Abstract

We report that human T cells persistently infected with primate foamy virus type 1 (PFV-1) display an increased capacity to bind human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), resulting in increased cell permissiveness to HIV-1 infection and enhanced cell-to-cell virus transmission. This phenomenon is independent of HIV-1 receptor, CD4, and it is not related to PFV-1 Bet protein expression. Increased virus attachment is specifically inhibited by heparin, indicating that it should be mediated by interactions with heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans expressed on the target cells. Given that both viruses infect similar animal species, the issue of whether coinfection with primate foamy viruses interferes with the natural course of lentivirus infections in nonhuman primates should be considered.

Virus replication can be modulated by the presence of either homologous defective viral genomes or viruses of distinct classes capable of interfering with particular stages of the virus cycle in dually infected organisms. It is established that coinfection with other retroviruses (human T-cell leukemia virus types 1 and 2) (31), human herpesviruses (human herpesvirus type 6 [HHV-6], HHV-7, and HHV-8) (4, 7, 9, 12, 32), or nonpathogenic flavivirus GB virus (30) influences progression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) disease. Foamy viruses (FVs) are innocuous complex retroviruses that establish lifelong persistent infection in their hosts without inducing disease (13, 15, 17, 19). Persistence of primate foamy virus type 1 (PFV-1), the prototype of FVs, is associated with accumulation of a defective homologous provirus, PFVΔTas, generated by alternative splicing of the wild-type genomic RNA, deleting a 301-bp intron in the viral transactivator tas gene (18, 26, 33), which negatively interferes with replication of its parental counterpart by production of the regulatory Bet protein (18, 26, 33). Interestingly, FV distribution among mammalian species mirrors that of lentiviruses (15, 17), and although FVs display broad cell tropism, both infect T cells and macrophages (29).

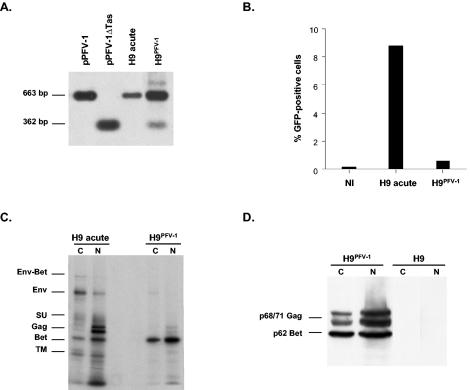

Looking for possible interference with lentivirus replication, we investigated the impact of acute PFV-1 infection on HIV-1 replication by exposing human H9 T cells (22) to X4 HIV-1LAI plus or minus PFV-1. No significant effect of PFV-1 infection on HIV-1 replication was noted as monitored by sequential p24 (CoulterR HIV-1 p24 antigen assay) and HIV-1 DNA quantification. However, due to massive cell lysis, the experiment could not be prolonged beyond 8 days postinfection (p.i.) (data not shown). We next examined this point in a system that harbors the PFV genome without cell lysis. Hence, H9 cells were initially infected with PFV-1 (0.1 PFU/ml), and cells that survived acute infection were cultured until disappearance of the cytopathic effect, which occurred after 4 weeks. At that time, remaining lysis-resistant H9 cells (referred to as H9PFV-1 cells hereafter) harbored the PFVΔTas genome, representing a minor fraction of the viral genomes, as reported with other human hematopoietic cell lines (Fig. 1A) (33). Persistent PFV-1 infection was confirmed by showing that H9PFV-1 cell virus production was reduced by >90%, as measured using BHK21 indicator cells expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of PFV-1 long terminal repeats (LTR) (28) (Fig. 1B). Accordingly, radio-immunoprecipitation of PFV-1 proteins from both the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of H9PFV-1 cells showed that they mainly produced the Bet protein (11) (Fig. 1C). Because nuclear PFV-1 Gag doublets were also faintly detected in H9PFV-1 cells, both fractions were analyzed by Western blotting, which allows more accurate detection of this product (Fig. 1D): indeed, H9PFV-1 cells still expressed PFV-1 Gag, indicating that they retained the capacity to drive protein expression from the 5′ LTR.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of H9 cells persistently infected with PFV-1 (H9PFV-1). (A) Southern blot analysis: DNA from H9PFV-1 cells, acutely infected H9 parental cells, and pPFV-1 or the defective form of the provirus (pPFV-1ΔTas), was digested by EcoRI and NcoI, separated in a 0.8% agarose gel, and blotted onto nitrocellulose before hybridization with a radiolabeled EcoRI-NcoI pSVTas 663-bp probe (14). (B) Assessment of PFV-1 production by H9PFV-1 cells: BHK21 cells, which express GFP under the control of PFV-1 LTR, were cultured for 48 h with culture supernatants from H9PFV-1, acutely infected or uninfected (NI) control H9 cells, before FACS analysis for GFP expression. (C) Radio-immunoprecipitation of PFV-1 proteins: proteins from both nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) fractions of H9PFV-1 or acutely infected H9 parental cells were immunoprecipitated with a PFV-1-specific rabbit antiserum, as reported previously (11). (D) Western blot analysis of H9PFV-1 and parental cells: nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extracts were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilin-P; Millipore) before detection of PFV-1 proteins by the PFV-1 rabbit antiserum.

