Abstract

It has been almost 30 years since RNA interference (RNAi) was shown to silence genes via double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) in Caenorhabditis elegans (Fire et al. 1998). 20–30-nucleotide (nt) small non-coding RNAs are a key element of the RNAi machinery. Recently, phased small interfering RNAs (phasiRNAs), small RNAs that are generated from a long RNA precursor at intervals of 21 to 26-nt, have been identified in plants and animals. In Drosophila, phasiRNAs are generated by the endonuclease, Zucchini (Zuc), in germlines. These phasiRNAs, known as one of PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), mainly repress transposable elements. Similarly, reproduction-specific phasiRNAs have been identified in the family Poaceae, although DICER LIKE (DCL) protein-dependent phasiRNA biogenesis in rice is distinct from piRNA biogenesis in animals. In plants, phasiRNA biogenesis is initiated when 22-nt microRNAs (miRNAs) cleave single-stranded target RNAs. Subsequently, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDR) forms dsRNAs from the cleaved RNAs, and dsRNAs are further processed by DCLs into 21 to 24-nt phasiRNAs. Finally, the phasiRNAs are loaded to ARGONAUTE (AGO) proteins to induce RNA-silencing. There are diverse types of phasiRNA precursors and the miRNAs that trigger the biogenesis. Their expression patterns also differ among plant species, suggesting that species-specific combinations of these triggers dictate the spatio-temporal pattern of phasiRNA biogenesis during development, or in response to environmental stimuli.

Keywords: phasiRNAs, tasiRNAs, 22-nt miRNAs, DCL-processing, ARGONAUTE, Reproduction

Introduction

In the early 1990s, RNA silencing was reported as co-suppression and quelling in plants and fungi. Transgenes result in the suppression of endogenous transcripts with homologous transgene sequences (Napoli et al. 1990; Romano and Macino 1992). In Caenorhabditis elegans, double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) induce RNA silencing, called RNA interference (RNAi) (Fire et al. 1998). Small RNAs are key players in the RNAi machinery, and play pivotal roles during various developmental stages and in pathogenesis. In the plant RNAi pathway, 21–24-nucleotide (nt) small RNAs are produced via processing of dsRNAs by DICER LIKE (DCL) proteins encoding RNaseIII. Processed small RNAs are loaded onto Argonaute proteins (AGOs) and small RNA-AGO complexes trigger RNA-silencing through RNA cleavage or DNA methylation in a small RNA sequence-dependent manner (Castel and Martienssen 2013; Czech and Hannon 2011).

RNA silencing is classified into two types: transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) and post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS). In Arabidopsis thaliana, 24-nt repeat-associated siRNAs (rasiRNAs) bound to AGO4 cause RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) and TGS. TGS, mediated by rasiRNAs via DNA methylation, suppresses many transposable elements (TEs) and repeat regions to prevent their transposition and transmission to the next generation (Matzke et al. 2009). In contrast, PTGS silences genes via target-RNA cleavage and/or translational repression (Iwakawa and Tomari 2015). In PTGS induced by exogenous factors, such as transgenes or viral infections, dsRNAs formed in template exogenous RNAs by RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDR) and DCL-dependent processing result in production of 21-nt, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for defense against viral and exogenous transgenes (Hamilton and Baulcombe 1999). PTGS is also triggered by 21- or 22-nt micro RNAs (miRNAs), derived from hairpin structures, or 21-nt trans-acting siRNAs (tasiRNAs), which are one type of phased small interfering RNAs (phasiRNAs) in plants.

