Abstract

This study evaluated the relationship between florfenicol resistance and flo genotypes in 1,987 Escherichia coli isolates from cattle. The flo gene was detected in 164 isolates, all of which expressed resistance to florfenicol at MICs of ≥256 μg/ml. The florfenicol MICs for all isolates that lacked flo were ≤16 μg/ml.

Florfenicol is a fluorinated analog of chloramphenicol approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1996 for the treatment of bovine respiratory disease (BRD) pathogens. The main florfenicol targets in respiratory diseases of cattle are Pasteurella multocida, Mannheimia haemolytica, and Haemophilus somnus. Florfenicol is occasionally used extra-label in the treatment of calf diarrhea (10) and can be effective against Escherichia coli strains isolated from diarrheic calves (9). Florfenicol binds to the 50S subunit of the bacterial ribosome and disrupts protein synthesis. E. coli strains have been recovered with a gene known as flo that expresses resistance to florfenicol and chloramphenicol and is typically located on large transferable plasmids (7). Neither the enzyme chloramphenicol acetyltransferase nor the nonenzymatic chloramphenicol resistance gene cmlA confers resistance to florfenicol (10).

Past studies documented florfenicol resistance in animal isolates of E. coli. White et al. (10) found that for 44 of 48 neonatal calf diarrhea E. coli isolates, there was decreased susceptibility to florfenicol, flo was present, and the florfenicol MIC range was 16 to ≥256 μg/ml. For 4 of the 48 E. coli isolates, cmlA was present, flo was not present, and the florfenicol MIC range was ≤8 to 64 μg/ml. Keyes et al. (6) analyzed chloramphenicol-resistant E. coli from sick chickens and found that some isolates possessed the flo gene. The florfenicol MICs for isolates harboring flo were ≥32 μg/ml, whereas the florfenicol MICs for isolates without flo were ≤8 μg/ml. Bischoff et al. (1) analyzed 48 chloramphenicol-resistant E. coli isolates from cases of neonatal swine diarrhea. The florfenicol MIC for one isolate, which possessed flo, was 256 μg/ml. The florfenicol MICs for the remaining 47 isolates ranged from 8 to ≥16 μg/ml.

Currently, there are no National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) MIC breakpoints approved to indicate florfenicol resistance in E. coli, and many studies (1, 10) use MIC breakpoints for the BRD pathogens. When these guidelines are used, an MIC of ≥8 μg/ml indicates resistance, an MIC of 4 μg/ml indicates intermediate susceptibility, and an MIC of ≤2 μg/ml indicates susceptibility. Previous studies demonstrated that the presence of flo is associated with very high florfenicol MICs (1, 6, 10). Therefore, we hypothesized that MIC breakpoints for BRD pathogens would not be useful in correlating the presence of flo in E. coli isolates with the observed florfenicol MIC. The objective of this study was to evaluate the relationship between florfenicol resistance phenotypes and flo genotypes in commensal bovine isolates of E. coli.

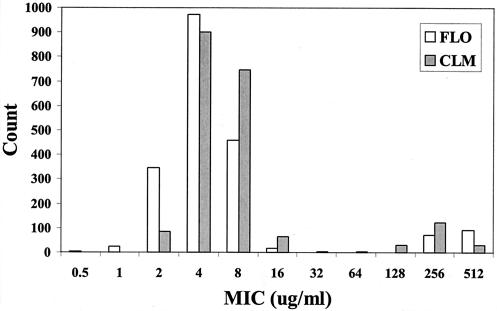

During an intensive, longitudinal study of antimicrobial resistance in dairies, 1,987 E. coli isolates were cultured from 195 bovine fecal samples. Cattle of different ages in each of four dairies were sampled every 3 months for 18 months. The antimicrobial MICs of florfenicol and chloramphenicol were determined for each isolate by use of broth microdilution in accordance with NCCLS guidelines (8). Antibiotic concentrations ranged from 0.5 to 512 μg/ml. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic completely inhibiting visible growth. E. coli ATCC 25922, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as quality control strains. The florfenicol MIC distribution showed a clear bimodal pattern (Fig. 1), with the MICs for all isolates being either ≤16 or ≥256 μg/ml. The distribution for chloramphenicol MICs had a similar pattern, although isolates were identified along the entire continuum of MICs.

FIG. 1.

Histogram depicting the distribution of florfenicol (FLO) and chloramphenicol (CLM) MICs for the 1,987 E. coli isolates tested.

We designed and optimized a multiplex PCR assay (Table 1) for the detection of the flo and cmlA genes. This assay included E. coli 16S rRNA primers as the DNA template quality control. Both the flo and cmlA genes were detected in the E. coli isolates in this study (Table 2). We did not observe any isolates that possessed the cmlA gene but lacked the flo gene. All of the isolates for which the florfenicol MICs were ≥256 μg/ml possessed the flo gene; no isolates for which the florfenicol MIC was ≤16 μg/ml possessed the flo gene (Fig. 1). The isolates that possessed the flo gene came from 60 different animals, and all four farms were represented. Some animals had flo-positive E. coli isolates on more than one sampling.

TABLE 1.

