously, were also included in the alignment.

We have not observed any primary protease resistance-associated mutations (20M; 24I and 30N; 48V; 50V; 82A 82F, or 82T; 84V; 90M) among the 27 sequences studied. At the same time, eight secondary mutations noted in the HIV-1 drug resistance mutations database (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov) were found in the set of sequences studied. However, at least five of eight substitutions characterized as “secondary protease mutations” in subtype B (D35E, M36I, R41K, H69K, and L89M) were observed in >90% of all known amino acid protease sequences derived from HIV-1 variants belonging to genetic subtype A (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov). These changes appear to be characteristic for the subtype A and to reflect intersubtype genetic polymorphisms in the HIV-1 protease gene. These substitutions were also observed in all 27 IDU subtype A sequences in the present study.

Substitutions G16E and L63P found in RU541 and KZ827, respectively, were also described earlier (10). However, these mutations were identified in HIV-1 isolates derived from PI-treated individuals, which, in comparison to the background, bear a great number of mutations (up to 12) in the pro gene simultaneously. Altogether, they increase the level of drug resistance and, probably, improve viral fitness. However, the substitutions G16E and L63P by themselves do not seem to increase significantly the level of drug resistance or replicative capacity of the viruses (10).

V77I mutation.

Of particular interest is the mutation V77I found in 13 of 23 (56.5%) amino acid sequences belonging to genetic subtype A (Fig. 2). It was shown previously that this substitution is a secondary mutation frequently found in combination with the mutation D30N determining resistance to nelfinavir in subtype B isolates (36). However, the cause of selection of the V77I substitution is still unclear. It was suggested that V77I might increase the level of replicative capacity of virus bearing the primary nelfinavir resistance mutation D30N. However, the increase in V77I frequency in nelfinavir-treated persons in comparison to the background was not significant (36). Primarily, this was due to high frequency of the V77I mutation in drug-naive populations infected with HIV-1 genetic subtype B variants (13 to 30%) demonstrated in the United States, Belgium, and Australia (2, 36, 40). This mutation was also observed in 13% untreated individuals infected with non-B HIV-1 variants (mostly the circulating recombinant form CRF02_AG) in Cameroon (16). Moreover, other authors studying secondary PI resistance-associated mutations in HIV-1 protease sequences of different group M subtypes infecting drug-naive villagers in Cameroon found the V77I mutation in 7, 13, 25, and 71% of samples belonging to subtypes A, D, F2, and J, respectively (22). These data suggested that V77I might reflect a viral genetic polymorphism, one not directly related to specific selection of nelfinavir resistance variants. An extremely high rate of the V77I mutation (93%) was demonstrated among hemophilia patients infected with HIV-1 subtype B′ variant through contaminated blood products in Shanghai, Peoples Republic of China (47). However, most of these subjects were probably infected from the same source, and these data suggest that the V77I mutation may be easily transmitted via the parenteral route.

On the other hand, in patients on their first nelfinavir-based HAART combination for >6 months with an HIV-1 viral load in plasma of >1,000 copies/ml, the substitution V77I was significantly increased (up to 56.3%) compared to the group of patients with a stable viral load of <50 copies/ml (44). Resch et al. also showed that the V77I substitution may partially compensate in vitro, decreasing the viral infectivity, replicative capacity, and level of virus production caused by another primary nelfinavir resistance mutation at position 88 (38).

The substitution V77I was found in more than half (13 of 23 [56.5%]) subtype A nucleotide sequences derived from HIV-1-infected individuals in 1996 to 2002 in the territory of the former Soviet Union. The first appearance of the V77I substitution in the set studied was associated with patient 99RU1541 (Table 1). 99RU1541 was found to be HIV-1 positive on 4 June 1999 in the Lysva, Perm, region; his blood was sampled for PCR and sequence analysis on 29 September 1999. Later, this substitution was found in two samples derived from HIV-1-infected subjects in Irkutsk in 1999 and in four samples from Moscow taken in 2000 and 2001. Moreover, the V77I mutation was found in seven of eight (87.5%) blood samples taken independently in 2001 and 2002 in Russia and Kazakhstan; this HIV-1 genetic variant bearing the V77I mutation appears to be spreading rapidly among IDUs in the territory of the former Soviet Union.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of V771 mutation between 27 pro subtype A nucleotide sequences derived from IDUs in former Soviet Union cities or regions

| City or geographical region | HIV-1 isolate(s)a and yr of diagnosis (first positive HIV-1 Western blot):

