Abstract

Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD), the two most prevalent mental health disorders in the Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, are at increased risk for cannabis use and problems including cannabis use disorder (CUD). The present study examined the relationship of PTSD and MDD with cannabis use frequency, cannabis problems, and CUD as well as the role of three coping-oriented cannabis use motives (coping with negative affect, situational anxiety, and sleep) that might underlie this relationship. Participants were veterans (N = 301) deployed post 9/11/2001 recruited from Veterans Health Administration facility in the Northeast US based on self-reported lifetime cannabis use. There were strong unique associations between PTSD and MDD and cannabis use frequency, cannabis problems, and CUD. Mediation analyses revealed the three motives accounted, in part, for the relationship between PTSD and MDD with three outcomes in all cases but for PTSD with cannabis problems. When modeled concurrently, sleep motives, but not situational anxiety or coping with negative affect motives, significantly mediated the association between PTSD and MDD with use. Together with coping motives, sleep motives also fully mediated the effects of PTSD and MDD on CUD and in part the effect of MDD on cannabis problems. Findings indicate the important role of certain motives for better understanding the relation between PTSD and MDD with cannabis use and misuse. Future work is needed to explore the clinical utility in targeting specific cannabis use motives in the context of clinical care for mental health and CUD.

Keywords: cannabis, motives, PTSD, depression, sleep

Introduction

Prevalence rates of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder (CUD) have more than doubled in the past decade in the general population of United States (US) adults (Hasin et al., 2015) and among the US military veterans (Bonn-Miller, Harris, & Trafton, 2012). A growing number of veterans are also diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with PTSD prevalence rates of 23% among those returning from Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND) (Fulton et al., 2015). Although PTSD is the most common mental health diagnosis among OEF/OIF/OND veterans, more than 17% of returning veterans also meet criteria for a depressive disorder (Seal et al., 2009). The prevalence rates of these mental health disorders are disproportionately higher than the rates of PTSD and MDD in the general population (3.5% and 6.7%, respectively; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, Walters, 2005). Many service members with PTSD are also dually or multiply diagnosed (Cohen et al., 2010; Seal, Bertenthal, Miner, Sen, & Marmar, 2007), with major depressive disorder (MDD) being the second most current co-occurring psychiatric disorder (30% comorbidity with PTSD; Seal et al., 2008), followed by substance use disorders (SUDs; Golub, Vazan, Bennett, & Liberty, 2013; Seal et al., 2008; Seal et al., 2011). In fact, having either a PTSD or MDD diagnosis increased the odds of having any drug use disorder more than 3-fold in this veteran population (Seal et al., 2011).

Notably, population comorbidity estimates specific to cannabis use and CUD are not well-established among OEF/OIF/OND veterans because there is no routine screening or assessment for cannabis use or CUD in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA; Department of Veterans Affairs, 2009). Relative to many other comorbid psychiatric disorders (Agosti, Nunes, & Levin, 2002; Chen, Wagner, & Anthony, 2002; Conway, Compton, Stinson, & Grant, 2006), one study found that PTSD is the most prevalent co-occurring psychiatric disorder among veterans with CUD presenting to VHA, at 29% (Bonn-Miller et al., 2012). Similar to other SUDs, co-occurrence of CUD and PTSD is associated with greater PTSD symptom severity, decreased likelihood of CUD cessation, and worse PTSD and CUD clinical outcomes (Bonn-Miller et al., 2015; Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, & Drescher, 2011) as well as greater health services use relative to no comorbidity (Ouimette, Finney, & Moos, 1999; Saladin, Brady, Dansky, & Kilpatrick,1995; Watkins, Burnam, Kung, & Paddock, 2001).

Although the literature has been primarily focused on the comorbidity between PTSD and cannabis use and CUD (Cougle, Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, Zvolensky, & Hawkins, 2011; Kevorkian et al., 2015), depression appears to also co-occur with cannabis use problems and dependence in both general population (Chen et al., 2002; Degenhardt, Hall, & Lynskey, 2003; Feingold, Fox, Rehm, & Lev-Ran, 2015; Grant et al., 2006) and in veterans (Farris, Zvolensky, Boden, & Bonn-Miller, 2014; Goldman et al., 2010). However, the relative roles of MDD and PTSD with respect to cannabis use and problems have not been examined. Given that MDD is more prevalent than other mental health disorders in terms of its co-occurrence with PTSD among returning veterans (Seal et al., 2011), it is presently unclear whether increased risk of cannabis misuse is unique to PTSD symptomatology relative to MDD and whether the mechanisms that explain the pathways from PTSD and MDD to cannabis-related problems and CUD are similar.

Mechanisms underlying associations between PTSD, MDD, and cannabis outcomes

Individuals with affective vulnerabilities, such as PTSD and MDD, are especially likely to use cannabis as a means of coping (Boden, Babson, Vujanovic, Short, & Bonn-Miller, 2013; Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, Feldner, Bernstein, & Zvolensky, 2007a; Buckner & Zvolensky, 2014; Bujarski, Norberg, & Copeland, 2012; Johnson, Mullin, Marshall, Bonn-Miller, & Zvolensky, 2010; Mitchell, Zvolensky, Marshall, Bonn-Miller, & Vujanovic, 2007; Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005). In fact, there is broad-based evidence that cannabis may be used by some persons with clinical disorders or individual differences in affective vulnerability factors as an (short-term) emotion regulatory strategy to reduce or manage perceived aversive psychological and mood states (Metrik, Kahler, McGeary, Monti, & Rohsenow, 2011). For example, emotionally vulnerable cannabis users may rely on cannabis to decrease distress (Potter, Vujanovic, Marshall-Berenz, Bernstein, & Bonn-Miller, 2011), or to cope with symptoms of anxiety and PTSD (Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, & Zvolensky, 2008b; Bonn-Miller et al., 2007a; Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2007b; Buckner, Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2007), which, may in turn theoretically be related to greater problematic cannabis use and CUD (Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009; Farris, Metrik, Bonn-Miller, Kahler, & Zvolensky, in press; Moitra, Christopher, Anderson, & Stein, 2015). Indeed, cannabis coping motives mediate the relation between different indices of affective vulnerability (e.g., anxiety sensitivity, distress intolerance, social anxiety) implicated in the etiology of mood and anxiety disorders and a range of cannabis outcomes, including cannabis use frequency (Johnson, Bonn-Miller, Leyro, & Zvolensky, 2009), severity of cannabis problems (Buckner & Zvolensky, 2014; Bujarski et al., 2012), and cannabis dependence (Johnson et al., 2010) in non-veteran samples.

Importantly, coping to relieve PTSD-related negative affect and distress has been established as a powerful motivator for cannabis use among non-veteran users (Bonn-Miller et al., 2007a; Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, Boden, & Gross, 2011; Bujarski et al., 2012; Potter et al., 2011) and veterans (Boden et al., 2013; Bremner, Southwick, Darnell, & Charney, 1996). Two veteran studies have shown that cannabis expectancies about anticipated benefits of cannabis use, a construct conceptually related to motives (Cox & Klinger, 1988), mediated the relation between symptoms of PTSD and cannabis use in an internet survey of combat veterans (Earleywine & Bolles, 2014), and the relation between depressive symptoms and cannabis use among cannabis dependent military veterans (Farris et al., 2014). Other work suggests the remission of PTSD symptoms is associated with a 75% or greater reduction in drug and alcohol use days, but reduction in SUD symptoms does not improve PTSD symptoms (Hien et al., 2010). Conversely, lower levels of change in PTSD symptom severity after PTSD treatment was associated with increased use of cannabis post discharge (Bonn-Miller et al., 2011).

