Abstract

Prevotella phocaeensis sp. nov. strain SN19T (= DSM 103364) is a new species isolated from the gut microbiota of patient with colitis due to Clostridium difficile. Strain SN19T is Gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria, strictly anaerobic, nonmotile and non–endospore forming. The predominance fatty acid is hexadecanoic acid. Its 16S rRNA showed a 97.70% sequence identity with its phylogenetically closest species, Prevotella oralis. The genome is 2 922 117 bp long and contains 2486 predicted genes including 56 RNA genes.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, culturomics, gut microbiota, Prevotella phocaeensis, taxonogenomics

Introduction

The human gut includes approximately 1014 microorganisms, known as the intestinal microbiota, and contains four main phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria [1]. This microbial ecosystem contributes to the host's health [1], [2], [3] but may also be involved in human disease [1], [4], [5]. Because intestinal conditions are difficult to reproduce in the laboratory, particularly a strongly reduced environment with a quasi absence of oxygen, most of this microbial universe has not yet been cultivated [1]. However, strict anaerobic microbes should not be neglected because they are the mainstay of the healthy mature anaerobic gut microbiota indispensable for a healthy life [6].

Several studies have already been conducted to identify the microorganisms included in this ecosystem by using both culture methods and culture-independent methods, such as sequencing of the gene encoding 16S ribosomal RNA and metagenomics. The latter sheds light on several unknown microorganisms. However, genomics identifies DNA or RNA sequences but not living microbes.

Recently in our laboratory the culturomics and taxonogenomics approaches were established to unravel gut microbiota diversity while overcoming biases associated with culture-independent techniques. Through this innovative strategy associating several culture conditions, mass spectrometry and molecular biology, more than 200 new species have been isolated from the human gut [7]. Using this approach, we isolated for the first time Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T (= CSUR P2259 = DSM 103364) from the gut of a woman infected by Clostridium difficile. Here we describe its phenotypic features along with the genome annotation and comparison with the closest species.

Material and Methods

Sample information

A stool specimen was collected from an 81-year-old white woman with Clostridium difficile infection (toxin B, ribotype 027 negative) at La Timone hospital (Marseille, France) in November 2015. The stool sample was collected in sterile plastic containers and stored at −80°C once aliquots were made. Consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the Institut Fédératif de Recherche 48 (Faculty of Medicine, Marseille, France) under agreement number 09-022. The patient was treated with metronidazole; the outcome was a full recovery and no relapse.

Growth conditions

Growth of this isolate was obtained after 5 days' incubation in a 5% sheep's blood– and 5% rumen-enriched medium in anaerobic atmosphere at 37°C. This isolate was then subcultured on 5% sheep's blood–enriched Columbia agar (COS; bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). The growth environment of strain SN19T was determined by testing different temperatures (25, 28, 30, 37 and 56°C) in aerobic and anaerobic (anaeroGEN; Oxoid, Thermo Scientific, Dardilly, France) conditions. Salinity (5–100 g/L) and pH (6–8.5) were also tested.

Strain identification

Matrix-assisted desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis of strains SN19T was performed on a MicroFlex mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Leipzig, Germany) as previously described [8]. The acquired spectrum was then loaded into the MALDI Biotyper Software (Bruker) and analyzed as previously described [8] by using the standard pattern-matching algorithm, which compared the spectrum acquired with that present in the library (Bruker database and ours, constantly updated), including 7463 species. Score values of ≥1.7 but <2 indicated identification beyond the genus level, and score values of ≥2.0 indicated identification at the species level. Scores of <1.7 were interpreted as not relevant.

In this case, we performed the 16S rRNA gene sequencing. For DNA extraction, we used the EZ1 DNA Tissue Kit using Biorobot EZ1 Advanced XL (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). The amplification of the 16s rRNA gene was carried out using PCR technology and universal primers FD1 and RP2 [8] (Eurogentec, Angers, France). Then we realized the purification, sequencing and assembly of the amplified products as previously described [9]. Sequences of 16S rRNA genes were confronted with those which are available in GenBank by BLASTn (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/). When the percentage of identity was <98.7%, the studied strain was considered to be a new species [10].

Phylogenetic analysis

A custom Python script was used to automatically retrieve all species from the same family of the new species and download 16S sequences from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) by parsing NCBI eUtils results and the NCBI taxonomy page. It only keeps sequences from type strains. In case of multiple sequences for one type strain, it selects the sequence obtaining the best identity rate from the BLASTn alignment with our sequence. The script then separates 16S sequences in two groups: one containing the sequences of strains from the same genus (group a), and one containing the others (group b). It only keeps the 15 closest strains from group a and the closest one from group b. If it is impossible to get 15 sequences from group a, the script selects more sequences from group b to get at least nine strains from both groups.

Phenotypic and biochemical characterization

Biochemical characterization and sporulation

For biochemical characterization of strain SN19T, we used gallery API. ZYM, API Rapid ID 20NE and API 50CH (bioMérieux) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then we tested catalase (bioMérieux) and oxidase (BD BBL DrySlide; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) activities. To determine sporulation, thermal shock was performed on a bacterial suspension of this strain at 80°C for 20 minutes; then this suspension was seeded Columbia blood agar. Incubation was done for 72 hours under anaerobic conditions at different temperatures: 28, 37, 42 and 56°C.

Fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) analysis by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS)

Cellular FAME analysis was performed by GC/MS. Two samples were prepared with approximately 30 mg of bacterial biomass per tube collected from several culture plates. FAME were prepared as described by Sasser [11]. GC/MS analyses were carried out as previously described [12]. Briefly, fatty acid methyl esters were separated using an Elite 5-MS column and monitored by mass spectrometry (Clarus 500-SQ 8 S; Perkin Elmer, Courtaboeuf, France). A spectral database search was performed using MS Search 2.0 operated with the Standard Reference Database 1A (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, USA) and the FAMEs mass spectral database (Wiley, Chichester, UK).

