Abstract

Members of our laboratory previously generated and described a set of avian reovirus (ARV) temperature-sensitive (ts) mutants and assigned 11 of them to 7 of the 10 expected recombination groups, named A through G (M. Patrick, R. Duncan, and K. M. Coombs, Virology 284:113-122, 2001). This report presents a more detailed analysis of two of these mutants (tsA12 and tsA146), which were previously assigned to recombination group A. The capacities of tsA12 and tsA146 to replicate at a variety of temperatures were determined. Morphological analyses indicated that cells infected with tsA12 at a nonpermissive temperature produced ∼100-fold fewer particles than cells infected at a permissive temperature and accumulated core particles. Cells infected with tsA146 at a nonpermissive temperature also produced ∼100-fold fewer particles, a larger proportion of which were intact virions. We crossed tsA12 with ARV strain 176 to generate reassortant clones and used them to map the temperature-sensitive lesion in tsA12 to the S2 gene. S2 encodes the major core protein σA. Sequence analysis of the tsA12 S2 gene showed a single alteration, a cytosine-to-uracil transition, at nucleotide position 488. This alteration leads to a predicted amino acid change from proline to leucine at amino acid position 158 in the σA protein. An analysis of the core crystal structure of the closely related mammalian reovirus suggested that the Leu158 substitution in ARV σA lies directly under the outer face of the σA protein. This may cause a perturbation in σA such that outer capsid proteins are incapable of condensing onto nascent cores. Thus, the ARV tsA12 mutant represents a novel assembly-defective orthoreovirus clone that may prove useful for delineating virus assembly.

Avian reoviruses (ARVs) are members of the Orthoreovirus genus of the family Reoviridae. ARVs generally are considered to be similar to their mammalian counterparts in structure and molecular composition (40, 43). Both ARVs and mammalian reoviruses (MRVs) have a genome consisting of 10 segments of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) enclosed by a double-shelled capsid made from eight different proteins. The ARV outer capsid contains three proteins (the major proteins μB and σB and the minor protein σC), and the inner core structure is composed of five proteins (the major core proteins λA and σA, the core spike protein λC, and the minor core proteins λB and μA) (25, 26). ARVs are important pathogens of poultry that may cause considerable economic losses in poultry farming (reviewed in references 22, 37, and 44). Although their pathological effects have been extensively investigated, the basic biology, structure, function, and assembly of ARVs remain poorly understood.

The segmented natures of reovirus genomes, the monocistronic nature of virtually all of the gene segments, and strain-dependent mobility differences of the genes in polyacrylamide gels have provided intertypic reassortants for use, and these genetic tools have been extensively used to assign biologic functions to most MRV genes and their protein products (for examples, see references 3, 19, 24, 35, 41, 45, and 48). In addition, conditionally lethal mutants, particularly those that are temperature sensitive, have served as powerful tools to delineate many biologic processes in virology (for examples, see references 4, 6, 7, 29, and 30). The use of MRV ts mutants has elucidated many aspects of MRV replication (3, 8, 10, 16, 20, 23, 27, 28, 38, 42, 49). We have used assembly-defective MRV ts mutants to determine how the multiprotein-multi-RNA reoviruses are assembled (reviewed in reference 8). A precise determination of the molecular mechanisms involved in viral assembly may help us to combat disease propagation by targeting susceptible steps along the assembly pathway (34).

In contrast to the case for the well-studied MRVs, our knowledge of ARV structure and assembly is less complete. We have initiated such studies with ARV strains ARV138 and ARV176. ARV138 can be distinguished from ARV176 in polyacrylamide gels because every ARV138 gene segment migrates at a different rate from that of its cognate ARV176 gene. Recently, members of our laboratory chemically generated a set of 17 ARV ts mutants by the mutagenesis of ARV138. We assigned 11 of these mutants to 7 of the 10 expected recombination groups, named A through G, and began to characterize them (33). Recombination group A contains two mutant clones (tsA12 and tsA146). Phenotypic differences between ARVs and MRVs have been reported, including both ARVs' lack of hemagglutination activity and their capacity to induce cell fusion (15, 32, 37). These differences suggest that some aspects of the ARV and MRV viral life cycle differ, and they illustrate the need for comparative analyses. The availability of novel ARV ts mutants allows us to continue to use this valuable genetic tool to extend our knowledge toward a better understanding of the basic biology, structure, function, and assembly of ARVs. For this study, we undertook a more thorough characterization of the ARV mutants in the A group, namely tsA12 and tsA146. The defect in tsA12 resulted in the accumulation of core-like particles at nonpermissive temperatures. Reassortant mapping of tsA12 showed that it contains a ts lesion in the S2 gene segment which encodes the major core protein σA. The sequences of the mutated genes were determined, and the locations of the altered amino acids were identified within the comparable MRV core crystal structure. These characterization and morphological analyses of tsA12 have led to a more direct comparison between ARV and MRV protein structure and function and provide a more complete picture of the assembly of these complex particles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

ARV138, ARV176, and group A ts mutant clones tsA12 and tsA146 derived from ARV138 are laboratory stocks. Quail QM5 fibrosarcoma cells were maintained in medium 199 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 10% tryptose phosphate broth, and 2 mM glutamine. Viral infections were carried out on QM5 cell monolayers and incubated in the above medium supplemented with 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin sulfate/ml, and 1 μg of amphotericin B/ml, as described previously, and viral titers were determined by a plaque assay (33).