Primers and conditions used in PCR

| Gene or primer | Primer sequence | Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| flo | F: 5′-AAT CAC GGG CCA CGC TGT ATC-3′ | 215 | 2 |

| R: 5′-CGC CGT CAT TCT TCA CCT TC-3′ | |||

| cmlA | F: 5′-CCG CCA CGG TGT TGT TGT TAT C-3′ | 698 | 6 |

| R: 5′-CAC CTT GCC TGC CCA TCA TTA G-3′ | |||

| 16S rRNA | F: 5′-GGA TTA GAT ACC CTG GTA GTC C-3′ | 320 | 5 |

| R: 5′-TCG TTG CGG GAC TTA ACC CAA C-3′ | |||

| BOXA1R primer | 5′-CTA CGG CAA GGC GAC GCT GAC G-3′ | Multiple fragments | 4 |

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of flo and cmlA genes in the 1,987 E. coli isolates tested

| Chloramphenicol and/or florfenicol resistance genotype | MIC range (μg/ml)a of:

|

No. of isolates (%) positive for resistance gene | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloramphenicol | Florfenicol | ||

| flo | 128-≥512 | 256-≥512 | 149 (7.5) |

| flo, cmlA | 256-≥512 | 256-≥512 | 15 (0.76) |

Determined by microdilution methods according to NCCLS standards and guidelines (8).

All 99 flo-positive isolates from one farm were tested to determine if the flo gene resided on conjugative plasmids. Conjugation was carried out by plate mating, with a nalidixic acid-resistant E. coli strain (DH5α) as the recipient. Thirty-seven of the isolates (37.3%) were able, by conjugation, to transfer resistance to florfenicol. The remaining isolates may have the flo gene located on a chromosome or on nonconjugative plasmids (10).

All E. coli isolates were genotyped by repetitive-element PCR fingerprinting (Table 1) using the BOXA1R primer and a touchdown program similar to that described by Johnson and O'Bryan (4). For quality control, a standard lab strain was amplified in each set of reactions to demonstrate repeatability and consistency across all experiments. Dendrograms were created by use of BioNumerics 3.0 software with the Dice coefficient (3) and the neighbor-joining algorithm. Sixty-six different E. coli repetitive-element PCR fingerprint patterns were found among the flo-positive isolates. Some flo-positive fingerprint patterns persisted over several samplings. No fingerprint patterns were shared between E. coli isolates that could transfer florfenicol resistance by conjugation and those that could not. This study corroborated the findings of other studies (1, 6, 10) in which a diverse array of E. coli strains possessed a flo gene carried on conjugative plasmids in many of the isolates.

The florfenicol MICs for many chloramphenicol-resistant, flo-negative E. coli isolates would be considered as indicating resistance if the breakpoints for BRD pathogens were used. According to this classification, 476 (24.1%) flo-negative E. coli isolates from this study would be considered florfenicol resistant. Other studies had similar findings in which flo-negative E. coli isolates would be considered florfenicol resistant (1, 6, 10). Some investigators have suggested that perhaps another mechanism confers an intermediate florfenicol MIC in the range of 8 to 32 μg/ml (1, 10). Research studies or surveillance systems might overestimate florfenicol resistance if they were to use the BRD pathogen MIC breakpoints for E. coli isolates. In the case of florfenicol resistance, the resistance phenotype is often used as a surrogate for the underlying genetic mechanism conferring the resistance, which in this case is the presence of the flo gene. If the goal of the resistance classification system is to have some relationship to the likely genetic mechanisms for resistance, then florfenicol resistance in E. coli might be defined by an MIC of ≥32 μg/ml. In our work and in other studies, an MIC of ≥32 μg/ml rarely would have been confused with a chloramphenicol resistance mechanism. Clinical relevance of an MIC breakpoint of 32 μg/ml would need to be examined.

Acknowledgments

The research in this project has complied with all relevant federal animal use guidelines and institutional policies.

This project was supported by USDA National Research Initiative competitive grant 00-35212-9398 (R. S. Singer).

We thank Elizabeth Lyle and Heather Estilo for technical assistance and Richard Wallace for his involvement with the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bischoff, K. M., D. G. White, P. F. McDermott, S. Zhao, S. Gaines, J. J. Maurer, and D. J. Nisbet. 2002. Characterization of chloramphenicol resistance in beta-hemolytic Escherichia coli associated with diarrhea in neonatal swine. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:389-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolton, L. F., L. C. Kelley, M. D. Lee, P. J. Fedorka-Cray, and J. J. Maurer. 1999. Detection of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium DT104 based on a gene which confers cross-resistance to florfenicol and chloramphenicol. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1348-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dice, L. R. 1945. Measures of the amount of ecological association between species. Ecology 26:297-302. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson, J. R., and T. T. O'Bryan. 2000. Improved repetitive-element PCR fingerprinting for resolving pathogenic and nonpathogenic phylogenetic groups within Escherichia coli. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:265-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kariyama, R., R. Mitsuhata, J. W. Chow, D. B. Clewell, and H. Kumon. 2000. Simple and reliable multiplex PCR assay for surveillance isolates of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3092-3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keyes, K., C. Hudson, J. J. Maurer, S. Thayer, D. G. White, and M. D. Lee. 2000. Detection of florfenicol resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolated from sick chickens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:421-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meunier, D., S. Baucheron, E. Chaslus-Dancla, J. L. Martel, and A. Cloeckaert. 2003. Florfenicol resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Newport mediated by a plasmid related to R55 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:1007-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals. Approved standard M31-A, 2nd ed. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 9.Orden, J. A., J. A. Ruiz-Santa-Quiteria, S. Garcia, D. Cid, and R. De La Fuente. 2000. In vitro susceptibility of Escherichia coli strains isolated from diarrhoeic dairy calves to 15 antimicrobial agents. J. Vet. Med. B 47:329-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White, D. G., C. Hudson, J. J. Maurer, S. Ayers, S. Zhao, M. D. Lee, L. Bolton, T. Foley, and J. Sherwood. 2000. Characterization of chloramphenicol and florfenicol resistance in Escherichia coli associated with bovine diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4593-4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]