Abstract

Hexafluorobenzene (HFB) reacts with free thiols to produce a unique and selective perfluoroaromatic linkage between two sulfurs. We modified this chemical reaction to produce dimeric 18F-RGD-tetrafluor-obenzene (TFB)-RGD, an integrin αvβ3 receptor ligand. 18F-HFB was prepared by a fluorine exchange reaction using K18F/K2.2.2 at room temperature. The automated radiofluorination was optimized to minimize the amount of HFB precursor and, thus, maximize the specific activity. 18F-HFB was isolated by distillation and subsequently reacted with thiolated c(RGDfk) peptide under basic and reducing conditions. The resulting 18F-RGD-TFB-RGD demonstrated integrin receptor specific binding, cellular uptake, and in vivo tumor accumulation.18F-HFB can be efficiently incorporated into thiol-containing peptides at room temperature to provide novel imaging agents.

Graphical abstract

Developing simple synthetic approaches for 18F-labeling has been the thrust of research in many laboratories.1 Although there are many different concepts of “simple”, one criterion is the incorporation of 18F-fluoride in the final radiosynthetic step. Nucleophilic substitution reactions with 18F-fluoride ion are typically conducted under basic conditions at elevated temperatures. Consequently, many biomolecules may undergo hydrolytic reactions that result in disruption of their biological activity. Because of this, 18F-labeling of biomolecules is often accomplished through the use of 18F-labeled prosthetic groups. Prosthetic radiolabeling requires several steps including preparation and purification of the 18F-prosthetic group by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) before conjugation, under mild conditions, to the biomolecules.1,2 Numerous 18F-prosthetic groups have been developed for conjugation by chemical reaction at amine- or thiol-functional groups inherent in the biomolecules or small drug-like molecules via acylation, alkylation, amidation, imidation, oxime, or hydrazone formation.3–6 An additional class of prosthetic groups containing functional groups operative in click-reactions has also been developed for reaction with properly functionalized substrates.7,8

Recently, Pentelute and co-workers reported the usage of hexafluorobenzene (HFB) in peptide/small protein stapling.9 HFB was reacted with free thiols, exclusively by 1,4-disubstitution, to produce a unique and selective perfluoroaromatic linkage between the sulfurs.9,10 We examined two radiolabeling approaches that utilize this method: (1) nucleophilic radiofluorination on the tetrafluoroaromatic linker, and (2) preparation of 18F-HFB and subsequent reaction of thiol containing molecules to simultaneously radiolabel and dimerize.

HFB is chemically inert and highly stable under conditions such as radiation and heat. The strongly electronegative fluorine atoms deactivate the aromatic ring, making it highly susceptible to nucleophilic substitution. Direct displacement of a fluorine anion in HFB is feasible by the usage of strong nucleophilic reagents and the formation of transition metal complexes.11,12 Substitution of one or more fluorine atoms in HFB took place via reactions with hydroxides, alkoxides, aqueous amines, and organolithium reagents.11,12 Sequential displacement of two fluorine atoms predominantly provides para substitution.

Herein we conducted the direct radiofluorination of a para-substituted tetrafluorobenzene. Because the direct nucleophilic exchange conditions were viewed as too harsh for biomolecules, we exploited the second approach. As a proof-of-concept, we demonstrated the dimerization of two thiolated RGD peptides by reaction with 18F-HFB.

We prepared a tetrafluorophenyl dimer and subsequently conducted a fluoride exchange reaction. The dimer was synthesized by reaction of HFB with 2 equiv of 4-chlorobenzenemethanethiol to give tetrafluoro-(1,4-phenylene)bis((4-chlorobenzyl)sulfane (Ph-S-TFB-S-Ph) in 45% yield (Figure 1A). Successful exchange labeling of one of the four aromatic fluorines on Ph-S-TFB-S-Ph (7–31 μmol) was achieved using 1.5 equiv of tetrabuthylammonium bicarbonate and 8–10 mCi of F-18, providing a 33% radiochemical yield (Figure 1B). This direct labeling method required a reaction temperature of 90 °C for 15 min. Although this method may be applicable for heat-stable small molecules, we deemed these conditions unsuitable for general peptide labeling. We did not exhaustively investigate but directed our attention to the second approach that allows thiol containing molecules to react with 18F-HFB for simultaneous radiolabeling and dimerization.

Figure 1.

(A) Radiosynthesis of 18F-Ph-S-TFB-S-Ph from 18F-HFB. (B) Representative radioTLC of 18F-Ph-S-TFB-S-Ph crude reaction using normal phase TLC plates and 20% methanol in dichloromethane as a developing solvent.