Virus growth curves.

The replicative capacities of the three ARV clones at various temperatures were determined by infecting QM5 cells with each clone at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 PFU/cell for 1 h. After adsorption, the inoculum was removed, and the monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and overlaid with medium 199. At various times postinfection, cells were harvested and disrupted by freeze-thawing twice and sonication. The yield of infectious progeny virions was determined by a plaque assay on QM5 cells as described previously (33).

Thin-section electron microscopy of ARV-infected cells.

Subconfluent QM5 monolayers in P100 culture dishes were infected with ARV138, tsA12, or tsA146 at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell and were incubated for either 22 h at 39.5°C or 30 h at 33.5°C (approximately one round of replication). The cells were harvested by trypsin digestion, fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde, and processed as described previously (19). Briefly, the fixed cells were pelleted, washed three times with SC-Mg buffer (100 mM sodium cacodylate, 10 mM magnesium chloride, pH 7.4), and fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. The cell pellets were mixed with an equal volume of molten 3% low-melting-point agarose and allowed to cool to create cell-agarose blocks. Cell-agarose blocks were stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate, dehydrated with acetone, infiltrated with DER 332-732 plastic embedding medium, and polymerized. Thin sections were cut by using a diamond knife (Microstar, Huntsville, Tex.) with an LKB Ultratome III ultramicrotome (LKB, Uppsala, Sweden), stained with saturated ethanolic uranyl acetate and 0.25% lead citrate, and viewed in a Philips 201 electron microscope operated at an acceleration voltage of 60 keV.

Morphological quantitation of subviral particle types produced in ARV-infected cells.

Subconfluent QM5 monolayers were infected with ARV138, tsA12, or tsA146 at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell. Infections were incubated for either 22 h at 39.5°C or 30 h at 33.5°C. The quantities of various subviral particle types produced were determined as described previously (18, 20). Briefly, the infections were freeze-thawed, the cell debris was cleared by brief centrifugation, and aliquots of supernatant were pelleted through potassium tartrate cushions. The pellets were resuspended in 0.1% glutaraldehyde in medium 199, fixed on ice, centrifuged directly onto electron microscope grids, stained with 2.5 mM phosphotungstic acid, and examined by electron microscopy. All viral particles in five nonadjacent grid squares from the four outer quadrants and the central area of the grid were counted, and differences in particle distributions were evaluated by chi-square analysis.

Generation and identification of reassortants.

Reassortants were generated essentially as described previously (33). Briefly, subconfluent QM5 monolayers were coinfected with the mutant clone tsA12 and wild-type ARV176 at various MOI ratios (5/5, 2/8, and 8/2 PFU per cell). Infections were incubated at 33.5°C for 32 h to generate reassortants, freeze-thawed twice, and sonicated, and serial dilutions were plated and incubated at 33.5°C. Individual plaques separated by ≥0.75 cm were picked and amplified, and the RNAs were resolved in sodium dodecyl sulfate-12.5% polyacrylamide slab gels. Reassortant clones were identified by comparison to tsA12 and ARV176 RNA patterns.

EOP assays.

The ARV efficiency of plating (EOP) assay was described previously (33). Briefly, QM5 cell monolayers in six-well tissue culture plates were infected with serial 10-fold dilutions of each viral stock in duplicate and then incubated at 33.5°C (permissive temperature) and 39.5°C (nonpermissive temperature). EOP values were determined by dividing the titer at 39.5°C by that at 33.5°C for each clone. Non-ts clones were expected to have EOP values within an order of magnitude of 1. In contrast, ts clones were expected to have EOP values that were significantly lower than 0.1 (8).

Sequencing of the S2 gene.

QM5 cells were infected with ARV138, tsA12, or tsA146 at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell and incubated at 33.5°C for 4 to 6 days. The cells were freeze-thawed, cell debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation, and viruses were pelleted through 30% sucrose cushions (25,000 rpm, 12 h, 5°C, Beckman SW28 rotor). Genomic dsRNAs were extracted with phenol-chloroform (39). Terminal oligonucleotide primers complementary to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the ARV138 S2 genome segment (GenBank accession no. AF059717), and additional ones as needed for internal sequencing, were designed for reverse transcription-PCR and sequencing. The primers were purchased from Gibco-BRL. cDNA copies of the S2 genes of each virus were produced by using the terminal primers and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL). The cDNAs were amplified by use of the Expand Long Template PCR system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Boehringer Manheim) and were resolved in 0.9% agarose gels. The cDNA bands corresponding to the 1.3-kb gene were excised and extracted by use of a Qiaquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequences of the eluted cDNAs were determined in both directions by use of an ABI Prism Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and were analyzed with DNASTAR software (Madison, Wis.).

Placement of σA mutations within reovirus core crystal structure.

The positions of avian reovirus σA mutations relative to those of MRV σ2 were identified by amino acid sequence alignments by the use of MegAlign in the DNASTAR package. The mammalian reovirus core crystal structure (PDB 1EJ6) (36) was manipulated with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org) to identify probable locations of ARV σA and MRV σ2 mutations.

