Abstract

Background

Because eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) causes dysphagia, esophageal narrowing, and strictures, it could result in low body mass index (BMI), but there are few data assessing this.

Aim

To determine whether EoE is associated with decreased BMI.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study at the University of North Carolina from 2009–2013 enrolling consecutive adults undergoing outpatient EGD. BMI and endoscopic findings were recorded. Incident cases of EoE were diagnosed per consensus guidelines. Controls had either reflux or dysphagia, but not EoE. BMI was compared between cases and controls and by endoscopic features.

Results

Of 120 EoE cases and 297 controls analyzed, the median BMI was lower in EoE cases (25 kg/m2 vs. 28 kg/m2, p=0.002). BMI did not differ by stricture presence (26 kg/m2 vs. 26 kg/m2, p=0.05) or by performance of dilation (26 kg/m2 vs. 27 for undilated; p=0.16). However, BMI was lower in patients with narrow caliber esophagus (24 kg/m2 vs. 27, p<0.001). EoE patients with narrow caliber esophagus also had decreased BMI compared to controls with narrow caliber esophagi (24 kg/m2 vs. 27, p=0.001). On linear regression after adjustment for age, race, and gender, narrowing decreased BMI by 2.3 kg/m2 [95% CI −4.1, −0.6].

Conclusions

BMI is lower in EoE cases compared to controls, and esophageal narrowing, but not focal stricture, is associated with a lower BMI in patients with EoE. Weight loss or low BMI in a patient suspected of having EoE should raise concern for esophageal remodeling causing narrow caliber esophagus.

Keywords: eosinophilic esophagitis, body mass index, stricture, narrowing, dilation

Introduction

Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE) is a condition of chronic immune-mediated inflammation of the esophagus characterized by dysphagia and other symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and the presence of eosinophils on tissue evaluation [1–3]. Given the structural remodeling of the esophagus such as narrowing, strictures, and rings that occurs in EoE as a consequence of chronic inflammation [4–10], there is concern EoE could decrease oral intake, resulting in weight loss and malnutrition. Indeed, in infants and children, poor growth and feeding intolerance are common symptoms of EoE [11–14], but this has not been examined in detail in adults.

To date, research on BMI in EoE patients at the time of diagnosis has been sparse. As dysphagia is the most commonly reported symptom in adolescents and adults with EoE [1–3,15–18], it is not surprising that many patients will modify their diet and their eating habits by avoiding foods that stick, eating slowly, and chewing thoroughly [19,20]. However, the impact of symptoms and these avoidance/modification behaviors on BMI are not known. It is also not known if a low BMI is more common at diagnosis in EoE or if features of EoE correlate with BMI.

The aim of this study was to assess whether incident EoE is associated with a decreased BMI. Additionally, we aimed to determine if specific clinical and endoscopic features of EoE were associated with decreased BMI. We hypothesized that EoE patients would have diminished BMI compared to non-EoE controls and that the decrease in BMI would be of greater magnitude in the presence of structural remodeling of the esophagus (i.e rings, strictures, narrow esophageal caliber).

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study at the University of North Carolina from 2009 to 2013. Details of the protocol have been previously reported [21–24]. In brief, consecutive adult patients (age 18–80 years) undergoing routine outpatient esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were approached if they had symptoms suggestive of esophageal dysfunction (e.g., dysphagia, food impaction, heartburn, reflux, chest pain). Subjects provided informed consent and were enrolled before the endoscopy. Subjects were excluded if they had a known (prevalent) diagnosis of EoE or other eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder, gastrointestinal bleeding, active anticoagulation, known esophageal cancer, prior esophageal surgery, known esophageal varices, medical instability or comorbidities precluding enrollment in the opinion of the endoscopist, or an inability to read or understand the consent form. This study was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board.

Cases were diagnosed with incident EoE if they met consensus guidelines [1–3]. Specifically, they were required to have at least one typical symptom of esophageal dysfunction; at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) on esophageal biopsy persisting after an 8-week PPI trial (20–40 mg twice daily of any of the available agents, prescribed at the discretion of the clinician); and other causes of esophageal eosinophilia excluded. Of note, these were incident EoE cases, such that case/control status could not be definitively assigned until after the PPI trial and repeat EGD. Controls were subjects who, after endoscopy and biopsy, did not meet the clinical or histologic criteria for EoE. Controls were further subdivided based on their chief presenting symptom into dysphagia controls and reflux controls. Subjects with PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia were not included in the present analysis.