In contrast to other cannabis use motives (e.g., enhancement, social) that are associated with non-problem patterns of cannabis use, motives broadly related to coping with negative affect are specifically linked with heightened cannabis use, including cannabis-related problems and CUD (Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009; Bonn-Miller, Boden, Bucossi, & Babson, 2014; Moitra et al., 2015; Simons et al., 2005). Cognitive-motivational factors related to coping and avoidance of social situations have also been linked with cannabis use and related problems (Buckner & Zvolensky, 2014). However, using cannabis specifically as a means of managing sleep problems has received far less attention; yet, sleep disturbance is a prominent symptom of both PTSD and MDD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In particular, veterans with PTSD suffer from chronic sleep disturbance (Lavie, Katz, Pillar, & Zinger, 1998; Woodward, Arsenault, Murray, & Bliwise, 2000), and thus, may be using cannabis to help cope with sleep problems in the short-term, particularly because cannabis can produce sedation (Lamarche & De Koninck, 2007; Stewart, Pihl, & Conrad, 1998; Vandrey, Babson, Herrmann, & Bonn-Miller, 2014). Although not yet examined among veterans, Bonn-Miller and colleagues (Bonn-Miller, Babson, & Vandrey, 2014a; Bonn-Miller, Boden, Bucossi, & Babson, 2014b) found that medical cannabis users with elevated PTSD symptoms, relative to those with lower PTSD scores, were more likely to use cannabis to improve sleep and used cannabis more frequently. Specifically, sleep but not coping motives interacted with PTSD symptoms to predict frequency of cannabis use. In the overall sample, coping and other motives (boredom, alcohol, enjoyment, celebration, altered perception, social anxiety, availability, and experimentation) but not sleep motives were associated with cannabis problems. Given the dearth of studies on sleep motives in veterans but well-established sleep dysfunction in those with PTSD and MDD, we would expect sleep to be a prominent motive for using cannabis among this population.

Present Study

Past work has not evaluated the affective-motivational model, which emphasizes the central role of negative affect in motivating drug use (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Simons et al., 2005), as applied to cannabis use motives as mediators of the relation between PTSD and MDD with cannabis use problems or CUD among veterans. Furthermore, extant studies linking PTSD or MDD with cannabis use severity lack specificity in terms of using cannabis to cope with negative affect vs. using to cope with sleep problems that are highly prevalent among veterans with PTSD and MDD. The present study addresses these critical gaps in knowledge in an OEF/OIF/OND sample of lifetime cannabis users with a full range of cannabis involvement (frequency of use ranging from lifetime to current weekly/daily use). The first novel aim was to concurrently examine the relative roles of PTSD and MDD on multiple indicators of cannabis use including cannabis use frequency, cannabis-related problems, and diagnosis with past 12-month DSM-5 CUD. Based on prior work (e.g., Boden et al., 2013;; Earleywine & Bolles, 2014; Farris et al., 2014), we hypothesized that each affective disorder will be significantly associated with each of the three cannabis use indices. The hypotheses pertaining to the strength of the association of PTSD relative to MDD with the cannabis outcomes were exploratory given these predictors have not been previously examined concurrently in one comprehensive study.

The second novel aim was to specifically examine the mediating role of coping motives relative to sleep and anxiety motives as pathways between PTSD and MDD and cannabis use outcomes in one comprehensive multivariate model. Based on findings from research that investigated individual components of our multivariate model (e.g., Boden et al., 2013; Bonn-Miller et al., 2007a; Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, & Zvolensky, 2008b; Earleywine & Bolles, 2014),we hypothesized that the three motives would significantly mediate the relations of PTSD and MDD with the three dependent variables. Furthermore, sleep and coping motives were expected to have a stronger influence than situational anxiety motives in explaining the relation between MDD and cannabis indices.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Participants were OEF/OIF/OND veterans deployed post 9/11/2001 eligible for the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) at least 18 years old; (b) an OEF/OIF/OND veteran as confirmed by the Providence VHA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS); and (c) used cannabis at least once in his/her lifetime. Exclusion criteria were: (a) suicidal risk in the past two weeks ascertained with items from the Suicidality Scale of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (Watson et al., 2007) and clinical interview; (b) psychotic symptoms in the past month assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Non-Patient Edition (SCID-IV-NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002); (c) score ≤ 23 on the Mini-Mental Status Exam (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975); or (d) active duty at the time of the baseline assessment (due to increased likelihood of study dropout due to deployment). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Brown University and the Providence VHA.

Participants were recruited from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facility in Providence, RI between February 2013 and December 2015. In addition to study advertisements at the Providence VHA, veterans were recruited by utilizing the VHA OEF/OIF/OND Roster, an accruing database of combat veterans who have recently returned from military service in Iraq and Afghanistan and enrolled in VHA. Using the Roster, study information was mailed to potential participants in RI, MA, and CT. Veterans could indicate lack of interest in being contacted for the screening by mailing back a pre-addressed, stamped do-not-contact postcard (4.6% of all mailings). Veterans were screened for eligibility by telephone (53% of all outreach calls made) and were invited to complete a baseline interview, at which time they signed informed consent, completed the in-person screening survey, and completed assessments for the baseline portion for this ongoing prospective study. Of the 830 individuals screened for the study, 35% (n = 292) did not meet preliminary inclusion/exclusion criteria and nearly 26% (n = 213) were eligible but did not show for the baseline assessment (n = 154), declined to participate in the study (n = 32), or asked to be contacted in the future (n = 27). Twenty one eligible screeners were scheduled for a future study appointment. Of the 304 enrolled in the study, three were deemed ineligible at baseline. Thus, results are based on 301 participants.

The baseline assessment consisted of a battery of interview and self-report assessments and a urine toxicology screen for cannabis. Zero breath alcohol concentration was verified with an Alco-Sensor IV (Intoximeters, Inc., St Louis, MO., USA) to ensure validity of the assessment. All participants were compensated $50 upon completion of the study session.

Measures

Demographic Information

Demographic and background information, such as sex, ethnicity, marital status, employment, branch of service, location and number of deployments (OEF/OIF/OND) was collected at baseline and verified through CPRS.

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995) is a semi-structured interview used to assess for lifetime and past month DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis. Participants were scored for frequency (score ≥ 1) and intensity (score ≥ 2) of symptoms using established diagnostic guidelines (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). Depending on whether they met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, participants were then assigned a lifetime and past month dichotomous diagnosis score (1 = PTSD, 0 = No PTSD).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP) was used to determine diagnosis of lifetime and current (past month) MDD (First et al., 2002). No modifications were necessary to ascertain DSM-5 MDD diagnoses following the release of DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) as the criteria for MDD did not change.

DSM-5 diagnosis of lifetime and current (past year) CUD was also determined with the SCID-NP. With the release of DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), legal problems diagnostic criterion was excluded and items assessing cannabis withdrawal and craving were included. Participants endorsing two or more of the 11 symptoms in the past year met criteria for current DSM-5 CUD.

