Abstract

Liver cirrhosis is a public health problem and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is one of its main complications, which can be either overt meaning thereby evident and readily diagnosed, or covert/minimal (CHE) needing psychometric testing for diagnosis. Patients with CHE hepatic encephalopathy have deficits in multiple domains including visuo-spatial assessment, attention, response inhibition, working memory, along with psychomotor speed to name a few areas. These patients have poor navigational skills, get fatigued easily and demonstrate poor insight into their driving deficits. The combination of all these leads them to have poor driving skills leading to traffic violations and crashes as demonstrated not only on the simulation testing but also in real life driving events. There are multiple psychometric tests for CHE testing but these are not easily available and there is no uniform consensus on the gold standard testing as of yet. It does not automatically connote that all patients who test positive on driving simulation testing are unfit to drive. The physicians are encouraged to take driving history from the patient and the care- givers on every encounter and focus their counseling efforts more on patients with recent history of traffic crashes, with abnormal simulation studies and history of alcohol cessation within last year. As physicians are not trained to determine fitness to drive, their approach towards CHE patients in regards to driving restrictions should be driven by ethical principles while as respecting the local laws.

Keywords: CHE, Driving, Motor vehicle crashes, Public health problem, EncephalApp Stroop Test

Liver cirrhosis with prevalence as high as 0.27% in the population is an important health care issue in the United States (US)[1]. This translates to nearly 633,323 US adults being affected at any time with liver cirrhosis and around 70% of these not aware of their disease process[1]. No doubt, it is the eighth leading cause of death in the US[1, 2]. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a serious complication of cirrhosis and its relative contribution to the utilization of resources is rapidly growing[3, 4]. The definition according to the recently published American Association For The Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines is that HE is “a brain dysfunction caused by liver insufficiency and/or portosystemic shunting (PSS); it manifests as a wide spectrum of neurological or psychiatric abnormalities ranging from subclinical alterations to coma”[5]. HE may not always be simple to diagnose. Cases that are mild with no obvious clinical profile may be diagnosed by using neuropsychometric testing and are classified as covert hepatic encephalopathy (CHE). The previous terminology for CHE included minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) where there is no clinical sign, cognitive or other of HE or subclinical HE. On the other hand, overt HE (OHE) is readily identifiable to the clinician and does not need specific neuropsychometric testing. In the spectrum of Neuro-cognitive Impairment in Cirrhosis (SONIC), CHE includes minimal and Grade I HE, and OHE encompass Grades II-IV HE of the WHC[6, 7]. For the remainder of this review we will use the terms MHE and CHE interchangeably. The rate of CHE in the United States ranges from 30–60%[8, 9]. There is now an understanding that patients with CHE have a higher likelihood of eventually developing OHE[8, 10–12].

Research in the field of CHE has linked it to be related to poor driving outcomes in addition to affecting other domains of the patient’s life. These issues with daily function include a poor health-related quality of life, impact on socio-economic status and a higher incidence of falls[13, 14]. Hence, given the absolute number of cirrhotic patients with CHE this article examines the question pertaining to the safety of driving an automobile in these patients. Driving is an important aspect of daily function and it often determines employability and self-sufficiency in instrumental activities of daily living. Currently, there are no specific guidelines about whether patients laboring under the influence of CHE can drive safely or not. However the available evidence will be reviewed below.

What does normal driving entail?

For safe execution of driving three elements have been recognized to be the most important and these are vision, cognition and motor functions [15]. With the decisions about driving being made on a “tactical, strategic and an operational level” [16]. Good visual perception, in simplistic terms allows a driver to survey the road, see the obstacles, read the directions, the color signals signs in the front, the lane change and other signals from the co-drivers and so on. Visual problems (diminished visual acuity, poor depth perception, poor peripheral vision, poor contrast/visual field sensitivity, poor color vision) have been potentially associated with many poor driving outcomes [17, 18]. Intact cognition allows the driver to formulate driving plans based on road conditions drawing from previous memorized driving experiences. This will culminate in successfully navigating the environments and modulating the speeds within the permissible limits as per local laws. Intact psychomotor capabilities enable appropriate actions like steering, applying brake, coordinating brake and clutches, turning, passing, acceleration and deceleration. Above all, at all times drivers should maintain un-divided attention on the road and minimize distractions like texting and using phones which have been associated with worse traffic outcomes[19]. Various disease states and conditions like Alzhiemer’s disease, Parkinson’s, Obstructive sleep apnea, old age to name a few have been shown to be linked to poor driving outcomes by increasing errors from impairment in attention, perception, response selection, motor functions and in level of sleepiness [20–22]. With aging there occurs gradual decline in faculties such as physical, sensory and cognitive functions[23]. However, chronological age in itself may not be the cause of increased crash rates in the elderly and this may be secondary to multiple medical problems and polypharmacy secondary to aging[24]. And to add to the problem people in this age group are susceptible to poor quality of life and depressive illness when they stop driving[25]. Adequate auditory inputs allow the driver to listen to other approaching co- drivers, stay in tune to the sound of their own vehicles and listen to horn sounds from the other automobiles on the road. In short, the safe and successful driving of an automobile which is a complex exercise requires involvement of multiple senses and faculties sequentially or all at once for coordination of different actions for completion of task. Driving remains a privilege and not a right in most jurisdictions.

What are the Societal Ramifications for driving?

