Abstract

We have previously studied B cells, from people and mice, that express rotavirus-specific surface immunoglobulin (RV-sIg) by flow cytometry with recombinant virus-like particles that contain green fluorescent protein. In the present study we characterized circulating B cells with RV-sIg in children with acute and convalescent infection. During acute infection, circulating RV-sIgD− B cells are predominantly large, CD38high, CD27high, CD138+/−, CCR6−, α4β7+, CCR9+, CCR10+, cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-negative (CLA−), L-selectinint/−, and sIgM+, sIgG−, sIgA+/− lymphocytes. This phenotype likely corresponds to gut-targeted plasma cells and plasmablasts. During convalescence the phenotype switches to small and large lymphocytes, CD38int/−, CD27int/−, CCR6+, α4β7+/−, CCR9+/− and CCR10−, most likely representing RV-specific memory B cells with both gut and systemic trafficking profiles. Of note, during acute RV infection both total and RV-specific murine IgM and IgA antibody-secreting cells migrate efficiently to CCL28 (the CCR10 ligand) and to a lesser extent to CCL25 (the CCR9 ligand). Our results show that CCR10 and CCR9 can be expressed on IgM as well as IgA antibody-secreting cells in response to acute intestinal infection, likely helping target these cells to the gut. However, these intestinal infection-induced plasmablasts lack the CLA homing receptor for skin, consistent with mechanisms of differential CCR10 participation in skin T versus intestinal plasma cell homing. Interestingly, RV memory cells generally lack CCR9 and CCR10 and instead express CCR6, which may enable recruitment to diverse epithelial sites of inflammation.

Rotavirus (RV) is the principal cause of severe diarrhea in young children worldwide, causing approximately 352,000 to 592,000 deaths a year (32). In animals and humans, it has been shown that intestinal immunoglobulin A (IgA) plays an important role in protection from reinfection (10, 13, 38). A detailed characterization of the B cells that produce this intestinal IgA will be useful for future studies of immunogenicity and protective efficacy of RV vaccines (12).

Recently, we described a flow cytometry assay that allowed us to study circulating B cells that express RV-specific surface Ig (RV-sIg) (14, 37). RV-sIg cells were identified with recombinant virus-like particles (VLPs) that contain green fluorescent protein (GFP). VLPs fail to bind to nonimmune murine B cells and bind at very low frequency to B cells from noninfected children or adults, conferring high specificity to this assay (14, 37). In human studies we found a correlation between large IgD− B cells that express RV-sIg and RV-specific antibody-secreting cells (ASC) during acute but not convalescent RV infection (14). This suggested that the lymphocytes detected by flow cytometry during acute infection and subsequently in convalescence were RV ASC and memory B cells, respectively.

It has been shown that different subsets of B cells, corresponding to different stages of differentiation and maturation, can be identified according to the presence or absence of several surface markers. For example, the expression of high levels of CD38 (CD38high) versus intermediate or negative levels (CD38int/−) distinguishes circulating ASC from circulating memory B cells (16, 28). The peripheral blood CD38high B-cell population of ASC can be further divided into plasma cells or plasmablasts based on the presence or absence of CD138 expression (16, 33). Although less studied than CD38, CCR6 and CD27 have also been shown to be differentially expressed on ASC and memory cells (1, 21, 31).

An important finding from our previous human studies was that the cells that express RV-sIg predominantly express the integrin α4β7 (14). This observation supports the hypothesis that circulating RV-sIg B cells have been primed in and are trafficking back to the intestine (7). Thus, the flow cytometry-based assay enhances our ability to indirectly measure intestinal RV ASC, which are presumably responsible for protection. In addition to α4β7, recent studies have shown that the chemokines TECK/CCL25 (thymus-expressed chemokine) and MEC/CCL28 (mucosa-associated epithelial chemokine) and their respective receptors, CCR9 and CCR10, play an important role in the process of B-cell homing to the gut (24, 26, 39). CCL25 is almost exclusively expressed in the small intestine and attracts B cells that express CCR9 and IgA on their surfaces.

Recently, it was demonstrated that RV-specific IgA ASC induced after enteric infection preferentially migrate to CCL25 (4). Additionally, B cells that express CCR9 on their surfaces are rare in the colon and absent in other epithelial tissues, and for this reason it has been proposed that CCL25 and CCR9 may serve to compartmentalize the small intestine immune response (23). In contrast, CCL28 is expressed in a variety of epithelial tissues, including the salivary gland, mammary gland, small and large intestine, tonsil, appendix, and trachea, and it has been shown that CCR10 is selectively expressed on IgA ASC (24, 26). The current hypothesis is that the CCL28-CCR10 interaction functions as a unifying mucosal homing program for IgA ASC (23).

In the present study, we sought to determine if IgD−, RV- sIg B cells circulating in young children during the acute and convalescent phases of RV infection have the phenotypes of ASC and memory B cells, respectively, and express other (distinct from the previously evaluated α4β7) receptors consistent with an intestinal trafficking program. For this purpose we evaluated the expression of surface markers of maturation (CD38, CD27, CD138, and CCR6), the expression of receptors involved in intestinal (CCR9, CCR10), skin (cutaneous lymphocyte antigen [CLA]), and peripheral lymph node (L-selectin) trafficking, and finally the expression of sIg isotypes on these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and sample collection.

We studied 10 children (age range, 7 to 18 months) admitted with acute RV diarrhea of less than 7 days of duration to the Lucile Packard Children's Hospital (Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, Calif.) and 39 children (age range, 5 to 30 months) that were seen at the San Ignacio Hospital (Bogotá, Colombia). We collected blood and stool samples from 37 patients during the acute phase (from 1 to 9 days after the onset of diarrhea) of RV disease and from 20 patients during the convalescent phase (10 to 43 days after the onset of diarrhea). Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the children, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board committee of Stanford University and the Ethics committee of the San Ignacio Hospital.

The presence of RV antigen in feces was determined with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously described (14) or a commercial kit (Rotaclone; Meridian Diagnostics, Cincinnati, Ohio).

Lymphocyte isolation and B-cell purification.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient with Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia). Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) plus 2% fetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL). Cells were then resuspended in PBS containing 2 mM EDTA (Sigma Aldrich) plus 10% fetal calf serum. Immunomagnetic negative selection of B cells was performed with a B-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif.), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Production of fluorescent VLPs.

Production of fluorescent RV VLPs (GFP-VLPs) with baculovirus expression vectors was done as previously described (8). Briefly, Sf9 cells were coinfected with two recombinant baculoviruses at a multiplicity of infection greater than 5 PFU/cell. One was a baculovirus-expressed RF (bovine RV) VP6, and the other was a fusion protein consisting of GFP fused to the N terminus of RF or rhesus RV VP2 deleted in the first 92 amino acids (35). Infected cultures were collected 5 to 7 days postinfection and purified by density gradient centrifugation in CsCl. The protein concentration in the purified GFP-VLPs was estimated by the method of Bradford.

Cell staining and flow cytometry analysis.

Negatively isolated B cells (5 × 105) were incubated with GFP-VLPs for 45 min in the dark at 4°C. Then the cells were washed with PBS-0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma)-0.02% sodium azide (Mallinckrodt Chemicals, Paris, Ky.) (staining buffer) and stained with different combinations of monoclonal antibodies against the following human proteins: α4β7 phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibody Act-1, mouse IgG1 (Charles Mackay Leukosite Inc., Cambridge, Mass.); purified CCR10 monoclonal antibody 1B5, mouse IgG2a (Millenium Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cambridge, Mass.); purified CCR9 monoclonal antibody 96-1, mouse IgG1 (Millenium Pharmaceuticals); purified CCR6 monoclonal antibody 53103, mouse IgG2b (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.); and purified CD38 monoclonal antibody HB7, mouse IgG1 (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.). These purified antibodies were then detected with goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chain)-allophycocyanin (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.).