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |

| Ukraine | 96UA1224 | 98UA1384 and 98UA1457 | |||||

| Sakhalin region | 96RU1946 | ||||||

| Karaganda, Kazakhstan | 97KZ827 | 00KZ829 | |||||

| Tyumen region | 98RU1419 | 00RU1934 | |||||

| Irkutsk | 99RU1546* and 99RU1547* | ||||||

| Lysva, Perm region | 99RU1541* | ||||||

| Moscow | 99RU1581* and 99RU1572* | 00RU1569* | 01RU1697* | ||||

| Pavlodar, Kazakhstan | 01KZ818* | ||||||

| Perm | 98RU1474 | 01RU1738* | 02RU1740* | ||||

| Gornozavodsk, Perm region | 01RU1951 | ||||||

| Khabarovsk Kray | 01RU1885* | ||||||

| Yekarerinburg | 01RU878* | 02RU872* | |||||

HIV-1 isolates bearing the V771 substitution within the protease encoding region are indicated by asterisks.

Study of the V77I distribution by using HIV-ProteaseChip.

In the initial stage of analysis, DNA samples derived from 27 HIV-positive patients in different regions of Russia were hybridized with the HIV-ProteaseChip (Table 2). The results of sequencing and microarray analysis were in full accordance.

We then analyzed 92 additional clinical specimens derived from HIV-1-infected IDUs in Russia, the Ukraine, and Kazakhstan by the microarray technique (Table 3). We found that the earliest detection of the V77I variant could be dated to the beginning of 1997. The V77I HIV-1 variant was found in all five samples from the Tver region obtained in March to July 1997 (Table 3). The V77I HIV-1 variant appears to have been introduced into or emerged within the Russian IDU population in Tver at the end of 1996 or the beginning of 1997. Further observations confirm this suggestion. First, we have not observed this mutation in any of 11 samples obtained earlier in 1996. Second, the V77I mutation is absent in all variants of the CRF03_AB, which emerged in the Kaliningrad region in 1996. Third, the V77I substitution was not observed in any of nine Ukrainian samples obtained from 1996 to 1998. Moreover, it was not found in the Karaganda outbreak in Kazakhstan in 1997. In contrast, V77I was identified in Kazakhstan later, i.e., in 2001. The HIV-1 epidemic in the Pavlodar region, Kazakhstan, where it was found, started later, in 1999 (48), and this outbreak can thus be associated with the Russian HIV-1 IDU epidemic. Finally, the V77I substitution was absent in all subtype A or CRF03_AB nucleotide sequences from GenBank derived from IDUs in Belarus, Moldova, and the Ukraine from 1997 to 1998. Thus, the V77I variant most likely emerged in Russia, probably in the Tver region, although other regions cannot be excluded.

TABLE 3.

Distributions of the V77I mutations by city or geographical region and year of the first HIV-1-positive Western blot

| City or geographical region | No. and type of HIV-1 infections at yr of diagnosis (first positive HIV-1 Western blot)a:

|

Total no. of HIV-1 isolates

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | WT | V77I | |

| Ukraine | 3 WT | 2 WT | 4 WT | 9 | |||||

| Krasnodar Kray | 4 WT | 4 | |||||||

| Saratov region | 7 WT | 7 | |||||||

| Sakhalin region | 1 WT | 1 | |||||||

| Moldova | 1 WT | 1 WT | 2 | ||||||

| Rostov-on-Don | 3 WT | 3 | |||||||

| Karaganda, Kazakhstan | 2 WT | 2 WT | 3 WT | 7 | |||||

| Tver region | 5 V77I | 3 V77I | 8 | ||||||

| Moscow | 2 WT | 1 WT, 5 V77I | 3 WT, 5 V77I | 1 WT, 8 V77I | 1 V77I | 7 | 19 | ||

| Perm | 6 WT | 4 WT | 2 V77I | 1 V77I | 1 V77I | 10 | 4 | ||

| Tyumen region | 1 WT | 1 WT | 2 | ||||||

| Lysva, Perm region | 1 V77I | 4 V77I | 5 | ||||||

| Irkutsk | 7 V77I | 7 | |||||||

| Pavlodar, Kazakhstan | 1 V77I | 5 V77I | 6 | ||||||

| Yekaterinburg | 1 V77I | 1 WT, 3 V77I | 1 V77I | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Gomozavodsk, Perm region | 7 WT | 7 | |||||||

| Khabarovsk Kray | 1 V77I | 1 | |||||||

The results of protease genotyping using sequencing and/or microchip assay are shown. WT, HIV-1 wild-type isolates (V in position 77); V77I, HIV-1 isolates bearing the V77I substitution.

