Abstract

Three fluoroquinolone-susceptible and five fluoroquinolone-resistant (two with ParC Ser79Phe mutations, one with a GyrA Ser81Phe mutation, and two that were efflux positive) Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates were exposed to one, two, four, eight, and sixteen times the MICs of ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin. Mutational frequencies were calculated at each multiple of the MIC for which growth was observed. Mutant prevention concentrations (MPCs) and the multiple of the MIC at the MPC (MPMIC) were evaluated. All resulting mutants were sequenced for quinolone resistance-determining region changes in GyrA and ParC and were evaluated for reserpine-sensitive efflux. The MPC order was generally ciprofloxacin > levofloxacin > gatifloxacin > moxifloxacin > gemifloxacin. The MPMIC order varied depending on the genetic constitution of the original isolates from which the mutants were generated. For those mutants created from fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates (those that had wild-type ParC and GyrA and were efflux negative), the MPMIC order was ciprofloxacin = moxifloxacin > gemifloxacin > levofloxacin > gatifloxacin. The MPMICs of each fluoroquinolone for mutants created from isolates with a ParC mutation (with wild-type GyrA and efflux negative) were similar. A similar occurrence was observed with the mutants created from the efflux-positive isolates (with wild-type ParC and GyrA). The MPMIC order for the mutants created from the isolate with a GyrA mutation (with wild-type ParC and efflux negative) was ciprofloxacin = gemifloxacin > levofloxacin = moxifloxacin > gatifloxacin. Gatifloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin may be intrinsically more able to prevent the development of resistance by fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates, isolates that are efflux positive, or isolates that carry a GyrA mutation. However, once a ParC mutation is present, the MPC increases dramatically for all fluoroquinolones.

The primary goals of antibiotic treatment of respiratory tract infections are clinical efficacy of treatment, pathogen eradication, and prevention of resistance development. Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the most significant causes of community-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, otitis media, sinusitis, and acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, and it is responsible for substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide (1, 4, 19, 22). Due to the increasing prevalence of resistance to the antibiotics traditionally used in the treatment of respiratory infections, β-lactams and macrolides, the newer fluoroquinolones have been recommended for treatment of multiple drug-resistant S. pneumoniae (2, 3, 6, 24). The respiratory fluoroquinolones, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin, show enhanced activities against gram-positive organisms like S. pneumoniae, including multiple drug-resistant S. pneumoniae, in addition to their improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties compared to older agents, such as ciprofloxacin (4, 6, 15, 24).

Fluoroquinolones inhibit DNA synthesis by binding to enzyme-DNA complexes involving either DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV (2, 6, 7, 11-14, 17). This binding results in the formation of ternary complexes that inhibit the progression of the replication fork (6, 11, 12, 14). The bactericidal activity of fluoroquinolones results from the release of a double-stranded break following stabilization of the ternary complex (6, 7, 11, 12, 14). DNA gyrase, an A2B2 tetramer encoded by gyrA and gyrB, removes superhelical twists ahead of the replication fork and adds negative supercoils into DNA to combat the overwinding resulting from replication (7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 24). Topoisomerase IV is a C2E2 tetramer, encoded by parC and parE, that decatenates sister chromatids during the segregation of replicated chromosomes (7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 24).

Resistance to fluoroquinolones in S. pneumoniae is mediated by at least three mechanisms: chromosomal mutations in DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV and active efflux (6, 15). Resistance results primarily from spontaneous point mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of gyrA (DNA gyrase) and/or parC (topoisomerase IV) (6, 11, 22, 24). An efflux pump, PmrA, in S. pneumoniae may mediate active fluoroquinolone efflux (2, 6, 20).

