Abstract

The plant lectins derived from Galanthus nivalis (Snowdrop) (GNA) and Hippeastrum hybrid (Amaryllis) (HHA) selectively inhibited a wide variety of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV-2 strains and clinical (CXCR4- and CCR5-using) isolates in different cell types. They also efficiently inhibited infection of T lymphocytes by a variety of mutant virus strains. GNA and HHA markedly prevented syncytium formation between persistently infected HUT-78/HIV cells and uninfected T lymphocytes. The plant lectins did not measurably affect the antiviral activity of other clinically approved anti-HIV drugs used in the clinic when combined with these drugs. Short exposure of the lectins to cell-free virus particles or persistently HIV-infected HUT-78 cells markedly decreased HIV infectivity and increased the protective (microbicidal) activity of the plant lectins. Flow cytometric analysis and monoclonal antibody binding studies and a PCR-based assay revealed that GNA and HHA do not interfere with CD4, CXCR4, CCR5, and DC-SIGN and do not specifically bind with the membrane of uninfected cells. Instead, GNA and HHA likely interrupt the virus entry process by interfering with the virus envelope glycoprotein. HHA and GNA are odorless, colorless, and tasteless, and they are not cytotoxic, antimetabolically active, or mitogenic to human primary T lymphocytes at concentrations that exceed their antivirally active concentrations by 2 to 3 orders of magnitude. GNA and HHA proved stable at high temperature (50°C) and low pH (5.0) for prolonged time periods and can be easily formulated in gel preparations for microbicidal use; they did not agglutinate human erythrocytes and were not toxic to mice when administered intravenously.

Men and particularly women are at high risk to acquire infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) through sexual intercourse. HIV may enter the blood circulation as cell-free virus but also through virus-infected cells that express virus-specific antigens on their membrane and that either produce new virus particles and/or may fuse with uninfected CD4/CXCR4- or CD4/CCR5-expressing target cells. Genital mucosal transmission of HIV is an important route of new HIV infection in individuals. An efficient preventive measure should be aimed at inhibiting the spread of both cell-associated and free virus.

The binding of HIV to its target cells and the fusion between HIV-infected and noninfected T4 lymphocytes requires complex multistep specific interactions of the viral envelope glycoproteins gp120 and gp41 with the primary cell surface receptor CD4 and the chemokine receptor/HIV coreceptor CCR5 and/or CXCR4 (12, 27, 29, 30). HIV type 1 (HIV-1) strains or clinical isolates that use CCR5 or CXCR4 as their coreceptor are termed R5 and X4 viruses, respectively, whereas R5/X4 viruses can use both chemokine receptors to enter the cells. The carbohydrate portions of gp120 and gp41 represent an important part of these molecules and are involved in their interaction with CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5. Therefore, compounds that interact with the sugar part of gp120 and/or gp41 should be able to efficiently block virus transmission by blocking HIV adsorption to its receptor(s) and/or HIV-mediated cell-cell fusion.

Virus adsorption and fusion inhibitors may be ideal candidates as microbicides; since they do not require uptake by the cells, they are active as such and thus need not to be metabolized to be antivirally active. A variety of adsorption inhibitors that act through binding to the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 (35) (i.e., polysulfates, polysulfonates, polycarboxylates, and negatively charged albumins) have been described (for an overview, see reference 10). Also, virus entry inhibitors that block the viral coreceptor CXCR4 (i.e., the bicyclam AMD3100 derivatives and the natural CXCR4 chemokine ligand, SDF-1) or CCR5 (i.e., the quaternary ammonium derivative TAK-779, the natural CCR5 ligands RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β, as well as SCH-C), and virus-cell fusion inhibitors that act through binding to the viral transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 (i.e., T-20, previously called DP-178) have been reported (2, 10, 24, 36). Besides the chemokines and T20 derivatives, also cyanovirin N is a peptidic substance able to prevent the interaction of gp120 with its target cells (7, 31).

More than a decade ago, plant lectins were reported to inhibit HIV replication in lymphocyte cell cultures through inhibition of virus/cell fusion (4, 19, 20, 29). There exists a wide variety of specific sugar-recognizing plant lectins, among which mannose-binding lectins are the most potent inhibitors of HIV replication in cell culture (4, 5). Initially, it was reported that plant lectins inhibit virus replication by preventing virus adsorption (binding) (32), but it was later shown that they rather prevent fusion of HIV particles with their target cells (4, 5). Systemic use of plant lectins to inhibit HIV infection may be questionable in terms of their antigenic (immunogenic) properties and limited plasma half-life (rapid clearance) due to their peptidic nature. However, local (intravaginal) application as a gel or cream formulation may avoid the above-mentioned disadvantages and may open novel perspectives to develop the lectins as microbicides (virucides) to prevent HIV transmission and infection.

In the present study, we evaluated two highly mannose-specific plant lectins for their potential to prevent HIV infection and spread by both virus-to-cell and cell-to (virus-infected)-cell contact. Several aspects and parameters that are required for a successful microbicide were investigated. It was concluded that the mannose-specific lectins from Galanthus nivalis and Hippeastrum hybrid (GNA and HHA, respectively) of the Amaryllidaceae plant family are promising candidate drugs for further (pre)clinical studies to investigate their usefulness as microbicides against HIV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Test compounds.

The mannose-specific plant lectins GNA and HHA were derived and purified from the bulbs of these plants, as described previously (23, 41-43). UC-781 was obtained from Crompton, Ltd. (Middlebury, Conn.). Tenofovir was from Gilead Sciences (Foster City, Calif.), AMD3100 was from AnorMed (Langley, British Columbia, Canada), and dextran sulfate-5000 and pentosan polysulfate were from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Lamivudine and amprenavir were kindly provided by J.-P. Kleim (GlaxoSmithKline, Stevenage, United Kingdom). T20 was kindly provided by AIDS Research Alliance (Los Angeles, Calif.), and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-GNA was obtained from EY Laboratories, Inc.

Cells.

Human T-lymphocytic CEM and Sup-T1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). MT-4 cells were kindly provided by L. Montagnier (Pasteur Institute, Paris, France); Molt4/clone 8 cells were from N. Yamamoto (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan), and persistently infected HUT-78/HIV cells were obtained by exposing HUT-78 cell cultures to HIV-1(IIIB) or HIV-2(ROD) for 3 to 4 weeks. All cell lines mentioned above were cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; BioWittaker Europe, Verviers, Belgium), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 0.075 M NaHCO3. Human astroglioma U87 cells transfected with CD4 (U87.CD4) and CD4/CCR5 (U87.CD4.CCR5) were kindly provided by D. R. Littman (Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine, New York University Medical Center) and cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.01 M HEPES buffer (Invitrogen), and 0.2 mg of Geneticin (G-418 sulfate; Invitrogen)/ml. The construction of U87.CD4.CXCR4 and U87.CD4.CCR5 cells has been described before (12, 21).

Viruses.

HIV-1(IIIB and RF) and HIV-1(Ba-L) were provided by R. C. Gallo and M. Popovic (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health), and HIV-2(ROD and EHO) was from L. Montagnier (Pasteur Institute, Paris, France). The T-tropic molecular clone NL4.3 was obtained from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease AIDS Reagent Program. The clinical HIV-1 isolates 4, 15, 16, 19, 32, 33, 35, and 40 were derived from HIV-1-infected individuals and characterized for their coreceptor use in U87.CD4.CXCR4 and U87.CD4.CCR5 cells. The simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)mac251 strain was originally isolated from macaques (9). Feline immunodeficiency virus type 113a (FIV-113a) was prepared from the supernatant of chronically FIV-infected Crandell feline kidney (CRFK) cell cultures (15).

Antiretrovirus assays.

The methodology of the anti-HIV assays has been described previously (3, 40). Briefly, MT-4 or CEM cells (4.5 × 105 cells/ml) were suspended in fresh culture medium and infected with HIV-1, HIV-2, or SIV at 100 times the virus dose infective for 50% of the cell cultures (CCID50) per ml of cell suspension. Then, 100 μl of the infected cell suspension was transferred to 96-well microplate wells, mixed with 100 μl of the appropriate dilutions of the test compounds (i.e., final concentrations of 200, 40, 8, 1.6, 0.32, and 0.062 μg/ml), and further incubated at 37°C. In the experiments in which the plant lectins were combined with other anti-HIV drugs, 50 μl of an appropriate concentration of these test compounds was added to the HIV-1-infected cell suspension that contained a variety of lectin concentrations. After 4 to 5 days, giant cell formation was recorded microscopically in the CEM cell cultures. The MT-4 cell cultures were treated with trypan blue, and the number of viable cells was determined. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) corresponded to the compound concentrations required to prevent syncytium formation by 50% in the virus-infected CEM cell cultures or the compound concentrations required to reduce the amount of living cells by 50% in the MT-4 cell cultures.

Buffy coat preparations from healthy donors were obtained from the Blood Bank in Leuven. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation over Lymphoprep (density = 1.077 g/ml; Nycomed, Oslo, Norway). The PBMC were transferred to RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (BioWhittaker Europe) and 2 mM l-glutamine and then stimulated for 3 days with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Murex Biotech Limited, Dartford, United Kingdom) at 2 μg/ml. The activated cells (PHA-stimulated blasts) were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and viral infections were carried out as described by Cocchi et al. (8). HIV-infected or mock-infected PHA-stimulated blasts were cultured in the presence of 10 ng of interleukin-2/ml and various concentrations of GNA and HHA. Supernatant was collected at days 8 to 10, and HIV-1 core antigen in the culture supernatant was analyzed by the p24 core antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; DuPont-Merck Pharmaceutical Co., Wilmington, Del.).

