Abstract

Six rhesus macaques were adapted to morphine dependence by injecting three doses of morphine (5 mg/kg of body weight) for a total of 20 weeks. These animals along with six control macaques were infected intravenously with mixture of simian-human immunodeficiency virus KU-1B (SHIVKU-1B), SHIV89.6P, and simian immunodeficiency virus 17E-Fr. Levels of circulating CD4+ T cells and viral loads in the plasma and the cerebrospinal fluid were monitored in these macaques for a period of 12 weeks. Both morphine and control groups showed precipitous loss of CD4+ T cells. However this loss was more prominent in the morphine group at week 2 (P = 0.04). Again both morphine and control groups showed comparable peak plasma viral load at week 2, but the viral set points were higher in the morphine group than that in the control group. Likewise, the extent of virus replication in the cerebral compartment was more pronounced in the morphine group. These results provide a definitive evidence for a positive correlation between morphine and levels of viral replication.

AIDS is a clinical disorder caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, rendering the body highly susceptible to opportunistic infections (11). Current estimates indicate that injection drug users (IDU) constitute approximately one-third of new HIV cases in the United States (8). However, the effect of abused drugs on the natural history of HIV and disease progression among IDU remains ambiguous (1, 9). According to one prospective study, AIDS is the most frequent cause of death among IDU (3), but conflicting reports on the mortality rate among HIV-infected IDU have demonstrated either a survival advantage or a lower survival rate (1, 13). In view of the conflicting evidence in clinical settings, two groups of investigators employed an animal model of HIV and AIDS disease that utilized a closely related virus (simian immunodeficiency virus [SIV]) (4, 16). These studies have also provided conflicting results. In one study, morphine dependence resulted in exacerbation of SIV disease, but sample sizes in this study were too small to draw any meaningful conclusions (16). Furthermore, this study did not show enhanced viral load until 117 weeks after infection. This exacerbation by morphine has been attributed to up-regulation of CCR5 in the human and the monkey T cells (10, 16). In another study the opiate dependence seemed to provide a protective effect after infection with SIVsmm9, but this study lacked a group of concurrent controls, and thus the results from this study also failed to provide a definitive conclusion (4). Furthermore, these studies utilized SIV that does not cause a loss of circulating CD4+ T cells until late-stage infection, whereas infection with HIV type 1 (HIV-1) is always characterized by gradual CD4+-T-cell loss in the blood. Thus, the present study was designed to study the effect of morphine dependence in more closely related settings where rhesus macaques tend to loose CD4+ T cells.

The 12 male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) used for the study ranged in age from 1.5 to 2.5 years and in weight from 3 to 4.2 kg at the time of study initiation. The animals were negative for simian T-cell leukemia virus type 1 and simian retrovirus. These macaques were housed in the Animal Resource Center of the University of Puerto Rico, San Juan. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and the research was performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The macaques were divided into two groups of six animals each, with one group used for establishment of morphine dependence and the other group used as a control. The morphine dependence was established by injecting increasing doses of morphine (1 to 5 mg/kg of body weight over a 2-week period) by the intramuscular route at 8-h intervals. These animals were maintained at three daily doses of morphine (5 mg/kg) for an additional 18 weeks. The control animals were given the same amount of normal saline at the same time. All 12 macaques were infected by the intravenous route with a 2-ml inoculum containing 104 50% tissue culture infective doses each of simian-human immunodeficiency virus KU-1B (SHIVKU-1B) (15), SHIV89.6P (12), and SIV 17E-Fr (SIV/17E-Fr) (5). The choice of the challenge virus was based on the ability of a mixture of these three viruses to induce uniform disease in a relatively short time (7). In other studies, where we used a single virus in the challenge inoculum, some of the animals required approximately 2 years before they developed clinical AIDS (6, 14). Another reason for using a mixture of three viruses was that we wanted to determine the effect of morphine addiction on virus replication in the cerebral compartment in a model system wherein all animals lose circulating CD4+ T cells. Two SHIVs used in this study are known to cause precipitous loss in CD4+ T cells in the blood, and SIV/17E-Fr is known to cause AIDS-related neurological disorders. These animals were monitored for a period of 12 weeks. The animals were bled at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 postinfection, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 postinfection. The animals were maintained on morphine throughout the observation period and monitored for CD4 profile and viral load in the plasma as well as in the CSF.

