Abstract

Mutations in the translation elongation factor G (EF-G) make Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium resistant to the antibiotic fusidic acid. Fusr mutants are hypersensitive to oxidative stress and rapidly lose viability in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. We show that this phenotype is associated with reduced activity of two catalase enzymes, HPI (a bifunctional catalase-hydroperoxidase) and HPII (a monofunctional catalase). These catalases require the iron-binding cofactor heme for their activity. Fusr mutants have a reduced rate of transcription of hemA, a gene whose product catalyzes the first committed step in heme biosynthesis. Hypersensitivity of Fusr mutants to hydrogen peroxide is abolished by the presence of δ-aminolevulinic acid, the precursor of heme synthesis, in the growth media and by the addition of glutamate or glutamine, amino acids required for the first step in heme biosynthesis. Fluorescence measurements show that the level of heme in a Fusr mutant is significantly lower than it is in the wild type. Heme is also an essential cofactor of cytochromes in the electron transport chain of respiration. We found that the rate of respiration is reduced significantly in Fusr mutants. Sequestration of divalent iron in the growth media decreases the sensitivity of Fusr mutants to oxidative stress. Taken together, these results suggest that Fusr mutants are hypersensitive to oxidative stress because their low levels of heme reduce both catalase activity and respiration capacity. The sensitivity of Fusr mutants to oxidative stress could be associated with loss of viability due to iron-mediated DNA damage in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. We argue that understanding the specific nature of antibiotic resistance fitness costs in different environments may be a generally useful approach in identifying physiological processes that could serve as novel targets for antimicrobial agents.

Translation elongation factor G (EF-G) is a GTP-binding protein that catalyzes the translocation of peptidyl-tRNA on the ribosome from the A site to the P site (30). After GTP hydrolysis and translocation, EF-G · GDP leaves the ribosome and is regenerated by the spontaneous exchange of GDP for GTP off the ribosome. Fusidic acid is an antibiotic that binds to a complex of EF-G and the ribosome and blocks the release of EF-G · GDP from the ribosome (5, 22). This blockage inhibits further protein synthesis.

Resistance to fusidic acid in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is caused by mutations in fusA, the gene encoding EF-G (21). Similar mutations in fusA are a common cause of fusidic acid resistance in clinical isolates of fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (27). Fusr mutant forms of EF-G, including that encoded by fusA1 studied here, have a reduced rate of nucleotide exchange, and this causes a reduced rate of protein synthesis and cell growth (26). Fusr mutants also have reduced levels of the transcription regulator molecule ppGpp (26). Fusr mutant EF-G apparently interferes with the RelA-dependent synthesis of ppGpp in the ribosomal A site (26). In addition, Fusr mutants have reduced levels of the stress-related sigma factor RpoS (25). The reduced levels of RpoS may also be a consequence of the reduced levels of ppGpp (15, 23) in Fusr mutants. Both ppGpp and RpoS are global transcriptional regulators of gene expression, and consequently, Fusr mutants have phenotypes in addition to translation-rate-related slow growth. These phenotypes include large cell size at division (26) and sensitivity to oxidative stress in vivo (25).

Here we identify reduced production of heme as an important contributing factor to the hypersensitivity of Fusr mutants to oxidative stress. We also show that this has an additional consequence of reducing the rate of respiration in Fusr mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains are derivatives of serovar Typhimurium LT2 (designated as the wild type). This LT2 strain (TT10000) is originally from the lab of John Roth. Transductions were made using P22 HT. Strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) or, where indicated, in minimal M9 medium or nutrient broth (NB) medium (8). The solid medium was Luria agar (LB supplemented with 1.5% agar; Oxoid, Basingstoke, England).

TABLE 1.

Strains used and their genotypes

| Straina | Genotype |

|---|---|

| MM14 | Wild-type S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 |

| MM142 | fusA1 zhb-736::Tn10 |

| JB2110 | fusA1-15 zhb-736::Tn10 |

| MM122 | hemA::lacZ (Kanr) |

| MM123 | fusA1 zhb-736::Tn10 hemA::lacZ (Kanr) |

| MM124 | fusA1-15::zhb-736::Tn10 hemA::lacZ (Kanr) |

| MM125 | relA21::Tn10 hemA::lacZ (Kanr) |

| MM126 | relA1 spoT::Tn10 hemA::lacZ (Kanr) |

| MM46 | katG::pRR10 (Ampr) |

| MM74 | fusA1-15 zhb-736::Tn10 katG::pRR10 (Ampr) |

| MM106 | katE::Tn10 |

| MM107 | fusA1-15 katE::Tn10 |

All strains are derived from Salmonella serovar Typhimurium LT2.

Antibiotics.

Fusidic acid sodium salt was a gift from Leo Pharma, Ballerup, Denmark, and had a final concentration of 800 μg/ml when used in the presence of 1 mM EDTA in the solid medium. Tetracycline (Sigma-Aldrich, Stockholm, Sweden) was used in media at a final concentration of 15 μg/ml.

Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assays.

Bacterial cultures grown in LB to optical densities at 600 nm of 0.2 to 0.4 were treated with 2.5 M hydrogen peroxide (Merck, VWR International, Stockholm, Sweden). To determine viability, aliquots were taken at indicated time points (15, 30, and 45 min), diluted in 0.9% NaCl, and plated onto LB and LB-tetracycline plates. When indicated, cells were exposed to 2,2′-dipyridil (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min prior to treatment with hydrogen peroxide. For δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA; Sigma Aldrich) supplementation experiments, cells were first grown overnight at 37°C in NB medium with and without 50 μg/ml ALA and diluted 100-fold in fresh medium of the same composition. Cells were then grown in NB medium to OD600s of 0.2 to 0.4 with and without 50 μg of ALA/ml (8) before being exposed to 2.5 mM hydrogen peroxide. Viability was assayed as described above.

Catalase activity.

Relative catalase activity was quantified by a colorimetric assay based on the use of dicarboxidine ((γγ′-4,-4′-diamino-3,3′-biphenylylenedioxy) dibutyric acid; Sigma-Aldrich), a sensitive substrate for the detection of peroxidase activity (29). Dicarboxidine is converted into a colored product in a reaction catalyzed by the activity of lactoperoxidase (EC 1.11.1.7) (170 U/mg of protein; Fluka/Sigma-Aldrich); the amount of color developed is directly proportional to the amount of H2O2 present in the medium. Immediately before each experiment, a solution of 50 μg of lactoperoxidase/ml was mixed with an equal volume of 1 mM dicarboxidine. Relative catalase activity in bacterial cultures was assayed according to a previously established method (36) with minor modifications as described here. Cultures were grown overnight in M9 glucose minimal medium, washed, and then resuspended in prewarmed 37°C M9 medium with 0.2% glycerol as a carbon source (we found that the presence of glucose in the medium interfered with the sensitivity of the reaction). The concentration of cells at the start of the assay was 2 × 108 cells/ml. To begin the reaction, H2O2 was added to the bacterial culture to a final concentration of 100 μM. The culture was incubated at 37°C with agitation, and 1-ml samples were taken immediately after the addition of H2O2 and at regular time intervals up to 45 min. Each sample was immediately added to a 200-μl aliquot of the dicarboxidine-lactoperoxidase mixture at room temperature. Within 1 min a stable color developed. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 450 nm. The decrease in the amount of color developed as a function of time is proportional to the amount of H2O2 degraded by catalase and is thus inversely proportional to catalase activity.

β-Galactosidase assays.

Cultures were grown overnight in LB at 37°C and diluted 100-fold in fresh LB medium. Samples were collected from exponentially growing cells (OD600, 0.3) and analyzed as described previously (25). OD420 and OD540 were measured for 16 h at intervals of 5 min in a Bioscreen C machine (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). β-Galactosidase activity units were calculated from the linear part of the OD420 curve for all the samples analyzed, using the formula OD420 − [1.75 × (OD540/OD660)] × time (minutes) × volume of the sample (milliliters).

Competitions in M9 minimal medium supplemented with hydrogen peroxide.

A total of 106 cells of the wild type and the mutant strain per ml were inoculated into M9 minimal medium containing 0.2% glucose supplemented with 70 μM H2O2. For amino acid complementation assays, 1% Casamino Acids, 0.2% glutamine, or 0.2% glutamate (all from Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the minimal medium with 70 μM H2O2. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Counts of viable wild-type and mutant cells were made by taking aliquots, diluting them, and plating them onto LB and LB-tetracycline plates. The competition index is the ratio of mutant/wild-type cells measured in CFU at the end of one cycle of growth competition, where the ratio at time zero is normalized to 1:1.

Heme measurements.

The relative amount of heme in strain MM14 (wild-type strain LT2) versus that in MM142 (fusA1) was measured by a fluorescence heme assay (37). Cultures of the wild type and the fusA1 mutant were grown overnight with shaking in LB, washed, and resuspended in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline. OD600s of the cultures were carefully measured, and appropriate dilutions were made so that different 50-μl aliquots contained numbers of cells corresponding to 0.05 to 1.0 OD600 unit (1 OD600 unit is defined as the number of cells that give an OD600 of 1 in 1 ml). We determined that measurements by OD600 units and dry weight (biomass) gave equivalent results for these strains. Each 50-μl aliquot of cells was mixed with 500 μl of heated 2 M oxalic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated in an oven at 100°C for 30 min. This treatment strips iron from heme, and the resultant protoporphyrin can be measured by fluorescence. A 2 M concentration of oxalic acid was prepared by dissolving 10.08 g of oxalic acid with heating and stirring in 30 ml of water and then bringing the final volume to 40 ml. After 30 min at 100°C, 500 μl of Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (or water) was added to the cell-oxalic acid mixture, and the new mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature. Fluorescence was measured on an SPF-500 corrected-spectrum spectrofluorometer (Aminco-Bowman, Silver Spring, Md.), using Hellma semimicrofluorescence cuvettes (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were excited at 400 nm, and emission was scanned from 200 to 800 nm. Two emission peaks for porphyrin fluorescence were observed, at 608 and 662 nm. We also made, in parallel, fluorescence measurements with crude membrane preparations prepared by French pressing and ultracentrifugation and found the results to be indistinguishable from those made with whole cells treated with oxalic acid (data not shown). We found the oxalic acid method to be simpler, more rapid, and better suited for assaying multiple samples.