Microscopy

Mobility and Gram staining of strain SN19T were determined using an optical microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with a 40× and 100× oil-immersion objective lens, respectively. In order to observe the cells' morphology, they were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for at least 1 hour at 4°C. A drop of cell suspension was deposited for approximately 5 minutes on glow-discharged formvar carbon film on 400 mesh nickel grids (FCF400-Ni; Electron Microscopy Sciences (EMS), Hatfield, PA, USA). The grids were dried on blotting paper, and the cells were negatively stained for 10 seconds with 1% ammonium molybdate solution in filtered water at room temperature. Electron micrographs were acquired with a Tecnai G20 Cryo (FEI Company, Limeil-Brevannes, France) transmission electron microscope operated at 200 keV.

Antibiotic susceptibility

The in vitro antibiotic susceptibility was tested by disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar with 5% sheep's blood for the following antibiotics: imipenem 10 μg, penicillin G 10 μg, ciprofloxacin 5 μg, teicoplanin 30 μg, gentamycin 500 μg, rifampicin 30 μg, ceftriaxone 30 μg, clindamycin 15 μg, colistin 50 μg, doxycycline 30 μg, erythromycin 15 μg, fosfomycin 50 μg, oxacillin 5 μg, metronidazole 4 μg and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 25 μg.

DNA extraction and genome sequencing

After pretreatment by lysozyme incubation at 37°C, DNA was extracted on the EZ1 biorobot (Qiagen) with EZ1 DNA tissues kit. The elution volume was 50 μL. The genomic DNA (gDNA) was quantified by a Qubit assay with a high-sensitivity kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USAUSA) at 152.3 ng/μL.

gDNA of strain SN19T was sequenced by MiSeq Technology (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with the mate pair strategy. The gDNA was barcoded in order to be mixed with 11 other projects with the Nextera Mate Pair sample prep kit (Illumina). The mate pair library was prepared with 1.5 μg of gDNA using the Nextera mate pair Illumina guide. The gDNA sample was simultaneously fragmented and tagged with a mate pair junction adapter. The pattern of the fragmentation was validated on an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a DNA 7500 labchip. The DNA fragments ranged in size from 1.5 to 11 kb, with an optimal size at 7.472 kb. No size selection was performed, and 600 ng of tagmented fragments were circularized. The circularized DNA was mechanically sheared to small fragments with an optimal at 954 bp on the Covaris device S2 in T6 tubes (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA). The library profile was visualized on a High Sensitivity Bioanalyzer LabChip (Agilent Technologies), and the final concentration library was measured at 6.08 nmol/L. The libraries were normalized at 2 nM and pooled. After a denaturation step and dilution at 15 pM, the pool of libraries was loaded onto the reagent cartridge and then onto the instrument along with the flow cell. Automated cluster generation and sequencing run were performed in a single 39-hour run at a 2 × 151 bp read length. The total information of 2.9 Gb was obtained from a 297K/mm2 cluster density with a cluster passing quality control filter of 97% (5 808 000 passing filter paired reads). Within this run, the index representation for strain SN19T was determined at 8.47%. The 492 215 paired reads were trimmed.

Genome annotation and comparison

Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal [13] with default parameters, but the predicted ORFs were excluded if they spanned a sequencing gap region (contain N). The predicted bacterial protein sequences were searched against the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) using BLASTP (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; E value 1e-03, coverage 0.7 and identity percentage 30%). If no hit was found, it was searched against the NR database using BLASTP with E value of 1e-03 coverage 0.7 and an identity percentage of 30%, and if the sequence length was smaller than 80 aa, we used an E value of 1e-05. The tRNAScanSE tool [14] was used to find tRNA genes, whereas ribosomal RNAs were found by using RNAmmer [15]. Lipoprotein signal peptides and the number of transmembrane helices were predicted using Phobius [16]. ORFans were identified if all the BLASTP performed did not give positive results (E value smaller than 1e-03 for ORFs with a sequence size larger than 80 aa or an E value smaller than 1e-05 for ORFs with sequence length smaller than 80 aa). Such parameter thresholds have already been used in previous studies to define ORFans.

Genomes were automatically retrieved from the 16S RNA tree using Xegen software (PhyloPattern) [17]. For each selected genome, the complete genome sequence, proteome genome sequence and ORFeome genome sequence were retrieved from the NCBI's FTP site. All proteomes were analyzed with proteinOrtho [18]. Then for each couple of genomes a similarity score was computed. This score is the mean value of nucleotide similarity between all couple of orthologues between the two genomes studied (average genomic identity of orthologous gene sequences, AGIOS) [19]. An annotation of the entire proteome was performed to define the distribution of functional classes of predicted genes according to the clusters of orthologous groups of proteins (using the same method as for the genome annotation). To evaluate the genomic similarity among studied Prevotella strains, we determined two parameters, digital DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH), which exhibits a high correlation with DDH [20], [21] and AGIOS [19], which was designed to be independent from DDH. Annotation and comparison processes were performed in the Multi-Agent software system DAGOBAH [22], which includes Figenix [23] libraries that provided pipeline analysis. The genome of strain SN19T was compared with the one of closest species such as Prevotella oralis (AEPE00000000), Prevotella micans (BAKH00000000), Prevotella stercorea (AFZZ00000000), Prevotella timonensis (CBQQ000000000), Prevotella shahii (BAIZ00000000), Prevotella loescheii (ARJO00000000), Prevotella saccharolytica (BAKN00000000), Prevotella oulorum (ADGI00000000) and Prevotella marshii (AEEI00000000).