Unconjugated isotype controls were obtained from Sigma. Directly conjugated mouse anti-CD27-phycoerythrin monoclonal antibody M-T271, IgA1/2-biotin monoclonal antibody G20-359, IgM-phycoerythrin monoclonal antibody G20-127, IgG-phycoerythrin monoclonal antibody G18-145, purified anti-CD62 ligand (all mouse IgG1), and anti-CLA biotin monoclonal antibody HECA-452, rat IgM, were from BD Pharmingen (La Jolla, Calif.). Anti-CD38-allophycocyanin and anti-CD38 phycoerythrin (monoclonal antibody HIT2, mouse IgG1) were from BD Pharmingen. IgD-biotin (monoclonal antibody IADB6, mouse IgG2a) and goat anti-IgA (α chain)-phycoerythrin were from Southern Biotechnology Inc. (Birmingham, Ala.). Anti-CD138 phycoerythrin (IgG1) was from Immunotech (Marseille, France). The biotinylated antibodies were detected with streptavidin-PerCP (BD Pharmingen). After staining, the cells were washed once with staining buffer and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Washington, Pa.).

In order to determine the purity of the negatively selected B cells, they were stained with anti-CD19-allophycocyanin (Pharmingen) and anti-CD3-PerCP (BD Pharmingen). The efficiency of B-cell negative selection was measured with flow cytometry with a mean purity of 92.6% ± 0.5% and 91.5% ± 0.8 during acute and convalescent phases, respectively.

At least 50,000 cells were acquired, and four-color flow cytometry was done on a FACSCalibur (BD Pharmingen) and analyzed with Cellquest software, version 3.1. Dead cells were excluded by forward and side scatter gating.

Mice and viral infection.

Mouse lymphocytes were used only in the experiments to study chemotaxis of RV-specific ASC (Fig. 10); all other studies used human B cells.

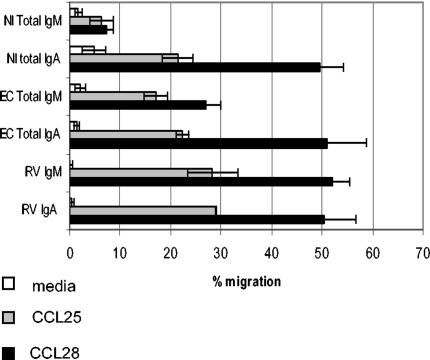

FIG. 10.

Migration of RV IgM and IgA ASC to CCL25 and CCL28. Lymphocytes from the mesenteric lymph nodes of RV-infected (EC, day 10 postinfection) and noninfected (NI) mice were allowed to migrate to medium, CCL25, and CCL28. The responding RV IgA and IgM ASC and total IgA and IgM ASC were detected by Elispot. Data are shown as means ± standard errors of the means for at least three experiments for each condition. Migration to CCL25 and CCL28 in each condition was significantly above migration to medium (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test).

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Six- to 8-week-old mice were inoculated by gastric gavage with 104 50% shedding dose (SD50)/mouse of murine (EC) RV after receiving 100 μl of 1.33% sodium bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid. Mice were sacrificed 10 days after infection for chemotaxis experiments.

Chemotaxis assay.

Lymphocytes from mesenteric lymph nodes were isolated by mechanical disruption through a wire mesh. Lymphocytes were allowed to recover in RPMI-10% fetal calf serum for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 before chemotaxis. Migration assays were performed as previously described (26). Briefly, 2 × 106 lymphocytes were placed in the upper chamber of 5-μm Transwell inserts (Corning Costar, Cambridge, Mass.), and the inserts were placed in wells with medium alone (basal) or medium containing 300 nM murine CCL25 or 250 nM murine CCL28. Chemokines were obtained from R&D Systems and used at the concentrations shown previously to be optimal for chemotaxis (26). After 2 h, the inserts were removed, and multiple replicate chemotaxis wells were combined for Elispot analysis.

Elispot assays.

Elispot assays for detection of RV ASC and total IgM or IgA ASC were performed as previously described (37). Briefly, nitrocellulose 96-well plates (Multiscreen 96-well filtration plate; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) were coated overnight at 4°C with cesium-purified rhesus RV or goat anti-mouse IgM- or IgA-specific polyclonal antibodies (Kirkegaard & Perry, Gaithersburg, Md.) or sterile PBS. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2, removed, and the captured Ig was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA or IgM (Kirkegaard & Perry). Spots formed by individual ASC were visualized by adding the precipitating peroxidase substrate 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Vector, Burlingame, Calif.) for 30 min. The number of ASC per well was determined by counting the spots under a dissecting microscope. The efficiency of migration was calculated by comparing the number of spots present in the input population with the number of spots present in the migrated population. Background (nonspecific) ASC were subtracted from RV-specific ASC.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software version 9.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.). Differences between groups were evaluated with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Significance was established if P was <0.05. Data are shown as mean and standard error of the mean unless otherwise noted.

RESULTS

Frequencies of CD38high (ASC) and CD38int/− (memory) RV-sIg IgD− B cells in children with RV infection.

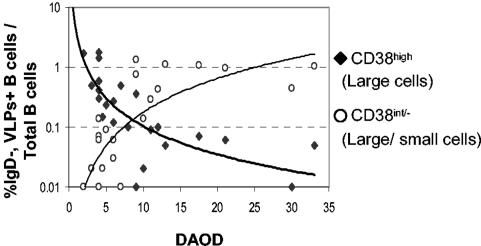

To determine if B cells that express RV-sIg (cells that stained with the GFP-VLPs) during acute infection and convalescence have the phenotype of ASC or memory cells, we first studied expression of CD38. For this purpose, B cells were microbead isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of 23 children infected with RV from 2 to 33 days after the onset of diarrhea and stained with monoclonal antibodies against IgD, CD38, and GFP-VLPs. Since only large (probably blasts) but not small cells were CD38high, we performed our analysis on large cells that expressed CD38high and on large and small cells that expressed CD38int/−. The analysis was done on IgD− B cells because most of IgD+ B cells are thought to be non-antigen experienced (34).

Within 2 days after the onset of diarrhea, substantial numbers of CD38high B cells were detectable, while CD38int/− were only present at low frequencies (Fig. 1). As time passed, the CD38high population decreased and the CD38int/− increased. Prior to 9 days after the onset of diarrhea, the frequency of RV-sIg large CD38high cells predominated over that of CD38int/− large and small B cells (Fig. 1). After this time point this relationship reversed. For this reason, we considered the acute phase of infection up to 9 days after the onset of diarrhea and concluded, based on CD38 expression, that most IgD−, RV-sIg B cells in the acute and convalescent phases of the disease have the phenotypes of ASC and memory B cells, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Frequencies of RV-sIg (GFP-VLP+) purified B cells with the phenotype of antibody-secreting cells (CD38high, large) and memory B cells (CD38int/−, large and small) as a function of days after the onset of diarrhea in RV-infected children (n = 23). B cells were purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by negative selection with magnetic beads, stained with monoclonal antibodies against IgD, CD38, and GFP-VLPs, and assayed by flow cytometry. The results are expressed as the percentage of each subpopulation relative to the number of total B cells of each child. Lines represent potential best-fit curves at R2 = 0.6 (bold line) and R2 = 0.56 (regular line) for CD38high and CD38int/− cells, respectively.

Maturation markers on total and RV-sIg large B cells in children during acute infection and convalescence.