RESULTS

Replication of tsA12 is impaired at temperatures of 37°C and higher.

Previous EOP assays indicated that tsA12 forms plaques poorly at ≥37°C and that tsA146 forms plaques poorly at temperatures of >38°C (33). However, the rate and extent of impaired replication (as measured by the production of infectious progeny) of these two viruses at elevated temperatures have not been characterized. We performed a direct comparison of the mutations' deleterious effects by examining the production of infectious progeny at various temperatures between 33.5 and 39.5°C.

There was little difference between the infectious progeny virus production of tsA12 and that of its parental wild-type (WT) ARV138 at 33.5°C (Fig. 1a). The final yields from cultures infected with tsA146 were consistently two- to sevenfold higher than those of corresponding cultures infected with WT ARV138 and tsA12 at 33.5°C (Fig. 1a). In contrast to the titers of WT ARV138 (which were only marginally changed at a restrictive temperature of 39.5°C), the titers of tsA12 and tsA146 were 10- to 70-fold lower at later times postinfection (p.i.) (Fig. 1b). Clonal differences in infectious viral production were also seen as the incubation temperature increased. For example, at 30 h p.i., WT ARV138 virus production exhibited minor changes at all tested temperatures between 33.5 and 39.5°C (Fig. 1c). tsA12 progeny production was markedly reduced (∼100-fold) compared to WT ARV138 progeny production at 37°C and remained ∼100-fold lower at all higher temperatures (Fig. 1c). In contrast, tsA146 progeny production was progressively reduced from 5-fold to about 75-fold as the restrictive temperature was progressively elevated (Fig. 1c). Similar patterns were observed at most other time points examined.

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of viral growth in QM5 cells at various temperatures. QM5 cell monolayers were infected with wild-type (WT) ARV138, tsA12, or tsA146 at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell and incubated at 33.5°C (a) and 39.5°C (b). At various times postinfection, cell monolayers were harvested, and yields of infectious progeny virus were determined by a plaque assay. The results are the averages of twoseparate experiments, and error bars represent 1 standard deviation. (c) Data were compiled from separate growth curves conducted at various temperatures, and those data corresponding to 30 h p.i. were extracted for strain comparisons.

tsA12 and tsA146 assemble fewer particles in restrictive infections.

The first step in the characterization of a conditionally lethal mutant is a determination of the mutation's effect upon virus morphology and viral inclusions under both permissive and restrictive conditions. Electron microscopy has been used in this way for many of the MRV ts mutants (9, 11, 17, 19). We initiated similar studies with our ARV ts mutants. QM5 cells were infected with parental WT ARV138 or the tsA12 or tsA146 mutant at both permissive (33.5°C) and restrictive (39.5°C) temperatures, fixed, sectioned, and examined. There were no significant ultrastructural changes associated with apoptotic or necrotic cell death in any of the WT and ts mutant infections at the permissive or restrictive temperature (Fig. 2). Multinucleate giant cells that contained viral inclusions were observed in all permissive WT and ts mutant infections. Large perinuclear inclusions were observed in 91% of single cells in permissive WT infections. The inclusions were more distinctly paracrystalline than those seen in MRV infections (19) and consisted mainly of complete virions and the “top component” (empty virus particles consisting of all structural proteins and no genome) (Fig. 2A). Viral inclusions were observed in 76% of single cells in restrictive WT infections. These inclusions were larger and more paracrystalline than those in permissive infections (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Thin-section electron micrographs of permissive (33.5°C) and restrictive (39.5°C) cultures of WT ARV138 (A and B), tsA12 (C and D), and tsA146 (E to H). QM5 cells were infected at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell and then incubated at 33.5°C for 30 h (A, C, E, G, and H) or 39.5°C for 22 h (B, D, and F). Bar = 1.0 μm for panels A-G and 0.2 μm for the insets and panel H. (F, inset) Top component is designated by an arrowhead; the core is designated by arrows. Disruption was observed in the annulate lamallae in both permissive (G and H) and restrictive cultures of tsA146.

Viral inclusions in ts mutant infections differed significantly from those in WT-infected cells. Inclusions were observed in 78% of tsA12-infected cells under permissive conditions. The inclusions did not form paracrystalline arrays, were smaller than those seen in WT infections, and were comprised of nearly equal proportions of complete and top-component virions (Fig. 2C). Cells infected with the tsA12 mutant and cultured at the restrictive temperature contained very small, highly disorganized inclusions in only 8% of all cells examined, and the inclusions were comprised mainly of top-component particles (Fig. 2D). The permissive tsA146 inclusions differed ultrastructurally from those seen with WT ARV138 and tsA12 permissive infections. Despite our ensuring that the MOI was ≥10 PFU/cell, tsA146 inclusions were observed in only 26% of infected cells and were generally small, with a central dense body of unassembled viral proteins surrounded by a disorganized aggregate of assembled top components, outer shells, and complete virus particles (Fig. 2E). Restrictive tsA146 inclusions were observed in only 11% of infected cells, were very small, and were comprised mainly of unassembled viral proteins. The periphery of the inclusions contained what appeared to be viral RNAs coalescing into core-like particles, and some assembled top-component particles were observed in the center of the inclusions (Fig. 2F, inset). The annulate lamellae were very disorganized in both permissive (Fig. 2G and H) and restrictive tsA146 infections.

tsA12 produces core-like particles at the nonpermissive temperature.