Respiration assay.

Cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in LB supplemented with 0.2% glucose. Respiration assays were carried out in a 10-liter (working volume) stirred-tank bioreactor equipped with Wonderware 2000-based software (Belach Bioteknik, Stockholm, Sweden). The bioreactor was filled with 10 liters of LB supplemented with 2% glucose and 3 ml of polypropylene glycol (antifoaming agent; BDH, Poole, United Kingdom). The temperature and pH were adjusted to 37°C and 7, respectively. The bioreactor was inoculated with an appropriate amount of culture to achieve an OD600 of 0.08. The culture used had been grown overnight in a shaking flask of LB supplemented with 0.25% glucose. During the respiration experiment, the OD600 was recorded every 20 min, while dissolved oxygen, carbon dioxide content, and pH were registered continuously. The respiration (oxygen consumption) of the cell population was expressed as the specific respiration rate (q) during one doubling time of the population (the time for the culture's OD600 to increase from 0.2 to 0.4). q is measured in micromoles of O2 per liter per min per OD600. The overall respiration rate of the population, qX (where X is the cell concentration), is in equilibrium with the oxygen transfer rate (OTR) of the bioreactor, i.e., OTR = qX. The bioreactor OTR was calculated from the formula OTR = kLa(c* − c), where kLa is the volumetric mass transfer coefficient, c* is the saturated oxygen concentration, and c is the measured oxygen concentration at a certain time point. Both kLA and c* were determined prior to the experiment by the sulfite oxidation method (2) and by use of the same value parameters (volume, temperature, aeration, stirrer speed, and pressure) applied to the actual culture. During the experiment, the dissolved oxygen concentration was registered continuously and read when the cell concentration (X) corresponded to an OD600 of 0.4. The specific respiration rate was determined by calculating OTR/X.

RESULTS

Fusr mutants reduce HPI and HPII activity.

We have previously shown that Fusr mutants have reduced catalase activity relative to the wild type (25). The relative catalase activity levels associated with the wild type and the strains with the mutations fusA1-15 and fusA1 are 1.00, 0.45, and 0.35, respectively. We asked whether the reduced catalase activity in Fusr mutant JB2110 (fusA1-15) is associated with the HPI or HPII catalases. Isogenic wild-type and fusA1-15 strains (Table 1) were constructed carrying functional knockouts (katG::Tn10 and katE::Tn10) affecting HPI and HPII, respectively. Catalase activity was measured for each strain as the rate of clearance of H2O2 from the growth medium (see Materials and Methods). In strains carrying either one of the catalase genes intact, the presence of the fusA1-15 mutation reduced the catalase activity to less than half the value found in the equivalent fusA+ strain (Table 2). This showed that the fusA1-15 mutation reduced both HPI and HPII catalase activities. We hypothesized that a possible cause of the reduced catalase activity might be the molecule heme, which is a cofactor for both HPI and HPII (3).

TABLE 2.

Impact of fusA1-15 genotype on catalase activity in Serovar Typhimurium strains

| Strain | Genotype | Active catalase(s) | Catalase activity (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM14 | Wild type | HPI + HPII | 100 |

| JB2110 | fusA1-15 | HPI + HPII | 45 |

| MM106 | katE::Tn10 | HPI | 43 |

| MM107 | katE::Tn10 fusA1-15 | HPI | 12 |

| MM46 | katG::pRR10 | HPII | 73 |

| MM74 | katG::pRR fusA1-15 | HPII | 31 |

Results are an average of at least 10 independent assays with a standard error of 5%.

Fusr mutants have reduced expression of hemA.

We wanted to determine whether Fusr mutants were defective in the production of heme. The first committed step in the biosynthesis of heme is the synthesis of the heme precursor ALA. In Salmonella, glutamyl-tRNA reductase, encoded by hemA, converts a small fraction of the cells' charged glutamyl-tRNAGlu to glutamate-semialdehyde. This in turn is converted by glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, encoded by hemL, to ALA. We measured expression of hemA in the wild type and in two Fusr mutants (fusA1 and fusA1-15) by use of a hemA-lacZ operon fusion from Tom Elliott (8). Each Fusr mutant is associated with a decreased level of transcription of the fusion relative to that of the wild type. In strain MM123, the strain with fusA1, the level of hemA-lacZ transcription is only 64% of the wild-type level, while in MM124 (fusA1-15), it is 85% (Table 3). We conclude that Fusr mutants have reduced transcription of hemA.

TABLE 3.