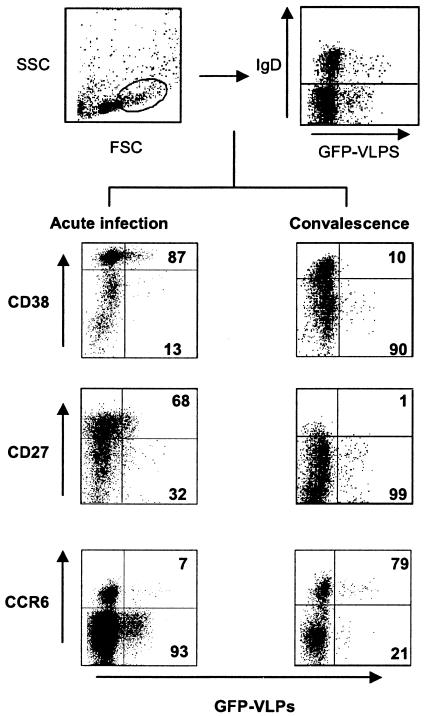

To extend the results with CD38, we next evaluated B cells from children for the expression of two additional markers, CCR6 (21, 24) and CD27 (1, 31), that have also been proposed to be differentially expressed on ASC and memory B cells. For comparison, the frequencies of IgD− B cells expressing each marker were analyzed on both total and RV-specific populations. Figure 2 shows representative dot plots from experiments of CD38, CD27, and CCR6 expression on IgD− large B cells from children during acute RV infection and convalescence. The mean fluorescence intensity of the GFP-VLPs was lower on the cells from the acute phase than on those from the convalescent phase (P = 0.001) (Fig. 2 and data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Representative flow cytometry analysis of large IgD− B cells from acutely infected children (left lower dot plots) and children in convalescence (right lower dot plots) for the expression of the indicated maturation markers. B cells were negatively selected with magnetic beads and then stained with monoclonal antibodies against IgD, α4β7, CD38, CD27, or CCR6 and with GFP-VLP. For analysis, cells were gated on large (top left dot plot), IgD− (top right dot plot) lymphocytes. Based on this subpopulation, the lower dot plots were created showing expression of CCR6, CD38, and CD27 and GFP-VLP fluorescence. The percentages of IgD− GFP-VLP+ (RV-sIg) cells expressing each marker are indicated in the right quadrants.

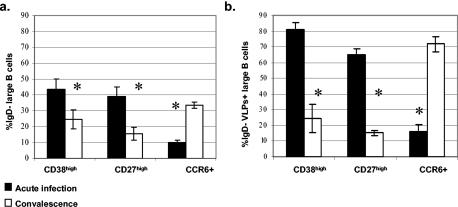

The mean results of the percentage of total and antigen-specific IgD− B cells expressing each marker during acute and convalescent diarrheal episodes are presented in Fig. 3. For total IgD− B cells, during the acute phase, 43.6% ± 6.1% were CD38high, 39% ± 2.4% were CD27high and 9.8% ± 1.7% expressed CCR6. During convalescence the frequency of CD38high diminished significantly to 24.3% ± 5.9% (P = 0.001), as did the expression of CD27high (15.6%, ± 4.0%) (P = 0.01). In contrast, the frequency of CCR6 significantly increased in convalescence to 33.4% ± 1.9% (P = 0.001). For RV-sIg B cells the changes between cells during the acute and convalescent phases were more pronounced than those seen in total IgD− B cells (Fig. 3a versus 3b). We found that during acute infection 80.9% ± 4.5% of the large IgD−, RV-sIg lymphocytes were CD38high and that this percentage decreased significantly during convalescence to 24.4% ± 9.1% (P = 0.001).

FIG. 3.

Mean and standard error of the mean of IgD− (a) and IgD− RV-sIg (b) large B cells that express the maturation markers CD38high, CD27high and CCR6 in children during acute infection (n = 6 to 12 children) and convalescence (n = 4 to 8 children). The frequencies of cells expressing each marker in individual children were obtained as described for Fig. 2. *, significant differences between acute infection and convalescence for each marker (P < 0.01, Mann-Whitney test).

A similar pattern of expression was observed for CD27high B cells, 64.9% ± 5.7% being positive during the acute phase, while only 15.1% ± 1.8% were IgD−, RV-sIg, CD27high during convalescence (P = 0.01). In contrast, only a small percentage of the large IgD−, RV-sIg B cells were CCR6+ during the acute phase (16.1% ± 4.5%), but the expression of CCR6 increased substantially during convalescence (71.9% ± 4.7%, P = 0.001) (Fig. 3b). The decrease in CD38high and CD27high expression and increase of CCR6 expression during the late phase of the infection are compatible with the differentiation process from ASC to memory B cells (Fig. 3b).

In conclusion, during the acute phase most B cells with RV-sIg are CD38high, CD27high, CCR6− large B cells, a phenotype compatible with RV ASC. More than half of these cells (mean, 75.1% ± 9.4%, n = 5, data not shown) express CD138, suggesting that they are a mixture of plasma cells and plasmablasts (16). This subset of cells was detected almost exclusively during acute infection. During convalescence these cells change significantly to CD38int/−, CD27int/−, CCR6+ large and small B cells consistent with a memory B-cell phenotype.

Trafficking markers on total and RV-sIg large B cells following infection.

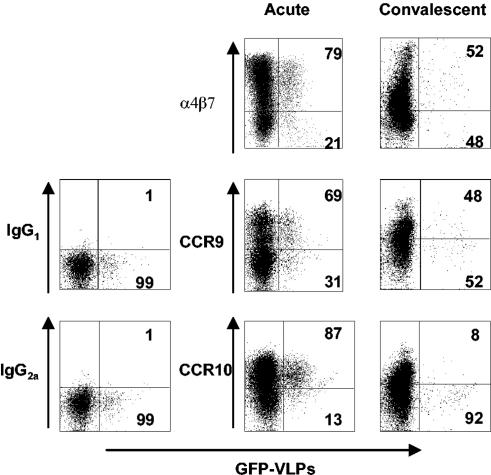

In the current model of B-cell trafficking to the intestine, both the homing receptor α4β7 and the chemokine receptors CCR9 and CCR10 are thought to play critical roles (22, 23). Since RV replicates predominantly in the small intestine and blood circulating RV-specific B cells are hypothesized to originate in Peyer's patches, we wanted to determine if these cells exhibit a gut-homing phenotype as evidenced by α4β7, CCR9, and CCR10 expression. Figure 4 shows representative dot plots of large IgD− B cells stained for α4β7, CCR9, and CCR10 during the acute and convalescent phases of infection, and the expression among all children is summarized in Fig. 5.

FIG. 4.

Representative flow cytometry analysis of large IgD− cells and the expression of indicated trafficking receptors in children during acute (left) and convalescent (right) phases. B cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies against IgD, α4β7, CCR9, or CCR10 and with GFP-VLPs. Analysis was done as in Fig. 2. Dot plots show expression of α4β7, CCR9, and CCR10 and GFP-VLP fluorescence. The percentages of IgD− GFP-VLP+ (RV-sIg) cells expressing each marker are indicated in the right quadrants.