The anti-FIV assays were performed essentially as described previously (16, 40). A total of 5 × 103 CRFK cells were seeded onto 96-well tissue culture plates. Cells were cultured with 200 μl of culture medium/well containing 5% fetal calf serum in the presence of fourfold dilutions of the antiviral drug. After a 1-h incubation period at 37°C, cells were infected with 100 TCID50 of the Petaluma strain FIV-Cr113 in the presence of the various concentrations of the drug. After 2 h the medium was removed and new medium containing the appropriate drug concentrations was added. FIV replication was determined after 6 days in the cell culture supernatants by using a FIV p24 ELISA. The cytotoxicity of the drugs was measured by using an MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay. The EC50 values and the drug concentrations reducing the number of viable mock-infected cells by 50% were calculated from the data obtained.

Antiviral assays.

The antiviral assays, other than the antiretrovirus assays, were based on inhibition of virus-induced cytopathogenicity in HeLa cells (for vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), poliovirus type 1, coxsackievirus, and respiratory syncytial virus), Vero cells (for Sindbis virus, parainfluenza virus type 3, Semliki forest virus, coxsackievirus type B4, and reovirus type 1), or human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts (for VSV) according to previously established procedures (11).

Cocultivation assays.

Persistently HIV-1- or HIV-2-infected HUT-78 cells (designated HUT-78/HIV-1 and HUT-78/HIV-2, respectively) were washed to remove free virus from the culture medium, and 5 × 104 cells (50 μl) were transferred to 96-well microtiter plates (Sterilin). Then, 5 × 104 Molt4 (clone 8) or Sup-T1 cells (50 μl), along with an appropriate concentration of test compound (100 μl), were added to each well. The mixed cell cultures were cultured at 37°C in a CO2-controlled atmosphere. The first syncytia arose after about 6 h of cocultivation. After 16 to 20 h, marked syncytium formation was noted, and the number of syncytia was determined under a microscope.

Preexposure of cell-free HIV-1, noninfected MT-4 and Sup-T1 cells or persistently infected HUT-78/HIV-1 cells to the plant lectins prior to infection or cocultivation assays.

In a first set of experiments, a concentrated cell-free HIV-1(IIIB) preparation (100 μl) was exposed to 100 μl of 100, 40, 10, and 4 μg of HHA or GNA/ml for 2 h at room temperature (final lectin concentrations of 50, 20, 5, and 2 μg/ml). Then, the drug-exposed virus suspension was diluted such that a final 1,000-fold dilution of virus and lectin were exposed to MT-4 cell cultures (40,000 cells/200-μl well). At day 5 postinfection, virus-induced destruction of the MT-4 cell cultures was recorded microscopically by counting the living cells by using trypan blue dye exclusion. Also, 5 × 105 MT-4 cells in 1 ml of cell culture medium were preexposed to final concentrations of 100, 40, 10, and 4 μg of HHA or GNA/ml for 2 h. Then, 9 ml of drug-free medium was added to these cell suspensions, and the cells were centrifuged. Next, 9.8 ml of supernatant was removed, and the residual cells (in 200 μl of medium) were resuspended in 800 μl of medium (final dilution, 50-fold). From this cell suspension, 100 μl of cells was added to 100 μl of HIV-1(IIIB) (equivalent of 100 CCID50). Thus, the final lectin concentrations left over in the virus-exposed cell suspensions were 1, 0.4, 0.1, and 0.04 μg/ml. At day 5 postinfection, the antiviral activity of the plant lectins was determined as described above. The cell cultures that were infected with untreated HIV-1(IIIB) and that were not preincubated with the plant lectins received a final concentration of 2, 0.5, 0.2, and 0.05 μg of the plant lectins/ml.

In a second set of experiments, concentrated HUT-78/HIV-1 or Sup-T1 cell suspensions in 1 ml of cell culture medium were preexposed to a final concentration of HHA and GNA at 2,000, 400, 100, and 25 μg/ml for 2 h, after which 9 ml of cell culture medium was added to the cell cultures (lectin dilution, 10-fold). After centrifugation, 9,900 μl of supernatant was removed, and cells (in 100 μl) were resuspended in 0.9 ml of culture medium (final lectin concentration, 1:100). Then, 100 μl (105 cells) of drug-preexposed HUT-78/HIV-1 cells was mixed with 100 μl of non-drug-exposed Sup-T1 cells or, vice versa, drug-preexposed Sup-T1 cells were mixed with non-drug-exposed HUT-78/HIV-1 cells (final lectin concentration, 1:200). Syncytium formation was examined microscopically at 20 to 24 h after the start of the cocultivation and compared to cocultures that were not preexposed to the plant lectins but to which different concentrations (20, 4, and 0.8 μg/ml) of HHA and GNA were added at the time of initiation of the cocultivation.

Exposure of HIV-1(IIIB)-infected cell cultures to fixed concentrations of plant lectins.

CEM cell cultures (105 cells/ml) were seeded in 48-well microtiter plates and infected with HIV-1(IIIB) (100 CCID50/ml) in the presence of fixed concentrations of HHA (i.e., 25, 6.2, 1.25, and 0.50 μg/ml). Every 4 to 5 days cells were subcultured by transferring 50 μl of the cell suspension or 200 μl of cell culture supernatant to 950 or 800 μl of cell culture medium, respectively, containing fresh CEM cells at 105 cells/ml (final cell number). The compound concentrations were kept constant through all subcultivations. After 10 subcultivations, the cell cultures in which no cytopathicity of the virus was microscopically visible were further cultivated in the absence of drug for at least an additional 10 subcultivations. To assure whether these virus cultures did not contain any residual virus anymore, a PCR to amplify the reverse transcriptase (RT) gene of HIV-1(IIIB) was performed on the cultures as previously described (6).

Exposure of HHA-containing gel preparations to HIV-1-infected CEM cell cultures and cocultures of persistently HIV-1-infected CEM/HIV-1 and uninfected Sup-T1 cells.

A 3% HHA gel ointment was prepared and added to cell culture medium. Fivefold dilutions of the gel preparation were performed and administered to HIV-1-infected CEM cell cultures or to cocultures of persistently HIV-1-infected CEM/HIV-1 and uninfected Sup-T1 cells in 96-well microtiter plates. The inhibitory activity of HHA-containing gel and free HHA on syncytium formation between CEM/HIV-1 and Sup-T1 cells (after 24 h) or HIV-1-induced cytopathicity in HIV-1-infected CEM cell cultures (after 4 days) was recorded.

PCR-based HIV entry assay.

The U87.CD4.CXCR4 and U87.CD4.CCR5 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 5 × 104 cells per well and incubated overnight. Virus stocks (diluted to a p24 antigen titer of 10,000 pg/ml) were treated with 500 U of RNase-free DNase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals)/ml for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were preincubated with the test compounds for 30 min at 37°C. The cells in each well were then infected with 1,000 pg of HIV-1 p24 (X4 strain NL4.3 for U87.CD4.CXCR4 cells and R5 strain Ba-L for U87.CD4.CCR5 cells). To control for possible residual contamination of the viral inoculum with viral DNA, a parallel infection was carried out on the nontransfected U87.CD4 cells. After incubation at 37°C for 2 h, the medium was aspirated, the cells were washed once with PBS, and total DNA was extracted from the infected cells by using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen). The DNA was eluted from the QIAamp spin columns in a final volume of 250 μl of elution buffer. Then, 10 μl of each DNA sample was subjected to 35 cycles of HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) R/U5-specific and 32 cycles of β-actin-specific PCR on a Biometra T3 thermocycler. Each cycle comprised a 45-s denaturation step at 95°C, a 45-s annealing step at 61°C, and a 45-s extension step at 72°C. In preliminary experiments, the exponential range of the PCR amplification curve was determined for both the HIV-1 LTR R/U5 and the β-actin PCRs by varying the amount of input DNA and the number of PCR cycles. Based on these experiments, appropriate conditions were chosen to perform the PCRs. We used the following primers (21): LTR R/U5 sense primer (5′-GGCTAACTAGGGAACCCACTG-3′; nucleotides 496 to 516, according to the HIV-1 HXB-2 DNA sequence), LTR R/U5 antisense primer (5′-CTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGAC-3′; nucleotides 612 to 635, yielding a 140-bp DNA fragment), β-actin sense primer (5′-TCTGGCGGCACCACCATGTACC-3′; nucleotides 2658 to 2679), and β-actin antisense primer (5′-CGATGGAGGGGCCGGACTCG-3′; nucleotides 2961 to 2980, yielding a 323-bp DNA fragment). The reaction mixtures contained PCR buffer (supplied with the enzyme); 200 μM concentrations (each) of dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP (Life Technologies); 0.4 μM concentrations (each) of the forward and reverse primers; and 0.5 U of SuperTaq DNA polymerase (HT Biotechnology, Cambridge, United Kingdom) in a total volume of 25 μl. After gel electrophoresis with a 2% agarose gel, the amplified DNA fragments were visualized by using ethidium bromide.

Antibody stainings and flow cytometry.

Human T-lymphoid MT-4 cells were washed once with PBS containing 2% FBS and then preincubated with HHA or GNA at 20 μg/ml for 30 min on ice. After centrifugation and washing with PBS containing 2% FBS, the cells were incubated for 30 min on ice with a panel of different anti-human CXCR4 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs)—clones 12G5 and 2B11 (BD Pharmingen) and 44717.111 (R&D Systems Europe; phycoerythrin [PE] conjugated), anti-human CD4 MAbs [i.e., clones SK3(Leu3a) and L120(CD4 v4), PE conjugated],OKT4 and OKT4A (FITC conjugated [Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Raritan, N.J.]), and anti-HIV-1 gp120 MAbs (NEA 9284 [E. I. du Pont de Nemours])—in PBS containing 2% FBS. Also, HHA- and GNA-pretreated persistently infected HUT-78/HIV-1(IIIB) cells were incubated for 60 min at 37°C with an anti-HIV-1 gp120 MAb (NEA 9284 unconjugated [E. I. du Pont de Nemours]) and were subsequently incubated for 45 min at room temperature with a secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G, PE conjugated [Caltag Laboratories]) in PBS containing 2% FBS. After the antibody staining, the cell samples were washed twice with PBS, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and analyzed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer equipped with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). As a negative control for nonspecific background staining, the cells were stained in parallel with Simultest Isotype control MAb (Becton Dickinson).

