Abstract

The Thogoto virus ML protein suppresses interferon synthesis in infected cells. Nevertheless, a virus mutant lacking ML remained highly pathogenic in standard laboratory mice. It was strongly attenuated, however, in mice carrying the interferon-responsive Mx1 gene found in wild mice, demonstrating that enhanced interferon synthesis is protective only if appropriate antiviral effector molecules are present. Our study shows that the virulence-enhancing effects of some viral interferon antagonists may escape detection in conventional animal models.

Thogoto virus (THOV) is a tick-transmitted orthomyxovirus with a genome consisting of six negative-strand RNA segments. The sixth segment codes for the matrix protein M and the nonessential ML protein (7). ML represents a C-terminally elongated version of M that is translated from unspliced transcripts of segment 6. The extra 38 C-terminal amino acids lack decisive sequence motifs which would give clues regarding the function of the 34-kDa ML protein. Expression of ML rendered human 293 cells resistant to double-stranded-RNA-mediated activation of beta interferon (IFN-β) promoter constructs (7). Furthermore, unlike wild-type THOV, virus mutants lacking ML strongly induced IFN synthesis in infected cells but showed no obvious growth deficits in cell culture (7). Although these results suggested that ML may block innate immune responses in infected hosts, experimental proof of this concept was lacking.

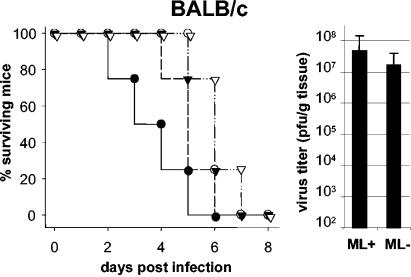

To address this question we infected groups of adult BALB/c mice with either 1 or 100 PFU of wild-type (ML-positive) or mutant (ML-negative) THOV by the intraperitoneal route. Both of these viruses were generated entirely from plasmids in a reverse-genetics system (17). The ML-negative strain of THOV differs by the insertion of one single nucleotide in RNA segment 6, which leads to a frameshift that prevents ML protein synthesis (7). Except for the absence of the ML gene product, the mutant virus showed a normal viral gene expression profile (7). All animals infected with either the ML-positive or the ML-negative THOV variant developed signs of severe disease within 3 to 6 days postinfection. Symptoms included hunched posture, ruffled fur, apathetic behavior, and weight loss. If weight loss exceeded 20%, the animals were sacrificed for ethical reasons. Disease development was slightly but not significantly delayed in animals infected with ML-negative THOV (Fig. 1, left). Livers of mice sacrificed at a late stage of disease contained very high titers of infectious THOV (Fig. 1, right). Titers of mutant virus were on average only about threefold lower than titers of wild-type THOV, indicating that mutant THOV lacking ML was not or at best marginally attenuated in BALB/c mice.

FIG. 1.

THOVs with or without ML protein are similarly pathogenic for Mx1-negative BALB/c mice. Groups of four to eight adult animals were infected by intraperitoneal injection of either wild-type THOV (ML+; solid symbols) or mutant virus (ML−; open symbols). Infection experiments with high virus dose (100 PFU; circles) or low virus dose (1 PFU; inverted triangles) yielded similar results. Mice were euthanized when disease symptoms became severe. (Left) Kinetics of disease development; (right) mean virus titers and standard deviations in livers of euthanized animals.

To explain this unexpected result, we considered two alternative explanations. First, although ML efficiently blocks IFN synthesis in cell culture, its in vivo role might be different. Second, the BALB/c mouse model might not be suitable for experiments of this kind. We favored the second possibility because most inbred mouse strains including BALB/c lack a functional IFN-regulated Mx1 gene and are highly susceptible to infections with orthomyxoviruses (16), in particular THOV (9). A large body of data from cell culture and experimental animal work indicates that Mx proteins are the principal mediators of IFN-dependent protection against infection with THOV (3, 9, 12, 15).