Gene expression from a hemA-lacZ operon fusion in wild-type, Fusr, and relA/spoT mutants

| Strain | Genotypea | β-Galactosidase activityb | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM14 | Wild type | 98.0 | 1.1 |

| MM124 | fusA1-15 | 83.6 | 1.1 |

| MM123 | fusA1 | 62.5 | 2.6 |

| MM125 | relA21::Tn10 | 87.4 | 0.8 |

| MM126 | relA1 spoT::Tn10 | 83.9 | 1.4 |

Relevant genotype; full genotypes are listed in Table 1.

β-Galactosidase activities are given in Miller units (103) and are the average of results of at least four independent assays.

To determine whether the decreased transcription of hemA was due to low levels of ppGpp in the Fusr mutants (26), we measured the expression of the hemA-lacZ fusion in mutants with low ppGpp levels due to mutations in relA (31) and spoT. The relA mutation causes a small reduction in hemA-lacZ expression (Table 3). However, while the fusA1 and relA21::Tn10 strains have similar basal levels of ppGpp, 5 and 7 pmol/OD640 unit, respectively (26), they have very different levels of hemA-lacZ expression, i.e., 64and 89% of wild-type levels, respectively. Also, whereas the fusA1-15 and relA1 spoT::Tn10 strains have very different basal levels of ppGpp, 20 and <1 pmol/OD640 unit, respectively (25, 26), they have similar levels of hemA-lacZ expression, i.e., 85 and 86% of wild-type levels, respectively. We conclude that the decreased level of transcription of hemA in Fusr mutants is not fully explained by their decreased levels of ppGpp.

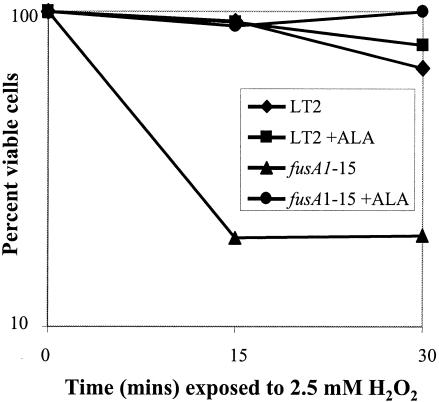

ALA reverses Fusr sensitivity to oxidative stress.

We wanted to determine whether the increased sensitivity of Fusr mutants to oxidative stress caused by exposure to hydrogen peroxide (25) could be attributed to a reduced flow through the heme biosynthesis pathway. A recent study has shown that a Salmonella hemA mutant is very susceptible to hydrogen peroxide (11). We measured the viability of the wild-type strain MM14 and the fusA1-15 strain JB2110 after exposure to hydrogen peroxide when grown with or without the precursor of heme synthesis, ALA. The wild-type bacteria are relatively insensitive to 30 min of exposure to hydrogen peroxide, and, as expected, the presence of ALA did not significantly affect their survival (Fig. 1). In contrast, the fusA1-15 strain (JB2110) was sensitive to this level of hydrogen peroxide, with less than 20% surviving 15 min of exposure. However, the fusA1-15 strain grown with ALA survived as well as the wild type (Fig. 1). The fusA1 strain MM142 was as sensitive in this assay as the strain carrying fusA1-15 (data not shown), and its sensitivity was also reversed by growth in the presence of ALA. The effect of ALA in reversing sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide supports the hypothesis that this sensitivity is due to a low level of heme in the Fusr mutant.

FIG. 1.

Effect of H2O2 on bacterial viability of the wild type and a Fusr mutant as a function of the presence or absence of ALA, a precursor in the heme biosynthesis pathway. The standard error of these measurements is ±10% for the wild type and ±4% for the fusA1-15 mutant.

Media dependence of Fusr sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide.

In the ALA assay described above, cells were grown in a rich LB medium. We noted that in LB, the extreme sensitivity to H2O2 of strains carrying fusA1, previously noted in M9 medium (25), is partly ameliorated. We asked which constituent of LB medium was responsible for this reversal of sensitivity. We made these assays as pairwise competitions between the wild type and Fusr mutants because this is a very sensitive way to measure relative improvements in survival or growth rate. Note that no ALA was added in these assays. We found that the addition of Casamino Acids to M9 glucose minimal medium ameliorated the fusA1 mutant's sensitivity to H2O2 (Table 4). The pathway of heme biosynthesis begins with the conversion of glutamyl-charged tRNAGlu by the product of the hemA gene to glutamate-1 semialdehyde. We considered the possibility that in Fusr mutants, the ameliorating effect of Casamino Acids might be due to the fact that they increase the level of charged glutamyl-tRNAGlu available for the heme biosynthesis pathway. Accordingly, we added several individual amino acids as a supplement to M9 glucose minimal medium with H2O2 and measured the relative fitness of the wild-type and fusA1 strains in a growth competition assay. The addition of glutamine or glutamate, but not proline, histidine, or tryptophan, had a large effect in reducing the sensitivity of the fusA1 strain to H2O2 (Table 4). The magnitude of the increase in competitive ability (fitness) is as great with glutamine alone as it is with Casamino Acids. These data further support the suggestion that the sensitivity of Fusr mutants to H2O2 is, at least in part due to a reduced level of heme synthesis. Furthermore, the positive effect of glutamine and glutamate addition suggested that the earliest step in the synthesis of heme is limited by the availability of charged glutamyl-tRNAGlu for conversion by the hemA product.