It is interesting that all pro nucleotide sequences containing the V77I substitution clustered together on the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). Although such clustering is not significant (bootstrap value of 74), these viruses may have originated from a common source. In contrast, we have not observed specific clustering when 48 env C2-V3 256-bp sequences derived from the same samples previously were studied (data not shown), but this may be due to a higher genetic diversity in the C2-V3 env region. The fact that the mean interpatient genetic variability between the nucleotide sequences bearing the V77I substitution was 0.71 ± 0.66 also supports the “common source” hypothesis. At the same time, the interpatient genetic difference between the V77I pro nucleotide sequences and the wild-type pro nucleotide sequences was significantly higher (1.91 ± 0.56 [P < 0.01]). Finally, the nonsynonymous V77I substitution is accompanied by two synonymous changes characteristic for this group of virus isolates. These are the ACA→ACG substitution in the triplet Thr-31 and the GGA→GGG substitution in the triplet Gly-78 observed among 11 (84.6%) and 12 (92.3%) of 13 the V77I pro nucleotide sequences, respectively. Moreover, these changes were absent in all pro wild-type nucleotide sequences from the set studied (n = 10) and in the nucleotide sequences derived from all East-European IDUs HIV-1 variants belonging to genetic subtype A submitted to GenBank previously (n = 8). Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that the V77I HIV-1 variant with two additional characteristic synonymous substitutions at positions 31 and 78 emerged in the IDU population at the end of 1996 or the beginning of 1997 and then spread rapidly through the territory of the Russian Federation (Fig. 4). This strain later caused the HIV-1 outbreaks in Moscow, Irkutsk, and Yekaterinburg. When the clinical specimens dated after 1999 were studied, the V77I variant was absent only in Tyumen and Gornozavodsk of the Perm region. It is possible that the HIV-1 outbreaks in these cities were epidemiologically linked to the regions, where the V77I was still not found (for example, to the Ukraine).

FIG. 4.

Geographic distribution of the V77I subtype A HIV-1 IDU variant, as well as a wild-type subtype A IDU strain, in the former Soviet Union from 1997 to 2003. Assignments are based upon analysis of several independent cases from each region (Tables 1 and 3).

Transmission of the V77I mutation.

In order to demonstrate possible transmission of both the wild type and the V77I mutant HIV-1 variants, HIV-ProteaseChip was also used to analyze 12 additional samples derived from epidemiologically linked HIV-1-positive subjects infected via different routes of transmission (Table 4). The results demonstrate that in all four cases the genotype of the donor and the recipients was the same, irrespective of the route of transmission. Moreover, sequence analysis revealed that all samples derived from the individuals infected with the V77I variant bear the same signature substitutions in the triplets 31 and 78. This finding supports the transmission of the V77I mutant variant. Interestingly, the V77I mutation was found in both samples derived from 98RU1423 sequentially with the 13 months time lapse. Possible selection of these substitutions soon after transmission under the host pressure cannot be fully excluded. However, rapid transmission of the V77I mutant variant is most likely to occur, as evidenced by the high prevalence of this variant within IDU populations where HIV-1 spread rapidly, presumably from a single source (Irkutsk, Lysva, and Saratov) (Table 3).

TABLE 4.

Possible transmission of the wild type and the V77I HIV-1 variants via different routesa

| Index case

|

Route of transmission | Recipient

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Genotype | Date of first positive test | Date of blood draw | Individual | Genotype | Date of first positive test | Date of blood draw | |

| 97UA1426 | WT | 31.12.97 | 24.08.98 | Parenteral, injecting drug usage | 98RU1421 | WT | 14.07.98 | 21.08.98 |

| 98RU1382 | WT | 12.02.98 | 25.02.98 | |||||

| 98RU1383 | WT | 25.02.98 | 02.03.98 | |||||

| 98RU1390 | WT | 06.03.98 | 11.03.98 | |||||

| 98RU1423 | WT | 08.05.98 | 24.08.98 | |||||

| WT | 30.09.99 | |||||||

| 98UA1384 | WT | 28.02.98 | 17.03.98 | Sexual, from man to woman | 99RU1481 | WT | 25.02.98 | 12.02.99 |