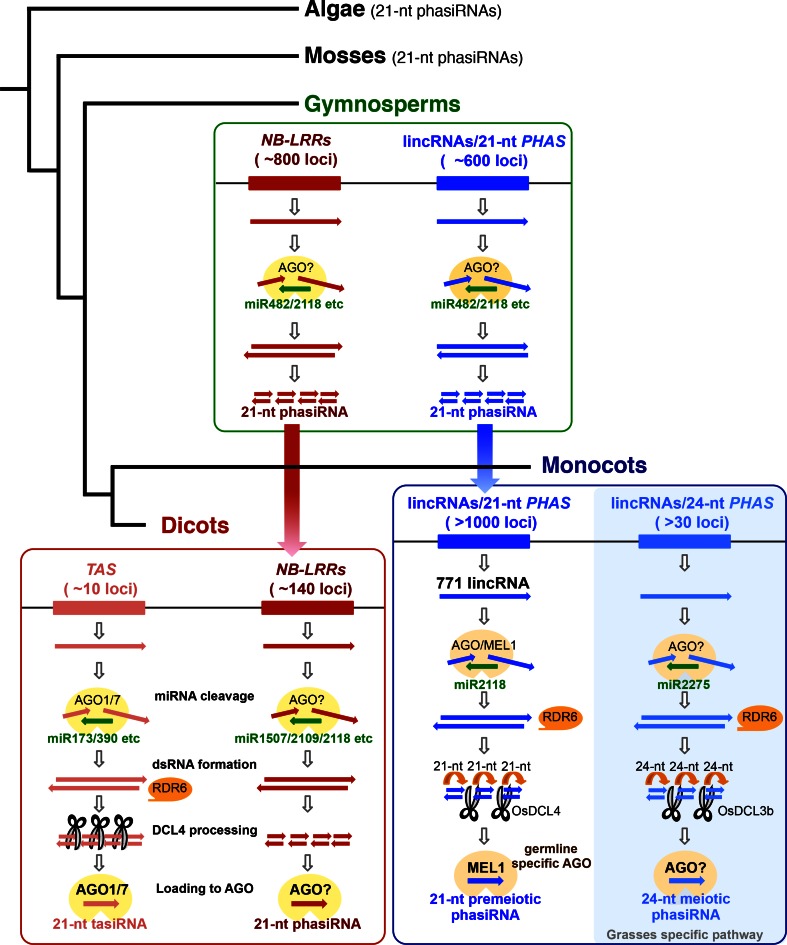

phasiRNAs are endogenous, eukaryote small RNAs that occur at intervals of 21–26 nucleotides. tasiRNAs, which are well-studied in Arabidopsis thaliana, play a role in leaf phase transition from juvenile to adult phases of vegetative stages (Peragine et al. 2004). In Arabidopsis thaliana tasiRNA biogenesis, single-stranded, non-coding RNAs are transcribed from TAS intergenic loci and cleaved by an AGO1/7-miRNA complex. RDR6 recruits cleaved TAS transcripts and forms dsRNAs. dsRNA formation follows DCL4-dependent processing into tasiRNAs 21-nt in length. Subsequently AGO1/7 associated with 21-nt tasiRNAs causes PTGS by cleaving target RNAs, such as transcripts of auxin response factor (ARF) family, pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) genes, and MYB transcription factors that include complement sequences recognized by AGO1/7-tasiRNAs complexes (Allen and Howell 2010; Allen et al. 2005; Vazquez et al. 2004; Yoshikawa et al. 2005), (Fig. 1). Recently, many types of phasiRNAs that are arranged at regular 21-, 22-, or 24-nt phased intervals have been identified in various plant species (International Brachypodium Initiative 2010; Johnson et al. 2009; Xia et al. 2015; Zhai et al. 2011; Zheng et al. 2015). Plant phasiRNA biogenesis generally involves 22-nt miRNA cleavage of a phasiRNA precursor RNA, dsRNA synthesis by RDR6, and processing by DCLs. This review focuses on the biogenesis and diversity of phasiRNAs in plants and animals.

Fig. 1.

A model for phasi/tasiRNA biogenesis in gymnosperms, dicots, and monocots. In plant phasi/tasiRNA biogenesis, (1) phasiRNA precursor transcripts are cleaved by 22-nt miRNA, (2) (RDR)-dependent dsRNAs are synthesized, (3) DCL-dependent processing results in phasiRNAs and (4) their loading onto AGO proteins. The phasiRNA pathway is conserved in gymnosperms, dicots, and monocots. In gymnosperms, there are miR482/miR2118-triggered phasiRNAs derived from both coding-RNAs (NB-LRRs, etc.) and non-coding RNAs (reproductive lincRNAs). The phasiRNA pathway, involving miR482/miR2118-triggered coding-RNAs (NB-LRRs), is also conserved in dicots. In contrast, miR482/miR2118-triggered phasiRNAs generated from reproductive lincRNAs are conserved in monocots

