Abstract

Objective

The aim was to assess diagnostic accuracy of 15 shoulder special tests for rotator cuff tears.

Design

From 02/2011 to 12/2012, 208 participants with shoulder pain were recruited in a cohort study.

Results

Among tests for supraspinatus tears, Jobe’s test had a sensitivity of 88% (95% CI=80% to 96%), specificity of 62% (95% CI=53% to 71%), and likelihood ratio of 2.30 (95% CI=1.79 to 2.95). The full can test had a sensitivity of 70% (95% CI=59% to 82%) and a specificity of 81% (95% CI=74% to 88%). Among tests for infraspinatus tears, external rotation lag signs at 0° had a specificity of 98% (95% CI=96% to 100%) and a likelihood ratio of 6.06 (95% CI=1.30 to 28.33), and the Hornblower’s sign had a specificity of 96% (95% CI=93% to 100%) and likelihood ratio of 4.81 (95% CI=1.60 to 14.49).

Conclusions

Jobe’s test and full can test had high sensitivity and specificity for supraspinatus tears and Hornblower’s sign performed well for infraspinatus tears. In general, special tests described for subscapularis tears have high specificity but low sensitivity. These data can be used in clinical practice to diagnose rotator cuff tears and may reduce the reliance on expensive imaging.

Keywords: Rotator cuff tear, special tests, sensitivity, physical examination

INTRODUCTION

Shoulder pain is a common musculoskeletal complaint1,2,3. Among patients with shoulder pain, rotator cuff tear is one of the most common cause for their symptoms4,5. Despite the wide prevalence of rotator cuff tears in patients with shoulder pain, their diagnosis based on clinical examination remains challenging and clinicians resort to expensive magnetic resonance imaging to make a diagnosis. Several physical examination maneuvers including “special tests” are described to assist in the diagnosis of a rotator cuff tear6,7. However, data on the sensitivity and specificity of special tests are sparse and conflicting, providing little guidance to the clinician in the diagnosis of this common musculoskeletal disorder. This issue is highlighted in several recent expert reviews8–10. Thus, there is need for studies assessing diagnostic accuracy of special tests for rotator cuff tears to guide the clinician during their physical examination. Data on special tests may assist the clinician in deciding the tests that they can rely on and make informed decisions about the certainty of their clinical diagnosis.

This study assessed the sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratio of 15 shoulder special tests that are described for the rotator cuff and biceps tendon. The study also presents an update of the systematic review performed by Hegedus et al.11,12 on the diagnostic accuracy of special tests for rotator cuff tears. The systematic review was performed to provide a synthesis of existing data on this topic and to compare to results of this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