According to the November, 2015 report published by the U.S. Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) www.nhtsa.gov as regards to the crash data for the year 2014: there have been 32,675 mortalities with 2.3 million injuries and 6.1 million police reported crashes during the same time. In this data, alcohol related fatalities, distracted driving, and drowsiness related causes were reported as 31%, 10% and 2.6% respectively[26]. When a critical analysis of the reasons for crashes using a survey method was done by the NHSTA for the year 2005–2007 using a weighted sample (total crashes 2,189,000 crashes in the country): It was found that the critical reason (which is the last event in the crash cause) was assigned to the driver in around 94 percent cases. The recognition error, decision error, performance error, non-performance error were the top four reasons accounting for 41%, 33%, 11% and 7% respectively[27]. However, as per the report generated for the first six months of 2015 by the National Safety Council the motor vehicles deaths have been put at 18,630 which is nearly 14% increase from the same time period in 2014, which has translated in an increase of 24% ($150.0 billion) from year 2014[28]. This has been related to the low gas prices leading to increased driving. As noted above, the main reason for automobile crashes is mostly human error and costs the society both in terms of money and blood. States are expected to keep a watch, detect and prevent drivers who can potentially be harmful to themselves and others from driving. At the one end of the spectrum are the young and the inexperienced drivers who have to drive under certain restrictions till they are gaining more experience while as at the other end are the ever-growing older populations with the issues related to diseases and age. Society has to balance the need for both and to ensure there are robust mechanisms available in the form or laws and legislations available to restrict impaired drivers, which unfortunately may not be the case at this time. This takes more importance in case of patients with cirrhosis who have much poorer outcomes after motor vehicle crashes as demonstrated by Bajaj et al. (2008), study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2004 concluded “cirrhosis is associated with greater mortality, length of stay and charges after motor vehicle crash despite controlling for injury severity, comorbidities, and age in NIS 2004[29].”

What goes wrong with driving in CHE: fatigue, navigational skills impairment and lack of insight?

Gitlin et al. (1986) reported that in a group of well compensated cirrhotics without OHE nearly 70% had subclinical HE using psychometric test and raised the concerns about “impairment of performance rather than verbal skills” in such patients and drew our attention to the fact about limitations such patients could face in skilled and or in mechanical occupations[30]. In more recent studies, the prevalence of CHE has been found to be as high as 84% in tested patients[31, 32]. Further, since then on with the recognition that CHE is an important global problem further research has allowed us to gain more insight into its pathophysiology, clinical course, prognosis and outcome.

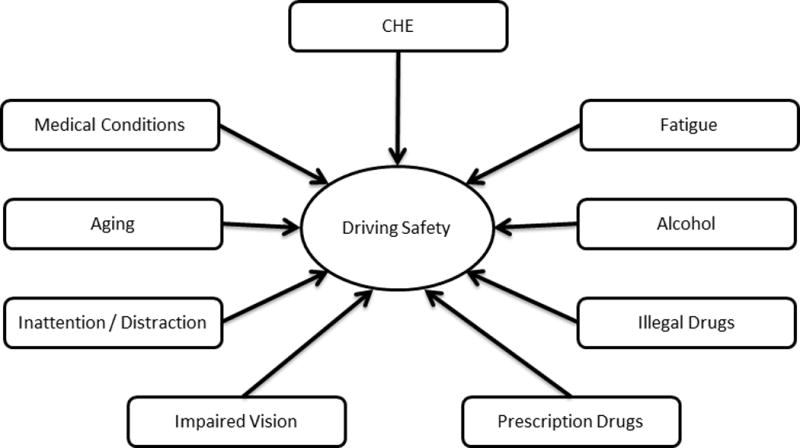

Patients with CHE have defects in visuo-spatial assessment, impaired attention, response inhibition and working memory, impaired speed of information processing and impaired psychomotor speed as well[32, 33]. All of these deficits culminate in poorer driving skills in patients with CHE in real world driving results as demonstrated by Bajaj et al. [34]. The same group had earlier demonstrated that impaired navigational skills add another level of difficulty for patients with CHE[35]. Fatigue has been related to driving difficulties in both CHE and OHE and predicts collisions[36]. Along with the fact that in CHE there seems to be impairment of driving decisions at tactical level (passing) and operational levels (braking and steering wheel handling)[37]. In patients with CHE, the driving experience or skills prior to diagnosis of CHE may also influence the driving skills after diagnosis[38]. Therefore, in addition to above causes multiple other factors can influence the driving skills in CHE patients (Fig. 1)[39]. This leads us to question the assumption that patients who test positive for CHE should automatically not drive as they are dangerous drivers[40]. As they may be laboring under other contributory causes which should be painstakingly sought and addressed if possible.

Figure 1.

Many factors affect driving skills in patients with cirrhosis, not just minimal hepatic encephalopathy.

(Modified and reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons Ltd, Lauridsen MM, Wade, James B, Bajaj, Jasmohan S. What is the Ethical (Not Legal) Responsibility of a Physician to Treat Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Advise Patients Not to Drive? Clinical Liver Disease. 2015;6:86–89).

Patients with CHE have deficits at multiple levels or in multiple areas leading to many difficulties including in driving. Good navigation, which is a complex system requiring working memory (WM) and other domains affected by CHE are needed for safe driving especially in unfamiliar surroundings and challenging circumstances[41]. WM helps in successfully executing daily tasks by short term recall of newer memory or retrieved memory sets and by helping formulating correct rapid response while adapting to new situations drawing from pervious learned short term experiences[42].

Driving issues in CHE have been studied at three different levels

Simulator performance

On-road driving performance with a driving instructor

Analysis of traffic offenses

Simulator studies

Bajaj et al. (2008) aimed at determining the effects of MHE on navigational skills with correlations with psychometric testing concluded, “ patients with MHE have impaired complex navigational skills on a driving simulator, and this correlates with impairment in response inhibition and attention[35].” In this study, 49 non- alcoholic cirrhotics (34 MHE+ and 15 MHE−) and 48 age and education matched controls were studied using Psychometric testing battery, Inhibitory control test (ICT) and simulation for driving. Navigation in particularly, was studied by using a simulator’s “virtual city” and assessed driving along a marked path on the map with the outcome being the illegal turns. Both illegal turns and accidents were higher in the MHE+ as compared to MHE− and controls. The ICT impairments (measuring response inhibition) were correlated with both illegal turns and accidents. Hence, the conclusions as noted above[35]. Impaired response inhibition (as detected by ICT/illegal turns) is known to be associated with MHE and causes alteration of executive control[35, 43]. The above study supports the results of earlier smaller study by Nyberg et al. in a larger cohort of well controlled, non- alcoholic subjects about navigation skills in MHE[44].

