Abstract

We study the dynamic network of e-mail traffic and find that it develops self-organized coherent structures similar to those appearing in many nonlinear dynamic systems. Such structures are uncovered by a general information theoretic approach to dynamic networks based on the analysis of synchronization among trios of users. In the e-mail network, coherent structures arise from temporal correlations when users act in a synchronized manner. These temporally linked structures turn out to be functional, goal-oriented aggregates that must react in real time to changing objectives and challenges (e.g., committees at a university). In contrast, static structures turn out to be related to organizational units (e.g., departments).

An intriguing aspect of networks is the appearance of internal structures whose origins cannot be explained by using graph theoretic concepts alone. These are contextual and thematic groups that form by the clustering of nodes with similar properties. Their existence can be detected by various measures of connectivity (1-3), and they have numerous uses in data mining (4). The addition of temporal dynamics can be expected to have a profound effect on the creation of such structures. The time-dependent activation of links creates a flow of information along the static network that, in turn, defines an ever-changing subgraph that can only exist as a consequence of this flow. This flux of activation will concentrate and cluster into structures that act coherently for a given period, then relax and decay until they are excited again.

A dynamic network can be defined as a graph whose links are turned on or off by the individual nodes. Prominent examples are the brain, where spikes are exchanged among neurons to create thoughts, and communication networks such as telephones or e-mail. It is convenient to think of the static counterpart as the same graph in which permanent links are made when certain criteria are fulfilled, e.g., when the number of messages transmitted between two nodes exceeds a certain threshold level. The temporal dynamics create coherent space-time structures that involve correlations of the interacting nodes. These (coherent and dynamic) structures will in general be very different from the fixed ones that appear in the static network.

E-mail traffic, a fascinating form of communication that increasingly dominates written correspondence, creates such a dynamic network. The resulting graph has intricate structures that are neither apparent to the users nor carried by the content of the messages. The traffic has a precise time stamp on every interaction, which can be used as a “stroboscopic probe” to identify the coherent space-time structures that arise. In this work, we measure synchronized interaction among users by looking at communicating triangles of users. We analyze them with the tools of information theory (5) and find a form of organization that differs from that which can be captured by static attributes of the graph such as curvature. A similar approach is often used to find correlations and synchronization of spike trains in the neural code (6), evoking an analogy between the internal e-mail communication in a university and neuronal activity in the brain.

The Experiment

Our data were extracted from the log files of one of the main mail servers at one of our universities and consist of >2 × 106 e-mail messages sent during a period of 83 days and connecting ≈10,000 users. The content of the messages was, of course, never accessible, and the only data taken from the log files were the “to,” “from,” and “time” fields. The data were first reduced to the internal mail within the institution, because external links were necessarily incomplete. Once aliases were resolved, we were left with a set of 3,188 users interchanging 309,125 messages.

A directed static graph was then constructed by designating users as nodes and connecting any two of them with a directed link when an e-mail message had gone between them during the 83 days. Statistical properties of the degree of this graph have been reported before (7).¶ Connectivity of this static graph will reveal structures within the organization (7-9). We have previously shown (1) that a powerful tool for identifying such structural organization is the number of triangles T (triplets in which all pairs communicate) in which a node of degree v (total number of partners) participates, normalized by the number of triangles v(v - 1)/2 to which it could potentially belong. This defines the clustering coefficient c = 2T/(v2 - v) (10-13), which, as we showed (1), induces a curvature on the graph.

One marked difference between the graphs of e-mail and of the World Wide Web (WWW) should be noted at this point. In the WWW, the central organizing role of “hubs” (nodes with many outgoing links) that confer importance to “authorities” (nodes with many ingoing links) has been noted (14) and used very successfully (e.g., by Google). The contribution of authorities and hubs is, however, not to the creation of communities and interest groups. This is evident because the high degree of both hubs and authorities tends to reduce their curvature considerably. High-curvature nodes, in contrast, are usually the specialists of their community and are highly connected in bidirectional links to others in the group. In the e-mail graph, hubs tend to be machines, mass mailers, or users that transfer general messages (e.g., seminar notifications) going to many users, whereas authorities are more like service desks. Thus, the importance of hubs and authorities is small when we consider the core use of the e-mail structure as dealing with thematic rather than organizational issues. Hubs and authorities do, however, play a role in such questions as diffusion of viruses or, more generally, how many people are being reached (7). However, most mass mailings do not solicit an answer and therefore do not contribute to interaction (“dialogue”) as we define and study it here. In our analysis we discarded mass mailings (>18 recipients) altogether. There remained 202,695 links.

