Abstract

Q fever is a worldwide zoonotic infection caused by the obligate intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii that can course with acute or chronic disease.

This series describes 7 cases of acute Q fever admitted in a Portuguese University Hospital between 2014 and 2015.

All cases presented with hepatitis and had epidemiological history. Diagnosis was done by PCR on majority (5) and by serology and PCR in only 2.

Serological tests can be negative in the initial period of the disease. Molecular biology methods by polymerase chain-reaction are extremely important in acute disease, allowing timely diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Coxiella burnetii, Acute q fever, Hepatitis

Introduction

Q fever is a worldwide zoonotic infection caused by the obligate intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii [1], [2] that can course with acute or chronic disease [3].

The most commonly identified sources of human infection are farm animals such as cattle, goats and sheep, [4] and transmission results mainly from inhalation of contaminated aerosols [5].

The acute clinical manifestations of Q fever range from asymptomatic seroconversion (50%–90% of patients) to severe disease [1], [2]. Symptomatic patients usually present with an influenza-like illness with varying degrees of pneumonia and hepatitis [3].

Immunofluorescence assay is the reference method for serodiagnosis of Q fever. There is also evidence of high sensitivity and specificity of PCR in specialized laboratories [5].

The recommended treatment for acute disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days, but starting antibiotic after the third day of disease may not change the outcome [3].

This series describes 7 cases of acute Q fever admitted in a Portuguese University Hospital between 2014 and 2015. Our aim is to describe the clinical presentation of this disease in our setting, highlighting the difficulties of achieving the diagnosis, due to its unspecific clinical behaviour, the absence of a clear history of zoonotic exposure and/or the frequently negative serology early in the course of the disease. We also want to emphasize the importance of molecular methods for timely diagnosis.

Material and methods

This case series includes the patients who fulfilled all the following criteria: age over 18 years, admission to Infectious Diseases Department in an University Hospital in Porto, Portugal, between 2014 and 2015 with the diagnosis of acute Q fever, based on compatible clinical picture and positive serology or PCR during hospital stay or follow up, without an alternative diagnosis.

Patients were identified through our hospital’s patient database and clinical information collected from medical records.

For each case, we report relevant data, such as: prior medical history, epidemiological context for exposure to Coxiella burnetii, disease clinical presentation, laboratory results (Table 1, Table 2), treatment and follow-up.

Table 1.

Relevant epidemiological data and main laboratory results on admission.

| Laboratory parameters | Reference levels | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission date | 02/01/2014 | 28/10/2014 | 30/01/2015 | 13/02/2015 | 26/02/2015 | 03/07/2015 | 04/08/2015 | |

| Day of fever | 8 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 3 | |

| Epidemiological data | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| WBC (×109 cell/L) | 4.0–11.0 × 109L | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.92 | 4.25 | 5.56 | 9.64 | 5.64 |

| PMNL (%) | 53.8–69.8% | 82% | 80% | 84% | 57% | 59.6% | 66.6% | 48% |

| Platelet count (×109 cells/L) | 150–400 × 109L | 164 | 155 | 77 | 115 | 125 | 186 | 107 |

| AST (IU/L) | 10–37 U/L | 332 | 186 | 152 | 82 | 158 | 91 | 76 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 10–37 U/L | 481 | 289 | 271 | 206 | 197 | 125 | 108 |

| SGGT (IU/L) | 10–49 U/L | 571 | 148 | 285 | 132 | 221 | 177 | 38 |

| APT (IU/L) | 30–120 U/L | 238 | 157 | 194 | 113 | 178 | 145 | 85 |

| Total bilirrubin | <1.2 mg/dL | 1.81 | 0.76 | 3.24 | 1.45 | 1.19 | 0.54 | 0.68 |

| Direct bilirrubin | <0.4 mg/dL | 0.91 | 0.25 | 2.11 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

| aPTT | 24.5–36.5 s | 35.9 | 31 | 40 | 31.8 | 43.7 | 35.5 | 32.6 |

| PT | 9.5–14.5 s | 13.2 | 12.2 | 17 | 13 | 13.5 | 12 | 12.4 |

| CRP (mg/L) | <3 mg/L | 145.9 | 103.6 | 240 | 106 | 179 | 148.7 | 88.7 |

WBC: white blood cells; PMNL: polymorphonuclear leukocytes; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; SGGT: serum gamma-glutamyl transferase; APT: alkaline phosphatase level; aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; PT: prothrombin time; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Table 2.

