Abstract

Rotavirus assembly is a multistep process that requires the successive association of four major structural proteins in three concentric layers. It has been assumed until now that VP4, the most external viral protein that forms the spikes of mature virions, associates with double-layer particles within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in conjunction with VP7 and with the help of a nonstructural protein, NSP4. VP7 and NSP4 are two glycosylated proteins. However, we recently described a strong association of VP4 with raft-type membrane microdomains, a result that makes the ER a highly questionable site for the final assembly of rotavirus, since rafts are thought to be absent from this compartment. In this study, we used tunicamycin (TM), a drug known to block the first step of protein N glycosylation, as a tool to dissect rotavirus assembly. We show that, as expected, TM blocks viral protein glycosylation and also decreases virus infectivity. In the meantime, viral particles were blocked as enveloped particles in the ER. Interestingly, TM does not prevent the targeting of VP4 to the cell surface nor its association with raft membranes, whereas the infectivity associated with the raft fractions strongly decreased. VP4 does not colocalize with the ER marker protein disulfide-isomerase even when viral particles were blocked by TM in this compartment. These results strongly support a primary role for raft membranes in rotavirus final assembly and the fact that VP4 assembly with the rest of the particle is an extrareticular event.

Rotaviruses, which are the leading cause of infantile diarrhea worldwide, are nonenveloped viruses belonging to the Reoviridae family. The capsid of rotavirus is composed of three concentric layers of proteins surrounding a segmented double-stranded RNA genome (reviewed in reference 9). The glycoprotein VP7 constitutes, with the spike protein VP4, the outermost layer. VP7 is an integral endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident membrane protein (16). VP4 is synthesized on free ribosomes, and it has been assumed that this protein is directly released within the cytosol.

During the virus life cycle, mostly studied in MA 104 cells, double-layered particles (DLPs) are assembled in cytoplasmic inclusions called viroplasms. DLPs are then translocated from these structures into the adjacent ER. During this process, which is mediated by the interaction of DLPs with the ER transmembrane protein NSP4, the particles acquire a transient membrane envelope (1). Once this envelope is lost, the mature particles containing VP7 and VP4 appear (10). This maturation step involves calcium (30) and protein glycosylation (24, 28, 31, 34). The step at which VP4 is assembled is not clear. VP4 has been localized between the periphery of the viroplasm and outside the ER (29). VP4 is also present on the cell surface and along cytoskeletal structures early after infection (26; A. Gardet, S. Chwetzoff, and G. Trugnan, unpublished data). A juxtanuclear localization of VP4 similar to that of NSP4 and VP7 has also been described (12). It has been proposed that VP4 forms hetero-oligomeric complexes with NSP4 and VP7 (19) and assembles with DLPs together with VP7 inside the ER. However, triple-layered particles containing VP7 are assembled in cells in which VP4 synthesis was inhibited through a short interfering RNA (siRNA) approach (7).

Virus release from MA 104 cells is associated with the concomitant lysis of infected cells. In clear contrast, in Caco-2 cells, a well-polarized and differentiated intestinal cell line, rotavirus is released from the apical surface through a nonconventional pathway that bypasses the Golgi apparatus (15). We have recently shown that rafts would be involved in this atypical pathway (32). Rafts are membrane microdomains enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids and are thought to play a key role in apical trafficking of epithelial cells (33). The sphingolipids, which constitute the backbone of rafts, are only synthesized in the Golgi apparatus of mammalian cells (37). In rotavirus-infected Caco-2 cells, we showed that an important proportion of VP4 rapidly associates with lipid rafts and is early targeted to the apical membrane. Later on, other structural viral proteins and viral infectivity also cosegregate with the raft fractions (32). Very recently, Cuadras and Greenberg (5) confirmed that rotavirus infectious particles use lipid rafts during replication for transport to the cell surface in vitro and in vivo. These results led us to propose that lipid rafts may serve as a platform for the final step of virus assembly when VP4 associates with the rest of the particle. Since lipid rafts are not supposed to be present in the ER, we proposed that this final assembly step takes place in an extrareticular compartment.

The drug tunicamycin (TM) is an inhibitor of the first step of protein glycosylation, known to occur within the ER. In MA 104 cells infected with rotavirus, this drug has been shown to block viral particles as enveloped particles in the ER compartment (34) and to decrease rotavirus infectivity in MA 104 cells (28, 31). Mirazimi et al. (23) observed that treatment with TM causes misfolding of VP7 protein, leading to inter-disulfide bond aggregation. In this work, we showed that treatment of Caco-2 cells with TM led to an expected inhibition of VP7 and NSP4 glycosylation that was associated with the accumulation of enveloped particles within large ER vesicles. Accordingly, we observed a strong decrease in the ability of Caco-2 cells to produce infectious particles. The number of infectious virions was decreased in the whole-cell homogenate as well as in raft fractions. Interestingly, VP4 expression, trafficking, and localization were essentially unaffected by TM treatment. In particular, there was no change in the cell surface targeting of VP4 nor in its association with rafts. More importantly, we were unable to localize VP4 within classical ER structures with or without TM treatment, whereas VP7 was detected in this compartment. These results strongly suggest that the final rotavirus assembly is an extrareticular event.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies.

