Highlights

-

•

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is an uncommon clinical presentation.

-

•

Concurrent hyphema and orbital apex syndrome are rare clinical sequelae.

-

•

Hyphema is postulated due to auto immune vasculitis affecting iris vessel.

-

•

Orbital apex syndrome results from occlusive vasculitis affecting vasculature of optic nerve and extraocular muscles.

-

•

This incidence probably suggests that occlusive vasculitis occurs at more than one site in the affected dermatome.

Keywords: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus, Persistent hyphema, Orbital apex syndrome

Abstract

Introduction

Hyphema and orbital apex syndrome occurring concurrently in a patient with herpes zoster ophthalmicus have not been reported previously. We present a case with these unique findings and discuss the pathogenesis of these conditions and their management.

Presentation of case

A 59-year-old Malay lady with underlying diabetes mellitus presented with manifestations of zoster ophthalmicus in the left eye. Two weeks later, she developed total hyphema, and complete ophthalmoplegia suggestive of orbital apex syndrome. She was treated with combination of intravenous acyclovir and oral corticosteroids, and regained full recovery of ocular motility. Total hyphema persisted, and she required surgical intervention.

Discussion

Hyphema is postulated to occur due to an immune vasculitis affecting the iris vessels. Orbital apex syndrome is probably due to an occlusive vasculitis affecting the vasculature of the extraocular muscles and optic nerve, resulting from a direct invasion by varicella zoster virus or infiltration of perivascular inflammatory cells. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the brain is essential to exclude possibility of local causes at the orbital apex area.

Conclusion

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is an uncommon ocular presentation. Managing two concurrent complications; persistent total hyphema and orbital apex syndrome is a challenging clinical situation. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are essential to prevent potential blinding situation.

1. Introduction

Common ocular complications in herpes zoster ophthalmicus include keratitis, iridocyclitis, and conjunctivitis [1], [2], [3], [4]. Hyphema and orbital apex syndrome are unusual complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus [2], [3].

We report a middle-aged lady who presented with herpes zoster ophthalmicus, complicated with concurrent total hyphema and orbital apex syndrome. Her condition was managed successfully by a combination of medical and surgical intervention. The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [5].

2. Presentation of case

A 59-year-old Malay lady with underlying diabetes mellitus, hypertension and bronchial asthma presented with left herpes zoster ophthalmicus. She developed multiple herpetic vesicles over the left side of her forehead, upper eyelid, nasal bridge, and extending to the tip of nose (Hutchinson’s sign) for three days prior to consultation. It was associated with skin hyperesthesia and eyelid swelling on the affected side. Her premorbid visual acuity was satisfactory.

The visual acuity was 20/20 (OD) and 20/120 (OS) during presentation. Her left upper eyelid was swollen and erythematous. Few vesicles were observed over the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Limited left abduction was observed. There was conjunctival congestion, with numerous punctate epithelial erosions and evidence of iridocyclitis in the anterior chamber. Her pupil was 6-mm dilated and the intraocular pressure was 22 mmHg. The right eye was normal.

Computed tomography scan of the brain revealed normal extra-ocular muscles, with no evidence of orbital cellulitis or cavernous sinus thrombosis. She was treated with oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times per day, intravenous augmentin 1.2 g 8 hourly, ointment acyclovir 5 times per day, topical prednisolone acetate 1% every 2 h, and topical dorzolomide every 8 hourly.

The herpetic vesicles became dry and crusted, forming scars after a week. The swelling and erythema over the left upper eyelid also reduced, and patient was able to open her eye. The visual acuity improved to 20/60 (OS), with minimal improvement of left eye abduction. The anterior chamber inflammation resolved, and the intraocular pressure normalized to 14 mmHg. She was discharged home with oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times per day, tablet augmentin 625 mg 12 hourly, ointment acyclovir, topical prednisolone acetate 1%, and topical dorzolomide.

During follow up a week later, her visual acuity reduced to 20/160 (OS). A partial ptosis, and complete external ophthalmoplegia were noted in the affected eye (Fig. 1). There were no new vesicles overlying the previous scar. The anterior chamber had minimal inflammation. The left pupil was 6 mm in size and non-reactive, with a reverse relative afferent pupillary defect. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed in view of worsening external ophthalmoplegia. Blood investigations were positive for varicella zoster virus immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M.

Fig. 1.

Partial ptosis and limitation of ocular motility in all gazes.