In order to limit the emergence of resistant strains and prevent fluoroquinolones from being rendered ineffective, tailored use of the respiratory fluoroquinolones is imperative. Implementing new dosing strategies for fluoroquinolones is one technique that may be employed to reduce resistance formation (10). This suggestion is based on the notion that there is a concentration range for every fluoroquinolone-pathogen combination that selects resistant mutants (10). The limits of this range are the concentration that inhibits the majority of susceptible growth and the concentration that inhibits organisms containing a single resistance mutation (10). The bacterial cells must acquire two or more resistance mutations in order to grow in the presence of fluoroquinolone concentrations greater than the upper limit (3, 9, 10). This antibiotic level is referred to as the mutant prevention concentration (MPC) (3, 9, 10). Dosing above the MPC has been suggested as a method by which the selection of mutants during antibiotic treatment could be minimized (9). The MPC has been experimentally defined as the drug concentration that prohibits the growth of mutants from a susceptible population of more than 1010 cells (3, 9, 21).

The purpose of this study was to systematically examine the intrinsic development of fluoroquinolone resistance in S. pneumoniae by determining the mutational frequencies of and MPCs for S. pneumoniae isolates with known genetic backgrounds exposed to ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin. Unlike other recent MPC studies of S. pneumoniae that rapidly screened hundreds of isolates with unknown genetic backgrounds (4), we chose to use a methodical, genetic approach. We carefully selected isolates that had known genetic backgrounds and genetically characterized all isolates both prior to and following the MPC study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eight previously characterized S. pneumoniae isolates were selected for single-step mutational studies (5, 23). Seven of the isolates (isolates 2587, 2663, 2670, 4610, 14744, 15017, and 16072) were collected between 1997 and 2000 as part of an ongoing national surveillance study, the Canadian Respiratory Organisms Susceptibility Study (23). The identity of each isolate was confirmed by the central reference laboratory (Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada), and the isolates were then stored in skim milk and frozen at −80°C (23). One additional isolate (1146) was requested from Brueggemann et al., as we had not received isolates with only a GyrA mutation as part of the Canadian Respiratory Organisms Susceptibility Study (5). The MICs were determined by broth microdilution, using cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood, in accordance with NCCLS recommendations (18). The final bacterial inoculum of each well of the panel was 5 × 105 CFU/ml. The MICs were recorded as the lowest antibiotic concentration required to inhibit visible growth (17). All MIC determinations were conducted at least in triplicate on separate days. The MICs of ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin for each isolate are recorded in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

MICs of ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin for all S. pneumoniae isolates used in mutational studiesa

| Isolate | Genetic constitution of isolates prior to mutational analysis

|

MIC (μg/ml)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ParC | GyrA | Efflux | CIP | GAT | GEM | LVX | MXF | |

| 2670 | wt | wt | Negative | 1 | 0.25 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| 2587 | wt | wt | Negative | 1 | 0.25 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| 2663 | wt | wt | Negative | 1 | 0.125 | 0.008 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| 4610 | Ser79Phe | wt | Negative | 4 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.25 |

| 14744 | Ser79Phe | wt | Negative | 4 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.25 |

| 1146 | wt | Ser81Phe | Negative | 8 | 4 | 0.06 | 8 | 2 |

| 15017 | wt | wt | Positive | 4 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.12 |

| 16072 | wt | wt | Positive | 4 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.12 |

wt, wild type; CIP, ciprofloxacin; GAT, gatifloxacin; GEM, gemifloxacin; LVX, levofloxacin; and MXF, moxifloxacin.

The antibiotics used in this study were obtained from their manufacturers: ciprofloxacin was from Bayer, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; gatifloxacin was from Bristol-Myers Squibb, New Brunswick, N.J.; gemifloxacin was from GlaxoSmithKline, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; levofloxacin was from Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; and moxifloxacin was from Bayer.