Previously it was known that along with other deficits patients with OHE have associated fatigue[45]. The presence of fatigue is associated with driving difficulties in healthy individuals and in conditions like attention deficit disorder (ADD), which can be likened to deficits similar to CHE patients[46–48]. Bajaj et al. (2009) were able to demonstrate that “over time, fatigue led to worsening of driving performance in patients with MHE; and both simulator collisions are predicated by development of actual driving associated fatigue in both OHE and MHE[36].” In this study, a driving simulation was done for assessing effect of fatigue on driving skills in cirrhotics (with recent OHE, MHE and no MHE) and age/education matched controls: the first half of driving skills were compared with second half. The American Medical Association (AMA) driver survey was the tool used to assess the driving-associated fatigue. It was found that in MHE and OHE patients vs. no MHE significantly higher proportions complained of fatigue after actual driving and all fatigued drivers as compared to non-fatigued had collisions on driving simulation. However, in the second half only MHE patents had a significant increase in the collisions, speeding and center crossings. This led to the conclusion being made that fatigue leads to worsening of simulator performance over time in MHE patients[36]. In comparison to healthy individuals, patients with MHE and OHE are prone to develop fatigue within a shorter period of time during driving, which is a high-intensity activity; this adds on to the underlying deficits in sustained attention and executive functions lead to poorer driving performances[36].

Patients with MHE have subtle signs and symptoms and hence may lack insight or self- awareness into their own poor driving skills and thus may not seek crucial intervention at the right time. Bajaj et al. (2008) investigated this very same idea, using a 26-item scale know as Driving Behavior Survey (DBS) which been validated by Barkley et al. for use in children and adults with ADD[49]; and used here as patients with MHE as well as ADD suffer from attention deficit. In this study, 47 non-alcoholic cirrhotic (36 MHE+, 11 MHE−) and 40 controls were studied with psychometric tests, DBS and driving simulation. A separate DBS was completed by an adult observer who being familiar with the patients driving skills[50]. The patients with MHE rated themselves equivalent to controls and MHE−, despite significantly worse performance on the simulation driving tests. Patient’s observers also rated the MHE+ patients as poorer drivers as compared to MHE− patients and or controls[50]. The author’s concluded, “MHE patients have poor insight into their driving skills. A part of MHE patient’s clinical interview should be to increase awareness of this driving impairment.”[50]

Lack of or poor insight into one’s disease process can have very deep implications for the patient’s. Drawing from the trans-theoretical model, CHE patients with driving problems may be in the “pre-contemplation stage” where-in they are unwilling to recognize a problem either by being unaware of the problem or by the belief held by the patients that they will be unable to change their behavior[51]. Anosognosia is a term named by famous neurologist Joseph Babinski in 1914 used to describe as a “deficit of self-awareness.” In Alzheimer’s disease as in other neuro-psychiatric illnesses, there is this same diminished sensory and cognitive awareness, which has been associated with dangerous behaviors and poor prognosis[52–54]. CHE patients are not aware of their driving impairment as they lack insight about this area. In view of the above discussion, Bajaj et al. suggest that CHE patients also suffer from poor insight into their driving skills[50]. A study by Montiliu et al. found that systemic inflammatory changes were related to poor simulator performance [55].

On-Road driving tests with instructors

In patients with MHE using psychometric testing the inability to drive safely has put between 15 and 75%[56, 57]. The earliest study showing that MHE had impact on driving abilities was done by a German group Schomerus et al. dating back to 1980’s[56]. In this study, 40 patients with liver cirrhosis but not in OHE were studied using psychometric testing and 60% were considered to be unfit for driving; all the ten patients with minimal EEG changes were considered unfit for driving[56]. After a period of decade or so, a small case control pilot study was done by Srivastava et al. from Chicago[58]. In this study, fifteen patients with cirrhosis (10 patients with MHE) had neuropsychological testing, laboratory driving test and a real road driving and it was concluded that there was no differences in the two groups[58]. At around the same time, Watanabe et al. from Japan did a small case control study consisting of sixteen compensated cirrhotics using the neuropsychological tests (reaction times) and found out that 44% were unfit to drive[59]. After these conflicting results, nearly after a lull of a decade or so in 2004 results from a larger prospective controlled study by Wein et al. from Germany came out[37]. In this study 48 cirrhotic patients out of which 14 having MHE (using three psychometric tests) vs. 49 non cirrhotic controls were studied using a standardized on-road driving test (90 minutes) conducted by a blinded professional driving instructor showed that the patients with MHE had a lowered total driving score as compared to controls and even other cirrhotics without MHE with three categories showing significant differences in such ratings as: car handling, adaptation and cautiousness with the instructor, in order to prevent accident having to intervene in 5 out of 14 MHE patients[37]. Thus it appears that CHE seems to impair driving and not cirrhosis per se. As the results of this larger study were different as compared to older studies this paved the way for further research in this area.

Actual driving offenses

Kircheis et al. (2009) published the results of a case control study (51/48 patients), in which psychometric testing, self assessment, real life driving in a specially equipped car and assessment by driving instructor was done[60]. In this study, 27 had MHE and 14 patients had G1HE (both of these come under CHE according to the latest guidelines); both MHE and Gr I HE patients showed significantly more violations of “in-lane keeping, reduced brake use, prolonged reaction times, and diminished stress tolerance” as compared with controls or ten cirrhotic patients in the group. According to the driving instructor’s assessment, 52 % of MHE and 61% of patients with Gr I HE were found to be unfit to drive as compared to 25% and 13% of cirrhotics with no HE and controls respectively[60]. However, overall there were discordant results (between psychometric and driving instructor assessment) in 25 out of 94 patients with concordance rates of 62% and 64% between MHE and Gr I HE respectively and the authors concluded, “presence of MHE does not necessarily predict driving fitness and that computer based testing cannot reliably do so either[60].”