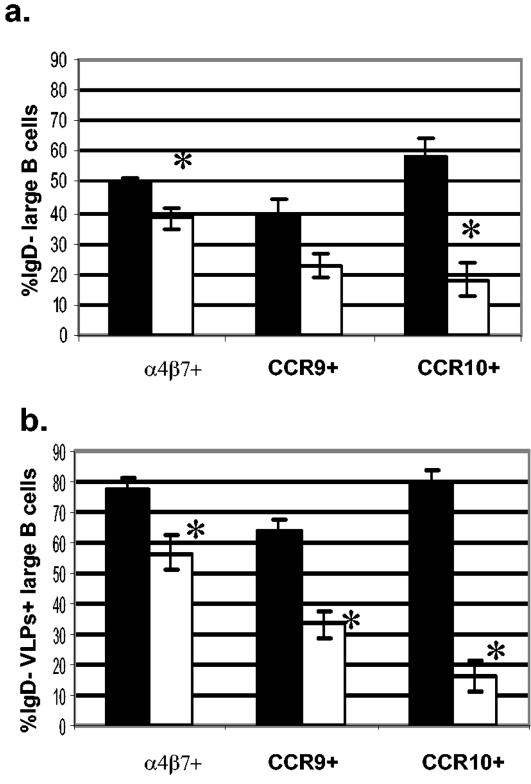

FIG. 5.

Mean and standard error of the mean of large, IgD− (a) and IgD− RV-sIg (b) B cells that express the homing markers α4β7, CCR9, and CCR10 in children during acute infection (n = 8 to 12 children) and convalescence (n = 5 to 7 children). The frequencies of cells expressing each marker in individual children were obtained as described for Fig. 4. *, significant differences between acute infection and convalescence for each marker (P < 0.006, Mann-Whitney test).

Analysis of expression of total (non-RV-specific, Fig. 5a) α4β7 large IgD− B cells showed that 49.7% ± 1.7% were α4β7+ during the acute phase, while during convalescence this frequency significantly decreased, to 38.1% ± 3.7% (P = 0.002). In addition, 39.2% ± 5.1% and 22.5% ± 4.1% of the total (non-RV-specific) large IgD− B cells expressed CCR9 during the acute and convalescence phases, respectively (P = 0.069). Finally, 58.3% ± 5.7% of cells were CCR10+ during acute infection, while the percentage of positive cells diminished significantly to 18.1% ± 4.7% during convalescence (P = 0.001) (Fig. 5a).

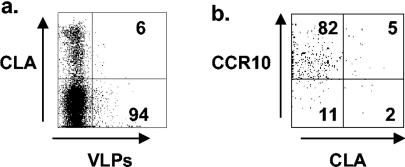

When RV-sIg B cells were examined, during the acute phase 77.8% ± 3.7%, 63.4% ± 4.4%, and 78.1% ± 5.3% of IgD− RV-sIg, large B cells (Fig. 5b) expressed α4β7, CCR9, and CCR10, respectively; all these percentages decreased significantly (P < 0.005) during convalescence to 56.8% ± 6.04%, 33.2% ± 4%, and 15.9% ± 3%, respectively (Fig. 5b). These results suggest that the great majority of RV-sIg+ cells with an ASC phenotype have been activated in the intestinal Peyer's patches and express all three gut-homing receptors, α4β7, CCR9, and CCR10. Further evidence for the intestinal commitment of these cells was provided by staining with antibodies against L-selectin and CLA, two molecules involved in homing to nonintestinal sites, namely, the peripheral lymph node and skin, respectively (7). Very few (mean, 8.1% ± 1.2, n = 4, and 2.6% ± 1.1, n = 3) of these cell expressed CLA (Fig. 6) and high levels of L-selectin, respectively. During convalescence, the RV-sIg memory B cells in the circulation had lower expression of the three homing receptors, with only 56% expressing α4β7 and 33% expressing CCR9. Of note, very few (<20%), if any, of the RV memory cells were CCR10+, consistent with the fact that CCR10 does not appear to be expressed by memory B cells (24).

FIG. 6.

Expression of CLA on large IgD− B cells and coexpression of CLA and CCR10 on large IgD− RV-sIg B cells. Dot plots from a representative experiment show expression of CLA on cells gated on large IgD− (a) and coexpression of CLA and CCR10 (b) on cells gated on large IgD− RV-sIg B cells from a child during acute infection. The percentages of cells in the quadrants are indicated.

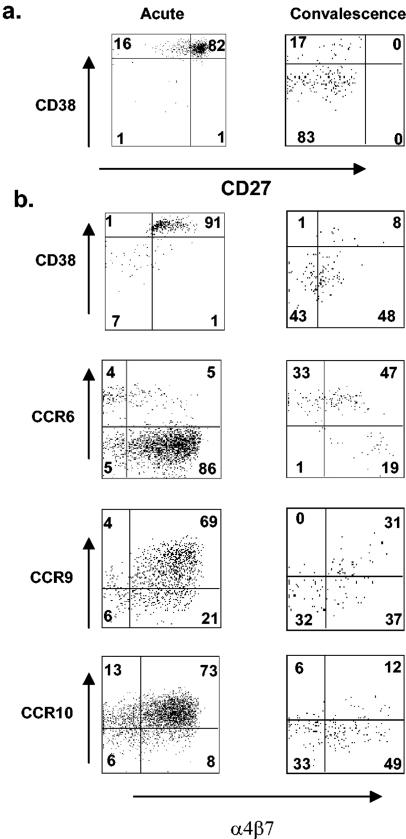

Coexpression of selected maturation and trafficking markers on RV-sIg B cells.

Our ability to identify purified RV-sIg, IgD− B cells allowed us to evaluate the coexpression of two separate markers. We first analyzed the coexpression of the maturation markers CD38 and CD27 in infected children during acute infection (n = 5) and convalescence (n = 2). Figure 7a shows a representative experiment from children during acute infection (left) and convalescence (right). We found that during the acute phase, most RV-sIg cells (mean, 83% ± 5.7%) coexpressed high levels of CD38 and CD27. Interestingly, a population coexpressing CD38high CD27int/− but not one corresponding to the reciprocal population, CD38int/− CD27high, was observed. In the convalescent phase the double positive population (CD38high CD27high) almost completely disappeared and the great majority (mean, 79% ± 4.5%) of cells were CD38int/− CD27int/−, most probably memory B cells. A small number of cells continued to express high levels of CD38 (24.4%).

FIG. 7.

Coexpression of maturation markers and trafficking receptors on large IgD− RV-sIg B cells. Shown are representative experiments of the study of the coexpression of CD38 and CD27 (a) and CD38, CCR6, CCR9, CCR10, and α4β7 (b) on large IgD− RV-sIg B cells from children during acute infection (left dot plots) and convalescence (right dot plots). Analysis was done with the basic strategy described for Fig. 2. Dot plots show expression of each indicated marker and/or receptor on cells with a gate on large IgD− RV-sIg B cells. The percentages of cells in all the quadrants are indicated.

We also analyzed the coexpression of CD38, CCR6, CCR9, and CCR10 with α4β7 in children during acute infection and convalescence (n = 5 to 11 acute and 4 to 7 convalescent). Figure 7b shows representative dot plots of the coexpression of the above mentioned markers during acute infection (left) and convalescence (right). On average, during the acute phase, most of the IgD−, RV-sIg, CD38high B cells also expressed surface α4β7 (73.5%,= ± 6.3%). The high level of coexpression of these two markers decreased during convalescence, when only 46.6% ± 5.4% of the IgD−, RV-sIg, CD38int/− were α4β7+. Interestingly, this last percentage is almost identical to the percentage that coexpress CCR6 and α4β7 (mean 52.8%, ± 3.6% in convalescent children). This similarity suggests that these represent the same cell population and implies that approximately half of the circulating RV-sIg memory B cells (CD38int/−, CCR6+) have gut-homing potential.

During acute infection 66.9% ± 4.1% and 68.1% ± 4.6% of the RV-sIg cells coexpressed CCR9 and CCR10 with α4β7+. This suggests that, during acute infection, RV-sIg B cells likely coexpress three surface receptors that allow them to efficiently migrate back to the intestine. During convalescence, when the great majority of RV-specific B cells are CCR6+, very few expressed CCR10, and these were equally divided between α4β7+ and α4β7− subsets. Furthermore, in convalescence, we could define three circulating subsets of RV-sIg cells based on the expression of CCR9 and α4β7: 27% ± 3.9% of the cells coexpressed CCR9+ and α4β7, 35.9% ± 3.1% were CCR9− α4β7+ cells, and 38.8% ± 4.3% were double negative CCR9− α4β7− cells. No cells expressed high levels of CCR9 in the absence of α4β7 expression.