In addition to direct morphological analyses of thin-sectioned infected cells, direct particle counting of negatively stained cell lysates serves as an ideal way to determine the existence and quantity of different structures (20, 27). Therefore, we also performed direct particle counting of all types of particles released from lysed cells for each mutant at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures. Table 1 shows the proportions of structures produced by ARV138, tsA12, and tsA146 at both permissive and restrictive temperatures. The predominant structural forms produced by ARV138 were complete virions and top components at both permissive and restrictive temperatures (Table 1). The proportions of all particles produced by ARV138 were similar at both temperatures. Cells infected with tsA12 and grown at nonpermissive temperatures produced approximately 80-fold fewer viral particles than cells infected with ARV138. Cells infected with tsA146 produced 13-fold fewer viral particles at 39.5°C than cells infected with ARV138 at 39.5°C. The distribution of particles produced by the mutants was different from the distribution of ARV138 particles. At 33.5°C, the most common type of particle produced by tsA12 was virions (70%), and top components comprised 19% of the particles produced. There was a significant increase in the proportion of core-like particles produced by tsA12 at the restrictive temperature (from 5 to 31%; P < 0.0001) and a trend toward increased proportions of top components and outer shells. The proportions of types of particles produced by tsA146 at the permissive temperature were similar to those seen with ARV138, but there was a significant increase in the proportion of complete virions and a significant decrease in the proportion of top-component structures (P < 0.0001 for both) at the restrictive temperature compared to cells infected with ARV138 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of types of particles produced by ARV138, tsA12, and tsA146 at permissive and nonpermissive temperaturesa

| Clone | Temp (°C) | Total no. of particlesb | Total no. of particles/mlc | Proportion of particle type (% [SEM])d

|

No. of particlese/PFU at:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virion | Top component | Core | Outer shell | 33.5°C | 39.5°C | ||||

| ARV138 | 33.5 | 5,273 | 2.2 × 109 | 40.4 (7.7) | 53.0 (6.0) | 3.7 (1.8) | 2.9 (0.4) | 1,038 | 1,482 |

| 39.5 | 28,127 | 7.2 × 108 | 43.7 (15.7) | 50.7 (15.5) | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.2) | 238 | 304 | |

| tsA12 | 33.5 | 1,524 | 8.9 × 108 | 69.8 (21.2) | 18.7 (19.1) | 5.0 (2.6) | 6.5 (1.1) | 698 | 4.1 × 106 |

| 39.5 | 783 | 9.6 × 106 | 24.8 (7.5) | 35.0 (8.9) | 31.1 (18.6) | 9.1 (2.5) | 26 | 1.6 × 104 | |

| tsA146 | 33.5 | 6,923 | 4.2 × 109 | 37.8 (9.1) | 50.8 (8.6) | 6.4 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.9) | 1,049 | 1.6 × 107 |

| 39.5 | 3,185 | 5.6 × 107 | 62.8 (14.9) | 33.1 (11.38) | 2.1 (4.6) | 2.0 (1.0) | 398 | >3.5 × 105 | |

Calculated from three separate experiments.

Total number of viral and subviral particles counted.

Number of identifiable viral particles in cell lysates, calculated as described previously (18).

Proportion of indicated particle type, expressed as a percentage of the total number of particles produced, with the standard error of the mean shown in parentheses.

Determined for virion particles, calculated as follows: [(total no. of particles/ml × percentage of particles that are virions) ÷ titer at the indicated temperature].

The formation of proportionately more complete virions by the tsA146 mutant at a restrictive temperature was consistent with the results for this mutant by thin-section electron microscopy, by which nucleic acids were seen as dense condensates at the periphery of the inclusions for restrictive-temperature cultures. Together, these two observations suggest that the mutation in tsA146 may also affect the ability of the σA protein to interact with dsRNA at elevated temperatures, promoting the assembly of complete virions rather than top-component virions.

The ts lesion in tsA12 resides in the S2 gene.

We performed reassortant mapping to identify the gene responsible for the tsA12 phenotype. tsA12 was crossed with ARV176, and a total of 244 clones from the mixed infection were picked, amplified, and electropherotyped. Of these, 18 were identified as unique reassortants. Three additional clones (186, 220, and 222) exhibited aberrant mobilities of their S2 gene segments in a polyacrylamide gel. The parental origins of their S2 gene segments were identified by their restriction fragment length polymorphisms (data not shown). The reassortants were divided into two panels by EOP analyses, those that retained the ts phenotype and those that had a non-ts phenotype (Table 2). Every reassortant that behaved like the tsA12 mutant had its S2 gene segment derived from tsA12. Every reassortant that behaved like WT ARV176 contained an S2 gene segment derived from ARV176. The other nine gene segments were randomly distributed with respect to phenotype. These data indicate that the tsA12 mutation resides in the S2 gene, which encodes the major core protein σA. Interestingly, every reassortant that contained the aberrantly migrating S2 gene also contained L2 and S4 genes derived from tsA12 and an S3 gene derived from WT ARV176.

TABLE 2.

