Abstract

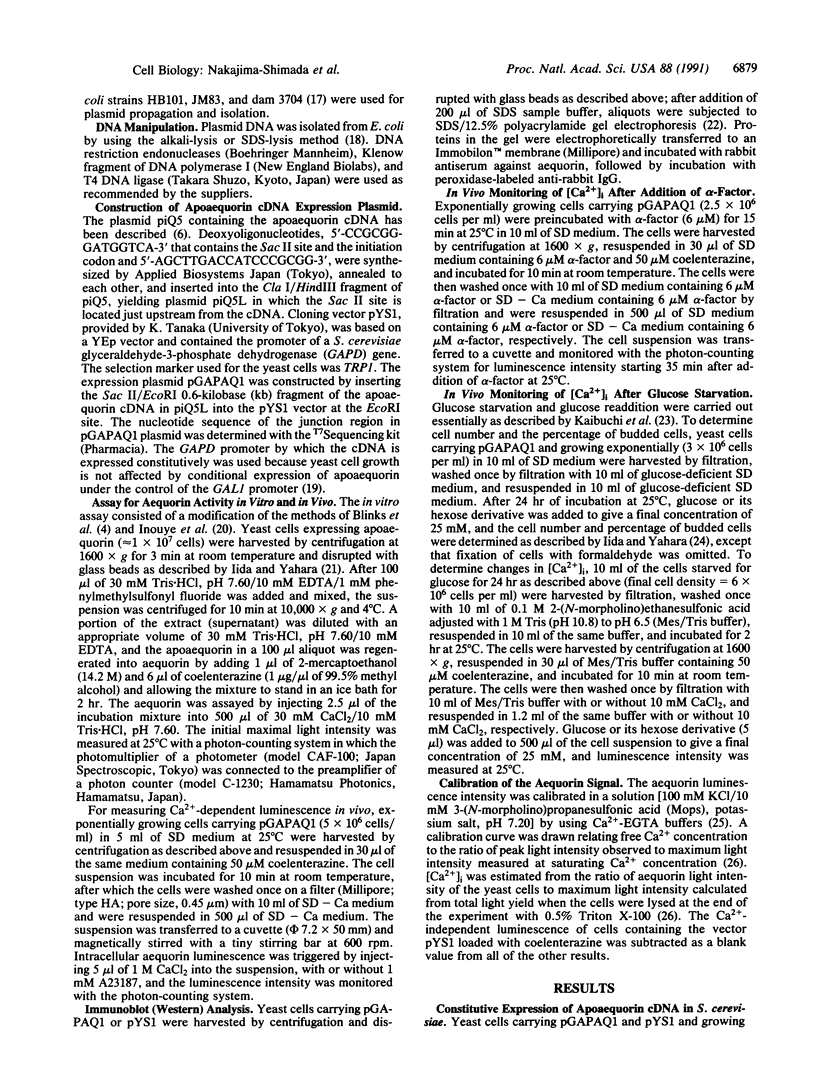

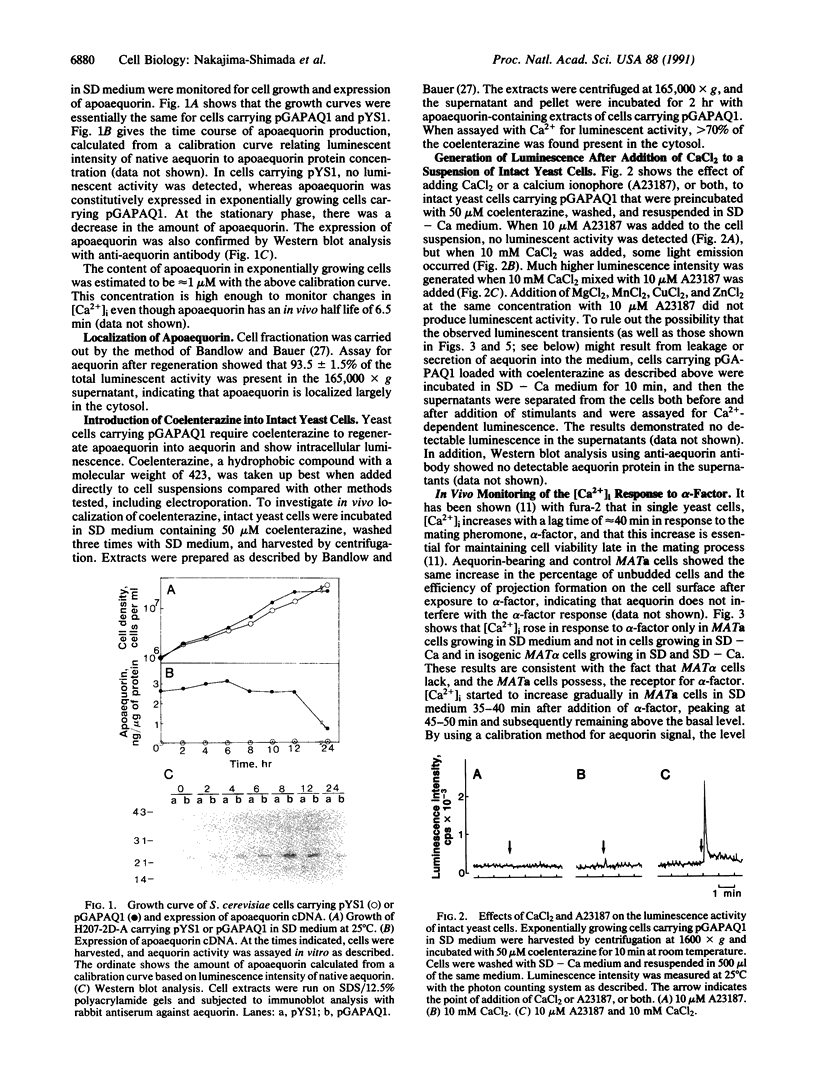

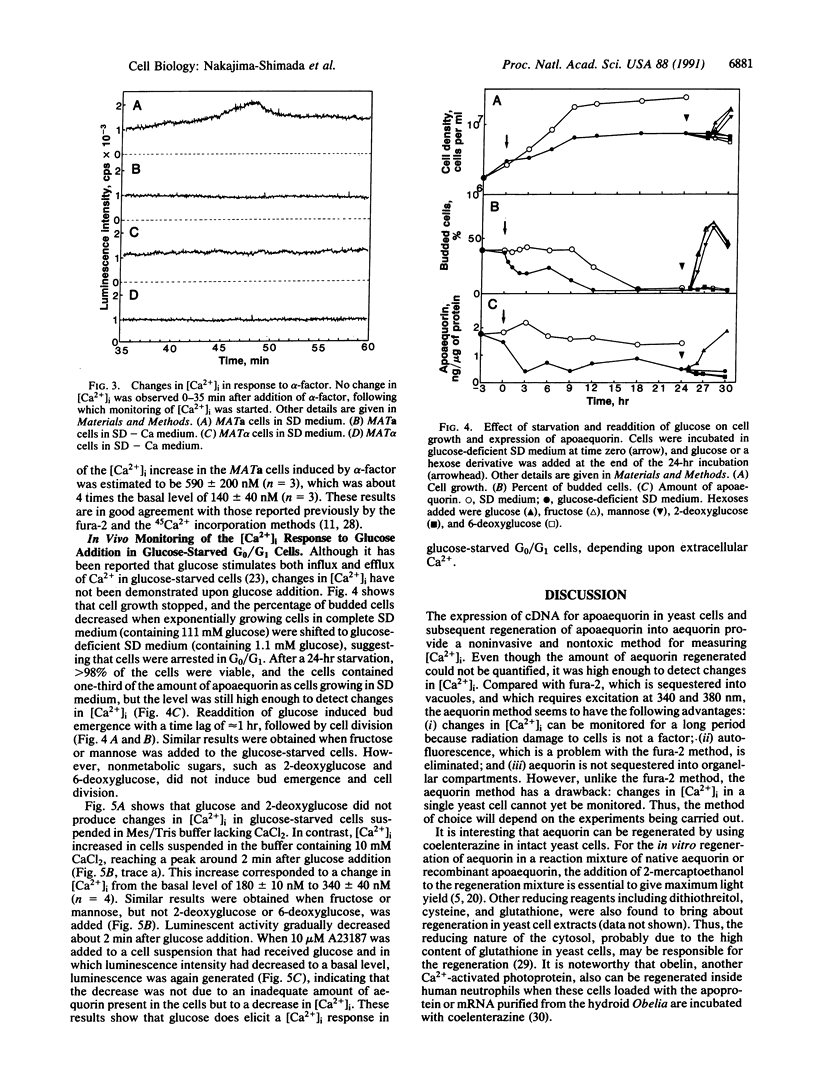

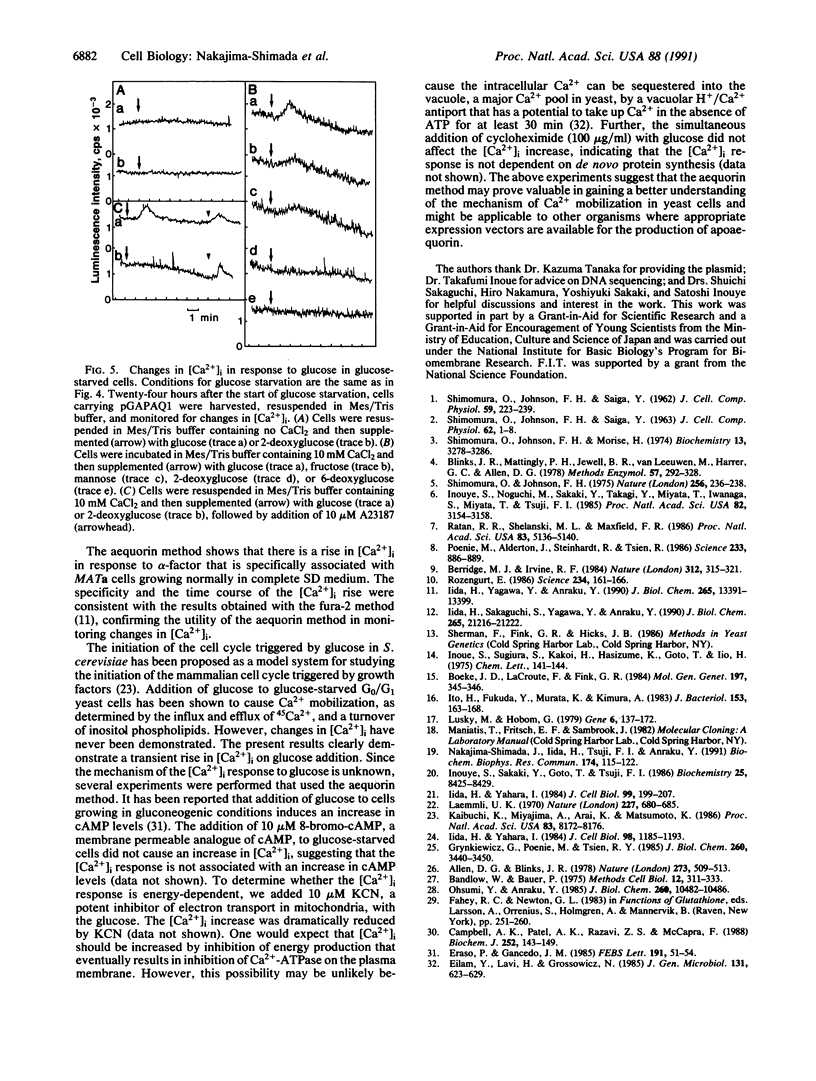

A method is described for measuring cytosolic free Ca2+ and its time-dependent changes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by using the luminescent protein aequorin as a Ca(2+)-specific indicator. This method with intact yeast cells is labeled "in vivo" to distinguish it from methods with cell extracts, labeled "in vitro." A plasmid in which the apoaequorin cDNA was joined downstream from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene promoter was constructed and introduced into yeast cells. The intracellular concentration of apoaequorin expressed by the cDNA was approximately 1 microM, which was high enough to detect the cytosolic Ca2+. Growth of the transformed cells was normal. In the in vitro method, apoaequorin in crude cell extracts was regenerated into aequorin by mixing with coelenterazine, the substrate for the luminescence reaction, whereas in the in vivo method, aequorin was regenerated by incubating intact cells with coelenterazine. Simultaneous addition of 10 mM CaCl2 and 10 microM A23187, a Ca2+ ionophore, to coelenterazine-incorporated cells generated luminescence. Coelenterazine-incorporated cells also responded to native extracellular stimuli. A mating pheromone, alpha-factor, added to cells of mating type a or alpha, generated extracellular Ca(2+)-dependent luminescence specifically in a mating type cells, with maximal intensity occurring 45-50 min after addition of alpha-factor. Glucose added to glucose-starved G0/G1 cells stimulated an increase in extracellular Ca(2+)-dependent luminescence with maximal intensity occurring 2 min after addition. These results show the usefulness of the aequorin system in monitoring [Ca2+]i response to extracellular stimuli in yeast cells.