21-nt and 24-nt reproductive phasiRNAs in Poaceae

Numerous phasiRNAs are produced specifically during reproductive stages in the family Poaceae (International Brachypodium Initiative 2010; Johnson et al. 2009; Komiya et al. 2014; Song et al. 2012a, b; Ta et al. 2016; Zhai et al. 2015; Zheng et al. 2015). Johnson et al. (2009) reported that 21- and 24-nt phasiRNAs, which are specifically expressed in rice panicles, are derived from over 1000 intergenic regions, collectively termed PHAS loci. Most of the large intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs, PHAS) identified as precursor RNAs are single-stranded. They are transcribed with poly(A) tails without introns during early reproductive stages prior to meiosis in rice (Komiya et al. 2014). The precursor lincRNAs include 22-nt miR2118 recognition motifs, and the 24-nt phasiRNAs precursors also contain 22-nt miR2275 recognition motifs, where miR2118/miR2275 cleaves the precursor RNA to trigger the biogenesis of 21-nt/24-nt phasiRNAs. Subsequently, after dsRNA formation of cleaved RNAs, OsDCL4 generates 21-nt phasiRNAs or OsDCL3b produces 24-nt phasiRNAs (Johnson et al. 2009; Song et al. 2012a, b). DCLs-dependent phasiRNAs often form small RNA-duplexes with 2-bp overhangs at both 3′-termini. It is an intriguing subject how DCL4 and DCL3b recognize the differences of the dsRNAs derived from 21-nt PHAS or 24-nt PHAS in future.

Angiosperms develop primordial germ cells within reproductive organs that differentiate into meiocytes. Subsequently, meiocytes generate haploid gametophytes or spores via meiosis. MEIOSIS ARRESTED AT LEPTOTENE1 (MEL1) is a rice AGO protein that functions in the development of pre-meiotic germ cells and the progression of meiosis in both male and female organs. MEL1 binds dominantly to 21-nt phasiRNAs bearing a 5′-terminal cytosine, although AGOs interacting with 24-nt phasiRNAs remain unknown (Komiya et al. 2014; Nonomura et al. 2007), (Fig. 1). phasiRNA biogenesis in rice, such as 22-nt miRNA cleavage, OsDCL processing and AGO loading, is very similar to tasiRNA pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. In rice, expression of miR2118, lincRNAs and MEL1 coincides with premeiotic stages when germ cells differentiate, while this expression is very low in other stages. On the other hand, OsDCL4 regulates rice leaf development, spikelet formation, and stamen development in both vegetative and reproductive stages (Komiya et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2007; Nagasaki et al. 2007; Song et al. 2012a, b; Toriba et al. 2010). These results suggest that miR2118/lincRNAs/MEL1 regulates reproductive-specificities of 21-nt phasiRNA biogenesis, although functions of 21- and 24-nt phasiRNAs during premeiotic and meiotic stages in monocot reproduction are not well understood.

Photoperiod-sensitive male sterility (PSMS) is a phenomenon where particular rice strains show male sterility under long-day conditions, but are fertile under short-day conditions. Long-day-specific male-fertility-associated RNA (LDMAR) encodes the 1.2-kbp non-coding RNA that regulates PSMS. The abundant LDMAR transcript induces male sterility during long days, and is processed into small RNAs (Ding et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2012). Interestingly, the phenotype of vacuolation of sporophytic germ-cells in mel1 mutants is also observed in pollen mother cells (PMC) of pms3 mutants, although the male sterility phenotype in pms3 is distinct from that of mel1 in both male and female tissues. (Ding et al. 2012; Nonomura et al. 2007). Further study might reveal whether the function of reproductive specific lincRNAs generating phasiRNAs is related to LDMAR that produces small RNAs in PSMS.

Small RNAs interact with AGOs that function during plant reproduction

Ten AGO genes are present in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome, 19 in rice, and 17 in maize (Fei et al. 2013; Kapoor et al. 2008). Arabidopsis thaliana AGO5 (AtAGO5), related to rice MEL1, is believed to function in female gametogenesis, since a semi-dominant ago5-4 mutant is defective in the initiation of mega-gametogenesis (Borges et al. 2011; Tucker et al. 2012). AtAGO2 is involved in somatic DNA repair, and also in chiasma frequency in PMC (Oliver et al. 2014; Wei et al. 2012). AtAGO9, which interacts with 24-nt rasiRNAs, restricts the number of spore mother cells in somatic cells of an ovule, suppresses the activity of transposable elements, and is also responsible for the frequency of chromosome interlocks in meiosis in PMC (Oliver et al. 2014; Olmedo-Monfil et al. 2010). Maize AGO104, which is likely orthologous to AtAGO9 and AtAGO4, accumulates in somatic tissues surrounding female meiocytes and regulates condensation and disjunction of meiotic chromosomes (Singh et al. 2011), (Table 1). Thus, some plant AGOs have specific functions during reproduction, including germ cell development, meiosis, and gametogenesis. No PIWI-related proteins have been identified in plant genomes.