Electropherotypes and EOP values of ARV176 × tsA12 reassortants

| Clone | Electropherotype of geneb

|

EOPa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | L3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | ||

| 125 | A | A | 7 | A | A | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | 0.0000064 |

| tsA12 | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 0.000045 |

| 131 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | A | A | A | A | A | 0.000068 |

| 187 | A | A | A | 7 | A | A | A | A | A | A | 0.000094 |

| 160 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | A | 7 | 0.000096 |

| 192 | A | A | 7 | 7 | A | A | A | A | A | A | 0.00025 |

| 26 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | A | A | 7 | 0.00034 |

| 186 | A | A | A | 7 | A | A | 7 | Ac | 7 | A | 0.00069 |

| 151 | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | A | A | 7 | 0.00081 |

| 64 | A | 7 | 7 | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 0.0011 |

| 220 | 7 | A | A | A | A | 7 | 7 | Ac | 7 | A | 0.0025 |

| 222 | A | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | A | Ac | 7 | A | 0.0040 |

| 12 | A | A | 7 | A | 7 | A | 7 | A | A | A | 0.0043 |

| 169 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 0.19 |

| 65 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0.27 |

| 229 | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | A | 0.41 |

| 30 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 0.53 |

| 148 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | A | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0.55 |

| 215 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0.69 |

| 243 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0.74 |

| ARV176 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0.76 |

| 194 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 1.42 |

| 159 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | A | 7 | 7 | 7 | 20.52 |

| Exceptions | 5 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 7 | |

EOP, efficiency of plating [(titer at 39.5°C) + (titer at 33.5°C)]. Values represent the averages obtained from two or three experiments.

A, tsA12; 7, ARV176.

Gene segment exhibits an aberrant mobility in 12.5% polyacrylamide gels, and the parental origin was identified by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis.

The tsA12 S2 gene contains one alteration.

The S2 gene segments from tsA12, tsA146, and our parental laboratory strain of ARV138 were sequenced and compared to the ARV138 S2 sequence reported in GenBank (accession number AF059717). The S2 gene of the ARV138 laboratory strain that was used to generate our ARV ts mutants had no nucleotide changes in the σA open reading frame, whereas the tsA12 S2 gene contained one nucleotide alteration. This change was a C-to-U transition at nucleotide position 488, which leads to a proline-to-leucine substitution at amino acid position 158 in the σA protein (Fig. 3A). Although the three-dimensional structure of ARV is currently not known, the region that corresponds to Pro160 in the known MRV σ2 protein is located in the middle of the σ core protein (Fig. 3C to E), where it may affect interactions with the outer capsid μ protein, thereby preventing the outer capsid from condensing onto cores and giving rise to a significantly larger proportion of core particles under restrictive conditions. In contrast, the MRV σ2 mutant tsC447 lesion (in which Asn383 is changed to Asp) lies at the end of a long α helix on the outer surface of σ2 (Fig. 3C to E), where it may affect σ2-σ2 interactions, resulting in the failure of core formation. The tsA146 S2 gene contained two transitions, from C to T, at nucleotide positions 178 and 884, each of which resulted in amino acid substitutions in the σA protein (Fig. 3). These alterations (Pro55-Ser and Thr290-Ile) are predicted to reside in different σA regions.

FIG. 3.

Alterations in predicted amino acid sequences of MRV and ARV S2 gene products and locations of the mutations in the asymmetric unit of the MRV core crystal structure. Amino acid positions are numbered above the sequences. (A) Locations of various amino acid residues in the primary structures of MRV σ2 (top), ARV σA (middle), and NBV σ1 (bottom) proteins. Amino acid alterations responsible for the ts phenotype are indicated in red. (B) Crystal structure of MRV core protein (36). (C) Close-up of crystal asymmetric unit (outlined in panel B),adapted and manipulated with PyMOL and shown in ribbon format. (D and E) Close-up of one of the σ2 subunits from panel C showing locations of MRV σ2 core protein mutations at amino acid position 383 (yellow spheres), MRV σ2 amino acid position 160 (gray spheres; presumed to correspond to ARV tsA12 σA Pro158-Leu mutation at amino acid position 158), MRV σ2 amino acid position 56 (cyan spheres; presumed to correspond to ARV tsA146 Pro55-Ser mutation), and MRV σ2 amino acid position 292 (pink spheres; presumed to correspond to ARV tsA146 Thr292-Ile mutation). The view in panel E is rotated 30° to the left compared to that in panel D, and the indicated mutations in panels C to E (yellow, cyan, gray, and pink spheres) correspond to the mutated residues in a space-filling format on the ribbon backbone within the σ2 crystal structure (green).

DISCUSSION

Analyses of conditionally lethal MRV ts mutants have proven useful for delineating the MRV structure, function, and assembly (3, 8, 20, 21, 23, 27, 28, 38, 42, 49). In contrast to their mammalian counterparts, ARV ts mutants for use in dissecting ARV structure and assembly have not been reported previously. We have generated a panel of chemically derived ARV ts mutants that provide us with the capacity to perform similar studies.

