Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-specific death in the United States. Evidence suggests people with mental illness are less likely to receive preventive health services, including cancer screening. We hypothesized that mental illness is a risk factor for nonadherence to colorectal cancer screening guidelines.

Methods

We analyzed results of the 2007 California Health Interview Survey to test whether mental illness is a risk factor for non-adherence to colorectal cancer screening recommendations among individuals age 50 or older (N = 15,535). This cross-sectional dataset is representative of California. Screening was defined as either fecal occult blood testing during the preceding year, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy during the preceding 5 years. Mental illness was identified using the Kessler K6 screening tool. Associations were evaluated using weighted multivariate logistic regressions.

Results

Mental illness was not associated with colorectal cancer screening adherence (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.63-1.25). Risk factors for nonadherence included being female (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.44); delaying accessing health care during the previous year (OR; 1.89; 95% CI, 1.56-2.29).

Conclusions

Unlike previous studies, this study did not find a relationship between mental illness and colorectal cancer screening adherence. This could be due to differences in study populations. State-specific health care policies involving care coordination for individuals with mental illness could also influence colorectal cancer screening adherence in California.

Keywords: Cancer Screening, health disparities, vulnerable populations

Introduction

In the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer diagnosed in men and women and the second leading cause of cancer-specific death.1 Since 2002, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended CRC screening as an essential prevention tool to decrease the incidence, morbidity, and mortality rates of CRC.2 Despite evidence that early detection of invasive disease via colonoscopy reduces mortality, a majority of U.S. adults do not receive regular risk-appropriate screening, or have never been screened.3,4 At the population level, lack of health insurance and awareness of the importance of CRC screening have been identified as primary barriers to CRC screening.5

People living with serious mental illness in the United States have an increased risk of a range of chronic conditions.6, 7 Individuals with mental illness encounter numerous barriers to accessing health care, which could negatively influence adherence to CRC screening guidelines among this population.8 These barriers include limitations in training of health care professionals related to assisting patients with mental illness9,10 and limited access to primary and preventive health services.11

Resulting from limited access to health care, individuals with mental illness are less likely than other groups to obtain screening for a range of cancers.12 One study reported that veterans with mental disorders were less likely to receive CRC screenings compared to those without.13 Another study of mental health consumers in California reported that cancer screening services were underused, particularly for CRC.14 Whether these findings are generalizable is unclear and limited research has been conducted on this topic using population-based data.

Because of the known health disparities, guidelines have specified the need for improving the monitoring of physical health conditions for people with serious mental illness.15 Monitoring can facilitate illness prevention by detecting a disease’s warning signs, and can also be an avenue to self-management of chronic disease. Further, the Affordable Care Act has emphasized precisely this type of prevention for vulnerable populations. The present study analyzed population-based data from the 2007 wave of the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) 16 to evaluate whether having a mental illness was associated with a decreased likelihood of obtaining CRC screening. We hypothesized that having a mental illness would be associated with lower levels of CRC screening.

Methods

Data Source

This cross-sectional observational study analyzed data drawn from the 2007 CHIS.16 CHIS is a population-based telephone survey conducted in California every other year since 2001, and covers topics related to access to health care, health status, and health behaviors. The 2007 wave included interviews with more than 48,000 adults from every county in California. CHIS investigators weighted respondents to align the sample’s demographic characteristics with state data from the 2000 Census and to adjust for the likelihood of having a telephone.16 The adult interview completion rate for 2007 was 52.8% (landline) and 52% (cell phone) for adults, which is comparable to response rates of other scientific telephone surveys in California.16 Eligible households included houses, apartments, and mobiles homes occupied by individuals, families, multiple families, extended families, or multiple unrelated individuals if fewer than 9. Individuals living in households without telephone service, group quarters, criminal justice or other institutions, transient or temporary arrangements, or military barracks and those experiencing homelessness were not eligible.16

Study Population

The present study includes respondents, age 50 or older who had received a recommendation from their doctor to be screened for CRC during the previous 5 years. Our rationale follows the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for CRC screening, which indicate that CRC screening is only necessary for people age 50 or older.17

Independent and Control Variables

Our independent variable of interest was having a mental illness, identified using the Kessler K6, which the CHIS uses to screen for mental illness among survey respondents.18 The K6 has been used in many epidemiological studies to identify serious mental illness, defined as having a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder meeting DSM-IV criteria other than a substance abuse disorder that resulted in serious impairment, with a global assessment of functioning less than 60 in the past 12 months. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends using the K6 to screen for mental illness in primary and specialty health care settings, and is also used to allocate funds to community mental health settings. 19 As in previous studies18 participants with a K6 score ≥ 13 were coded as having a mental illness.