Measurement of intracellular calcium signaling.

The suspension Sup-T1 T-lymphocyte cell line was used in stationary growth phase (3 days after 2/3 subcultivation). Adherent CCR5-transfected U87.CD4 cells were seeded in 0.1% gelatin-coated black-wall 96-well microplates at 2 × 104 cells per well the day before the experiment. On the day of the experiment, cells were loaded with the fluorescent calcium indicator Fluo-3 (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) at 4 μM for 45 min at room temperature (Sup-T1 cells) or at 37°C (U87.CD4.CCR5 cells). After loading, the cells were washed thoroughly with calcium flux assay buffer (Hanks balanced salt solution containing 20 mM HEPES and 0.2% bovine serum albumin (pH 7.4) to remove extracellular dye. The cells were then preincubated with the plant lectins at a concentration of 10 μg/ml at 37°C for 10 min, and then the intracellular calcium signaling in response to 40 ng of SDF-1/ml (Sup-T1 cells) or 40 ng of RANTES/ml (U87.CD4.CCR5 cell) was measured in all 96 wells simultaneously as a function of time by using a fluorometric imaging plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

Toxicity assays. (i) Cell proliferation.

Murine leukemia L1210 and mammary carcinoma FM3A cells, human lymphocytic Molt4/C8 and CEM cells, and cervix carcinoma HeLa cells were seeded in 96-well microtiter plates at ca. 5 × 104 cells/200-μl well in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium in the presence of various concentrations (2000, 400, 80, 16, 3.2, and 0.62 μg/ml) of GNA and HHA. The cell cultures were cultivated for 48 h (L1210 and FM3A), 72 h (Molt4/C8 and CEM), or 96 h (HeLa) at 37°C in a CO2-controlled atmosphere. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were counted in a Coulter Counter (Analis, Ghent, Belgium).

(ii) Mitogenic activity assays.

Human PBMC were isolated from buffy coats and brought in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 2 mM l-glutamine. The cell cultures were exposed to 100 μg of HHA or GNA/ml for 3 days. Then, 0.25 μCi of [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine was added and, after 20 h of incubation at 37°C, the cells were precipitated in the presence of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and the precipitate was washed twice with 10% TCA, twice with 5% TCA, and once with 70% ethanol. The precipitate, containing [3H]DNA, was then examined for radioactivity in a liquid scintillation counter.

(iii) Antimetabolic activities of lectins.

To measure the inhibitory activity of GNA and HHA on macromolecular (DNA, RNA, and protein) synthesis, CEM cell cultures were seeded in 96-well microtiter plates at 105 cells/well (200 μl) in the presence of a variety of lectin concentrations (2,000, 400, 80, 16, and 3.2 μg/ml) and either 0.25 μCi of [methyl-3H]deoxythymidine (specific radioactivity, 89 Ci/mmol) or 1 μCi of [5-3H]uridine (specific radioactivity, 26 Ci/mmol) or 1 μCi of [4,5-3H]leucine (specific radioactivity, 161 Ci/mmol). After approximately 20 to 24 h, the cell cultures were treated with 10% TCA and further processed for scintillation counting of the precipitates as described above.

(iv) Animal toxicity.

Four 20- to 25-g NMRI mice were injected intravenously with 200 μl of 100 mg of GNA or 50 mg of HHA/ml in PBS in the tail as a bolus injection. The animals were then examined for acute toxicity (i.e., animal death) or visible toxic side effects for at least 5 days postinjection.

(v) Agglutinating activity of lectins.

Freshly obtained murine, rabbit, and human blood was collected in heparinized tubes and subsequently suspended in PBS at 0.5%. Then, 100 μl was added to 96-well round-bottom microtiter plates and mixed with a serial dilution of GNA and HHA in PBS (100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, and 1.56 μg/ml). The microtiter plates were then incubated at 37°C. After 4 and 24 h, the hemagglutination of the red blood cells was recorded.

Preparation of the HEC-based HHA gel.

Next, 2 g of 2-hydroxyethylcellulose type 250 HHX-Pharm (HEC; Hercules) was mixed with 5 g of glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, Bornem, Belgium), 180 mg of methylparaben (Sigma-Aldrich), and 20 mg of Propylparaben (Sigmal-Aldrich) in a mortar. Then, 20 g of demineralized water and 50 mg of lactic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and mixed to obtain a viscous gel. The gel was further diluted with demineralized water to 80 g and was then stored for 24 h under reduced pressure to remove dissolved air. NaOH (1 M; Sigma-Fluka, Bornem, Belgium) was added to adjust the pH to 4.5. Finally, the weight of the gel was adjusted to 100 g with demineralized water. The density of this blank gel was 1.06 g/ml.

Next, 2 g of this blank gel was mixed with 240 mg of HHA in a mortar to obtain a viscous and homogeneous gel. This concentrated gel was further diluted with blank gel to 8 g, yielding a final concentration of 3% HHA.

RESULTS

Antiviral activity of plant lectins.

The plant lectins GNA and HHA were examined for their potential to inhibit a variety of RNA viruses in cell culture. None of the compounds tested at a concentration as high as 400 μg/ml proved to be inhibitory to any RNA virus, including VSV in HEL cell cultures; VSV, coxsackievirus B4, and respiratory syncytial virus in HeLa cell cultures; and parainfluenza type 3 virus, reovirus type 1, Sindbis virus, coxsackievirus B4 and Punta Toro virus in Vero cell cultures. However, the plant lectins were markedly inhibitory to lentiviruses, including HIV-1 and HIV-2 in CEM cell cultures, SIV in MT-4 cell cultures, and FIV in CRFK cell cultures (Table 1). The antiviral activity ranked between 0.12 and 1.2 μg/ml for GNA and between 0.18 and 0.70 μg/ml for HHA, depending on the nature of the laboratory virus strain. GNA and HHA were also markedly inhibitory to HIV-1 (strain Ba-L)-infected primary monocyte/macrophage cell cultures (Table 1). A panel of other anti-HIV drugs that were previously reported as potential candidates for use as microbicides were included for comparative reasons. The antiviral activity of the plant lectins was comparable with that of the well-known fusion inhibitor AMD3100 (EC50 = 0.09 to 1.8 μg/ml) but was ∼10-fold higher than for tenofovir (EC50 = 2.5 to 11 μg/ml). As reported previously, the nonnucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI) UC-781 was highly active against the HIV-1 strains but inactive against HIV-2 strains (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Inhibitory activity of test compounds against the replication of several wild-type lentivirus strains and drug-resistant HIV-1(IIIB) strains in cell culture

| Virus strain | Mean EC50 (μg/ml) ± SDa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNA | HHA | AMD-3100 | UC-781 | Tenofovir | |

| HIV-1 | |||||

| IIIB | 0.33 ± 0.15 | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0.002 ± 0.0004 | 1.0 ± 0.11 |

| MN | 0.35 ± 0.21 | 0.70 ± 0.14 | 0.10 ± 0.0 | 0.005 ± 0.002 | 3.2 ± 0.20 |

| RF | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 0.70 ± 0.14 | 0.50 ± 0.14 | 0.003 ± 0.0 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

| Ba-Lb | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 1.9 | |||

| HIV-2 | |||||

| ROD | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.18 ± 0.11 | 0.77 ± 0.56 | >20 | 1.3 ± 1.3 |

| EHO | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | >20 | 0.72 ± 0.0 |

| SIVmac251c | 2.7 ± 0.77 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | >100 | >20 | 0.36 ± 0.11 |

| FIVd Petaluma | 0.09 ± 0.0 | 0.16 ± 0.0 | >20 | 2.3 | |

| NNRTI-resistant HIV-1(IIIB) | |||||

| Lys103Asn (RT) | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.60 ± 0.18 | 0.23 ± 0.10 | 15 ± 7.1 |

| Tyr181Cys (RT) | 0.85 ± 0.49 | 0.75 ± 0.35 | 0.16 ± 0.0 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 4.3 ± 2.5 |

| Lamivudine-resistant HIV-1(IIIB) Met184Val (RT) | 0.40 ± 0.14 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.16 ± 0.0 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 2.8 ± 1.8 |

| Zidovudine-resistante HIV-1(IIIB) Asp67Asn + Lys70Arg + Thr215Phe + Lys219Gln (RT) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.80 ± 0.0 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.013 ± 0.004 | 20 ± 0.0 |

| PI-resistantf HIV-1(IIIB) Val82Ala (PR) | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.53 ± 0.23 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.013 ± 0.006 | 6.7 ± 1.2 |

That is, the compound concentration required to inhibit HIV-induced cytopathicity in CEM cell cultures by 50%. Data are means of at least two to four independent experiments.

Tests were performed in primary cultures of monocyte/macrophages.

Tests were performed in MT-4 cell cultures. Similar data were obtained when the test compounds were evaluated against SIV in CEM/X174 cell cultures.

Tests were performed in CRFK cell cultures.

HIV-1 (RTMC strain).

HIV-1 strain IIIB (also containing the Met184Ile mutation in RT).