For this report, we characterized two mutants (tsA12 and tsA146) of recombination group A. We found that the mutations in tsA12 and tsA146 caused different phenotypic responses. This was evident by examining the replication of the two mutants at various temperatures. The production of infectious tsA12 progeny was markedly reduced at 37°C or higher (Fig. 1C). The production of infectious tsA146 progeny was also reduced at temperatures above 37°C, but tsA146 replication was impaired to a larger extents as the restrictive temperature was increased (Fig. 1C). This indicates that the mutation in tsA12 differs from the mutation in tsA146 (as confirmed by sequence analysis) and that the tsA12 mutation induces the ts phenotype at a lower restrictive temperature. In addition to the ts phenotypic difference seen in replication, direct particle counting of tsA12- and tsA146-infected cell lysates revealed that tsA12, but not tsA146, accumulated significant amounts of core-like particles at the nonpermissive temperature (Table 1). Thus, tsA12 represents a novel assembly-defective mutant which is not able to assemble past the core. An examination of tsA12 by thin-section electron microscopy yielded results consistent with direct particle counting except that the core structures were not identified by thin-section electron microscopy. The inability to identify large numbers of core structures in the thin-sectioned tsA12 restrictive infection may have been caused by viral structural and nonstructural proteins transiently associating to form replicase particles (31) and, ultimately, nascent cores (5), which may have disguised the appearance of nascent particles.

The lesion in tsA12 that results in the ts phenotype was mapped to the S2 gene by reassortant mapping (Table 2). The ARV S2 gene segment is 1,324 bp long (13) and encodes the major core protein σA, a 45.5-kDa protein (47) consisting of 416 amino acids (13). This protein has been proposed to have a similar structure and function with its counterpart MRV major core protein σ2 (14, 47), which is also encoded by the S2 gene. Thus, it is likely that both ARV σA and MRV σ2 (36) bind to the outer face of the core structure and act as a clamp to hold the core structure together. Although the protein sequences of ARV σA and MRV σ2 have approximately 30% similarity (13), σA and σ2 share similar predicted secondary structures (47). Moreover, it has been reported that both σA and σ2 have dsRNA-binding activities (12, 47), indicating an important role of this major core protein in reovirus transcription and replication. However, the mechanism by which the major σ core protein is involved in these phenotypes is not understood and needs to be further investigated.

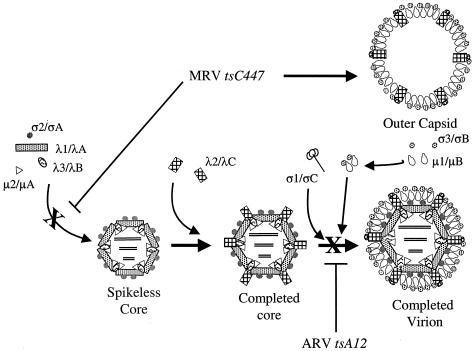

Interestingly, while ARV tsA12 assembled core structures in restrictive infections (Table 1), the cognate MRV mutant tsC447 fails to accumulate cores but synthesizes empty outer capsid structures at the nonpermissive temperature (9, 17, 27). An analysis of the deduced protein sequence of the tsA12 S2 gene revealed that there is a single amino acid substitution (proline to leucine) at position 158 (Fig. 3A). Although the detailed ARV core structure is not currently known, the use of the available MRV core crystal asymmetric unit (PDB 1EJ6) (36) as a model predicted that the altered amino acid lies under the outer face of the σA protein (Fig. 3C to E). This mutation might affect the distal side of the protein, where it prevents condensation of outer capsid proteins onto the core, and thus may lead to the alterations in particle distribution seen for tsA12 at the nonpermissive temperature.

The sequence of the comparable MRV tsC447 mutant gene has been determined to contain several nucleotide alterations that lead to amino acid substitutions (46). However, extensive genetic reversion analyses indicated that an asparagine-to-aspartic acid change at amino acid position 383 is most likely responsible for the failure of tsC447 to assemble core particles at the nonpermissive temperature (9). The region of σ2 near or at Asp383 is positioned on the outer surface of the protein (Fig. 3C to E). The introduction of a mutated residue in this region of σ2 might affect σ2-σ2 interactions that would normally lead to core capsid assembly. An alignment of the major σ core protein sequences of MRV, ARV, and Nelson Bay reoviruses (NBV) (14) revealed that all of them contain proline residues at amino acid position 158 (in ARV and NBV) or 160 (MRV) and asparagine residues at amino acid position 382 (ARV and NBV) or 383 (MRV), implying the structural importance of these residues (Fig. 3A). In addition, the ARV and MRV sequences share a conserved threonine residue (at position 290 in ARV and position 292 in MRV) and the ARV and NBV sequences share a conserved proline residue at position 55; the MRV sequences have an alanine in position 56 (Fig. 3A). Thus, the high degree of sequence conservation across these residues among the different species suggests that there are similar structural motifs among the major σ core proteins, which also suggests that a mutation caused at one of these residues might result in structural instability. Indeed, an examination of a variety of DNASTAR secondary structure prediction algorithms suggested that every amino acid alteration in each ARV and MRV ts mutant leads to changes in secondary structure, hydrophobicity, and antigenicity (data not shown). Therefore, the different mutations in the cognate major core proteins of MRV and ARV could lead to different phenotypic responses during particle assembly (Fig. 4). Continued comparative analyses of ARV ts mutants and their MRV counterparts will not only allow us to expand our understanding of viral proteins, but should also help us to delineate virion assembly.

FIG. 4.