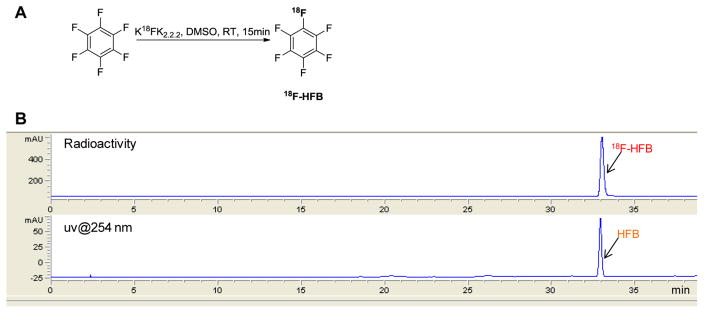

The published radiosynthesis of 18F-HFB (Figure 2)13 was adapted for automation on a modular system (Eckert and Ziegler). The synthesis was conducted at room temperature (RT) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and quantities of K2CO3, K2.2.2, and HFB were adjusted in order to achieve good yields using the lowest amount of HFB (Table 1). 18F-HFB was isolated by distillation with argon flow at 25 °C into a vial containing dimethylformamide (DMF) cooled in dry ice/acetonitrile (−45 °C). Radiochemical yields (RCY) were calculated based on collected 18F-HFB divided by initial 18F activity (Table 1). The optimized conditions, using only 500 μg (2.7 μmol) of HFB, provided a 25 ± 3% isolated RCY (n = 6, non-decay-corrected) with specific activity (SA) of 50 mCi/μmol.

Figure 2.

(A) Radiosynthesis route of 18F-HFB. (B) Representative HPLC radioactive (upper) and UV (lower) chromatograms of isolated 18F-HFB.

Table 1.

Different Reaction Conditions of Automatic Labeling 18F-HFB in an Eckert and Ziegler Modulea

| K2CO3 | K2.2.2 | HFB | isolated yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.83 mg (6 μmol) | 4.5 mg (12 μmol) | 7 mg (37 μmol) | 28 |

| 0.17 mg (1.2 μmol) | 0.9 mg (2.4 μmol) | 1.4 mg (7.5 μmol) | 15 |

| 0.03 mg (0.24 μmol) | 0.18 mg (0.48 μmol) | 0.24 mg (1.3 μmol) | 0 |

| 0.83 mg (6 μmol) | 4.5 mg (12 μmol) | 1.4 mg (7.5 μmol) | 25 |

| 0.83 mg (6 μmol) | 4.5 mg (12 μmol) | 0.7 mg (3.8 μmol) | 25 |

| 0.83 mg (6 μmol) | 4.5 mg (12 μmol) | 0.5 mg (2.7 μmol) | 25 |

| 0.83 mg (6 μmol) | 4.5 mg (12 μmol) | 0.35 mg (1.9 μmol) | 15 |

| 0.83 mg (6 μmol) | 4.5 mg (12 μmol) | 0.2 mg (1 μmol) | 0 |

Isolated yield was calculated from F-18 activity at the start of synthesis to the isolated product after distillation.