Results of methods used for diagnosis.

| Diagnosis methods | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase | |||||||

| Day of fever | 7 | 5 | 8 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 3 |

| DNA of Coxiella burnetii (PCR) | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Serology | |||||||

| IgM | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| IgG | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Convalescent phase | |||||||

| Time since beginning of fever | 15 days | 1.5 months | 1 month | 2 months | 1 month | 4 months | 2 months |

| Serology | |||||||

| IgM | Negative | Negative | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| IgG | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

Q fever diagnosis was based on serology, using an indirect immunoenzyme assay to test phase II IgG antibodies against Coxiella burnetii in human serum (Delta Biologicals N° DBE-080®), and a real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay targeting the insertion element (IS1111), which detect DNA in blood [14].

Case reports

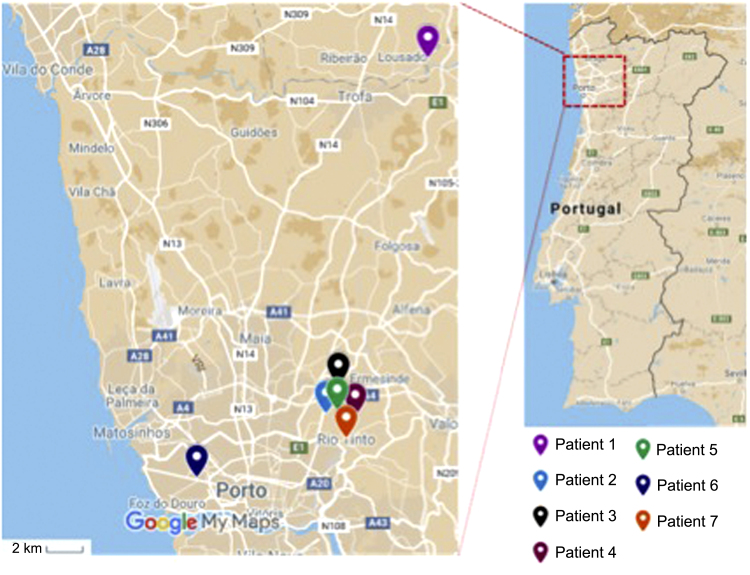

Patient 1, a 47-year-old man who lived in Lousada (Fig. 1), a rural area nearby a sheep farm, was admitted with acute hepatitis in January 2014. He presented with a history of fever, asthenia, vomiting, diarrhoea and choluria for 8 days. He had been prescribed clarithromycin (500 mg/d), 5 days before, without improvement.

Fig. 1.

Overview of cases geographical data.

On physical examination, he was febrile (39 °C), had abdominal tenderness on the right lower quadrant, liver was palpable 2 cm below the costal margin; the remaining physical examination was normal. An abdominal ultrasound showed a hepatomegaly (19 cm) and diffuse steatosis.

His lab results are shown on Table 1. Serologies for HIV, Hepatitis B and C were negative. He was immune to Hepatitis A.

Given the persistence of fever and increased inflammatory markers he was started on cefotaxime. Three days later serology and PCR results were positive for C. burnetii. A diagnosis of acute Q fever was assumed and doxycycline was started.

Echocardiography was unremarkable. Liver biopsy revealed a chronic granulomatous process; granulomas contained lipidic vacuole surrounded by a fibrinoid ring. Patient completed 21 days of antibiotic therapy with full clinical recovery.