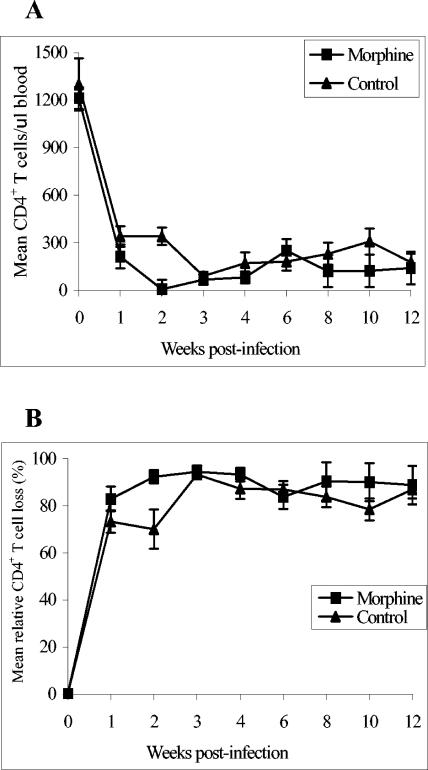

Circulating CD4+-T-cell levels were determined by staining for CD3, CD4, and CD8 surface markers. Approximately 105 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were stained with 10 μl of a mixture of antibodies against CD3, CD4, and CD8. The unbound antibodies were removed by washing the cells with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde and analyzed with a FACScalibur. The mean CD4+-T-cell counts and mean relative percentages of CD4+-T-cell loss are shown in Fig. 1. The week 0 mean CD4+-T-cell counts were 1,213 ± 69 and 1,300 ± 164 cells/μl of blood in the morphine and control groups, respectively. After infection, animals in both groups experienced massive CD4+-T-cell loss. However, at week 2 this loss was more pronounced in the morphine group (97 ± 59 and 341 ± 134 cells/μl of blood in morphine and control groups, respectively; P = 0.04). At other time points there were no significant differences in the CD4+-T-cell levels between the two groups.

FIG. 1.

Mean CD4+-T-cell profile (A) and mean relative loss in CD4+ T cells (B) in morphine-treated (n = 6) and control (n = 6) macaques. The percentage of CD4+ T cells was determined by staining with a mixture of antibodies against CD3, CD4, and CD8. The absolute number CD4+ T cells per microliter of blood was calculated by multiplying the percentage of the lymphocyte subset by the absolute number of lymphocytes per microliter of blood from the complete blood count. The mean relative loss in CD4+ T cells was calculated by considering the percentage of preinfection CD4+-T-cell counts as 100%. The results are presented as means ± standard errors.

The cell-associated viral loads in PBMC were determined in the infectious-cell assay by inoculation of serial 10-fold dilutions of PBMC into a culture of CEMx174 cells that were then observed for the development of cytopathic effects (CPE). Comparable infected cells were observed in all 12 animals, suggesting that there was no difference in the frequency of infected PBMC between the two groups (results not shown). The presence of infectious virus in CSF was determined in two different assays. The CSF was spun at 2,000 rpm (805 × g) for 10 min. The supernatant was separated from an invisible pellet. The pellet and 100 μl of CSF supernatant were cocultured with CEMx174 cells, and the presence of CPE was observed over a 1-week period. The virus-induced CPE was present in both groups. However CPE numbers were consistently higher in the morphine group animals (results not shown). Though this assay was designed only to determine the presence of the infectious virus in CSF, increased CPE frequency in morphine-dependent animals suggests the presence of more replication-competent virus in the cerebral compartments of morphine-addicted animals.