The different manner in which triangles and transitivity interplay in the World Wide Web (WWW) and in the e-mail graphs is also illuminating. Although it involves three nodes, the notion of curvature in the WWW is mainly a local one, based on the more basic concept of a “colink.” This is a link between two nodes that point to each other, establishing a “friendly” connection based on mutual recognition. Building from the single pair, the fundamental unit of connectivity is the triangle. In the WWW, transitivity is natural, and we have shown previously (1) that if node A is friendly with nodes B and C, it is often correct to assume that B and C are friends. On the contrary, e-mailing is so prolific that A's dialogue with B and with C usually does not imply that B and C carry out a dialogue, and, even if they do, then the three communications determining the edges of the triangle could be independent; as a consequence, transitivity breaks down. We will see that static structures (such as departments) emerge as having high curvature, whereas dialogue among members of a group implies a more functional, and perhaps goal-oriented, structure, where timing is crucial.

The static analysis expands the notion of a mutual link, or colink, to the e-mail network by designating a link between nodes A and B only if A had sent a message to B and B had sent a message back during the whole period under investigation. We found 7,087 such pairs, sending 105,349 messages to each other, among 20,879 directed pairs who sent perhaps mail just one way (and of the 3,188 × 3,187/2 possible connections in the graph). The 7,087 pairs formed a total of 6,378 triangles.

The Model

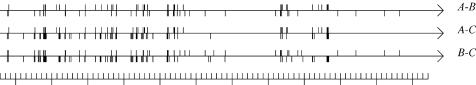

To analyze the behavior of this reduced network, we viewed any pair of “conversing” users as exchanging signals on a transmission line via which information can be propagated in both directions. We completely disregarded the fact that there is internal information in the messages, discarding even information that is in principle available in the log files such as the size of the messages. The data for each pair composed a spike train whose horizontal axis is time, with upward ticks for mail sent A→B and downward ticks for mail sent B→A (some samples are shown in Fig. 1). We now define that A and B conduct a dialogue on a given day if A sends mail on that day to B and B answers on the same day, or vice versa.

Fig. 1.

Spike trains for the three communication channels determining the edges of a triangle formed by users A, B, and C. We have Ip(A,B) = 0.095, Ip(A,C) = 0.394, Ip(B,C) = 0.172, and IT = 1.606. It is important to note that Ip and IT capture the synchronization of the e-mail exchange at two different levels. IT measures the coherence of the triangle as a whole and can take on high values, even though some of the Ip values are relatively small. The horizontal line at the bottom represents the whole period under analysis divided into days (and weekends) and was introduced to aid the visualization of the events determining the probabilities entering Ip and IT (see Eqs. 1 and 2).

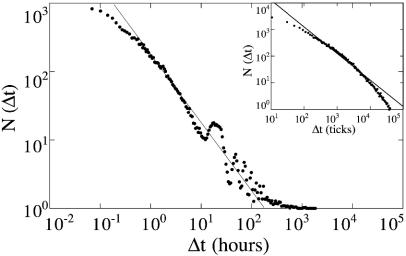

The temporal dynamics of the e-mail network immediately reveals new statistical properties, shown in Fig. 2. We define Δt as the time delay between a message going from A→B and a response going from B→A. Although no clear power law is evident in Fig. 2, the behavior can be approximated by P(Δt) ≈ Δt-1. The appearance of a peak ranging from Δt = 16 hours to Δt = 24 hours can be explained by sociological behavior involving the time (usually 16 hours) between when people leave work and when they return to their offices. This (already weak) peak disappears when considering (Fig. 2 Inset) a “tick” of the system (i.e., a message sent) as the basic time unit. We suspect that the approximate power law is caused by random communications between two users, whereas the flat incipient part implies actual correlation between two users (when the answer comes before 10 hours have passed, i.e., on the same day).