Cannabis-related problems were assessed with the Marijuana Problems Scale (MPS) (Stephens, Roffman, & Curtin, 2000), a self-report 22-item questionnaire that evaluates problems experienced in the past 90 days related to cannabis use. A total count of combined minor and serious problems was used rather than a severity score (only 4.6% endorsed major problems).

The MPS has strong internal consistency (Peters, Nich, & Carroll, 2011; Stephens et al., 2000); in this sample it was excellent (α = .92).

Cannabis Use

The Time-Line Follow-Back Interview (TLFB) (Dennis, Funk, Harringon, Godley, & Waldron, 2004; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was conducted at baseline for the 6 months prior to the visit, and used to characterize the sample in terms of percent days cannabis use. In addition to TLFB, all participants were assessed for lifetime cannabis use (study eligibility criterion) and use in the past year. Based on their TLFB interview and endorsement of past year cannabis use, participants were classified into the following three use frequency categories: lifetime user (no past year use, n = 181), past-year user (using less than two times a week) (n = 60), and frequent user (at least two or more times a week) (n = 60); with the latter group reflective of regular heavy patterns of use. Frequent users reported using cannabis on an average of 74.5 (SD = 33.7) percent of days on the TLFB relative to past-year users, 11.8 (SD = 17.2) percent of days.

The Comprehensive Marijuana Motives Questionnaire (CMMQ)

Participants rated on a 1 = “almost never/never” to 5 = “almost always/always” scale how often they used cannabis for each of 36 reasons; three items per subscale were used to derive a mean composite score for 12 different motives (Lee, Neighbors, Hendershot, & Grossbard, 2009). Consistent with the affective-motivational model in the present study, only the coping (e.g., “because you were depressed”, “to forget your problems”), social (henceforth situational) anxiety (e.g., “because it relaxes you when you are in an insecure situation”), and sleep (e.g., “because you are having problems sleeping”) cannabis use motives were studied. Internal consistencies for the 3 factors were good (α = .84 to .91).

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989) is a psychometrically sound self-report questionnaire for assessing sleep quality and disturbances over a one month period (Carpenter & Andrykowski, 1998). A global PSQI score greater than 5 indicates poor sleep quality (Buysse et al., 1989). PSQI was used descriptively to characterize sleep patterns in this sample.

Data Analytic Strategy

First, preliminary descriptive analyses were conducted including examining cannabis use motives as a function of diagnosis of PTSD, MDD, and CUD as well as correlations among all predictor and outcome variables. Regression analyses were performed to test the effects of PTSD and MDD on: (a) cannabis use (b) number of cannabis-related problems, and (c) CUD. Ordinal logistic regression was used for the three-level cannabis use variable, Poisson regression was used to examine predictors of the count variable (cannabis problems), and logistic regression was used for CUD. The two predictors were simultaneously entered, covarying for age, as age has been shown to be an important factor related to both drug use and PTSD diagnosis among veterans (Seal et al., 2007; Seal et al., 2011). Sex and marital status were initially also covaried, but were subsequently dropped from all analyses because they were not associated with any outcomes. We also tested whether the effects of the two predictors significantly differed from each other using the Wald test of parameter constraints. Finally, we tested the mediating role of cannabis use motives in the association between diagnoses of PTSD and MDD and the three cannabis outcome variables. Each mediator was first tested in a separate model, for each of the three cannabis outcomes (9 models); then, mediators were entered simultaneously in one model for each of the three criterion variables (3 models) to test whether the associations remained with the other motives in one model. Additionally, within this final model we tested whether the three indirect effects significantly differed from one another. To conduct the tests, the indirect effect for each mediator was computed by taking the product of the “a” path (predictor to mediator) and the “b” path (mediator to outcome); a Wald test of parameter constraints tested whether these product terms were significantly different from each other. Thus, a total of 12 mediational models were tested. All models included the direct effect of the diagnosis and the outcome variable. Models were conducted using Mplus Version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012). Mediation was tested using the delta method for the indirect effect (MacKinnon, 2008).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The sample was predominantly male with a mean age of 33.4 (SD = 9.5) years (see Table 1). The median annual family income bracket of participants was $40,000-49,000; 20.3% were unemployed; and 46.8% were married or cohabiting. The average percent of drinking days was 25.6 (SD = 29.7) with participants consuming an average of 4.6 (SD = 3.6) drinks per drinking day. Tobacco smokers (n = 136) reported cigarette use an average of 78.4% (SD = 33.8) of days, and averaged 11.3 (SD = 7.7) cigarettes per day on smoking days.

Table 1.

Sample demographics, diagnostic, and military service-related characteristics (N = 301)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 285 | 94.7 |

| Race | ||

| White | 244 | 81.1 |

| Black/African American | 11 | 3.7 |

| Asian | 5 | 1.7 |

| Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander | 2 | .7 |

| Multiracial/Other | 38 | 12.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino(a) | 38 | 12.6 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single/Never Married | 95 | 31.6 |

| Married/Living with partner | 141 | 46.8 |

| Divorced/Separated | 65 | 21.6 |

| Employment Statusa | ||

| Employed | 233 | 77.4 |

| Unemployed/Home-maker | 61 | 20.3 |

| Student | 71 | 23.6 |

| Military service | 83 | 27.6 |

| Combat Operation(s) Served Ina | ||

| Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) | 225 | 74.8 |

| Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) | 160 | 53.2 |

| Operation New Dawn (OND) | 61 | 20.3 |

| Most Recent Branch of Service | ||

| Army | 220 | 73.1 |

| Marines | 35 | 11.6 |

| Air Force | 24 | 8.0 |

| Navy | 21 | 7.0 |

| Coast Guard | 1 | .3 |

| THC Positive Toxicology Screen | 65 | 21.6 |

| Major Depressive Disorder, Current | 46 | 15.3 |

| Major Depressive Disorder, Lifetime | 150 | 49.8 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Current | 41 | 13.6 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Lifetime | 78 | 25.9 |

| Cannabis Use Disorder, Current | 47 | 15.6 |

| Cannabis Use Disorder, Lifetime | 119 | 39.5 |

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 33.4 | 9.5 |

| Years of Education Completed | 13.7 | 2.0 |

| Number of deployments post-9/11/2001 | 1.8 | 1.1 |

| Years since last deployment | 3.7 | 2.5 |

| Global PSQI score | 8.9 | 4.1 |

Note.

Multiple responses permitted.

The three cannabis use frequency groups did not significantly differ by sex (p = .19), race (p = .69), or ethnicity (p = .82). Lifetime users were significantly older (M =35.66, SD = 10.23) than past-year (M = 30.23, SD = 7.42) and frequent users (M = 29.83, SD = 6.56; F [2, 298] = 13.87, p < .001). Tables 2a and 2b display sample distribution by PTSD diagnosis (No PTSD, PTSD) and MDD diagnosis (No MDD, MDD) within CUD (Table 2a) and each of the cannabis use frequency groups (Table 2b). Levels of cannabis use motives and outcomes as a function of PTSD and MDD are shown in Table 3.