Table 1.

Small RNAs and AGOs in germlines of animals and plants

| Small RNA | Size (nt) | Processing | AGO | AGO function | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phased primary piRNAs | ~26 | Zucchini | PIWI, Aub | TE repression | Drosophila |

| piRNAs | 21 | ND | PRG-1 | Non-self RNAs including transgene repression | C. elegance |

| rasiRNAs | 24 | ND (DCL3?) | AGO9 | Germ cell fate repression and TE repression | A. thaliana |

| 1C-small RNAs | 21 | ND (DCL4?) | AGO5 | Female gametogenesis regulation | A. thaliana |

| phasiRNAs | 21 | OsDCL4 | MEL1 | Germ cell development and progression in meiosis | Rice |

| phasiRNAs | 24 | OsDCL3b/OsDCL5 | ND | ND | Rice |

| ND (rasiRNAs?) | ND | ND | AGO104 | Female germ cell development and chromosome condensation during meiosis | Maize |

| Premeiotic phasiRNAs | 21 | ND | ND (AGO5c?) | ND | Maize |

| Meiotic phasiRNAs | 24 | ND | ND (AGO18b?) | ND | Maize |

ND no data

In Arabidopsis thaliana, AGO1/7-tasiRNAs trans-regulate target RNAs via cleavage. MEL1-phasiRNA is localized mainly to the cytoplasm in PMC, so the leading hypothesis is that phasiRNAs may cause target-RNA cleavages in trans with MEL1 in the cytoplasm. However, a parallel analysis of RNA ends (PARE) degradome, a modified RACE that detects cleaved transcripts, and a transcriptome analysis of mel1 and dcl4 mutants, have failed so far to identify any cleaved target transcripts with complementary sequences of these phasiRNAs, indicating that MEL1-phasiRNAs may not trans-regulate targets (Komiya et al. 2014; Song et al. 2012a).

Although MEL1 is mainly localized in the cytoplasm of PMC, it is transiently localized in the nuclei of meiocytes at leptotene stage. In mel1 mutants, homologous chromosome synapsis and chromosome reprogramming via H3K9 (histone H3 lysine 9) modifications are depleted in early meiosis I (Komiya et al. 2014; Liu and Nonomura 2016). At the nearly same stage (zygotene) in maize meiocytes, DNA methylation increased at PHAS loci (Dukowic-Schulze et al. 2016). These results suggest that phasiRNAs regulate meiotic chromosome structure through epigenetic modifications to promote normal meiosis, although lincRNA expression was unaffected in panicles of mel1 mutants. The functions of 21- and 24-nt phasiRNAs, including MEL1-phasiRNAs in plants is an important subject for future studies in order to understand a molecular mechanism of monocots reproduction and a role of intergenic regions.

Phased piRNAs in animal germlines

piRNAs are germline-specific 23-30-nt small RNAs found in animals. piRNAs interacting with PIWI proteins repress expression of transposons to preserve genome integrity. Primary piRNAs are generated from single-stranded precursor transcripts derived from genomic transposons, and secondary piRNAs are amplified by the ping-pong pathway via PIWI proteins, Aubergene (Aub) and AGO3 in Drosophila germlines (Ghildiyal and Zamore 2009; Ishizu et al. 2012; Malone and Hannon 2009; Sato et al. 2015; Siomi et al. 2011; Thomson and Lin 2009). Recently, it was reported that phased piRNA generation is initiated by secondary piRNA-guided transcript cleavage, where every ~26-nt phaised piRNA are produced in the Zucchini endonuclease-dependent mechanism in Drosophila (Han et al. 2015; Mohn et al. 2015), (Table 1). During phased piRNA production, diverse piRNA sequences are produced, which allows quick adaptation to changes in transposon sequences. In C. elegans, Piwi-family AGO PRG-1 interacts with 21-nt piRNAs having uracil in the first position, and triggers RDR-dependent 22-nt RNA production having guanine in the first position, which suppresses transgenes (Gu et al. 2009; Ruby et al. 2006). Zucchini-dependent production of phased piRNAs indicates that phased piRNA biogenesis in animals is distinct from reproduction-specific phasiRNA biogenesis via miRNA-cleavage and DCLs processing in plants (Table 1).