Results

Classification and features

Strain identification by MALDI-TOF MS and 16S rRNA sequencing

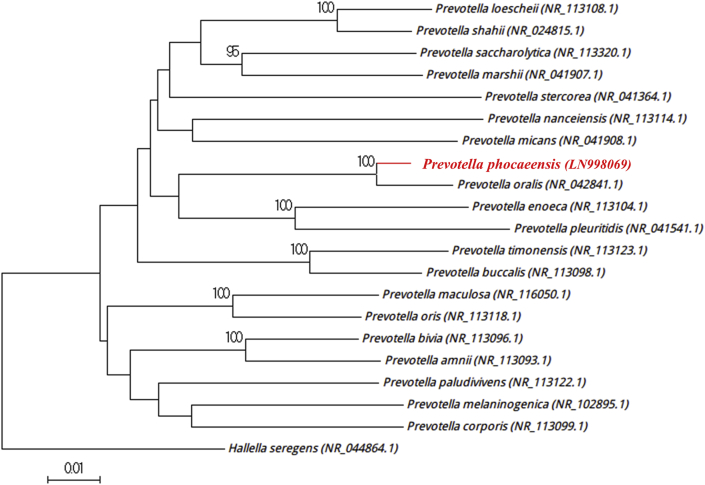

Strain SN19T was first isolated in November 2015 from the stool that was used to diagnose a C. difficile infection, stored at −80°C and cultured on Columbia agar enriched with 5% sheep's blood at 37°C during 5 days under anaerobic conditions. The MALDI-TOF spectrum (Fig. 1) did not match either Bruker's database or our database, and was consequently added (http://www.mediterranee-infection.com/article.php?laref=256&titre=urms-database). Then the 16S rRNA gene sequencing demonstrated that the type strain Prevotella oralis ATCC 33269 (GenBank accession no. NR_042841.1) is the phylogenetically closest to strain SN19T and showed a 97.70% sequence identity with it (Fig. 2). This value was lower than the 98.7% 16S rRNA gene sequence threshold advised by Stackebrandt and Ebers [10] to describe a new species without carrying out DNA-DNA hybridization. Therefore, we propose strain SN19T as the type strain of a new species within the Prevotella genus, for which we proposed the name Prevotella phocaeensis sp. nov. (Table 1). The 16S rRNA gene sequence was deposited in European Molecular Biology Laboratory–European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) under accession number LN998069. A gel view allowed us to visualize spectral differences with other Prevotella species (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Spectrum of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T obtained by MALDI-TOF MS. Spectra from 16 individual colonies were compared and reference spectrum generated. MALDI-TOF MS, matrix-assisted desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting position of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T relative to others of Prevotellaceae family. Sequences were aligned using Muscle 3.8.31 with default parameters, and phylogenetic inferences were obtained using neighbour-joining method with 500 bootstrap replicates within MEGA6 software. Only bootstraps >95% are shown. Scale bar represents 1% nucleotide sequence divergence.

Table 1.

Classification and general features of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T

| Property | Term |

|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain: Bacteria Phylum: Bacteroidetes Class: Bacteroidia Order: Bacteroidales Family: Prevotellaceae Genus: Prevotella Species: Prevotella phocaeensis Type strain: SN19T |

| Gram stain | Negative |

| Cell shape | Rod |

| Motility | Nonmotile |

| Sporulation | No |

| Temperature range | Mesophilic |

| Optimum temperature | 37°C |

| pH | 6–8.5 |

| Salinity | 0–5 g/L |

| Oxygen requirement | Strict anaerobic |

Fig. 3.

Gel view of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T relative to other Prevotella species. Gel view displays raw spectra of loaded spectrum files arranged in pseudo-gel-like look. X-axis records m/z value. Left y-axis displays running spectrum number originating from subsequent spectra loading. Peak intensity is expressed by greyscale scheme code. Colour bar and right y-axis indicating relation between colour peak is displayed; peak intensity uses arbitrary units.

Phenotypic description

Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T grew at 37°C on Colombia agar (with 5% sheep's blood) after 5 days in blood culture bottles enriched with rumen fluid (5%) and blood (5%) in anaerobic conditions. No growth occurred under aerobic conditions at 37°C and aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 28, 42 and 56°C. P. phocaeensis strain SN19T is strictly anaerobic and grows at 37°C. Bacterial cells tolerate a pH of 6 to 8.5 and an amount of NaCl of 0 to 5g/L. They were nonmotile and not sporulating at 37°C. Colonies were haemolytic, circular, small, white and irregular with a diameter of about 1 to 1.5 mm on blood-enriched Colombia agar. The Gram staining showed few Gram-negative rods (Fig. 4(A)). Bacterial cells observed under electron microscopy were sticks, ranging in length from 1.7 to 2 μm (Fig. 4(B)).

Fig. 4.

Microscopic aspects of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T. (A) Gram staining of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Transmission electron microscopy of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T using Tecnai G20 Cryo (FEI Company) transmission electron microscope operated at 200 keV. Scale bar = 500 nm.