The isolates were grown overnight on Trypticase soy agar plates plus 5% sheep blood at 35°C in a CO2 incubator. The overnight growth was swabbed into Mueller-Hinton broth with 2% lysed horse blood and incubated for 45 min at 35°C in ambient air in order to achieve an inoculum near 1010 CFU/ml. Spontaneous single-step S. pneumoniae mutants were obtained by plating the resulting inocula on Mueller-Hinton agar plates containing 5% sheep blood and one, two, four, eight, or sixteen times the MIC of each fluoroquinolone (22). Additionally, the inocula were plated onto drug-free plates to obtain a total number of CFU per milliliter. The antibiotic-containing plates were incubated in a CO2-enriched environment at 35°C for 48 to 72 h, and the antibiotic-free plates were incubated under the same conditions for 24 h. Colony counts were conducted after the appropriate incubation period. The mutational frequencies were calculated as the ratio of colonies grown on antibiotic-containing plates to colonies formed on drug-free plates (19, 22). The MPC for each drug-isolate combination was defined as the lowest fluoroquinolone concentration that prevented growth of resistant mutants (3, 9, 21), while the mutant prevention MIC (MPMIC) was the multiple of the MIC corresponding to the MPC. All resulting mutants were stocked in skim milk and stored at −80°C for further study. The statistical significance of the difference between the MPCs and MPMICs of the evaluated fluoroquinolones was determined with Statistical Analysis and Data Analysis software (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah).

The QRDRs of gyrA and parC were sequenced prior to the onset of this study in order to genetically characterize the isolates. Genomic DNA, isolated from confluent bacterial growth on Mueller-Hinton agar plates plus 5% lysed horse blood, was used as a template for PCR. The QRDRs of gyrA and parC were amplified by PCR using primers previously described by Morrissey et al. (17). The products were purified with Microcon microconcentrators (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, Mass.) to remove any impurities. Sequencing was carried out using an ABI PRISM BigDye terminator kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) on an automated sequencer (model 310; Applied Biosystems). Sequencing was performed in the forward and reverse directions using primers described by Morrissey et al. (17). Sequences were aligned with the reference strains in order to identify any amino acid substitutions.

Additionally, the isolates were tested for reserpine-sensitive efflux. The MICs of ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin for each isolate were determined by agar dilution on Mueller-Hinton agar plates plus 5% sheep blood in the presence and absence of reserpine (10 μg/ml). Isolates demonstrating a fourfold or greater reduction in MIC in the presence of reserpine were considered positive for reserpine-sensitive efflux (2).

RESULTS

The genetic constitutions of the isolates are summarized in Table 1. Isolates 2587, 2663, and 2670 are fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates (with wild-type ParC and GyrA and efflux negative). Isolates 4610 and 14744 have a Ser79Phe mutation in ParC (with wild-type GyrA and efflux negative). Isolates 15017 and 16072 are efflux-positive isolates (with wild-type ParC and GyrA). Isolate 1146 has a Ser81Phe mutation in GyrA (with wild-type ParC and efflux negative).

Table 2 displays the MPCs of the five fluoroquinolones as both MPCs and MPMICs. We chose to evaluate the MPC in relation to the actual drug concentration and as a function of the MIC increase (n-fold; MPMIC) required to reach this level. The possibility of clinically administering the required antibiotic concentrations to limit resistant-mutant formation can be determined from the MPCs. The MPMIC permits a comparison of the antibiotics' intrinsic abilities to restrict the formation of resistant mutants. For the mutants created from the fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates (with wild-type ParC and GyrA and efflux negative), the MPC order was ciprofloxacin ≫ levofloxacin > moxifloxacin = gatifloxacin > gemifloxacin (8 to 16 ≫ 2 > 0.5 to 1 = 0.5 to 1 > 0.06 to 0.13 μg/ml). The order of MPMICs was ciprofloxacin = moxifloxacin > gemifloxacin > levofloxacin > gatifloxacin (8 to 16 = 8 to 16 > 4 to 16 > 4 > 2 to 8 times the MIC). For the mutants created from the isolates with a ParC mutation (with wild-type GyrA and efflux negative), the MPC order was ciprofloxacin > levofloxacin > gatifloxacin > moxifloxacin > gemifloxacin (64 > 32 > 8 > 4 > 0.5 to 1 μg/ml), and the MPMICs were, surprisingly, 8 to >16 times the MIC for all fluoroquinolones. The MPC order for the mutants created from the isolate with a GyrA mutation (with wild-type ParC and efflux negative) was ciprofloxacin > levofloxacin > gatifloxacin = moxifloxacin > gemifloxacin (64 > 16 > 4 = 4 > 0.5 μg/ml), and the MPMIC order was ciprofloxacin = gemifloxacin > levofloxacin = moxifloxacin > gatifloxacin (eight = eight > two = two > one times the MIC). The mutants created from the efflux-positive isolates (with wild-type ParC and GyrA) had an MPC order of ciprofloxacin > levofloxacin > gatifloxacin > moxifloxacin > gemifloxacin (16 > 4 to 8 > 2 > 0.5 to 1 > 0.25 μg/ml), and the MPMICs were two to eight times the MIC for all the fluoroquinolones. Due to the limited number of mutants, the differences between the MPCs and MPMICs of the fluoroquinolones were not significant.