Patient 2, a 47-year-old man from Rio Tinto (Fig. 1), who worked in an abattoir, was admitted with a history of fever in October 2014. He presented with a six day history of fever, headache, photophobia, chills, loose stools (without blood, mucus or pus) and vomiting.

At admission, he was febrile (39 °C) and the reminder of physical examination was unremarkable. Blood tests are described in Table 1; serologies for HIV, Hepatitis B and C were negative. Echocardiography showed normal global ventricular systolic function.

Q fever diagnosis was based on the detection of C. burnetii DNA in blood; serology was negative. The patient completed 21 days of doxycycline with full clinical recovery.

During follow- up, repeated serologic test showed positive IgG for C. burnetii.

Patient 3, a 31-year-old man who lived in a rural area in Águas Santas (Fig. 1), with farmers in the surroundings and with no prior medical history, presented to the Emergency Department with a 4-day history of prostration, fever (maximum of 39,4 °C), anorexia, nausea and one episode of vomiting. On admission he was febrile and adynamic but the remaining physical examination was unremarkable. Blood results are shown in Table 1. Viral serologies were negative. Abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatomegaly. Chest radiography was normal. He was admitted to the Infectious Diseases Department in January of 2015.

Patient́s clinical condition progressively worsened and he was put on Ceftriaxone for suspected leptospirosis and admitted in our Intensive/Intermediate Care Unit.

Despite a negative Q fever serology on admission, diagnosis of Q fever was made after a positive PCR for C. burnetii in blood. Other causes of fever and acute hepatitis were excluded.

Oral doxycycline was started on the 3rd day after admission, with clinical improvement. At follow-up he was asymptomatic and repeated serology that was positive (IgG).

Patient 4, a 26-year-old man who lived in a urban area in Águas Santas (Fig. 1), whose father worked in an abattoir, presented to the emergency department in February 2015 with an 8-day history of fever, headache, myalgia and occasional vomiting.

Physical examination was unremarkable except for fever. Blood work is shown on Table 1. Abdominal ultrasound showed hepatosplenomegaly, and chest radiography was normal.

Patient was started on ceftriaxone 2 g for suspected leptospirosis. On the 2nd day after admission, he became asymptomatic. Leptospirosis blood PCR was negative and Coxiella burnetii DNA was positive so doxycycline was started. Patient was discharged at day 5 Ecocardiography did not show any valvular lesions. At follow-up serology became positive (IgG).

Patient 5, a 22-year-old woman who lived in an urban area in Ermesinde (Fig. 1) with sporadic contact with rural areas, and with a personal history of scoliosis and chronic rhinosinusitis, was admitted in February 2015 with a 5-day history of fever, upper abdominal pain, constipation and anorexia. On physical examination she was febrile and had palpable and tender hepatomegaly. Blood tests are shown in Table 1; Abdominal ltrasound showed an enlarged liver (18 cm); chest radiography was normal. On the 2nd day of hospital admission she was put on Ceftriaxone, abdominal symptoms began to improve but fever persisted. PCR was positive for Coxiella burnetii as serologic test, IgG and IgM. Patient was discharged with doxycycline.

Patient 6, a 72-year-old man who lived in a rural area in Porto (Fig. 1), with goats in the backyard (one of them had an abortion 3 weeks earlier), was admitted in July, 2015 with a 7 day history of fever, anorexia and malaise. Besides fever, physical examination was unremarkable.

Blood work is revealed on Table 1. Serologies for HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and C. burnetii were negative.

After 4 days of hospitalization, the patient had a remarkably improvement and was discharged. At follow-up (7 days later), C. burnetii DNA in blood was positive so Q fever was assumed and doxycycline was prescribed. Convalescent serological test showed a positive IgG.

Patient 7, a 31-year-old man who lived in a rural area with goats and rats on the surroundings, in Rio Tinto (Fig. 1), was admitted in August 2015 with the suspicion of leptospirosis He presented with a 3 day history of fever, night sweats and choluria.