Catalase and oxidase activities were negative for P. phocaeensis strain SN19T. Using API ZYM, positive reactions were observed for alkaline phosphatase, acid phosphatase, naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, β-glucosidase and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase. Reactions for esterase (C4), esterase lipase (C8), lipase (C14), leucine arylamidase, valine arylamidase, trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, α-galactosidase, α-glucosidase, α-fucosidase and α-mannosidase were negative. An API 50CH strip showed positive reactions for l-arabinose, d-ribose, l-xylose, d-adonitol, esculin ferric citrate, salicin, d-sucrose, d-raffinose, d-lyxose, d-tagatose, potassium 2-ketogluconate and potassium 5-ketogluconate. Negative reactions were recorded for d-xylose, d-galactose, d-fructose, l-sorbose, amygdalin, d-melibiose, d-trehalose, inulin, d-melezitose, starch, glycogen, xylitol, gentiobiose, d-fucose, l-fucose, glycerol, erythritol, d-arabinose, methyl-β-d-xylopyranoside, d-glucose, d-mannose, l-rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, d-mannitol, d-sorbitol, methyl-αd-mannopyranoside, methyl-αd-glucopyranoside, N-acetyl-glucosamine, arbutin, d-cellobiose, d-maltose, d-lactose, d-turanose, d-arabitol, l-arabitol and potassium gluconate. API20NE showed for strain SN19T a positive reaction for esculin ferric citrate and β-galactosidase but negative reactions for potassium nitrate, l-tryptophan, d-glucose (fermentation and assimilation), l-arginine, urea, gelatin, l-arabinose, d-mannose, d-mannitol, N-acetylglucosamine, d-maltose, potassium gluconate, capric acid, adipic acid, malic acid, trisodium citrate and phenylacetic acid. This bacterium is resistant to ciprofloxacin and fosfomycin but susceptible to imipenem, penicillin, teicoplanin, gentamicin, rifampicin, ceftriaxone, clindamycin, colistin, doxycycline, erythromycin, oxacillin, metronidazole and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Phenotypic characteristics of strain SN19T were compared to those of the closely related Prevotella species (Table 2). By comparison with Prevotella oralis, its phylogenetically closest neighbor, it differs in motility, l-arabinose, glucose, fructose and lactose.

Table 2.

Comparison of the different characteristics of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T with those of the closest species: Prevotella oralis ATCC 12251T, Prevotella timonensis CCUG 50105T, Prevotella micans DSM 21469T, Prevotella stercorea DSM 18206T, Prevotella marshii DSM 16973T, Prevotella saccharolytica DSM 22473T and Prevotella shahii DSM 15611T

| Property | Prevotella phocaeensis | Prevotella oralis | Prevotella timonensis | Prevotella micans | Prevotella stercorea | Prevotella marshii | Prevotella saccharolytica | Prevotella shahii |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony diameter (mm) | 1–1.5 | V | 1–2 | 1.2–1.8 | NA | 1.8–3.5 | 0.9–1.2 | 1–2 |

| Motility | Nonmotile | Nonmotile | Nonmotile | Nonmotile | Nonmotile | Nonmotile | Nonmotile | Nonmotile |

| Endospore formation | − | − | − | NA | − | NA | NA | − |

| Indole | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Major cellular fatty acidsa | C16:0, C15:0 anteiso C18:2n6 | C16:0, C18:n9c, C16:0 3-OH, anteiso-C15:0 | C14:0, C16:0, C18:2 n6,9c/C18:0 | NA | C18:1n9c, iso-C15:0, anteiso-C15:0 | C18:1 n9c, anteiso-C15:0 | C16:0, iso-C14:0, C14:0, C16:0 3-OH | C18:1 n9c, C16:0, C16:0 3-OH |

| DNA G+C content (mol%) | 44.6 | 43.1 | 42.5 | 46 | 48.2 | 51 | 44 | 44.3 |

| Production of: | ||||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase | + | NA | + | + | + | NA | + | ± |

| Catalase | − | − | − | − | − | − | NA | − |

| Oxidase | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Nitrate reductase | − | − | − | − | NA | − | − | |

| Urease | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| β-Galactosidase | + | NA | NA | + | + | NA | + | − |

| N-Acetyl-β glucosamine | + | NA | + | + | + | NA | + | + |

| Acid from: | ||||||||

| l-Arabinose | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| Ribose | + | NA | + | − | NA | − | NA | NA |

| Mannose | − | + | − | + | + | v | v | + |

| Mannitol | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Sucrose | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Glucose | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fructose | − | + | NA | + | NA | ± | + | NA |

| Maltose | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lactose | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Habitat | Human gut | Human oral cavity | Breast abscess | Human oral cavity | Human faeces | Human oral cavity | Human oral cavity | Human oral cavity |

| Study | This study | [24], [27] | [25] | [26] | [27] | [27], [28] | [29] | [30] |

+, positive result; −, negative result; ±, positive or negative reaction; v, variable result; NA, data not available.

Major cellular fatty acids listed in order of predominance.

Concerning the fatty acid methyl ester analysis by GC/MS, the major fatty acid was hexadecanoic acid (16:0, 29%). Several branched structures and specific 3-hydroxy fatty acids are also described. Cellular fatty acid profile of strain SN19T was also compared with closely related Prevotella species (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cellular fatty acid profiles (%) of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T compared to other Prevotella species

| Fatty acid | Name | Prevotella phocaeensis | Prevotella oralis | Prevotella timonensis | Prevotella stercorea | Prevotella marshii | Prevotella shahii |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated straight chain | |||||||

| 14:0 | Tetradecanoic acid | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 2.1 | 19.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 10.9 |

| 15:0 | Pentadecanoic acid | tr | tr | NA | tr | 5.9 | 1.0 |

| 16:0 | Hexadecanoic acid | 28.7 ± 1.4 | 19.2 | 15.3 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 16.9 |

| 17:0 | Heptadecanoic acid | tr | tr | NA | NA | tr | NA |

| 18:0 | Octadecanoic acid | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 | 16 | 0.8 | tr | 2.8 |

| Unsaturated straight chain | |||||||

| 16:1n5 | 11-Hexadecenoic acid | tr | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 16:1n7 | 9-Hexadecenoic acid | tr | NA | NA | 1.8 | 1.4 | NA |