Mandelblatt’s model of equitable access to cancer services20 guided our selection of control variables. This model uses the principles of Andersen’s21 and Aday, Andersen, and Fleming’s22 behavioral model and suggests that patient-level factors such as age and comorbidity, and provider-level characteristics such as use of practice guidelines can influence cancer screening outcomes.

Demographic characteristics included gender, age, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. As in previous CRC screening adherence studies, 23 age was categorized into three levels: 50–65, 66–74, and 75–85. To accurately depict California’s racial and ethnic composition, our race/ethnicity variable included: non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, black, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other. As in previous studies23 we classified education as less than high school, high school diploma, bachelor’s degree, and more than college. We also controlled for self-rated health, which was dichotomized as excellent, very good, or good as one category and fair or poor as the other category.

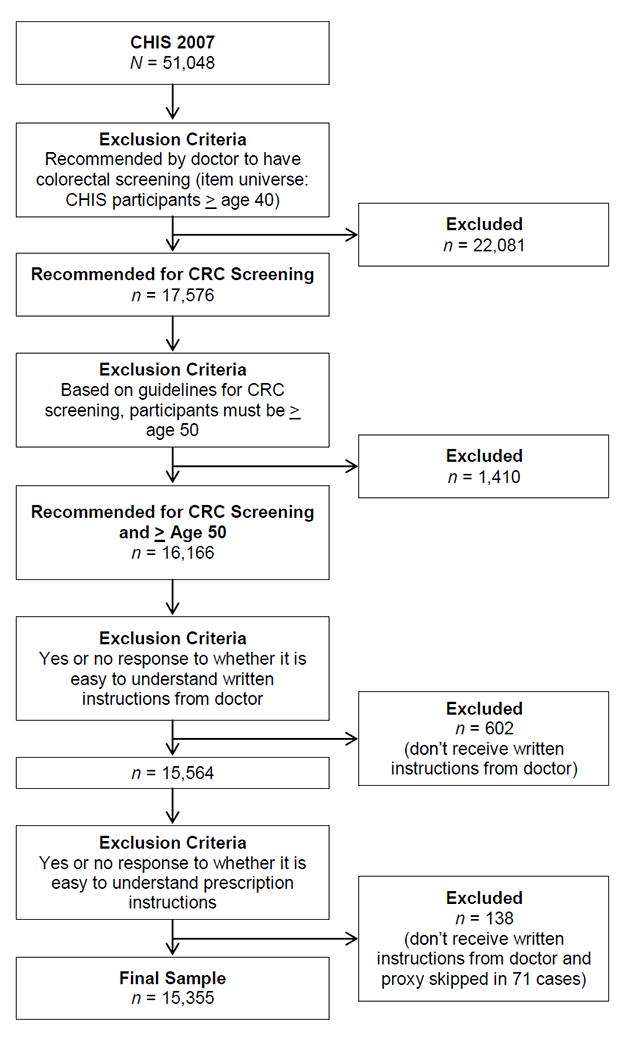

The equitable access to cancer care model specifies an individual’s access to health care as a key predictor for using cancer-screening services. We included four variables that represent an individual’s access to care: (1) whether an individual has difficulty understanding written instructions from a doctor; (2) whether an individual has difficulty understanding prescription instructions; (3) whether an individual has delayed health care for any reason; and (4) insurance stability. The CHIS 2007 asks respondents whether they have difficulty understanding instructions from their doctor or understanding prescription instructions. Response options were “Yes,” “No,” and “I don’t receive instructions from my doctor,” or “I don’t get prescription instructions.” As in previous studies,23 we excluded respondents who reported that they don’t receive instructions from their doctor or don’t receive prescription instructions for ease of interpretability. Yes-or-no responses were also recorded for delaying accessing health services for any reason and respondents’ insurance status during the previous year. Selection of study participants is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study population flow chart

Dependent Variable

Our dependent variable was adherence to CRC screening guidelines. CHIS 2007 respondents were asked three questions related to their adherence to CRC screening, which ascertained whether a respondent had a colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or a blood stool test during the previous 5 years. Using these three questions, the CHIS 2007 created a dichotomous variable indicating whether respondents did or did not adhere to CRC screening recommendations.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population and prevalence of CRC screening adherence. Differences between study participants with and without mental illness were calculated using Rao-Scott Chi squares to account for sample weights. Weighted logistic regression analyses were then used to model the association between having mental illness and CRC screening adherence, while adjusting for demographic characteristics, health literacy, health access, and self-rated health. We include results from a partially adjusted model that included having a mental illness, sex, age, and race/ethnicity, and from a fully adjusted model which included all covariates described above. Estimates were obtained using sample weights included in the CHIS public use files. Finally, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether higher cutoff points of the K6 scale were associated with colorectal cancer screening adherence.