The primary antibodies used were as follows: rabbit polyclonal anti-RF antiserum (8148), which recognizes viral structural proteins; mouse monoclonal anti-VP4 (7.7); mouse monoclonal antibody anti-VP7 (M60) (22); mouse monoclonal anti-NSP4 (120-147), which was a gift from M. Estes; mouse monoclonal anti-protein disulfide-isomerase (anti-PDI), purchased from StressGen (Victoria, Canada); and goat anti-actin (I-19), purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). The secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence were fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) and rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1, which were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Peroxidase-conjugated antibodies used for Western blotting were goat anti-mouse (Rockland, Gilbertsville, Pa.) or goat anti-rabbit (Sigma-Aldrich). Finally, for flow cytometry, donkey anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Cy5 and donkey anti-goat IgG conjugated to FITC antibodies were both purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Baltimore, Md.).

Cell infection and treatment.

Caco-2 cells (passages 50 to 70) obtained from ECACC (Salisbury, United Kingdom) were infected at 21 days postseeding with rotavirus strain RF obtained from J. Cohen (CNRS, Gif sur Yvette, France) as previously described (32). When present, TM was added at the beginning of the postinfection time from a stock solution of 5 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide. Titers of infectious virus release in culture medium from Caco-2 cells were determined by plaque assay on MA 104 cells (15). Cell homogenates were prepared in TNE (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) containing 1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 and antiproteases (complete minitablets from Roche Diagnostics). Gradient separation was performed by flotation on a sucrose gradient (32). To determine infectivity in the raft fractions, homogenates were prepared in TNC (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2). TNC was also used to perform the sucrose gradient separation. For immunofluorescence analysis, cells grown on coverslips were incubated for 45 min at room temperature with, sequentially, anti-PDI antibody, followed by rhodamine-conjugated anti-IgG1 antibody, then 7.7 or M60 antibodies, and FITC-conjugated anti-IgG2a antibody. Proteins from homogenates or recovered from gradients were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies, and revealed with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham). Films were digitized, and bands were quantified with Scion Image software.

Flow cytometry.

Analysis by flow cytometry was performed with cells detached with trypsin EDTA. To prevent permeabilization, cells were treated on ice and primary antibodies were added to cells before fixation. Cells were incubated with anti-VP4 (7.7) and anti-actin for 1 h. After washes, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and then incubated with secondary antibodies (anti-mouse Cy5 and anti-goat FITC). Cells were washed between each step with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin. When cells were permeabilized, all steps were performed at room temperature. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and then treated with 0.075% saponin. All antibody solutions also contained saponin. Mock-infected cells were incubated with the 7.7 antibody and both secondary antibodies as a negative control. Fluorescence and light scatters were analyzed in a BD Biosciences fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACSCalibur) equipped with an argon laser tuned at 488 nm and a 635-nm diode, and Cell Quest software was used for acquisition. Ten thousand cells were analyzed for each sample.

Electron microscopy.

Cells were rinsed three times with PBS and were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and 1.5% osmium tetroxide in sodium phosphate buffer for 30 min at room temperature. After being washed with PBS, they were scrapped and postfixed for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a Jeol JEM-1010 electron microscope.

RESULTS

TM inhibited glycosylation of viral proteins and prevented formation of mature particles in polarized Caco-2 cells. (i) Inhibition of viral protein glycosylation.

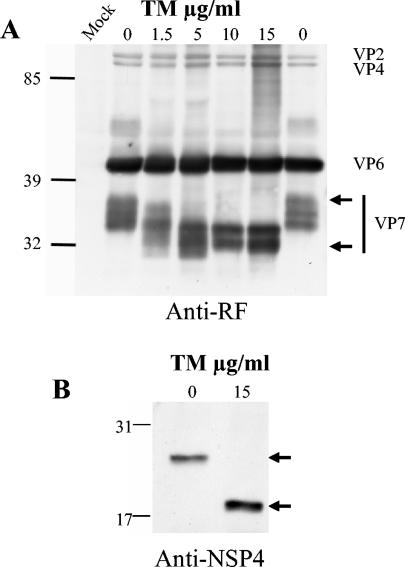

Monolayers of Caco-2 cells, cultured for 21 days such that their phenotype corresponded to that of an intestinal epithelium (6), were infected with trypsin-activated rotavirus strain RF at a multiplicity of infection of 10 PFU/cell. After 1 h, infection medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing TM at the indicated concentrations. Cell media were collected, and cells were homogenized at 18 h postinfection (hpi). Viral proteins were analyzed from cell lysates by Western blotting. Using polyclonal anti-RF antibody, VP7 appeared as a series of at least three bands ranging from 40 to 35 kDa. Using TM at a classical concentration of 1.5 μg/ml, the higher bands were significantly affected suggesting that they likely correspond to glycosylated VP7 (Fig. 1A). These bands completely disappeared when cells were treated with 10 and 15 μg of TM. Concurrently, a new lower band that likely corresponds to unglycosylated VP7 appeared at 32 kDa (Fig. 1A). The amount and migration of the other viral structural proteins, VP2, VP4, and VP6, were not modified by the drug at any TM concentration. NSP4, a nonstructural protein, was revealed as a single band by using a monoclonal antibody. The glycosylation of NSP4 was also completely blocked in the presence of 15 μg of TM (Fig. 1B), thus confirming that TM was fully active under these conditions.