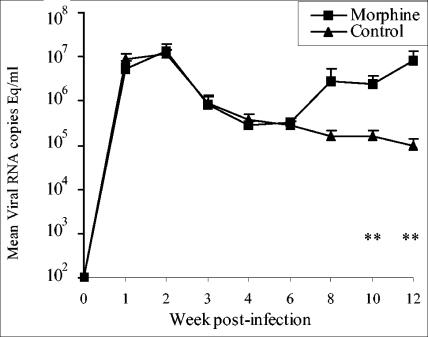

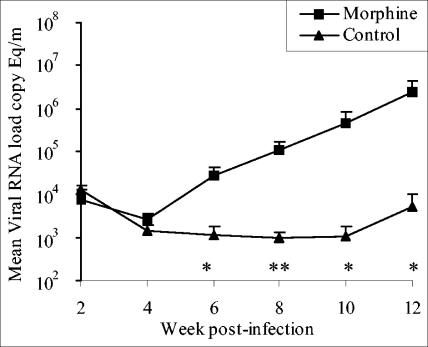

The viral loads in plasma and CSF were determined in duplicate by using a real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay (2). The RNA copy number was determined by comparison with an external standard curve consisting of in vitro transcripts representing bases 211 to 2101 of the SIVmac239 genome. This assay has a sensitivity of ≤80 copies/ml of plasma or CSF. The results of mean viral RNA loads in plasma are shown in Fig. 2. The control and morphine groups showed comparable peak viral loads at week 2 postinfection (1.37 × 107 ± 5.5 × 106 and 1.13 × 107 ± 2.69 × 106 RNA copy equivalents/ml of plasma in morphine and control groups, respectively). Furthermore both groups showed a gradual decline in the plasma viral loads over the next 4 weeks, and the viral loads during the first 6 weeks after infection were indistinguishable. However, the intensity of viral replication increased after week 6 in the morphine group compared to the control group, where the level of virus replication showed a marginal decline. The morphine group showed 18-, 15, and 87 (P = 0.05)-fold higher plasma viral load at weeks 8, 10, and 12, respectively. In view of the fact that some of the challenge viruses have shown the ability to induce AIDS-associated neurological problems, we monitored viral loads in the cerebral compartment by determining RNA quantity in CSF. The results of CSF viral loads in morphine and control groups are shown in Fig. 3. The two groups showed comparable viral loads until week 4 postinfection. The control group showed a gradual decline in the CSF viral loads until week 10, after which they showed fivefold increase at week 12. In contrast, the morphine group showed a consistent increase in CSF viral load, and viral replication in the cerebral compartment for the morphine group was 24-, 112-, 457-, and 454-fold higher than that in the control group at weeks 6, 8, 10, and 12, respectively. This difference was significant in Student's t test.

FIG. 2.

Mean plasma viral RNA loads in morphine-treated and control rhesus macaques. The viral RNA loads were determined by real-time RT-PCR. The results are presented as means ± standard errors. The statistical significance was calculated by Student's t test. **, P ≤ 0.05.

FIG. 3.

Mean viral loads in CSF collected from morphine-treated and control macaques. The viral RNA loads were determined by real-time RT-PCR. The results are presented as means ± standard errors. The statistical significance was calculated by Student's t test. *, P ≤ 0.1; **, P ≤ 0.05.

This is first demonstration of morphine-mediated enhanced viral replication in SIV or SHIV-infected rhesus macaques during the early phase of the infection and disease. Although the morphine-dependent animals showed comparable peak viral load, the viral set points in plasma in these animals were higher than those in the controls. Furthermore, this study also showed enhanced viral replication in the brain, suggesting that the adverse effect of morphine on viral replication occurred not only systemically but also in the cerebral compartment. This study also addresses the issues not addressed by earlier studies, i.e., adequate number of animals and presence of internal controls (4, 16). The reason for delayed adverse effect of morphine on virus replication in an earlier study (16) can be attributed to the choice of the challenge virus. The earlier study utilized SIVmac239, a virus that does not cause CD4+-T-cell loss until late-stage infection. The absence of CD4+-T-cell loss might help the morphine-dependent macaques mount an effective immune response, which could have kept the virus in check until more than 2 years after infection. While our model does not provide an exact replica of HIV infection in humans, it nevertheless demonstrates CD4+-T-cell loss. However, the loss is significantly higher than that seen during natural infection with HIV. In this study it is possible that early CD4+-T-cell loss, which was higher in morphine group at 2 weeks postinoculation, might have set the stage for the higher viral set points observed in these animals. The protective effect of morphine in another earlier study can be explained by the choice of the challenge virus (SIVsmm9) (4). This virus not only lacks the ability to cause CD4+-T-cell loss during the early phase of infection but also causes self-contained infection in at least one-half of the rhesus macaques.

The direct correlation between morphine dependence and viral replication has been attributed to CCR5 expression in the lymphocytes (16). This could also provide a basis for the higher viral set point in morphine group in the present study. There may be another possibility, i.e., that morphine-dependent macaques failed to develop virus-specific responses or might have developed ones inferior to those in the control animals. Experiments are under way to determine virus-specific immune responses in these animals.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Janice E. Clements, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md., and Norm L. Letvin, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass., for providing us SIV/17E-Fr and SHIV89.6P, respectively. We also thank Charles Sharp, NIDA, NIH, Bethesda, Md., for continuous discussions.