Because our a priori analysis only included CHIS 2007 participants age 50 or older who had received a recommendation for CRC screening, we also conducted a post hoc analysis among all CHIS participants age 50 or older to determine whether mental illness was associated with CRC screening using a broader study population. In our post-hoc analysis, a recommendation for CRC screening was considered a covariate in the weighted logistic regression model. We report odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). P-values were two-sided and statistical significance was set at .05. Data cleaning was conducted using SPSS version 21.24 All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 with the procsurveyfreq and procsurveylogistic procedures.25

Results

Among the 51,048 respondents in the 2007 CHIS, 22,081 were not recommended by their physician to get CRC screening. Of the 17,576 that received recommendations to undergo CRC screening by their health care provider, 16,166 were age 50 or older. After excluding patients who did not receive instructions or prescriptions from their health care provider, 15,355 respondents were included in the analysis.

Descriptive Results

Demographic comparisons of participants with and without mental illness, who are age 50 and older, and have received recommendations for CRC screening are shown in Table 1. Six percent of the study sample had K6-score of ≥13, indicating presence of a mental illness. CRC screening adherence was reported by 78% of the participants. A higher proportion of individuals who screened positive for mental illness reported being female (66% vs 52% Rao-Scott χ2 = 17.91, p<0.0001); having a high school education (53% vs 48%; Rao-Scott χ2 = 44.60, p<0.0001) or less than a high school education (24% vs 16%; Rao-Scott χ2 = 44.60, p<0.0001); poor self-rated health (55% vs 21%; Rao-Scott χ2 = 131.6; p<0.0001); difficulty understanding prescription instructions (14% vs 6%; Rao-Scott χ2 = 31.23; p<0.0001), delaying receiving health care in the past year (34% vs 14%; Rao-Scott χ2 = 77.09; p<0.0001), and being uninsured in the past year (10% vs 4%; Rao-Scott χ2 = 24.87; p<0.0001). A lower proportion of individuals who screened positive for mental illness reported being non-Hispanic white (61% vs 69% Rao-Scott χ2 = 24.79 p<0.0001); and reported being 75-85 (6% vs 16% Rao-Scott χ2= 138.02, p<0.0001);

Table 1.

Characteristics of CHIS 2007 Respondents Age 50-85 Recommended for CRC Screening by Health Care Provider (N = 15,355)

| Total | K6 postive | K6 negative | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 15,355) | (n = 941) | (n = 14,414) | |||||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | Rao-Scott χ2 | df | P |

| Mental illness | |||||||||

| K6 positive | 941 | 6.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| K6 negative | 14,414 | 94.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sex | 17.91 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Male | 6,076 | 46.8 | 263 | 33.8 | 5,813 | 47.7 | |||

| Female | 9,279 | 53.1 | 678 | 66.2 | 8,601 | 52.3 | |||

| Age | 138.02 | 2 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 50–65 | 8,811 | 65.9 | 752 | 83.4 | 8,059 | 64.8 | |||

| 66–74 | 3,545 | 18.8 | 113 | 10.1 | 3,432 | 19.4 | |||

| 75–85 | 2,999 | 15.2 | 76 | 6.4 | 2,923 | 15.8 | |||

| Race and ethnicity | 24.79 | 4 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| non-Hispanic white | 12,229 | 69.0 | 676 | 61.3 | 11,553 | 69.5 | |||

| Hispanic | 1,247 | 14.6 | 125 | 21.4 | 1,122 | 14.2 | |||

| Asian or Pacific Islander |

785 | 9.3 | 32 | 5.6 | 753 | 9.6 | |||

| Black | 636 | 4.9 | 49 | 6.9 | 587 | 4.8 | |||

| Other | 455 | 2.9 | 59 | 4.8 | 399 | 1.8 | |||

| CRC screening adherence | 1.00 | 2 | 0.319 | ||||||

| Adherent | 12,275 | 78.1 | 719 | 24.6 | 11,556 | 21.7 | |||

| Nonadherent | 3,080 | 21.8 | 222 | 75.4 | 2,858 | 78.3 | |||

| Education | 44.60 | 3 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Less than high school |

904 | 10.0 | 114 | 17.8 | 790 | 9.9 | |||

| High school graduate |

7,433 | 48.2 | 554 | 56.4 | 6,879 | 47.7 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 3,566 | 21.8 | 146 | 14.2 | 3,420 | 22.2 | |||

| More than bachelor’s degree | 3,452 | 19.7 | 127 | 11.6 | 3,325 | 20.2 | |||

| Self-rated health | 131.60 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Good | 12,173 | 76.8 | 439 | 44.4 | 11,734 | 79.0 | |||

| Poor | 3,182 | 23.1 | 502 | 55.5 | 2,680 | 21.0 | |||

| Understand prescription instructions | 31.23 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Easy | 14,437 | 93.2 | 823 | 85.7 | 13,614 | 93.8 | |||