FIG. 1.

TM inhibited VP7 and NSP4 glycosylation. VP7 and NSP4 glycosylation were analyzed by Western blotting. (A) Confluent Caco-2 cells were infected with 10 PFU for 1 h. Infection media were removed and replaced with fresh media containing TM at the indicated concentrations. Cells were scraped at 18 hpi and homogenized, and the viral proteins were immunoblotted with anti-RF polyclonal antibody. The positions of viral structural proteins are indicated. Arrows indicate the position of glycosylated (upper) and unglycosylated (lower) VP7. Mock, noninfected cells. (B) Cells were treated as described for panel A, and proteins were immunoblotted with an anti-NSP4 antibody (120-147). The upper arrow indicates the glycosylated form of NSP4, and the lower arrow indicates the unglycosylated form of NSP4.

(ii) Inhibition of rotavirus release and association with rafts.

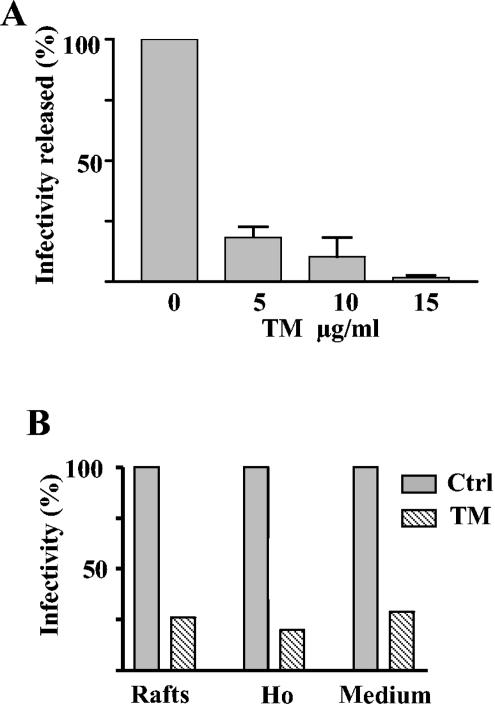

We next investigated whether glycosylation impairment of viral proteins was associated with a decrease in infectivity. We quantified the effect of TM on the formation of infectious particles by assaying their capacity to lyse MA 104 cells in a plaque assay. Media from infected Caco-2 cells treated with increasing TM concentrations were analyzed at 18 hpi for their content in infectious particles. As seen in Fig. 2A, in the presence of 5 μg of TM, the release of infectious rotavirus particles was reduced by 83%. Infectivity was further reduced up to 97% when TM was increased to 15 μg/ml.

FIG. 2.

TM inhibited infectious rotavirus production in Caco-2 cells. (A) Infectious virus production was analyzed from infected Caco-2 cells treated with the indicated amounts of TM. Culture media collected at 18 hpi were frozen, thawed, and then assayed for virus titration by plaque assay on MA104 cells. Values are means ± standard deviations of the results from two different experiments and are expressed as percentages of nontreated cells (mean infectivity of non-TM-treated cells, 6.4 × 106 ± 0.6 × 106 PFU per ml). (B) Results from a typical experiment comparing the effect of 10 μg of TM/ml on the infectivity present in the homogenate (Ho), in the raft fraction, and released in the medium is shown. The homogenate prepared in TNC-1% Triton X-100 and the raft fraction isolated after flotation on a sucrose gradient were prepared as described in Material and Methods. The homogenate and raft fraction were diluted in infection medium and assayed for virus titration. Values are expressed as percentages of those of the controls (ctrl) (control raft, 5.8 × 106 PFU per ml; control homogenate, 3.5 × 109 PFU per ml; control medium, 2.2 × 106 PFU per ml).

Infectious viral particles were previously shown to be released from the apical pole of Caco-2 cell monolayers and to be present on raft membranes, which could account for their apical targeting (5, 32). We therefore studied the effect of TM on the association of infectious virions with rafts. Rafts were prepared by flotation on a sucrose gradient of Caco-2 cells treated with 1% Triton X-100 in the absence or presence of TM. Rafts were collected in one fraction, and their infectivity was assayed by plaque assay. TM considerably reduced the infectivity associated with the raft fraction. We also quantified the total infectivity of cell homogenate. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 2B, this infectivity was reduced to the same extent as in the raft fraction and in the released material. These results showed that TM was able to block rotavirus release and raft association and suggested that rotavirus assembly was impaired.