This work was supported by a grant from National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA015013).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcabes, P., and G. Friedland. 1995. Injection drug use and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:1467-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amara, R. R., F. Villinger, J. D. Altman, S. L. Lydy, S. P. O'Neil, S. I. Staprans, D. C. Montefiori, Y. Xu, J. G. Herndon, L. S. Wyatt, M. A. Candido, N. L. Kozyr, P. L. Earl, J. M. Smith, H. L. Ma, B. D. Grimm, M. L. Hulsey, J. Miller, H. M. McClure, J. M. McNicholl, B. Moss, and H. L. Robinson. 2001. Control of a mucosal challenge and prevention of AIDS by a multiprotein DNA/MVA vaccine. Science 292:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brancato, V., G. Delvecchio, and P. Simone. 1995. Survival and mortality in a cohort of heroin addicts in 1985-1994. Minerva Med. 86:97-99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donahoe, R. M., L. D. Byrd, H. M. McClure, P. Fultz, M. Brantley, F. Marsteller, A. A. Ansari, D. Wenzel, and M. Aceto. 1993. Consequences of opiate-dependency in a monkey model of AIDS. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 335:21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaherty, M. T., D. A. Hauer, J. L. Mankowski, M. C. Zink, and J. E. Clements. 1997. Molecular and biological characterization of a neurovirulent molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 71:5790-5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar, A., J. D. Lifson, Z. Li, F. Jia, S. Mukherjee, I. Adany, Z. Liu, M. Piatak, D. Sheffer, H. M. McClure, and O. Narayan. 2001. Sequential immunization of macaques with two differentially attenuated vaccines induced long-term virus-specific immune responses and conferred protection against AIDS caused by heterologous simian human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV(89.6)P). Virology 279:241-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar, A., S. Mukherjee, J. Shen, S. Buch, Z. Li, I. Adany, Z. Liu, W. Zhuge, M. Piatak, Jr., J. Lifson, H. McClure, and O. Narayan. 2002. Immunization of macaques with live simian human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) vaccines conferred protection against AIDS induced by homologous and heterologous SHIVs and simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology 301:189-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leshner, A. I. 1999. Drug abuse research helps curtail the spread of deadly infectious diseases. Natl. Inst. Drug Abuse Notes 14:3-4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metzger, D. S., G. E. Woody, A. T. McLellan, C. P. O'Brien, P. Druley, H. Navaline, D. DePhilippis, P. Stolley, and E. Abrutyn. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in- and out-of-treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 6:1049-1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyagi, T., L. F. Chuang, R. H. Doi, M. P. Carlos, J. V. Torres, and R. Y. Chuang. 2000. Morphine induces gene expression of CCR5 in human CEMx174 lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:31305-31310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierson, T., J. McArthur, and R. F. Siliciano. 2000. Reservoirs for HIV-1: mechanisms for viral persistence in the presence of antiviral immune responses and antiretroviral therapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:665-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reimann, K. A., J. T. Li, R. Veazey, M. Halloran, I. W. Park, G. B. Karlsson, J. Sodroski, and N. L. Letvin. 1996. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 70:6922-6928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selwyn, P. A., P. Alcabes, D. Hartel, D. Buono, E. E. Schoenbaum, R. S. Klein, K. Davenny, and G. H. Friedland. 1992. Clinical manifestations and predictors of disease progression in drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 327:1697-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverstein, P. S., G. A. Mackay, S. Mukherjee, Z. Li, M. Piatak, Jr., J. D. Lifson, O. Narayan, and A. Kumar. 2000. Pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV(KU) inoculated into immunized macaques caused infection, but virus burdens progressively declined with time. J. Virol. 74:10489-10497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh, D. K., C. McCormick, E. Pacyniak, D. Griffin, D. M. Pinson, F. Sun, N. E. Berman, and E. B. Stephens. 2002. Pathogenic and nef-interrupted simian-human immunodeficiency viruses traffic to the macaque CNS and cause astrocytosis early after inoculation. Virology 296:39-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki, S., A. J. Chuang, L. F. Chuang, R. H. Doi, and R. Y. Chuang. 2002. Morphine promotes simian acquired immunodeficiency syndrome virus replication in monkey peripheral mononuclear cells: induction of CC chemokine receptor 5 expression for virus entry. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1826-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]