Finally, we sought to evaluate the coexpression of CCR10 and CLA on RV-sIg cells during acute infection. The coexpression of these two receptors is of special interest, since CTACK/CCL27, the second known CCR10 ligand, is expressed by keratinocytes and therefore CCR10+ cells have the potential to home to the skin. As shown in Fig. 6b the great majority of RV-sIg cells (82%) are CCR10+ CLA−. This result suggests that although RV-sIg cells are CCR10+, they are unable to migrate to the skin.

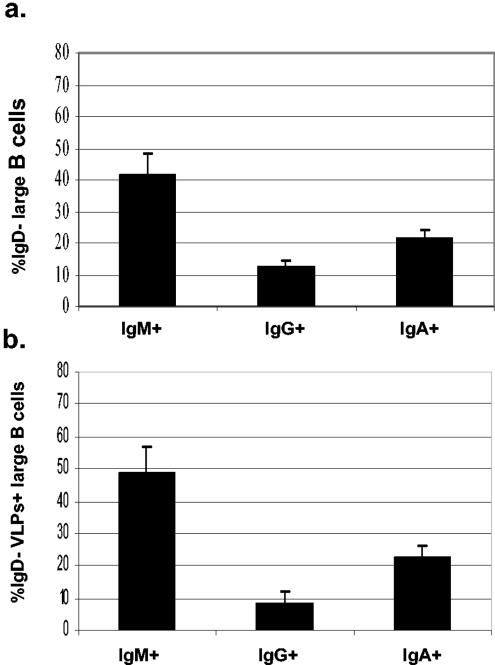

sIg isotype on RV-sIg B cells from children during acute infection.

To more fully characterize the RV-sIg B cells during acute infection, we determined their sIg isotype. Figure 8 shows the mean frequency of expression of each isotype (IgM, IgG, and IgA) for total sIg cells (Fig. 8a) and RV-sIg cells (Fig. 8b) from acutely infected children. The predominant isotype of total cells is sIgM (41.7% ± 6.8%), with lower percentages for sIgG (12.5% ± 1.8%) and sIgA (21.1% ± 3.1%). A similar distribution is observed for RV-sIg cells (IgM, 48.5% ± 8.4%, IgG, 8.3% ± 3.9% and IgA, 22.2% ± 3.6%). These results are consistent with previous data (14), where we found that in children with an acute RV infection, the total and virus-specific ASC determined by Elispot were mainly of the IgM isotype.

FIG. 8.

Mean and standard error of the mean of large, IgD− (a) and IgD− RV-sIg (b) B cells that express sIgA, sIgM, or sIgG in children during acute infection (n = 13, 7, and 5 for sIgA, sIgM, and sIgG, respectively). The frequencies of cells expressing each Ig isotype in individual children were obtained with the basic analysis strategy described for Fig. 2. This figure includes experiments with five children in which cells of the three isotypes could be measured simultaneously. If only the results from these five children were considered, a graph very similar to the one presented was obtained.

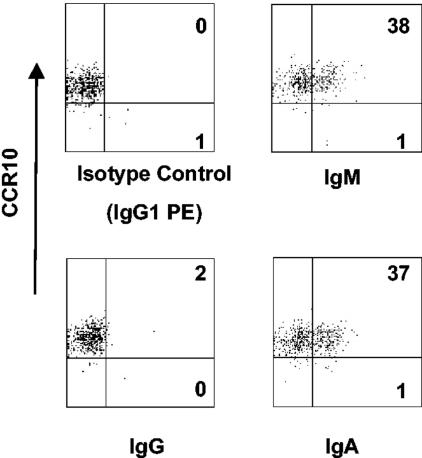

Preliminary experiments suggested that frequencies of isotype-switched RV-sIg B cells increase in cells from convalescent children. We also wanted to determine the coexpression of sIg with CCR10, the most polarized chemokine receptor for ASC. To do this, we costained cells for sIgM, sIgG, or sIgA and CCR10. Figure 9 shows dot plots from one representative experiment. CCR10+ RV-sIg cells predominantly coexpressed sIgM (37.6% ± 6.0%, n = 5), followed by sIgA (18.1% ± 5.7%, n = 5), with very few coexpressing sIgG (7.7% ± 3.6%, n = 4).

FIG. 9.

Flow cytometry analysis of large IgD−, RV- sIg B cells and coexpression of RV-sIg and CCR10 in children during acute infection. B cells were purified by negative selection with magnetic beads and stained with monoclonal antibodies against IgD, CCR10, sIgA, sIgM, or sIgG and GFP-VLPs. For analysis, cells were gated on large IgD−, RV-sIg (GFP-VLP+) cells, as described for Fig. 2, and dot plots showing the expression of each isotype and CCR10 were created. The percentages of cells in the right quadrants are indicated.

Chemotaxis of murine RV-specific IgA and IgM ASC induced during an acute RV infection.

The finding that RV-sIg cells from acutely infected children are predominantly CCR9+, CCR10+ and sIgM+ led us to hypothesize that RV IgM ASC can migrate to both chemokine receptor ligands CCL28 and CCL25. Of note, previous in vitro chemotaxis data (26) had shown that IgA ASC but not IgM or IgG ASC cells were responsive to CCL28. Due to the limited number of peripheral blood mononuclear cells that can be isolated from a RV-infected child, we tested this hypothesis in the mouse model.

Mesenteric lymph node cells were harvested from mice orally inoculated with murine RV (EC) 10 days postinfection, when the number of RV IgM ASC peak at this site (37) (data not shown). CCL25 and CCL28 responsiveness was tested in Transwell chemotaxis assays, and the migrated cells were analyzed by Elispot for total and RV-specific IgA and IgM ASC (Fig. 10). RV IgM ASC migrated efficiently to CCL28 (51.9% ± 3.4%) and to a lesser extent to CCL25 (28.3% ± 4.9%). As previously shown, RV IgA ASC responded to CCL25 (28.9% ± 0.04%) (4) and importantly also to CCL28 (50.3% ± 6.4%).

The magnitude of RV-specific IgA and IgM ASC migration to CCL25 and CCL28 was comparable to that of total IgA and IgM ASC in these mice. Interestingly, the total IgM ASC response to CCL28 from RV-infected mice was higher (26.9% ± 2.9%) than in noninfected mice (7.4% ± 1.24%) and to what has been reported previously (26) from noninfected mice. RV-specific IgM ASC also responded to CTACK/CCL27 (data not shown). From these experiments, we conclude that RV-specific IgM and IgA ASC migrate efficiently to CCL25 and CCL28 and that acute RV infection enhances the CCL28 responsiveness of total IgM B cells, presumably by upregulating CCR10 expression.