Fig. 2.

Probability distribution of the response time until a message is answered (as described in The Model). (Inset) The same probability distribution is measured in “ticks,” i.e., units of messages sent in the system. Binning is logarithmic. Solid lines approximately follow Δt-1 and are meant as guides for the eye.

Choosing the basic tick of the clock (the sending of a message in the network) as a variable time unit smoothens many features (as in Fig. 2 Inset). In particular, the slowing down of the network over nights and weekends is eliminated. However, the mathematics of correlation becomes much more involved, and we have also checked that the interaction is very well captured by sticking to the more intuitive notion of “same day.” In light of these considerations, we choose 24 hours as the natural time unit within which B must answer. In principle, some multiple of this unit could serve as well, but the results shown in Fig. 2 indicate that most interactions take place within 10 hours. We further found that extending the time unit to include responses sent the next day gave similar results.

The mathematical description of the experiment proceeds through two steps (compare Fig. 1). First, on a more local level, we consider a pair of communicating users that we shall denote by A and B. We introduce the empirical probabilities pA(i) and pB(i), where i = 0,1. The value 1 corresponds to the event that at least one e-mail has been sent to the partner on a given day, whereas the value 0 corresponds to the event that no e-mail has been sent on that day. The measured values of these probabilities are given by

|

1 |

where NA(i) is the number of days for which the event i occurred for A, NB(i) is defined similarly for B, and d is the total number of days (d = 83). We then characterize the joint activity of A and B by considering the probabilities pAB(i, j), defined as

|

2 |

where NAB is the number of days where A was in state i and B was in state j (i.e., sending mail to the partner or not) and i, j ∈ {0, 1}. It is now possible to determine to what extent the activity of A influences the activity of B by means of the mutual information Ip(A, B) (the subscript p stands for “pair”):

|

3 |

Ip measures in what way knowing what A does will predict what B does and vice versa [note that Ip(A, B) = Ip(B, A)].

The next step consists in considering every triangle of communicating users; to be specific, we designate them by A, B, and C. To capture their joint activity we introduce the probabilities pABC(i1, i2; i3, i4; i5, i6) = pABC(i), where i1,..., i6 ∈ {0, 1}. The pair (i1, i2) refers to the communication A ↔ B, (i3, i4) to A ↔ C, and (i5, i6) to B ↔ C. For example, the pair (i1 = 1, i2 = 0) must be interpreted as the occurrence when on a given day A sends mail to B, but B does not send mail to A. An equivalent interpretation holds for all other pairs. The above probabilities read pABC(i) = NABC(i)/d, where NABC(i) is the number of days on which the pattern (event) i occurred.

We now define the temporal coherence of a triangle as the degree of synchronization among the activity of the three users. This is achieved by looking at a form of the mutual information (Kullback-Leibler divergence) IT(A, B, C) (in this case the subscript T stands for “triangle”), defined as

|

4 |

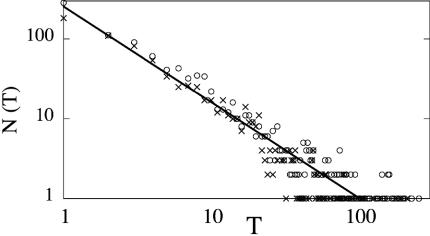

One readily sees that the temporal coherence IT(A, B, C) is invariant under any permutation of A, B, and C. Note that IT ≤ log 16, and the maximum is attained when the four possible patterns for each edge are equiprobable and fully correlated (see also ref. 16). More insight into Ip and IT can be gained by looking at Fig. 1, which shows the three communications determining a triangle. A statistical quantity of interest (Fig. 3) is the number of triangles T in which a user participates. The distribution of both the static and the dynamic (temporal coherence of ≥0.1) triangles follows a power law over two decades, with exponent -1.2.

Fig. 3.

Graph of static and temporal statistical quantities. Probability distribution of the number of triangles T in which a user participates. Circles indicate static triangles, whereas crosses indicate temporally coherent triangles (i.e., mutual information IT ≥ 0.1). Both lines are well fitby N ≈ T-1.2, and the black line is provided as a guide for the eye with this slope.