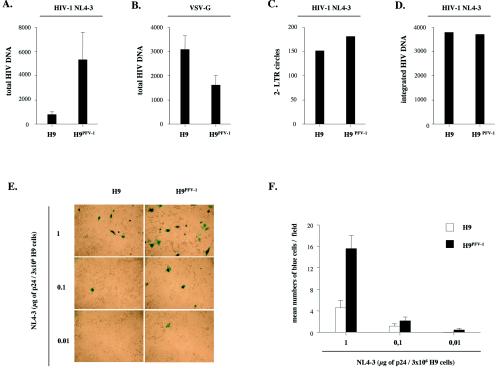

To investigate the impact of persistent infection by PFV-1 on the early steps of the HIV-1 replication cycle, we examined HIV-1 entry, nuclear import, and integration in H9PFV-1 cells. The H9PFV-1 cells were synchronized in G1 by double-thymidin block (2 mM; Sigma-Aldrich) (6) before a 2-h exposure to X4 HIV-1NL4-3 (1 μg of p24 equivalent/3 × 106 cells; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagents Program). Virus-exposed cells were kept arrested for 24 h at the G1/S boundary with 5 μg of aphidicolin (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml to preserve nuclear envelope integrity and maintained in the presence of the HIV protease inhibitor Saquinavir (1 μg/ml; Roche Pharmaceuticals) to limit analysis to single-round infection. HIV-1 DNA copy numbers detected 6 h p.i. averaged 830 ± 214 and 5,341 ± 2,229 (mean ± SEM; n = 4) per 103 parental and H9PFV-1 cells (sixfold increase), respectively (Fig. 2A). Specificity of this phenomenon was controlled by exposing H9PFV-1 cells to a vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped NL4-3 virus. Strikingly, PCR analysis 6 h p.i. showed that HIV-1 DNA amounts were 50% lower in H9PFV-1 cells than in parental cells, indicating that the former had a reduced capacity to support virus entry via endocytosis (Fig. 2B). There was no difference between parental and H9PFV-1 cells concerning HIV-1 reverse transcription (reverse transcription efficiency, ≥80%), nuclear import, and integration (Fig. 2C and D), indicating that persistent infection by PFV-1 led to increased permissiveness to HIV-1 without affecting major postentry events.

FIG. 2.