TABLE 4.

Medium composition reverses the sensitivity of the Fusr mutation fusA1 to hydrogen peroxidea

| Growth competition medium | CI (fusA1 mutant/WT)b |

|---|---|

| M9 | 3.2 × 10−2 |

| M9 + 70 μM H2O2 | <1 × 10−6 |

| M9 + 70 μM H2O2 + 1% Casamino Acids | 1.4 × 10−3 |

| M9 + 70 μM H2O2 + 0.2% glutamine | 1.4 × 10−3 |

| M9 + 70 μM H2O2 + 0.2% glutamic acid | 3.5 × 10−4 |

Media (10 ml) were inoculated with (per milliliter) 106 cells of the wild-type (MM14) and fusA1 (MM142) strains each and incubated in M9 minimal medium with 0.2% glucose (and the indicated additions) for 18 h at 37°C with shaking. The final cell number was approximately 109/ml, which corresponds to about 10 generations of growth.

The competition index (CI) is the ratio of the number of viable fusA1 mutant CFU to the number of wild-type (WT) CFU after 18 h of competition in each medium. A value of <1 × 10−6 means that no viable cells were recovered. Results are the means of results of three independent assays.

Fluorescence assay of heme levels.

The experiments described above suggest that Fusr mutants have defects in the synthesis of heme. We decided to measure, using afluorescence assay (see Materials and Methods), the relative amount of heme in strain MM14 (wild type) and the Fusr mutant MM142 (fusA1). For each strain, we assayed 10 independent cultures, using 1 OD600 unit of cells for each measurement. The assay is based on stripping the iron from the heme moiety, which leaves a protoporphyrin molecule which fluoresces following excitation at 400 nm (see Materials and Methods). We normalized fluorescence to biomass, measured as either optical density of the starting culture or dry weight of the cells; the two methods gave the same result. We found that the Fusr(fusA1) strain has significantly less heme than the wild-type strain (mean [±standard error of the mean] values of 0.69 [±0.02]and 1.00 [±0.05], respectively). This provides direct evidence that the Fusr phenotype can cause a heme deficiency.

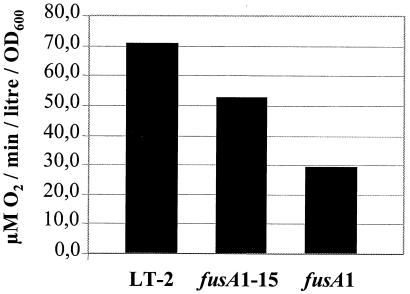

Respiration rate.

Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is a facultative anaerobe (28). It grows faster aerobically because a proton motive force is generated across the bacterial membrane with oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor (19, 28). This process drives the efficient synthesis of ATP (13). Heme-containing cytochromes are an essential part of this respiratory process. We considered the possibility that Fusr mutants, being limited in the amount of heme they produce, might also be defective in aerobic respiration. We measured the rate of oxygen consumption for the wild type and for two Fusr mutants, strains MM142 (fusA1) and JB2110 (fusA1-15), during exponential growth in LB medium. We found that each of the mutants had a significantly lower respiration rate than the wild type (Fig. 2). The respiration rate for the fusA1 mutant is only 41% of that measured for the wild type, and for the fusA1-15 mutant, the respiration rate is 74%. We conclude that these Fusr mutants have a significantly reduced rate of respiration.

FIG. 2.

Respiration (rate of oxygen consumption) in the wild type and two different Fusr mutants. The standard error of these measurements is less than ±2 U for each strain.

Iron-mediated DNA damage.

It was proposed that one consequence of a respiratory deficiency could be the accumulation of NADH, which ultimately provides to free iron the electrons that drive the Fenton reaction (11). Hydroxyl radicals are generated through the Fenton reaction, in which ferrous iron transfers an electron to hydrogen peroxide. These radicals then directly oxidize DNA, producing strand breaks and changes in DNA topology (16). Thus, inhibition of respiration results in an increased amount of cytosolic reductants available to reduce free ferric iron. In the presence of hydrogen peroxide, the ferrous iron thus formed will donate an electron and generate a hydroxyl radical that can damage DNA. This argument is supported by findings that inhibition of any step in the respiratory chain dramatically accelerates the rate at which hydrogen peroxide kills Escherichia coli (16, 33). To test this hypothesis with respect to Fusr strains defective in respiration, we incubated cultures of the wild type and a Fusr mutant with 2,2′-dipyridyl (an iron chelator that penetrates cells and chelates intracellular ferrous iron as well as iron outside the cells). Cultures were incubated together with 2,2′-dipyridyl for 30 min prior to exposure to 2.5 mM H2O2 for 45 min. In cultures treated directly with 2.5 mM H2O2, the percentages of cells viable after 45 min were 41% (wild type) and 20% (Fusr mutant). In contrast, over 70% of the cells in each of the cultures pretreated with 2,2′-dipyridyl survived 45 min of exposure to 2.5 mM H2O2. These results suggest that the decreased survival of the Fusr mutant in the presence of H2O2 is, at least in part, associated with iron-mediated DNA damage, since a decrease in the ferrous iron concentration improves survival.