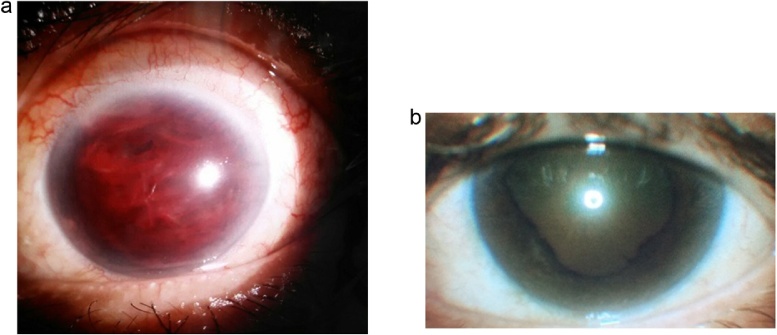

The next day, her visual acuity was deteriorated to perception of light, due to development of a spontaneous total hyphema in the affected eye (Fig. 2a). The intraocular pressure increased to 25 mmHg. She had no bleeding tendencies and blood coagulation profile was normal. The brain MRI showed abnormal enhancement of the perineural sheath of the left optic nerve. There was no evidence of cavernous sinus thrombosis or orbital cellulitis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

(a) Taotal hyphema of the left eye. (b) The pupil was dilated and irregular, with posterior synechiae formation.

Fig. 3.

Brain MRI shows abnormal enhancement of the perineural sheath of the left optic nerve.

She was diagnosed with left herpes zoster ophthalmicus complicated with hyphema and orbital apex syndrome. Intravenous acyclovir 500 mg 8 hourly and oral prednisolone 65 mg daily were commenced by the infectious disease team. Oral tranexamic acid 500 mg 8 hourly was added to prevent subsequent bleeding, and topical brimonidine 8 hourly was also prescribed to stabilize the intraocular pressure.

After two weeks of medical treatment, the total hyphema still showed no sign of resolution. Thus, an anterior chamber washout was performed. Postoperatively, there were no residual blood clots in the anterior chamber. No rubeosis was observed at the iris or angle structure, and the intraocular pressure had normalized to 12 mmHg.

She was discharged home on day two after surgical intervention with oral acyclovir, oral prednisolone, ointment acyclovir, topical prednisolone acetate 1% and topical dorzolomide. She was also started on oral gabapentin and carbamazepine to control symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia.

During follow-up at six weeks later, the visual acuity in the involved eye had improved to 20/120 (OS) and she had regained full ocular motility. The left pupil remained 6-mm dilated, with few areas of posterior synechiae (Fig. 2b). There were occasional cells in the anterior chamber, iris pigments on the anterior lens capsule and a posterior subcapsular cataract. The intraocular pressure remained stable at 16 mmHg. The oral prednisolone was tapered gradually and discontinued after six weeks. Her trigeminal neuralgia had reduced in frequency, and she was able to stop gabapentin and carbamazepine. She completed a twelve-week course of oral acyclovir, and she remains well up to now.

3. Discussion

Our patient presented with classical signs of herpes zoster ophthalmicus that included uveitis, increased intraocular pressure and trabeculitis. Unfortunately, she developed hyphema and orbital apex syndrome two weeks later. These complications can occur immediately, weeks later or months to years after the cutaneous eruption.

Uveitis occurs in 46.6% of herpes zoster ophthalmicus, as reported by Yawn et al. in a cohort study involving 2035 patients [4]. The exact mechanism is unclear. It is postulated that active viral invasion to the uveal tissue results in an immunologic response [6]. Herpetic anterior uveitis is characterized by acute uveitis, associated with iris atrophy and elevated intraocular pressure early in the course of the disease [7].

Trabeculitis causes raised intraocular pressure in this illness. However, it responds rapidly to anti-inflammatory treatment [6]. Our patient had an early rise of intraocular pressure which was managed with a combination of topical corticosteroids and intraocular pressure lowering agents. Her raised intraocular pressure was compounded by persistent hyphema. Tugal-Tutkun and associates reported that elevation of intraocular pressure was observed in 51% of their cases, but only two patients required long term anti-glaucoma therapy [7].

Hyphema following herpes zoster infection is rare [3], [8], [9]. It is postulated that vasculitis results in occlusion of the iris vessels, leading to ischemia and hyphema [8]. This hypothesis has been supported by iris fluorescein angiography. Recently, Okunuki et al. described a case of severe hyphema following herpes zoster ophthalmicus, which was successfully treated medically [9]. In contrast, our patient was treated surgically for a non-resolving severe hyphema.

The clinical diagnosis of orbital apex syndrome requires optic neuropathy associated with complete ophthalmoplegia. Most reported cases of orbital apex syndrome following herpes zoster ophthalmicus described the illness in patients aged above 60 years old [2], [10], [11]. The risk is reported to be equal in immune-competent and immune-incompetent individuals [2]. The onset of ophthalmoplegia is variable, from days to weeks after onset of the herpetic rash [11], [12]. Absence of proptosis can be a misleading clinical sign, as observed in our patient. It is interesting to note that orbital apex syndrome resulting from herpes zoster ophthalmicus is not commonly associated with proptosis [11].

Radiological imaging complements clinical diagnosis in cases of orbital apex syndrome. Lee et al. reported orbital myositis and enhancement of the retro-orbital optic nerve sheath on MRI in their case of orbital apex syndrome following herpes zoster ophthalmicus [13]. Diffuse inflammation of the orbital cavity, ocular muscles, and optic nerve on the affected side was also described by Shirato et al. [11]. Sanjay et al. reported that abnormal enlargement of the extra-ocular muscles was observed on MRI in 33% of the cases, while 17% of cases displayed signs of orbital soft tissue swelling [2]. Our patient’s MRI findings were similar to that of Wang et al., who described isolated optic nerve involvement in their case series of orbital apex syndrome following herpes zoster ophthalmicus infection [12].