Table 2a.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by major depressive disorder (MDD) by cannabis use disorder (CUD)

| CUD |

No CUD |

Totals |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No MDD | MDD | No MDD | MDD | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n | |

| PTSD | 8 (26.7) | 8 (47.1) | 13 (5.8) | 12 (41.4) | 41 |

| No PTSD | 22 (73.3) | 9 (52.9) | 212 (94.2) | 17 (58.6) | 260 |

| Total | 30 (100) | 17 (100) | 225 (100) | 29 (100) | 301 |

Table 2b.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by major depressive disorder (MDD) by cannabis use frequency

| Frequent Use |

Past-Year Use |

Lifetime Use |

Totals |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No MDD | MDD | No MDD | MDD | No MDD | MDD | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n | |

| PTSD | 9 (23.1) | 12 (57.1) | 2 (3.8) | 3 (42.9) | 10 (6.1) | 5 (27.8) | 41 |

| No PTSD | 30 (76.9) | 9 (42.9) | 51 (96.2) | 4 (57.1) | 153 (93.9) | 13 (72.2) | 260 |

| Total | 39 (100) | 21 (100) | 53 (100) | 7 (100) | 163 (100) | 18 (100) | 301 |

Table 3.

Comparisons of cannabis use motives and outcomes as a function of diagnosis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD).

| No PTSD | PTSD | No MDD | MDD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | t-test | d | M (SD) | M (SD) | t-test | d | |

| Coping Motives | 1.51 (0.93) | 2.25 (1.19) | 4.55*** | .69 | 1.50 (0.90) | 2.25 (1.28) | 4.84*** | .68 |

| Sleep Motives | 1.80 (1.19) | 2.87 (1.49) | 5.15*** | .79 | 1.82 (1.23) | 2.65 (1.40) | 4.15*** | .63 |

| Situational Anxiety Motives | 1.54 (0.88) | 2.24 (1.22) | 4.41*** | .66 | 1.54 (0.88) | 2.17 (1.23) | 4.16*** | .59 |

| Cannabis-related Problems | .98 (2.63) | 1.98 (3.56) | 2.14* | .32 | .81 (2.36) | 2.76 (4.14) | 4.49*** | .58 |

| % | % | χ 2 | OR | % | % | χ 2 | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis Use | 28.9*** | 22.47*** | ||||||

| Lifetime Users a | 64.1 | 36.6 | 64.2 | 39.1 | ||||

| Past Year Users | 20.8 | 12.2 | 1.02 | 20.5 | 15.2 | 1.22 | ||

| Frequent Users | 15.1 | 51.2 | 5.96 | 15.4 | 45.7 | 4.88 | ||

| Cannabis Use Disorder | 11.9 | 39.0 | 19.74*** | 4.73 | 11.8 | 37.0 | 18.77*** | 4.40 |

Notes. d = Cohen's d

reference group

OR = odds ratio; Results are based on t-tests and chi-square tests.

p <.05

** p < .01

p <.001

Association Between PTSD, MDD, and the Cannabis Dependent Variables

Bivariate correlations are presented in Table 4. The PTSD and MDD variables were significantly positively associated with each other. Both PTSD and MDD were positively significantly associated with cannabis use motives. The three cannabis use motives were significantly positively associated with all three criterion variables. The criterion variables were significantly intercorrelated (medium to large sized associations). Importantly, there were correlations in the small-to-medium size range among the predictors (PTSD and MDD) and outcomes, including significant but small-sized correlation between PTSD and problems.

Table 4.

Correlations among variables

| 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | .37** | .25** | .29** | .25** | .27** | .12* | .26** | −.07 |

| 2. Major depressive disorder | .27** | .23** | .23** | .25** | .25** | .25** | −.01 | |

| 3. Coping Motives | .56** | .61** | .37** | .32** | .38** | −.09 | ||

| 4. Sleep Motives | .60** | .61** | .32** | .44** | −.28** | |||

| 5. Situational Anxiety Motives | .37** | .22** | .27** | −.11 | ||||

| 6. Cannabis use | .33** | .62** | −.27** | |||||

| 7. Cannabis-related problems | .40** | −.08 | ||||||

| 8. Cannabis use disorder | −.14* | |||||||

| 9. Age | - |

Notes.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

***p ≤ .001.

Correlations among continuous variables are Pearson correlations; correlations among categorical variables are phi coefficients, and correlations between continuous and categorical variables are point-biserial correlations. For the purposes of the correlation matrix, cannabis use was treated as a continuous variable, although it is treated as an ordered categorical variable in regression analyses.

Next, we conducted regression analyses to examine the effects of PTSD and MDD on the three dependent variables, controlling for age. Findings indicated that PTSD and MDD each were significantly associated with greater cannabis use (OR=1.75, 95% CI: 1.22, 2.52, p < .01; OR=1.65, 95%: 1.17, 2.33, p < .01 respectively); and the two predictors did not significantly differ from each other, Wald χ2 (1, N = 301) = 0.04, p = .83. Similarly, PTSD and MDD both uniquely predicted the likelihood of being diagnosed with a CUD (OR=1.71, 95% CI: 1.14, 2.59, p ≤ .01; OR= 1.78, 95% CI: 1.19, 2.66, p < .01 respectively); and the two predictors did not significantly differ from each other, Wald χ2 (1, N = 301) = 0.01, p = .91. In the model predicting cannabis problems, there was a significant main effect for MDD but not PTSD, such that diagnosis of MDD was significantly associated with greater number of cannabis problems (b = .59, SE = .06, β =.84; p < .001); these effects significantly differed from each other, Wald χ2 (1, N = 299)= 21.66, p < .001.