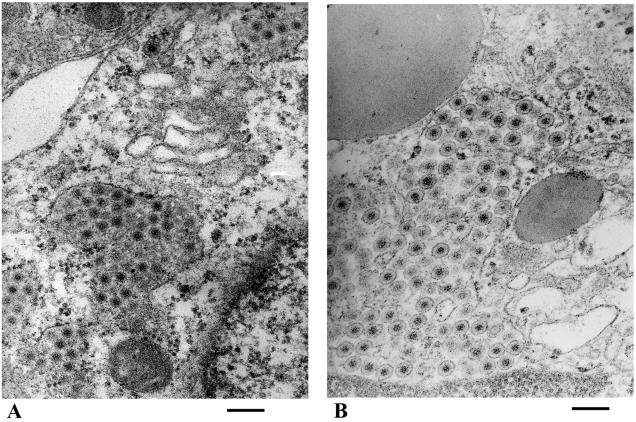

(iii) TM blocked virus particles as enveloped particles.

We therefore investigated, by using electron microscopy, whether the virus was fully matured in TM-treated cells. Neovirions were effectively blocked at the stage of enveloped particles, as shown in Fig. 3. Most particles were seen as enveloped particles within dilated and clear structures surrounded by some ribosomes in TM-treated cells (Fig. 3B). In contrast, in control cells, virions appeared as nonenveloped particles within smaller and more dense vesicles (Fig. 3A). These data confirmed that TM was able to block rotavirus morphogenesis at the same step in Caco-2 and MA 104 cells (8, 23, 31).

FIG. 3.

TM blocked viral particles as enveloped particles. Caco-2 cells were infected and not treated (A) or treated (B) with 15 μg of TM/ml for 24 hpi. Large concentrations of enveloped particles can be observed in TM-treated cells, and nonenveloped particles in smaller and denser structures are present in control cells. Bars, 200 nm.

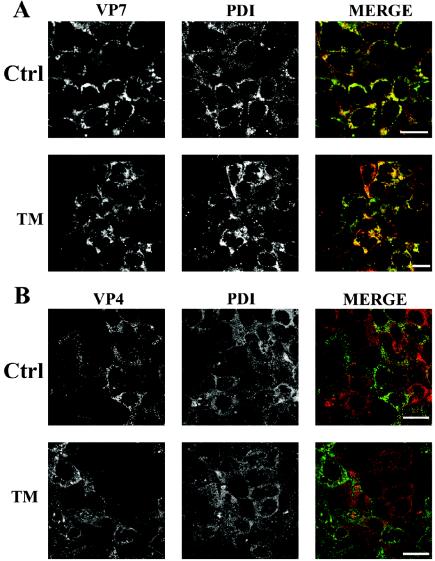

TM did not induce VP4 to accumulate in the ER.

The above results indicated that TM blocked rotavirus morphogenesis in the ER of Caco-2 cells. We therefore addressed the question of whether VP4 was already present in these immature particles. This was investigated by confocal microscopy. Cells were immunostained with a monoclonal antibody against the ER marker PDI (11) and a monoclonal antibody against VP4. As a positive control, we analyzed the localization of VP7, an ER resident viral protein. The colocalization between VP7 and PDI was obvious in control cells as well as in TM-treated cells (Fig. 4A). In contrast, we were unable to show any significant colocalization between VP4 and PDI in both control and TM-treated cells (Fig. 4B). It should be pointed out that VP4 and PDI were almost never located on the same confocal plane, a result that explains the apparent heterogeneity of the staining. Together, these experiments indicated that TM was unable to relocate VP4 within the ER, although the drug leads to an accumulation of immature virions within this compartment.

FIG. 4.

VP7, not VP4, colocalizes with PDI. Infected Caco-2 cells were not treated (ctrl) or treated with 10 μg of TM/ml for 18 hpi. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, double stained by indirect immunofluorescence, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. VP7 was stained with the monoclonal antibody M60. The ER marker PDI was stained with a monoclonal antibody (StressGen). Confocal acquisitions were performed on the entire cell depth, and only one section that corresponds to the middle of the cell is displayed. Left panel, VP7 (green channel); middle panel, PDI (red channel); right panel, merged image of both signals. (B) Cells were treated as described for panel A, and VP4 was stained with the monoclonal antibody 7.7. Bars, 20 μm.

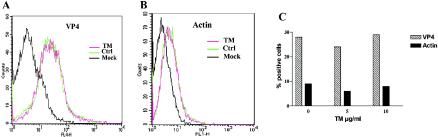

TM did not perturb the apical membrane targeting of VP4.