| 02RU1738 | V77I | 24.10.01 | 11.03.02 | Parenteral, blood transfusion | 02RU1742 | V77I | 15.01.02 | 11.03.02 |

| 98RU1471 | V77I | 13.11.98 | 02.11.98 | Parenteral, injecting drug usage | RU1496 | V77I | 27.05.99 | 28.05.99 |

| RU1500 | V77I | 26.04.00 | 11.05.99 | |||||

| RU1501 | V77I | 25.05.99 | 28.05.99 | |||||

| RU1503 | V77I | 20.04.99 | 11.05.99 | |||||

| RU1544 | V77I | 07.05.99 | 04.06.99 | |||||

The results of genotyping of samples derived from pairs (clusters) of epidemiologically linked individuals are presented. WT, wild type; V77I, substitution in triplet 77. In the case of RU1423, two sequentially taken samples were analyzed. Dates are given as “day.month.year.”

DISCUSSION

To characterize polymorphisms of the subtype A protease in the former Soviet Union, the pro region obtained from HIV-1-positive untreated IDUs was analyzed by using sequencing and a novel HIV-ProteaseChip hybridization technology. Oligonucleotide microarrays have already been proven to be a powerful diagnostic tool for identifying genetic polymorphisms (24, 29, 41). Moreover, several approaches based on hybridization technology have already been described for genotypic analysis of HIV-1 drug resistance (42, 43). However, the specificity and sensitivity of hybridization technology is controlled by a dedicate probe-target annealing interaction. This means that unexpected mutations in the target sequence region may cause false results, and standard hybridization may not be a suitable strategy to apply to genes with high rates of genetic polymorphism. It was previously shown that the commercial HIV PRT GeneChip assay (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, Calif.) and the HIV-1 RT Line Probe Assay (Innogenetics, Alpharetta, Ga.) demonstrated >90% concordance over the 40 codons tested in the RT and protease genes. Mutations that were discordant between the assays mainly comprised natural polymorphisms (46). In the present study, the genetic diversity in the pro gene region was found to be extremely low. We have not observed more than two substitutions in the regions, which are complementary to the oligonucleotide probe I6 and I7 (Fig. 3 and Table 5). Low genetic diversity can be due to (i) low evolutionary pressure on this region of HIV-1 genome among drug-naive patients or (ii) short time lapse between possible date of infection and the date of blood taking (5.7 ± 7.8 and 8.0 ± 6.2 months for individuals infected with wild-type virus and the V77I mutant variant, respectively [range, 0 to 22 months]). However, more experiments are necessary to decide whether the use of the HIV-ProteaseChip for identification of PIs resistant mutations is suitable in populations characterized by higher levels of genetic diversity. The possibility of this test identifying potentially clinically relevant mutations present in the nonpredominant viral quasispecies also needs to be investigated in detail. However, the microarray technique described here can be useful tool for tracing signature mutations in different geographic regions and risk groups.

TABLE 5.

Genetic diversity found in the pro gene region complementary to the oligonucleotides I6 and I7 used for detection of the subtype A V77I mutationa

| HIV-1 isolate | Oligonucleotide I6 | Oligonucleotide I7 | Reactivity with I6/I7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACGGTATTAGTAGGRCCTACCC | ACGGTATTAATAGGRCCTACCC | ||

| 97RU1306 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 97RU1308 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 97RU1313 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 01RU1879 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 96UA1224 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 98UA1384 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 99RU1547* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 98RU1419 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 98UA1457 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 98RU1474 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 99RU1541* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 99RU1546* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 00RU1569* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 99RU1572* | ---------A----A------- | --------------A------- | −/+ |

| 99RU1581* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 01RU1697* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 01RU1738* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 02RU1740* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 01KZ818* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 97KZ827 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 00KZ829 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 02RU872* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 01RU878* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 01RU1885* | ---------A----G------- | --------------G------- | −/+ |

| 00RU1934 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 96RU1946 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

| 01RU1951 | --------------A------- | ---------G----A------- | +/− |

The 22-bp fragment of the pro nucleotide sequences derived from 27 HIV-1-positive individuals are aligned to the I6 and I7 oligonucleotides used to detect the V77I mutation. Both I6 and I7 contained mixtures of two oligonucleotides bearing a G or an A in position 15 (triplet 78), which is marked with an “R.” HIV-1 isolates bearing the V77I substitution are marked with asterisks. The triplet 77 is underlined.