Mediation Results

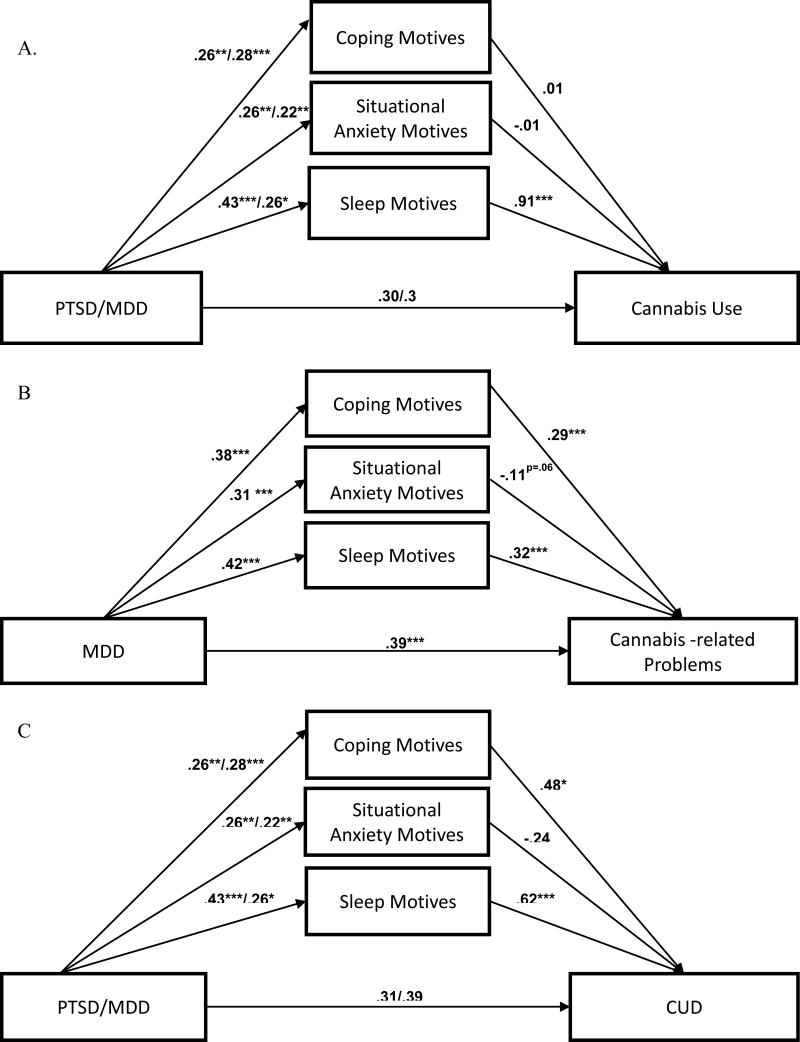

Finally, we conducted a set of mediation models for each of the three outcomes (see Figure 1). Mediation of the association between PTSD and cannabis problems was not tested due to lack of significant association between PTSD and the criterion in the multivariate model. Results are presented in Table 5.

Figure 1.

Mediation analysis of the relation between PTSD/MDD and cannabis use (Panel A), cannabis-related problems (Panel B), and cannabis use disorder (Panel C).

Table 5.

Indirect and direct effects for the mediation of the association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) with cannabis use, cannabis-related problems, and cannabis use disorder (CUD), by three cannabis use motives.

| Cannabis Use | Cannabis-related Problems | CUD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis Use Motives | PTSD | MDD | MDD | PTSD | MDD |

| Single mediator | |||||

| Coping | .14 (26%)* | .16 (31%)** | .16 (27%)*** | .18 (31%)* | .20 (32%)** |

| Situational anxiety | .18 (26%)* | .13 (26%)* | .09 (16%)*** | .12 (22%) * | .10 (17%)* |

| Sleep | .39 (57%)*** | .24 (43%)* | .17 (28%)*** | .31 (51%)** | .19 (29%)* |

| Multiple mediators | |||||

| Total indirect effect | .39 (57%)*** | .24 (43%)* | .21 (35%)*** | .33 (52%)*** | .25 (39%)** |

| Coping | .004 (1%) a | .004 (1%) a | .11 (18%) a *** | .13 (20%) a p=.054 | .14 (21%) a * |

| Situational anxiety | −.003 (0%) a | −.003 (0%) a | −.04 (0%) b | −.06 (0%) b | −.05 (0%) b |

| Sleep | .39 (57%) b *** | .24 (43%) b * | .13 (22%) a *** | .27 (42%) a ** | .16 (26%) a * |

| Direct effect | .30 | .32 p=.095 | .39*** | .31 | .39 p=.09 |

Notes. Parameters are unstandardized. All models control for age. Mediation of the association between PTSD and cannabis-related problems was not tested due to lack of significant association between the predictor and the criterion. Indirect effects sharing common subscripts did not significantly differ from each other.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001

Cannabis use frequency

In separate single mediator models (top panel of Table 5), there was a significant indirect effect of PTSD and MDD through each use motive on cannabis use frequency; inclusion of each mediator accounted for a sizeable portion of the effects of PTSD and MDD on the dependent variables (between 26% and 57% for PTSD; between 26% and 43% for MDD). In the multiple mediator model (bottom panel of Table 5), the indirect effect of PTSD and MDD through sleep motives on cannabis use was significant and accounted for 57% and 43% of the total effect, respectively. The indirect effects of PTSD and MDD through coping and situational anxiety motives were nonsignificant (and did not differ from each other), indicating that these motives did not mediate the effects of the affective disorders when sleep motives were also in the model. Furthermore, with cannabis use motives in the model predicting cannabis use frequency, the direct effects of PTSD and MDD were nonsignificant, indicating full mediation.

Cannabis problems

In separate single mediator models, there was a significant indirect effect of MDD through each use motive on cannabis problems, indicating that each motive was a partial mediator of MDD; the indirect effect through each motives variable accounted for between 16% and 28% of the total effect. In the multiple mediator model, the indirect effects of MDD through sleep and coping motives on cannabis problems were significant (percent mediated was 22% and 18%, respectively); these indirect effects were similar in magnitude and did not significantly differ from each other. In contrast, the indirect effects of MDD through situational anxiety motive was nonsignificant, indicating that this motive did not mediate the effects of MDD when the other two motives were also in the model. There was still a significant direct effect between MDD and problems, even after accounting for mediators in the model, thus suggesting that there was only partial mediation.

CUD

In separate single mediator models, there were significant indirect effects of PTSD and MDD through each motive on CUD, with each mediator accounting for between 17% and 51% of the total effect. In the multiple mediator model, the indirect effects of MDD through sleep and coping motives on CUD were significant and accounted for 26% and 21% of the variance, respectively. The indirect effect of PTSD through sleep motive also was significant, accounting for 42% of the variance, and through coping was at trend level (p =.054), accounting for 20% of the total effect. The indirect effects of PTSD and MDD through situational anxiety motive were nonsignificant, indicating that this motive did not mediate the effects of disorders when the other two motives were also in the model. The indirect effect for situational anxiety motives significantly differed from those of coping and sleep motives, which did not significantly differ from each other. With cannabis use motives in the model predicting CUD, the direct effects of PTSD and MDD were nonsignificant, indicating full mediation.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the affective-motivational model of substance use with coping-oriented cannabis use motives including coping with negative affect, situational anxiety, and sleep problems as mediators of the relation between PTSD and MDD with cannabis use, related problems, and CUD. Results indicated that MDD was significantly associated with all three cannabis use indices; PTSD was significantly associated with cannabis use and CUD. Both mental health disorders were significantly associated with all three cannabis use motives. In support of our hypotheses, there was evidence of coping-oriented reasons for use explicating these relations of the MDD and PTSD with greater frequency of cannabis use or with CUD. Furthermore, specific cannabis use motives related to managing sleep and coping with negative affect had stronger influence than situational anxiety motives on veterans’ risk for cannabis misuse when tested simultaneously. Finally, comparison of the relative pathways of PTSD and MDD with the indices of cannabis use revealed the unique and overall equivalent predictive roles of the two disorders in increasing likelihood of cannabis use and CUD.

The present study replicates the findings from prior studies that support the central role of cannabis coping motives in PTSD (Boden et al., 2013; Bonn-Miller et al., 2011; Bremner et al., 1996; Bujarski et al., 2012; Potter et al., 2011) and more broadly in emotional dysregulation (Bonn-Miller et al., 2008b; Bonn-Miller et al., 2007; Zvolensky et al., 2009) among cannabis users. We extended these findings on coping with negative affect to the other two more specific coping-oriented reasons: using cannabis to manage sleep problems and to avoid situational anxiety. Each of these motives appears to directly map onto the clinical presentation of PTSD and MDD. The situational anxiety and sleep relations are consistent with prior research demonstrating that lower levels of subjective improvement in PTSD symptoms of avoidance and hyperarousal are associated with increased risk of cannabis use in veterans (Bonn-Miller et al., 2011). The relationship between MDD and cannabis use via cannabis use motives observed here differ from past work focused on depressive symptoms among non-veteran samples of young adult cannabis users (Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, Bernstein, & Stickle, 2008a; Johnson et al., 2009), potentially due to the sample type (e.g., severity). In both of these studies, self-reported depressive symptoms were significantly associated with cannabis coping motives but not with past month cannabis use frequency.