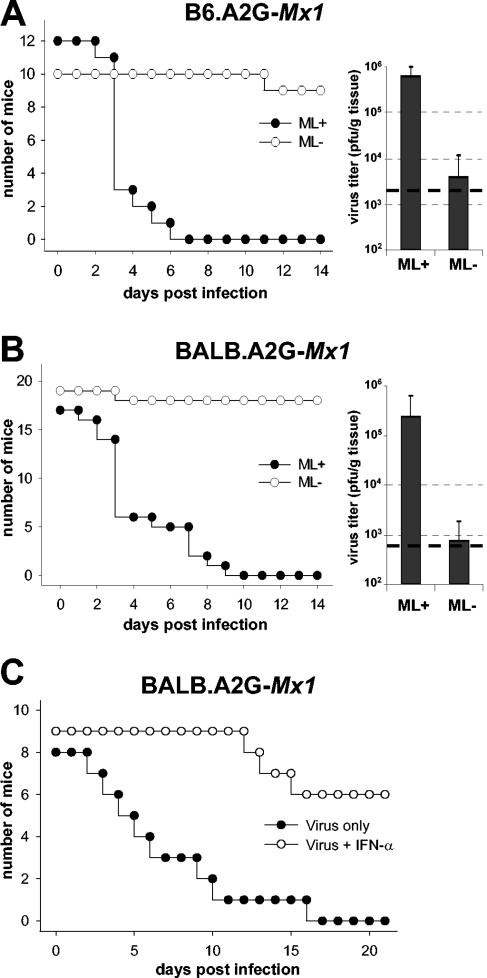

Pilot experiments with adult mice possessing a functional Mx1 gene (16) were not revealing because these Mx1-positive mice did not show any signs of disease or weight loss irrespective of whether large doses of ML-positive or ML-negative THOV were used for infection (data not shown). We argued that newborn mice might be more suitable for detecting biological differences between the two viruses. IFN responses are generally weak in embryonic tissue (10) and in newborns (13). Accordingly, the Mx1 resistance phenotype is not fully established in newborn animals but matures after birth and can be experimentally induced by administrating exogenous mouse IFN (8). We therefore determined whether wild-type THOV might be pathogenic for Mx1-positive newborns and whether the ML protein would enhance viral virulence under these conditions. In a first experiment we used B6.A2G-Mx1 mice, which are congenic to C57BL/6 mice but carry the functional Mx1 allele derived from strain A2G (11). Pups were infected within the first 24 h of life by intraperitoneal inoculation of 1,000 PFU of THOV. Wild-type THOV killed all 12 infected pups within 3 to 7 days. By contrast, mutant THOV lacking ML had no deleterious effect under these conditions (Fig. 2A, left). All except 1 of the 11 animals infected with ML-negative THOV remained healthy and developed normally during the complete observation period of 21 days. A similar result was obtained when BALB.A2G-Mx1 (Mx1-positive BALB/c-congenic) mice were used for infection studies (Fig. 2B, left). All 17 pups infected with wild-type THOV died within 10 days, whereas 18 of 19 pups infected with mutant THOV lacking ML survived. Survival times of pups infected with wild-type THOV differed considerably among litters, although individual animals of the same litter showed little variation (data not shown). As previously shown for influenza virus resistance in A2G mice (8), the resistance of Mx1-positive mice to THOV developed quickly after birth. If infected with wild-type THOV at an age of 3 days, all B6.A2G-Mx1 mice died within 9 days. Three-day-old pups of strain BALB.A2G-Mx1 were slightly more resistant: 50% of the animals survived under these conditions. If infected at an age of 5 days or older, all pups of both mouse strains resisted infection with wild-type THOV (data not shown). From cell culture experiments it is known that the IFN-dependent Mx defense system is extremely potent against THOV (9). Our data with adult and juvenile mice indicate that the Mx1 protein is also very efficient in vivo. Complete protection of these mice indicates that even the small amounts of IFN produced in response to infection with wild-type THOV can activate the Mx system sufficiently well.

FIG. 2.

THOV lacking ML is highly attenuated in Mx1-positive mice. (Left) Survival curves; (right) mean viral titers and standard deviations in the liver at 48 h after infection with wild-type or ML-negative THOV. Dashed lines (right), detection limits of the assays. (A) Groups of newborn B6.A2G-Mx1 mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection of 1,000 PFU of either wild-type (ML+) or mutant (ML−) THOV. (B) Groups of newborn BALB.A2G-Mx1 mice were infected by intraperitoneal injection of 1,000 PFU of either wild-type or mutant THOV. (C) Groups of newborn BALB.A2G-Mx1 mice were infected with 1,000 PFU of wild-type THOV in either plain medium or medium containing 10,000 U of human IFN-αB/D (which is active in mice).