The data presented raise at least two questions. First, did the V77I HIV-1 variant emerge spontaneously or was its origin associated with the start of the use of PIs in Russia? Nelfinavir is produced by Agouron Pharmaceuticals, and this PI is distributed in Russia by Hoffman-La Roche under the commercial name Virasept. The first use of nelfinavir in Russia is dated to 1998. Since the first detection of V77I in Tver was in 1997, the variant most probably emerged in the IDU population spontaneously.

The second question is of greater importance. What were the factors that caused such rapid transmission of the V77I HIV-1 strain among IDUs in Russia? Up to 1 January 1997, there were only 2,607 HIV-1-infected individuals officially registered in the Russian Federation, for which injecting drug usage was the main risk factor for HIV transmission in ca. 50%. The HIV-1 epidemic in the Tver region at the beginning of 1997, along with the Kaliningrad outbreak, which started at approximately the same time, and the HIV-1 outbreaks in Krasnodar Kray and the Rostov-on-Don region recognized in 1996 led to a dramatic increase in IDU-transmitted cases. The rapid spread of the V77I variant may be associated with epidemiological factors, such as transmission of the newly emergent HIV-1 strain (possibly from Tver) to the large industrial regions of the Russian Federation (to Moscow and the Moscow region, later to the Urals and Eastern Siberia), where tens of thousands of IDUs were then infected with HIV-1 from the same source due to the use of nonsterile equipment during the preparation or use of injected drugs (Fig. 4).

On the other hand, distribution of the V77I variant took place when the wild-type virus had been already widely distributed among IDUs, at least in some regions of the former Soviet Union, including the Ukraine, Moldova, and South Russia. It is therefore possible that this strain has some biological advantages over the wild-type virus that favor its rapid spread among IDUs. We did not observe any significant biological differences between the V77I variant and the wild-type virus. Both viruses use the same spectrum of secondary receptors; these are dualtropic and have low syncytium-forming activity (data not shown). The isolates studied also had indistinguishable rates of replication in donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells. However, at the population level, such virus properties as stability in different environments (for example, in the solution of illicit drugs used for injection) or dose necessary for infection through the parenteral route of transmission may be of great epidemiological importance. It also cannot be excluded that genomic changes leading to fitness advantages of the V77I strain over the wild-type virus may be situated in other part(s) of viral genome. In this case, the V77I substitution, as well as two other synonymous mutations in the pro gene, may be just a part of the beneficial haplotype.

We thus describe here a new molecular-epidemiological marker that can be a useful tool for studying the HIV-1 epidemic in Eastern Europe. Testing this mutation in the genomes of newly identified HIV-1 isolates may help to establish the origin of the virus that caused any local HIV-1 epidemic. Second, our data show that a new HIV-1 subtype A variant bearing a secondary nelfinavir resistance mutation is spreading rapidly among IDUs and their sexual partners in Russia. Nelfinavir is one of the most widely used antiretroviral drugs, and this fact must be taken into account when HAART schemes at the regional level are developed, as well as for particular HIV-1-infected individuals. The data published previously showed that the preexistence of secondary mutations in the protease genetic background may have implications in HIV-1 fitness evolution and virologic response to antiretroviral therapy (39, 45).