Proposed reovirus assembly pathways. The locations and identities of the eight major structural proteins of the virus are indicated. Blocks in the pathways mediated by ARV tsA12 or MRV tsC447 are marked with an “X.”

Finally, the observation of core condensates at the periphery of viral inclusions in the tsA146 restrictive-temperature cultures and the shift in the proportion of particles produced from top components to complete virions suggests an alteration in the ability of the σA core protein to interact with dsRNA, probably mediated by one or both of the identified tsA146 σA mutations. We are continuing our investigations into the interactions of σA as defined by the mutant tsA146, which may help to explain the mechanisms of ssRNA sequestration in the viral inclusion by μNS, the addition of λC and σA to the early replicase particle (1, 2), and the synthesis of dsRNA in the formation of the complete replicase particle (31, 50).

Acknowledgments

We thank Jieyuan Jiang, Ita Hadzisejdic, Lindsay Noad, and Anh Tran for critical reviews of this study and Archibald Nartey for maintenance of cultured cells.

This research was supported by grants MT-11630 and GSP-48371 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to K.M.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Acs, G., H. Klett, M. Schonberg, J. Christman, D. H. Levin, and S. C. Silverstein. 1971. Mechanism of reovirus double-stranded ribonucleic acid synthesis in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 8:684-689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antczak, J. B., and W. K. Joklik. 1992. Reovirus genome segment assortment into progeny genomes studied by the use of monoclonal antibodies directed against reovirus proteins. Virology 187:760-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker, M. M., M. I. Goral, P. R. Hazelton, G. S. Baer, S. E. Rodgers, E. G. Brown, K. M. Coombs, and T. S. Dermody. 2001. Reovirus sigmaNS protein is required for nucleation of viral assembly complexes and formation of viral inclusions. J. Virol. 75:1459-1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black, L. W., M. K. Showe, and A. C. Steven. 1994. Morphogenesis of the T4 head, p. 218-258. In J. D. Karam, J. W. Drake, K. N. Kreuzer, G. Mosig, D. Hall, F. A. Eiserling, L. W. Black, E. Kutter, E. Spicer, K. Carlson, and E. S. Miller (ed.), Molecular biology of bacteriophage T4. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 5.Broering, T. J., J. Kim, C. L. Miller, C. D. Piggott, J. B. Dinoso, M. L. Nibert, and J. S. Parker. 2004. Reovirus nonstructural protein μNS recruits viral core surface proteins and entering core particles to factory-like inclusions. J. Virol. 78:1882-1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carleton, M., and D. T. Brown. 1996. Events in the endoplasmic reticulum abrogate the temperature sensitivity of Sindbis virus mutant ts23. J. Virol. 70:952-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compton, S. R., B. Nelsen, and K. Kirkegaard. 1990. Temperature-sensitive poliovirus mutant fails to cleave VP0 and accumulates provirions. J. Virol. 64:4067-4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coombs, K. M. 1998. Temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 233:69-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coombs, K. M., S. C. Mak, and L. D. Petrycky-Cox. 1994. Studies of the major reovirus core protein sigma 2: reversion of the assembly-defective mutant tsC447 is an intragenic process and involves back mutation of Asp-383 to Asn. J. Virol. 68:177-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross, R. K., and B. N. Fields. 1972. Temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus type 3: studies on the synthesis of viral RNA. Virology 50:799-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danis, C., S. Garzon, and G. Lemay. 1992. Further characterization of the ts453 mutant of mammalian orthoreovirus serotype 3 and nucleotide sequence of the mutated S4 gene. Virology 190:494-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dermody, T. S., L. A. Schiff, M. L. Nibert, K. M. Coombs, and B. N. Fields. 1991. The S2 gene nucleotide sequences of prototype strains of the three reovirus serotypes: characterization of reovirus core protein sigma 2. J. Virol. 65:5721-5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan, R. 1999. Extensive sequence divergence and phylogenetic relationships between the fusogenic and nonfusogenic orthoreoviruses: a species proposal. Virology 260:316-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan, R., Z. Chen, S. Walsh, and S. Wu. 1996. Avian reovirus-induced syncytium formation is independent of infectious progeny virus production and enhances the rate, but is not essential, for virus-induced cytopathology and virus egress. Virology 224:453-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan, R., and K. Sullivan. 1998. Characterization of two avian reoviruses that exhibit strain-specific quantitative differences in their syncytium-inducing and pathogenic capabilities. Virology 250:263-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fields, B. N., R. Laskov, and M. D. Scharff. 1972. Temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus type 3: studies on the synthesis of viral peptides. Virology 50:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields, B. N., C. S. Raine, and S. G. Baum. 1971. Temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus type 3: defects in viral maturation as studied by immunofluorescence and electron microscopy. Virology 43:569-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammond, G. W., P. R. Hazelton, I. Chuang, and B. Klisko. 1981. Improved detection of viruses by electron microscopy after direct ultracentrifuge preparation of specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 14:210-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazelton, P. R., and K. M. Coombs. 1995. The reovirus mutant tsA279 has temperature-sensitive lesions in the M2 and L2 genes: the M2 gene is associated with decreased viral protein production and blockade in transmembrane transport. Virology 207:46-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazelton, P. R., and K. M. Coombs. 1999. The reovirus mutant tsA279 L2 gene is associated with generation of a spikeless core particle: implications for capsid assembly. J. Virol. 