Clinical data were collected using a standardized case report form. Items recorded included demographics, anthropomorphic features (height and weight for calculation of BMI), symptoms, concomitant atopic diseases, indications for endoscopy, and endoscopic findings. Of note, strictures were defined as a focal area of reduced luminal diameter in the esophagus of any length with adjoined esophagus of normal caliber, while narrowing was defined as a diffuse decrease in luminal diameter throughout the course of the esophagus. During endoscopy, five research-protocol esophageal biopsies were obtained (two from the proximal, one from the mid, and two from the distal esophagus) to maximize EoE diagnostic sensitivity [25,26]. Gastric and duodenal biopsies were also collected for research purposes to exclude concomitant eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Esophageal eosinophil counts were quantified by the study pathologists using our previously validated methods [27]. Briefly, slides were masked to case/control status, digitized, and reviewed with Aperio ImageScope (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA). Five microscopy fields from each of the five biopsies were examined to determine the maximum eosinophil density (eosinophils/mm2 [eos/mm2]). So histologic results could be compared with prior studies, eosinophils density was standardized to a high powered field (hpf) of 0.24 mm2 and reported as eosinophils per hpf (eos/hpf) [12].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline clinical, endoscopic, and histologic characteristics of the cases and controls. Non-parametric testing (Wilcoxon signed rank) was used to compare medians, as all continuous variables of interest were non-normally distributed. Proportions were compared with χ2 testing. BMI was compared between EoE cases and controls (both reflux and dysphagia controls) as well as among EoE cases and controls with endoscopic features likely to impair swallowing (e.g. narrowing, strictures, dilation). BMI values were stratified into 4 ranges corresponding with standard medical definitions of weight: <18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 (normal weight), 25–29.9 kg/m2 (overweight), and ≥30 kg/m2 (obese). Logistic regression models were constructed to assess the odds of obesity in patients based on their clinical features, while controlling for potentially confounding variables. Generalized linear models were constructed to analyze the change in BMI caused by the presence of selected endoscopic features.

Results

A total of 120 EoE cases and 297 controls were included. Compared with controls, EoE patients were more likely to be younger (median 37 years old vs. 55; p<0.0001), male (63% vs. 38%; p<0.0001), white (93% vs. 79%; p=0.0003), and have an atopic disorder (70% vs. 60%; p=0.046). (Table 1) Endoscopic findings typical of EoE were more common in the EoE group. For example, EoE cases were more likely to have strictures (28% vs 19%; p=0.03), rings (82% vs. 13%; p<0.0001), or esophageal narrowing (34% vs. 4%; p<0.0001). Most patients with narrowing (31 of 54, 57%) received dilation, and EoE patients with narrowing underwent fewer dilations than controls with narrowing (49% vs 85%, p = 0.02). Patients with stricture were also likely to receive dilation (77 of 89, 87%), and EoE patients with strictures were underwent fewer dilations than controls with strictures (74% vs 95%, p = 0.005). The median peak eosinophil count at diagnosis was 104 (interquartile range (IQR) 124) eos/hpf in EoE cases compared with 0 (IQR 2) eos/hpf among controls (p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Controls (n = 297) | EoE Cases (n = 120) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 55 (22) | 37 (15) | <0.0001 |

| White Race, n (%) | 234 (79) | 112 (93) | 0.0003 |

| Male Gender, n (%) | 112 (38) | 75 (63) | <0.0001 |

| Any atopic Disease, n (%) | 163 (60) | 83 (70) | 0.046 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 70 (26) | 33 (28) | 0.68 |

| Eczema, n (%) | 22 (8) | 9 (8) | 0.87 |

| Seasonal allergy, n (%) | 136 (50) | 74 (63) | 0.02 |

| Food allergy, n (%) | 44 (16) | 43 (36) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline EGD Findings, n (%) | |||

| Normal | 59 (20) | 3 (3) | <0.0001 |

| Rings | 37 (13) | 98 (82) | <0.0001 |

| Stricture | 55 (19) | 34 (28) | 0.03 |

| Narrowing | 13 (4) | 41 (34) | <0.0001 |

| Furrows | 19 (6) | 104 (87) | <0.0001 |

| Crepe paper | 3 (1) | 9 (8) | 0.0003 |

| White plaques | 13 (4) | 55 (46) | <0.0001 |

| Decreased vascularity | 9 (3) | 60 (50) | <0.0001 |

| Hiatal hernia | 125 (42) | 18 (15) | <0.0001 |

| Dilation | 95 (32) | 39 (33) | 0.92 |

| Baseline peak eosinophil count (eos/hpf), median (IQR) | 0 (2) | 104 (124) | <0.0001 |

p values presented are the result of Wilcoxon signed rank testing of continuous variables or χ2 testing of categorical variables.