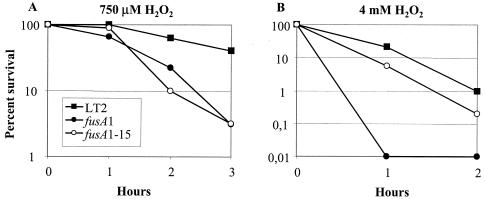

Previous studies have shown that killing by micromolar concentrations of H2O2 (mode I bacterial killing) is mediated by iron-dependent DNA damage, while killing by millimolar H2O2 concentrations (mode II killing) is caused by oxidative damage to multiple targets (17). To compare the relative sensitivities of serovar Typhimurium Fusr mutants to mode I and mode II killing, low (750 μM) and high (4 mM) H2O2 concentrations were used according to a published method (35). After exposure to 750 μM H2O2, 50% of the wild-type cells (MM14) and 3% of cells of the fusA1 mutant (MM142) and the fusA1-15 mutant (JB2110) survived after 3 h of incubation(Fig. 3A). In contrast, exposure to 4 mM H2O2for 2 h reduced the viability of the wild type to 1%, of JB2110 to 0.2%, and of MM142 to a level below the detection limit (<0.001%). Loss of viability after exposure to 4 mM H2O2 is believed to involve oxidative modification of lipids and proteins (17). These results suggest that MM142 (the fusA1 mutant) is hypersensitive to the oxidative damage to DNA, to proteins, and to lipids caused by mode II killing, whereas in the case of JB2110 (the fusA1-15 mutant), the DNA damage caused by Mode I killing might be the more important factor for survival.

FIG. 3.

Mode I versus mode II killing of the wild type and two different Fusr mutants.

DISCUSSION

Fusr strains of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium with mutations in EF-G have reduced catalase activity and are sensitive to oxidative stress caused by H2O2 (25). Detoxification of H2O2 in E. coli and Salmonella is due mainly to two distinct species of catalase. HPI, a bifunctional catalase-hydroperoxidase, is encoded by the katG gene and is active as a tetramer of 81-kDa subunits (9). HPI is transcriptionally induced by OxyR as part of a genetic response to H2O2 (34). HPI activity is observed in the periplasm and in cytoplasmic membrane fractions (14). HPII, a monofunctional catalase, is encoded by the katE gene (24), is active as a tetramer of 78-kDa subunits (10), and is under the control of rpoS (32). HPII is localized in the cytoplasm (14). Here we have shown that the reduced catalase activity in Fusr mutants is associated with a reduction in activity for both HPI and HPII. This association suggested to us that it might reflect a deficiency in something common to both enzymes, such as the iron-binding cofactor heme. We found that expression of hemA, as measured from a hemA-lacZ fusion, is reduced in Fusr mutants, which supports this hypothesis. Salmonella Serovar Typhimurium uses the enzyme glutamyl-tRNA reductase (encoded by hemA) to convert a small fraction of the cells' glutamyl-tRNAGlu to glutamate semialdehyde. This in turn is converted by the enzyme glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase (encoded by hemL) to ALA (1, 12). We found that providing cells with ALA, the precursor in the biosynthesis of heme, improved the viability of Fusr strains exposed to H2O2 to the wild-type level. It has been reported for E. coli that induction of the stringent response (7) results in the RelA-dependent excretion of glutamate from cells (6). Because the levels of ppGpp are disturbed in Fusr mutants (26), we wondered whether the ALA deficiency might be due in part to excretion of glutamate, which possibly leads to insufficient charging of tRNAGlu. We hypothesized that the external addition of either glutamate or glutamine (which can be converted into glutamate inside cells) might decrease the sensitivity of Fusr mutants to H2O2. In support of this, we found that the addition of Casamino Acids, glutamate, or glutamine dramatically improved the survival and growth of the least fit Fusr mutant, relative to the wild type, in the presence of H2O2. Other amino acids tested had no positive or negative effect on the Fusr mutant. Because glutamyl-tRNAGlu is the substrate of the hemA product, a reasonable interpretation of our results is that the insufficient availability of glutamate is, together with reduced transcription of hemA, a factor limiting heme synthesis in Fusr mutants. Finally, we measured relative heme levels by a fluorescence assay and found that a Fusr mutant (with a fusA1 genotype) has significantly less heme than the wild type (69% of that of the wild type). Thus, heme deficiency is a phenotype of Fusr mutants.