It was previously shown that VP4 was targeted to the apical surface of Caco-2 cells (32) through atypical trafficking, bypassing the Golgi apparatus (15). To investigate whether TM modified the targeting of VP4 to the cell surface, we quantified the presence of VP4 at the plasma membrane of nonpermeabilized Caco-2 cells by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 5A, the number of cells expressing VP4 at the cell surface, in both control and TM-treated cells, was quite identical. The results shown in Fig. 5C indicate that around 30% of the total cell population expressed VP4 at the cell surface. This represented about half of the infected cells, as determined by the number of VP4-positive cells after cell permeabilization. It should be noted that Caco-2 cells were treated on ice all throughout fixation and antibody treatments to prevent permeabilization. Actin staining was used as a control for permeabilization and demonstrated that infection indeed induced a slight permeabilization of Caco-2 cells (Fig. 5B). However, TM did not modify infection-induced permeabilization that never concerned more than 8% of Caco-2 cells, as shown in Fig. 5C. These data clearly indicated that TM had no effect on VP4 targeting to the cell surface.

FIG. 5.

TM did not prevent VP4 association with the cell surface. Cell surface expression of VP4 (A) was analyzed by flow cytometry, with actin used as a control for cell permeabilization (B). Caco-2 cells that were noninfected (Mock), infected (Ctrl), or infected and treated with 10 μg of TM/ml (TM) were fixed at 18 hpi and immediately treated with antibodies. All treatments were performed on ice. In panel C, surface labeling is expressed as the percentage of positive cells in nonpermeabilized Caco-2 cells relative to the total number of analyzed cells. The results shown are from one experiment representative of four independent experiments.

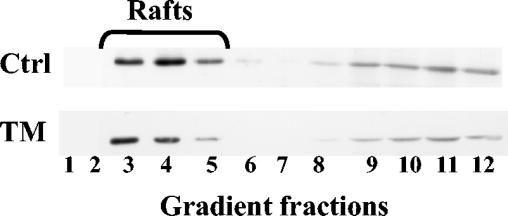

TM did not modify VP4 association with rafts.

Since we previously assumed that VP4 surface expression was dependent on its raft association, we checked whether TM was able to interfere with this process. To investigate the effect of TM on the association of VP4 with rafts, control and TM-treated Caco-2 cells were treated with 1% Triton X-100 at 18 hpi, and the resulting homogenates were separated on a sucrose gradient. Proteins from the 12 gradient fractions were separated by electrophoresis and immunoblotted with anti-VP4 antibody. As seen in Fig. 6, 33% of VP4 protein floated in fractions 3, 4, and 5 in control and TM-treated Caco-2 cells. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments. These results indicated that TM was unable to interfere with raft-associated VP4, whereas, as shown in Fig. 2B, the drug was able to strongly decrease the amount of mature viral particles associated with rafts.

FIG. 6.

TM did not prevent VP4 association with isolated rafts. Rafts were prepared by flotation on a sucrose gradient from Triton X-100-resistant membranes of infected Caco-2 cells nontreated (Ctrl) or treated with 10 μg of TM/ml (TM), as indicated in Materials and Methods. Twelve fractions were collected from gradients. The same amounts of fractions were loaded and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Western blots were revealed with 7.7 anti-VP4 antibody. Typically, the percentage of VP4 present in the rafts was around 33%.

Together, these experiments indicated that TM, a drug that mainly perturbs ER glycosylation, blocked rotavirus morphogenesis without affecting the intracellular fate of VP4.

DISCUSSION

How and where the rotavirus spike protein VP4 is assembled with the rest of the particle is still a matter of debate. It has been proposed that VP4 associates with the viral particles together with VP7 in an NSP4-dependent process within the ER (19). However, this model is challenged by experimental data indicating that VP4 was present within raft microdomains (5, 32) which are thought to be excluded from the ER (37). In addition, there was until now no clear demonstration that VP4 localized within the ER (12). To further investigate these points, we decided to use TM, a drug known to interfere with ER glycosylation and previously used to block rotavirus maturation in MA 104 cells (31, 34). Our idea was that if VP4 assembled with viral particles in the ER, then TM should affect its trafficking, localization, and raft association. In this study, we demonstrated that the fate of VP4 remains mainly independent of TM treatment, whereas the drug blocked the maturation of viral particles in the ER. It should, however, be mentioned that higher concentrations of TM were needed in Caco-2 cells than in MA 104 cells. Virus production was reduced by 99% with less than 1 μg of TM in MA 104 cells (31), whereas about 10 to 15 μg was needed to reduce the amount of infectious virus released from Caco-2 cells by 95 to 97%. The limitation of drug penetration in this tightly packed epithelial cell line endowed with a dense apical brush border could account for these differences, as previously observed (21). Anyway, by treating Caco-2 cells with 10 μg of TM, the glycosylation of viral proteins was inhibited and particles were blocked in the ER as enveloped particles. VP4 was still present at the plasma membrane, associated with rafts, and did not accumulate in the ER.