Direct invasion by varicella zoster virus and perivascular inflammatory cells are postulated to lead to occlusive vasculitis. An autopsy report by Lexa et al. confirmed evidence of inflammatory cell invasion into the optic nerve sheath and ischemic changes within the optic nerve axons in a patient with herpes zoster ophthalmicus complicated with orbital apex syndrome [14]. Chang-Godinich et al. postulated that diffuse orbital soft tissue edema leads to direct compression of the cranial nerves [15].

Isolated cases of hyphema or orbital apex syndrome complicating herpes zoster ophthalmicus had been reported in the literature [2], [3], [8], [9], [10], [11]. In contrast, our patient developed both conditions concurrently. This incidence probably suggests that occlusive vasculitis occurs at more than one site in the affected dermatome. The possible pathophysiology had been described earlier [8], [14], [15].

The mainstay of treatment of disseminated herpes zoster ophthalmicus is intravenous acyclovir and systemic corticosteroids [2], [9], [12], [13]. Infectious disease specialist and ophthalmologist play important roles in managing the disease. Corneal ulcer and optic atrophy are known visual threatening sequelae. Treatment should be aggressive and aimed at the primary cause.

A review by Sanjay et al. observed that complete or near-complete resolution of ophthalmoplegia occurred in 65% of the cases within a period of two weeks to 1.5 years [2]. Shirato et al. described a case that had progressed to optic atrophy [11]. Our patient achieved complete resolution of ophthalmoplegia after six weeks of treatment. However, her cataract worsened, which may be a complication of uveitis or due to prolonged corticosteroid usage. She also had persistent anisocoria, as described in other reports [11], [13]. Our patient’s optic nerve function tests are within normal limits, and her optic disc remains pink.

4. Conclusion

Concomitant hyphema and orbital apex syndrome are rare sequela of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Prompt diagnosis and early treatment are essential to reduce the ocular morbidity. The management of disseminated disease should adopt a multi-disciplinary approach.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

There is no source of funding to disclose.

Ethical approval

Ethics committee approval was not required to publish this case report.

Consent

Written and signed informed consent from the patient has been obtained.

Author contribution

OK, ETLM – primary authors.

SI, ZE, MJ, RAMN, LSAT, BAM, TJ – had involved in clinical management of the patient.

ZE, SI – supervised and edited the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Dr. Ismail Shatriah.

References

- 1.Weinberg J.M. Herpes zoster: epidemiology, natural history, and common complications. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007;57(6):130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanjay S., Chan E.W., Gopal L., Hegde S.R., Chang B.C. Complete unilateral ophthalmoplegia in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2009;29(4):325–337. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181c2d07e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong D.S., Raizman M.B. Spontaneous hyphema associated with anterior uveitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1993;77(10):635–638. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.10.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yawn B.P., Wollan P.C., St Sauver J.L., Butterfield L.C. Herpes zoster eye complications: rates and trends. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016;88(6):562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green L.K., Pavan-Langston D. Herpes simplex ocular inflammatory disease. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2006;46(2):27–37. doi: 10.1097/00004397-200604620-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tugal-Tutkun I., Ötük-Yasar B., Altinkurt E. Clinical features and prognosis of herpetic anterior uveitis: a retrospective study of 111 cases. Int. Ophthalmol. 2010;30(5):559–565. doi: 10.1007/s10792-010-9394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akpek E.K., Gottsch J.D. Herpes zoster sine herpete presenting with hyphema. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2000;8(2):115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okunuki Y., Sakai J., Kezuka T., Goto H. A case of herpes zoster uveitis with severe hyphema. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14(1):74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arda H., Mirza E., Gumus K., Oner A., Karakucuk S., Sırakaya E. Orbital apex syndrome in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. Med. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/854503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirato S., Oshitari T., Hanawa K., Adachi-Usami E. Magnetic resonance imaging in case of cortical apex syndrome caused by varicella zoster virus. Open Ophthalmol. J. 2008;2(1):109–111. doi: 10.2174/1874364100802010109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang A.-G., Liu J.H., Hsu W.M., Lee A.F., Yen M.Y. Optic neuritis in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2000;44(5):550–554. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(00)00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee C.Y., Tsai H.C., Lee S.S., Chen Y.S. Orbital apex syndrome: an unusual complication of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015;15(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0760-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lexa F.J., Galetta S.L., Yousem D.M., Farber M., Oberholtzer J.C., Atlas S.W. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus with orbital pseudotumor syndrome complicated by optic nerve infarction and cerebral granulomatous angiitis: MR-pathologic correlation. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1993;14(1):185–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang-Godinich A., Lee A.G., Brazis P.W., Liesegang T.J., Jones D.B. Complete ophthalmoplegia after zoster ophthalmicus. J. Neuroophthalmol. 1997;17(4):262–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]