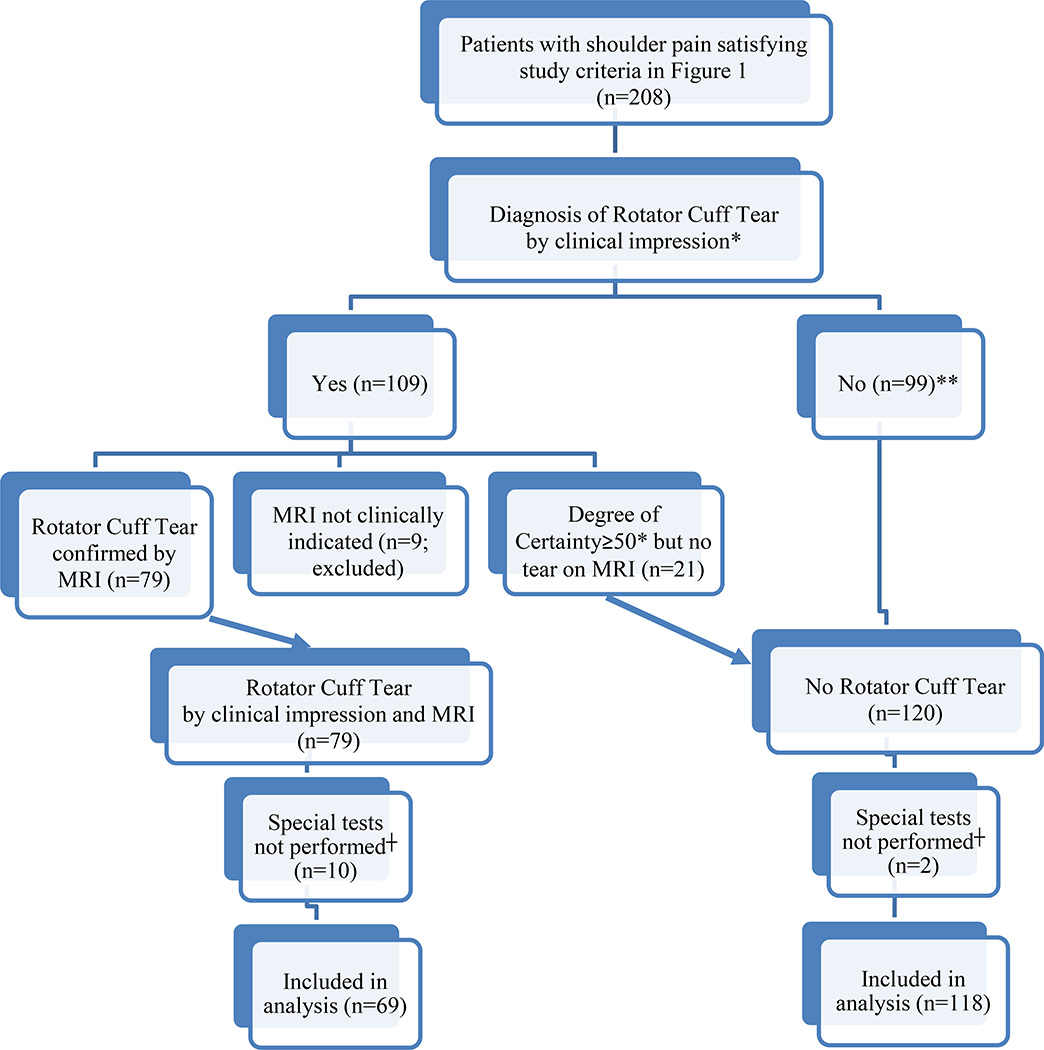

After approval from institutional review boards and written informed consent from each patient was obtained, patients presenting to sports medicine/shoulder clinics at two academic medical centers were recruited in an ongoing longitudinal cohort study termed ROW (Rotator Cuff Outcomes Workgroup). This prospective study was designed to include patients older than 45 years of age with shoulder pain for at least 4 weeks. The remaining inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Figure 1. Between 02/2011 and 12/2012, 208 participants with shoulder pain were recruited. Each patient underwent a standardized physical examination protocol including special tests (described below). Twelve patients had missing data on special tests due to time constraints in clinic to complete the research protocol and 9 patients had clinical assessment notable for a rotator cuff tear but did not have a MRI (Figure 2). These patients were excluded from the analysis. This study complies with the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) guidelines (Appendix A).

Figure 1. Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria.

Figure 2. Schematic of Patient Population.

*Determined by a clinical degree of certainty that patient’s symptoms were attributable to a rotator cuff tear of ≥50 on a 0–100 scale

**If patients were clinically determined to not have a rotator cuff tear (degree of certainty<50), they were given a diagnosis of No Rotator Cuff Tear irrespective of imaging findings

┼Due to time constraints in clinic

Physical Exam Protocol

Patients underwent a standardized physical examination including special tests by a physician (shoulder/sports medicine fellow or orthopedic resident) or an orthopedic physician assistant. Special tests performed included lift off test, passive lift off test, belly-press test, belly-off sign, bear hug, external rotation lag sign at 0°, external rotation lag sign at 90°, Hornblower’s sign, full can test, drop arm test, Jobe’s test, Neer’s sign, Hawkin’s sign, bicipital groove tenderness, and Speed’s test. The tests were not always performed in the same order. The clinicians were not blinded to the patient’s clinical history. Prior to June 2012, each of the clinicians performing these tests was trained by the attending physicians (LDH or JPW) by demonstration of each one of the test maneuvers as part of the research protocol. Starting in June 2012, this training was further standardized by requiring the clinicians performing the tests to view a video that demonstrated all of the special tests. This video was specifically prepared for this study and one of the investigators with over 15 years of experience in clinical sports/shoulder medicine (LDH) demonstrated all of the maneuvers based on their original descriptions (except for the drop arm test where the description by Woodward et al.13 was used since no original article could be traced to this test). Prior to production of this video, a handout was prepared that included descriptions of each one of the special tests under the sub-headings “Reference” (citation of the original article that described the test), “Study Procedure” (description of the test maneuver as per the original article), “Interpretation” (when to report the test as positive or negative as per the original article), and “Figure” (when available from the original article or another reference). This handout was reviewed by two shoulder experts with over 15 years of experience (LDH and JPW) for accuracy prior to commencement of the study. A reference sheet with abbreviated descriptions of the special tests was also available to the clinicians performing these tests. The standardized physical examination protocol and description of special tests has been previously described6 and good inter-rater and intra-rater reliability has been reported for performance of many of these tests14–17. Inter-rater or intra-rater reliability among clinicians in this study was not performed due to existing data on this issue.

Diagnostic Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on a General Electric (Waukesha, WI, USA) using a dedicated shoulder coil (Invivo, Gainesville, FL, USA). Shoulder MRI images were read by two shoulder experts by consensus (NBJ, a recent fellowship graduate, and LDH, a shoulder surgeon with over 15 years of experience) using a standardized MRI reading form at least 2 months after the clinical encounter. The MRI reviewers were blinded to clinical findings when assessing the images. Substantial intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of MRI assessments when compared with a musculoskeletal radiologist with point estimates for kappa ranging from 0.75 to 0.90 for tear presence, tear size, and tear thickness has been shown18. Some of the features assessed during blinded MRI review included the presence of a full-thickness tear and partial-thickness tear. Other characteristics reviewed included the presence of biceps tendon pathology (tenosynovitis, tendinosis/tendonitis, and subluxation or dislocation from the bicipital groove), labral tear, and acromioclavicular joint arthrosis. X-rays were also reviewed in a blinded manner for the presence of glenohumeral joint and acromioclavicular joint arthrosis.