Because heme is also a component of the cytochromes involved in respiration (3), we suspected that heme-deficient Fusr mutants might also be defective in respiration. We measured respiration as the rate of oxygen consumption and found that the Fusr mutants had a significantly reduced rate compared to the wild type. Similarly, it was previously shown that a heme-deficient mutant (hemA::Tn10) of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium was both hypersensitive to hydrogen peroxide and respired at half the rate of wild-type cells (11). Mutants with defects in respiration have been shown to suffer from an increased rate of iron-mediated DNA damage (11, 16). Inhibition of any step in the respiratory chain, either by cyanide or by genetic defects in respiratory enzymes, dramatically accelerates the rate at which hydrogen peroxide kills E. coli (18, 33, 38). It has also been established that respiratory blocks accelerate the rate of DNA damage (38). The respiratory blocks do not substantially affect the levels of intracellular free iron or H2O2, indicating that they accelerate damage because they increase the availability of the electron donor. Indeed, a respiratory deficiency causes the accumulation of NADH, which provides to free iron the electrons that drive the Fenton reaction. It was proposed that respiratory inhibitors, by blocking the oxidation of NADH, increase the amount of cytosolic reductants available to reduce free ferric iron. In the presence of hydrogen peroxide, the ferrous iron thus formed will donate an electron and generate a hydroxyl radical that can damage DNA. We found that the presence of 2,2′-dipyridyl, a chelator that penetrates cells and sequesters intracellular ferrous iron as well as iron outside the cells, prior to exposure to H2O2, increases the viability of a Fusr mutant.

Thus, amino acid alterations giving an antibiotic resistance phenotype are, at least in the case of some fusidic acid-resistant mutants, associated with pleiotropic phenotypes which reduce bacterial fitness in a variety of environments. These phenotypes, including the defect in heme biosynthesis and the reduced heme levels identified in this study, are interesting in that they provided insight into the Achilles' heel of resistant strains. Importantly, this Achilles' heel is not limited to a Fusr mutation associated with a severe growth defect in vitro, such as fusA1. We have shown here that a Fusr mutation, fusA1-15, with an in vitro growth rate equivalent to that of the wild type, is also sensitive to oxidative stress. Sensitivity to oxidative stress is of interest because (i) aerobic growth is associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species and (ii) intracellular pathogens such as Salmonella are exposed to reactive oxygen species during the respiratory burst in macrophages, as reviewed previously (20). It has been suggested that a hemA mutation in Salmonella retards growth in an aerobic environment in vivo (4). This shows that the pleiotropic phenotypes associated with antibiotic resistance may result in exploitable weaknesses if one can identify the nature of the fitness costs in relevant environments. The approach taken here, i.e., investigation of the physiological consequences for the bacteria of becoming antibiotic resistant, may be generally useful in providing information that can be applied to identify novel targets or modify treatment therapies and therefore in dealing more effectively with the increasing problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Vetenskapsrådet (The Swedish Research Council) and the European Union to D.H.

We thank Tom Elliott and John Roth for their generosity in providing strains, and Stanley Maloy and Thomas Nyström for valuable discussions and suggestions. We thank Tammy Dailey (University of Georgia, Athens) for her very helpful suggestions on assaying heme, the many members of ICM who gave advice on fluorescence measurements, and the Department of Biochemistry, Uppsala, for generously allowing us access to its fluorescence spectrophotometer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avissar, Y. J., and S. I. Beale. 1989. Identification of the enzymatic basis for δ-aminolevulinic acid auxotrophy in a hemA mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:2919-2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey, J. E., and D. F. Ollis. 1986. Biochemical engineering fundamentals, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, N.Y.