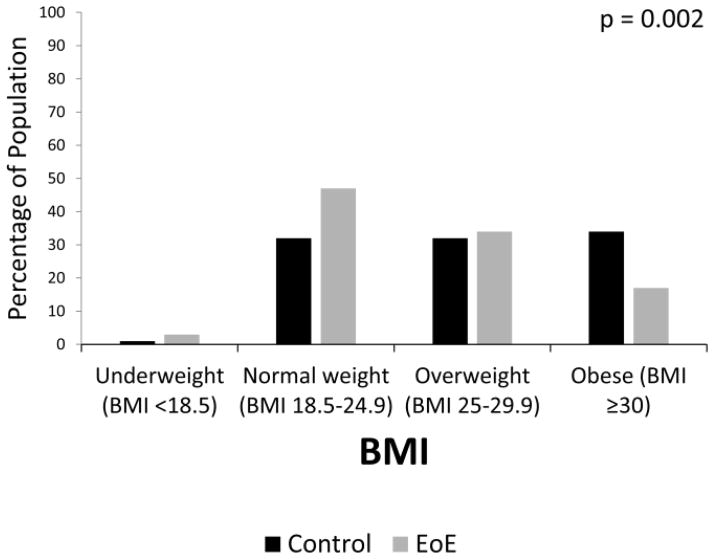

The median BMI was lower among EoE patients than controls (25 kg/m2, IQR 5 vs. 28 kg/m2, IQR 8; p=0.002). The distribution of patients among BMI categories was shifted downward in EoE cases with 17% obese compared to 34% of controls, and 47% normal weight compared to 32% of controls (Figure 1). This relationship persisted after adjusting for age, race and gender (OR for obesity in EoE patients = 0.54 [0.30–0.99]). The dysphagia controls and reflux controls did not differ on median BMI (27 kg/m2, IQR 8 vs 28 kg/m2, IQR 9; p=0.07) or on the distribution of BMI categories. (Table 2) The median BMI among EoE cases differed significantly from reflux controls (p< 0.0001) and dysphagia controls (p=0.007). The distribution of BMI categories differed significantly between EoE cases and reflux controls, but did not reach significance when comparing EoE cases to dysphagia controls (Table 2).

Figure 1.

BMI distribution in EoE cases and non-EoE controls. P value represents the comparison of weight categories between groups.

Table 2.

BMI in EoE vs Control Subgroups

| EoE n = 120 |

Dysphagia Controls n = 177 |

Reflux Controls n = 120 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (< 18.5 kg/m2) | 3 (3) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 56 (47) | 61 (34) | 35 (29) |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 41 (34) | 60 (34) | 36 (30) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 20 (17) | 52 (29) | 49 (41) |

| p-value* | -- | 0.06 | 0.0001 |

compared to EoE group. P-value comparing dysphagia controls to reflux controls = 0.09.