On admission, he was febrile (38 °C) and the remainder physical examination was unremarkable. Blood tests are revealed on Table 1. Viral serologies were negative. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasound were normal.

C. burnetii DNA was positive in blood. The First serology for C. burnetii was negative but 1 month later IgG became positive.

The patient completed 21 days of doxycycline with full clinical recovery.

Discussion

This case series describes the epidemiological data, clinical characteristics, diagnostic methods, treatment and follow-up of patients with acute Q fever hospitalized in the Infectious Diseases Department of Centro Hospitalar São João between 2014 and 2015.

Q fever is endemic in Portugal. Unlike in other European countries where there is a trend towards a decrease in the number of cases, in Portugal the numbers have been stable [19], [20].

As already stated, Q fever has a wide spectrum of manifestations that are unspecific, which accounts for the difficulty in the diagnosis and the need for high clinical suspicion. As such, the epidemiological history is of critical importance [5], [6]. In our series, all had positive epidemiological data, mostly regarding contact or close proximity to sheep, cattle or goats, suggesting aerosol inhalation as the main route of transmission. However, excluding patient 2 that worked in an abattoir and patient 6 that reported a sheep abortion, the degree of contact with those animals was minimal in the remaining patients. As such, this important diagnostic clue is often disregarded by patients as relevant and needs to be actively searched by physicians [6], [7].

Regarding clinical presentation, Portuguese studies have described three main clinical manifestations: self-limited febrile illness, hepatitis and pneumonia, being hepatitis more frequent [8], [9], [10], [11], in agreement with our case series. Some authors have suggested that disease presentation is dependent on the mode of transmission, with intraperitoneal inoculation being associated with hepatic involvement [12], [13]. None of the patients of this report had consumed unpasteurized dairy products, contradicting this hypothesis. As described in this case series, patients with hepatic involvement usually present with elevations in liver enzymes and cholestasis. Hepatomegaly, hepatic tenderness and prolonged fever of unknown origin with characteristic granulomas on liver biopsy can also be present [5], [6], as was the case of one patient described. On follow-up, all patients presented normal liver enzymes of note; no patient had evidence of respiratory involvement.

Besides acute hepatitis, all patients presented with fever and five with abdominal symptoms such as, abdominal pain and/or vomiting. Hepatomegaly was also a frequent clinical finding. Usual biological abnormalities observed in acute Q fever were observed in our patients (Table 1): all had elevated C Reactive Protein but no leukocytosis, some presented thrombocitopenia.

Q fever diagnosis usually is done by serological tests. An important characteristic of C. burnetii is its antigenic variation, called “phase variation”. This antigenic shift can be measured and it differentiates acute from chronic Q fever [15], [16]. As all serological diagnosis, serological tests for acute Q fever have to be performed in two samples collected in a range of 2 to 4 weeks. Moreover, if taken early in the course of the disease, the first sample can be negative. This is an important diagnostic limitation: it delays diagnosis and compromises effective treatment in the acute phase. Furthermore, performing exams at 2 timelines are time-consuming for both the patient and health care. This case series exemplifies this method’s limitation on acute disease diagnosis (Table 2): five of the seven patients had negative results on the first sample; the two that were positive presented later (on the ninth and eleventh days of disease).

In order to overcome this problem, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been successfully used to detect C. burnetii DNA on blood. Many authors describe his high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of both acute and chronic infections [5], [16], [17], [18]. The Real Time PCR is currently the gold standard in the direct detection of C. burnetii DNA [18]. The performance of this diagnostic technique in our case series was excellent: all patients tested positive, and all diagnosis were confirmed latter with a positive serology.