| 18:2n6 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid | 15.1 ± 0.5 | NA | 16 | 2.2 | 0.6 | NA |

| 18:1n6 | 12-Octadecenoic acid | 1.0 ± 0.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 18:1n9 | 9-Octadecenoic acid | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 18.6 | NA | 14.7 | 10.2 | 18.7 |

| 20:4n6 | 5,8,11,14-Eicosatetraenoic acid | tr | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hydroxy acids | |||||||

| 15:0 3-OH | 3-hydroxy-Pentadecanoic acid | tr | NA | NA | 2.4 | 1.0 | NA |

| 16:0 3-OH | 3-hydroxy-Hexadecanoic acid | 9.7 ± 0.3 | 10.4 | NA | 1.0 | 1.2 | 16.3 |

| 17:0 3-OH iso | 3-hydroxy-15-methyl-Hexadecanoic acid | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 4.9 | NA | 6.4 | 9.3 | 1.3 |

| 17:0 3-OH anteiso | 3-hydroxy-14-methyl-Hexadecanoic acid | tr | NA | NA | 1.9 | 1.7 | NA |

| Saturated branched chain | |||||||

| 5:0 anteiso | 2-methyl-Butanoic acid | tr | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 14:0 iso | 12-methyl-Tridecanoic acid | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 3.0 | 14 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 4.4 |

| 15:0 iso | 13-methyl-Tetradecanoic acid | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 3.2 | NA | 23.7 | 8.7 | 3.4 |

| 15:0 anteiso | 12-methyl-Tetradecanoic acid | 19.1 ± 0.6 | 20.6 | NA | 26.2 | 40.1 | 6.8 |

| 16:0 iso | 14-methyl-Pentadecanoic acid | tr | 1.7 | NA | 2.7 | 1.7 | 1.0 |

| 17:0 iso | 15-methyl-Hexadecanoic acid | tr | tr | NA | 1.7 | tr | NA |

| 17:0 anteiso | 14-methyl-Hexadecanoic acid | tr | 1.5 | NA | 1.3 | 2.6 | NA |

| Study | This study | [27] | [25] | [27] | [28] | [30] | |

NA, data not available; tr, trace amounts <1%.

Prevotella saccharolytica and micans were not listed because their complete fatty acid profiles were not available.

Genomic characterization and comparison

Genome properties

The genome is 2 922 117 bp long with 44.6% of G+C content (Fig. 5). It is composed of 12 scaffolds (composed of 13 contigs). Of the 2486 predicted genes, 2430 were protein-coding genes and 56 were RNAs (three genes are 5S rRNA, one gene is 16S rRNA, three genes are 23S rRNA and 49 genes are tRNA genes). A total of 1403 genes (57.74%) were distributed in putative function (by COGs or by NR BLAST). Twelve genes were identified as ORFans (0.49%). The remainder of the genes were annotated as hypothetical proteins (971 genes, 39.96%). Table 4 summarizes the properties and the statistics of the genome and Table 5 the distribution of predicted genes of strain SN19T according to COGs categories. The genome sequence was deposited in EMBL-EBI under accession number FIZG00000000.

Fig. 5.

Graphical circular map of Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T genome. From outside to centre: contigs (red/grey), genes on forward strand coloured by COGs categories (only genes assigned to COGs), genes on reverse strand coloured by COGs categories (only gene assigned to COGs), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red), GC content and GC skew. COGs, Clusters of Orthologous Groups database.

Table 4.

Nucleotide content and gene count levels of genome

| Attribute | Genome (total) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Value | % of totala | |

| Size (bp) | 2 922 117 | 100 |

| G+C content (%) | 1 303 042 | 44.60 |

| Coding region (bp) | 2 592 985 | 88.74 |

| Total genes | 2486 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 56 | 2.25 |

| Protein-coding genes | 2430 | 100 |

| Genes with function prediction | 161 | 6.63 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1286 | 52.92 |

| Genes with peptide signals | 667 | 27.45 |

| Gene associated with resistance genes | 0 | 0.00 |

| Gene associated with bacteriocin genes | 7 | 0.29 |

| Gene associated with mobilome | 670 | 27.57 |

| Gene associated with toxin/antitoxin | 30 | 1.56 |

| Protein associated with ORFan | 12 | 0.49 |

| Genes associated with PKS or NRPS | 7 | 0.29 |

COGs, Clusters of Orthologous Groups database; NRPS, nonribosomal peptide synthase, PKS, polyketide synthase.

Total is based on either size of genome in base pairs or total number of protein-coding genes in annotated genome.

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with 25 general COGs functional categories

| Code | Value | % of totala | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 162 | 6.67 | Translation |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 78 | 3.21 | Transcription |

| L | 96 | 3.95 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 20 | 0.82 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 45 | 1.85 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 39 | 1.60 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 125 | 5.14 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 11 | 0.45 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 19 | 0.78 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 70 | 2.884 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| X | 15 | 0.62 | Mobilome: prophages, transposons |

| C | 82 | 3.37 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 109 | 4.49 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 101 | 4.16 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 58 | 2.39 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 89 | 3.66 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 56 | 2.30 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 75 | 3.09 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 14 | 0.58 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 95 | 3.91 | General function prediction only |

| S | 44 | 1.81 | Function unknown |

| — | 1144 | 47.08 | Not in COGs |

Total is based on total number of protein-coding genes in annotated genome.