Finally, the V77I variant may have some biological advantages affecting parenteral transmission. We can thus suggest that in 1997 the HIV-1 epidemic in Russia entered a new phase characterized by appearance of a new IDU subtype A HIV-1 variant, which is possibly better adapted to the corresponding ecological niche. Such rapid selection of a particular HIV-1 variant within the population infected from a single source has not previously been reported, and it is not known whether the scenario occurring in Russia is unique. However, the possibility of the worldwide appearance of new HIV-1 variants characterized by advantages in terms of transmission or fitness is highly probable. The molecular epidemiological and virological monitoring of HIV-1 worldwide thus continues to be of great importance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammaranond, P., P. Cunningham, R. Oelrichs, K. Suzuki, C. Harris, L. Leas, A. Grulich, D. A. Cooper, and A. D. Kelleher. 2003. Rates of transmission of antiretroviral drug resistant strains of HIV-1. J. Clin. Virol. 26:153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammaranond, P., P. Cunningham, R. Oelrichs, K. Suzuki, C. Harris, L. Leas, A. Grulich, D. A. Cooper, and A. D. Kelleher. 2003. No increase in protease resistance and a decrease in reverse transcriptase resistance mutations in primary HIV-1 infection: 1992-2001. AIDS 17:264-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balode, D., A. Ferdats, I. Dievberna, L. Viksina, L. Rozentale, T. Kolupajeva, T. Konicheva, and T. Leitner. 2004. Rapid epidemic spread of HIV type 1 subtype A1 among intravenous drug users in Latvia and slower spread of subtype B among other risk groups. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 20:245-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bobkov, A., R. Cheingsong-Popov, L. Selimova, N. Ladnaya, E. Kazennova, A. Kravchenko, E. Fedotov, S. Saukhat, S. Zverev, V. Pokrovsky, and J. Weber. 1997. An HIV type 1 epidemic among injecting drug users in the former Soviet Union caused by a homogeneous subtype A strain. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:1195-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobkov, A., E. Kazennova, L. Selimova, M. Bobkova, T. Khanina, N. Ladnaya, A. Kravchenko, V. Pokrovsky, R. Cheingsong-Popov, and J. Weber. 1998. A sudden epidemic of HIV type 1 among injecting drug users in the former Soviet Union: identification of the subtype A, subtype B, and novel gagA/envB recombinants. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:669-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bobkov, A. F., E. V. Kazennova, T. A. Khanina, M. R. Bobkova, L. M. Selimova, A. V. Kravchenko, V. V. Pokrovsky, and J. N. Weber. 2001. An HIV type I subtype A strain of low genetic diversity continues to spread among injecting drug users in Russia: study of the new local outbreaks in Moscow and Irkutsk. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobkov, A. F., E. V. Kazennova, L. M. Selimova, T. A. Khanina, N. N. Ladnaya, M. R. Bobkova, A. V. Kravchenko, G. S. Ryabov, A. L. Sukhanova, E. V. Buravtsova, V. V. Pokrovsky, and J. N. Weber. 2003. Molecular-virological features of the HIV-1 epidemic in Russia and other the CIS countries. Vestn. Akad. Med. Nauk. SSSR:83-85. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borman, A. M., S. Paulous, and F. Clavel. 1996. Resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to protease inhibitors: selection of resistance mutations in the presence and absence of the drug. J. Gen. Virol. 77:419-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner, B. G., and M. A. Wainberg. 2003. The role of antiretrovirals and drug resistance in vertical transmission of HIV-1 infection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 918:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrillo, A., K. D. Stewart, H. L. Sham, D. W. Norbeck, W. E. Kohlbrenner, J. M. Leonard, D. J. Kempf, and A. Molla. 1998. In vitro selection and characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with increased resistance to ABT-378, a novel protease inhibitor. J. Virol. 72:7532-7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delwart, E. L., E. G. Shpaer, J. Louwagie, F. McCutchan, M. Grez, H. Ruebsamen-Waigmann, and J. I. Mullins. 1993. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay. Science 262:1257-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drobyshev, A., N. Mologina, V. Shik, D. Pobedimskaya, G. Yershov, and A. Mirzabekov. 1997. Sequence analysis by hybridization with oligonucleotide microchip: identification of beta-thalassemia mutations. Gene 188:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duwe, S., M. Brunn, D. Altmann, O. Hamouda, B. Schmidt, H. Walter, G. Pauli, and C. Kucherer. 2001. Frequency of genotypic and phenotypic drug-resistant HIV-1 among therapy-naive patients of the German seroconverter study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 26:266-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egger, M., B. Hirschel, P. Francioli, P. Sudre, M. Wirz, M. Flepp, M. Rickenbach, R. Malinverni, P. Vernazza, and M. Battegay. 1997. Impact of new antiretroviral combination therapies in HIV-infected patients in Switzerland: prospective multicentre study. BMJ 315:194-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP: phylogenetic interference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5:164-166. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonjungo, P. N., E. N. Mpoudi, J. N. Torimiro, G. A. Alemnji, L. T. Eno, E. J. Lyonga, J. N. Nkengasong, R. B. Lal, M. Rayfield, M. L. Kalish, T. M. Folks, and D. Pieniazek. 2002. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 group M protease in Cameroon: genetic diversity and protease inhibitor mutational features. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:837-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heyndrickx, L., W. Janssens, L. Zekeng, R. Musonda, S. Anagonou, G. Van der Auwera, S. Coppens, K. Vereecken, K. De Witte, R. Van Rampelbergh, M. Kahindo, L. Morison, F. E. McCutchan, J. K. Carr, J. Albert, M. Essex, J. Goudsmit, B. Asjo, M. Salminen, A. Buve, and G. van Der Groen. 2000. Simplified strategy for detection of recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 group M isolates by gag/env heteroduplex mobility assay. J. Virol. 74:363-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holguin, A., A. Alvarez, and V. Soriano. 2002. High prevalence of HIV-1 subtype G and natural polymorphisms at the protease gene among HIV-uninfected immigrants in Madrid. AIDS 16:1163-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kantor, R., and D. Katzenstein. 2003. Polymorphism in HIV-1 non-subtype B protease and reverse transcriptase and its potential impact on drug susceptibility and drug resistance evolution. AIDS Rev. 5:25-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz, R. A., and A. M. Skalka. 1994. The retroviral enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63:133-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequence. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konings, F. A. J., P. Zhong, M. Agwara, L. Agyingi, L. Zekeng, J. M. Achkar, L. Ewane, D. R. Saa, E. A. Ze, T. Kinge, and P. N. Nyambi. 2004. Protease mutations in HIV-1 non-B strains infecting drug-naive villagers of Cameroon. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 20:105-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurbanov, F., M. Kondo, Y. Tanaka, M. Zalalieva, G. Giasova, T. Shima, N. Jounai, N. Yuldasheva, R. Ruzibakiev, M. Mizokami, and M. Imai. 2003. Human immunodeficiency virus in Uzbekistan: epidemiological and genetic analyses. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 19:731-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapa, S., M. Mikheev, S. Shchelkunov, V. Mikhailovich, A. Sobolev, V. Blinov, I. Babkin, A. Guskov, E. Sokunova, A. Zasedatelev, L. Sandakhchiev, and A. Mirzabekov. 2002. Species-Level Identification of orthopoxviruses with an oligonucleotide microchip. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:753-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liitsola, K., I. Tashkinova, T. Laukkanen, G. Korovina, T. Smolskaja, O. Momot, N. Mashkilleyson, S. Chaplinskas, H. Brummer-Korvenkontio, J. Vanhatalo, P. Leinikki, and M. O. Salminen. 1998. HIV-1 genetic subtype A/B recombinant strain causing an explosive epidemic in injecting drug users in Kaliningrad. AIDS 12:1907-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liitsola, K, K. Holm, A. Bobkov, V. Pokrovsky, T. Smolskaya, P. Leinikki, S. Osmanov, M. Salminen, et al. 2000. An AB recombinant and its parental HIV type 1 strains in the area of the former Soviet Union: low requirements for sequence identity in recombination. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1047-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukashov, V. V., E. V. Karamov, V. F. Eremin, L. P. Titov, and J. Goudsmit. 1998. Extreme founder effect in an HIV type 1 subtype A epidemic among drug users in Svetlogorsk, Belarus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:1299-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masharsky, A. E., N. A. Klimov, and A. P. Kozlov. 2003. Molecular cloning and analysis of full-length genome of HIV type 1 strains prevalent in countries of the former Soviet Union. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 19:933-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mikhailovich, V., S. Lapa, D. Gryadunov, A. Sobolev, B. Strizhkov, N. Chernyh, O. Skotnikova, O. Irtuganova, A. Moroz, V. Litvinov, M. Vladimirskii, M. Perelman, L. Chernousova, V. Erokhin, A. Zasedatelev, and A. Mirzabekov. 2001. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains resistant to rifampin by hybridization, PCR, and ligase detection reaction on oligonucleotide microchips. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2531-2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirzabekov, A. D., A. Y. Rubina, and S. V. Pankov. 2001. Composition for polymerizing immobilization of biological molecules and method for producing said composition. Patent WO 03/033539 of the Russian Federation. Bull. Izobreteniy (25). (In Russian.)