Bajaj et al. (2007) using an anonymous self- reported questionnaire (DBQ) coded according to MHE status demonstrated that patients with cirrhosis have significantly higher accidents and violations with MHE patients being at highest risk[61]. Bajaj et al. (2009) building upon their previous work of diagnosing MHE on the basis of Inhibitory control test (ICT) and other standard psychometric tests (SPT) came out with the results of there study done over a 2 year period (retrospective/prospective model) about motor vehicle crashes in cirrhotics with and without MHE[34, 62]. In this study, using either SPT or ICT for diagnosis of MHE patients were divided into MHESPT vs. MHEICT cohort. From the year before and after the testing, the report of collisions from the patients as well as from department of transportation (DOT) was gathered. MHEICT was found to be more highly associated with past and future collisions as compared to SPTMHE and there was great agreement with the self and DOT reports of collisions[34]. Gad et al. also confirmed these results in an Egyptian study.[63]

Linking CHE, simulation and traffic offenses

Lauridsen et al. (2015) study on the largest cohort of cirrhotic patients till date (205 patients) aimed at establishing clarity on the link between driving simulator performance with real-life automobile crashes and traffic violations, to identify what are the features of unsafe MHE drivers and evaluating changes in simulated driving skills in MHE patients after one year. Paper- pencil tests for MHE diagnosis (48% of patients), driving simulation was completed by 163 patients, driving records were collected from the Virginia department of motor vehicles (DMV) and self-reported by patients at the study entry, also questions about alcohol usage/cessation was recorded[64]. Using the DMV records and comparing those to the simulation results the drivers were classified as either safe or unsafe. A higher proportion of subjects with MHE (16%) were categorized as unsafe drivers at baseline than those without MHE (7%); with 18% unsafe vs. 0%, at follow up one year later. On regression analysis, it was found that in MHE patients with recent alcohol cessation (less than a year) having illegal turns during simulator navigation tasks were associated with real-life automobile crashes. The authors concluded, “ Traffic safety counseling should focus on patients with cirrhosis who recently quit consuming alcohol and perform poorly on driving simulation[64].” In the discussion following these results, the authors write that these impaired simulator and real-life traffic outcomes are stable even when followed after a year. Again, MHE patient with shorter history of alcohol cessation (<1yr but >6mo) performing poorly on simulation studies were the ones with the highest rates of real life traffic outcomes. Hence, the argument that “ it is not necessary to deem all the patients with MHE unfit to drive” and the focus of our counseling and restrictions should be directed at this subset of patients with MHE, poor real-driving histories and performance on the driving simulations studies and those who have recently quit alcohol[64].

What is the importance of driving history, which is not always taken?

In patients with cirrhosis and CHE most often the driving history regarding crashes, near misses and other traffic violations is not taken form the patients. The caregivers of these patients who could even be the co-passengers and could fill up on the important details of such driving errors like missing turns, exits and near misses should be made part of this history taking. Taking this history is vital and this will be able to provide valuable information about the severity of CHE to the physician[65]. This history taking by the providers from CHE patients should be ongoing and a repeated dialogue at every visit with a particular focus on discussing their recent driving histories along with results of their driving simulation results if available. This is important as MHE patients tend to forget or lack insight in their problems and this will reinforce and hopefully foster openness to communication and reception of counseling on this sensitive issue by the CHE patients[40, 50, 64]. The overall approach by provider, leaving aside the legality of the issue, towards the driving history should be viewed as important aspect of overall health care and safety of such patients. And this heightened approach may be helpful in reducing adverse outcomes related to this problem. This takes more importance in view of recent findings by Lauridsen et al. who suggested that the traffic crashes in patients with MHE should be treated as a “potential public health issue” meriting openness in this problem basing this argument on the findings that crash rate in their study was higher than the 5% of the annual crash rate of average drivers[64].

What is the utility of screening/testing for patients with MHE as regards to driving?

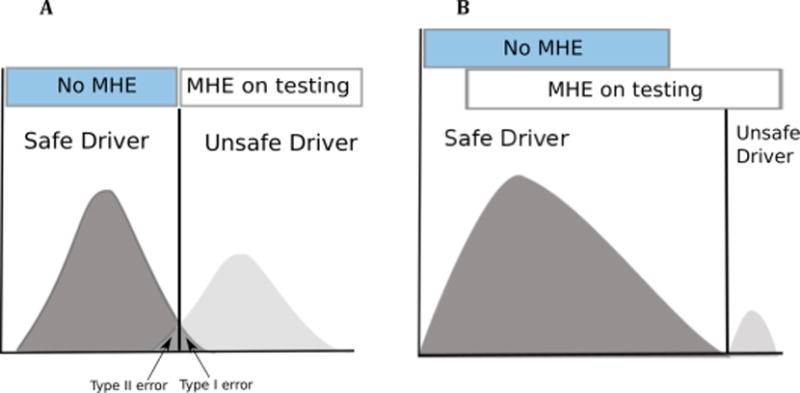

Although there are multiple test available, the problems with the MHE testing are multifold: only few specialized centers in the US offer such tests (ridden with inter/intra observer variability on the cognitive performance), need for time and expertise for conducting and interpreting the results, some tests are costly and under copy right restrictions and there being no single test which can definitely tell us as out of those diagnosed with MHE who will result in real world crashing. In corollary, sole over-reliance on testing will result in some safe MHE patients being wrongly, labeled as unfit to drive (type 1 error) and vice versa (type 2 error) while as the vast majority of patient with MHE are safe to drive (Fig. 2)[39]. It is hoped that with advances in the field of MHE testing will result in finding some consensus towards the “gold standard” testing. Current, CHE testing strategies include three types of tests: a) Paper-pencil tests examples include: Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (PHES), Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) b) Computerized tests examples include: Inhibitory Control Test (ICT), The EncephalApp Stroop Test (EncephalApp Stroop), Scan test c) Neuro-physiological tests examples include: Critical flicker frequency (CFF) test, electroencephalogram (EEG)[5]. At this time by consensus, at least two validated tests (PHES and one of the computerized or neurophysiological tests) should be used for multicenter studies while for single center studies or clinical evaluation a validated test depending on the local familiarity with the test may be used[7]. Only properly trained persons should administer the tests and repeat testing for CHE or MHE should be done within 6 months if testing for these was negative initially[38].