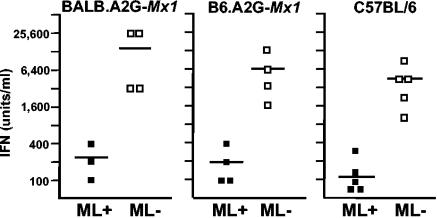

Groups of neonatally infected pups were sacrificed at 48 h postinfection for virus titration and serum IFN determination. B6.A2G-Mx1 mice infected with wild-type THOV contained on average about 6 × 105 PFU of virus per g of liver tissue, whereas the viral load in livers of littermates infected with the ML-negative mutant virus was about 100-fold lower (Fig. 2A, right). Similarly, BALB.A2G-Mx1 mice infected with wild-type THOV had more than 100-fold-higher titers of infectious virus in the liver than littermates infected with the ML-negative mutant virus (Fig. 2B, right). Serum IFN titers at 48 h postinfection were determined by an antiviral assay that measures cytokine-induced inhibition of infection of mouse L929 cells by a variant of vesicular stomatitis virus expressing green fluorescent protein (1). Serum of B6.A2G-Mx1 and BALB.A2G-Mx1 pups infected with the ML-negative mutant virus, on average, contained between 6,400 and 12,800 U of IFN per ml, respectively, which was at least 30 times more than in serum of pups harboring wild-type THOV (Fig. 3, left and middle). Similar results were obtained when serum IFN levels in infected Mx1-negative adult C57BL/6 mice were measured. At 24 h after infection with THOV lacking ML, serum IFN levels were about 4,000 U per ml on average. In contrast, average IFN titers in animals infected with wild-type THOV were only about 100 U per ml (Fig. 3, right). These data indicate that THOV lacking ML induces significantly higher levels of IFN than wild-type THOV early after infection, which obviously results in effective inhibition of viral replication in the liver and other organs of Mx1-positive mice. However, in the absence of a functional Mx system, the lifesaving potential of early IFN synthesis does not translate into a protective antiviral state.

FIG. 3.

Enhanced levels of IFN in serum of mice infected with THOV lacking ML. Groups of newborn Mx1-positive (left and middle) and adult Mx1-negative (right) mice were infected with 1,000 PFU of either wild-type (ML+) or ML-negative (ML−) THOV by the intraperitoneal route. Infected Mx1-positive animals were sacrificed at 48 h postinfection. Infected Mx1-negative animals (which develop disease very quickly [Fig. 1]) were sacrificed at 24 h postinfection. Serum IFN titers were determined by an antiviral assay.

If this view is correct, it should be possible to save Mx1-positive pups from the deleterious effects of wild-type THOV infection by supplying them with exogenous IFN. To test this hypothesis, we used newborn pups of strain BALB.A2G-Mx1 that we infected with 1,000 PFU of wild-type THOV suspended in either plain medium or medium containing 10,000 U of human IFN-αB/D (which is highly active in mouse cells [4]). Seven of the eight pups that received virus alone were dead by day 11 postinfection, and the remaining animal died on day 17 (Fig. 2C). In contrast, all nine pups that received a mixture of virus and IFN were still alive on day 12 postinfection. Three of them developed poorly and died between days 13 and 16. The remaining six animals developed normally and showed no clinical symptoms until day 21, when the experiment was terminated (Fig. 2C). In contrast to the situation in newborn Mx1-positive mice, the beneficial effect of IFN was minimal in adult Mx1-negative mice. Injection of 100 μg of poly(I:C) (a potent IFN-inducing agent) into the peritoneums of such mice before infection with 100 PFU of THOV delayed disease onset by 1 to 3 days but usually did not prevent fatal disease (data not shown).

Our study with Mx1-positive mice thus clearly demonstrates that the ML protein is in fact a virulence factor that greatly enhances the pathogenic potential of THOV. As predicted from cell culture experiments (7), the ML protein seems to greatly limit the extent by which infected host cells can mount a full-scale innate immune response. The NS1 protein of influenza A virus, which represents the prototype IFN antagonistic factor encoded by another orthomyxovirus (5), affects many different host cell functions (14). It seems to inhibit efficient IFN gene expression mainly by sequestering viral double-stranded RNA and possibly by additional mechanisms (2, 14). It remains to be determined whether the ML protein uses similar or distinct mechanisms for suppression of IFN synthesis. Finally, our study demonstrates that it can be a challenging task to obtain firm experimental proof that a viral protein is critically involved in pathogen evasion of host defense. In our case, the virulence-enhancing effect of the THOV ML protein became apparent only after special strains of inbred mice were used at a critical age. It has become increasingly clear that inbred mouse strains do not fully represent the gene pool of the species but rather lack some pathogen-specific resistance traits found in wild mice (6). Thus, if putative virulence factors of other pathogens do not exhibit the predicted effects in one particular animal model, it is still possible that they will do so in an alternative experimental system.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Hiscott for providing vesicular stomatitis virus expressing green fluorescent protein.