The antiviral activity of GNA and HHA was measured against a variety of clinical isolates with tropism for X4 (two isolates) and R5 (three isolates) and dual tropism for X4/R5 (five isolates) in PBMC. The coreceptor usage of the viruses (CCR5, CXCR4, or both) was determined in U87.CD4.CCR5 and U87.CD4.CXCR4 cells. Their antiviral activities ranked between 0.18 and 0.73 μg/ml for GNA and between 0.30 and 0.43 μg/ml for HHA (X4 strains), between 2.5 and 4.4 μg/ml for GNA and between 1.3 and 2.8 μg/ml for HHA (R5 strains), and between 0.51 and 7.9 μg/ml for GNA and between 0.21 and 8.9 μg/ml for HHA (X4/R5 strains), respectively. Thus, the antiviral activity of both lectins ranged from 0.18 to 8.9 μg/ml. However, the antiviral activity of GNA and HHA was usually comparable for each individual virus isolate. The average EC50s of GNA and HHA for the clinical HIV-1 isolates were 3.1 and 2.4 μg/ml, respectively. Based on these data, there seemed to be no preference of the lectins for inhibiting either X4, R5, or R5/X4 virus strains.

The plant lectins and the other microbicide candidate compounds were then evaluated for their potential to suppress HIV-1 strains that were selected for resistance to a number of anti-HIV drugs, i.e., nucleoside RT inhibitor (NRTI)-, NNRTI-, and protease inhibitor (PI)-resistant viruses, and also virus strains resistant to known adsorption and fusion inhibitors (Table 1). Both GNA and HHA inhibited all drug-resistant virus strains bearing mutations in the RT or protease gene within the same order of magnitude as the wild-type virus (Table 1). More importantly, they also efficiently prevented infection by virus strains that were resistant to the virus adsorption inhibitor DS-5000 and the virus entry inhibitors AMD3100 and SDF-1 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Inhibitory effects of plant lectins against wild-type (NL4.3) and binding/fusion-inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 strains in MT-4 cell cultures

| Virus strain | Mean EC50a (μg/ml) ± SD

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNA | HHA | AMD3100 | DS-5000b | |

| Wild-type NL4.3 | 0.57 ± 0.15 | 0.22 ± 0.14 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.14 |

| AMD3100-resistant NL4.3 | 0.59 ± 0.19 | 0.24 ± 0.14 | >1.0 | |

| SDF-1-resistant NL4.3 | 0.60 ± 0.0 | 0.55 ± 0.22 | 0.023 ± 0.003 | |

| Dextran sulfate-5000-resistant NL4.3 | 0.13 ± 0.08 | 0.23 ± 0.12 | 0.011 ± 0.006 | >125 |

That is, the compound concentration required to inhibit virus-induced cytopathicity by 50% in MT-4 cell cultures. Data are means for two independent experiments.

Data were obtained from Esté et al. (18).

Inhibitory activity of plant lectins against syncytium formation between persistently HIV-infected and uninfected lymphocytic cells.

The plant lectins, as well as the thiocarboxanilide NNRTI UC-781, the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100, and the adsorption inhibitor DS-5000, were evaluated for their inhibitory activity against syncytium (giant cell) formation between persistently HIV-1- and HIV-2-infected HUT-78 lymphocytic cells and uninfected Sup-T1 or Molt4/C8 lymphocytic cells (Table 3). Both GNA and HHA prevented giant cell formation between HUT-78/HIV-1 and Sup-T1 cells with a 50% inhibitory concentration of 1.2 μg/ml, which is only five- to sixfold higher than the EC50 for inhibition of infection by cell-free virus. AMD3100 and DS-5000 were slightly less inhibitory to syncytium formation (EC50 = 2.7 to 3.7 μg/ml). Syncytium formation in cocultures of HUT-78/HIV-2 and Sup-T1 cells was less efficiently inhibited by all compounds investigated than was found for HUT-78/HIV-1-Sup-T1 cocultures. However, when HUT-78/HIV-2 cells were cocultured with Molt4/C8 cells instead of Sup-T1 cells, most compounds were more inhibitory. HHA was most inhibitory to giant cell formation (HUT-78/HIV-2 plus Molt4/C8) at an EC50 of 2.3 μg/ml (Table 3). GNA and also AMD3100 were approximately five- to sevenfold less efficient (EC50 = 15 and 11 μg/ml, respectively), whereas DS-5000 was not effective at 100 μg/ml. As expected, the NNRTI UC-781 was not inhibitory in any of the cocultures at 10 μg/ml, i.e., at a drug concentration that is 3 orders of magnitude higher than that required to inhibit virus replication in cell cultures infected by cell-free virus (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Inhibitory effects of lectins on giant cell formation upon cocultivation of HUT-78/HIV-1 or HUT-78/HIV-2 cells with Sup-T1 or Molt4/C8 cells

| Lectin | Mean EC50a (μg/ml) ± SD

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HUT-78/HIV-1 + Sup-T1 | HUT-78/HIV-2 + Sup-T1 | HUT-78/HIV-2 + Molt4/C8 | |

| GNA | 1.25 ± 0.35 | 80 ± 28 | 15 ± 7.0 |

| HHA | 1.25 ± 0.35 | 9.0 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 0.28 |

| UC-781 | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| AMD3100 | 3.7 ± 1.7 | ≥100 | 11 ± 3.5 |

| DS-5000 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 10 ± 2.8 | >100 |

That is, the compound concentration required to prevent syncytium formation between persistently HIV-infected cells and uninfected cells by 50% within the first 24 h of cocultivation. The number of syncytia was determined under a microscope. Data are the means of two independent experiments.

Virucidal properties of plant lectins.

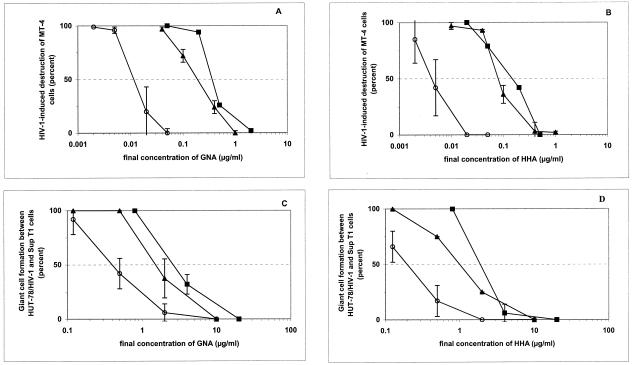

In a first set of experiments, both GNA and HHA were exposed for 2 h to cell-free HIV-1(IIIB) at ca. 200-, 80-, 20-, and 8-fold their EC50 (i.e., 50, 20, 5, and 2 μg/ml); the drug-exposed virus preparation was then diluted 1,000-fold before being added to MT-4 cell cultures. Interestingly, the virus preparations that were exposed to 50 and 20 μg of lectin/ml (followed by a 1,000-fold dilution prior to infection) were efficiently prevented (HHA) from replication in the MT-4 cell cultures or afforded 80% protection of the MT-4 cell cultures (GNA) (Fig. 1A and B). Preexposure of the virus preparations to 5 μg of lectin/ml before dilution to 0.005 μg/ml afforded 60% protection (HHA) of the MT-4 cell cultures. The lowest drug concentration (preincubation of the virus at 2 μg/ml; final concentration of lectins in the HIV-1-infected cell cultures at 0.002 μg/ml) had only ∼20% (HHA) or virtually no (GNA) protective effect (Fig. 1A and B). Thus, preexposure of the lectins to free HIV-1 particles increased the antiviral effect of the lectins by >20-fold. Tenofovir and lamivudine, under comparable experimental conditions, were unable to exert any virucidal activity against HIV (data not shown). In contrast, preexposure of the MT-4 cells, instead of the virus, to the lectins revealed no statistically significantly increased protection of the lectins against the virus-induced cytopathicity in pretreated MT-4 cells versus the HIV-1-infected cell cultures that were not preincubated with the lectins (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG. 1.

Effect of preexposure of GNA and HHA to cell-free HIV-1(IIIB) particles, uninfected MT-4 cells, Sup-T1 cells, or persistently HIV-1-infected HUT-78/HIV-1(IIIB) cells on the antiviral activity of the plant lectins. The data are the mean of two independent experiments. (A and B) Preexposure of GNA (A) or HHA (B) to cell-free virus (○) or noninfected MT-4 cells (▴) prior to virus infection of MT-4 cell cultures. As a control, the antiviral activities of the plant lectins that were not preexposed to HIV-1(IIIB) or MT-4 cells are also shown (▪). (C and D) Preexposure of GNA (C) or HHA (D) to HUT-78/HIV-1(IIIB) (○) or uninfected Sup-T1 (▴) cells prior to cocultivation of these cells with the non-drug-preexposed counterpart cells. As a control, the inhibitory effect of the plant lectins on giant cell formation between non-drug-preexposed HUT-78/HIV-1(IIIB) and Sup-T1 cells (▪) is also shown.

In a second set of experiments, either HUT-78/HIV-1 or Sup-T1 cell cultures were preexposed to high concentrations of the lectins for 2 h, after which the cell suspensions were diluted to obtain drug concentrations that were below the EC50 value of the lectins for inhibition of syncytium formation in the cocultures of HUT-78/HIV-1 and Sup-T1 cells. Drug-preexposed HUT-78/HIV-1 cells were markedly better protected against syncytium formation when mixed with nonexposed Sup-T1 cells than when drug-preexposed Sup-T1 cells were mixed with nonexposed HUT-78/HIV-1 cells (Fig. 1C and D). Comparable data were obtained for both HHA and GNA lectins. In fact, the antiviral efficiency of HHA and GNA was increased by ca. 8- to 10-fold when a short preexposure (i.e., 2 h) of the HUT-78/HIV-1 cells to the lectins was allowed.

Combination of the plant lectins with other anti-HIV drugs.