DISCUSSION

We have determined that during an acute RV infection in children, IgD− B cells that express RV-sIg have the phenotype of gut-homing plasma cells and plasmablasts (large lymphocytes that express: CD38high, CD27high, CD138+/−, CCR6−, α4β7+, CCR9+, CCR10+, CLA−, L-selectinint/−, and sIgM+, sIgG−, sIgA+/−). During the convalescent phase, the phenotype shifts and corresponds to that of memory B cells that do or do not have an intestinal homing phenotype (small and large lymphocytes CD38int/−, CD27int/−, CCR6+, α4β7+/−, CCR9+/−, and CCR10−). Furthermore, we have shown that a large percentage of sIgM+ B cells from acutely infected children coexpress CCR10 and that IgM ASC from infected mice migrate to the CCR10 ligand CCL28.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which extensive characterization and comparison of the phenotype of effector and memory antigen-specific B cells from children have been performed. Most studies that have addressed the phenotypes of antigen-specific ASC have relied on immunomagnetic isolation of cell subsets before their actual analysis by Elispot (18, 19, 25). Moreover, few phenotypic studies have been performed on antigen-specific human memory B cells (11, 27). Most of our knowledge regarding the phenotype of human ASC and memory B cells comes from the study of non-antigen-specific populations (16, 28, 31, 33). Most of these studies have been done with cells from healthy adults, adults with reactive plasmacytosis (16), allergic patients (15), and patients with autoimmunity (31). Nonetheless, the phenotype that we have described for RV ASC and memory B cells from RV-infected children is generally in agreement with these previous studies. Taking into account that preliminary results in adults acutely infected with and convalescent from RV diarrhea have shown that the maturation markers (CD38, CD27, CD138, and CCR6) on RV-specific B cells are similar to what we report here for children, our results suggest that these maturation markers are similarly regulated in children after primary and secondary infection and in adults after secondary infection.

The expression of CD27 was initially proposed as a marker of memory B cells (20). Memory CD27+ B cells include both IgD+ and IgD− subsets (34). Additional experiments will be required to determine if CD27+ IgD+ RV-sIg B cells have the same phenotype as the IgD− RV-sIg cells that we have characterized. Recent studies suggested that high expression of CD27 could be used to identify ASC (1, 31). In the experiments costaining both CD38 and CD27, we show that although all cells expressing high levels of CD38 also express high levels of CD27, the opposite is not true (Fig. 7). Moreover, the percentage of RV-sIg cells from acutely infected children that express CD38high is higher than the percentage of RV-sIg that express CD27high (Fig. 3b). Further experiments are needed to more precisely determine which of the two markers (CD38high or CD27high) is the best to identify RV ASC, but these findings suggest that for immune cells originating in the gastrointestinal tract, CD38 may be a more inclusive marker.

CCR6, the chemokine receptor for MIP-3α/CCL20, is expressed on naive and memory B cells but not on ASC (21). Although its role in B-cell homeostasis is unclear, our results confirm that its presence can be used to differentiate ASC from memory B cells following RV infection. Whether this finding holds true for memory cells elicited following parenteral immunization remains to be determined. CCR6 does not seem to be involved in tissue-specific trafficking of B cells because CCL20 is expressed widely in inflamed intestinal, skin, and lung tissue (23). The reason why mice deficient in CCR6 have impaired humoral immune responses to RV and other intestinal antigens is probably related not to impaired B-cell function but rather to the impairment of dendritic cell localization within Peyer's patches (9). Future studies focused on the CD4+ T-cell response of these mice will help clarify this issue.

The detection of CCR10 on RV-sIg cells and the fact that RV ASC can migrate to CTACK might indicate that they have the potential to home to the skin, where CTACK is expressed (7). However, tissue-specific homing to the skin requires the appropriate adhesion homing receptor-ligand pairs for interaction with cutaneous vessels (CLA, LFA-1, and α4β1). This does not seem to be the case for RV-sIg-expressing B cells because we have shown that these cells do not express CLA and more importantly that CCR10 and CLA are not coexpressed in the great majority of RV-sIg cells during acute infection. Thus, while the cells of interest express CCR10 and thus are responsive to their ligands, the expression of additional tissue-specific adhesion molecules (α4β7 but not CLA) directs RV-specific B cells to the intestine but not the skin. Our results support the hypothesis of a differential role of CCR10 in homing of intestinal ASC versus skin T cells. In the B-cell subset, CCR10 is coexpressed with α4β7, allowing tethering and rolling on the lamina propria intestinal venules, while on T cells, CCR10 is accompanied by CLA expression and absence of α4β7, limiting access to the intestinal endothelium (22).

Our flow cytometry results suggest that most of the RV-specific B cells expressing CCR9 and CCR10 are likely to be the same rather than distinct populations of ASC (Fig. 4, 5, and 7). These results are consistent with previous studies in mice (26) and humans (24) that show that there is a population of IgA ASC in the mesenteric lymph nodes that can respond to both CCL28 and CCL25. It is possible, however, that a fraction of the cells detected during acute infection in children express only CCR10 or CCR9. The expression of CCR9 on RV-specific B cells would play a critical role in the selective localization of the RV-specific immune response, since CCL25 is predominantly expressed by epithelial cells in the small intestine and is not expressed in the colon or other extraintestinal tissues where CCL28 is expressed (22). However, cells expressing only CCR10 have the potential to migrate to nonintestinal mucosal tissues (like the trachea, mammary gland, and salivary gland), where CCL28 is highly expressed. In addition, some of these CCR10+ cells could potentially migrate to bone marrow, where it has been recently shown that CCL28 is expressed and CCR10+ plasmablasts are found (30). In addition to CCR10, CXCR4 and SDF are likely to contribute to bone marrow localization (reviewed in reference 23). This is consistent with the observation that cells isolated from gut-associated lymphoid tissue can repopulate extraintestinal as well as intestinal sites (5). Given the recent finding that a period of systemic viremia is associated with acute RV infection (2), it might be advantageous to produce RV-immune cells with homing potential for sites other than the small bowel.

Since we have defined a phenotype of ASC in peripheral blood most likely targeted to the small intestine lamina propria, it will be of great interest to correlate the presence and quantity of these cells with the quantity and phenotype of RV-specific plasmablast or ASC present in intestine of both children and adults following RV infection. We predict that the great majority of RV-specific ASC residing in the small intestine lamina propria, and thus responsible for protection from reinfection, will be α4β7+ CCR10+ CCR9+. Future studies will be directed at determining if the quantity of either acute- or convalescent-phase gut-targeted B cells is a better correlate of protective immunity than levels of circulating or gut antibodies, as has been predicted previously (6, 12).

Although the trafficking profile of the great majority of cells detected during acute infection was that of gut-committed cells, surprisingly, this phenotype was less predominant in cells detected during convalescent phase, which were CCR6+ CD38int/−, mostly memory cells, and very few if any residual ASC. In this population of ASC, CCR10 was absent, as previously reported (24), and the expression of α4β7 and CCR9 was diminished (Fig. 5). The coexpression of α4β7 and CCR9 distinguished three different subsets of convalescent RV-sIg cells (Fig. 7). All CCR9+ cells coexpressed α4β7, and this subset of double positive cells is the most likely population that, upon restimulation, could efficiently generate new gut-targeted plasmablasts or ASC. The development of this population of B cells is very likely influenced by the intestinal Peyer's patch dendritic cells, as has been shown for T cells (17, 29) or by other factors in the intestinal milieu. The other two subpopulations (α4β7+ CCR9− and α4β7− CCR9−) are more likely to remain in the circulation or traffic elsewhere after restimulation, since they express the intestinal homing integrin but not the tissue-specific chemokine receptor. Since we show that most of the convalescent RV-sIg cells express CCR6, this receptor may play a role in the recruitment of these cells to diverse epithelial sites of inflammation. In addition, it would be of interest to study the expression of other chemokine receptors that allow recirculation through secondary lymphoid tissues, such as CCR7 and CXCR5 (23), on these cells.

The generation of nonintestinally committed memory B cells in children was suggested from our previous experiments, which showed that adults' RV-sIg B cells expressed more α4β7 than children′s B cells (14) and consistent with the recent evidence that an important fraction of children with RV infection appear to develop antigenemia (2). This result is also in agreement with our findings in the murine model of RV infection where, in parallel with the predominant mucosal IgA response (B cells localized to Peyer's patches and intestinal lamina propria), a systemic IgG and IgA response (B cells localized in spleen and bone marrow) develops (37).