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen D. G., Blinks J. R. Calcium transients in aequorin-injected frog cardiac muscle. Nature. 1978 Jun 15;273(5663):509–513. doi: 10.1038/273509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandlow W., Bauer P. Separation and some properties of the inner and outer membranes of yeast mitochondria. Methods Cell Biol. 1975;12:311–333. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60962-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J., Irvine R. F. Inositol trisphosphate, a novel second messenger in cellular signal transduction. Nature. 1984 Nov 22;312(5992):315–321. doi: 10.1038/312315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke J. D., LaCroute F., Fink G. R. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5'-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197(2):345–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00330984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. K., Patel A. K., Razavi Z. S., McCapra F. Formation of the Ca2+-activated photoprotein obelin from apo-obelin and mRNA inside human neutrophils. Biochem J. 1988 May 15;252(1):143–149. doi: 10.1042/bj2520143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985 Mar 25;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida H., Sakaguchi S., Yagawa Y., Anraku Y. Cell cycle control by Ca2+ in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990 Dec 5;265(34):21216–21222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida H., Yagawa Y., Anraku Y. Essential role for induced Ca2+ influx followed by [Ca2+]i rise in maintaining viability of yeast cells late in the mating pheromone response pathway. A study of [Ca2+]i in single Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells with imaging of fura-2. J Biol Chem. 1990 Aug 5;265(22):13391–13399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida H., Yahara I. Durable synthesis of high molecular weight heat shock proteins in G0 cells of the yeast and other eucaryotes. J Cell Biol. 1984 Jul;99(1 Pt 1):199–207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida H., Yahara I. Specific early-G1 blocks accompanied with stringent response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae lead to growth arrest in resting state similar to the G0 of higher eucaryotes. J Cell Biol. 1984 Apr;98(4):1185–1193. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye S., Noguchi M., Sakaki Y., Takagi Y., Miyata T., Iwanaga S., Miyata T., Tsuji F. I. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for the luminescent protein aequorin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 May;82(10):3154–3158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983 Jan;153(1):163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaibuchi K., Miyajima A., Arai K., Matsumoto K. Possible involvement of RAS-encoded proteins in glucose-induced inositolphospholipid turnover in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Nov;83(21):8172–8176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusky M., Hobom G. Inceptor and origin of DNA replication in lambdoid coliphages. I. The lambda DNA minimal replication system. Gene. 1979 Jun;6(2):137–172. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima-Shimada J., Iida H., Tsuji F. I., Anraku Y. Galactose-dependent expression of the recombinant Ca2(+)-binding photoprotein aequorin in yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991 Jan 15;174(1):115–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90493-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi Y., Anraku Y. Specific induction of Ca2+ transport activity in MATa cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by a mating pheromone, alpha factor. J Biol Chem. 1985 Sep 5;260(19):10482–10486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poenie M., Alderton J., Steinhardt R., Tsien R. Calcium rises abruptly and briefly throughout the cell at the onset of anaphase. Science. 1986 Aug 22;233(4766):886–889. doi: 10.1126/science.3755550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratan R. R., Shelanski M. L., Maxfield F. R. Transition from metaphase to anaphase is accompanied by local changes in cytoplasmic free calcium in Pt K2 kidney epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jul;83(14):5136–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt E. Early signals in the mitogenic response. Science. 1986 Oct 10;234(4773):161–166. doi: 10.1126/science.3018928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIMOMURA O., JOHNSON F. H., SAIGA Y. Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1962 Jun;59:223–239. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030590302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura O., Johnson F. H., Morise H. Mechanism of the luminescent intramolecular reaction of aequorin. Biochemistry. 1974 Jul 30;13(16):3278–3286. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura O., Johnson F. H. Regeneration of the photoprotein aequorin. Nature. 1975 Jul 17;256(5514):236–238. doi: 10.1038/256236a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]