| Difficult | 918 | 6.7 | 118 | 14.3 | 800 | 6.2 | |||

| Delayed care during previous year | 77.09 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Delayed | 2,201 | 14.3 | 339 | 34.6 | 1,862 | 13.7 | |||

| Not delayed | 13,154 | 85.7 | 602 | 65.3 | 12,552 | 86.3 | |||

| Insurance status during previous year | 24.87 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Insured for entire year | 14,796 | 95.5 | 846 | 90.4 | 13,950 | 95.8 | |||

| Uninsured at any point | 559 | 4.4 | 95 | 9.5 | 464 | 4.1 | |||

Abbreviations: CHIS, California Health Interview Survey; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Weighted to account for complex survey design and accurately represent California population. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding error.

Factors associated with CRC Screening among Participants who Received Screening Recommendations

Table 2 shows the results for the factors associated with CRC in the CHIS 2007. Comparison of factors from partially adjusted vs fully adjusted model show that the OR for having a mental illness was not significant in either model, (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.70-1.37 vs OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.63-1.25). In both the partially and fully adjusted models, being female was a risk factor for non-adherence (OR, 1.27; 95%CI, 1.11-1.45 vs OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.44). In both the partially and fully adjusted models, being age 66-74 vs 50-65 increased likelihood screening adherence (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.37-0.55 vs OR, 0.51 95% CI, 0.42-0.62), as did being 75-85 vs 50-65 (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.32-0.47 vs OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.42-0.62). In the fully adjusted model, delaying care for any reason in the past year was a risk factor for non-adherence (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.56-2.29), whereas having insurance stability (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, (0.37-0.70), and poor self-rated health (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.96) increased odds of adherence. Odds ratios and 95% Confidence intervals are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Adherence to CRC Screening among CHIS 2007 Respondents Age 50-85 Recommended for CRC Screening by Health Care Provider

| Partially Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| K6 positive | 0.97 | 0.70-1.37 | 0.890 | 0.89 | 0.63-1.25 | 0.489 |

| Female | 1.27 | 1.11-1.45 | 0.0006 | 1.25 | 1.09-1.44 | 0.0017 |

| Age | ||||||

| 66–74 | 0.46 | 0.37-0.55 | <0.0001 | 0.51 | 0.42-0.62 | <0.0001 |

| 75–85 | 0.39 | 0.32-0.47 | <0.0001 | 0.45 | 0.38-0.55 | <0.0001 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.14 | 0.91-1.43 | 0.258 | 1.18 | 0.93-1.49 | 0.173 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.14 | 0.86-1.51 | 0.376 | 1.20 | 0.90-1.60 | 0.211 |

| Black | 1.03 | 0.73-1.46 | 0.870 | 0.99 | 0.91-1.38 | 0.945 |

| Other | 1.21 | 1.11-1.45 | 0.333 | 1.21 | 0.82-1.78 | 0.330 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school graduate | 1.05 | 0.80-1.38 | 0.713 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 1.20 | 0.89-1.64 | 0.237 | |||

| More than bachelor’s degree | 0.83 | 0.62-1.12 | 0.227 | |||

| Poor self-rated health | 0.80 | 0.66-0.96 | 0.017 | |||

| Easy to understand written doctor’s instructions | 0.83 | 0.68-1.02 | 0.077 | |||

| Easy to understand prescription instructions | 1.21 | 0.94-1.62 | 0.195 | |||

| Delayed care during previous year | 1.89 | 1.56-2.29 | < 0.001 | |||

| Insured during entire previous year | 0.51 | 0.37-0.70 | < 0.001 | |||

Abbreviations: CHIS, California Health Interview Survey; CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer; OR, odds ratio.

Sample included only those recommended for CRC screening during the previous 5 years. Current screening was defined as fecal occult blood test during previous year or sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy during the previous 5 years. Reference categories were K6 negative, male, age 50–65, non-Hispanic white, good self-rated health; difficult to understanding written doctor’s instructions; difficult to understand prescription instructions; uninsured at any point during the previous year; and less than high school.