Evolution and diversification of phasiRNAs in plants

In Medicago truncatula (Fabaceae), the 22-nt miR1507, miR2109, and miR2118 act as triggers to initiate generation of 21- and 22-nt phasiRNAs from mRNAs that encode nucleotide binding and leucine-rich repeat (NB-LRR) pathogen-defense genes and these 22-nt miRNAs are conserved in other legumes and nonlegumes, members of the family Solanaceae (Fei et al. 2015; Zhai et al. 2011). Besides NB-LRR genes, MYB transcription factors, PPR genes and a number of single- or low-copy genes, including Ca2 + ATPase, have been identified as coding RNA precursors that produce phasiRNAs in dicots (Arikit et al. 2014; Fei et al. 2013; Xia et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2012). These findings indicate that phasiRNAs are produced from protein-coding genes in dicots, in contrast to the Poaceae where non-coding RNAs are the main phasiRNA precursors (Brachypodium, rice and maize). The functions of phasiRNAs derived from the large gene families of MYB and PPR remain unknown. In contrast, NB-LRR gene families are regulated by both triggered-miRNAs and phasiRNAs generated from NB-LRRs, and the phasiRNAs also regulates in trans at other NB-LRR loci in legumes. Thus, NB-LRR-phasiRNA regulation shows a self-reinforcing network involving cis- or trans- regulation (Fei et al. 2013; Zhai et al. 2011).

A recent study using miR1507, miR2109 and miR2118 over expression lines and miRNA-targets, NB-LRRs, pairing analysis by validating the miRNA-precursor interaction, showed that miRNA levels limit the abundance of phasiRNAs (Fei et al. 2015). These results suggest that 22-nt miRNA abundance and/or efficiency of cleaving precursors RNAs are also key regulators for phasiRNA biogenesis.

In Norway spruce (Picea abies), over 2000 phasiRNA-produced loci (PHAS loci) have been identified, including ~800 loci derived from NB-LRRs and ~600 from non-coding RNAs, recognized by 41 species of miRNAs. Interestingly, miR418/miR2118 super-families in gymnosperms target both NB-LRR RNAs and reproductive non-coding RNAs, resulting in production of phasiRNAs derived from both NB-LRR RNAs and reproductive non-coding RNAs (Xia et al. 2015), (Fig. 1). These results suggest that dual miR482/miR2118-triggered phasiRNA biogenesis in gymnosperms emerged more than 300 million years ago, and that the pathways utilizing reproductive non-coding RNAs in monocots and the NB-LRR family-phasiRNA pathway in dicots may have been retained after the angiosperm lineage diverged (Fig. 1).

21-nt phasiRNAs are expressed in a wide range of plants, including algae, mosses, gymnosperms, basal angiosperms, monocots, and dicots. AGOs, DCLs, and RDRs required for phasiRNA biogenesis are also conserved from mosses to higher plants (Zheng et al. 2015), indicating that phasiRNA biogenesis is an ancient pathway in plants. In contrast, 24-nt phasiRNAs only exist in grass species (Arikit et al. 2013; Johnson et al. 2009; Zheng et al. 2015). Furthermore, miR2275 and DCL3b, involved in 24-nt meiotic phasiRNA production, are absent in dicot genomes, suggesting that the 24-nt phasiRNAs pathway originated recently in grasses or other monocots.

In maize anthers, two classes of phasiRNAs are expressed: 21-nt “premeiotic” phasiRNAs and 24-nt “meiotic” phasiRNAs, which are derived from a few hundred intergenic loci. LincRNAs (21-nt PHAS) and 21-nt phasiRNAs accumulate in pollen sacs, and miR2118 localizes in epidermis of premeiotic anthers in maize and African rice. In contrast, lincRNAs (24-nt PHAS), miR2275, and 24-nt phasiRNAs are expressed in tapetum and meiocytes in meiotic anthers (Ta et al. 2016; Zhai et al. 2015). Expression profiles of maize genes show that maize AGO5c, related to rice MEL1, is expressed at premeiotic stages and the expression timing and sites of AGO18b are similar to 24-nt meiotic phasiRNAs, suggesting that these AGOs may be candidates for binding to 21-nt premeiotic phasiRNAs/24-nt meiotic phasiRNAs (Table 1). Intriguingly, the two types of grass phasiRNAs are analogous to the mammalian piRNA classes, i.e. premeiotic 26 to 27-nt piRNAs and meiotic 29~30-nt piRNAs (Zhai et al. 2014, 2015). These two classes of small RNAs involved in male development may have resulted from convergent evolution of the reproductive small RNA pathway, which shares developmental timing and special expression patterns in male reproductive tissues in both plant and animal lineages. During land plant evolution, spatio-temporal regulation of phasiRNA biogenesis might have been helpful for plants to adapt to environmental changes and various stresses. Further studies to elucidate biogenesis and function of phasiRNAs would help us to understand their contribution to plant development and defence responses.