- 3.Beale, S. I. 1996. Biosynthesis of hemes, p. 731-748. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 4.Benjamin, W. H., Jr., P. Hall, and D. E. Briles. 1991. A hemA mutation renders Salmonella typhimurium avirulent in mice, yet capable of eliciting protection against intravenous infection with S. typhimurium. Microb. Pathog. 11:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodley, J. W., F. J. Zieve, L. Lin, and S. T. Zieve. 1969. Formation of the ribosome-G factor-GDP complex in the presence of fusidic acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 37:437-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkovski, A., B. Weil, and R. Kramer. 1995. Glutamate excretion in Escherichia coli: dependency on the relA and spoT genotype. Arch. Microbiol. 164:24-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cashel, M., D. R. Gentry, V. J. Hernandez, and D. Vinella. 1996. The stringent response, p. 1458-1496. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Choi, P., L. Wang, C. D. Archer, and T. Elliott. 1996. Transcription of the glutamyl-tRNA reductase (hemA) gene in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli: role of the hemA P1 promoter and the arcA gene product. J. Bacteriol. 178:638-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claiborne, A., and I. Fridovich. 1979. Purification of the o-dianisidine peroxidase from Escherichia coli B. Physicochemical characterization and analysis of its dual catalatic and peroxidatic activities. J. Biol. Chem. 254:4245-4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claiborne, A., D. P. Malinowski, and I. Fridovich. 1979. Purification and characterization of hydroperoxidase II of Escherichia coli B. J. Biol. Chem. 254:11664-11668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elgrably-Weiss, M., S. Park, E. Schlosser-Silverman, I. Rosenshine, J. Imlay, and S. Altuvia. 2002. A Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium hemA mutant is highly susceptible to oxidative DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 184:3774-3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott, T., Y. J. Avissar, G.-E. Rhie, and S. I. Beale. 1990. Cloning and sequence of the Salmonella typhimurium hemL gene and identification of the missing enzyme in hemL mutants as glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase. J. Bacteriol. 172:7071-7084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gennis, R. B., and V. Stewart. 1996. Respiration, p. 217-261. In F. C. Neidhart, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 2. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 14.Heimberger, A., and A. Eisenstark. 1988. Compartmentalization of catalases in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 154:392-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch, M., and T. Elliott. 2002. Role of ppGpp in rpoS stationary-phase regulation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:5077-5087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imlay, J. A., S. M. Chin, and S. Linn. 1988. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240:640-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imlay, J. A., and S. Linn. 1986. Bimodal pattern of killing of DNA-repair-defective or anoxically grown Escherichia coli by hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 166:519-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imlay, J. A., and S. Linn. 1988. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science 240:1302-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingraham, J. L., O. Maaløe, and F. C. Neidhardt. 1983. Growth of the bacterial cell. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- 20.Janssen, R., T. van der Straaten, A. van Diepen, and J. T. van Dissel. 2003. Responses to reactive oxygen intermediates and virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Microbes Infect. 5:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johanson, U., and D. Hughes. 1994. Fusidic acid-resistant mutants define three regions in elongation factor G of Salmonella typhimurium. Gene 143:55-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurberg, M., O. Kristensen, K. Martemyanov, A. T. Gudkov, I. Nagaev, D. Hughes, and A. Liljas. 2000. Structure of a mutant EF-G reveals domain III and possibly the fusidic acid binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 303:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loewen, P. C., B. Hu, J. Strutinsky, and R. Sparling. 1998. Regulation in the rpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Can J. Microbiol. 44:707-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loewen, P. C., and B. L. Triggs. 1984. Genetic mapping of katF, a locus that with katE affects the synthesis of a second catalase species in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 160:668-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macvanin, M., J. Björkman, S. Eriksson, M. Rhen, D. I. Andersson, and D. Hughes. 2003. Fusidic acid-resistant mutants of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with low fitness in vivo are defective in RpoS induction. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3743-3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macvanin, M., U. Johanson, M. Ehrenberg, and D. Hughes. 2000. Fusidic acid-resistant EF-G perturbs the accumulation of ppGpp. Mol. Microbiol. 37:98-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagaev, I., J. Bjorkman, D. I. Andersson, and D. Hughes. 2001. Biological cost and compensatory evolution in fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40:433-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neidhardt, F. C., J. L. Ingraham, and M. Schaechter. 1990. Physiology of the bacterial cell: a molecular approach. Sinauer, Sunderland, Mass.

- 29.Paul, K. G., P. I. Ohlsson, and N. A. Jonsson. 1982. The assay of peroxidases by means of dicarboxidine on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay level. Anal. Biochem. 124:102-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodnina, M. V., A. Savelsbergh, V. I. Katunin, and W. Wintermeyer. 1997. Hydrolysis of GTP by elongation factor G drives tRNA movement on the ribosome. Nature 385:37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudd, K. E., B. R. Bochner, M. Cashel, and J. R. Roth. 1985. Mutations in the spoT gene of Salmonella typhimurium: effects on his operon expression. J. Bacteriol. 163:534-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sak, B. D., A. Eisenstark, and D. Touati. 1989. Exonuclease III and the catalase hydroperoxidase II in Escherichia coli are both regulated by the katF gene product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3271-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soballe, B., and R. K. Poole. 2000. Ubiquinone limits oxidative stress in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 146:787-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Storz, G., L. A. Tartaglia, and B. N. Ames. 1990. The OxyR regulon. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 58:157-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Testerman, T. L., A. Vazquez-Torres, Y. Xu, J. Jones-Carson, S. J. Libby, and F. C. Fang. 2002. The alternative sigma factor sigmaE controls antioxidant defences required for Salmonella virulence and stationary-phase survival. Mol. Microbiol. 43:771-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winquist, L., U. Rannug, A. Rannug, and C. Ramel. 1984. Protection from toxic and mutagenic effects of H2O2 by catalase induction in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat. Res. 141:145-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodard, S. I., and H. A. Dailey. 1995. Regulation of heme biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 316:110-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodmansee, A. N., and J. A. Imlay. 2002. Reduced flavins promote oxidative DNA damage in non-respiring Escherichia coli by delivering electrons to intracellular free iron. J. Biol. Chem. 277:34055-34066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]