Diagnosis of Rotator Cuff Tear (Reference Standard)

Rotator cuff tears are documented on imaging in asymptomatic individuals19–22. Therefore, a case definition based solely on structure is not clinically relevant. In this study, a fellowship trained shoulder or sports medicine attending physician performed an independent clinical assessment (history and physical examination). Based on their clinical assessment the attending physician rated the degree of certainty that the patient’s symptoms were attributable to a rotator cuff tear on a scale ranging from 0 (certainly not a tear) to 100 (certainly a tear). If the degree of certainty was marked as ≥50 and the blinded MRI review (as described above) determined that there was structural evidence for a rotator cuff tear, the patient was considered to have a diagnosis of rotator cuff tear. Thus, this methodology used both an expert clinician’s impression and imaging for diagnosing rotator cuff tears9. The diagnosis of biceps tendon pathology was also based on the physician indicating that the patient had clinical signs and symptoms corresponding to biceps disease (a “yes/no” question) and the presence of biceps tendon pathology on blinded MRI review.

Statistical Analysis

Test performance characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Confidence intervals were calculated using a normal approximation for sensitivity and specificity and methodology described by Koopman23 for likelihood ratios. Due to the multiple rotator cuff tests that were assessed in this study, a single flow diagram of test results as suggested in STARD guidelines was not possible. Instead, these results are presented in the table. As recommended in recent literature24, the number of patients in whom special tests had valid inconclusive results are also presented. Inconclusive results were obtained because these patients were in too much pain at baseline to interpret the test result as positive or negative. “Test yield” calculated as the percentage of test results included in the calculation of diagnostic accuracy parameters after exclusion of patients with inconclusive results25 is also presented. The test yield calculation does not account for patients who had missing data. The higher the test yield, the fewer the patients that were excluded due to inconclusive testing results when calculating the summary statistic.

Systematic Review of Literature

The literature review in this study is an update of the comprehensive review and meta-analysis published by Hegedus et al.11,12 The authors reviewed literature on special tests for the shoulder until February 2012 and utilized the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool to assess study quality. The term rotator cuff disorder/syndrome can be used to describe rotator cuff tear or less specific shoulder disorders such as subacromial/subdeltoid bursitis, impingement syndrome, or rotator cuff tendinosis/tendonitis. Since this study focuses on rotator cuff tears that can be more discretely diagnosed using imaging and physical examination, studies from the reviews by Hegedus et al. which specifically assessed rotator cuff tear were extracted. In addition we also performed a literature search using the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL databases for articles published after February 2012 and until March 2014 on sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of special tests for rotator cuff tear. This search yielded 3 additional published studies26,27,28 on this topic since the time frame covered by Hegedus articles. A study by Faruqui29 was excluded because it reported on sensitivity of belly press, lift-off, and bear hug tests combined (and not as individual tests). In addition to the diagnostic accuracy characteristics reported by the authors in their respective manuscripts, when possible, additional diagnostic accuracy parameters (sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, and predictive values) not reported in the original manuscript were calculated. Likelihood ratios assuming the prevalence of rotator cuff tear in patients with shoulder pain to be 15% and 50%, to represent primary care settings and specialty settings, respectively, were calculated.

RESULTS

The mean age of participants in this study with a rotator cuff tear was 62.8±9.6 years as compared to 60±9.1 years for those without a rotator cuff tear (Table 1). No major adverse events were recorded during performance of special tests or MRI.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population

| Rotator Cuff Tear | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| (n=69) | (n=118) | |

| n (%) or | n (%) or | |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation |

Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|

| Age | 62.8 ± 9.6 | 60.0 ± 9.1 |

| Female | 32 (46.4 %) | 61 (51.7 %) |

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 61 (88.4 %) | 106 (91.4 %) |

| Affected Shoulder┼ | ||

| Right | 49 (71.0 %) | 63 (53.8 %) |

| Left | 20 (29.0 %) | 49 (41.9 %) |

| Both | 0 | 5 (4.3%) |

| Affected Shoulder | ||

| Dominant | 46 (66.7%) | 66 (55.9%) |

| Non-dominant | 23 (33.3%) | 52 (44.1%) |

| Symptom duration (months) | 26.9 ± 43.0 | 30.2 ± 55.7 |

| Visual Analog Pain Score┼ | 43.4 ± 27.0 | 56.6 ± 23.5 |

| Shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI)┼ |

50.3 ± 24.7 | 40.8 ± 23.3 |

| Select diagnosis* | ||

| Rotator cuff tear | 69 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Biceps pathology | 10 (14.5 %) | 6 (5.1 %) |