Persistent PFV-1 infection of H9 cells increases permissiveness to HIV-1 and promotes cell-to-cell virus transmission. H9PFV-1 and parental cells were exposed at 25°C via spinoculation (1,200 × g) to (A, C, and D) HIV-1NL4-3 or (B) a VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1NL4-3 virus (1 μg of p24 equivalent/3 × 106 cells). (A and B) Virus entry was assessed 6 h p.i. by real-time LTR U3-U5 PCR performed with 5′-CTAACTAGGGAACCCACG (nt 498 to 516) sense and 5′-CTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACAC (AA55; nucleotides 616 to 635) antisense primers; results were normalized relative to 103 cells and are shown as means plus SEM (n = 4). (C) HIV-1 nuclear import was assessed 24 h p.i. by real-time 2-LTR circle PCR using 5′-GGAACCCACTGCTTAAGCC (nucleotides 506 to 524) sense and 5′-TGTGTAGTTCTGCCAATCAGG (nucleotides 75 to 95) antisense primers with subsequent detection of the corresponding amplicons by hybridization probes. Standard curves (range, 2 to 2 × 107 copies) were generated with the 2-LTRA plasmid, which contains the 2-LTR U3-U5 junction. Results are normalized relative to 104 copies of full-length HIV-1 DNA detected by LTR U3-gag PCR. (D) HIV-1 integration was assessed 24 h p.i. by real-time Alu-LTR nested PCR, essentially as described previously (5). Primers sense L-M667 (5′-ATGCCACGTAAGCGAAACTCTGGCTAACTAGGGAACCCACTG), antisense Alu-1 (5′-TCCCAGCTACTGGGGAGGCTGAGG), and sense Alu-2 (5′-GCCTCCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTACAG) were used for the first 12 amplification cycles. Primers sense Lambda-T (5′-ATGCCACGTAAGCGAAACT) and antisense AASSM (5′-GCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGACTAA, nucleotides 609 to 633) were used for the second-round PCR. Detection of the corresponding amplicons was achieved with hybridization probes, and standard curves for integrated viral DNA were generated by using HeLa cells infected with a Δenv HIV-1 R7 Neo virus. Integrated proviral DNA copy numbers were normalized relative to 104 copies of full-length HIV-1 DNA. (E and F) Cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1 by H9PFV-1 cells: H9PFV-1 and parental cells were spinoculated at 4°C for 2 h in the presence of HIV-1NL4-3 (0.01 to 1 μg of p24 equivalent/3 × 106 cells) before they were added for 24 h to P4-CCR5 indicator cells that express the β-galactosidase reporter gene under the control of HIV-1 LTR (23). P4-CCR5 cells were fixed and processed for 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside staining 48 h later (E). Results are expressed as mean numbers (plus SEM) of blue cells per field (F); 30 fields were counted for each condition; they are representative of one experiment out of two.

To examine whether persistent infection by PFV-1 also enhanced HIV-1 cell-to-cell transmission, H9PFV-1 cells were exposed to HIV-1NL4-3 and cocultured for 24 h with P4-CCR5 indicator cells expressing the β-galactosidase gene under HIV-1 LTR control (1). Virus transmission was then two- to sixfold more efficient with H9PFV-1 cells than with parental cells (Fig. 2E and F). Because these data suggested that persistent PFV-1 infection enhanced membrane attachment of HIV-1, we next assessed H9PFV-1 cell-associated p24 two h after exposure to HIV-1NL4-3. Cell-associated p24 averaged 480 ± 302 ng/106 H9PFV-1 cells versus 45 ± 20 ng/106 H9PFV-1 cells for parental cells (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 4; 10-fold increase). Spinoculation, which increased the level of cell-associated p24 by 10- to 50-fold relative to simple incubation, did not change the overall pattern, ruling out the effect of centrifugation on virus attachment to H9PFV-1 cells (Fig. 3A and B). H9PFV-1 cell capacity to bind X4 HIV-1NLHX (gift of M. Bukrinsky, Picower Institute of Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y.), R5 HIV-1NLAD8 (gift of P. Charneau, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), SIVmac251 (gift of R. Legrand, CEA, Fontenay aux Roses, France), or the VSV-G pseudotype was then tested (Fig. 3C). H9PFV-1 cells displayed 5- to 14-fold-increased capacity to bind the HIV-1 or simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) strains tested. No difference was noted regarding VSV-G pseudotype binding, which emphasizes the specificity of the phenomenon.

FIG. 3.

Increased capacity of H9PFV-1 cells to capture HIV-1 virions. (A, B) Determination of p24 associated with H9PFV-1 or with parental cells exposed to HIV-1NL4-3: cells were (A) spinoculated or (B) simply incubated for 2 h at 4°C in the presence of the virus (1 μg of p24 equivalent/3 × 106 cells) and washed three times to remove unbound virus, and p24 in cell lysates was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; data are from a representative experiment. (C) Binding to H9PFV-1 cells of different HIV-1 strains, SIVmac and VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1NL4-3: H9PFV-1 and parental cells were exposed to viruses, as above, before being processed for p24 (HIV) or p27 (SIV; Coulter SIV core antigen assay) dosage; results are expressed as fold increases of H9PFV-1 cell over parental cell-associated p24 and are representative of one experiment out of two.