Sensitivity Analysis

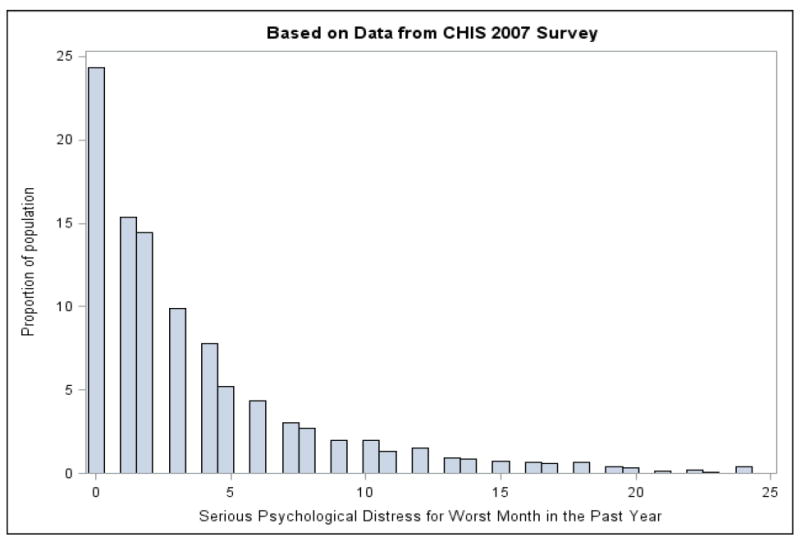

We also tested the association between higher levels of mental illness using different cutoff points on the Kessler K6 scale. These cutoff points were selected based on the distribution of the K6 in the study sample, depicted in Figure 2. The sensitivity analysis revealed similar trends using different cutoff scores. Thus, we do not report these results in detail.

Figure 2.

Histogram representing respondents’ K6 scores.

Factors Associated with CRC Screening Adherence in all CHIS Participants Age 50 or Older

We also evaluated whether mental illness was associated with CRC screening adherence in a post hoc analysis of all CHIS respondents age 50 or older. Six percent of this study population screened positive for mental illness, while 63% adhered to CRC screening. Among CHIS respondents age 50 and older, those who screened positive for a mental illness included a higher proportion of females (67% vs 53%; Rao-scott χ2 = 44.3; p<0.0001); persons age 50-65 (80% vs 63%; Rao-scott χ2= 133.7;p <0.0001); persons who have completed less than high school or less (77% vs 64%; Rao-scott χ2 = 50.1; p<0.0001); persons reporting poor self-rated health (58% vs 24%; Rao-scott χ2=323.4; p<0.0001); persons who reporting delaying care in the last year (34 vs 12%; Rao-scott χ2 = 211.9; p <0.0001); and persons who reported having insurance instability (15% vs 10%; Rao-scott χ2 = 19.69; p<0.0001). A lower proportion of individuals that screened positive for mental illness were non-Hispanic white (58% vs 61%; Rao-scott χ2 = 34.89; p<0.0001) and individuals reporting easy understanding prescription instructions (86.0% vs 90.2%; Rao-scott χ2 = 19.65; p<0.0001). Individuals who screened positive for mental illness were not recommended to get CRC screening at a rate that differed significantly from the general population. These descriptive results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of CHIS 2007 Respondents Age 50-85 (N = 30,266)

| Total | K6 positive | K6 negative | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 30,266) | (n = 1881) | (n = 28,385) | |||||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | Rao-Scott χ2 | df | P |

| Mental illness | |||||||||

| K6 positive | 1,881 | 6.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| K6 negative | 28,385 | 93.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CRC screening recommended in the last 5 years | 0.006 | 1 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Yes | 16,095 | 53.2 | 908 | 50.1 | 15122 | 50.0 | |||

| No | 14,171 | 46.8 | 973 | 49.7 | 13263 | 50.0 | |||

| CRC screening adherence | 3.50 | 1 | 0.062 | ||||||

| Adherent | 19,948 | 62.8 | 1126 | 59.0 | 18,822 | 63.1 | |||

| Nonadherent | 10,318 | 37.2 | 755 | 41.0 | 9,563 | 37.0 | |||

| Sex | 44.43 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Male | 11,753 | 46.3 | 541 | 32.7 | 11,212 | 47.2 | |||

| Female | 18,513 | 53.7 | 1340 | 67.3 | 17,173 | 52.8 | |||

| Age | 133.68 | 2 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 50–65 | 16,716 | 64.3 | 1,433 | 80.8 | 15,283 | 63.2 | |||

| 66–74 | 6,557 | 17.6 | 238 | 10.7 | 6,319 | 18.0 | |||

| 75–85 | 6,993 | 18.1 | 210 | 8.41 | 6,783 | 18.7 | |||

| Race and ethnicity | 34.89 | 4 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| non-Hispanic white | 22,644 | 60.7 | 1,289 | 57.7 | 21,355 | 60.9 | |||

| Hispanic | 3,198 | 19.8 | 2284 | 23.5 | 2,914 | 19.5 | |||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2,089 | 11.9 | 97 | 7.8 | 1,992 | 12.1 | |||

| Black | 1,350 | 5.5 | 94 | 5.8 | 1,256 | 5.5 | |||

| Other | 985 | 2.1 | 117 | 5.1 | 868 | 2.0 | |||

| Education | 50.08 | 3 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Less than high school | 2,781 | 16.9 | 310 | 24.4 | 2,471 | 16.4 | |||