TABLE 2.

MPCs obtained for single-step fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of S. pneumoniae isolatesa

| Isolate | Ciprofloxacin

|

Gatifloxacin

|

Gemifloxacin

|

Levofloxacin

|

Moxifloxacin

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPMIC | MPC (μg/ml) | MPMIC | MPC (μg/ml) | MPMIC | MPC (μg/ml) | MPMIC | MPC (μg/ml) | MPMIC | MPC (μg/ml) | |

| Wild-type GyrA and ParC, efflux negative | ||||||||||

| 2587 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.13 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 0.5 |

| 2663 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 0.13 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 0.5 |

| 2670 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.06 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 1 |

| ParC Ser79Phe, wild-type GyrA, efflux negative | ||||||||||

| 4610 | 16 | 64 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 16 | 32 | >16 | >4 |

| 14744 | 16 | 64 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 4 |

| GyrA Ser81Phe, wild-type ParC, efflux negative | ||||||||||

| 1146 | 8 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 0.5 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 4 |

| Efflux positive, wild-type GyrA and ParC | ||||||||||

| 15017 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 0.25 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

| 16072 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0.25 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 |

MPMIC are given in multiples of the MIC of each drug.

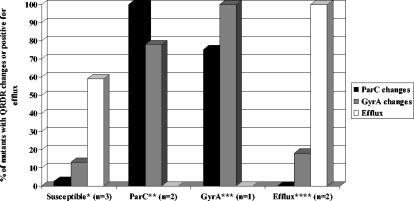

The QRDRs of ParC and GyrA were sequenced, and reserpine-sensitive efflux for each mutant was evaluated as described above. The sequencing and efflux results are summarized in Fig. 1. The mutants created from the fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates (with wild-type ParC and GyrA and efflux negative) acquired very few QRDR changes. Five of 39 (13%) mutants had mutations in GyrA (selected with moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin), and 1 of 39 (2.5%) isolates had mutations in ParC (selected with gemifloxacin). Twenty-three of 39 (59%) mutants were positive for reserpine-sensitive ciprofloxacin efflux. Thirty-one of 40 (78%) mutants created from the isolates with a ParC mutation (with wild-type GyrA and efflux negative) acquired secondary mutations in GyrA (Ser81Tyr and Glu85Lys), whereas all were reserpine-sensitive ciprofloxacin efflux negative. Six of eight (75%) mutants created from the isolate with a GyrA mutation (with wild-type ParC and efflux negative) acquired secondary mutations in ParC (Ser79Tyr), while all remained reserpine-sensitive ciprofloxacin efflux negative. All the mutants created from the efflux-positive isolates (with wild-type GyrA and ParC) remained efflux positive. Only 3 of 17 (18%) mutants acquired QRDR substitutions. These changes occurred in GyrA (Ser81Tyr) and were selected with gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin.

FIG. 1.