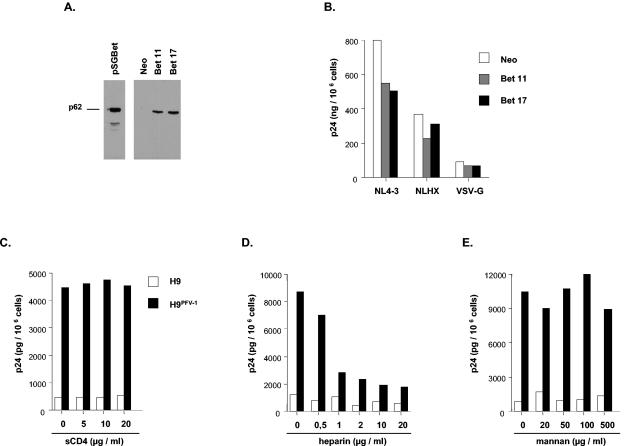

Whether Bet was responsible for increased attachment of HIV-1 to H9PFV-1 cells was then examined, because Bet plays an important role in the establishment and/or maintenance of PFV-1 persistence (16, 25). For that purpose, a murine leukemia virus (MLV)-based retrovirus vector (MSCV retroviral expression system; Clontech) was used to stably transduce Bet into H9 cells (Fig. 4A). After exposure to HIV-1NL4-3 of two clones selected for high levels of Bet expression, no difference was noted regarding virus binding, entry, or replication (Fig. 4B and data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Bet-independent attachment of HIV-1 to H9PFV-1 cells is mediated by heparan sulfates. (A and B) Characterization of clones Bet 11 and Bet 17. (A) Western-blot analysis of H9 clones, transduced with Bet-expressing (Bet 11 and Bet 17) or empty (Neo) MLV-based retroviral vectors, was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1D; the pSGBet expression vector has been previously described (16). (B) Assessment of HIV-1 binding on Bet-expressing cells. Clones Bet 11 and Bet 17 and a control clone transduced with the Neo empty vector were exposed to HIV-1NL4-3, HIV-1NLHX, or the VSV-pseudotyped HIV-1NL4-3 virus and processed as described above (see the legend for Fig. 3A). (C to E) Inhibition of HIV-1 attachment to H9PFV-1 cells by soluble CD4 (sCD4) or glycans: (C) virus supernatant was preincubated for 1 h with sCD4 before being added to cells; alternatively, cells were incubated for 1 h with (D) heparin or (E) mannan, prior to virus exposure; p24 dosage was performed as described above (see the legend for Fig. 3A). Results are representative of one experiment out of two.

We finally examined the receptors involved in attachment of HIV-1 to H9PFV-1 cells. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis did not disclose any difference with parental cells regarding CD4, CXCR4, CCR5, or type C lectin DC-SIGN/CD209 expression (10) (data not shown). In addition, preincubating virus with soluble CD4 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagents Program) did not affect binding of HIV-1NL4-3 to H9PFV-1 cells (Fig. 4C). Because surface polyanions and glycans also contribute to HIV-1 attachment to target cells (20, 21, 27), the effect of heparin, mannan, and dextran 10000 (all from Sigma-Aldrich) on binding of HIV-1NL4-3 to cells was assessed: 1-h preincubation of H9PFV-1 cells with heparin inhibited HIV-1-enhanced cell association in a dose-dependent manner, while neither mannan nor dextran had such an effect (Fig. 4D and E and data not shown). Thus, change of surface expression of heparan-sulfate proteoglycans could be responsible for increased capacity of H9PFV-1 cells to bind HIV-1 (2).