In the multiple mediator models, sleep motives emerged as a dominant factor in explicating the relations between each of the two affective disorders with cannabis use. Specifically, using cannabis to manage sleep disturbance fully mediated the effect of both PTSD and MDD on frequency of cannabis use. Together with motives broadly related to coping with negative affect, sleep motives also fully mediated the effects of PTSD and MDD on increased risk of CUD and partially mediated the effect of MDD on cannabis-related problems. These findings are consistent with one prior study with medical marijuana users that showed sleep, but not coping motives, were associated with symptoms of PTSD and increased cannabis use (Bonn-Miller et al., 2014a). The novel aspect of the current study, however, is extending these findings to the diagnosis of MDD and to cannabis use outcomes across the full spectrum from frequency of use to cannabis-related problems to CUD.

Situational anxiety motive did not mediate the association between the affective disorders and the three indices of cannabis use in the multiple mediator models. Using cannabis as a means of managing situational or social anxiety may be closely related to the PTSD's avoidance symptoms, as demonstrated in the single mediator models. However, in line with our hypothesis,sleep and coping with negative affect appear to be more salient motives to use cannabis in veterans with PTSD and MDD. Future studies should consider examining the construct validity of the situational (social) anxiety motives of the CMMQ in relation to social and other anxiety disorders. Alternative motivational processes underlying the relation between cannabis use and affective disorders could also be explored.

The analysis of different types of motives for using cannabis has several significant clinical implications. For instance, omitting sleep when discussing cannabis use in clinical samples, especially in veterans, may result in missing an important underlying reason for why individuals are using cannabis and why they may be ambivalent about quitting use. Pharmacological properties of cannabis are conducive to sedation and relaxation (Bonn-Miller et al., 2014a), which could translate to subjective perception of improved sleep onset by many cannabis users (Conroy & Arnedt, 2014) and may also explain its widespread use among veterans with PTSD, MDD, and sleep disturbances. Nevertheless, cannabis, particularly at high doses, may not be beneficial to sleep as it disrupts sleep architecture including decreased REM and slow wave sleep, and increased sleep onset latency (Gates, Albertella, & Copeland, 2014; Garcia & Salloum, 2015). Furthermore, withdrawal from cannabis results in significantly disturbed sleep in the majority of heavy cannabis users (Budney, Hughes, Moore, & Vandrey, 2004), which subsequently places abstinent users at greater risk for relapse (Vandrey et al., 2014). Engaging veterans who use cannabis in evidence-based treatments that address sleep, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I; Morin et al., 2006; Perlis, Jungquist, Smith, & Posner, 2006), may have high impact on clinical outcomes for PTSD and CUD (Babson, Ramo, Baldini, Vandrey, & Bonn-Miller, 2015). The present findings also suggest targeting coping motives in the context of integrated behavioral treatments for CUD and PTSD as well as MDD may be useful. Comorbid treatments that specifically focus on coping skills for mood and stress management (Buckner et al., 2014) or increase an individual's tolerance for emotional distress and decrease avoidance of distress via cannabis use (Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, Twohig, Medina, & Huggins, 2010) may be particularly effective in veterans with CUD and cooccurring PTSD/MDD.

Identifying theory-driven mechanisms that maintain the association between the two most prevalent affective disorders in veterans and cannabis use will also help improve the screening procedures currently in place in clinical settings to detect cannabis misuse as early as possible, which has the potential to increase early intervention. A short screener that assesses cannabis consumption, problems, dependence, and perhaps even psychological sequelae might be warranted (e.g., the Cannabis Use Disorders Test, Adamson et al., 2010). Cannabis users may develop problems all along a continuum ranging in severity of negative consequences (e.g., procrastination, low energy, memory problems, sleep problems on the lower end of the spectrum) to more severe problems, consistent with CUD (e.g., loss of control over drug use) (Piomelli, Haney, Budney, & Piazza, 2016). Clinically, this distinction has great utility as screening for cannabis-related problems (in addition to CUD) may facilitate a therapeutic intervention by tapping into problem areas that help elicit motivation for changing cannabis use. Naturally, effective screening and discussion will not occur if providers are hesitant or unsure of how to assess cannabis use for reasons such as current political and legal climate regarding medical marijuana, use of cannabis to alleviate mental health conditions that have been caused or exacerbated by military service, stigma related to military regulations of substance use, or feeling that one lacks the expertise or education on cannabis use and treatments (Bujarski et al., 2016).

The strengths of the current study include a large veteran sample and selecting on lifetime cannabis use and therefore permitting the examination of the full spectrum from lifetime to problem/dependent end. Consistent with prior reports on the comorbidity of CUD with PTSD (Bonn-Miller et al., 2012), 34% of veterans with CUD in the current sample had co-occurring PTSD and similarly 36% had co-occurring MDD, while 17% were comorbid for CUD-PTSDMDD. Although CUD prevalence estimates are not well-established among OEF/OIF/OND veterans, the current sample rate of 15.6% exceeds the CUD estimate of 10% in the general non-veteran population of lifetime cannabis users (Hasin et al., 2015). This sample was also comparable in terms of PTSD and MDD rates (Fulton et al., 2015; Seal et al., 2009) and age, gender, and other demographic characteristics to other OEF/OIF samples (e.g., Cohen et al., 2009; Seal et al., 2007; Seal et al., 2011) but younger than studies based on veterans from other eras, treatment-engaged (e.g., PTSD in Bonn-Miller et al., 2012), or selected based on presence of a substance use disorder (e.g., CUD in Boden et al., 2013). Another strength was the use of interview-based “gold standard” diagnostic measures for PTSD, MDD, and CUD. Cannabis use status was biochemically verified with the urine toxicology screen. Furthermore, prior research linking PTSD or depression with cannabis use severity lacked specificity in terms of using cannabis to cope with negative affect and other symptoms vs. using to specifically cope with sleep problems highly prevalent among veterans with PTSD and MDD. This study found specific motives of coping with negative affect, situational anxiety and sleep problems to underlie the PTSD and MDD relationship with cannabis use and misuse, especially sleep motives.

However, the findings of the study must be considered in the context of some limitations and may not generalize to all OEF/OIF/OND veterans who are using the VHA for health care services. In this initial examination, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences about the association between the affective disorders and cannabis use outcomes. Nevertheless, similar to the temporal relation between PTSD and CUD (e.g., Hien et al., 2010), MDD is typically found to precede CUD and contribute to its etiology (Agosti et al., 2002; Conway et al., 2006). Our continuing longitudinal study, which was designed to assess these variables at independent time points, will help clarify the temporal sequencing of these relations and examine cannabis use motives as mediators. Longitudinal models will also help test specific hypotheses for current vs. lifetime users with respect to potentially different mechanisms underlying the relationship of PTSD and MDD with CUD and cannabis problems. Next, a small number of female veterans in our sample limited the generalizability of our findings and resulted in low power to detect any possible gender differences in motivational processes linking affective disorders with cannabis use. For example, previous research with non-veterans have found gender differences in coping motives mediating the relationship between distress tolerance and cannabis use (Bujarski et al., 2012). Multiple statistical tests were conducted in the present analyses, which may have inflated the risk of Type I error. While the risk of Type I error was likely mitigated to a large degree by our theory-based approach and a priori hypotheses, replication is needed to further substantiate these findings. Next, similar to other recent studies (e.g., Bonn-Miller et al., 2015) we employed DSM-IV criteria for PTSD diagnosis due to the timing of the study relative to the transition to DSM-5 version. Replication studies using DSM-5 criteria for PTSD may be needed. Finally, although interviewers were trained in the reliable use of the SCID and the CAPS diagnostic instruments and were required to demonstrate competence and adherence, inter-rater reliability ratings of the diagnoses were not conducted in the present study.