- 31.Nabatov, A. A., O. N. Kravchenko, M. G. Lyulchuk, A. M. Shcherbinskaya, and V. V. Lukashov. 2002. Simultaneous introduction of HIV type 1 subtype A and B viruses into injecting drug users in Southern Ukraine at the beginning of the epidemic in the former Soviet Union. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 18:891-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novitsky, V. A., M. A. Montano, and M. Essex. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of an HIV-1 subtype A subcluster among injection drug users in the Southern Ukraine. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:1079-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palella, F. J., Jr., K. M. Delaney, A. C. Moorman, M. O. Loveless, J. Fuhrer, G. A. Satten, D. J. Aschman, S. D. Holmberg, et al. 1998. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:853-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pandrea, I., D. Descamps, G. Collin, D. L. Robertson, F. Damond, V. Dimitrienco, S. Gheorghita, M. Pecec, F. Simon, F. Brun-Vezinet, and C. Apetrei. 2001. HIV type 1 genetic diversity and genotypic drug susceptibility in the Republic of Moldova. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1297-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parikh, U., C. Calef, B. Larder, R. Schinazi, and J. W. Mellors. 2002. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance, p. 94-183. In C. L. Kuiken, B. Foley, E. Freed, B. Hahn, B. Korber, P. A. Marx, F. McCutchan, J. W. Mellors, and S. Wolinksy (ed.), HIV sequence compendium 2002. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.Mex.