| Acromioclavicular joint arthritis | 0 | 2 (1.7 %) |

| Glenohumeral osteoarthritis | 7 (10.1 %) | 33 (28.7 %) |

| Labral tear | 0 | 1 (0.9 %) |

| Adhesive capsulitis | 1 (1.4 %) | 22 (18.6 %) |

| Other shoulder disorders | - | 54 (45.8%) |

| Tendon torn║ | N/A | |

| Subscapularis | 14 (20%) | |

| Infraspinatus | 32 (46%) | |

| Supraspinatus | 64 (93%) | |

| Teres minor | 0 | |

| Size of tear** | N/A | |

| Partial-thickness | 19 (28%) | |

| <2 cm full-thickness | 15 (22%) | |

| ≥2 cm full-thickness | 34 (50%) | |

Diagnosis is based on clinical impression and imaging for all diagnoses except for adhesive capsulitis where the diagnosis was based on only clinical impression. Diagnoses categories may not be mutually exclusive

larger of longitudinal or transverse size dimension presented

p<0.05 for difference between those with and without rotator cuff tear

Total is greater than 100% because patients may have multiple tendons involved

The Jobe’s test had a sensitivity of 88% (95% CI=80%–96%), specificity of 62% (95% CI=53%–71%), and likelihood ratio of 2.30 (95% CI=1.79–2.95) (Tables 2 and 3). The drop arm test had a specificity of 96% (95% CI=93%–100%), sensitivity of 24% (95% CI=14%–34%), and likelihood ratio of 6.45 (95% CI=2.25–18.47). Diagnostic accuracy values for other tests are provided in Tables 2 and 3. When stratified by tear size, the drop arm test had a sensitivity of 21% (95% CI=7%–35%), a specificity of 96% (95% CI=93%–100%), and a likelihood ratio of 5.73 (95% CI=1.79–18.36) (Table 3a; Appendix B) for diagnosing larger supraspinatus tears of ≥2 cms. The Jobe’s test, full can test, Neer’s sign, and Hawkin’s also had similar diagnostic accuracy in detecting larger supraspinatus tears of ≥2 cms as compared with the overall population of patients with supraspinatus tears.

Table 2.

Results of Special Tests for Rotator Cuff Tear Diagnosis

| Rotator Cuff Tear |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subscapularis | Tear | No Tear | |

| Lift off test | Positive | 13 | 6 |

| Negative | 45 | 96 | |

| Inconclusive | 2 | 3 | |

| Passive lift off | Positive | 11 | 5 |

| Negative | 48 | 96 | |

| Inconclusive | 1 | 2 | |

| Belly-press test | Positive | 18 | 14 |

| Negative | 46 | 97 | |

| Inconclusive | 2 | 1 | |

| Belly-off sign | Positive | 11 | 4 |

| Negative | 51 | 104 | |

| Inconclusive | 1 | 1 | |

| Bear hug | Positive | 20 | 21 |

| Negative | 43 | 91 | |

| Inconclusive | 1 | 0 | |

| Infraspinatus | Tear | No Tear | |

| External rotation | Positive | 7 | 2 |

| lag sign at 0° | Negative | 60 | 114 |

| Inconclusive | 0 | 0 | |

| External rotation | Positive | 5 | 0 |

| lag sign at 90° | Negative | 58 | 112 |

| Inconclusive | 0 | 1 | |

| Hornblower’s sign | Positive | 11 | 4 |

| Negative | 53 | 108 | |

| Inconclusive | 1 | 1 | |

| Rotator Cuff Tear | |||

| Supraspinatus | Tear | No Tear | |

| Full can test | Positive | 45 | 21 |

| Negative | 19 | 91 | |

| Inconclusive | 1 | 0 | |

| Drop arm test | Positive | 16 | 4 |

| Negative | 51 | 104 | |

| Inconclusive | 0 | 0 | |

| Jobe’s test | Positive | 58 | 44 |

| Negative | 8 | 71 | |

| Inconclusive | 1 | 0 | |

| Neer’s sign | Positive | 40 | 47 |

| Negative | 27 | 65 | |

| Inconclusive | 1 | 0 | |

| Hawkin’s sign | Positive | 43 | 58 |

| Negative | 24 | 53 | |

| Inconclusive | 1 | 0 | |

| Biceps Pathology | |||

| Present | Absent | ||

| Bicipital groove | Positive | 11 | 72 |

| tenderness | Negative | 5 | 97 |

| Inconclusive | 0 | 0 | |

| Speed’s test | Positive | 12 | 87 |

| Negative | 4 | 70 | |

| Inconclusive | 0 | 1 | |

Number of patients missing values: lift off test=22; passive lift off=24; belly-press test=9; belly-off sign=15; bear hug=11; external rotation lag sign at 0°=4; external rotation lag sign at 90°=11; hornblower’s sign=9; full can test=10; drop arm test=12; Jobe’s test=5; Neer’s sign=7; Hawkin’s sign=8; bicipital groove tenderness=1, and; Speed’s test=12

Table 3.