These results demonstrate that H9 cells persistently infected with PFV-1 display an increased capacity to capture HIV-1 via interactions with heparan-sulfate proteoglycans, whose ability to attach HIV-1 gp120 is well documented (24). The phenomenon is independent of PFV-1 Bet, suggesting that other viral proteins modulate expression of membrane proteoglycans. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of PFV-1 LTR complete silencing in H9PFV-1 cells. Although our findings cannot be extrapolated to in vivo-coinfected nonhuman primates, they nonetheless provide the first evidence of interactions between FVs and lentiviruses. Because PFVs replicate in mucosae of infected individuals (3, 8) and can be isolated from blood T cells (29), one should consider the hypothesis that PVF-infected cells may be involved in the natural history of SIV infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche contre le SIDA, by SIDACTION-Ensemble Contre le SIDA, and by the Association de Recherche sur les Deficits Immunitaires Viro-Induits (Paris, France).

We gratefully thank Micael Bukrinsky for the gift of the pNLHX HIV-1 strain; Robert Siliciano for the gift of pNL4-3 GFP reporter virus; Roger Legrand and Bruno Vaslin for the gift of SIVmac251 and critical discussions; and the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagents Program for the gift of the pNL4-3 molecular clone and the pVSV-G expression vector.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakri, Y., C. Schiffer, V. Zennou, P. Charneau, E. Kahn, A. Benjouad, J. C. Gluckman, and B. Canque. 2001. The maturation of dendritic cells results in postintegration inhibition of HIV-1 replication. J. Immunol. 166:3780-3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernfield, M., M. Gotte, P. W. Park, O. Reizes, M. L. Fitzgerald, J. Lincecum, and M. Zako. 1999. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:729-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blewett, E. L., D. H. Black, N. W. Lerche, G. White, and R. Eberle. 2000. Simian foamy virus infections in a baboon breeding colony. Virology 278:183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonura, F., A. M. Perna, F. Vitale, M. R. Villafrate, E. Viviano, R. Guttadauro, G. Mazzola, and N. Romano. 1999. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) by variant B of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6). New Microbiol. 22:161-171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brussel, A., and P. Sonigo. 2003. Analysis of early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA synthesis by use of a new sensitive assay for quantifying integrated provirus. J. Virol. 77:10119-10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhary, N., and J. C. Courvalin. 1993. Stepwise reassembly of the nuclear envelope at the end of mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 122:295-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emery, V. C., M. C. Atkins, E. F. Bowen, D. A. Clark, M. A. Johnson, I. M. Kidd, J. E. McLaughlin, A. N. Phillips, P. M. Strappe, and P. D. Griffiths. 1999. Interactions between beta-herpesviruses and human immunodeficiency virus in vivo: evidence for increased human immunodeficiency viral load in the presence of human herpesvirus 6. J. Med. Virol. 57:278-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falcone, V., J. Leupold, J. Clotten, E. Urbanyi, O. Herchenroder, W. Spatz, B. Volk, N. Bohm, A. Toniolo, D. Neumann-Haefelin, and M. Schweizer. 1999. Sites of simian foamy virus persistence in naturally infected African green monkeys: latent provirus is ubiquitous, whereas viral replication is restricted to the oral mucosa. Virology 257:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fantry, L. E., and F. R. Cleghorn. 1999. HHV-6 infection in patients with HIV-1 infection and disease. AIDS Read 9:198-203, 221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geijtenbeek, T. B., D. S. Kwon, R. Torensma, S. J. van Vliet, G. C. van Duijnhoven, J. Middel, I. L. Cornelissen, H. S. Nottet, V. N. KewalRamani, D. R. Littman, C. G. Figdor, and Y. van Kooyk. 2000. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell 100:587-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giron, M. L., H. de The, and A. Saib. 1998. An evolutionarily conserved splice generates a secreted env-Bet fusion protein during human foamy virus infection. J. Virol. 72:4906-4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrington, W., Jr., L. Sieczkowski, C. Sosa, S. Chan-a-Sue, J. P. Cai, L. Cabral, and C. Wood. 1997. Activation of HHV-8 by HIV-1 tat. Lancet 349:774-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heneine, W., W. M. Switzer, P. Sandstrom, J. Brown, S. Vedapuri, C. A. Schable, A. S. Khan, N. W. Lerche, M. Schweizer, D. Neumann-Haefelin, L. E. Chapman, and T. M. Folks. 