Our results clearly show that VP7 and NSP4 glycosylation is impaired upon TM treatment. Data from the literature suggest that VP7 glycosylation could be of little importance for virus assembly. Indeed, rotavirus strains with no VP7 glycosylation (29) or with one or two glycosylation sites on VP7 (10, 17) have been shown to assemble and produce fully infectious particles. The nonstructural protein NSP4 has been implicated, in MA 104 cells, when double-shelled particles bud within the ER and become enveloped. Its glycosylation is critical for the removal of the transient envelope (28). It is likely that NSP4 glycosylation is also involved in the removal of the envelope in Caco-2 cells, since we observed a complete deglycosylation of this protein that could affect its function. It is noteworthy that the blockage of immature particles as enveloped ones in the ER can be observed after cell treatment with a Ca2+ ionophore (30). Since NSP4 was shown to mobilize Ca2+ from the ER (35), the inhibition of NSP4 glycosylation could prevent Ca2+ mobilization by NSP4 and thus block the particles in the ER. However, it cannot be ruled out that the glycosylation of cellular proteins or lipids may be part of the explanation. This last hypothesis has to be further documented.

Anyway, we observed a large accumulation of particles surrounded by a clearly defined membrane. These enveloped particles appeared to be retained in the ER as shown by the presence of ribosomes on these membranes. Concomitantly, TM inhibited the release of infectious particles from Caco-2 cells. However, neither the targeting of VP4 to the cell surface nor the association of VP4 with rafts was modified by the drug, demonstrating that the fate of VP4 was independent of the accumulation of immature viral particles within the ER. The presence of VP4 on the cell surface of MA 104 cells (26) and at the apical pole of Caco-2 cells (32) has already been observed. In this study, analysis by flow cytometry clearly showed that TM did not prevent VP4 trafficking to the cell surface. It is of interest that only 50% of infected cells expressed VP4 on their surface. This can be accounted for by the fact that Caco-2 cells are known to behave as mosaic cells, expressing a set of brush border hydrolases in an uncoordinated way (36). It is therefore likely that interactions of rotavirus and rotaviral protein with these cells depends on the actual panel of cell surface-expressed proteins and will vary from one cell to another. The presence of VP4 on rafts of Caco-2 cells is well documented. VP4 was shown to resist short-term treatment with Triton X-100 in vivo (32) and was recovered within rafts isolated by flotation (5, 32). Our data show that TM does not change the amount of VP4 recovered with the raft fraction. In contrast, TM considerably decreased the amount of infectious particles associated with rafts. The fact that this decrease observed in rafts was of the same order of magnitude as the decrease of released infectious particles strengthens our hypothesis of the primary role of rafts in the apical sorting of rotavirus particles. Further studies are in progress to visualize viral particles and viral proteins within this raft fraction by using electron and cryoelectron microscopy approaches and to examine in more detail how TM interferes with rotavirus final assembly.

We show here that the blockage of viral particles as enveloped particles in dilated ER cisternae does not induce VP4 to accumulate in the regions where VP7 colocalized with PDI. VP4 was first localized between the periphery of the viroplasm and outside the ER (29). Hetero-oligomeric complexes of VP7, NSP4, and VP4 were then proposed to participate in the budding of double-shelled particles through the ER membrane (19). Consistent with the formation of such complexes, Gonzalez et al. (12), using double immunostaining and confocal microscopy, observed some overlapping between VP4, VP7, and NSP4. However, they demonstrated recently that invalidation of VP4 through an siRNA approach does not prevent the formation of triple-layered particles containing VP7 and not VP4 (7). Accordingly, we show here that in TM-treated cells as well as in control cells, VP4 never colocalized with the ER marker PDI, which is an abundant ER protein (11).

It is then likely that VP4 assembly with the rest of the particle occurs in an extrareticular space. The ER Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) may be a good candidate, considering that NSP4 accumulates in a post-ER compartment and redistributes ERGIC markers (38) and that VP7 is supposed to pass by a post-ER compartment for its final maturation (17, 23). However, VP4 is recovered essentially associated with lipid rafts. It is well known that the sphingolipids which constitute the backbone of rafts are only synthesized in the Golgi apparatus of mammalian cells (37). Consequently, sphingolipids can only be delivered to the ER through a retrograde pathway. Brugger et al. (4) observed that the amount of sphingomyelin present in coat protein COP-I retrograde transport vesicles was very low compared to the Golgi content. However, the sphingomyelin of COP-I vesicles was enriched in stearoyl species (4). This favors the hypothesis of a particular subset of rafts present in ERGIC that could be involved in rotavirus assembly.

Alternatively, final rotavirus assembly might occur in a post-Golgi compartment. NSP4 interacts preferentially with raft model membranes (14). It was shown to associate with rafts in Caco-2 cells (5, 32). Contact sites between the ER and the trans-Golgi network have recently been observed in mammalian cells (18, 20) and could provide the opportunity for the reticular protein NSP4 to come in contact with rafts. NSP4 would then drive the other structural proteins to fuse with VP4-containing rafts.

Our results also point to the fact that VP4 may join the particle after VP7 assembly. Dector et al. (7) observed that upon siRNA-mediated invalidation of VP4, particles containing VP7 and not VP4 can assemble. Surprisingly, the spikeless particles show a larger diameter (∼90 nm) than particles containing VP4 (∼80 nm). This suggests that VP7 may assemble before VP4 on maturing viral particles. The VP7 layer presents large channels in which preassembled VP4 (dimers or trimers) may enter. This would induce interactions between VP4, VP7, and possibly VP6, resulting in subtle conformational changes leading to particle condensation.