Diagnostic Accuracy of Special Tests in Rotator Cuff Tear Diagnosis

| Number of Patients with Tear |

Sensitivity (%) (95% Confidence Intervals) |

Specificity (%) (95% Confidence Intervals) |

Likelihood Ratio (+) (95% Confidence Intervals) |

Test Yield* (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUBSCAPULARIS | |||||

| Lift off test | 60 | 22 (12–33) | 94 (90–99) | 3.81 (1.53–9.49) | 97.0 |

| Passive lift off | 60 | 19 (9–29) | 95 (91–99) | 3.77 (1.38–10.31) | 98.2 |

| Belly-press test | 66 | 28 (17–39) | 87 (81–94) | 2.23 (1.19–4.17) | 98.3 |

| Belly-off sign | 63 | 18 (8–27) | 96 (93–100) | 4.79 (1.59–14.41) | 98.8 |

| Bear hug | 64 | 32 (20–43) | 81 (74–88) | 1.69 (1.0–2.87) | 99.4 |

| INFRASPINATUS | |||||

|

External rotation lag sign at 0° |

67 | 10 (3–18) | 98 (96–100) | 6.06 (1.30–28.33) | 100 |

|

External rotation lag sign at 90 ° |

63 | 8 (1–15) | 100 (100–100) | - | 99.4 |

| Hornblower’s sign | 65 | 17 (8–26) | 96 (93–100) | 4.81 (1.60–14.49) | 98.9 |

| SUPRASPINATUS | |||||

| Jobe's test | 67 | 88 (80–96) | 62 (53–71) | 2.30 (1.79–2.95) | 99.5 |

| Full can test | 65 | 70 (59–82) | 81 (74–88) | 3.75 (2.47–5.69) | 99.4 |

| Drop arm test | 67 | 24 (14–34) | 96 (93–100) | 6.45 (2.25–18.47) | 100 |

| Neer's sign | 68 | 60 (48–71) | 58 (49–67) | 1.42 (1.06–1.91) | 99.4 |

| Hawkin's sign | 68 | 64 (53–76) | 48 (38–57) | 1.23 (0.95–1.58) | 99.4 |

| BICEPS PATHOLOGY | |||||

| Speed's test | 16 | 75 (54–96) | 45 (37–52) | 1.35 (0.99–1.86) | 99.4 |

|

Bicipital groove tenderness |

16 | 69 (46–91) | 57 (50–65) | 1.61 (1.11–2.35) | 100 |

The external rotation lag signs at 0° had a specificity of 98% (95% CI=96%–100%) with a likelihood ratio of 6.06 (95% CI=1.30–28.33) for detecting infraspinatus tears. Similar values were obtained for the external rotation lag sign at 0° for detecting larger infraspinatus tears of ≥2 cms (Sensitivity: 21%; 95% CI=6%–37%; Specificity: 98%; 95% CI=96%–100%; Likelihood Ratio: 12.43; 95% CI=2.65–58.34) (Table 3a; Appendix B).

The systematic review of literature showed a wide variation in sensitivity and specificity of special tests (Table 4 and Appendix B, Table 4a). The sensitivity of Jobe’s test to detect supraspinatus tears ranged from 19% to 99% and specificity ranged from 39% to 100% when increased pain or weakness was a considered as a positive test. The lift-off test had a sensitivity ranging from 6%–79% and specificity ranging from 23%–100% for detection of subscapularis tears.

Table 4.

Summary of Literature on Diagnostic Value of Select Special Tests for Rotator Cuff Tear

| Special Test References | # of Subjects Range |

Sensitivity Range |

Specificity Range |

Likelihood Ratio (+) Range |

Likelihood Ratio (−) Range |

Negative Predictive Value Range |

Positive Predictive Value Range (Based on Varying Rotator Cuff Tear Prevalence) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence as in Publication |

Prevalence of 50% |

Prevalence of 15% |

|||||||

| Lift-off test 26–28,32–34 | 49–312 | 6–79 | 23–100 | 0.1–1.9 | 0.4–4.1 | 61–88 | 20–100 | 7–100 | 4–100 |

| Belly press test 26–28 | 49–312 | 43–76 | 93–99 | 6–28 | 0.6–0.7 | 65–91 | 50–97 | 86–96 | 15–20 |

| Belly off sign 28 | 49 | 14 | 95 | 3 | 0.9 | 86 | 33 | 74 | 15 |

| Bear hug test 26,27 | 165–208 | 19–82 | 99 | 19.0 | 0.8 | 64 | 93 | 95 | 18 |

|

External rotation Lag sign 28,30,36,47,48 |

46–1913 | 35–100 | 89–98 | 4.0–28.0 | 0–0.7 | 0.7–99 | 0.7–87 | 76–97 | 14–19 |

|

Jobe’s test/ Empty can* 28,32,49 |

49–200 | 78–94 | 40–55 | 1.3–2.0 | 0.1–0.6 | 89–94 | 46–53 | 57–66 | 0.1–9 |

|

Jobe’s test/Empty can**32,49 |

160–200 | 76–87 | 43–71 | 1.5–2.6 | 0.3 | 86 | 56 | 60–72 | 7–11 |

|

Jobe’s test/Empty can*** 30,33–35,49 |

34–200 | 19–99 | 39–100 | 0.6–1.7 | 0–1.3 | 54–98 | 46–100 | 1–63 | 1–8 |

|

Jobe’s test/Empty can¶ 49 |

200 | 71 | 74 | 2.7 | 0.4 | 84 | 57 | 73 | 12 |

| Full can test* 32,49 | 160–200 | 71–80 | 50–68 | 1.6–2.2 | 0.4 | 91 | 52 | 62–69 | 8–11 |