Genome comparison with other Prevotella species

The draft genome sequence of strain SN19T is smaller than that of Prevotella saccharolytica, Prevotella loescheii, Prevotella timonensis, Prevotella stercorea and Prevotella shahii (2922, 2976, 3509, 3156, 3097 and 3490 MB respectively), but larger than that of Prevotella oralis, Prevotella oulorum, Prevotella marshii and Prevotella micans (2840, 2806, 2559 and 2427 MB respectively). The G+C content of strain SN19T is smaller than that of P. loescheii, P. oulorum, P. stercorea, P. marshii and P. micans (44.60, 46.62, 46.78, 49.00, 47.46 and 45.49% respectively), but larger than that of P. oralis, P. saccharolytica, P. timonensis and P. shahii (44.54, 43.30, 42.38, and 44.38% respectively). The gene content of strain SN19T is smaller than that of P. oralis, P. saccharolytica, P. loescheii, P. timonensis, P. oulorum, P. stercorea and P. shahii (2430, 2488, 2762, 2838, 2770, 2488, 3017 and 3392 respectively), but larger than that of P. marshii and P. micans (2335 and 2329 respectively).

Furthermore, strain SN19T shares 1054, 1241, 1317, 1209, 1662, 1404, 1269, 1254 and 1236 orthologous genes with P. micans, P. stercorea, P. timonensis, P. shahii, P. oralis, P. loescheii, P. saccharolytica, P. oulorum and P. marshii respectively (Table 6). AGIOS values vary from 56.79% between P. saccharolytica and P. stercorea, to 80.98 between P. loescheii and P. shahii among compared genomes except for strain SN19T. When this one was compared with other species within the Prevotella genus, values ranged from 58.13 with P. stercorea to 76.50 with P. oralis, thus confirming its new species status (Table 6). Table 7 shows the pairwise comparison of strain SN19T with other Prevotella species using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator. Fig. 6 shows the distribution of functional classes of predicted genes on the chromosomes of strain SN19T and related species of Prevotella genus according to the COGs of proteins. It demonstrates that the distribution of genes into COGs categories is similar in all compared Prevotella species.

Table 6.

Numbers of orthologous proteins shared between genomes (upper right)a

| Prevotella micans | Prevotella stercorea | Prevotella timonensis | Prevotella shahii | Prevotella oralis | Prevotella loescheii | Prevotella saccharolytic | Prevotella oulorum | Prevotella marshii | Prevotella phocaeensis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. micans | 2329 | 970 | 988 | 957 | 1054 | 1094 | 969 | 988 | 1037 | 1054 |

| P. stercorea | 56.89 | 3017 | 1187 | 1053 | 1240 | 1227 | 1064 | 1112 | 1122 | 1241 |

| P. timonensis | 65.64 | 57.46 | 2770 | 1133 | 1319 | 1316 | 1131 | 1190 | 1188 | 1317 |

| P. shahii | 64.85 | 57.52 | 67.04 | 3392 | 1206 | 1381 | 1135 | 1122 | 1121 | 1209 |

| P. oralis | 59.20 | 57.41 | 60.63 | 59.71 | 2488 | 1398 | 1276 | 1257 | 1230 | 1662 |

| P. loescheii | 65.65 | 58.40 | 67.18 | 80.98 | 59.93 | 2838 | 1335 | 1292 | 1279 | 1404 |

| P. saccharolytica | 65.58 | 56.79 | 67.46 | 70.10 | 60.40 | 71.07 | 2762 | 1143 | 1139 | 1269 |

| P. oulorum | 57.71 | 58.87 | 58.71 | 58.51 | 58.41 | 58.56 | 58.36 | 2488 | 1167 | 1254 |

| P. marshii | 57.69 | 58.05 | 58.69 | 58.19 | 59.36 | 58.61 | 58.34 | 58.29 | 2335 | 1236 |

| P. phocaeensis | 66.26 | 58.13 | 68.90 | 67.22 | 76.50 | 67.83 | 68.37 | 58.77 | 59.08 | 2430 |

Average percentage similarity of nucleotides corresponding to orthologous proteins shared between genomes (lower left) and numbers of proteins per genome (bold).

Table 7.

Pairwise comparison of Prevotella phocaeensis with other species using GGDC, formula 2 (DDH estimates based on identities/HSP length),a upper right, for: (1) Prevotella phocaeensis strain SN19T, (2) Prevotella oralis strain ATCC 33269, (3) Prevotella micans strain F0438, (4) Prevotella stercorea strain CB35, (5) Prevotella timonensis strain 4401737, (6) Prevotella shahii strain EHS11, (7) Prevotella loescheii strain ATCC 15930, (8) Prevotella saccharolytica strain JCM 17484, (9) Prevotella oulorum strain F0390 and (10) Prevotella marshii strain JCM 13450

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100% | 77.20 ± 2.7 | 31.50 ± 2.4 | 20.80 ± 2.2 | 22.20 ± 2.3 | 20.50 ± 2.2 | 20.10 ± 2.2 | 22.60 ± 2.3 | 20.10 ± 2.5 | 23.70 ± 2.3 |

| 2 | 100% | 22.10 ± 2.3 | 20.50 ± 2.2 | 21.00 ± 2.3 | 20.20 ± 2.3 | 19.70 ± 2.2 | 20.90 ± 2.3 | 20.10 ± 2.2 | 20.90 ± 2.3 | |

| 3 | 100% | 21.60 ± 2.2 | 25.30 ± 2.3 | 21.20 ± 2.3 | 24.20 ± 2.3 | 25.30 ± 2.4 | 24.60 ± 2.3 | 35.20 ± 2.4 | ||

| 4 | 100% | 30.80 ± 2.4 | 21.50 ± 2.3 | 20.20 ± 2.2 | 19.70 ± 2.2 | 23.50 ± 2.3 | 24.00 ± 2.3 | |||

| 5 | 100% | 25.70 ± 2.3 | 24.10 ± 2.3 | 20.00 ± 2.2 | 26.40 ± 2.3 | 26.10 ± 2.4 | ||||

| 6 | 100% | 24.90 ± 2.3 | 22.70 ± 2.3 | 22.60 ± 2.3 | 27.90 ± 2.4 | |||||

| 7 | 100% | 28.30 ± 2.4 | 25.60 ± 2.4 | 25.10 ± 2.3 | ||||||

| 8 | 100% | 23.50 ± 2.3 | 25.60 ± 2.3 | |||||||

| 9 | 100% | 25.30 ± 2.4 | ||||||||

| 10 | 100% |

DDH, DNA-DNA hybridization; GGDC, Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator; HSP, high-scoring segment pairs.