Concluding remarks

Transcriptomic analyses of small RNAs have revealed that numerous kinds of phasiRNAs are expressed in plants. phasiRNA biogenesis, including 22-nt miRNA-cleavage, RDR-dsRNA synthesis, and DCL-processing, is conserved in gymnosperms, monocots, and dicots, suggesting its essential role in plants. In many cases, however, molecular mechanisms of action and phasiRNA functions remain unclear. Open questions include: (1) How are numerous lincRNAs regulated during specific developmental stages and pathogenesis? (2) What is the molecular mechanism of lincRNA cleavage by 22-nt miRNAs? (3) What is the primary role of phasiRNAs in plants? Answering these questions will require experiments exploiting technologies such as genomics/epigenetics using non-coding RNA mutants, cell sorting, biochemistry, and structural analysis. Such studies are expected to help us to understand the significance of non-coding regions in both plants and animals.

Acknowledgements

I thank Drs. Hidetoshi Saze and Kenji Osabe for helpful comments and discussions during preparation of this manuscript. I also thank Dr. Steven D. Aird for technical editing. I thank all of the members of the Science and Technology Group (STG) and the Plant Epigenetics Unit for the helpful discussions.

Funding

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. 14456270 and 15645449. Generous support for the Science and Technology Group was provided by OIST Graduate University.