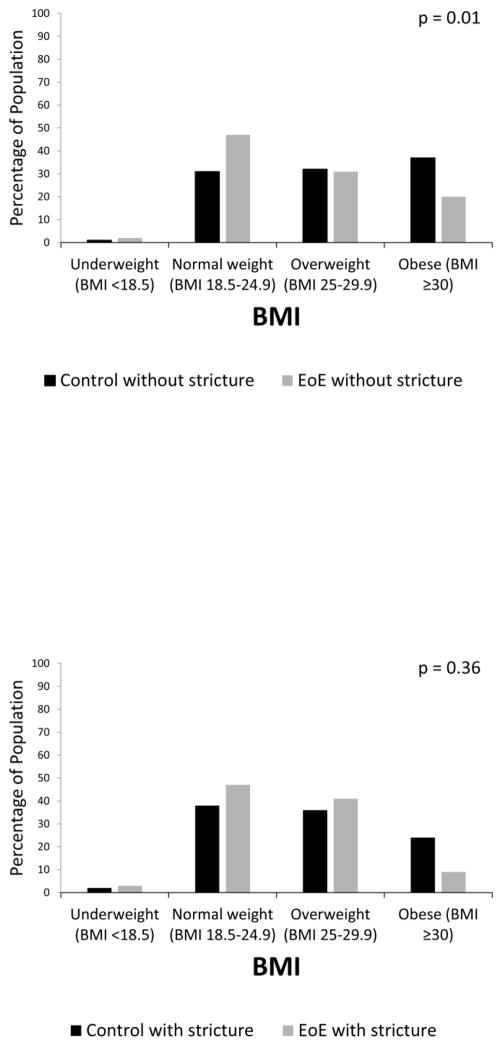

The presence of a stricture at baseline did not impact BMI in the total study population (median BMI with stricture 26 kg/m2, IQR 7 vs. 26 kg/m2, IQR 8 without stricture; p=0.05). EoE patients without strictures had a lower median BMI compared to controls without strictures (25 kg/m2, IQR 5 vs. 27 kg/m2, IQR 8; p=0.001), and were less likely to be obese (20% vs 37%) and more likely to be normal weight (47% vs 31%; p = 0.001) (Figure 2a). The pattern was similar among EoE patients with strictures compared to controls with strictures, but did not reach statistical significance (median BMI 25 kg/m2, IQR 6 vs. 27 kg/m2, IQR 7; p=0.07; 9% obese vs 24% and 47% normal weight vs 38%, p = 0.36) (Figure 2b). On linear regression after adjustment for age, race, and gender, the presence of a stricture at baseline did not significantly impact BMI in the population as a whole (−1.0 kg/m2 [95% CI −2.5, 0.4]) or in patients with EoE (−0.7 kg/m2 [95% CI −2.6, 1.2]).

Figure 2.

(A) BMI distribution in EoE cases without strictures and non-EoE controls without strictures. (B) BMI distribution in EoE cases with strictures and non-EoE controls with strictures. P values represent the comparison of weight categories between groups.

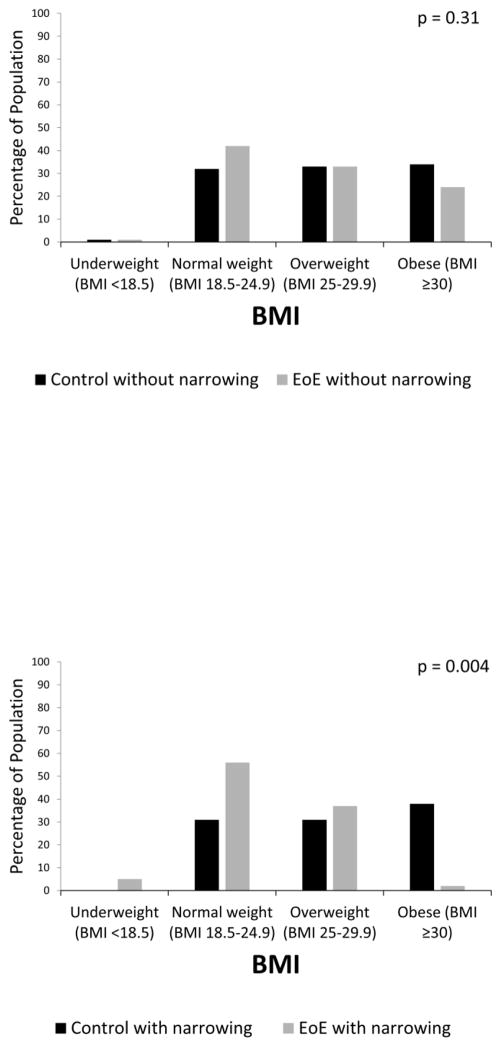

The presence of esophageal narrowing reduced BMI in the total study population (median BMI with narrowing 24 kg/m2, IQR 5 vs. 27 kg/m2, IQR 8 without; p=0.0002). The median BMI in EoE patients without narrowing did not differ statistically from controls without narrowing (26 kg/m2, IQR 7 vs. 27 kg/m2, IQR 8; p=0.07). There was no statistical difference in the frequency of obesity (24% vs 34%) or normal weight (42% vs 32%; p = 0.31) (Figure 3a). However, among patients with narrowing, EoE patients had a lower median BMI than controls with narrowing (24 kg/m2, IQR 5 vs. 27 kg/m2, IQR 5; p=0.001). EoE patients with esophageal narrowing were less likely to be obese (2% vs 38%) and more likely to be normal weight (56% vs 31%, p = 0.004) (Figure 3b). On linear regression after adjustment for age, race, and gender, the presence of narrowing at baseline significantly decreased the BMI in the population as a whole (−2.3 kg/m2 [95% CI −4.1, −0.6]) and in patients with EoE (−2.6 kg/m2 [95% CI −4.3, −0.8]).