Confidence intervals indicate inherent uncertainty in estimating DDH values from intergenomic distances based on models derived from empirical test data sets (which are always limited in size). These results are in accordance with 16S rRNA and phylogenomic analyses as well as GGDC results.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of functional classes of predicted genes of strain SN19T and related species of Prevotella genus according to COGs of proteins. COGs, Clusters of Orthologous Groups database.

Discussion and Conclusion

Strain SN19T was isolated from the stool sample of an 81-year-old white woman who was a patient at La Timone Hospital diagnosed with C. difficile colitis with good outcome without faecal microbiota transplantation. On the basis of phenotypic, genomic and phylogenetic characteristics, we have isolated a new species, strain SN19T, within the genus Prevotella, whose closest species is Prevotella oralis. These results and the divergence of the 16s rRNA gene sequence with the closest species confirms that SN19T strain is a new species. Also, genomic analysis identified 12 ORFans (Table 4) and at least 768 (31.6%) of 2430 orthologous proteins genes not shared with the closest phylogenetic neighbor, Prevotella oralis (Table 6), supporting the description of a new species. Strain SN19T differs from the phylogenetically closest species by its mobility, its major fatty acids and its inability to use certain sugars including mannose, glucose, fructose, maltose and lactose (Table 2), suggesting that they are different species.

The composition of the intestinal microbiota shows an abundance of bacteria belonging to Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla. In Bacteroidetes, there is a predominance of Bacteroides and Prevotella. Prevotella are more prevalent in populations with plant-based diet, suggesting that it contributes to their catabolism in the human gut. Possibly as a result of its link to a vegetarian diet, Prevotella is found less often in the Western population; Prevotella species in this population are mostly found in the oral cavity [31], [32]. Moreover, Arumugam et al. [33] reported the existence of enterotypes in the human microbiome including Prevotella as a main contributor of one of these enterotype regardless of age, sex or origin. The enterotype Prevotella varies greatly in number of species and functional composition.

In addition, the abundance of Prevotella in a body habitat is correlated by an improvement in glucose metabolism [34]. However, the presence of Prevotella in the human gut was also linked to inflammation [35]. Further studies are needed in order to decipher the role of Prevotella phocaeensis in health and diseases and particularly plant catabolism, glucose regulation and its interaction with Clostridium difficile in the human gut. Some cases of Clostridium difficile infection were treated by transplantation of faecal microbiota [36]. Maybe the presence of P. phocaeensis, a probable member of the human mature anaerobic gut microbiota [6], explains the good outcome of the patient with Clostridium difficile infection.

Therefore, considering phenotypic differences with the closest species, the proteomic profile obtained with MALDI-TOF MS of strain SN19T, its phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence, its genomic description and annotation, AGIOS and digital DDH values, we propose the creation of strain SN19T as a new species named Prevotella phocaeensis sp. nov. (= CSUR P2259 = DSM 103364). Finally, we showed here that culturomics and taxonogenomics dramatically extend the discovery of human mature anaerobic gut microbiota previously associated with gut maturation and health [6].

Description of Prevotella phocaeensis sp. nov.