1998. Identification of a human population infected with simian foamy viruses. Nat. Med. 4:403-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lecellier, C. H., M. Neves, M. L. Giron, J. Tobaly-Tapiero, and A. Saib. 2002. Further characterization of equine foamy virus reveals unusual features among the foamy viruses. J. Virol. 76:7220-7227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lecellier, C. H., and A. Saib. 2000. Foamy viruses: between retroviruses and pararetroviruses. Virology 271:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lecellier, C. H., W. Vermeulen, F. Bachelerie, M. L. Giron, and A. Saib. 2002. Intra- and intercellular trafficking of the foamy virus auxiliary Bet protein. J. Virol. 76:3388-3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linial, M. L. 1999. Foamy viruses are unconventional retroviruses. J. Virol. 73:1747-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meiering, C. D., K. E. Comstock, and M. L. Linial. 2000. Multiple integrations of human foamy virus in persistently infected human erythroleukemia cells. J. Virol. 74:1718-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meiering, C. D., C. Rubio, C. May, and M. L. Linial. 2001. Cell-type-specific regulation of the two foamy virus promoters. J. Virol. 75:6547-6557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mondor, I., S. Ugolini, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 attachment to HeLa CD4 cells is CD4 independent and gp120 dependent and requires cell surface heparans. J. Virol. 72:3623-3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel, M., M. Yanagishita, G. Roderiquez, D. C. Bou-Habib, T. Oravecz, V. C. Hascall, and M. A. Norcross. 1993. Cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediates HIV-1 infection of T-cell lines. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 9:167-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popovic, M., M. G. Sarngadharan, E. Read, and R. C. Gallo. 1984. Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science 224:497-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocancourt, D., C. Bonnerot, H. Jouin, M. Emerman, and J. F. Nicolas. 1990. Activation of a beta-galactosidase recombinant provirus: application to titration of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HIV-infected cells. J. Virol. 64:2660-2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roderiquez, G., T. Oravecz, M. Yanagishita, D. C. Bou-Habib, H. Mostowski, and M. A. Norcross. 1995. Mediation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 binding by interaction of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans with the V3 region of envelope gp120-gp41. J. Virol. 69:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saib, A., M. H. Koken, P. van der Spek, J. Peries, and H. de The. 1995. Involvement of a spliced and defective human foamy virus in the establishment of chronic infection. J. Virol. 69:5261-5268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saib, A., J. Peries, and H. de The. 1993. A defective human foamy provirus generated by pregenome splicing. EMBO J. 12:4439-4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seddiki, N., L. Rabehi, A. Benjouad, L. Saffar, F. Ferriere, J. C. Gluckman, and L. Gattegno. 1997. Effect of mannosylated derivatives on HIV-1 infection of macrophages and lymphocytes. Glycobiology 7:1229-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobaly-Tapiero, J., P. Bittoun, M. L. Giron, M. Neves, M. Koken, A. Saib, and H. de The. 2001. Human foamy virus capsid formation requires an interaction domain in the N terminus of Gag. J. Virol. 75:4367-4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Laer, D., D. Neumann-Haefelin, J. L. Heeney, and M. Schweizer. 1996. Lymphocytes are the major reservoir for foamy viruses in peripheral blood. Virology 221:240-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams, C. F., D. Klinzman, T. E. Yamashita, J. Xiang, P. M. Polgreen, C. Rinaldo, C. Liu, J. Phair, J. B. Margolick, D. Zdunek, G. Hess, and J. T. Stapleton. 2004. Persistent GB virus C infection and survival in HIV-infected men. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:981-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willy, R. J., C. M. Salas, G. E. Macalino, and J. D. Rich. 1999. Long-term non-progression of HIV-1 in a patient coinfected with HTLV-II. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 35:269-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasukawa, M., A. Hasegawa, I. Sakai, H. Ohminami, J. Arai, S. Kaneko, Y. Yakushijin, K. Maeyama, H. Nakashima, R. Arakaki, and S. Fujita. 1999. Down-regulation of CXCR4 by human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) and HHV-7. J. Immunol. 162:5417-5422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu, S. F., J. Stone, and M. L. Linial. 1996. Productive persistent infection of hematopoietic cells by human foamy virus. J. Virol. 70:1250-1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]