With the help of the temporal coherence IT, it is possible to replace the static transitivity by a notion of temporal transitivity. The assumption is that when the e-mail exchange in a triangle is highly synchronized, the three users are indeed involved in a common dialogue (or “trialogue”). This transitive relationship among users can be extended naturally to adjacent triangles. This idea relies on the observation that in the presence of two highly synchronized triangles with a common edge, the four users are supposed to influence each other's activity. In this way it is possible to extract groups of users carrying out a conversation. We thus constructed a conjugate graph where we first drew a node for each triangle for which IT was larger than a given cutoff. Two of these nodes were connected by a link when the corresponding triangles had a common edge, that is, when four people A, B, C, and D were involved in these two triangles (e.g., A, B, and C and B, C, and D). Our construction offers a perspective on the appearance of circles of users sharing a common interest, defining thematic groups.

Discussion

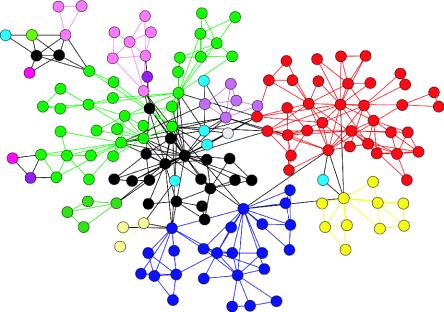

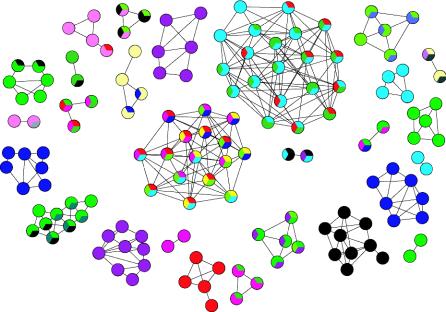

For the purpose of comparison, we first consider the static graph resulting from the e-mail network we analyzed (Fig. 4). For the sake of clarity, only nodes, i.e., users, with a curvature of >0.1 are present; in addition, every pair of users must have exchanged at least 10 e-mails. The temporal dynamics intrinsic to the e-mail exchange is here neglected, and triangles represent a sign of static transitive recognition, carrying no information about temporal coherence between the individual communications. In this case we see the clear appearance of departmental communities. Our findings on the organizational aspects of e-mail traffic are thus in agreement with the findings of Tyler et al. (9) but are based here on the quantitative concept of curvature.

Fig. 4.

The static structure of the graph of e-mail traffic obtained from our data, arranged according to curvature, based on triangles of mutual recognition. Time is thus not taken into account, and the graph of users arranges itself primarily according to departments, shown in various colors.

Fig. 5, on the other hand, shows the conjugate graph associated with a cutoff of IT ≥ 0.5 but without a cutoff on curvature; again we only considered pairs that exchanged at least 10 e-mails. The threshold is related to the fact that there is an a priori probability for a nonzero IT. This value can be estimated based on Bayesian statistics, but such an estimation would necessitate some detailed assumptions on what is probable behavior for people sending e-mails. For example, a uniform measure in the space of probabilities leads to a critical value of IT = 0.7531. Fig. 6 demonstrates a transition in the cumulative probability in our data, at a value of IT ≈ 0.65. In practice, we empirically set the threshold at IT = 0.5, which gave a useful representation of the dynamic groups.

Fig. 5.

The conjugate graph, for a cutoff of 0.5. Each node is a triangle of three people conferring with temporal coherence IT ≥ 0.5 (rather than a single user, as in Fig. 4), and each link connects two adjacent such triangles. The three colors of each node indicate the departments of the three people composing that node (we used the same color code as in Fig. 4). Note the strong clustering of the graph into very compact groups of people. The users cross departmental boundaries (their interests and connections are not shown, in consideration of privacy).

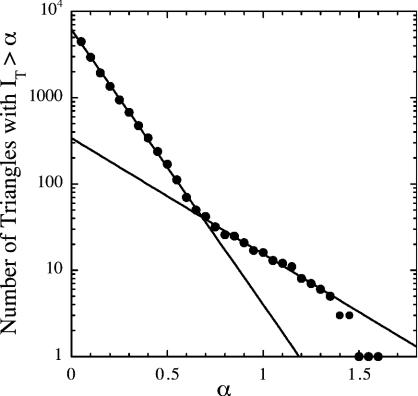

Fig. 6.

