Abstract

Duodenal phytobezoar, an unusual cause of acute duodenal obstruction, is rarely seen. The most common cause of this type of bezoar is persimmon. It frequently arises from underlying gastrointestinal tract pathologies (gastric surgery, etc.). Here, we report the case of a 66-year-old man who had undergone distal gastrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction for gastric cancer and experienced severe epigastric discomfort, abdominal pain, and vomiting for a few days. The abdominal computed tomography scan showed a large-sized mass in the horizontal portion of the duodenum. On following endoscopic examination, a large phytobezoar was revealed in the duodenum. He was treated with endoscopic fragmentation combined with nasogastric Coca-Cola. The patient tolerated the procedure well and resumed a normal oral diet 3 days later.

Keywords: Coca-Cola, Duodenal obstruction, Endoscopic fragmentation, Persimmon phytobezoar

Introduction

Phytobezoars, resulted from ingestion of vegetable and plant material of certain types, are indigestible masses trapped in the gastrointestinal tract [1]. The most common cause of this type of bezoar is persimmon, which is very popular in many Asians countries [2]. Patients with persimmon phytobezoar may experience epigastric discomfort, abdominal pain, vomiting, and in severe cases, gastric ulceration, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and perforation [3]. Large phytobezoars are generally retained in the stomach. However, they may occur in the duodenum in patients who have undergone gastric surgery. Primarily, a duodenal obstruction because of a phytobezoar is rarely seen. Although the reported incidence is less than 0.4 % in the general population, phytobezoar may be associated with a high mortality [4]. Therefore, it is very important to remove the bezoar in order to prevent further complications. Clinically, persimmon phytobezoars are often resistant to the medication and, hence, they are usually removed endoscopically or surgically. Recently, combined therapy of endoscopic fragmentation and nasogastric Coca-Cola has been used as efficient methods to dissolve phytobezoars in some patients [5]. Here, we report the case of a large duodenal phytobezoar in a 66-year-old man who presented with duodenal obstructive symptoms and was successfully treated with endoscopic fragmentation combined with nasogastric Coca-Cola.

Case Report

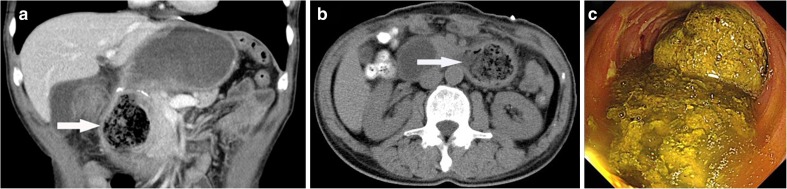

In this report, we draw special attention to a 66-year-old man with a large duodenal persimmon phytobezoar after distal gastrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction for gastric cancer. However, he complained of intermittent epigastric discomfort, acid regurgitation, and occasional vomiting with green grass gastric contents after eating dried persimmon on May 2, 2015. His symptoms greatly improved after vomiting, so he made nothing of the illness. On May 5, 2014, he was referred to our hospital due to his aggravated epigastric distention. On admission, his vital signs were stable with a blood pressure of 128/76 mmHg and a heart rate of 83 beats/min and chest and cardiac findings were unremarkable. The abdomen was supple without masses or organomegaly, and the abdominal sounds were normal, but there was moderate epigastric tenderness. On examination, the abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a well-defined, oval, non-homogeneous mass in the horizontal portion of the duodenum (Fig. 1a, b). The following esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed lots of dark green gastric juice stored in the gastric remnant, slightly hyperemic gastric mucosa, mild gastroduodenal anastomoses hyperemia erosion, and a very huge phytobezoar with a regular surface in the duodenum which caused local obstruction (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

a, b CT scan showing a well-defined, oval, non-homogeneous mass in the horizontal portion of the duodenum (white arrow). c EGD examination revealed dark green gastric juice stored in the gastric remnant and a very huge bezoar with a regular surface in the horizontal portion of the duodenum

He was first treated with nasogastric tube intubation, intravenous fluid, and proton pump inhibitors after a presumptive diagnosis of duodenal obstruction caused by a persimmon phytobezoar. Initially, we tried to endoscopically remove the phytobezoar, but this was unsuccessful because the surface layer of the persimmon phytobezoar was too hard to break through with endoscopy forceps (FG-47L-1; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Then, we decided to attempt administering two cans (500 mL) of Coca-Cola (Coca-Cola Co., Hangzhou, China) every 6 h according to the method described elsewhere [6]. Two days later, EGD demonstrated that the persimmon phytobezoar was much softened and it was smaller than previously noted. We performed direct endoscopic injection of Coca-Cola into the persimmon phytobezoar. However, 4 days passed, the persimmon phytobezoar was still in the duodenum. An endoscopic injection of Coca-Cola was tried again. Five days later, we fragmented the persimmon phytobezoar by endoscopic forceps and polypectomy snares (MTW Endoskopie, Wesel, Germany) and then removed the fragments by a retrieval net device (MTW Endoskopie, Wesel, Germany) until the persimmon phytobezoar was broke into pieces (Fig. 2a–c). After the treatment, the patient could have some liquid diet and he gradually was able to eat properly. The third day after the treatment, he resumed a normal oral diet and was discharged home.