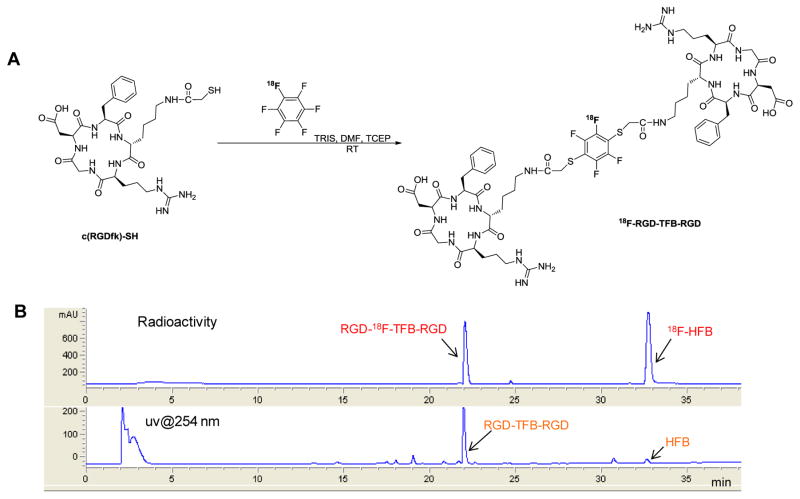

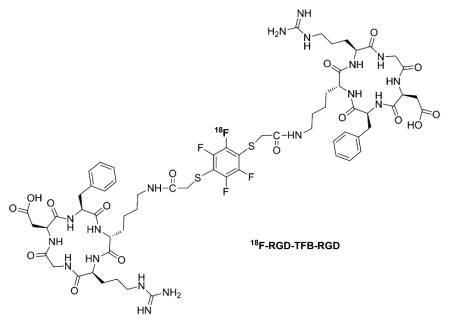

For the dimerization reaction, an aliquot of the product containing 1 equiv of 18F-HFB (5–10 mCi, 0.1–0.2 μmol) was reacted with 2 equiv of thiolated c(RGDfK) peptide (0.44–0.73 μmol), excess amount of TRIS base (24 equiv), and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP, 2.5 equiv), a reducing agent, at RT in DMF. After reaction for 20–25 min, there was about 50% conversion, based on HPLC, into the desired dimerized product, RGD-18F-TFB-RGD (Figure 3). The product was isolated in 40 ± 2% radiochemical yield (n = 4) with SA of 15 mCi/μmol. During the dimerization reaction, each thiol attack increases the probability that the radioactive fluorine atom will be displaced from HFB. Attempts to conduct this reaction without TCEP resulted in a higher amount of undesired disulfide dimer, presumably from oxidative coupling (Supporting Information Figure S1). The structure was confirmed by comparison of HPLC profile to that of authentic standard characterized by LC-MS analysis (Supporting Information Figure S2).

Figure 3.

(A) Radiosynthesis of 18F-RGD-TFB-RGD from 18F-HFB. (B) Representative HPLC chromatogram (radioactivity, upper; and UV, lower) of crude aliquot from the labeling of 18F-RGD-TFB-RGD.

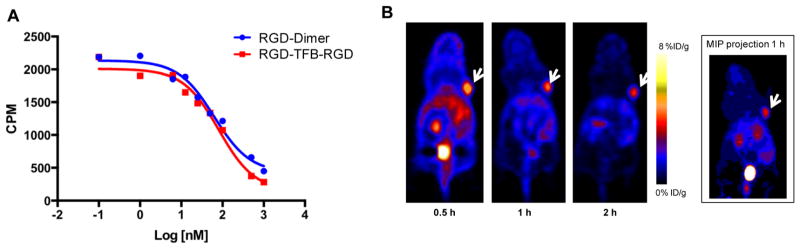

Biologically, introduction of HFB group into thiolated c(RGDfk) peptide provided a dimer that displayed a similar IC50 value in αvβ3 expressing U87MG cells compared to the known dimer E[c(RGDfK)]2 (81 nM vs 62 nM, Figure 4A). Furthermore, PET imaging, following intravenous injection of RGD-18F-TFB-RGD (10–20 nmol injected mass dose) to a U87MG xenograft model, showed good tumor uptake (~4% ID/g at 1 h postinjection) and high tumor-to-background contrast (tumor/muscle = 9.8, Figure 4B). This tumor uptake was comparable to dimeric RGD peptides radiolabeled by other 18F-synthons, such as N-succinimidyl 4-18F-fluorobenzoate (18F-SFB). RGD-dimer conjugated to 18F-SFB was reported to have tumor uptake of 3.8 ± 0.8%ID/g at 70 min post-injection.14 No significant defluorination was observed up to 2 h post-injection (Table 2). The specificity of RGD-18F-TFB-RGD was confirmed by blocking studies (Supporting Information Figure S3). Excess amount of c(RGDfk) peptide significantly blocked RGD-18F-TFB-RGD uptake in the tumor (Supporting Information Figure S3).

Figure 4.

(A) Competition cell binding assay of RGD-TFB-RGD and RGDfk-dimer against 125I-echistation in U87MG αvβ3 expressing cells. The results are shown as average of triplicates ± standard deviation. (B) Representative coronal PET images of mouse bearing U87MG tumor (marked with white arrows) at 0.5, 1, and 2 h post-injection of 18F-RGD-TFB-RGD and MIP projection image of the same mouse at 1 h post-injection.

Table 2.