GyrA and ParC QRDR substitutions and efflux results present in the S. pneumoniae mutants. Susceptible (*) isolates (with wild-type ParC and GyrA and efflux negative) were 2587, 2663, and 2670. Isolates with a Ser79Phe mutation in ParC (**) (with wild-type GyrA and efflux negative) were 4610 and 14744. The isolate with a Ser81Phe GyrA mutation (***) (with wild-type ParC and efflux negative) was 1146. Efflux-positive (****) isolates (with wild-type ParC and GyrA and efflux positive) were 15017 and 16072.

DISCUSSION

Due to the time-consuming nature of genetically characterizing all isolates prior to and following the mutational analysis, only a few representative isolates could be evaluated. However, we felt it was vital to study the organism and the development of resistance in this protracted manner. In a recent study by Blondeau et al. reporting the MPCs of fluoroquinolones for clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae, wide MPC ranges were found, as many more isolates were tested and the isolates were not genetically characterized prior to MPC testing (4). Our MPC range for each category of organisms (fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates [with wild-type ParC and GyrA and efflux negative], isolates with a ParC mutation [with wild-type GyrA and efflux negative], isolates with a GyrA mutation [with wild-type ParC and efflux negative], and efflux-positive isolates [with wild-type GyrA and ParC]) is much smaller, as their genetic constitutions were known prior to study. The unsequenced clinical isolates in the Blondeau et al. study may contain parC or gyrA amino acid substitutions that could account for their high MPCs. Clinically, the rapid phenotypic MPC analysis may be sufficient, but in order to completely analyze the mechanisms of resistance development, the extended method is necessary.

This thorough mutational analysis of the respiratory fluoroquinolones has highlighted and revealed many important aspects of the future of fluoroquinolone therapy. By using the genetic approach of characterizing all isolates prior to and following the mutational study instead of a rapid method of MPC determination, we can confidently state various conclusions about the development of fluoroquinolone resistance. First, among the respiratory fluoroquinolones, gatifloxacin is the least likely to select for resistance in ciprofloxacin-susceptible S. pneumoniae isolates, followed by levofloxacin, gemifloxacin, and moxifloxacin (in that order). Second, no differences exist between the fluoroquinolones in their likelihood of selecting for mutations with efflux-positive isolates. Third, the presence of a GyrA mutation prior to MPC analysis had the greatest impact on the ciprofloxacin and gemifloxacin MPCs, although we only studied one strain. As gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin preferentially bind GyrA, we expected the largest MPC increase to be observed for those fluoroquinolones. We are currently pursuing these findings. Last, once a ParC mutation was present, as in isolates 4610 and 14744, the MPC of all fluoroquinolones increased dramatically. Almost all isolates with a ParC mutation acquired secondary mutations in GyrA and became highly resistant to all fluoroquinolones. This result is particularly important in light of recent reports by Lim et al. that 59% of isolates with levofloxacin MICs of 2 μg/ml (susceptible) carry ParC mutations (16). The repercussions of this situation have already been observed in reports of treatment failures during levofloxacin therapy (8).

Although fluoroquinolone resistance in S. pneumoniae isolates remains low, the opportunity for increased resistance exists as the use of fluoroquinolones for the treatment of respiratory tract infections rises (11, 23). The potential for resistance formation should thus be considered when specific fluoroquinolones are selected for treatment. Including MPCs as part of a dosing strategy may be one means of limiting the selection of fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants and preserving this class of antibiotic.