References

- Allen E, Howell MD. miRNAs in the biogenesis of trans-acting siRNAs in higher plants. Semi Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Carrington JC. microRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell. 2005;121:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikit S, Zhai J, Meyers BC. Biogenesis and function of rice small RNAs from non-coding RNA precursors. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikit S, Xia R, Kakrana A, Huang K, Zhai J, Yan Z, Valdes-Lopez O, Prince S, Musket TA, Nguyen HT, Stacey G, Meyers BC. An atlas of soybean small RNAs identifies phased siRNAs from hundreds of coding genes. Plant Cell. 2014;26:4584–4601. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.131847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F, Pereira PA, Slotkin RK, Martienssen RA, Becker JD. MicroRNA activity in the Arabidopsis male germline. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:1611–1620. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel SE, Martienssen RA. RNA interference in the nucleus: roles for small RNAs in transcription, epigenetics and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:100–112. doi: 10.1038/nrg3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Hannon GJ. Small RNA sorting: matchmaking for Argonautes. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Lu Q, Ouyang Y, Mao H, Zhang P, Yao J, Xu C, Li X, Xiao J, Zhang Q. A long noncoding RNA regulates photoperiod-sensitive male sterility, an essential component of hybrid rice. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2654–2659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121374109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukowic-Schulze S, Sundararajan A, Ramaraj T, Kianian S, Pawlowski WP, Mudge J, Chen C. Novel meiotic miRNAs and indications for a role of phasiRNAs in meiosis. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:762. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Q, Xia R, Meyers BC. Phased, secondary, small interfering RNAs in posttranscriptional regulatory networks. Plant Cell. 2013;25:2400–2415. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.114652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Q, Li P, Teng C, Meyers BC. Secondary siRNAs from Medicago NB-LRRs modulated via miRNA-target interactions and their abundances. Plant J. 2015;83:451–465. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:94–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Shirayama M, Conte D, Jr, Vasale J, Batista PJ, Claycomb JM, Moresco JJ, Youngman EM, Keys J, Stoltz MJ, Chen CC, Chaves DA, Duan S, Kasschau KD, Fahlgren N, Yates JR, 3rd, Mitani S, Carrington JC, Mello CC. Distinct argonaute-mediated 22G-RNA pathways direct genome surveillance in the C. elegans germline. Mol Cell. 2009;36:231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AJ, Baulcombe DC. A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science. 1999;286:950–952. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BW, Wang W, Li C, Weng Z, Zamore PD. Noncoding RNA. piRNA-guided transposon cleavage initiates Zucchini-dependent, phased piRNA production. Science. 2015;348:817–821. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Brachypodium Initiative Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature. 2010;463:763–768. doi: 10.1038/nature08747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizu H, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Biology of PIWI-interacting RNAs: new insights into biogenesis and function inside and outside of germlines. Gene Dev. 2012;26:2361–2373. doi: 10.1101/gad.203786.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakawa H, Tomari Y. The functions of microRNAs: mRNA decay and translational repression. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:651–665. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C, Kasprzewska A, Tennessen K, Fernandes J, Nan GL, Walbot V, Sundaresan V, Vance V, Bowman LH. Clusters and superclusters of phased small RNAs in the developing inflorescence of rice. Genome Res. 2009;19:1429–1440. doi: 10.1101/gr.089854.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor M, Arora R, Lama T, Nijhawan A, Khurana JP, Tyagi AK, Kapoor S. Genome-wide identification, organization and phylogenetic analysis of Dicer-like, Argonaute and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene families and their expression analysis during reproductive development and stress in rice. BMC Genom. 2008;9:451. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya R, Ohyanagi H, Niihama M, Watanabe T, Nakano M, Kurata N, Nonomura K. Rice germline-specific Argonaute MEL1 protein binds to phasiRNAs generated from more than 700 lincRNAs. Plant J. 2014;78:385–397. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Nonomura KI. Histone H3 modifications are widely reprogrammed during male meiosis I in rice dependently on MEL1 Argonaute protein. J Cell Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1242/jcs.184937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Chen Z, Song X, Liu C, Cui X, Zhao X, Fang J, Xu W, Zhang H, Wang X, Chu C, Deng X, Xue Y, Cao X. Oryza sativa dicer-like4 reveals a key role for small interfering RNA silencing in plant development. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2705–2718. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CD, Hannon GJ. Small RNAs as guardians of the genome. Cell. 2009;136:656–668. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke M, Kanno T, Daxinger L, Huettel B, Matzke AJ. RNA-mediated chromatin-based silencing in plants. Cur Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn F, Handler D, Brennecke J. Noncoding RNA. piRNA-guided slicing specifies transcripts for Zucchini-dependent, phased piRNA biogenesis. Science. 2015;348:812–817. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki H, Itoh J, Hayashi K, Hibara K, Satoh-Nagasawa N, Nosaka M, Mukouhata M, Ashikari M, Kitano H, Matsuoka M, Nagato Y, Sato Y. The small interfering RNA production pathway is required for shoot meristem initiation in rice. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14867–14871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704339104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R. Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in trans. Plant Cell. 1990;2:279–289. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura K, Morohoshi A, Nakano M, Eiguchi M, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Kurata N. A germ cell specific gene of the ARGONAUTE family is essential for the progression of premeiotic mitosis and meiosis during sporogenesis in rice. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2583–2594. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C, Santos JL, Pradillo M. On the role of some ARGONAUTE proteins in meiosis and DNA repair in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:177. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo-Monfil V, Duran-Figueroa N, Arteaga-Vazquez M, Demesa-Arevalo E, Autran D, Grimanelli D, Slotkin RK, Martienssen RA, Vielle-Calzada JP. Control of female gamete formation by a small RNA pathway in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2010;464:628–632. doi: 10.1038/nature08828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragine A, Yoshikawa M, Wu G, Albrecht HL, Poethig RS. SGS3 and SGS2/SDE1/RDR6 are required for juvenile development and the production of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Gene Dev. 2004;18:2368–2379. doi: 10.1101/gad.1231804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano N, Macino G. Quelling: transient inactivation of gene expression in Neurospora crassa by transformation with homologous sequences. Mol Micro. 1992;6:3343–3353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby JG, Jan C, Player C, Axtell MJ, Lee W, Nusbaum C, Ge H, Bartel DP. Large-scale sequencing reveals 21U-RNAs and additional microRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in C. elegans. Cell. 2006;127:1193–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Iwasaki YW, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Tudor-domain containing proteins act to make the piRNA pathways more robust in Drosophila. Fly. 2015;9:86–90. doi: 10.1080/19336934.2015.1128599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Goel S, Meeley RB, Dantec C, Parrinello H, Michaud C, Leblanc O, Grimanelli D. Production of viable gametes without meiosis in maize deficient for an ARGONAUTE protein. Plant Cell. 2011;23:443–458. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:246–258. doi: 10.1038/nrm3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Li P, Zhai J, Zhou M, Ma L, Liu B, Jeong DH, Nakano M, Cao S, Liu C, Chu C, Wang XJ, Green PJ, Meyers BC, Cao X. Roles of DCL4 and DCL3b in rice phased small RNA biogenesis. Plant J. 2012;69:462–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Wang D, Ma L, Chen Z, Li P, Cui X, Liu C, Cao S, Chu C, Tao Y, Cao X. Rice RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 6 acts in small RNA biogenesis and spikelet development. Plant J. 2012;71:378–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ta KN, Sabot F, Adam H, Vigouroux Y, De Mita S, Ghesquiere A, Do NV, Gantet P, Jouannic S. miR2118-triggered phased siRNAs are differentially expressed during the panicle development of wild and domesticated African rice species. Rice. 2016;9:10. doi: 10.1186/s12284-016-0082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson T, Lin H. The biogenesis and function of PIWI proteins and piRNAs: progress and prospect. Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:355–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toriba T, Suzaki T, Yamaguchi T, Ohmori Y, Tsukaya H, Hirano HY. Distinct regulation of adaxial-abaxial polarity in anther patterning in rice. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1452–1462. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker MR, Okada T, Hu Y, Scholefield A, Taylor JM, Koltunow AM. Somatic small RNA pathways promote the mitotic events of megagametogenesis during female reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Development. 2012;139:1399–1404. doi: 10.1242/dev.075390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F, Vaucheret H, Rajagopalan R, Lepers C, Gasciolli V, Mallory AC, Hilbert JL, Bartel DP, Crete P. Endogenous trans-acting siRNAs regulate the accumulation of Arabidopsis mRNAs. Mol Cell. 2004;16:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Ba Z, Gao M, Wu Y, Ma Y, Amiard S, White CI, Rendtlew Danielsen JM, Yang YG, Qi Y. A role for small RNAs in DNA double-strand break repair. Cell. 2012;149:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia R, Zhu H, An YQ, Beers EP, Liu Z. Apple miRNAs and tasiRNAs with novel regulatory networks. Gen Biol. 2012;13:R47. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia R, Xu J, Arikit S, Meyers BC. Extensive families of miRNAs and PHAS loci in Norway spruce demonstrate the origins of complex phasiRNA networks in seed plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:2905–2918. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M, Peragine A, Park MY, Poethig RS. A pathway for the biogenesis of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Gen Dev. 2005;19:2164–2175. doi: 10.1101/gad.1352605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai J, Jeong DH, De Paoli E, Park S, Rosen BD, Li Y, Gonzalez AJ, Yan Z, Kitto SL, Grusak MA, Jackson SA, Stacey G, Cook DR, Green PJ, Sherrier DJ, Meyers BC. MicroRNAs as master regulators of the plant NB-LRR defense gene family via the production of phased, trans-acting siRNAs. Gen Dev. 2011;25:2540–2553. doi: 10.1101/gad.177527.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai L, Sun W, Zhang K, Jia H, Liu L, Liu Z, Teng F, Zhang Z. Identification and characterization of Argonaute gene family and meiosis-enriched Argonaute during sporogenesis in maize. Int Plant Biol. 2014;56:1042–1052. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai J, Zhang H, Arikit S, Huang K, Nan GL, Walbot V, Meyers BC. Spatiotemporally dynamic, cell-type-dependent premeiotic and meiotic phasiRNAs in maize anthers. Proc Nat Aca Sci USA. 2015;112:3146–3151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418918112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Wang Y, Wu J, Ding B, Fei Z. A dynamic evolutionary and functional landscape of plant phased small interfering RNAs. BMC Biol. 2015;13:32. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Liu Q, Li J, Jiang D, Zhou L, Wu P, Lu S, Li F, Zhu L, Liu Z, Chen L, Liu YG, Zhuang C. Photoperiod- and thermo-sensitive genic male sterility in rice are caused by a point mutation in a novel noncoding RNA that produces a small RNA. Cell Res. 2012;22:649–660. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Xia R, Zhao B, An YQ, Dardick CD, Callahan AM, Liu Z. Unique expression, processing regulation, and regulatory network of peach (Prunus persica) miRNAs. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]