Elucidation of the targeting of VP4 to the cell surface would help to clarify where and at which step of the virus cycle the final assembly occurs. VP4 is lacking any conventional signal peptide in the secretory pathway and, as a cytosolic protein, does not follow the classical vesicular trafficking route through the ER-Golgi compartments. Such unconventional protein sorting, which concerns a number of cellular proteins, was discovered more than 10 years ago and remains not well understood (27). Recently, a role for rafts in Golgi-independent secretion of cytosolic proteins, such as galectin-4 (2, 13) and Hsp 70 (3), and in Golgi-independent targeting of membrane proteins, such as flotillin-1 (25), has been proposed. VP4, which associates with rafts as soon as it is synthesized, is likely to follow this pathway and constitutes a good tool for studying the mechanisms of this uncharacterized cellular route.

Acknowledgments

We thank Philippe Fontanges who took care of the confocal microscope and Tounsia Aït Slimane for help in confocal microscopy. We also thank Michel Kornprost for assistance in flow cytometry analysis.

This work was supported by grants from ACI microbiology, by ITM INSERM, and by grants from the research ministry of France (PRFMMIP).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altenburg, B. C., D. Y. Graham, and M. K. Estes. 1980. Ultrastructural study of rotavirus replication in cultured cells. J. Gen. Virol. 46:75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braccia, A., M. Villani, L. Immerdal, L. L. Niels-Christiansen, B. T. Nystrom, G. H. Hansen, and E. M. Danielsen. 2003. Microvillar membrane microdomains exist at physiological temperature. Role of galectin-4 as lipid raft stabilizer revealed by “superrafts.” J. Biol. Chem. 278:15679-15684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broquet, A. H., G. Thomas, J. Masliah, G. Trugnan, and M. Bachelet. 2003. Expression of the molecular chaperone Hsp70 in detergent-resistant microdomains correlates with its membrane delivery and release. J. Biol. Chem. 278:21601-21606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brugger, B., R. Sandhoff, S. Wegehingel, K. Gorgas, J. Malsam, J. B. Helms, W. D. Lehmann, W. Nickel, and F. T. Wieland. 2000. Evidence for segregation of sphingomyelin and cholesterol during formation of COPI-coated vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 151:507-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuadras, M. A., and H. B. Greenberg. 2003. Rotavirus infectious particles use lipid rafts during replication for transport to the cell surface in vitro and in vivo. Virology 313:308-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darmoul, D., M. Lacasa, L. Baricault, D. Marguet, C. Sapin, P. Trotot, A. Barbat, and G. Trugnan. 1992. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD 26) gene expression in enterocyte-like colon cancer cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2. Cloning of the complete human coding sequence and changes of dipeptidyl peptidase IV mRNA levels during cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 267:4824-4833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dector, M. A., P. Romero, S. Lopez, and C. F. Arias. 2002. Rotavirus gene silencing by small interfering RNAs. EMBO Rep. 3:1175-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ericson, B. L., D. Y. Graham, B. B. Mason, and M. K. Estes. 1982. Identification, synthesis, and modifications of simian rotavirus SA11 polypeptides in infected cells. J. Virol. 42:825-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estes, M. K. 2001. Rotaviruses and their replication, p. 1747-1785. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 10.Estes, M. K., and J. Cohen. 1989. Rotavirus gene structure and function. Microbiol. Rev. 53:410-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari, D. M., and H. D. Soling. 1999. The protein disulphide-isomerase family: unravelling a string of folds. Biochem. J. 339:1-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez, R. A., R. Espinosa, P. Romero, S. Lopez, and C. F. Arias. 2000. Relative localization of viroplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum-resident rotavirus proteins in infected cells. Arch. Virol. 145:1963-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen, G. H., L. Immerdal, E. Thorsen, L. L. Niels-Christiansen, B. T. Nystrom, E. J. Demant, and E. M. Danielsen. 2001. Lipid rafts exist as stable cholesterol-independent microdomains in the brush border membrane of enterocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:32338-32344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, H., F. Schroeder, C. Zeng, M. K. Estes, J. K. Schoer, and J. M. Ball. 2001. Membrane interactions of a novel viral enterotoxin: rotavirus nonstructural glycoprotein NSP4. Biochemistry 40:4169-4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jourdan, N., M. Maurice, D. Delautier, A. M. Quero, A. L. Servin, and G. Trugnan. 1997. Rotavirus is released from the apical surface of cultured human intestinal cells through nonconventional vesicular transport that bypasses the Golgi apparatus. J. Virol. 71:8268-8278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabcenell, A. K., and P. H. Atkinson. 1985. Processing of the rough endoplasmic reticulum membrane glycoproteins of rotavirus SA11. J. Cell Biol. 101:1270-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabcenell, A. K., M. S. Poruchynsky, A. R. Bellamy, H. B. Greenberg, and P. H. Atkinson. 