Patient’s outcomes are usually favourable and only a small number of patients go on to chronic or life-threatening infection [6]. All the described patients were treated with doxycycline for 14–21 days and showed a favourable evolution, with full recovery of the clinical picture and analytical changes, remaining asymptomatic on follow-up. None of them had valvular changes on echocardiography or other evident risk factors for chronic Q fever.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of Q fever is challenging due to its unspecific manifestations; epidemiological data is the most important clue. Serological tests can be negative in the initial period of the disease. Molecular biology techniques (PCR for the detection of C. burnetiis’s DNA on blood) are important tools in the diagnosis of acute disease, allowing timely diagnosis and treatment. However, there is a need for standardization of these new diagnostic methods.

Reference

- 1.Maurin M., Raoult D. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(October):518–553. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogema B.M., Slot E., Molier M., Schneeberger P.M., Hermans M.H., Van Hannen E.J. Coxiella burnetii infection among blood donors during the 2009 Q-fever outbreak in the Netherlands. Transfusion (Paris) 2012;52:144–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker N.R., Barralet J.H., Bell A.M. Q fever. Lancet. 2006;367:679–688. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins D., Marrie T.J. Seroepidemiology of q fever among cats in new brunswick and prince edward island. Annals New York Acad Sci. 1990;590:271–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fournier P., Marrie T.J., Raoult D. Diagnosis of q fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1823–1834. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1823-1834.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reimer Larry G. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993:193–198. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann J.S., Douglas J.G., Inglis J.M., Leitch A.G. Q fever: person to person transmission within a family. Thorax. 1986;41:974–975. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.12.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmela Carolina, Badura Robert, Valadas Emília. Acute Q fever in Portugal. Epidemiological and clinical features of 32 hospitalized patients. Germs. 2012;2(June (2)):43–59. doi: 10.11599/germs.2012.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendes M.R., Carmona M.H., Malva A., Souza R.D. Febre q–estudo retrospectivo. Revista Portuguesa de Doenças Infecciosas. 1989;12(3):149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira J., Malcata Sá R., Ventura C., Alonso A. I Congresso Luso Galaico. V Congresso Nacional de Doenças Infecciosas; Porto, 15–19 de Outubro de: 2000. Febre Q – revisão de 53 casos (1987–1999) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ana Sofia Santos., Febre Q: do diagnóstico à investigação ecoepidemiológica de Coxiella burnetii no contexto da infeção humana. Repositório INSA, 2016.

- 12.La Scola B., Lepidi H., Raoult D. Pathologic changes during acute Q fever: influence of the route of infection and inoculum size in infected guinea pigs. Infect Imm. 1997;65(6):2443–2447. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2443-2447.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marrie T.J., Stein A., Janigan D., Raoult D. Route of infection determines the clinical manifestations of acute Q fever. J Infect Dis. 1996;173(2):484–487. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen D.R., Hartman L.J., Loveless B.M., Frye M.S., Shipley M.A., Bridge D.L. Detection of biological threat agents by real-time PCR: comparison of assay performance on the R.A.P.I.D., the Light Cycler, and the smart Cycler platforms. Clin Chem. 2006;52:141–145. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.052522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson A., Bijlmer H., Fournier P.E., Graves S., Hartzell J., Kersh G.J. Diagnosis and management of q fever, 2013: recommendations from CDC and the q fever working group. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1. (RR-03) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupuis G., Peter O., Peacock M., Burgdorfer W., Haller E. Immunoglobulin responses in acute Q fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22(4):484–487. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.4.484-487.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein A., Raoulti D. Detection of coxiella burnetii by DNA amplification using polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;(September):2462–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2462-2466.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klee S.R., Tyczka J., Ellerbrok H., Franza T., Linke S., Baljer G. Highly sensitive real-time PCR for specific detection and quantification of Coxiella burnetii. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Direção-Geral da Saúde. Doenças de Notificação Obrigatória (1999 a 2013). Portugal, 2015.

- 20.ECDC . 2014. Surveillance Report Annual epidemiological report–Emerging and vector-borne diseases. [Google Scholar]