| High school graduate | 15,439 | 48.4 | 1100 | 53.4 | 14,339 | 48.1 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 6,458 | 19.3 | 266 | 12.9 | 6,192 | 19.7 | |||

| More than bachelor’s degree | 5,588 | 15.4 | 205 | 9.3 | 5,383 | 15.7 | |||

| Self-rated health | 323.41 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Good | 23,382 | 74.0 | 830 | 41.7 | 22,552 | 76.1 | |||

| Poor | 6,884 | 26.0 | 1,051 | 58.3 | 5,833 | 23.9 | |||

| Understand prescription instructions | |||||||||

| Easy | 27,592 | 8.2 | 1,628 | 86.0 | 25,964 | 90.2 | 19.65 | 2 | <0.0001 |

| Difficult | 2,066 | 90.0 | 237 | 14.0 | 1,829 | 7.9 | |||

| Do not receive prescription instructions | 608 | 1.8 | 16 | .95 | 592 | 1.9 | |||

| Delayed care during previous year | 211.94 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Delayed | 4,171 | 13.5 | 672 | 34.4 | 3,499 | 12.1 | |||

| Not delayed | 26,095 | 86.5 | 1209 | 65.6 | 24,886 | 87.1 | |||

| Insurance status during previous year | 19.69 | 1 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Insured for entire year | 28,116 | 90.1 | 1616 | 85.2 | 26,500 | 90.4 | |||

| Uninsured at any point | 2,150 | 9.9 | 265 | 14.8 | 1,885 | 9.6 | |||

Abbreviations: CHIS, California Health Interview Survey; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Weighted to account for complex survey design and accurately represent California population. Weighted Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding error

Table 3 shows the results for the factors associated with CRC in our post-hoc study population. Comparison of factors from partially adjusted vs fully adjusted model show that the OR for having a mental illness was not significant in either model, (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.86-1.28 vs OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.63-1.25). In both the partially and fully adjusted models, factors that increased likelihood of CRC screening adherence included being age 66-74 vs 50-65 increased likelihood of screening adherence (OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.43-0.54 vs OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.49-0.62), as did being 75-85 vs 50-65 (OR, 0.45; 95%CI, 0.42-0.50 vs OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.48-0.58); and being Black (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.63-0.96 vs OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.62-0.96);

Risk factors for not adhering to CRC screening guidelines specific to the partially adjusted model included being Hispanic, relative to Non-Hispanic White (OR, 1.21; 95% CI,1.07-1.37); and being Asian or Pacific Islander (OR,1.17 95% CI,1.01-1.34).

Risk factors specific to the fully adjusted model included not having the experience of receiving prescription instructions (OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.77-3.34), delaying accessing health care for any reason (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.42-1.91). Factors that increased likelihood of screening adherence included having more than bachelor’s degree (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.83); having poor self-rated health (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.75-0.96); feeling that it is easy to understand written instructions from a doctor (OR, 0.79, 95%CI, 0.66-0.95) having insurance stability (OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.34-0.50), and having received a recommendation for screening during the previous 5 years (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.25-0.30). These results are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Adherence to CRC Screening among CHIS 2007 Respondents Age 50-85

| Partially Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| K6 positive | 1.05 | 0.86-1.28 | 0.597 | 0.95 | 0.77-1.17 | 0.640 |

| Female | 1.07 | 0.98-1.17 | 0.121 | 1.07 | 0.98-1.17 | 0.137 |

| Age | ||||||

| 66–74 | 0.48 | 0.43-0.54 | <0.0001 | 0.55 | 0.49-0.62 | < 0.001 |

| 75–85 | 0.45 | 0.42-0.50 | <0.0001 | 0.53 | 0.48-0.58 | < 0.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.21 | 1.07-1.37 | 0.0035 | 1.03 | 0.91-1.18 | 0.662 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.17 | 1.01-1.34 | 0.033 | 1.12 | 0.97-1.29 | 0.129 |

| Black | 0.79 | 0.63-0.96 | 0.0187 | 0.77 | 0.62-0.96 | 0.019 |

| Other | 1.21 | 0.94-1.56 | 0.1392 | 1.17 | 0.91-1.49 | 0.219 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school graduate | 0.86 | 0.74-1.00 | 0.056 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.87 | 0.73-1.04 | 0.115 | |||

| More than bachelor’s degree | 0.69 | 0.58-0.83 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Poor self-rated health | 0.85 | 0.75-0.96 | 0.009 | |||

| Easy to understand written doctor’s instructions | 0.79 | 0.66-0.95 | <0.001 | |||

| Do not receive written doctor’s instructions | 1.19 | 0.94-1.50 | 0.153 | |||

| Easy to understand prescription instructions | 0.95 | 0.78-1.17 | 0.630 | |||

| Do not receive prescription instructions | 2.42 | 1.77-3.34 | <0.001 | |||

| Delayed care during previous year | 1.65 | 1.42-1.91 | <0.001 | |||

| Insured during entire previous year | 0.41 | 0.34-0.50 | < 0.001 | |||

| Recommended for CRC Screening during previous 5 years | 0.27 | 0.25-0.30 | <0.001 | |||

Abbreviations: CHIS, California Health Interview Survey; CI, confidence interval; CRC, colorectal cancer; OR odds ratio.