- 36.Patick, A. K., M. Duran, Y. Cao, D. Shugarts, M. R. Keller, E. Mazabel, M. Knowles, S. Chapman, D. R. Kuritzkes, and M. Markowitz. 1998. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants isolated from patients treated with the protease inhibitor Nelfinavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2637-2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pokrovsky, V. V., T. N. Ermak, V. V. Belyaeva, and O. G. Yurin. 2003. HIV infection: clinics, diagnostics, treatment, p. 418-426. GEOTAR-MED, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian.)

- 38.Resch, W., R. Ziermann, N. Parkin, A. Gamarnik, and R. Swanstrom. 2002. Nelfinavir-resistant, amprenavir-hypersusceptible strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 carrying an N88S mutation in protease have reduced infectivity, reduced replication capacity, and reduced fitness and process the gag polyprotein precursor aberrantly. J. Virol. 76:8659-8666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose, R. E., Y. F. Gong, J. A. Greytok, C. M. Bechtold, B. J. Terry, B. S. Robinson, M. Alam, R. J. Colonno, and P. F. Lin. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral background plays a major role in development of resistance to protease inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1648-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Servais, J., C. Lambert, E. Fontaine, J.-M. Plesseria, I. Robert, V. Arendt, T. Staub, F. Schneider, B. Hemmer, G. Burtonboy, and J.-C. Schmit. 2001. Variant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteases and response to combination therapy including a protease inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:893-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strizhkov, B., A. Drobyshev, V. Mikhailovich, and A. Mirzabekov. 2000. PCR amplification on a microarray of gel-immobilized oligonucleotides: detection of bacterial toxin- and drug-resistant genes and their mutations. BioTechniques 29:844-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugiura, W., K. Shimada, M. Matsuda, T. Chiba, L. Myint, A. Okano, and K. Yamada. 2003. Novel enzyme-linked minisequence assay for genotypic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4971-4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vahey, M., M. E. Nau, S. Barrick, J. D. Cooley, R. Sawer, A. A. Sleeker, P. Vickerman, S. Bloor, B. Larder, N. L. Michael, and S. A. Wegner. 1999. Performance of the Affimetrix GeneChip HIV PRT 440 platform for antiretroviral drug resistance genotyping of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clades and viral isolates with length polymorphisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2533-2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walsh, J. C., A. L. Pozniak, M. R. Nelson, S. Mandalia, and B. G. Gazzard. 2002. Virologic rebound on HAART in the context of low treatment adherence with a low prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 30:278-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weber, J., H. R. Rangel, B. Chakraborty, M. L. Marotta, H. Valdez, K. Fransen, E. Florence, E. Connick, K. Y. Smith, R. L. Colebunders, A. Landay, D. R. Kuritzkes, M. M. Lederman, G. Vanham, and M. E. Quinones-Mateu. 2003. Role of baseline pol genotype in HIV-1 fitness evolution. J. Aquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 33:448-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson, J. W., P. Bean, T. Robins, F. Graziano, and D. H. Persing. 2000. Comparative evaluation of three human immunodeficiency virus genotyping systems: the HIV-GenotypR method, the HIV PRT GeneChip assay, and the HIV HIV-1 RT line probe assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3022-3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong, P., L. Kang, Q. Pan, F. Konings, S. Burda, L. Ma, Y. Xue, X. Zheng, Z. Jin, and P. Nyambi. 2003. Identification and distribution of HIV type 1 genetic diversity and protease inhibitor resistance-associated mutations in Shanghai, P. R. China. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 34:91-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhusupov, B. S. 2002. Review of the HIV/AIDS situation in the Republic of Kazakhstan. www.hivrussia.org.