A variety of different concentrations of GNA and HHA were combined with three to five different concentrations of other anti-HIV-1 drugs in a single experiment, including the virus adsorption inhibitor DS-5000 (1 to 0.25 μg/ml), the entry and fusion inhibitors AMD3100 (0.1 to 0.006 μg/ml) and T-20 (0.1 to 0.012 μg/ml), the HIV-1-specific RT inhibitor UC-781 (0.001 to 0.00025 μg/ml), the NRTIs lamivudine (0.02 to 0.0025 μg/ml) and tenofovir (1.3 to 0.16 μg/ml), and the PI amprenavir (0.01 to 0.0012 μg/ml). Whereas the EC50s for GNA and HHA were 0.24 ± 0.08 and 0.20 ± 0.04 μg/ml, respectively, when tested as single drugs, the EC50 values for GNA and HHA ranged between 0.08 and 0.40 μg/ml and between 0.05 and 0.31 μg/ml, respectively, when combined with a variety of compound concentrations of the above-mentioned drugs. Thus, in none of the combinations with the two lectins, any significant antagonistic activity was noted when they were combined with a drug that was directed against another target in the replication cycle of the virus.

Exposure of HIV-1-infected CEM cell cultures and cocultures of persistently HIV-1-infected CEM cells and uninfected Sup-T1 cells to gel-containing HHA.

It is important to determine whether a drug that is appropriately formulated in a gel can also easily be released from the gel preparation in order to be taken up by the target (virus-infected and uninfected) cells. Therefore, a gel containing 3% HHA was suspended in cell culture medium to reach a final equivalent HHA concentration of 100 μg/ml. Then, fivefold dilutions of the HHA gel-containing medium was exposed to HIV-1-infected CEM cells or to a mixture of persistently HIV-1-infected CEM/HIV-1 and uninfected Sup-T1 cells. The gel preparation efficiently prevented syncytium formation between persistently infected and uninfected cells. Indeed, whereas HHA prevented syncytium formation at 0.8 ± 0.0 μg/ml, their corresponding gel preparations were inhibitory at 0.6 ± 0.0 μg/ml, respectively. The gel preparation also markedly inhibited cytopathicity in HIV-1-infected CEM cell cultures. Indeed, whereas HHA inhibited HIV-1- and HIV-2-induced cytopathicity at 0.30 ± 0.10 and 0.18 ± 0.11 μg/ml, the HHA gel preparations did so at 0.10 and 0.25 μg/ml. Thus, in both assays, HHA-containing gel preparations were equally effective at preventing virus infection as the free (unformulated) HHA did. These data obtained in two experiments suggest an efficient release of the plant lectins from the gel preparation.

Clearance of HIV-1 in CEM cell cultures by plant lectins.

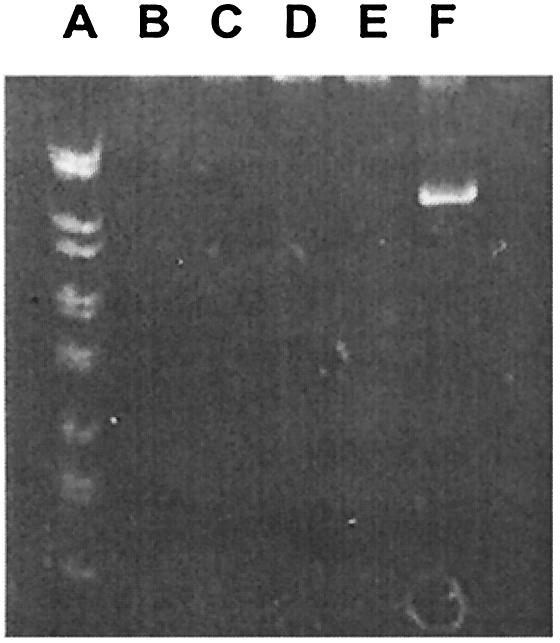

We wanted to determine whether prolonged exposure of a fixed concentration of the drug to virus-infected cells is able to clear the virus from the drug-exposed cell cultures without having given it the opportunity to escape the drug pressure and to integrate into the host cell genome. Therefore, HIV-1-infected cells were exposed to a variety of fixed concentrations of the plant lectin HHA (e.g., 25, 6.25, 1.25, or 0.5 μg/ml). Cell cultures were then passaged every 3 to 4 days (twice a week) in the presence of the same (fixed) plant lectin concentrations for at least 10 subsequent subcultivations. It was found that HHA had fully prevented virus transmission at concentrations of 25, 6.25, and 1.25 μg/ml when cell culture supernatant was transferred for each passage (i.e., at a concentration only fivefold higher than the EC50) (Fig. 2, lanes C, D, and E). When cell suspensions were transferred for each passage in the presence of fixed concentrations of the plant lectins, 25 μg of HHA/ml had cleared the virus from the cell culture (Fig. 2, lane B). Under both assay conditions, virus could not be recovered anymore from the cytopathic effect-negative cell cultures when further passaged in the absence of drug. They also proved to be p24 negative, and no proviral DNA could be detected (Fig. 2). Thus, plant lectin concentrations that were only 5- to 10-fold higher than their EC50 values were sufficient to fully suppress virus spread in the cell cultures. Although this property may seem of less importance for microbicidal drugs, it may become an important property of the drugs when they are used systemically.

FIG. 2.

PCR analysis of the presence of HIV-1(IIIB) DNA (RT gene) in HIV-1(IIIB)-infected CEM cell cultures that were exposed to fixed concentrations of HHA. Lanes: A, molecular weight markers; B, HHA at 25 μg/ml (subcultivation with cell suspensions); C, HHA at 25 μg/ml (subcultivation with cell culture supernatants); D, HHA at 6.25 μg/ml (subcultivation with cell culture supernatants); E, HHA at 1.25 μg/ml(subcultivation with cell culture supernatants); F, HHA at 0.50 μg/ml (subcultivation with cell culture supernatants).

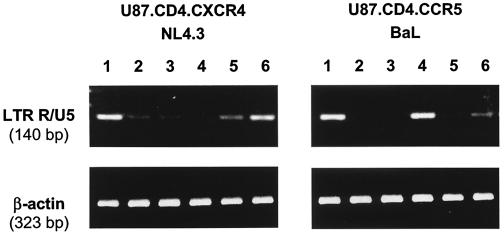

Inhibitory effect of plant lectins on the appearance of viral DNA in X4- and R5-transfected cells infected by X4 HIV-1 NL4.3 and R5 HIV-1 Ba-L.

To ascertain that the lectins act at a stage of the virus replication cycle before the very first synthesis of DNA from RNA, a semiquantitative HIV-1 LTR R/U5-specific PCR on total DNA was performed at 2 h after infection of U87.CD4.CXCR4 and U87.CD4.CCR5 cells with HIV-1/NL4.3 and HIV-1/Ba-L, respectively, in the presence of lectin concentrations that represent ∼100-fold their EC50 values. As proper controls, the CXCR4-specific inhibitor AMD3100, the adsorption inhibitor pentosan polysulfate and the CCR5-specific inhibitor TAK-779 were included. As shown in Fig. 3, GNA and HHA very efficiently inhibited replication of both X4 and R5 HIV-1 strains. In contrast, AMD3100 prevented the appearance of viral DNA in U87.CD4.CXCR4 but not in U87.CD4.CCR5 cells, whereas TAK-779 virtually completely prevented viral DNA synthesis in U87.CD4.CCR5 but not in U87.CD4.CXCR4 cells. Akin to the lectins, pentosan polysulfate inhibited both viruses. These data convincingly show that the lectins inhibit both X4 and R5 HIV-1 strains (as is also evident from the data in Table 1) and act at a step of the virus replication before the synthesis of the very first viral DNA transcripts by the RT (i.e., virus entry and/or fusion).

FIG. 3.

PCR analysis of the appearance of HIV-1 LTR R/U5 DNA in HIV-1/NL4.3-infected U87.CD4.CXCR4 and HIV-1/Ba-L-infected U87.CD4.CCR5 cell cultures. β-Actin DNA was coamplified as an internal control. Lanes: 1, virus control; 2, HHA at 20 μg/ml; 3, GNA at 20 μg/ml; 4, AMD3100 at 1 μg/ml; 5, pentosan polysulfate at 20 μg/ml; 6, TAK-779 at 1 μg/ml.

Lack of interference of plant lectins with binding of MAbs to CD4, CXCR4, CCR5, and DC-SIGN, with cytokine-triggered Ca2+ flux and with binding to uninfected T lymphocytes.

The inhibitory potential of HHA and GNA for the binding of a variety of MAbs that interact with different epitopes on CXCR4 (i.e., the MAb clones 12G5, 44717.111, and 2B11) and on CD4 (i.e., the MAb clones SK3, L120, OKT4, OKT4A) was investigated. As shown in Fig. 3 (also data not shown), the plant lectins did not inhibit binding of any of the MAbs to their target receptor molecules at concentrations that exceeded by >2 orders of magnitude those required to inhibit virus replication in the MT4 cells. This observation is in sharp contrast with AMD3100 that strongly inhibited 12G5 MAb binding to CXCR4 (Fig. 3). Also, binding of an MAb targeted at DC-SIGN, a dendritic-cell-specific receptor that can also bind HIV particles to purified monocytes was not prevented by the plant lectins (data not shown). The plant lectins were also examined for potential interference with HIV coreceptors by measuring SDF-1- and RANTES-induced calcium flux. At a concentration of 20 μg/ml, GNA and HHA were not able to inhibit SDF-1- and RANTES-induced intracellular calcium flux in SUPT1 and U87.CD4.CCR5 cells, demonstrating no interaction with the coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5.

Binding studies with FITC-conjugated GNA were also performed to reveal whether specific binding of FITC-GNA to human T lymphocytes occurred. We found that the presence of FITC on the GNA molecule did not markedly affect the anti-HIV activity of GNA in CEM cell cultures (EC50 of FITC-GNA = ∼0.8 μg/ml [versus 0.33 μg/ml for GNA]). However, no specific binding to the membrane of MT-4, HUT-78, and Sup-T1 cells was noticed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

In contrast to the adsorption inhibitor pentosan polysulfate, a marked interaction of an anti-gp120 antibody (NEA-9284) with gp120 present at the cell surface of HIV-1-persistently infected HUT78/HIV-1 cells could only occur at a lectin concentration as high as 100 μg/ml (data not shown), i.e., at a drug concentration that exceeds at least 2 orders of magnitude the antivirally effective concentration. The plant lectins were also examined for potential interference with HIV coreceptors by measuring SDF-1- and RANTES-induced flux calcium.