Sample included all CHIS participants age 50 and older. Reference categories were K6 negative, male, age 50–65, non-Hispanic white, good self-rated health; difficult to understanding written doctor’s instructions; difficult to understand prescription instructions; uninsured at any point during the previous year; and less than high school.

Discussion

Improving access to preventive health care among adults with mental illness is a public health priority. The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the independent effect of having mental illness, defined using the K6,18 on the use of CRC screening services at the population level in California. We hypothesized that having a mental illness would increase risk for nonadherence to CRC screening services. Because our a priori analysis revealed that mental illness was not associated with adherence to CRC screening guidelines among survey respondents who had received a screening recommendation from their health care provider, we conducted a post hoc analysis to understand the independent effects of having mental illness on CRC screening adherence among all CHIS 2007 respondents age 50 or older. Our post hoc analysis also revealed no significant association between having mental illness and adherence to CRC screening guidelines.

These results are inconsistent with previous research, which has documented disparities in access to preventive services and cancer screening among adults with mental illness.13, 14 Further, our tables 1 and 3 revealed that, compared to those without mental illness, a higher proportion of those with mental illness have other risk factors that are known to impact utilization of health services including insurance instability, lower levels of education, and difficulty understanding instructions from their health care provider. Relevant to our analysis, a previous study reported on use of screening services among a clinical sample of adults with mental illness in one county in California. This study reported that only 50% of participants received CRC screening services at the recommended rate. Another study reported that having a mental illness decreased likelihood of adhering to CRC screening guidelines within the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs population.13 Results from the present study could differ from those of previous research due difference in composition of study population and sample. Consumers of public mental health services and consumers of VA services could face barriers to using cancer screening services that are less prevalent at the population level. Barriers could include the need to prioritize mental health diagnoses over preventive care, managing social comorbidities that often accompany mental illness, such as homelessness, along with and limited information related to cancer screening and follow up.

The present study’s use of data representative of California’s population could have also caused our results to differ from previous studies. For example, other research has reported that K6-defined mental illness is a risk factor for non-adherence to screening for other types of cancers using nationally representative data.26 Our results might differ from national trends due to state-specific differences in health care policy and service delivery. California’s Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) was implemented during 2005, which could have created a health services landscape for individuals with mental illness in California that differs from that of other states. This legislation prioritized improving the coordination of mental health services and implementing integrated physical and mental health care. The implementation of the MHSA could have affected the relationship between mental illness and colorectal cancer screening in our study. Future studies should examine this relationship in different policy environments that might exist in other states.

Although we did not find support for our study hypotheses, our analyses revealed other factors associated with nonadherence to CRC screening guidelines, including being female who have received a screening recommendation, being between 50 and 65 years old, delaying health one’s care, and insurance instability. These findings are consistent with prior literature 27 and suggest a need for enhanced outreach among members of these study subgroups. Poor self-rated health was associated with increased odds of screening adherence, which could indicate a perceived need for health care services, including cancer screening.

Our post hoc analysis revealed that having low health literacy was an additional risk factor for CRC screening nonadherence. Specifically, having difficulty understanding written instructions from a doctor and never receiving prescription instructions were risk-factors for non-adherence. Our post hoc analysis also revealed that having a college degree or higher increased likelihood of screening adherence. Taken together, these findings support previous work17 suggesting the need for enhanced outreach by health care providers for patients with lower levels of health literacy and education to increase adherence to CRC screening guidelines.

Finally, post hoc analyses also revealed that self-identifying as Black or African American was associated with increased odds to adhering to CRC screening recommendations. The American College of Gastroenterology17 has specified that CRC screening for black men and women should begin at age 45, compared to age 50 among other racial groups. This finding could indicate that targeted outreach among black individuals is occurring in California.