| Full can** 32,49 | 160–200 | 77–83 | 53–68 | 1.8–2.4 | 0.3 | 86 | 54 | 64–71 | 9–11 |

| Full can*** 49 | 200 | 90 | 54 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 92 | 49 | 66 | 9 |

| Full can¶ 49 | 200 | 59 | 82 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 80 | 62 | 77 | 13 |

| Drop arm test 28,30 | 49–104 | 41–50 | 83 | 2.4–2.9 | 0.6–0.7 | 53–89 | 36–75 | 71–75 | 13 |

| Neer’s sign 30 | 104 | 60 | 35 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 38 | 52 | 48 | 6 |

|

Hawkin’s sign or Hawkins- Kennedy 30 |

104 | 77 | 26 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 50 | 58 | 51 | 4 |

|

Speed’s test 36,44,45,50–52 |

60 -1913 | 49–71 | 60–85 | 1.5–4.7 | 0.3–0.8 | 30–96 | 8–89 | 60–83 | 10–14 |

|

Obrien’s sign or active compression test 36,50 |

325–1913 | 38–68 | 46–61 | 0.96–1.2 | 0.7–1.0 | 67 | 31 | 49–56 | 8–10 |

Increased pain was a positive result

Weakness was a positive result

Increased pain or weakness was a positive test

Increased pain and weakness was a positive test

DISCUSSION

Special tests are extensively described in the literature6–8 but data on diagnostic accuracy of special tests is sparse and inconclusive, thereby leading to heavy reliance on expensive shoulder imaging to aid in the diagnosis8–10. Prior studies have provided data on individual or only few of the special tests described for the rotator cuff26,27,30–35. This issue was addressed in this study by assessing 15 tests commonly used for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tear and biceps pathology. Prior studies also had limitations such as recruitment from single sites/providers or data obtained by retrospective chart review27,28,30,32–36 This study addressed these limitations by recruiting from multiple sites and providers, and recruiting patients prospectively. Prior studies have also used either imaging or surgical findings as reference standard for their case definition of a rotator cuff tear26–28,30–36. Although MRI/MRA have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tear37–41, it is well-documented that rotator cuff tears are present even in asymptomatic individuals19–22. Thus, imaging findings alone are not sufficient to constitute the diagnosis of a clinically symptomatic rotator cuff tear and an expert clinician’s impression that the symptoms of a patient with shoulder pain are attributable to a rotator cuff tear forms an essential component in the diagnosis of this clinical syndrome9. This issue was addressed in this study by using a strict imaging and clinical criteria for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tear.

Prior studies have reported a sensitivity of 19%–94%, specificity of 39%–100%, and likelihood ratio of 0.6–2.7 for Jobe’s test. Data from this study shows high sensitivity and specificity for the Jobe’s test. The variation in results of prior studies is possibly explained by difference in patient populations, heterogeneity in the gold standard used for diagnosis of cuff tear, and recruitment of only patients undergoing surgery. As compared with the Jobe’s test, the full can test had a higher likelihood ratio which represents a greater likelihood that there would be a positive test in a patient with rotator cuff tear as opposed to one without a tear42. Likelihood ratios are described in the literature as one of the most useful measures of diagnostic accuracy since they can be used to calculate post-test probability based on prevalence of disease using a normogram43. However, likelihood ratios in this study should be interpreted with caution in tests such as the drop arm that have high specificity and low sensitivity (resulting in a high likelihood ratio). Data in this study shows that if the drop arm test is positive one can almost be certain that the patient has a supraspinatus tear but a negative test does not provide conclusive information to the examiner. The drop arm test also cannot be used as a screening test due to its low sensitivity. This paradigm also applies to the lag signs for infraspinatus tears. Data from this study shows near perfect specificity and a low sensitivity for lag signs. Prior studies are in agreement with these findings of high specificity (89%–98%) but have reported a wide range of sensitivity (35%–100%) due to variability in the patient populations and reference standards used in these studies34,36,41,44,45. Again, the variation in results in prior studies is likely due to patient population used and relatively smaller sample sizes. For subscapularis tears, the lift-off test has the most available data from prior studies with sensitivity ranging from 6% to 79% and specificity ranging from 23% to 97% 26–28,32–34. This study found a high specificity and low sensitivity for the lift-off test. Tests with a high specificity and low sensitivity indicate that the patient is very likely to have a rotator cuff tear if the test is positive whereas due to the low sensitivity of such tests, their utility is limited when the test is negative.

The inclusion of patients from specialty clinics in this study may have increased the disease (rotator cuff tear) prevalence limiting the generalizability of results to primary care settings. This study design was deliberately chosen a priori to allow for a strong basis (the clinical impression of a sub-specialty trained shoulder expert) for the clinical diagnosis of rotator cuff tear. Other limitations of this study include the relatively fewer patients with subscapularis tears in the cohort and possible variability in performance of special tests among different examiners. However, good inter-rater and intra-rater reliability has been reported for performance of most special tests14–17 and extensive standardization of special test performance was done in this study. The fewer patients with subscapularis tears in the cohort also represents the usual patient population with cuff tears where supraspinatus is the most commonly torn tendon46.