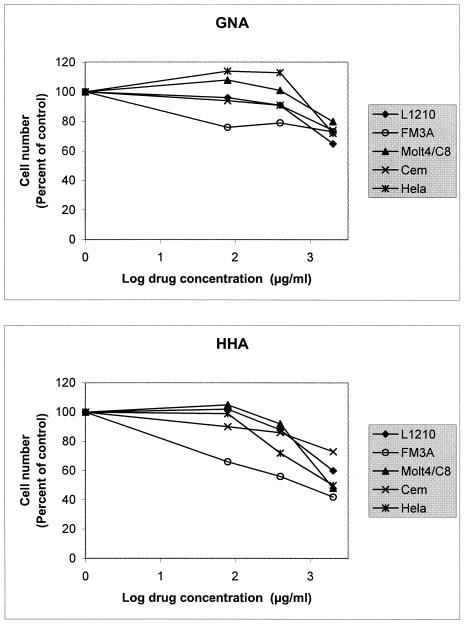

Toxicity and antimetabolic activity of plant lectins. (i) Inhibitory effect of plant lectins on the proliferation of murine and human tumor cell lines.

The cytostatic activity of GNA and HHA was examined against murine leukemia L1210, mammary carcinoma FM3A, and human lymphocytic Molt4/C8 and CEM and epithelial cervix carcinoma HeLa cells. GNA was not markedly inhibitory to cell proliferation at a concentration as high as 2,000 μg/ml (percent inhibition of cell growth in the presence of 2,000 μg of GNA/ml [relative to control] = 28% for L1210, 31% for FM3A, 31% for CEM, 23% for Molt4/C8, and 0% for HeLa). HHA inhibited FM3A cell growth at a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 302 ± 139 μg/ml but had a poor cytostatic activity against the human cells (IC50 = ≥2,000 [CEM] and 1,123 ± 394 [Molt4/C8] μg/ml), including epithelial cervix carcinoma HeLa cells (IC50 = 1,235 ± 479 μg/ml) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Inhibitory activity of GNA and HHA on cell proliferation.

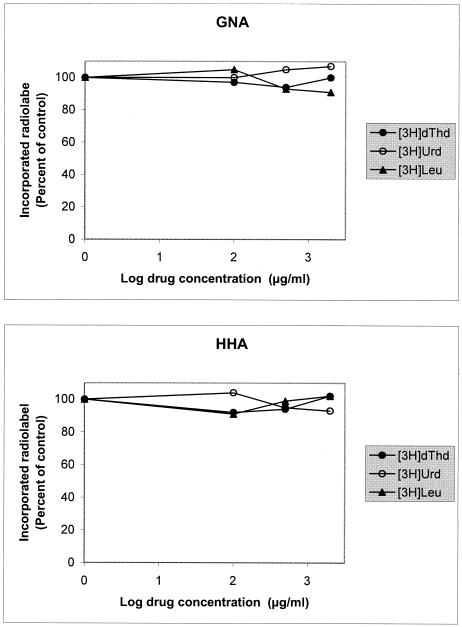

(ii) Effect of plant lectins on macromolecular synthesis in CEM cells and mitogenic stimulation of PBMC.

The lectins were investigated for their inhibitory activity against the incorporation of [3H]deoxythymidine in DNA, [3H]uridine in RNA, and [3H]leucine in proteins of CEM cells. At concentrations as high as 2,000 μg/ml, macromolecular synthesis was not affected during a 24-h exposure time of the CEM cell cultures to the plant lectins. When incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine (435,000 disintegrations per minute [dpm]), uridine (339,883 dpm), and leucine (48,899 dpm) into DNA, RNA, and protein, respectively, was examined, 100, 500, and 2,000 μg of GNA/ml incorporated these macromolecular precursors at 97, 94, and 100% of control in DNA, 100, 105, and 107% of control in RNA, and 105, 93, and 91% of control in protein, respectively. HHA did so at 92, 94, and 102% of control in DNA, at 104, 95, and 93% of control in RNA, and at 91, 99, and 102% of control in protein, respectively (Fig. 5). Also, importantly, neither GNA nor HHA had any measurable mitogenic activity in primary human PBMC cultures, since neither GNA nor HHA at 100 μg/ml stimulated [3H]deoxythymidine incorporation in DNA. In contrast, exposure of the PBMC to PHA markedly increased the incorporation of [3H]deoxythymidine into DNA (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Inhibitory activity of GNA and HHA on the incorporation of [3H]deoxythymidine, [3H]uridine, or [3H]leucine into DNA, RNA, or proteins, respectively.

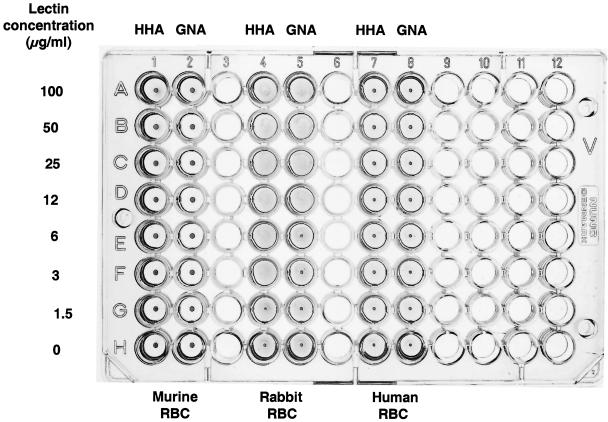

(iii) Effect of plant lectins on agglutination of mammalian blood cells.

Since many lectins show agglutinating activity on red blood cells (44), GNA and HHA were evaluated for their potential to agglutinate red blood cells of mammalian origin. Whereas rabbit erythrocytes were agglutinated at GNA and HHA concentrations as low as 12 and 3 μg/ml, respectively, the lectins did not agglutinate human and murine (mice) erythrocytes at the highest concentration tested (100 μg/ml), i.e., at a concentration that is ∼500-fold higher than the antivirally effective concentration (EC50) of the lectins in CEM cell cultures (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Hemagglutination of mammalian red blood cells by different concentrations of GNA and HHA. The data reflect a typical experiment.

(iv) Acute toxicity of plant lectins in mice.

When 20-g NMRI mice were treated intravenously with GNA at 100 mg/kg or HHA at 50 mg/kg as a bolus injection, none of the animals showed measurable toxic side effects.

Stability of plant lectins to higher temperatures or at low pH.

The plant lectins were brought into solution in PBS (pH 7.2) and kept for 3, 9, or 17 days at 50°C. HHA and GNA were then added to HIV-1-infected CEM cells, and their antiviral activities were compared to those derived for HHA and GNA that were kept in PBS for 3, 9, or 17 days at 4°C. No difference in antiviral activity was noted under these experimental conditions. The EC50 values of GNA after being exposed to 50°C for 3, 9, or 17 days were 0.7, 0.6, and 0.4 μg/ml, respectively. The EC50 values for HHA after being exposed to 50°C for 3, 9, or 17 days were 0.25, 0.25, and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively. The plant lectins were also been brought into solution in a sodium phosphate buffer at pH 5.0 for 3, 9, or 17 days prior to antiviral testing. Again, no significant decrease of antiviral potency against HIV-1 in CEM cell cultures was observed (EC50 = 0.6, 1.0, and 0.4 μg/ml [GNA] and EC50 = 0.4, 0.6, and 0.25 μg/ml [HHA]). These data suggest that both lectins were stable and fully kept their antiviral potential upon prolonged exposure to a relatively a high temperature and a low-pH environment.

DISCUSSION

Whereas HHA has a specificity for both internal and terminal α-1,3- or α-1,6-linked mannosyl units, GNA virtually exclusively targets terminal α-1,3-mannose residues (42, 44). HHA and GNA occur as peptide tetramers (50 kDa) composed of four 12.5-kDa subunits. They are not glycosylated and naturally occur as a mixture of isomers. The crystal structure of both proteins has been resolved (22, 47), and the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences for different isolectins are available from the GenBench/EMBL data library (accession numbers M88124 to M88133 and M55555 to M55558, respectively). The mannose-specific lectins GNA and HHA have a variety of properties that make them ideal candidates as potential microbicides with activity against HIV. In addition to the fact that they are odorless, colorless, and tasteless, they retain full antiviral activity after being exposed to high temperatures (i.e., several days at 50°C) and a low-pH environment (i.e., several days at pH 5.0). Interestingly, both HHA and GNA agglutinate rabbit but not murine or human erythrocytes and were not toxic when given intravenously as a bolus injection to mice at 50 to 100 mg/kg, respectively. They are nonmitogenic to human PBMC (as also reported in reference 44) and, when exposed to human lymphocytic cells at concentrations that are substantially higher than their antivirally active concentrations, no inhibitory effect on DNA, RNA, or protein synthesis was observed.

The lectins described here efficiently prevent the appearance of viral DNA in virus-exposed cell cultures. In fact, these lectins proved to be potent and highly selective inhibitors of the spread of HIV by virus-to-cell, as well as cell-to-(virus-infected) cell contact. Indeed, they not only efficiently prevent infection of human T-lymphocytic cells by cell-free virus particles but also markedly prevent syncytium formation between persistently HIV-infected cells and uninfected T lymphocytes. This property is important in view of the predominant transmission of HIV through sexual intercourse by virus-infected cells rather than by free virus particles. Moreover, we showed for the first time that short exposure of cell-free HIV-1 particles or persistently HIV-1-infected HUT-78 cells, but not of uninfected cells, to HHA and GNA resulted in a marked potentiation and long-lasting antiviral activity of the lectins, an interesting property for a drug that should be applied intravaginally as a microbicide against HIV. Also, the lectins proved to be able to clear the virus from the drug-exposed cell cultures upon prolonged administration to the cells, a property that is also beneficial for potential microbicide drugs.