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic images of the process of fragmenting the persimmon phytobezoar by endoscopic forceps

The EGD was repeated 1 week later and revealed that the persimmon phytobezoar had disappeared, and no residual phytobezoar was seen. Since his discharge, he has had no subsequent symptoms of abdominal pain or vomiting. At the 1-month follow-up, no recurrence of a phytobezoar was noted.

Discussion

Bezoars are classified according to their content into phytobezoars, trichobezoars, lactobezoars, mixed-medication bezoars, and food bolus bezoars. Phytobezoars, the most common type of bezoars, are composed of indigestible cellulose, tannin, and lignin derived from ingested vegetables and fruits [7]. Duodenal phytobezoars are extremely rare and often originate in the stomach due to the presence of the pyloric sphincter. A gastric phytobezoar may pass down to the duodenum and cause a duodenal obstruction. Although it is a rare occurrence in clinics, it has been recognized that the formation of persimmon phytobezoar is a common complication that occurs after gastric operation. In our patient, risk factors were distal gastrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction and overindulgence of persimmons.

Clinical manifestations of persimmon phytobezoar vary from no symptoms to acute abdominal distress including dyspepsia, abdominal pain, and vomiting or nausea. CT scanning and endoscopic investigations can show and confirm almost all duodenal phytobezoars [8]. In our case, CT scanning showed a well-defined, oval, non-homogeneous mass in the horizontal portion of the duodenum, which was also confirmed by EGD.

Phytobezoars can be treated in several ways including pharmacologic dissolution, endoscopic procedure, and surgical treatment; however, there is no consensus regarding the management. Due to complications and operative trauma, surgical treatment for duodenal phytobezoar is rarely necessary. To date, there have been several reports describing the clinical utility of administering Coca-Cola to dissolve phytobezoars. The first successful treatment outcomes achieved with Coca-Cola lavage were reported in 2002 by Ladas et al., who treated five gastric phytobezoar patients [5]. As a carbonated soft drink, Coca-Cola-caused dissolution may be associated with a change of pH and penetration of CO2. It has been suggested that the NaHCO3 contained in Coca-Cola has a mucolytic effect. Persimmon phytobezoar, because of its particular features, should be considered separately from other phytobezoars, especially as far as treatment is concerned. The almost stony consistency of these phytobezoars renders the nonoperative treatments used for other phytobezoars ineffective. Because of persimmon phytobezoars’ hard consistency, a single endoscopic fragmentation or dissolution therapy is difficult and sometimes cannot be successful used. In our case, we initially tried to endoscopically remove the phytobezoar but this was not possible because the phytobezoar was very hard and removal could cause bowel perforation. Two liters of Coca-Cola a day combined with endoscopic fragmentation for 4 days was prescribed to the patient, which could diminish the size and soften the consistency of the phytobezoar. On day 5, we successfully treated the large duodenal persimmon phytobezoar by using a combination of endoscopic fragmentation and Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola administration is a cheap and easy to perform procedure that can be accomplished at any endoscopy unit. Moreover, endoscopic fragmentation is more efficacious in breaking the phytobezoar and that the combination of Coca-Cola and endoscopic fragmentation is better in dissolving the phytobezoar.

In conclusion, we report here on a case of duodenal obstruction caused by a persimmon phytobezoar after distal gastrectomy. It is an extremely rare event in which the persimmon phytobezoar was located in the horizontal portion of the duodenum, and the surgical treatment is relatively difficult. This case shows the safety and feasibility of a combined therapy of nasogastric Coca-Cola and endoscopic fragmentation in the patient with a large duodenal persimmon phytobezoar, which also shortens patient hospitalization and minimizes operative trauma. However, we hope to raise concern among gastroenterologists regarding this matter, although rare.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication.

References

- 1.Raveenthiran V. An unusual association of gastroduodenal phytobezoar and malrotation of the midgut. Indian J Surg. 2009;71(1):38–40. doi: 10.1007/s12262-009-0009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwamuro M, Urata H, Furutani M, et al. Ultrastructural analysis of a gastric persimmon phytobezoar. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38(4):e85–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pergel A, Yucel AF, Aydin I, Sahin DA. Laparoscopic treatment of a phytobezoar in the duodenal diverticulum—report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3(8):392–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKechnie JC. Gastroscopic removal of a phytobezoar. Gastroenterology. 1972;62(5):1047–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladas SD, Kamberoglou D, Karamanolis G, Vlachogiannakos J, Zouboulis-Vafiadis I. Systematic review: Coca-Cola can effectively dissolve gastric phytobezoars as a first-line treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(2):169–173. doi: 10.1111/apt.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung YW, Han DS, Park YK, et al. Huge gastric diospyrobezoars successfully treated by oral intake and endoscopic injection of Coca-Cola. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38(7):515–517. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benharroch D, Krugliak P, Porath A, Zurgil E, Niv Y. Pathogenetic aspects of persimmon bezoars. A case-control retrospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17(2):149–152. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199309000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KH, Han HY, Kim HJ, Kim HK, Lee MS. Ultrasonographic differentiation of bezoar from feces in small bowel obstruction. Ultrasonography. 2015;34(3):211–216. doi: 10.14366/usg.14070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]