In summary this study presents data on 15 commonly performed special tests for the rotator cuff and biceps tendon. This study provides evidence for high sensitivity and specificity of the Jobe’s tear and full can test for supraspinatus tears. The lag signs and the Hornblower’s sign for infraspinatus tears had high specificity but low sensitivity, thus useful if the test is positive which indicates a high likelihood of rotator cuff tear. In general, special tests described for subscapularis tears have high specificity but low sensitivity. The belly-press test and bear hug tests had the highest sensitivities of all tests assessed for subscapularis tears. This data can be used in clinical practice to diagnose rotator cuff tears and proximal biceps tendon pathology and may reduce the reliance on expensive imaging for these purposes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Jain is supported by funding from National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) 1K23AR059199, Foundation for PM&R, and Biomedical Research Institute at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Katz is in part supported by NIAMS P60 AR 047782.

The funding agencies had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

The project described was supported by the National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1RR024975-01, and is now the National Center for Advancing Transational Sciences, Grant UL1TR000445-06. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

An abstract of this study was presented at the Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R) annual assembly in San Diego, CA in November 2014.

References

- 1.CDC/NCHS. [Accessed Jan 25, 2013];National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Summary Tables. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/web_tables.htm#2010.

- 2.Stevenson JH, Trojian T. Evaluation of shoulder pain. Journal of family practice. 2002;51(7):605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen AL, Shapiro JA, Ahn AK, Zuckerman JD, Cuomo F. Rotator cuff repair in patients with type I diabetes mellitus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):416–421. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(03)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chard MD, Hazleman R, Hazleman BL, King RH, Reiss BB. Shoulder disorders in the elderly: a community survey. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1991;34(6):766–769. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vecchio P, Kavanagh R, Hazleman BL, King RH. Shoulder pain in a community-based rheumatology clinic. British journal of rheumatology. 1995;34(5):440–442. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain NB, Wilcox RB, 3rd, Katz JN, Higgins LD. Clinical examination of the rotator cuff. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2013;5(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tennent TD, Beach WR, Meyers JF. A review of the special tests associated with shoulder examination. Part I: the rotator cuff tests. The American journal of sports medicine. 2003;31(1):154–160. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310011101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermans J, Luime JJ, Meuffels DE, Reijman M, Simel DL, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Does this patient with shoulder pain have rotator cuff disease?: The Rational Clinical Examination systematic review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310(8):837–847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain NB, Yamaguchi K. History and physical examination provide little guidance on diagnosis of rotator cuff tears. Evidence-based medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1136/eb-2013-101593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanchard NC, Lenza M, Handoll HH, Takwoingi Y. Physical tests for shoulder impingements and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;4:CD007427. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007427.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S, et al. Physical examination tests of the shoulder: a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. British journal of sports medicine. 2008;42(2):80–92. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.038406. discussion 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegedus EJ, Goode AP, Cook CE, et al. Which physical examination tests provide clinicians with the most value when examining the shoulder? Update of a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. British journal of sports medicine. 2012;46(14):964–978. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodward TW, Best TM. The painful shoulder: part I. Clinical evaluation. American family physician. 2000;61(10):3079–3088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadogan A, Laslett M, Hing W, McNair P, Williams M. Interexaminer reliability of orthopaedic special tests used in the assessment of shoulder pain. Manual therapy. 2011;16(2):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dromerick AW, Kumar A, Volshteyn O, Edwards DF. Hemiplegic shoulder pain syndrome: interrater reliability of physical diagnosis signs. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2006;87(2):294–295. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansson K, Ivarson S. Intra- and interexaminer reliability of four manual shoulder maneuvers used to identify subacromial pain. Manual therapy. 2009;14(2):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michener LA, Walsworth MK, Doukas WC, Murphy KP. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of 5 physical examination tests and combination of tests for subacromial impingement. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2009;90(11):1898–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain NB, Collins J, Newman JS, Katz JN, Losina E, Higgins LD. Reliability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Assessment of Rotator Cuff: The ROW Study. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.08.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milgrom C, Schaffler M, Gilbert S, van Holsbeeck M. Rotator-cuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand dominance and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(2):296–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sher JS, Uribe JW, Posada A, Murphy BJ, Zlatkin MB. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(1):10–15. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Galatz LM, Teefey SA. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1699–1704. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi K, Tetro AM, Blam O, Evanoff BA, Teefey SA, Middleton WD. Natural history of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a longitudinal analysis of asymptomatic tears detected sonographically. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):199–203. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.113086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koopman PAR. Confidence intervals for the ratio of two binomial proportions. Biometrics. 1984;40(2):513–517. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinkins B, Thompson M, Mallett S, Perera R. Diagnostic accuracy studies: how to report and analyse inconclusive test results. Bmj. 2013;346:f2778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simel DL, Feussner JR, DeLong ER, Matchar DB. Intermediate, indeterminate, and uninterpretable diagnostic test results. Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 1987;7(2):107–114. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8700700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barth J, Audebert S, Toussaint B, et al. Diagnosis of subscapularis tendon tears: are available diagnostic tests pertinent for a positive diagnosis? Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2012;98(8 Suppl):S178–S185. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon JP, Chung SW, Kim SH, Oh JH. Diagnostic value of four clinical tests for the evaluation of subscapularis integrity. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1186–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuen CK, Mok KL, Kan PG. The validity of 9 physical tests for full-thickness rotator cuff tears after primary anterior shoulder dislocation in ED patients. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2012;30(8):1522–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faruqui S, Wijdicks C, Foad A. Sensitivity of physical examination versus arthroscopy in diagnosing subscapularis tendon injury. Orthopedics. 2014;37(1):e29–e33. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20131219-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bak K, Sorensen AK, Jorgensen U, et al. The value of clinical tests in acute full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus tendon: does a subacromial lidocaine injection help in the clinical diagnosis? A prospective study. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2010;26(6):734–742. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barth JR, Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. The bear-hug test: a new and sensitive test for diagnosing a subscapularis tear. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2006;22(10):1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itoi E, Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Seki N, Abe H. Are pain location and physical examinations useful in locating a tear site of the rotator cuff? The American journal of sports medicine. 2006;34(2):256–264. doi: 10.1177/0363546505280430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim HA, Kim SH, Seo YI. Ultrasonographic findings of painful shoulders and correlation between physical examination and ultrasonographic rotator cuff tear. Modern rheumatology / the Japan Rheumatism Association. 2007;17(3):213–219. doi: 10.1007/s10165-007-0577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim HAKSH, Seo Y-I. Ultrasonographic findings of the shoulder in pateitns with rheumatoid arthritis and comparison with physical examination. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:660–666. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.4.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naredo EAP, De Miguel E, Uson J, Mayordomo L, Gijon-Banos J, Martin-Mola E. Painful shoulder: comparison of physical examination and ultrasonographic findings. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:132–136. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia X, Petersen SA, Khosravi AH, Almareddi V, Pannirselvam V, McFarland EG. Examination of the shoulder: the past, the present, and the future. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(Suppl 6):10–18. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanchard TK, Bearcroft PW, Constant CR, Griffin DR, Dixon AK. Diagnostic and therapeutic impact of MRI and arthrography in the investigation of full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Eur Radiol. 1999;9(4):638–642. doi: 10.1007/s003300050724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dinnes J, Loveman E, McIntyre L, Waugh N. The effectiveness of diagnostic tests for the assessment of shoulder pain due to soft tissue disorders: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(29):iii, 1–166. doi: 10.3310/hta7290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Habibian A, Stauffer A, Resnick D, et al. Comparison of conventional and computed arthrotomography with MR imaging in the evaluation of the shoulder. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13(6):968–975. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198911000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamakawa S, Hashizume H, Ichikawa N, Itadera E, Inoue H. Comparative studies of MRI and operative findings in rotator cuff tear. Acta Med Okayama. 2001;55(5):261–268. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zlatkin MB, Iannotti JP, Roberts MC, et al. Rotator cuff tears: diagnostic performance of MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;172(1):223–229. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.1.2740508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests. Bmj. 1997;315(7107):540–543. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7107.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fagan TJ. Letter: Nomogram for Bayes theorem. The New England journal of medicine. 1975;293(5):257. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197507312930513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen HS, Lin SH, Hsu YH, Chen SC, Kang JH. A comparison of physical examinations with musculoskeletal ultrasound in the diagnosis of biceps long head tendinitis. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2011;37(9):1392–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.05.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gill HS, El Rassi G, Bahk MS, Castillo RC, McFarland EG. Physical examination for partial tears of the biceps tendon. The American journal of sports medicine. 2007;35(8):1334–1340. doi: 10.1177/0363546507300058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hijioka A, Suzuki K, Nakamura T, Hojo T. Degenerative change and rotator cuff tears. An anatomical study in 160 shoulders of 80 cadavers. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 1993;112(2):61–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00420255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castoldi F, Blonna D, Hertel R. External rotation lag sign revisited: accuracy for diagnosis of full thickness supraspinatus tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller CA, Forrester GA, Lewis JS. The validity of the lag signs in diagnosing full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff: a preliminary investigation. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2008;89(6):1162–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim EJHJ, Lee KW, Song JS. Interpreting Positive Signs of the Supraspinatus Test in Screening for Torn Rotator Cuff. Acta Med Okayama. 2006;60(4):223–228. doi: 10.18926/AMO/30715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ben Kibler W, Sciascia AD, Hester P, Dome D, Jacobs C. Clinical utility of traditional and new tests in the diagnosis of biceps tendon injuries and superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions in the shoulder. The American journal of sports medicine. 2009;37(9):1840–1847. doi: 10.1177/0363546509332505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goyal P, Hemal U, Kumar R. High resolution sonographic evaluation of painful shoulder. Internet J Radiol. 2010;12:1. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salaffi F, Ciapetti A, Carotti M, Gasparini S, Filippucci E, Grassi W. Clinical value of single versus composite provocative clinical tests in the assessment of painful shoulder. Journal of clinical rheumatology : practical reports on rheumatic & musculoskeletal diseases. 2010;16(3):105–108. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181cf8392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.