It is well known that there is an increasing incidence of transmission of mutant virus strains that are resistant to the variety of drugs currently used for HIV treatment. Interestingly, the lectins invariably kept their inhibitory potential against virus strains containing mutations characteristic for NNRTIs (i.e., nevirapine and efavirenz), NRTIs (i.e., zidovudine and lamivudine), and PIs (i.e., amprenavir) (34) and, more importantly, they also kept their full inhibitory activity against mutant virus strains that became resistant to the adsorption inhibitor DS-5000, the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100, or the natural chemokine ligand of CXCR4, SDF-1 (13, 17, 18, 28, 37, 38). These findings not only suggest that the lectins are able to suppress any HIV strain that is involved in virus transmission but also that the lectins must act at a different molecular (micro)target in the HIV entry (adsorption/fusion) process than the other known entry inhibitors of HIV. In fact, since FIV does not use CD4 as a receptor for entry (16, 46), the exquisite activity of HHA and GNA against FIV (Table 1) suggests that lectin interaction with CD4 is not required to explain their antiviral potential. These observations are in agreement with our cytofluorimetric findings that the lectins do not interfere with MAb binding to CD4, CXCR4, and DC-SIGN or with SDF-1- and RANTES-induced signaling. Also, we show that FITC-labeled GNA did not demonstrate specific binding to the HUT-78, MT-4, and Sup-T1 cell membranes. This may point to a specific interaction of the lectins with molecules that are present on the virus envelope. The molecular target of HHA and GNA can be a virus-specific component (i.e., gp120 and gp41) or a component present either on the virus envelope or on the cell membrane that is different from the well-known CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 receptors and interacts with a viral component such as gp120 or gp41. Interaction of the lectins with binding of an MAb recognizing an epitope in the V3 loop of gp120 was only observed at a drug concentration that exceeded the antivirally active concentration by at least 2 orders of magnitude. However, Saifuddin et al. (33) recently demonstrated that mannose-binding lectins bind to the carbohydrate structure on gp120/gp41 of a variety of primary HIV isolates, since soluble mannose was able to block the interaction. Astoul et al. (1) have demonstrated a direct interaction of the high-mannose glycans of glycoprotein gp120 of HIV-1 with mannose-binding lectins. Also, it was found by Biacore technology (M. Schreiber and M. Vossman, Hamburg, Germany) that HHA and GNA specifically interacted with gp120 (data not shown). In fact, we recently selected for plant lectin (e.g., HHA and GNA)-resistant HIV-1 strains and found consistent changes in a number of amino acids in gp120 but not in gp41. Moreover, the majority of mutations that appeared in the gp120 of plant lectin-resistant viruses were at N glycosylation sites (J. Balzarini, K. Van Laethem, S. Hatse, K. Vermeire, E. De Clercq, W. Peumans, E. Van Damme, A.-M. Vandamme, and D. Schols, Abstr. First Int. Meet. Glycovirol., no. 029, p. 62, 2003). These observations point again to gp120, in particular to the sugar part of gp120, as a molecular target for the plant lectins used in the present study and are in agreement with our other findings presented here. Since many plant lectins are known to contain several sugar-binding sites at the same molecule, tight interaction of the plant lectins to several glycosylation sites on the heavily glycosylated gp120 (containing ca. 24 glycosylated asparagines [25, 26]) can be expected and may explain the enhanced antiviral activity of the plant lectins upon preincubation. Further investigations are under way to pinpoint the exact molecular mechanism of antiviral action of the mannose-specific plant lectins.

Our data on HIV-1-infected CEM and persistently HIV-1-infected CEM/HIV-1 cocultures with Sup-T1 cells exposed to HHA-containing gel preparations are of particular interest. Indeed, the HHA-containing gel preparation was as antivirally active as free HHA in both assays. The remarkable protection demonstrated by the HHA gel formulation is indicative of a rapid release of active HHA from the gel vehicle into the hydrophilic cell culture medium. Since not much more than 1 ml of gel per intravaginal administration is recommended in humans, 30 mg of HHA present in 1 ml of a 3% HHA- containing gel can readily be exposed to the vaginal-cervical environment, reflecting a drug concentration that is at least 5 orders of magnitude higher than the EC50 of HHA in cell culture.

It is worth noting that resistance development of HIV-1 against HHA and GNA is far more difficult to obtain in cell culture under experimental conditions in which NRTIs (such as lamivudine) or NNRTIs (such as UC-781) easily selected for drug-resistant mutant virus strains. In fact, attempts to select for significant HHA-resistant HIV-1 in CEM cell cultures have failed thus far within a time frame of at least 30 subcultivations (data not shown).

It seems now to be imperative to investigate the microbicidal properties of the mannose-specific plant lectins in a relevant animal model. Recently, Di Fabio et al. (14) reported on the vaginal transmission of HIV-1 in hu-SCID mice as a new model for the evaluation of vaginal microbicides. This model turned out to be particularly useful to test the activity of compounds against cell-associated HIV, and therefore, should be highly relevant for the evaluation of compounds such as the lectins. In this respect it is of particular importance to notice that the lectins do not agglutinate murine red blood cells and do not show acute toxicity to mice when administered intravenously at a high-drug-concentration bolus injection. For the latter experiments, 100 mg of GNA and 50 mg of HHA/kg were the highest drug doses that could be injected into mice under experimental conditions at which the compounds could be intravenously injected as a solution. However, these drug concentrations—if the total blood volume of mice is estimated to be ∼2.5 ml—reflect final lectin concentrations of ∼0.8 and 0.4 mg/ml, of plasma, respectively. This is an ∼1,000-fold higher lectin concentration than the EC50 value in cell culture. These findings argue for the safety of the lectins if a fraction of these substances administered intravaginally or rectally reach the bloodstream. Also, given the similar antiretroviral activities of the plant lectins against SIV, FIV, and HIV (Table 1), monkeys intravaginally or rectally infected with SHIV or SIV or cats naturally or experimentally infected with FIV may turn out to be very useful animal models for exploring the microbicidal activity of plant lectins. In fact, Veazey et al. recently showed partial prevention of virus (SHIV) transmission to macaque monkeys by a vaginally applied MAb to HIV-1 gp120 (45). Also, cyanovirin, a mannose-specific lectin derived from a blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) has proven to be able to prevent virus infection in SIV-exposed monkeys (39). These findings support the concept that viral entry inhibitors (of protein nature) can be helpful for preventing the sexual transmission of HIV-1 to humans. These observations support similar studies of the plant lectins as potential microbicides in such animal models.

In conclusion, the mannose-specific plant lectins, subject of the present study, are endowed with a number of favorable and interesting properties that make them primary candidate drugs to be considered for further (pre)clinical investigations as potential microbicides.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the European Commission (René Descartes Prize-2001 project no. HPAW-CT-2002-90001), the Vth Framework Programme (project no. QLRT-2000-00291), the VIth Framework Programme project EMPRO (no. 503558), the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-Vlaanderen (G.0267.04), and a grant from the ANRS. S.H. is a recipient of a postdoctoral FWO (Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-Vlaanderen) fellowship, and K.V. is a fellow of the “Onderzoeksfonds Leuven.”