73:2298-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito, Y., and W. K. Joklik. 1972. Temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus. I. Patterns of gene expression by mutants of groups C, D, and E. Virology 50:189-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones, R. C. 2000. Avian reovirus infections. Rev. Sci. Technol. 19:614-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keirstead, N. D., and K. M. Coombs. 1998. Absence of superinfection exclusion during asynchronous reovirus infections of mouse, monkey, and human cell lines. Virus Res. 54:225-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucia-Jandris, P., J. W. Hooper, and B. N. Fields. 1993. Reovirus M2 gene is associated with chromium release from mouse L cells. J. Virol. 67:5339-5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez-Costas, J., A. Grande, R. Varela, C. Garcia-Martinez, and J. Benavente. 1997. Protein architecture of avian reovirus S1133 and identification of the cell attachment protein. J. Virol. 71:59-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Costas, J., R. Varela, and J. Benavente. 1995. Endogenous enzymatic activities of the avian reovirus S1133: identification of the viral capping enzyme. Virology 206:1017-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuhisa, T., and W. K. Joklik. 1974. Temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus. V. Studies on the nature of the temperature-sensitive lesion of the group C mutant ts447. Virology 60:380-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mbisa, J. L., M. M. Becker, S. Zou, T. S. Dermody, and E. G. Brown. 2000. Reovirus mu2 protein determines strain-specific differences in the rate of viral inclusion formation in L929 cells. Virology 272:16-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millns, A. K., M. S. Carpenter, and A. M. DeLange. 1994. The vaccinia virus-encoded uracil DNA glycosylase has an essential role in viral DNA replication. Virology 198:504-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitraki, A., and J. King. 1992. Amino acid substitutions influencing intracellular protein folding pathways. FEBS Lett. 307:20-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan, E. M., and H. J. Zweerink. 1975. Characterization of transcriptase and replicase particles isolated from reovirus-infected cells. Virology 68:455-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ni, Y., and R. F. Ramig. 1993. Characterization of avian reovirus-induced cell fusion: the role of viral structural proteins. Virology 194:705-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patrick, M., R. Duncan, and K. M. Coombs. 2001. Generation and genetic characterization of avian reovirus temperature-sensitive mutants. Virology 284:113-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prevelige, P. E., Jr. 1998. Inhibiting virus-capsid assembly by altering the polymerisation pathway. Trends Biotechnol. 16:61-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramig, R. F., T. A. Mustoe, A. H. Sharpe, and B. N. Fields. 1978. A genetic map of reovirus. II. Assignment of the double-stranded RNA-negative mutant groups C, D, and E to genome segments. Virology 85:531-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reinisch, K. M., M. L. Nibert, and S. C. Harrison. 2000. Structure of the reovirus core at 3.6 A resolution. Nature 404:960-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson, M. D., and G. E. Wilcox. 1986. Avian reovirus. Vet. Bull. 56:155-174. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roner, M. R., I. Nepliouev, B. Sherry, and W. K. Joklik. 1997. Construction and characterization of a reovirus double temperature-sensitive mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6826-6830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 40.Schnitzer, T. J., T. Ramos, and V. Gouvea. 1982. Avian reovirus polypeptides: analysis of intracellular virus-specified products, virions, top component, and cores. J. Virol. 43:1006-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherry, B., J. Torres, and M. A. Blum. 1998. Reovirus induction of and sensitivity to beta interferon in cardiac myocyte cultures correlate with induction of myocarditis and are determined by viral core proteins. J. Virol. 72:1314-1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shing, M., and K. M. Coombs. 1996. Assembly of the reovirus outer capsid requires mu 1/sigma 3 interactions which are prevented by misfolded sigma 3 protein in temperature-sensitive mutant tsG453. Virus Res. 46:19-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spandidos, D. A., and A. F. Graham. 1976. Physical and chemical characterization of an avian reovirus. J. Virol. 19:968-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Heide, L. 2000. The history of avian reovirus. Avian Dis. 44:638-641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiner, H. L., M. L. Powers, and B. N. Fields. 1980. Absolute linkage of virulence and central nervous system cell tropism of reoviruses to viral hemagglutinin. J. Infect. Dis. 141:609-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiener, J. R., T. McLaughlin, and W. K. Joklik. 1989. The sequences of the S2 genome segments of reovirus serotype 3 and of the dsRNA-negative mutant ts447. Virology 170:340-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin, H. S., J. H. Shien, and L. H. Lee. 2000. Synthesis in Escherichia coli of avian reovirus core protein σA and its dsRNA-binding activity. Virology 266:33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin, P., M. Cheang, and K. M. Coombs. 1996. The M1 gene is associated with differences in the temperature optimum of the transcriptase activity in reovirus core particles. J. Virol. 70:1223-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou, S., and E. G. Brown. 1996. Stable expression of the reovirus mu2 protein in mouse L cells complements the growth of a reovirus ts mutant with a defect in its M1 gene. Virology 217:42-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zweerink, H. J., E. M. Morgan, and J. S. Skyler. 1976. Reovirus morphogenesis: characterization of subviral particles in infected cells. Virology 73:442-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]