Figure 2.

Issues with MHE tests and driving: Far from all MHE patients are dangerous drivers. (A) When relying blindly on a cognitive test, safe drivers will in some cases be deemed unfit to drive (type I error) and vice versa (type II error). (B) In reality, only a few MHE patients will prove to be unfit to drive.

(Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons Ltd, Lauridsen MM, Wade, James B, Bajaj, Jasmohan S. What is the Ethical (Not Legal) Responsibility of a Physician to Treat Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Advise Patients Not to Drive? Clinical Liver Disease. 2015;6:86–89).

Lauridsen et al. (2015) using an electronic questionnaire to find out the diagnosis and management of HE and its effect on driving ability world-wide got a response rate of 35% (23 countries across 4 continents) from HE experts: Only 60 % physicians engage in some screening of their CHE patients but only 10% refer for formal testing mostly in a focused group of patients mainly when quality of life was involved, PHES and CFF are the most common tests used by 41% and 37% respectively with PHES, Stroop EncephalApp and CFF being the most used tests in Europe, America and Asia respectively[66, 67]. The 40% physicians who did not use any kind of screening for CHE cited various reasons including time constraints, lack of technical expertise and lack of consensus for not doing so, this was even when 99% of them agreed that both CHE and OHE had adverse effects on driving skills[66]. Bajaj et al. (2007), used an AASLD survey to find the approach towards MHE testing and barriers thereof in USA, found that despite the majority of members acknowledging that MHE was a significant problems yet only a minority of physicians tested for it > 50% time with 38% responding that they never tested for it citing more or less the same reasons as above[68]. However, the results from the more recent survey show that the situation in this regard has shown some improvement in the Americas[66].

The EncephalApp Stroop Test, which is a popular test in US measures psychomotor speed and cognitive flexibility evaluating the functioning of the anterior attention system[43]. Also Stroop mobile application for smart phone or tablet computer (EncephalApp Stroop) has been used as a valid tool to screen for CHE compared to conventional paper-pencil tests[69]. A recent study by the same group demonstrated that EncephalApp has good face validity, test-retest reliability, and external validity for the diagnosis of CHE[70]. A more recent study has now validated EncephalApp in a multicenter setting as compared to existing gold standard tests as having good sensitivity for MHE diagnosis along with capability to predict development of OHE[71]. This “app” is available for free download on iTunes and is not only easy to administer but also simple to score and interpret. The details of this test can be viewed as webcasts at www.chronicliverdisease.org. Several of these tests, including ICT and EncephalApp, have been linked with driving performance on a simulator[35, 70].

Is there any benefit in treating patients with CHE as regards to driving?

As per current guidelines the consideration to treat a patient of CHE with medications is done on case- to- case basis by the providers[5]

Prasad et al. (2007) in a non- blind study gave either lactulose or no treatment in MHE patients and studied them over 3 months trying to find if this helps in the cognitive and health- related quality of life (HRQOL)[72]. In this study, psychometric testing and Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) was done at the start and the end of the study, they found that in patients with MHE, lactulose improves both cognitive function and HRQOL. Bajaj et al. (2011) examined the question about whether rifaximin improves the performance on driving simulation in MHE patients in a double blind placebo controlled trail[73]. In this study, which lasted 8 weeks driving simulation was done at the beginning and at the end: cognitive abilities, quality of life, Lab values and MELD were analyzed. The avoidance of total driving errors, speeding and illegal turns were significantly found to be lower in the rifaximin group as compared to the placebo group. There was 91% improvement in their cognitive performance in the rifaximin group as compared to 61% of patients in the placebo group and a high adherence of 92% in the study[73]. Sharma et al. (2014) conducted a two phase randomized study over two months to determine prevalence of MHE and to compare placebo to individual effects of rifaximin, probiotics, and l-ornithine l-aspartate (LOLA) in MHE patients[74]. In this sub group of patients the prevalence of MHE was around 60% and it was found that all the agents showed improvement in percentage on the Psychometric testing as follows LOLA (67.7%) rifaximin (70.9%), probiotics (50%) as compared to placebo (30%) and are better than giving placebo in patients with MHE[74]. Bajaj et al. (2008) had demonstrated that gut microflora modification by a food, probiotic yogurt helped in significant reversal of MHE with excellent adherence (88%) and potential for long term adherence[75].

Bajaj et al. (2012) study using a driving simulator aimed at evaluating the change in the self- assessment of driving skills (SADS) concluded, “Insight into driving skills in cirrhosis improves after driving simulation and is highest in those with navigation errors and MHE on ICT[76].” Andersen et al. (2013) using a prospective sample of 19 alcoholic patients and establishing them in an outpatient rehabilitation clinic post HE survival and compared their outcome to a control group of regularly discharged patients and found that survival was significantly improved for patients in the study group which resulted in cost savings in future hospital admissions[77]. In patients with stroke and brain injury, simulation training resulted in improved performance in live driving simulation[78]. The above studies also shows that cognitive rehabilitation by driving simulator-associated insight improves driving skills in cirrhosis and post discharge rehabilitation may hold a promising role in the future[76, 77].

Bajaj et al. (2012) conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis for reducing motor vehicle accident (MVA)-related societal costs using a Markov model, following a simulated cohort of one thousand cirrhotic patients for five years with twice a year MHE testing and comparing various (five) MHE management strategies and concluded, “detection of MHE by using the ICT, and subsequent treatment with lactulose could substantially reduce societal costs by preventing MVA’s[79].” In this study, it was found that a single MVA costs the society around $42,100 and total cost/MVA prevented was the lowest for ICT and lactulose strategy with a net saving of $ 1.7 million over 5 years[79]. The results of above two studies show that there are cost savings at the societal level with these strategies[77, 79].