We thank Ann Absillis, Sandra Claes, Eric Fonteyn, Ria Van Berwaer, Nancy Schuurman, and Lizette van Berckelaer for excellent technical assistance and Christiane Callebaut for dedicated editorial help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Astoul, C. H., J. W. Peumans, and E. J. Van Damme. 2000. Rough: accessibility of the high-mannose glycans of glycoprotein gp120 from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 probed by in vitro interaction with mannose-binding lectins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 274:455-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, M., O. Nishimura, N. Kanzaki, M. Okamoto, H. Sawada, Y. Iizawa, M. Shiraishi, Y. Aramaki, K. Okonogi, Y. Ogawa, K. Meguro, and M. Fujino. 1999. A small-molecule, nonpeptide CCR5 antagonist with highly potent and selective anti-HIV-1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5698-5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzarini, J., L. Naesens, J. Slachmuylders, H. Niphuis, I. Rosenberg, A. Hol, H. Schellekens, and E. De Clercq. 1991. 9-(2-Phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA) effectively inhibits retrovirus replication in vitro and simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. AIDS 5:21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balzarini, J., D. Schols, J. Neyts, E. Van Damme, W. Peumans, and E. De Clercq. 1991. α-(1-3)- and α-(1-6)-d-mannose-specific plant lectins are markedly inhibitory to human immunodeficiency virus and cytomegalovirus infections in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:410-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balzarini, J., J. Neyts, D. Schols, M. Hosoya, E. Van Damme, W. Peumans, and E. De Clercq. 1992. The mannose-specific plant lectins from Cymbidium hybrid and Epipactis helleborine and the (N-acetylglucosamine)n-specific plant lectin from Urtica dioica are potent and selective inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus and cytomegalovirus replication in vitro. Antivir. Res. 18:191-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balzarini, J., A. Karlsson, M.-J. Pérez-Pérez, M.-J. Camarasa, and E. De Clercq. 1993. Knocking-out concentrations of HIV-1-specific inhibitors completely suppress HIV-1 infection and prevent the emergence of drug-resistant virus. Virology 196:576-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd, M. R., K. R. Gustafson, J. B. McMahon, R. H. Shoemaker, B. R. O'Keefe, T. Mori, R. J. Gulakowski, L. Wu, M. I. Rivera, C. M. Laurencot, M. J. Currents, J. H. Cardellina, Jr., R. W. Buckheit, Jr., P. L. Nara, L. K. Pannell, R. C. Sowder, Jr., and L. E. Henderson. 1997. Discovery of cyanovirin-N, a novel human immunodeficiency virus-inactivating protein that bindings viral surface envelope glycoprotein gp120: potential applications to microbicide development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1521-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocchi, F., A. L. DeVico, A. Garzino-Demo, S. K. Arya, R. C. Gallo, and P. Lusso. 1995. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science 270:1811-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniel, M. D., N. I. Letvin, N. W. King, M. Kannagi, P. K. Sehgal, R. D. Hunt, P. J. Kanki, M. Essex, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1985. Isolation of a T-cell tropic HTLV III-like retrovirus from macaques. Science 228:1201-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Clercq, E. 2002. Strategies in the design of antiviral drugs. Nat. Rev. 1:13-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Clercq, E., J. Descamps, G. Verhelst, R. T. Walker, A. S. Jones, P. F. Torrence, and D. Shugar. 1980. Comparative efficacy of antiherpes drugs against different strains of herpes simplex virus. J. Infect. Dis. 141:563-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng, H., R. Liu, W. Ellmeier, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, P. Di Marzio, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. M. Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major coreceptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Vreese, K., V. Kofler-Mongold, C. Leutgeb, V. Weber, K. Vermeire, S. Schacht, J. Anné, E. De Clercq, R. Datema, and G. Werner. 1996. The molecular target of bicyclams, potent inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 70:689-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Fabio, S., G. Giannini, C. Lapenta, M. Spada, A. Binelli, E. Germinario, P. Sestili, F. Belardelli, E. Proietti, and S. Vella. 2001. Vaginal transmission of HIV-1 in hu-SCID mice: a new model for the evaluation of vaginal microbicides. AIDS 15:2231-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egberink, H., M. Borst, H. Niphuis, J. Balzarini, H. Neu, H. Schellekens, E. De Clercq, M. Horzinek, and M. Koolen. 1990. Suppression of feline immunodeficiency virus infection in vivo by 9-(2-phosphonomethoxyethyl)adenine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:3087-3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egberink, H. F., E. De Clercq, A. L. W. Van Vliet, J. Balzarini, G. J. Bridger, G. Henson, M. C. Horzinek, and D. Schols. 1999. Bicyclams, selective antagonists of the human chemokine receptor CXCR4, potently inhibit feline immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 73:6346-6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esté, J. A. 2001. HIV resistance to entry inhibitors. AIDS Rev. 3:121-132. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esté, J. A., D. Schols, K. De Vreese, K. Van Laethem, A.-M. Vandamme, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1997. Development of resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to dextran sulfate associated with the emergence of specific mutations in the envelope gp120 glycoprotein. Mol. Pharmacol. 52:98-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammar, L., S. Eriksson, and B. Morein. 1989. Human immunodeficiency virus glycoproteins: lectin binding properties. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 5:495-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen, J.-E. S., C. M. Nielsen, C. Nielsen, P. Heegaard, L. R. Mathiesen, and J. O. Nielsen. 1989. Correlation between carbohydrate structures on the envelope glycoprotein gp120 of HIV-1 and HIV-2 and syncytium inhibition with lectins. AIDS 3:635-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatse, S., K. Princen, L.-O. Gerlach, G. Bridger, G. Henson, E. De Clercq, T. W. Schwartz, and D. Schols. 2001. Mutation of Asp171 and Asp262 of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 impairs its coreceptor function for human immunodeficiency virus-1 entry and abrogates the antagonistic activity of AMD3100. Mol. Pharmacol. 60:164-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hester, G., H. Kaku, I. J. Goldstein, and C. S. Wright. 1995. Structure of mannose-specific snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) lectin is representative of a new plant lectin family. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaku, H., E. J. M. Van Damme, W. J. Peumans, and I. J. Goldstein. 1990. Carbohydrate-binding specificity of the daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus) and amaryllis (Hippeastrum hybr.) bulb lectins. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 279:298-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilby, J. M., S. Hopkins, T. M. Venetta, B. DiMassimo, G. A. Cloud, J. Y. Lee, L. Alldredge, E. Hunter, D. Lambert, D. Bolognesi, T. Matthews, M. R. Johnson, M. A. Nowak, G. M. Shaw, and M. S. Saag. 1998. Potent suppression of HIV-1 replication in humans by T-20, a peptide inhibitor of gp41-mediated virus entry. Nat. Med. 4:1302-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwong, P. D., R. Wyatt, J. Robinson, R. W. Sweet, J. Sodroski, and W. A. Hendrickson. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonard, C. K., M. W. Spellman, L. Riddle, R. J. Harris, J. N. Thomas, and T. J. Gregory. 1990. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 265:10373-10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lifson, J., S. Coutreé, E. Huang, and E. Engleman. 1986. Role of envelope glycoprotein carbohydrate in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infectivity and virus-induced cell fusion. J. Exp. Med. 164:2101-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin, P. F., H. Samanta, C. M. Bechtold, C. A. Deminie, A. K. Patick, M. Alam, K. Riccardi, R. E. Rose, R. J. White, and R. J. Colonno. 1996. Characterization of siamycin I, a human immunodeficiency virus fusion inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:133-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsui, T., S. Kobayashi, O. Yoshida, S.-I. Ishii, Y. Abe, and N. Yamamoto. 1990. Effects of succinylated concanavalin A on infectivity and syncytial formation of human immunodeficiency virus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 179:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matthews, T. J., K. J. Weinhold, H. K. Lyerly, A. J. Langlois, H. Wigzell, and D. P. Bolognesi. 1987. Interaction between the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type IIIB envelope glycoprotein gp120 and the surface antigen CD4: role of carbohydrate in binding and cell fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:5424-5428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mori, T., and M. R. Boyd. 2001. Cyanovirin-N, a potent human immunodeficiency virus-inactivating protein, blocks both CD4-dependent and CD4-independent binding of soluble gp120 (sgp120) to target cells, inhibits sCD4-induced binding of sgp120 to cell-associated CXCR4, and dissociates bound sgp120 from target cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:664-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Müller, W. E. G., K. Renneisen, M. H. Kreuter, H. C. Schröder, and I. Winkler. 1988. The d-mannose-specific lectin from Gerardia savaglia blocks binding of human immunodeficiency virus type I to H9 cells and human lymphocytes in vitro. J. Acquir. Immun. Defic. Syndr. 1:453-458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saifuddin, M., M. L. Hart, H. Gewurz, Y. Zhang, and G. T. Spear. 2000. Interaction of mannose-binding lectin with primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Gen. Virol. 81:949-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schinazi, R. F., B. A. Larder, and J. W. Mellors. 2000. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance: 2000-2001 update. Int. Antiviral News. 8:65-91. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schols, D., R. Pauwels, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1990. Dextran sulfate and other polyanionic anti-HIV compounds specifically interact with the viral gp120 glycoprotein expressed by T cells persistently infected with HIV-1. Virology 175:556-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schols, D., S. Struyf, J. Van Damme, J. A. Esté, G. Henson, and E. De Clercq. 1997. Inhibition of T-tropic HIV strains by selective antagonization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J. Exp. Med. 186:1383-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schols, D., J. A. Esté, C. Cabrerar, and E. De Clercq. 1998. T-cell-line-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that is made resistant to stromal cell-derived factor 1α contains mutations in the envelope gp120 but does not show a switch in coreceptor use. J. Virol. 72:4032-4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torre, V. S., A. J. Marozsan, J. L. Albright, K. R. Collins, O. Hartley, R. E. Offord, M. E. Quinones-Mateu, and E. J. Arts. 2000. Variable sensitivity of CCR5-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates to inhibition by RANTES analogs. J. Virol. 74:4868-4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai, C.-C., P. Emau, Y. Jiang, M. B. Agy, R. J. Shattock, A. Schmidt, W. R. Morton, K. R. Gustafson, and M. R. Boyd. 2004. Cyanovirin-N inhibits AIDS virus infections in vaginal transmission models. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 20:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vahlenkamp, T. W., A. De Ronde, J. Balzarini, L. Naesens, E. De Clercq, M. J. T. van Eijk, M. C. Horzinek, and H. F. Egberink. 1995. (R)-9-(2- Phosphonylmethoxypropyl)-2,6-diaminopurine is a potent inhibitor of feline immunodeficiency virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:746-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Damme, E. J. M., A. K. Allen, and W. J. Peumans. 1987. Isolation and characterization of a lectin with exclusive specificity toward mannose from snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) bulbs. FEBS Lett. 215:140-144. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Damme, E. J. M., I. J. Goldstein, and W. J. Peumans. 1991. A comparative study of mannose-binding lectins from the Amaryllidaceae and Alliaceae. Phytochemistry 30:509-514. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Damme, E. J. M., A. K. Allen, and W. J. Peumans. 1998. Related mannose-specific lectins from different species of the family Amaryllidaceae. Plant Physiol. 73:52-57. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Damme, E. J. M., W. J. Peumans, A. Pusztai, and S. Bardocz (ed.) 1998. Handbook of plant lectins: properties and biomedical applications. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, N.Y.

- 45.Veazey, R. S., R. J. Shattock, M. Pope, J. C. Kirijan, J. Jones, Q. Hu, T. Ketas, P. A. Marx, P. J. Klasse, D. R. Burton, and J. P. Moore. 2003. Prevention of virus transmission to macaque monkeys by a vaginally applied monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 gp120. Nat. Med. 9:343-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willett, B. J., M. J. Hosie, O. Jarrett, and J. C. Neil. 1994. Identification of a putative cellular receptor for feline immunodeficiency virus as the feline homologue of CD9. Immunology 81:228-233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wood, S. D., L. M. Wright, C. D. Reynolds, P. J. Rizkallah, A. K. Allen, W. J. Peumans, and E. J. M. Van Damme. 1999. Structure of the native (unligated) mannose-specific bulb lectin from Scilla campanulata (bluebell) at 1.7 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D 55:1264-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]