Figure 3.

(A) BMI distribution in EoE cases without narrowing and non-EoE controls without narrowing. (B) BMI distribution in EoE cases with narrowing and non-EoE controls with narrowing. P values represent the comparison of weight categories between groups.

Discussion

EoE is associated with dysphagia and endoscopic abnormalities such as esophageal strictures and narrowing, particularly in adolescents and adults. However, little is known about the association of these features with BMI. In this prospective study that collected clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and anthropomorphic data on incident cases of EoE and non-EoE controls, we evaluated differences in BMI and the impact of endoscopic fibrotic changes on BMI. We found that EoE patients have a lower BMI than non-EoE controls, both when BMI is viewed as a continuous variable and when categorized into standard ranges from underweight to obese. On further examination of the esophageal characteristics most likely to produce reduced BMI, we found that the presence of esophageal strictures did not impact BMI, but narrowing reduced BMI by more than 2 kg/m2 regardless of EoE status. However, unlike strictures, which were present in about 20% of our controls, narrowing is more specific to EoE with one-third of EoE patients having a narrowed esophagus while only 4% of non-EoE controls demonstrated this finding. This may indicate that lower BMI in EoE patients should raise clinical suspicion for esophageal narrowing. However, a low BMI, by itself, is not specific enough to aid in the diagnosis of EoE.

While weight loss is a common symptom in gastrointestinal conditions and failure to thrive, poor growth, or feeding intolerance can be symptoms of EoE in infants and young children [11–14], a paucity of data exists on BMI in EoE. Liacouras and colleagues found that out of 247 children enrolled in a study evaluating elimination diet to treat EoE, only 5 had weights < 5th percentile on the appropriate growth curve [13]. Von Arnim and colleagues evaluated for clinical markers of EoE in a retrospective study involving 43 adults and similarly found no significant difference in weight loss between EoE and GERD patients. However, only 4 patients (1 with EoE) reported weight loss [28]. More recently, a low BMI has been identified in patients with concomitant EoE and connective tissue disease [29], and a higher BMI has been associated with EoE patients who are vitamin deficient [30]. We were unable to find any studies assessing BMI in EoE cases and controls, stratified by endoscopic fibrotic findings, that would be directly comparable to our results.

When interpreting data from this study, there are potential limitations to consider. Because reflux is associated with obesity and is a common cause of dysphagia, patients referred for dysphagia which was not caused by EoE may be more likely to be obese. This may elevate the BMI of the non-EoE controls relative to the general population, though the data here are still representative of a group of patients referred for endoscopy. In addition, the study was performed at a single center and did not include children, so results cannot be generalized to pediatric populations. Heights and weights were self-reported by the participant. However, potential bias stemming from self-reporting would presumably be similar in both case and control groups, especially among groups with like symptoms, such as the dysphagia control group. Our endoscopic measures of fibrosis (stricture and narrowing) were recorded as per endoscopist report, and we do not have data on severity of stricture or length of narrowing, and this may introduce heterogeneity into these categories. Finally, as this study was a cross-sectional analysis, we do not have outcomes data on whether successful treatment of EoE caused a change in BMI.

Our study also has a number of strengths. The study was prospective and focused on a population of well-characterized incident EoE cases and non-EoE controls. All patients were evaluated at the time of initial presentation, meaning that the comparison of BMI between cases and controls could not be confounded by therapy directed at EoE. It is the only study to date to specifically evaluate BMI between EoE and non-EoE controls and to examine the role of endoscopic fibrotic features on BMI. Uniform methods were used for case-control identification, baseline data collection, and endoscopic evaluation, and these data were collected before EoE diagnosis was known.