Prevotella phocaeensis (pho.cae.en′sis, L. fem. adj. phocaeensis, ‘of Phocaea,’ the Latin name of Marseille, adapted from the first Greek name of Marseille, Phokaia, where the strain was isolated). Strict anaerobic, Gram-negative, oxidase and catalase negative, not endospore forming, and with nonmotile rods, the colonies are haemolytic, circular, small and white, and have a diameter of about 1 to 1.5 mm on Columbia agar + 5% sheep's blood. Strain SN19T grows at 37°C after 72 hours of incubation and tolerates a pH of 6 to 8.5 and an amount of NaCl of 0 to 5 g/L. Bacterial cells observed under electron microscopy were sticks ranging in length from 1.7 to 2 μm, with a diameter lower to 0.5 μm. Using the ZYM strip and API 50CH, positive reactions were observed for alkaline phosphatase, acid phosphatase, naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase, β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, β-glucosidase, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase and l-arabinose, d-ribose, l-xylose, d-adonitol, esculin ferric citrate, salicin, d-sucrose, d-raffinose, d-lyxose, d-tagatose, potassium 2-ketogluconate and potassium 5-ketogluconate. API20NE shows a positive reaction for esculin ferric citrate and β-galactosidase. P. phocaeensis strain SN19T was susceptible to imipenem, penicillin, teicoplanin, gentamicin, rifampicin, ceftriaxone, clindamycin, colistin, doxycycline, erythromycin, oxacillin, metronidazole and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Hexadecanoic acid (16:0–29%) is the predominant fatty acid. The G+C content of the genome is 44.6%. The accession numbers of the sequences of 16S rRNA and genome which were deposited in EMBL-EBI are LN998069 and FIZG00000000, respectively. The habitat of the organism is the human gut microbiota. The type strain SN19T (= CSUR P2259 = DSM 103364) was isolated from the stool sample of an 81-year-old white woman.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Xegen Company (www.xegen.fr/) for automating the genomic annotation process. This study was funded by the Fondation Méditerranée Infection. The authors thank M. Lardière for English-language review.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Landman C., Quévrain E. Le microbiote intestinal: description, rôle et implications physiopathologiques. Rev Med Interne. 2016;37:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooper L.V. Bacterial contributions to mammalian gut development. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christl S.U., Murgatroyd P.R., Gibson G.R., Cummings J.H. Production, metabolism, and excretion of hydrogen in the large intestine. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1269–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turnbaugh P.J., Ley R.E., Mahowald M.A., Magrini V., Mardis E.R., Gordon J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L., Christophersen C.T., Sorich M.J., Gerber J.P., Angley M.T., Conlon M.A. Low relative abundances of the mucolytic bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila and Bifidobacterium spp. in feces of children with autism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:6718–6721. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05212-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Million M., Diallo A., Raoult D. Gut microbiota and malnutrition. Microb Pathog. 2016 Feb 4 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.003. pii: S0882-4010(15)30212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagier J.C., Armougom F., Million M., Hugon P., Pagnier I., Robert C. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:1185–1193. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seng P., Drancourt M., Gouriet F., La Scola B., Fournier P.E., Rolain J.M. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:543–551. doi: 10.1086/600885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morel A.S., Dubourg G., Prudent E., Edouard S., Gouriet F., Casalta J.P. Complementarity between targeted real-time specific PCR and conventional broad-range 16S rDNA PCR in the syndrome-driven diagnosis of infectious diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:561–570. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2263-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stackebrandt E., Ebers J. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today. 2006;33:152. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasser M. Microbial ID; Newark, NY: 2006. Bacterial identification by gas chromatographic analysis of fatty acids methyl esters (GC-FAME) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dione N., Sankar S.A., Lagier J.C., Khelaifia S., Michele C., Armstrong N. Genome sequence and description of Anaerosalibacter massiliensis sp. nov. New Microb New Infect. 2016;10:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyatt D., Chen G.L., Locascio P.F., Land M.L., Larimer F.W., Hauser L.J. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119–130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe T.M., Eddy S.R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagesen K., Hallin P., Rodland E.A., Staerfeldt H.H., Rognes T., Ussery D.W. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Käll L., Krogh A., Sonnhammer E.L. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gouret P., Thompson J.D., Pontarotti P. PhyloPattern: regular expressions to identify complex patterns in phylogenetic trees. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:298. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lechner M., Findeiss S., Steiner L., Marz M., Stadler P.F., Prohaska S.J. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramasamy D., Mishra A.K., Lagier J.C., Padhmanabhan R., Rossi M., Sentausa E. A polyphasic strategy incorporating genomic data for the taxonomic description of new bacterial species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:384–391. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.057091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auch A.F., von Jan M., Klenk H.P., Göker M. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2:117–134. doi: 10.4056/sigs.531120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meier-Kolthoff J.P., Auch A.F., Klenk H.P., Göker M. Genome sequence–based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gouret P., Paganini J., Dainat J., Louati D., Darbo E., Pontarotti P. Integration of evolutionary biology concepts for functional annotation and automation of complex research in evolution: the multi-agent software system DAGOBAH. In: Pontarotti P., editor. Evolutionary biology—concepts, biodiversity, macroevolution and genome evolution. Springer; Berlin: 2011. pp. 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouret P., Vitiello V., Balandraud N., Gilles A., Pontarotti P., Danchin E.G. Figenix: intelligent automation of genomic annotation: expertise integration in a new software platform. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loesche W.J., Socransky S.S., Gibbons R.J. Bacteroides oralis, proposed new species isolated from the oral cavity of man. J Bacteriol. 1964;88:1329–1337. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.5.1329-1337.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glazunova O.O., Launay T., Raoult D., Roux V. Prevotella timonensis sp. nov., isolated from a human breast abscess. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:883–886. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downes J., Liu M., Kononen E., Wade W.G. Prevotella micans sp. nov., isolated from the human oral cavity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:771–774. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.002337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi H., Shibata K., Mitsuo Sakamoto M., Tomita S., Benno Y. Prevotella copri sp. nov. and Prevotella stercorea sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:941–946. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64778-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downes J., Sutcliffe I., Tanner A.C.R., Wade W.G. Prevotella marshii sp. nov. and Prevotella baroniae sp. nov., isolated from the human oral cavity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1551–1555. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Downes J., Tanner A.C., Dewhirst F.E., Wade W.G. Prevotella saccharolytica sp. nov., isolated from the human oral cavity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:2458–2461. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.014720-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakamoto M., Suzuki M., Huang Y., Umeda M., Ishikawa I., Benno Y. Prevotella shahii sp. nov. and Prevotella salivae sp. nov., isolated from the human oral cavity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:877–883. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ley R.E. Gut microbiota in 2015: Prevotella in the gut: choose carefully. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:69–70. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu G.D., Chen J., Hoffmann C., Bittinger K., Chen Y.Y., Keilbaugh S.A. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arumugam M., Raes J., Pelletier E., Le Paslier D., Yamada T., Mende D.R. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovatcheva-Datchary P., Nilsson A., Akrami R., Lee Y.S., De Vadder F., Arora T. Dietary fiber–induced improvement in glucose metabolism is associated with increased abundance of Prevotella. Cell Metab. 2015;22:971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scher J.U., Sczesnak A., Longman R.S., Segata N., Ubeda C., Bielski C. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. ELife. 2013;2:e01202. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shankar V., Hamilton M.J., Khoruts A., Kilburn A., Unno T., Paliy O. Species and genus level resolution analysis of gut microbiota in Clostridium difficile patients following fecal microbiota transplantation. Microbiome. 2014;2:13. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]