The worldwide survey study found that most of the physicians still initiate treatment for their CHE patients on case-to-case basis but less than 5% of them treated patients in the last one month fulfilling the local treatment criteria[66]. The authors concluding, “this could reflect the gap between knowledge, attitudes and the ultimate translation into practice[66].” Which connotes that ongoing work needs to be done in this area for narrowing this gap. In the same study, the medications used to treat CHE all over the world vs. in the Americas (in percent) are lactulose 94 vs. 79, rifaximin 53 vs. 57, branched chain amino acids 21 vs. 0, probiotics 15 vs. 21 and LOLA 15 vs. 11%[66]. Lactulose and rifaximin are the two leading medications used in the Americas and the world over however, BCCA and LOLA are largely unavailable in the Americas leading to no to very less usage respectively.

The above discussions show that there may be some improvement in the driving skills of MHE patients with treatment, which could result in cost savings at a societal level.

What are the ethical and legal responsibilities for physicians?

There is no formal curriculum to train physicians during the residency training about how to evaluate patient’s fitness to drive and hence they lack the skills to do so. The decision to advise a patient not to drive during episodes of OHE may not be hard for the physician. However, in CHE this gets murkier in the sense that there are no clear-cut guidelines to follow. Again, even after successful therapy for an episode of OHE, not only is there persistence of residual cognitive issues but also treated OHE patients can easily be tipped over by precipitants to get recurrent episodes of OHE [80–82]. Compounding this difficulty is the lack of insight these patient’s exhibit in their deficits[50]. All of these factors can potentially lead to deleterious consequences to self and for the society if these patients keep on driving. This dilemma has been well captured in a recent review where in it has been argued that ethical principles (of beneficence, non-malfeasance, justice and autonomy) need to be adhered to while addressing the question of driving in MHE patients[39]. The physician has to be able to use his best judgment and be able to maintain a balance between his ethical duties to wards his patients and the society[39]. This becomes more important as one examines the legality behind reporting the medically impaired drivers. Cohen et al. (2011), reported that only six states (12%) namely: California, Delaware, Nevada, New Jersey, Oregon and Pennsylvania required physicians to report drivers with medical impairments and there is no uniform law across the states, however all of these six states provided legal immunity to the physicians for reportage to the motor vehicle department[83]. However, none of the motor vehicle codes mentioned HE specifically for automatic reporting in any state and permissive reporting and no reporting statues were found in 35(70%) and 9(18%) states respectively and out of these only some states 25(44%) offered the legal immunity to the physician[83]. However, a recent study reports that 8(16%) states require physicians to report cognitively impaired drivers mandatorily adding Georgia and Maryland to the earlier list with there being legal immunity extended to physician in all the states except Georgia from this list[84]. In the accompanying editorial to the Cohen article, Bajaj et al. argue that even as HE is not specifically mentioned in state DMV’s but patients with recent OHE, but not necessarily CHE, will come under the ambit of people with “lapses of consciousness.” And as physicians are not trained to assess fitness to drive and do not act on behalf of the state to do so, but if the provider is concerned, the best course of action is to ask the patient to stop driving with involvement of the caregiver in the discussion and to refer the difficult cases to the proper driving authorities for resolution. There are some academic centers where there is availability of expertise and equipment for conducting such testing but the final authority for such determination lies with the state driving licensing agencies[5, 40].

The AMA in 2010 came out with an updated guidance document for assessment and counseling of elderly drivers in regards to their driving safely. Although, this document does not specifically address patients with HE either overt or covert but is a useful tool for physicians working in this area and goes over the regulations at state levels for elderly drivers who could be potentially impaired[85].

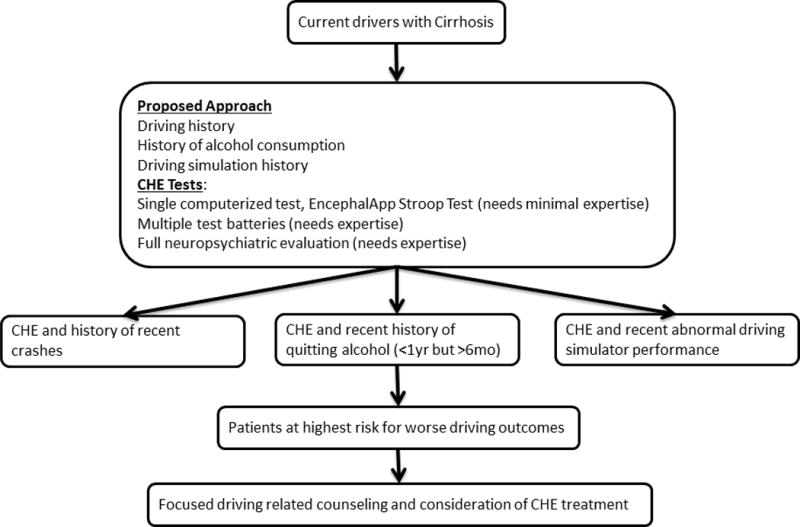

As per above discussion and examination of evidence at this time it is not desirable to recommend laws against driving in all the patients with CHE, as still there is no full consensus upon as to what are the best tests for diagnosis and even all the patients who are diagnosed with CHE do not necessarily fall into the “no-driving” category. Hence, a focused approach is desired and deciding on case to case basis as to who are the patients out of the pool on whom maximal efforts in terms of screening, testing, counseling and treatments may need to be directed. An algorithmic approach to CHE drivers for focused counseling and consideration for treatment is proposed (Fig. 3). Again, with treatment some of the CHE patients may re-gain the capacity for safe driving which opens up the discussion for re-certifying them for return back to the driving force. It appears, there is need for ongoing well-designed studies to gain better evidence, as there still are a lot of unanswered questions. Until that time arrives, physicians are not absolved of the duty to counsel their HE patients about the dangers of driving to self and to others preferably while involving their caregivers, and upholding the local laws. Physicians also have to play an ongoing role in educating the lay public and the law -makers about the impact of driving impairment on the society and the need for enacting new laws in this regard.