In conclusion, in this large prospective study, EoE case status was associated with decreased BMI compared with controls. However, BMI for most EoE patients was not in the underweight range, and a low BMI was not specific enough to be helpful for diagnosis of EoE. Esophageal narrowing may drive decreased BMI, and weight loss or low BMI in a patient suspected of having EoE should raise concern for esophageal remodeling causing narrow caliber esophagus. Evaluation in this setting should include barium swallow which has previously been shown to be a sensitive test for esophageal narrowing in EoE [31,32]. Further research should assess whether treatment of EoE and resolution of esophageal narrowing cause changes to BMI.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This research was funded by T32 DK07634 (WAW; TMR; SE), K23DK090073 (ESD), K24DK100548 (NJS), and R01DK101856 (ESD) from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- eos

eosinophils

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- hpf

high powered field

- IQR

interquartile range

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Specific author contributions (note that all authors approved final version):

Wolf: Manuscript drafting; data analysis/interpretation; critical revision

Piazza: Manuscript drafting; critical revision

Gebhart: Patient recruitment; data collection and management; critical revision

Rusin: Data collection/pathology interpretation; critical revision

Covey: Data collection/pathology interpretation; critical revision

Higgins: Patient recruitment; data collection and management; critical revision

Beitia: Patient recruitment; data collection and management; critical revision

Speck: Data collection/pathology interpretation; critical revision

Woodward: Data collection/pathology interpretation; critical revision

Cotton: Data analysis/interpretation; critical revision

Runge: Data collection; critical revision

Eluri: Data collection; critical revision

Woosley: Pathology supervision; critical revision

Shaheen: Supervisions; data interpretation; critical revision

Dellon: Project conception; supervision; data analysis/interpretation; critical revision.

Relevant Financial Disclosures: None of the authors have potential conflicts related to this manuscript. Dr. Dellon receives research funding from Meritage, Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire, and is a consultant for Adare, Banner, Receptos, Regeneron, and Roche.

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679–692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. quiz 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. quiz 21–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng E, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Tissue remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1175–1187. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00313.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eluri S, Runge TM, Cotton CC, et al. The extremely narrow-caliber esophagus is a treatment-resistant subphenotype of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1142–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirano I, Aceves SS. Clinical implications and pathogenesis of esophageal remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:297–316. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HP, Vance RB, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. The prevalence and diagnostic utility of endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:988–996. e985. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, Huprich J, Kujath C, et al. Esophageal diameter is decreased in some patients with eosinophilic esophagitis and might increase with topical corticosteroid therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Runge TM, Eluri S, Cotton CC, et al. Outcomes of Esophageal Dilation in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Safety, Efficacy, and Persistence of the Fibrostenotic Phenotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:206–213. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasilopoulos S, Murphy P, Auerbach A, et al. The small-caliber esophagus: an unappreciated cause of dysphagia for solids in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:99–106. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.118645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assa’ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dellon ES, Aderoju A, Woosley JT, Sandler RS, Shaheen NJ. Variability in diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2300–2313. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–1206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:30–36. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181788282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030. quiz 1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapel RC, Miller JK, Torres C, Aksoy S, Lash R, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a prevalent disease in the United States that affects all age groups. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1316–1321. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackenzie SH, Go M, Chadwick B, et al. Eosinophilic oesophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia--a prospective analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1140–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasha SF, DiBaise JK, Kim HJ, et al. Patient characteristics, clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a case series and systematic review of the medical literature. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:311–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in clinical management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1238–1254. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoepfer AM, Straumann A, Panczak R, et al. Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1255–1266. e1221. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dellon ES, Rusin S, Gebhart JH, et al. Utility of a Noninvasive Serum Biomarker Panel for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:821–827. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellon ES, Rusin S, Gebhart JH, et al. A Clinical Prediction Tool Identifies Cases of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Without Endoscopic Biopsy: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1347–1354. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Markers of eosinophilic inflammation for diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis and proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:2015–2022. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Clinical and endoscopic characteristics do not reliably differentiate PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis in patients undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1854–1860. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Distribution and variability of esophageal eosinophilia in patients undergoing upper endoscopy. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:383–390. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, Rao MS, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dellon ES, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Inter- and intraobserver reliability and validation of a new method for determination of eosinophil counts in patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1940–1949. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Arnim U, Wex T, Rohl FW, et al. Identification of clinical and laboratory markers for predicting eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Digestion. 2011;84:323–327. doi: 10.1159/000331142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abonia JP, Wen T, Stucke EM, et al. High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slack MA, Ogbogu PU, Phillips G, Platts-Mills TA, Erwin EA. Serum vitamin D levels in a cohort of adult and pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentile N, Katzka D, Ravi K, et al. Oesophageal narrowing is common and frequently under-appreciated at endoscopy in patients with oesophageal eosinophilia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1333–40. doi: 10.1111/apt.12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menard-Katcher C, Swerdlow MP, Mehta P, et al. Contribution of Esophagram To The Evaluation of Complicated Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61:541–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]