Limitations and Strengths

Random-digit-dialing surveys have inherent limitations. Self-reported data could lead to overestimation of use of CRC screening services and to other inaccuracies in survey responses. It is also possible that CRC screening adherence varies by type of mental illness. The K6 is a reliable metric for assessing mental illness and functioning, but does not diagnose specific psychiatric disorders. Therefore, our approach precluded us from understanding whether CRC screening adherence varies by psychiatric diagnosis. Further, even though the K6 has yielded national and state-level estimates of serious mental illness which have informed the funding of block grants for community mental health services, it is used to screen for serious mental illness within the past 12 months. This fact introduces the issue of time ordering with our dependent variable, which assesses for CRC screening within the last five years. It is possible that individuals who screened positive for mental illness had received a recommendation for CRC screening before they began experiencing symptoms. Another potential limitation is the possibility of selection bias. It is possible that persons with the most serious mental illness did not complete this survey, which could have distorted the extent to which persons with serious mental illness adhere to CRC screening guidelines. Further, the CHIS does not include homeless individuals, who are at increased risk for a range of mental and physical health vulnerabilities and experience limited access to primary and preventive services. The nature of secondary data analysis also limited which variables we were able to include in our statistical models. The 2007 CHIS did not allow us to examine whether respondents were receiving mental health services, which could influence use of other types of health care such as CRC screening. Finally, these results might not be generalizable to the U.S. population.

However this study has a number of strengths. Our study is among the first few to investigate the association between having serious psychological distress and adherence to CRC screening services using a population-based approach. Our weighted statistical models were theoretically informed and adjusted for known risk and protective factors related to accessing cancer-screening services.

Conclusion

Because of the high mortality associated with colon cancer, understanding disparities in access to cancer screening services is an important topic that warrants further research. To achieve an enhanced understanding of CRC screening adherence among adults with mental illness, future studies should investigate the relationship between mental illness and CRC screening adherence using nationally representative data. Because state-specific health care policies could influence use of CRC services among individuals with mental illness, future studies should also evaluate the comparative effectiveness of population-based interventions designed to reduce a broad spectrum of health disparities, including disparities in screening adherence. The Affordable Care Act is an example of an initiative that provides states with some autonomy to tailor their health service delivery systems. This legislation could provide an ideal opportunity to understand how these policies affect disparities in cancer screening by psychiatric diagnosis over time. This could be accomplished through analysis of administrative data from mental health systems that document both psychiatric diagnosis and use of CRC screening services.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Cecilia Patino-Sutton and Dr. Jonathan Samet for their guidance in the development of this manuscript.

Funding Source: At the time of the research, Drs. Siantz and Wu were TL1 Scholars and Drs. Shiroshi and Idos are KL2 Scholars awarded through Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute at the University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine. The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through Grant Awards TL1TR000132 and KL2TR000131. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH

References

- 1.Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics 2001. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:15–36. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender R, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:38–75. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:389–394. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. Cancer screening in the United States 2007 a review of current guidelines, practices, and prospects. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:90–104. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klabunde CN, Vernon SW, Nadel MR, Breen N, Seeff LC, Brown ML. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med Care. 2005;43:939–944. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173599.67470.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, Morrato EH, Marcus SC. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49:599–604. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820bf86e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Druss BG. The mental health/primary care interface in the United States: history, structure, and context. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leigh H, Stewart D, Mallios R. Mental health and psychiatry training in primary care residency programs: part II. what skills and diagnoses are taught, how adequate, and what affects training directors’ satisfaction? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berren MR, Santiago JM, Zent MR, Carbone CP. Health care utilization by persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:559–561. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ionescu-Ittu R, McCusker J, Ciampi A, et al. Continuity of primary care and emergency department utilization among elderly people. CMAJ. 2007;20(177):1362–1368. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard LM, Barley EA, Davies E, et al. Cancer diagnosis in people with severe mental illness: practical and ethical issues. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:797–804. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kodl MM, Powell AA, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Bangerter AK, Partin MR. Mental health, frequency of healthcare visits, and colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2010;48:934–939. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e57901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong GL, Bermudes RA, Torres SN, Hales RE. Use of cancer-screening services among persons with serious mental illness in Sacramento County. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:929–932. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.8.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1334–1349. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. [April 27, 2015];California Health Interview Survey: methodology briefs, papers, and reports. http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Pages/methodology.aspx. Updated 2012.

- 17.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–350. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Croft JB, Mokdad AH, Power AK, Greenlund KJ, Giles WH. Public health surveillance of serious psychological distress in the United States. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(suppl 1):4–6. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandelblatt JS, Yabroff KR, Kerner JF. Equitable access to cancer services: a review of barriers to quality care. Cancer. 1999;86:2378–2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen R. A Behavioral Model of Families’ Use of Health Services. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, Center for Health Administration Studies; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aday LA, Andersen RM, Fleming GV. Health Care in the US: Equitable for Whom? Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sentell T, Braun KL, Davis J, Davis T. Colorectal cancer screening: low health literacy and limited English proficiency among Asians and whites in California. J Health Commun. 2013;18(suppl 1):242–255. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SPSS Inc. Released 2009. PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 25.SAS Institute Inc. SAS Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.,; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiang X. Serious psychological distress as a barrier to cancer screening among women. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxwell AE, Crespi CM. Trends in colorectal cancer screening utilization among ethnic groups in California: are we closing the gap? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:752–759. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]