Biodistribution of RGD-18F-TFB-RGD in Normal Mice at 0.5 and 2 h Post-Injection (%ID/g)a

| 0.5 h

|

2 h

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | STD | Average | STD | |

| Heart | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| Lung | 1.08 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.04 |

| Liver | 0.74 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.06 |

| Spleen | 0.53 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.05 |

| Stomach | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0.09 |

| Intestine | 0.73 | 0.20 | 0.57 | 0.19 |

| Kidneys | 1.84 | 0.57 | 1.04 | 0.16 |

| Muscle | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Bone | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.01 |

| Blood | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

Results are shown as average of 4 mice ± STD.

In general, radiochemical syntheses are conducted to obtain the highest possible specific activity. Most biological targets of interest for biomedical imaging have limited numbers per cell and their successful imaging requires high affinity ligands with high specific activity.15 The tracer principle also requires a low occupancy of receptors to avoid physiological perturbation. However, in some cases the biological target can still be imaged at somewhat lower specific activity. In a human study of somatostatin receptor imaging, the high specific activity tracer was trapped by the off-target binding; optimal images were obtained by pre-injection of a small amount of unlabeled peptide prior to injection of radiotracer.15 We observed a similar phenomenon when studying high specific activity 18F-SFB labeled T140 peptide. This peptide showed undesired binding to off-target sites on red blood cells that inhibited the specific binding to CXCR4 positive tumor. The ability to image the tumor was overcome by lowering the SA through addition of a small amount of unlabeled T140 peptide.16 Another example reported in the literature for antibodies or macromolecules suggested that highest specific activity was not optimal, because a low amount of tracer might be removed rapidly from the circulation and result in low uptake in tumors.17 Thus, the specific activity of a molecular imaging tracer needs to be appropriate for its application, not necessarily as high as possible.17 Our approach of 18F-labeling via 19F–18F exchange reaction with moderately high specific activity would be suitable for certain biological applications where the cell receptor density is high and/or the target binding is highly sensitive to the amount of radioligand administered.

To analyze the specificity of HFB displacement reaction toward free thiols rather than free amines that are present on lysine residues, HFB was reacted with T140, a small peptide that has two Cys, one L-Lys, and one D-Lys (Supporting Information Figure S4). Excess of HFB (2.5–25 equiv) was reacted with reduced T140 peptide for several hours to give the corresponding cyclic product T140-TFB (Supporting Information Figure S4). The major byproduct of this reaction was the formation of cyclic T140 peptide with disulfide bond as determined by LC-MS (Supporting Information Figure S5). Similarly, when the reduced T140 was reacted with 18F-HFB there was only 8–13% conversion by HPLC (Supporting Information Figure S6). Attempts to add TCEP in order to prevent disulfide bond, as was done for the RGD dimer, did not increase the yield, perhaps because the formation of the disulfide bond by the T140 Cys groups is an intramolecular and not intermolecular manner. It is important to emphasize that we could not detect any byproduct in which the 18F-HFB reacted with the amine of the Lys.

Other methods of 18F incorporation employed in the final radiochemical step, such as formation of SiFA, BF3, and AlF,18–24 have been reported. BF3 and AlF methods are conducted under acidic conditions, with or without heating. Our approach presented in this paper is a complementary method that allows the unique formation of cyclic and dimeric products using mildly basic conditions at room temperature. As such, it provides uniquely radiolabeled products not easily attainable by any reported method.

In conclusion, we reported a novel prosthetic group for labeling and dimerizing both peptides and small molecules. This reaction, which can be conducted either in one step under heating condition or in two steps at room temperature, provides a unique method for preparing radiolabeled dimeric biomolecules.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Experimental section. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00278.