In conclusion, despite the coping-oriented premise for cannabis use steering a number of US states to legalize medical cannabis as treatment for individuals with PTSD (the only psychological condition among other medical conditions sanctioned for medical marijuana use), the science behind this legislative action is lacking. Controlled studies on its effectiveness and safety in use to cope with PTSD symptoms are needed to substantiate the perceived self-reported benefits of cannabis in this patient population and to test whether benefits of using plant-based cannabis outweigh the risks (Korem, Zer-Aviv, Ganon-Elazar, Abush, & Akirav, 2015). Findings from the present study provided further evidence that individuals with PTSD and MDD, the two most prevalent mental health disorders among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, are at increased risk for cannabis use and related problems including CUD. Future studies should consider examining other potential mediators that may also explain the link between PTSD and MDD with cannabis use (e.g., difficulty in emotion regulation; Bonn-Miller et al., 2011). Findings highlight the benefit of identifying specific motives for cannabis use, ones that are relevant to symptoms of PTSD and MDD such as sleep and coping with negative affect, as targets in empirically-supported treatments that can alleviate these symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a National Institute on Drug Abuse grant (R01 DA033425), awarded to Drs. Metrik and Borsari. Dr. Jackson's work on this project was supported by K02 AA13938. The funding sources had no other role other than financial support. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs. All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript and have all read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Cassandra Tardif, Rebecca Swagger, Madeline Benz, Hannah Wheeler, Suzanne Sales, and Julie Evon for their contribution to the project.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial relationship with the study sponsor, and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, Sellman JD. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agosti V, Nunes E, Levin F. Rates of psychiatric comorbidity among U.S. residents with lifetime cannabis dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:643–652. doi: 10.1081/ada-120015873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Babson KA, Ramo DE, Baldini L, Vandrey R, Bonn-Miller MO. Mobile app-delivered CBT for insomnia: Feasibility and initial efficacy among veterans with cannabis use disorders. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(3):e87. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3852. doi:10.2196/resprot.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol Rev. 2004;111(1):33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(1):75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Babson KA, Vujanovic AA, Short NA, Bonn-Miller MO. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use characteristics among military veterans with cannabis dependence. Am J Addict. 2013;22(3):277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.12018.x. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.12018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ. An evaluation of the nature of marijuana use and its motives among young adult active users. Am J Addict. 2009;18:409–416. doi: 10.3109/10550490903077705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Babson KA, Vandrey R. Using cannabis to help you sleep: Heightened frequency of medical cannabis use among those with PTSD. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014a;136:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Boden MT, Bucossi MM, Babson KA. Self-reported cannabis use characteristics, patterns and helpfulness among medical cannabis users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014b;40(1):23–30. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.821477. doi:10.3109/00952990.2013.821477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Harris AH, Trafton JA. Prevalence of cannabis use disorder diagnoses among veterans in 2002, 2008, and 2009. Psychol Serv. 2012;9(4):404–416. doi: 10.1037/a0027622. doi:10.1037/a0027622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Moos RH, Boden MT, Long WR, Kimerling R, Trafton JA. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on cannabis quit success. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(4):339–344. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1043209. doi:10.3109/00952990.2015.1043209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Boden MT, Gross JJ. Posttraumatic stress, difficulties in emotion regulation, and coping-oriented marijuana use. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40(1):34–44. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.525253. doi:10.1080/16506073.2010.525253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Drescher KD. Cannabis use among military veterans after residential treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(3):485–491. doi: 10.1037/a0021945. doi:10.1037/a0021945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Twohig MP, Medina JL, Huggins JL. Posttraumatic stress symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives: A test of the mediating role of non-judgmental acceptance within a trauma-exposed community sample. Mindfulness. 2010;1(2):98–106. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0013-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ. Emotional dysregulation: Association with coping-oriented marijuana use motives among current marijuana users. Subst Use Misuse. 2008b;43:1653–1665. doi: 10.1080/10826080802241292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Feldner MT, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Posttraumatic stress symptom severity predicts marijuana use coping motives among traumatic event-exposed marijuana users. J Trauma Stress. 2007a;20:577–586. doi: 10.1002/jts.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Marijuana use motives: Concurrent relations to frequency of past 30-day use and anxiety sensitivity among young adult marijuana smokers. Addict Behav. 2007b;32(1):49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.018. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky M, Bernstein A, Stickle T. Marijuana coping motives interact with marijuana use frequency to predict anxious arousal, panic-related catistrophic thinking, and worry in current marijuana users. Depress Anxiety. 2008a;25:862–873. doi: 10.1002/da.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Darnell A, Charney DS. Chronic PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans: Course of illness and substance abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(3):369–375. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller M, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt N. Marijuana use motives and social anxiety among marijuana-using young adults. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2238–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ. Cannabis and related impairment: the unique roles of cannabis use to cope with social anxiety and social avoidance. Am J Addict. 2014;23(6):598–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12150.x. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB, Carroll KM, Schatschneider C, Crapanzano K. Integrated CBT for cannabis use and anxiety disorders: Rationale and development. Addict Behav. 2014;39(3):495–496. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.023. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney A, Hughes J, Moore B, Vandrey R. Review of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1967–1977. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Moore BA, Rocha HL, Higgins ST. Clinical trial of abstinence-based vouchers and cognitive-behavioral therapy for cannabis dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(2):307–316. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.4.2.307. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.74.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski SJ, Galang JN, Short NA, Trafton JA, Gifford EV, Kimerling R, Bonn-Miller MO. Cannabis use disorder treatment barriers and facilitators among veterans with PTSD. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(1):73–81. doi: 10.1037/adb0000131. doi:10.1037/adb0000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski SJ, Norberg MM, Copeland J. The association between distress tolerance and cannabis use-related problems: The mediating and moderating roles of coping motives and gender. Addict Behav. 2012;37(10):1181–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.014. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Marijuana use and the risk of Major Depressive Episode. Epidemiological evidence from the US National Comorbidity Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(5):199–206. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0541-z. doi:10.1007/s00127-002-0541-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:18–24. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1117-3. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1117-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy DA, Arnedt JT. Sleep and substance use disorders: An update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):487. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0487-3. doi: 10,1007/s11920-014-0487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the NESARC. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ, Hawkins KA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use in a nationally representative sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(3):554–558. doi: 10.1037/a0023076. doi:10.1037/a0023076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Exploring the association between cannabis use and depression. Addiction. 2003;98(11):1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Funk R, Harrington Godley S, Godley MD, Waldron H. Cross-validation of the alcohol and cannabis use measures in the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) and Timeline Followback (TLFB; Form 90) among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Addiction. 2004;99(Suppl 2):120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of substance use disorders. 2009 Aug; Retrieved from http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/sud_full_601f.pdf.