We have shown that the total IgD− B-cell pool (non-antigen specific) in acutely infected children is significantly influenced by the acute RV infection (Fig. 3a, 5a, and 10). During acute infection, we see a significant increase in circulating B cells (non-RV specific) expressing the phenotype of gut-committed cells. This finding might be explained by a massive polyclonal activation of B cells (1) in the gut during RV infection that generates large numbers of activated non-RV-specific B cells. Recent results in the mouse model support this interpretation (3). This nonspecific activation of memory B cells would occur in the Peyer's patches or mesenteric lymph nodes, where the dendritic cells are able to establish specific homing features (17, 29) and where the local microenvironment is likely to have the signals (cytokines) involved in α4β7, CCR9, and CCR10 induction. These signals remain to be elucidated. It also remains to be determined whether the RV-induced nonspecific B-cell activation is unique to a RV infection or a more general phenomenon during any gut infection. The recent preliminary report that RV may activate B cells via TOLL-like receptor 4 could imply a more specific role for RV infection (S. E. Blutt, S. Crawford, K. L. Warfield, D. E. Lewis, M. K. Estes, and M. E. Conner, 8th International Symposium on Double Stranded RNA Viruses, Castelvecchio Pascoli, Italy, 2003).

Prior studies with Elispot (14) showed that during primary acute RV infection, the great majority of circulating ASC were IgM. This result is confirmed and extended in the present study with flow cytometry: a mean of 48.5% of the RV-sIg large IgD− B cells during acute infection express IgM on their surfaces (Fig. 8). Also in agreement with our previous studies, B cells from a subset of children expressed IgA (Fig. 8 and 9). Our finding of B cells with RV-sIg and the phenotype of ASC is in agreement with previous studies that showed that circulating B cells with intracellular Ig (ASC) also have sIg (15). Nonetheless, ASC have less sIg than B cells that do not have intracellular immunoglobulin (15). This latter finding probably explains why the mean intensity of fluorescence due to the GFP-VLPs on B cells with RV-sIg is lower on ASC than on memory B cells (Fig. 2). An alternative (but not mutually exclusive) explanation might be that the B-cell receptor on the cells detected during convalescence has a higher affinity for the GFP-VLPs. The low level of expression of sIg on ASC could also help to explain the fact that when one adds the percentages of B cells with RV-sIg that express IgA, IgG, and IgM, one only detects approximately 79% (Fig. 7) of the cells, suggesting that our isotype-specific reagents are not detecting all cells with RV-sIg. Since titration experiments have shown that we are with saturating concentrations of our isotype-specific antibodies, we believe the most likely explanation for this observation is that the GFP-VLPs (which have highly repetitive epitopes on their surfaces) are more sensitive in detecting RV-sIg than our isotype-specific reagents.

In the present study we show that RV-sIgM+ cells also express CCR10+. This result was unexpected, based on our previous studies (4, 24, 26) with cells from uninfected mice, where important chemotactic responses to CCL25 and CCL28 were seen only in IgA ASC, and IgM ASC failed to migrate to these chemokines and had very low levels of CCR10 expression. Our findings in children (Fig. 8 and 9) were supported by chemotactic studies with cells from mesenteric lymph nodes of RV-infected mice. In these experiments not only did the RV-specific IgM cells migrate efficiently to CCL28 and CCL25 but also the total IgM ASC population migrated to CCL28 (Fig. 10), implying that RV infection generally upregulates expression of CCR10 in total mucosal B cells. We do not think that the coexpression of IgM and CCR10 on RV- sIg cells is related specifically to the fact that our studies were performed with cells from children, since in a limited number of adults with RV infection we have also seen RV-sIg sIgM-expressing B cells that coexpress CCR10 (unpublished data). Current experiments are aimed at determining if the coexpression of CCR10 and sIgM is initiated by the specific viral antigen, mucosal priming, or the fact that the ASC that we have identified are recently activated antibody-secreting cells.

A major impediment to the development of RV vaccines is the lack of a marker that correlates with protection (12). From our other studies in the mouse model, it has been concluded that following oral immunization, RV-specific B cells must be localized to the intestinal epithelium to be protective (36). We thus hypothesize that a potentially useful correlate of protection will be the quantity of circulating acute and/or convalescence phase intestinally committed RV B cells. In this study we demonstrate the feasibility of identifying and quantifying circulating RV-specific effector and memory B cells targeted to the intestine in young children. This ability will provide investigators, for the first time, with new analytic approaches to assist in identifying critical determinants of protective immunity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, FIRCA grant TWO5647-02, NIH grants R01 AI21362-20 and AI47822, Specialized Centers of Research grant HL67674, and Digestive Disease Center grant DK56339.