References

- 1.Jacobson O, Kiesewetter DO, Chen X. Fluorine-18 radiochemistry, labeling strategies and synthetic routes. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015;26:1–18. doi: 10.1021/bc500475e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiesewetter DO, Jacobson O, Lang L, Chen X. Automated radiochemical synthesis of [18F]FBEM: a thiol reactive synthon for radiofluorination of peptides and proteins. Appl Radiat Isot. 2011;69:410–4. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes-Seeman D, Beck J, Springer C. Fluorinated compounds in medicinal chemistry: recent applications, synthetic advances and matched-pair analyses. Curr Top Med Chem. 2014;14:855–64. doi: 10.2174/1568026614666140202204242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollingworth C, Gouverneur V. Transition metal catalysis and nucleophilic fluorination. Chem Commun (Cambridge) 2012;48:2929–42. doi: 10.1039/c2cc16158c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pretze M, Grosse-Gehling P, Mamat C. Cross-coupling reactions as valuable tool for the preparation of PET radiotracers. Molecules. 2011;16:1129–65. doi: 10.3390/molecules16021129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coenen HH. Fluorine-18 labeling methods: Features and possibilities of basic reactions. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. 2007:15–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-49527-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng D, Zeglis BM, Lewis JS, Anderson CJ. The growing impact of bioorthogonal click chemistry on the development of radiopharmaceuticals. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:829–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.115550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horisawa K. Specific and quantitative labeling of biomolecules using click chemistry. Front Physiol. 2014;5:457. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spokoyny AM, Zou Y, Ling JJ, Yu H, Lin YS, Pentelute BL. A perfluoroaryl-cysteine S(N)Ar chemistry approach to unprotected peptide stapling. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:5946–9. doi: 10.1021/ja400119t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arisawa M, Suzuki T, Ishikawa T, Yamaguchi M. Rhodium-catalyzed substitution reaction of aryl fluorides with disulfides: p-orientation in the polyarylthiolation of polyfluorobenzenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12214–5. doi: 10.1021/ja8049996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonucci JM, Wall LA. High-temperature reactions of hexafluorobenzene. J Res Natl Bur Stand. 1966;70A:473–480. doi: 10.6028/jres.070A.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wall LA, Pummer WJ, Feam JE, Antonucci JM. Reactions of polyfluorobenzenes with nucleophilic reagentsl. J Res Natl Bur Stand. 1963;67A:481–497. doi: 10.6028/jres.067A.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blom E, Karimi F, Långström B. [18F]/19F exchange in fluorine containing compounds for potential use in 18F-labelling strategies. J Labelled Compound Radiopharm. 2009;52:504–511. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Xiong Z, Wu Y, Cai W, Tseng JR, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Quantitative PET imaging of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression with 18F-FRGD2. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:113–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velikyan I, Sundin A, Eriksson B, Lundqvist H, Sorensen J, Bergstrom M, Langstrom B. In vivo binding of [68Ga]-DOTATOC to somatostatin receptors in neuroendocrine tumours–impact of peptide mass. Nucl Med Biol. 2010;37:265–75. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson O, Weiss ID, Kiesewetter DO, Farber JM, Chen X. PET of tumor CXCR4 expression with 4-18F-T140. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1796–804. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandit-Taskar N, O’Donoghue JA, Morris MJ, Wills EA, Schwartz LH, Gonen M, Scher HI, Larson SM, Divgi CR. Antibody mass escalation study in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer using 111In-J591: lesion detectability and dosimetric projections for 90Y radioimmunotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1066–74. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.049502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schirrmacher R, Bradtmoller G, Schirrmacher E, Thews O, Tillmanns J, Siessmeier T, Buchholz HG, Bartenstein P, Wangler B, Niemeyer CM, Jurkschat K. 18F-labeling of peptides by means of an organosilicon-based fluoride acceptor. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:6047–50. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wangler B, Quandt G, Iovkova L, Schirrmacher E, Wangler C, Boening G, Hacker M, Schmoeckel M, Jurkschat K, Bartenstein P, Schirrmacher R. Kit-like 18F-labeling of proteins: synthesis of 4-(di-tert-butyl[18F]fluorosilyl)benzenethiol (Si[18F]FA-SH) labeled rat serum albumin for blood pool imaging with PET. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:317–21. doi: 10.1021/bc800413g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Liu Z, Lozada J, Wong MQ, Lin KS, Yapp D, Perrin DM. Single step 18F-labeling of dimeric cycloRGD for functional PET imaging of tumors in mice. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40:959–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Li Y, Lozada J, Schaffer P, Adam MJ, Ruth TJ, Perrin DM. Stoichiometric leverage: rapid 18F-aryltrifluoroborate radiosynthesis at high specific activity for click conjugation. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:2303–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wan W, Guo N, Pan D, Yu C, Weng Y, Luo S, Ding H, Xu Y, Wang L, Lang L, Xie Q, Yang M, Chen X. First experience of 18F-alfatide in lung cancer patients using a new lyophilized kit for rapid radiofluorination. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:691–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.113563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Souza CA, McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Todaro LJ, Goldenberg DM. High-yielding aqueous 18F-labeling of peptides via Al18F chelation. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:1793–803. doi: 10.1021/bc200175c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo J, Lang L, Hu S, Guo N, Zhu L, Sun Z, Ma Y, Kiesewetter DO, Niu G, Xie Q, Chen X. Comparison of three dimeric 18F-AlF-NOTA-RGD tracers. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16:274–83. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0668-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.