This work was supported by grant KO 1579/3-5 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. A.P. was supported by a fellowship from the University of Veterinary Sciences, Vienna, Austria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boritz, E., J. Gerlach, J. E. Johnson, and J. K. Rose. 1999. Replication-competent rhabdoviruses with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coats and green fluorescent protein: entry by a pH-independent pathway. J. Virol. 73:6937-6945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donelan, N. R., C. F. Basler, and A. Garcia-Sastre. 2003. A recombinant influenza A virus expressing an RNA-binding-defective NS1 protein induces high levels of beta interferon and is attenuated in mice. J. Virol. 77:13257-13266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frese, M., G. Kochs, U. Meier-Dieter, J. Siebler, and O. Haller. 1995. Human MxA protein inhibits tick-borne Thogoto virus but not Dhori virus. J. Virol. 69:3904-3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gangemi, J. D., J. Lazdins, F. M. Dietrich, A. Matter, B. Poncioni, and H. K. Hochkeppel. 1989. Antiviral activity of a novel recombinant human interferon-alpha B/D hybrid. J. Interferon Res. 9:227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Sastre, A., A. Egorov, D. Matassov, S. Brandt, D. E. Levy, J. E. Durbin, P. Palese, and T. Muster. 1998. Influenza A virus lacking the NS1 gene replicates in interferon-deficient systems. Virology 252:324-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guenet, J. L., and F. Bonhomme. 2003. Wild mice: an ever-increasing contribution to a popular mammalian model. Trends Genet. 19:24-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagmaier, K., S. Jennings, J. Buse, F. Weber, and G. Kochs. 2003. Novel gene product of Thogoto virus segment 6 codes for an interferon antagonist. J. Virol. 77:2747-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haller, O., H. Arnheiter, I. Gresser, and J. Lindenmann. 1981. Virus-specific interferon action. Protection of newborn Mx carriers against lethal infection with influenza virus. J. Exp. Med. 154:199-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haller, O., M. Frese, D. Rost, P. A. Nuttall, and G. Kochs. 1995. Tick-borne Thogoto virus infection in mice is inhibited by the orthomyxovirus resistance gene product Mx1. J. Virol. 69:2596-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada, H., K. Willison, J. Sakakibara, M. Miyamoto, T. Fujita, and T. Taniguchi. 1990. Absence of the type I IFN system in EC cells: transcriptional activator (IRF-1) and repressor (IRF-2) genes are developmentally regulated. Cell 63:303-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horisberger, M. A., P. Staeheli, and O. Haller. 1983. Interferon induces a unique protein in mouse cells bearing a gene for resistance to influenza virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:1910-1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kochs, G., and O. Haller. 1999. Interferon-induced human MxA GTPase blocks nuclear import of Thogoto virus nucleocapsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2082-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotiranta-Ainamo, A., J. Rautonen, and N. Rautonen. 2004. Imbalanced cytokine secretion in newborns. Biol. Neonate 85:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krug, R. M., W. Yuan, D. L. Noah, and A. G. Latham. 2003. Intracellular warfare between human influenza viruses and human cells: the roles of the viral NS1 protein. Virology 309:181-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavlovic, J., H. A. Arzet, H. P. Hefti, M. Frese, D. Rost, B. Ernst, E. Kolb, P. Staeheli, and O. Haller. 1995. Enhanced virus resistance of transgenic mice expressing the human MxA protein. J. Virol. 69:4506-4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staeheli, P., R. Grob, E. Meier, J. G. Sutcliffe, and O. Haller. 1988. Influenza virus-susceptible mice carry Mx genes with a large deletion or a nonsense mutation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:4518-4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner, E., O. G. Engelhardt, S. Gruber, O. Haller, and G. Kochs. 2001. Rescue of recombinant Thogoto virus from cloned cDNA. J. Virol. 75:9282-9286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]