We thank the subjects who participated in this study for their generosity and the personnel of the Pediatrics Department of San Ignacio Hospital for their help in identifying children with diarrhea.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernasconi, N. L., E. Traggiai, and A. Lanzavecchia. 2002. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science 298:2199-2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blutt, S. E., C. D. Kirkwood, V. Parreno, K. L. Warfield, M. Ciarlet, M. K. Estes, K. Bok, R. F. Bishop, and M. E. Conner. 2003. Rotavirus antigenaemia and viraemia: a common event? Lancet 362:1445-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blutt, S. E., K. L. Warfield, D. E. Lewis, and M. E. Conner. 2002. Early response to rotavirus infection involves massive B-cell activation. J. Immunol. 168:5716-5721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman, E. P., N. A. Kuklin, K. R. Youngman, N. H. Lazarus, E. J. Kunkel, J. Pan, H. B. Greenberg, and E. C. Butcher. 2002. The intestinal chemokine thymus-expressed chemokine (CCL25) attracts IgA antibody-secreting cells. J. Exp Med. 195:269-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandtzaeg, P., I. N. Farstad, and G. Haraldsen. 1999. Regional specialization in the mucosal immune system: primed cells do not always home along the same track. Immunol. Today 20:267-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, K. A., J. A. Kriss, C. A. Moser, W. J. Wenner, and P. A. Offit. 2000. Circulating rotavirus-specific antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) predict the presence of rotavirus-specific ASCs in the Human small intestinal lamina propria. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1039-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butcher, E. C., M. Williams, K. Youngman, L. Rott, and M. Briskin. 1999. Lymphocyte trafficking and regional immunity. Adv. Immunol. 72:209-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charpilienne, A., M. Nejmeddine, M. Berois, N. Parez, E. Neumann, E. Hewat, G. Trugnan, and J. Cohen. 2001. Individual rotavirus-like particles containing 120 molecules of fluorescent protein are visible in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29361-29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook, D. N., D. M. Prosser, R. Forster, J. Zhang, N. A. Kuklin, S. J. Abbondanzo, X. D. Niu, S. C. Chen, D. J. Manfra, M. T. Wiekowski, L. M. Sullivan, S. R. Smith, H. B. Greenberg, S. K. Narula, M. Lipp, and S. A. Lira. 2000. CCR6 mediates dendritic cell localization, lymphocyte homeostasis, and immune responses in mucosal tissue. Immunity 12:495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulson, B. S., K. Grimwood, I. L. Hudson, G. L. Barnes, and R. F. Bishop. 1992. Role of coproantibody in clinical protection of children during reinfection with rotavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1678-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crotty, S., P. Felgner, H. Davies, J. Glidewell, L. Villarreal, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Cutting edge: long-term B-cell memory in humans after smallpox vaccination. J. Immunol. 171:4969-4973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franco, M. A., and H. B. Greenberg. 2001. Challenges for Rotavirus vaccines. Virology 281:153-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franco, M. A., and H. B. Greenberg. 1999. Immunity to rotavirus infection in mice. J Infect. Dis. 179(Suppl. 3):S466-S469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez, A. M., M. C. Jaimes, I. Cajiao, O. L. Rojas, J. Cohen, P. Pothier, E. Kohli, E. C. Butcher, H. B. Greenberg, J. Angel, and M. A. Franco. 2003. Rotavirus-specific B cells induced by recent infection in adults and children predominantly express the intestinal homing receptor alpha4beta7. Virology 305:93-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horst, A., N. Hunzelmann, S. Arce, M. Herber, R. A. Manz, A. Radbruch, R. Nischt, J. Schmitz, and M. Assenmacher. 2002. Detection and characterization of plasma cells in peripheral blood: correlation of IgE+ plasma cell frequency with IgE serum titre. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 130:370-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jego, G., N. Robillard, D. Puthier, M. Amiot, F. Accard, D. Pineau, J. L. Harousseau, R. Bataille, and C. Pellat-Deceunynck. 1999. Reactive plasmacytoses are expansions of plasmablasts retaining the capacity to differentiate into plasma cells. Blood 94:701-712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson-Lindbom, B., M. Svensson, M. A. Wurbel, B. Malissen, G. Marquez, and W. Agace. 2003. Selective generation of gut tropic T cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT): requirement for GALT dendritic cells and adjuvant. J. Exp. Med. 198:963-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kantele, A., J. M. Kantele, E. Savilahti, M. Westerholm, H. Arvilommi, A. Lazarovits, E. C. Butcher, and P. H. Mäkela. 1997. Homing potentials of circulating lymphocytes in humans depend on the site of activation: oral, but not parenteral, typhoid vaccination induces circulating antibody-secreting cells that all bear homing receptors directing them to the gut. J. Immunol. 158:574-579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kantele, A., M. Westerholm, J. M. Kantele, P. H. Makela, and E. Savilahti. 1999. Homing potentials of circulating antibody-secreting cells after administration of oral or parenteral protein or polysaccharide vaccine in humans. Vaccine 17:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein, U., R. Kuppers, and K. Rajewsky. 1997. Evidence for a large compartment of IgM-expressing memory B cells in humans. Blood 89:1288-1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krzysiek, R., E. A. Lefevre, J. Bernard, A. Foussat, P. Galanaud, F. Louache, and Y. Richard. 2000. Regulation of CCR6 chemokine receptor expression and responsiveness to macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha/CCL20 in human B cells. Blood 96:2338-2345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunkel, E. J., and E. C. Butcher. 2002. Chemokines and the tissue-specific migration of lymphocytes. Immunity 16:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunkel, E. J., and E. C. Butcher. 2003. Plasma-cell homing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:822-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunkel, E. J., C. H. Kim, N. H. Lazarus, M. A. Vierra, D. Soler, E. P. Bowman, and E. C. Butcher. 2003. CCR10 expression is a common feature of circulating and mucosal epithelial tissue IgA antibody-secreting cells. J. Clin. Investig. 111:1001-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakew, M., I. Nordstrom, C. Czerkinsky, and M. Quiding-Jarbrink. 1997. Combined immunomagnetic cell sorting and Elispot assay for the phenotypic characterization of specific antibody-forming cells. J. Immunol. Methods 203:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazarus, N. H., E. J. Kunkel, B. Johnston, E. Wilson, K. R. Youngman, and E. C. Butcher. 2003. A common mucosal chemokine (mucosae-associated epithelial chemokine/CCL28) selectively attracts igA plasmablasts. J. Immunol. 170:3799-3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leyendeckers, H., M. Odendahl, A. Lohndorf, J. Irsch, M. Spangfort, S. Miltenyi, N. Hunzelmann, M. Assenmacher, A. Radbruch, and J. Schmitz. 1999. Correlation analysis between frequencies of circulating antigen-specific IgG-bearing memory B cells and serum titers of antigen-specific IgG. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:1406-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medina, F., C. Segundo, A. Campos-Caro, I. Gonzalez-Garcia, and J. A. Brieva. 2002. The heterogeneity shown by human plasma cells from tonsil, blood, and bone marrow reveals graded stages of increasing maturity, but local profiles of adhesion molecule expression. Blood 99:2154-2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mora, J. R., M. R. Bono, N. Manjunath, W. Weninger, L. L. Cavanagh, M. Rosemblatt, and U. H. Von Andrian. 2003. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer's patch dendritic cells. Nature 424:88-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakayama, T., K. Hieshima, D. Izawa, Y. Tatsumi, A. Kanamaru, and O. Yoshie. 2003. Cutting edge: profile of chemokine receptor expression on human plasma cells accounts for their efficient recruitment to target tissues. J. Immunol. 170:1136-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Odendahl, M., A. Jacobi, A. Hansen, E. Feist, F. Hiepe, G. R. Burmester, P. E. Lipsky, A. Radbruch, and T. Dorner. 2000. Disturbed peripheral B lymphocyte homeostasis in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 165:5970-5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parashar, U. D., E. G. Hummelman, J. S. Bresee, M. A. Miller, and R. I. Glass. 2003. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:565-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarte, K., F. Zhan, J. De Vos, B. Klein, and J. Shaughnessy Jr. 2003. Gene expression profiling of plasma cells and plasmablasts: toward a better understanding of the late stages of B-cell differentiation. Blood 102:592-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warnatz, K., A. Denz, R. Drager, M. Braun, C. Groth, G. Wolff-Vorbeck, H. Eibel, M. Schlesier, and H. H. Peter. 2002. Severe deficiency of switched memory B cells (CD27(+)IgM(-)IgD(-)) in subgroups of patients with common variable immunodeficiency: a new approach to classify a heterogeneous disease. Blood 99:1544-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weitkamp, J. H., N. Kallewaard, K. Kusuhara, D. Feigelstock, N. Feng, H. B. Greenberg, and J. E. Crowe, Jr. 2003. Generation of recombinant human monoclonal antibodies to rotavirus from single antigen-specific B cells selected with fluorescent virus-like particles. J. Immunol. Methods 275:223-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams, M. B., J. R. Rosé, L. S. Rott, M. A. Franco, H. B. Greenberg, and E. C. Butcher. 1998. The memory b cell subset that is responsible for the mucosal igA response and humoral immunity to rotavirus expresses the mucosal homing receptor, a4b7. J. Immunol. 161:4227-4235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Youngman, K. R., M. A. Franco, N. A. Kuklin, L. S. Rott, E. C. Butcher, and H. B. Greenberg. 2002. Correlation of tissue distribution, developmental phenotype, and intestinal homing receptor expression of antigen-specific B cells during the murine anti-rotavirus immune response. J. Immunol. 168:2173-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan, L., L. A. Ward, B. I. Rosen, T. L. To, and L. J. Saif. 1996. Systematic and intestinal antibody-secreting cell responses and correlates of protective immunity to human rotavirus in a gnotobiotic pig model of disease. J. Virol. 70:3075-3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zabel, B. A., W. W. Agace, J. J. Campbell, H. M. Heath, D. Parent, A. I. Roberts, E. C. Ebert, N. Kassam, S. Qin, M. Zovko, G. J. LaRosa, L. L. Yang, D. Soler, E. C. Butcher, P. D. Ponath, C. M. Parker, and D. P. Andrew. 1999. Hum. G protein-coupled receptor GPR-9-6/CC chemokine receptor 9 is selectively expressed on intestinal homing T lymphocytes, mucosal lymphocytes, and thymocytes and is required for thymus-expressed chemokine-mediated chemotaxis. J. Exp. Med. 190:1241-1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]