- Earleywine M, Bolles JR. Marijuana, expectancies, and post-traumatic stress symptoms: A preliminary investigation. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46(3):171–177. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.920118. doi:10.1080/02791072.2014.920118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Metrik J, Bonn-Miller MO, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety sensitivity and distress intolerance in predicting cannabis dependence symptoms, problems, and craving: The mediating role of coping motives. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.889. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, Boden MT, Bonn-Miller MO. Cannabis use expectancies mediate the relation between depressive symptoms and cannabis use among cannabis-dependent veterans. J Addict Med. 2014;8:130–136. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000010. doi:10.1097/adm.0000000000000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold D, Fox J, Rehm J, Lev-Ran S. Natural outcome of cannabis use disorder: A 3-year longitudinal follow-up. Addiction. 2015;110(12):1963–1974. doi: 10.1111/add.13071. doi:10.1111/add.13071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. doi:0022-3956(75)90026-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton JJ, Calhoun PS, Wagner HR, Schry AR, Hair LP, Feeling N, Beckham JC. The prevalence of PTSD in OEF/OIF Veterans: A meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;31:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.02.003. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AN, Salloum IM. Polysomnographic sleep distrubances in nictoine, caffeine, alcohol, cocaine, opioid, and cannabis use: A focused review. Am J Addict. 2015;24(7):590–598. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12291. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates PJ, Albertella L, Copeland J. The effects of cannabinoid administration on sleep: A systematic review of human studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(6):477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.02.005. doi: 10,1016/j.smrv.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M, Suh JJ, Lynch KG, Szucs R, Ross J, Xie H, Oslin DW. Identifying risk factors for marijuana use among VA patients. J Addict Med. 2010;4(1):47–51. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181b18782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Vazan P, Bennett AS, Liberty HJ. Unmet need for treatment of substance use disorders and serious psychological distress among veterans: A nationwide analysis using the NSDUH. Mil Med. 2013;178(1):107–114. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DB, Chuo SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, Grant BF. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1235–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Jiang H, Campbell AN, Hu MC, Miele GM, Cohen LR, Nunes EV. Do treatment improvements in PTSD severity affect substance use outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial in NIDA's Clinical Trials Network. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(1):95–101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K, Mullin JL, Marshall EC, Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky M. Exploring the mediational role of coping motives for marijuana use in terms of the relation between anxiety sensitivity and marijuana dependence. The American Journal on Addictions. 2010;19(3):277–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00041.x. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K, Bonn-Miller M, Leyro T, Zvolensky M. Anxious arousal and anhedonic depression symptoms and frequency of current marijuana use: Testing the mediating role of marijuana coping motives among active users. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:543–550. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevorkian S, Bonn-Miller M, Belendiuk K, Carney D, Roberson-Nay R, Berenz E. Associations among trauma, PTSD, cannabis use, and CUD in a nationally representative epidemiologic sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(3):633–638. doi: 10.1037/adb0000110. doi:10.1037/adb0000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korem N, Zer-Aviv TM, Ganon-Elazar E, Abush H, Akirav I. Targeting the endocannabinoid system to treat anxiety-related disorders. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2015-0058. doi:10.1515/jbcpp-2015-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche LJ, De Koninck J. Sleep disturbance in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1257–1270. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie P, Katz N, Pillar G, Zinger Y. Elevated awaking thresholds during sleep: characteristics of chronic war-related posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(10):1060–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00037-7. doi:S0006-3223(98)00037-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Hendershot CS, Grossbard JR. Development and preliminary validation of a comprehensive marijuana motives questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:279–287. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. Erlbaum and Taylor Francis Group; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Metrik J, Kahler CW, McGeary JE, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ. Acute effects of marijuana smoking on negative and positive affect. J of Cog Psychotherapy. 2011;25:1–16. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.25.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell H, Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA. Incremental validity of coping-oriented marijuana use motives in the predicition of affect-based psychological vulnerability. J Psychopathol Behav. 2007;29:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Moitra E, Christopher PP, Anderson BJ, Stein MD. Coping-motivated marijuana use correlates with DSM-5 cannabis use disorder and psychological distress among emerging adults. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(3):627–632. doi: 10.1037/adb0000083. doi:10.1037/adb0000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein KL. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (1998-2004). Sleep. 2006;29(11):1398–1414. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Edition ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Finney JW, Moos RH. Two-year posttreatment functioning and coping of substance abuse patients with PTSD. Psychol Addict Behav. 1999;13:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Jungquist C, Smith MT, Posner D. CBT of insomnia: A session-by-session guide. Vol. 1. Springer Science & Business Media; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Nich C, Carroll KM. Primary outcomes in two randomized controlled trials of treatments for cannabis use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118(2-3):408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.021. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D, Haney M, Budney AJ, Piazza PV. Roundtable discussion: Legal or illegal, cannabis is still addictive. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2016;1(1):47–53. doi: 10.1089/can.2015.29004.rtd. Doi: 10.1089/can.2015.29004.rtd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter CM, Vujanovic AA, Marshall-Berenz EC, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO. Posttraumatic stress and marijuana use coping motives: the mediating role of distress tolerance. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(3):437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.007. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101(11):1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin ME, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Understanding comorbidity between PTSD and SUDs: two preliminary investigations. Addict Behav. 1995;20:643–655. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Gima K, Chu A, Marmar CR. Getting beyond “Don't ask; don't tell”: An evaluation of US Veterans Administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):714–720. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115519. doi:AJPH.2007.115519 [pii]10.2105/AJPH.2007.115519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Miner CR, Sen S, Marmar C. Bringing the war back home: Mental health disorders among 103,788 US veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at Department of Veterans Affairs facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):476–482. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.476. doi:167/5/476 [pii]10.1001/archinte.167.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L. Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001-2010: Implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116(1-3):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.027. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Metzler TJ, Gima KS, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Marmar CR. Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs health care, 2002-2008. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1651–1658. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150284. doi:AJPH.2008.150284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(3):326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. doi:10.1037/0893-164x.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Conrod PJ. Functional associations among trauma, PTSD, and substance-related disorders. Addict Behav. 1998;23:797–812. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey R, Babson KA, Herrmann ES, Bonn-Miller MO. Interactions between disordered sleep, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(2):237–247. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.901300. doi:10.3109/09540261.2014.901300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Burnam A, Kung FY, Paddock S. A national survey of care for persons with cooccurring mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1062–1068. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O'Hara MW, Simms LJ, Kotov R, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez EA, Stuart S. Development and validation of the inventory of depression and anxiety symptoms. Psych Assessment. 2007;19:253–268. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-administered PTSD scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13(3):132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward SH, Arsenault NJ, Murray C, Bliwise DL. Laboratory sleep correlates of nightmare complaint in PTSD inpatients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(11):1081–1087. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00917-3. doi:S0006-3223(00)00917-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Johnson K, Hogan J, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO. Relations between anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and fear reactivity to bodily sensations to coping and conformity marijuana use motives among young adult marijuana users. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;17(1):31–42. doi: 10.1037/a0014961. doi:10.1037/a0014961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]