1988. Two forms of VP7 are involved in assembly of SA11 rotavirus in endoplasmic reticulum. J. Virol. 62:2929-2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladinsky, M. S., D. N. Mastronarde, J. R. McIntosh, K. E. Howell, and L. A. Staehelin. 1999. Golgi structure in three dimensions: functional insights from the normal rat kidney cell. J. Cell Biol. 144:1135-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maass, D. R., and P. H. Atkinson. 1990. Rotavirus proteins VP7, NS28, and VP4 form oligomeric structures. J. Virol. 64:2632-2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsh, B. J., D. N. Mastronarde, K. F. Buttle, K. E. Howell, and J. R. McIntosh. 2001. Organellar relationships in the Golgi region of the pancreatic beta cell line, HIT-T15, visualized by high resolution electron tomography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2399-2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meerson, N. R., V. Bello, J. L. Delaunay, T. A. Slimane, D. Delautier, C. Lenoir, G. Trugnan, and M. Maurice. 2000. Intracellular traffic of the ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase NPP3 to the apical plasma membrane of MDCK and Caco-2 cells: apical targeting occurs in the absence of N-glycosylation. J. Cell Sci. 113:4193-4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirazimi, A., M. Nilsson, L. Svensson, and C. H. von Bonsdorff. 1998. The molecular chaperone calnexin interacts with the NSP4 enterotoxin of rotavirus in vivo and in vitro. Carbohydrates facilitate correct disulfide bond formation and folding of rotavirus VP7. J. Virol. 72:8705-8709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirazimi, A., L. Svensson, and C. H. von Bonsdorff. 1998. Carbohydrates facilitate correct disulfide bond formation and folding of rotavirus VP7. J. Virol. 72:3887-3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirazimi, A., C. H. von Bonsdorff, and L. Svensson. 1996. Effect of brefeldin A on rotavirus assembly and oligosaccharide processing. Virology 217:554-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrow, I. C., S. Rea, S. Martin, I. A. Prior, R. Prohaska, J. F. Hancock, D. E. James, and R. G. Parton. 2002. Flotillin-1/reggie-2 traffics to surface raft domains via a novel golgi-independent pathway. Identification of a novel membrane targeting domain and a role for palmitoylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48834-48841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nejmeddine, M., G. Trugnan, C. Sapin, E. Kohli, L. Svensson, S. Lopez, and J. Cohen. 2000. Rotavirus spike protein VP4 is present at the plasma membrane and is associated with microtubules in infected cells. J. Virol. 74:3313-3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nickel, W. 2003. The mystery of nonclassical protein secretion. A current view on cargo proteins and potential export routes. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:2109-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrie, B. L., M. K. Estes, and D. Y. Graham. 1983. Effects of tunicamycin on rotavirus morphogenesis and infectivity. J. Virol. 46:270-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrie, B. L., H. B. Greenberg, D. Y. Graham, and M. K. Estes. 1984. Ultrastructural localization of rotavirus antigens using colloidal gold. Virus Res. 1:133-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poruchynsky, M. S., D. R. Maass, and P. H. Atkinson. 1991. Calcium depletion blocks the maturation of rotavirus by altering the oligomerization of virus-encoded proteins in the ER. J. Cell Biol. 114:651-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabara, M., L. A. Babiuk, J. Gilchrist, and V. Misra. 1982. Effect of tunicamycin on rotavirus assembly and infectivity. J. Virol. 43:1082-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sapin, C., O. Colard, O. Delmas, C. Tessier, M. Breton, V. Enouf, S. Chwetzoff, J. Ouanich, J. Cohen, C. Wolf, and G. Trugnan. 2002. Rafts promote assembly and atypical targeting of a nonenveloped virus, rotavirus, in Caco-2 cells. J. Virol. 76:4591-4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simons, K., and D. Toomre. 2000. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki, H., T. Sato, T. Konno, S. Kitaoka, T. Ebina, and N. Ishida. 1984. Effect of tunicamycin on human rotavirus morphogenesis and infectivity. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 81:363-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian, P., Y. Hu, W. P. Schilling, D. A. Lindsay, J. Eiden, and M. K. Estes. 1994. The nonstructural glycoprotein of rotavirus affects intracellular calcium levels. J. Virol. 68:251-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vachon, P. H., N. Perreault, P. Magny, and J. F. Beaulieu. 1996. Uncoordinated, transient mosaic patterns of intestinal hydrolase expression in differentiating human enterocytes. J. Cell Physiol. 166:198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Meer, G., and Q. Lisman. 2002. Sphingolipid transport: rafts and translocators. J. Biol. Chem. 277:25855-25858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu, A., A. R. Bellamy, and J. A. Taylor. 2000. Immobilization of the early secretory pathway by a virus glycoprotein that binds to microtubules. EMBO J. 19:6465-6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]