Figure 3.

Algorithm showing approach for focused driving related counseling and consideration of treatment in CHE patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This research was partly supported by grants from the NIH (RO1DK089713) and VA (CX10076) to JSB

References

- 1.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The Epidemiology of Cirrhosis in the United States: A Population-based Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:690–696. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asrani SK, Larson JJ, Yawn B, et al. Underestimation of liver-related mortality in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:375–382. e371–372. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gines P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, et al. Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1987;7:122–128. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stepanova M, Mishra A, Venkatesan C, et al. In-hospital mortality and economic burden associated with hepatic encephalopathy in the United States from 2005 to 2009. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1034–1041 e1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715–735. doi: 10.1002/hep.27210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj JS, Wade JB, Sanyal AJ. Spectrum of neurocognitive impairment in cirrhosis: Implications for the assessment of hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2009;50:2014–2021. doi: 10.1002/hep.23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajaj JS, Cordoba J, Mullen KD, et al. Review article: the design of clinical trials in hepatic encephalopathy–an International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism (ISHEN) consensus statement. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:739–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Verber MD, et al. Inhibitory control test is a simple method to diagnose minimal hepatic encephalopathy and predict development of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:754–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer T, Eshelman A, Abouljoud M. Neuropsychological changes in a large sample of liver transplant candidates. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3559–3560. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero-Gomez M, Boza F, Garcia-Valdecasas MS, et al. Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy predicts the development of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2718–2723. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saxena N, Bhatia M, Joshi YK, et al. Electrophysiological and neuropsychological tests for the diagnosis of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy and prediction of overt encephalopathy. Liver. 2002;22:190–197. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2002.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patidar KR, Thacker LR, Wade JB, et al. Covert hepatic encephalopathy is independently associated with poor survival and increased risk of hospitalization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1757–1763. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajaj JS, Riggio O, Allampati S, et al. Cognitive dysfunction is associated with poor socioeconomic status in patients with cirrhosis: an international multicenter study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1511–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roman E, Cordoba J, Torrens M, et al. Falls and cognitive dysfunction impair health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:77–84. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283589f49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desapriya E, Subzwari S, Fujiwara T, et al. Conventional vision screening tests and older driver motor vehicle crash prevention. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2008;15:124–126. doi: 10.1080/17457300802150926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall SC. The role of reduced fitness to drive due to medical impairments in explaining crashes involving older drivers. Traffic Inj Prev. 2008;9:291–298. doi: 10.1080/15389580801895244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson CA, Wilkinson ME. Vision and driving: the United States. J Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30:170–176. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181df30d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desapriya E, Harjee R, Brubacher J, et al. Vision screening of older drivers for preventing road traffic injuries and fatalities. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD006252. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006252.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rumschlag G, Palumbo T, Martin A, et al. The effects of texting on driving performance in a driving simulator: the influence of driver age. Accid Anal Prev. 2015;74:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawson JD, Anderson SW, Uc EY, et al. Predictors of driving safety in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72:521–527. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341931.35870.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marottoli RA, Cooney LM, Jr, Wagner R, et al. Predictors of automobile crashes and moving violations among elderly drivers. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:842–846. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-11-199412010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uc EY, Rizzo M, Anderson SW, et al. Driving with distraction in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1774–1780. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000245086.32787.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Ageing and transport: mobility needs and safety issues. Paris, France: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizzo M. Impaired driving from medical conditions: a 70-year-old man trying to decide if he should continue driving. JAMA. 2011;305:1018–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marottoli RA, Mendes de Leon CF, Glass TA, et al. Driving cessation and increased depressive symptoms: prospective evidence from the New Haven EPESE. Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.2014 Crash Data Key Findings. 2015 Nov [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh S. Critical reasons for crashes investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey. 2015 Feb [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deaths for the twelve-month period ending June 2015. USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bajaj JS, Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, et al. Deleterious effect of cirrhosis on outcomes after motor vehicle crashes using the nationwide inpatient sample. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1674–1681. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gitlin N, Lewis DC, Hinkley L. The diagnosis and prevalence of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in apparently healthy, ambulant, non-shunted patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1986;3:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(86)80149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das A, Dhiman RK, Saraswat VA, et al. Prevalence and natural history of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:531–535. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortiz M, Jacas C, Cordoba J. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: diagnosis, clinical significance and recommendations. J Hepatol. 2005;42(Suppl):S45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quero JC, Schalm SW. Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Semin Liver Dis. 1996;16:321–328. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Schubert CM, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy is associated with motor vehicle crashes: the reality beyond the driving test. Hepatology. 2009;50:1175–1183. doi: 10.1002/hep.23128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, et al. Navigation skill impairment: Another dimension of the driving difficulties in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2008;47:596–604. doi: 10.1002/hep.22032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Zadvornova Y, et al. The effect of fatigue on driving skills in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:898–905. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wein C, Koch H, Popp B, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy impairs fitness to drive. Hepatology. 2004;39:739–745. doi: 10.1002/hep.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prakash RK, Brown TA, Mullen KD. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy and driving: is the genie out of the bottle? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1415–1416. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lauridsen MM, Wade James B, Bajaj Jasmohan S. What is the Ethical (Not Legal) Responsibility of a Physician to Treat Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy and Advise Patients Not to Drive? Clinical Liver Disease. 2015;6:86–89. doi: 10.1002/cld.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bajaj JS, Stein AC, Dubinsky RM. What is driving the legal interest in hepatic encephalopathy? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maguire EA, Burgess N, Donnett JG, et al. Knowing where and getting there: a human navigation network. Science. 1998;280:921–924. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weissenborn K, Giewekemeyer K, Heidenreich S, et al. Attention, memory, and cognitive function in hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2005;20:359–367. doi: 10.1007/s11011-005-7919-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amodio P, Schiff S, Del Piccolo F, et al. Attention dysfunction in cirrhotic patients: an inquiry on the role of executive control, attention orienting and focusing. Metab Brain Dis. 2005;20:115–127. doi: 10.1007/s11011-005-4149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nyberg SL, B-B E, Mitchell MM, Bida JP, Schneider NK, Smith GE, et al. Early experience with HEADS: Hepatic encephalopathy assessment driving simulator. Advances in Transportation Studies. 2006:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arguedas MR, DeLawrence TG, McGuire BM. Influence of hepatic encephalopathy on health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1622–1626. doi: 10.1023/a:1024784327783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reimer B, D’Ambrosio LA, Coughlin JF, et al. Task-induced fatigue and collisions in adult drivers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Traffic Inj Prev. 2007;8:290–299. doi: 10.1080/15389580701257842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barkley RA, Guevremont DC, Anastopoulos AD, et al. Driving-related risks and outcomes of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescents and young adults: a 3- to 5-year follow-up survey. Pediatrics. 1993;92:212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Philip P, Sagaspe P, Taillard J, et al. Fatigue, sleepiness, and performance in simulated versus real driving conditions. Sleep. 2005;28:1511–1516. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.12.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Dupaul GI, et al. Driving in young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: knowledge, performance, adverse outcomes, and the role of executive functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:655–672. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702801345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Hafeezullah M, et al. Patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy have poor insight into their driving skills. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1135–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.025. quiz 1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prochaska JORCEK. The transtheoretical model and stages if change. Jossey-Bass, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ries ML, Jabbar BM, Schmitz TW, et al. Anosognosia in mild cognitive impairment: Relationship to activation of cortical midline structures involved in self-appraisal. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:450–461. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:826–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950100074007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, et al. Insight and danger in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:455–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Montoliu C, Piedrafita B, Serra MA, et al. IL-6 and IL-18 in blood may discriminate cirrhotic patients with and without minimal hepatic encephalopathy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:272–279. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815e7f58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schomerus H, Hamster W, Blunck H, et al. Latent portasystemic encephalopathy. I. Nature of cerebral functional defects and their effect on fitness to drive. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:622–630. doi: 10.1007/BF01367675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haussinger D, Schliess F. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hepatic encephalopathy. Gut. 2008;57:1156–1165. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Srivastava A, Mehta R, Rothke SP, et al. Fitness to drive in patients with cirrhosis and portal-systemic shunting: a pilot study evaluating driving performance. J Hepatol. 1994;21:1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe A, Tuchida T, Yata Y, et al. Evaluation of neuropsychological function in patients with liver cirrhosis with special reference to their driving ability. Metab Brain Dis. 1995;10:239–248. doi: 10.1007/BF02081029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kircheis G, Knoche A, Hilger N, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy and fitness to drive. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1706–1715. e1701–1709. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a vehicle for accidents and traffic violations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1903–1909. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Franco J, et al. Inhibitory control test for the diagnosis of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1591–1600 e1591. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gad YZ, Zaher AA, Moussa NH, et al. Screening for minimal hepatic encephalopathy in asymptomatic drivers with liver cirrhosis. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2011;12:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lauridsen MM, Thacker LR, White MB, et al. In Patients with Cirrhosis, Driving Simulator Performance Is Associated With Real-life Driving. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bajaj JS. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy matters in daily life. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3609–3615. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lauridsen MM, Bajaj JS. Hepatic encephalopathy treatment and its effect on driving abilities: A continental divide. J Hepatol. 2015;63:287–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sharma P, Sharma BC. A survey of patterns of practice and perception of minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a nationwide survey in India. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:304–308. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.141692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bajaj JS, Etemadian A, Hafeezullah M, et al. Testing for minimal hepatic encephalopathy in the United States: An AASLD survey. Hepatology. 2007;45:833–834. doi: 10.1002/hep.21515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bajaj JS, Thacker LR, Heuman DM, et al. The Stroop smartphone application is a short and valid method to screen for minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2013;58:1122–1132. doi: 10.1002/hep.26309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Sterling RK, et al. Validation of EncephalApp, Smartphone-Based Stroop Test, for the Diagnosis of Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1828–1835 e1821. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allampati S, Duarte-Rojo A, Thacker LR, et al. Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Using Stroop EncephalApp: A Multicenter US-Based, Norm-Based Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:78–86. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prasad S, Dhiman RK, Duseja A, et al. Lactulose improves cognitive functions and health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis who have minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2007;45:549–559. doi: 10.1002/hep.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Wade JB, et al. Rifaximin improves driving simulator performance in a randomized trial of patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:478–487 e471. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharma K, Pant S, Misra S, et al. Effect of rifaximin, probiotics, and l-ornithine l-aspartate on minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:225–232. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.136975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Christensen KM, et al. Probiotic yogurt for the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1707–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bajaj JS, Thacker LR, Heuman DM, et al. Driving simulation can improve insight into impaired driving skills in cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:554–560. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1888-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andersen MM, Aunt S, Jensen NM, et al. Rehabilitation for cirrhotic patients discharged after hepatic encephalopathy improves survival. Dan Med J. 2013;60:A4683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kewman D. Simulation training of psychomotor skills:teaching the brain-injured to drive. Rehabil Psychol. 1985;30:11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bajaj JS, Pinkerton SD, Sanyal AJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy to prevent motor vehicle accidents: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Hepatology. 2012;55:1164–1171. doi: 10.1002/hep.25507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bajaj JS, Schubert CM, Heuman DM, et al. Persistence of cognitive impairment after resolution of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2332–2340. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bajaj JS. Review article: the modern management of hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:537–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy–definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35:716–721. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohen SM, Kim A, Metropulos M, et al. Legal ramifications for physicians of patients who drive with hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.08.002. quiz e117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vierling JM. Legal Responsibilities of Physicians When They Diagnose Hepatic Encephalopathy. Clin Liver Dis. 2015;19:577–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.American Medical Association. Physician’s guide to assessing and counseling older drivers. 2010 [Google Scholar]