Acknowledgments

H.J.S. receives funding from the CIHR-ICID training program. This research was funded in part by the University of Manitoba, Abbott Laboratories Ltd., AstraZeneca Canada Inc., Aventis Pharma, Bayer Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Group, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Ortho Inc., Merck Frosst Canada & Co., Pfizer/Pharmacia Canada Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst Canada Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball, P. 1999. Therapy for pneumococcal infection at the millennium: doubts and certainties. Am. J. Med. 107(1A):77S-85S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bast, D., D. E. Low, C. L. Duncan, L. Kilburn, L. A. Mandell, R. J. Davidson, and J. C. S. de Azavedo. 2000. Fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: contributions of type II topoisomerase mutations and efflux to levels of resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3049-3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blondeau, J. M. 1999. A review of the comparative in vitro activities of 12 antimicrobial agents, with a focus on five new ‘respiratory quinolones.’ J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43(Suppl. B):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blondeau, J. M., A. Xilin, G. Hansen, and K. Drlica. 2001. Mutant prevention concentrations of fluoroquinolones for clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:433-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brueggemann, A. B., S. L. Coffman, P. Rhomberg, H. Huynh, L. Almer, A. Nilius, R. Flamm, and G. V. Doern. 2002. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae in United States since 1994-1995. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:680-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush, K., and R. Goldschmidt. 2000. Effectiveness of fluoroquinolones against gram-positive bacteria. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 1:22-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu, D. T. W., and L. L. Shen. 1995. Quinolones: synthetic antibacterial agents. In P. A. Hunter, G. K. Darby, and N. J. Russell (ed.), Fifty years of antimicrobials: past perspectives and future trends. Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 8.Davidson, R., R. Cavalcanti, J. L. Brunton, D. J. Bast, J. C. S. de Azavedo, P. Kibsey, C. Fleming, and D. E. Low. 2002. Resistance to levofloxacin and failure of treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:747-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong, Y., X. Zhao, B. N. Kreisworth, and K. Drlica. 2000. Mutant prevention concentration as a measure of antibiotic potency: studies with clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2581-2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drlica, K. 2001. A strategy for fighting antibiotic resistance. ASM News 67:27-33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heaton, V. J., J. E. Ambler, and L. M. Fisher. 2000. Potent antipneumococcal activity of gemifloxacin is associated with dual targeting of gyrase and topoisomerase IV, an in vivo target preference for gyrase, and enhanced stabilization of cleavable complexes in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3112-3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooper, D. C. 2001. Mechanisms of action of antimicrobials: focus on fluoroquinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 1):S9-S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooper, D. C. 2000. Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance, p. 685. In V. A. Fischetti (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 14.Khodursky, A. B., and N. R. Cozzarelli. 1998. The mechanisms of inhibition of topoisomerase IV by quinolone antibacterials. J. Biol. Chem. 42:27668-27677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legg, J. M., and A. J. Bint. 1999. Will pneumococci put quinolones in their place? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:425-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim, S., D. Bast, A. McGeer, J. de Azavedo, and D. E. Low. 2003. Antimicrobial susceptibility breakpoints and first-step parC mutations in Streptococcus pneumoniae: redefining fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:833-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrissey, J., and J. George. 1999. Activities of fluoroquinolones against Streptococcus pneumoniae type II topoisomerases purified as recombinant proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2579-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1998. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 8th informal supplement. M100-S8. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 19.Pan, X., J. Ambler, S. Mehtar, and L. M. Fisher. 1996. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2321-2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Putman, M., H. W. van Veen, and W. N. Konings. 2000. Molecular properties of bacterial multidrug transporters. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:672-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sindelar, G., X. Zhao, A. Liew, Y. Dong, T. Lu, J. Zhou, J. Domagala, and K. Drlica. 2000. Mutant prevention concentration as a measure of fluoroquinolone potency against mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3337-3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tankovic, J., B. Perichon, J. Duval, and P. Courvalin. 1996. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2505-2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhanel, G. G., L. Palatnick, K. A. Nichol, T. Bellyou, D. E. Low, and D. J. Hoban. 2003. Antimicrobial resistance in respiratory tract Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates: results of the Canadian Respiratory Organism Susceptibility Study, 1997 to 2002. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1867-1874. (Erratum, 47: 2716.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhanel, G. G., K. Ennis, L. Vercaigne, A. S. Gin, J. Embil, and D. J. Hoban. 2002. Critical review of fluoroquinolones: focus on respiratory infections. Drugs 62:13-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]