Cumulative probability graph for IT. The solid lines are fits to two different exponentials, and they cross at the critical point of IT ≈ 0.65. Axes are semilogarithmic. α is the threshold value.

We recognize in Fig. 5 several highly connected, totally separated clusters, indicating different thematic groups. Some of the clusters identified in Fig. 4 survive and are lifted in part to the graph of temporal dynamics (Fig. 5), indicating that within some departments there are dialogues; furthermore, some departments split into different interest groups. However, we find many clusters that are new and do not appear in the high-curvature graph (Fig. 4). These clusters typically comprise users who are not in the same department (as shown by the multiple colors of the disks in Fig. 5). Very few users appear in more than one cluster so that the spreading of functional information is restricted within the thematic communities, in contrast to the spreading of computer viruses, for example, which propagate easily through the entire graph (7).

The creation of coherent structures in flow patterns is well known from hydrodynamics, where vortices, plumes, and other localized structures play an important role in determining features of fluid flow (15). In the case of dynamic networks, we have shown that the flow of information along the edges of a graph creates a type of coherent structure. This localized structure encompasses a number of users that act in synchrony.

We may obtain further insight on the difference between the dynamic and the static groups by considering directly the activity and time sequence of events in the groups. One clear difference is that static groups are on average larger, with 20 ± 18 participants versus 5.4 ± 1.4 participants for the dynamic groups. On the other hand, dynamic communications tend to involve a larger fraction of their own group, and on a day that the dynamic group is active it will often use a larger percentage of the potential links at its disposal. Of the two groups considered in Fig. 7 Upper, the dynamic group uses a maximal fraction of 0.78 of potential links, compared with 0.33 used by the static group.

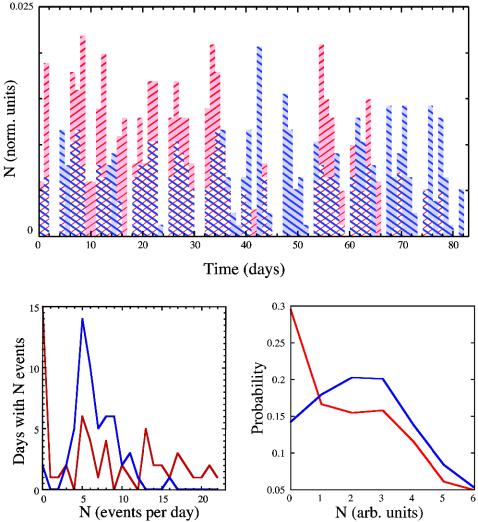

Fig. 7.

Comparison of dynamic (red) and static (blue) groups. (Upper) Time sequence for the 83 days on which data were taken, showing two groups of comparable size (dynamic group, 6 participants and a total of 505 events over the whole period; static group, 10 participants and a total of 389 events), with the sum of the activity normalized to 1. (Lower Left) Graph of events for the two groups shown in Upper, after removing weekends. (Lower Right) Averaged graph for all dynamic and all static groups after rescaling (on the x axis) by the maximal number of events and normalizing the distribution (on the y axis) to unity. norm. units, Normalized units; arb. units, arbitrary units.

Dynamic groups are additionally more intermittent than static groups. As seen in Fig. 7 Lower Left, the number of days on which a dynamic group is inactive is substantial. In comparison, if we disregard weekends, when practically all activity ceases, then there are almost no days when the static groups are silent (as is apparent in Fig. 7 Upper). Discarding weekends, we look at the graph of days with a given number of events (Fig. 7 Lower Left) and see that the dynamic group has a large peak near zero, whereas the static group has a Gaussian distribution with a nonzero peak. A measure of this phenomenon is the coefficient of variation CV, the ratio of the standard deviation of the distribution to its mean. We find that for dynamic groups CV = 0.78 ± 0.05, whereas for static groups CV = 0.56 ± 0.27, confirming that distributions for static groups are narrower (one outlier with a small number of participants slightly distorts the average for static groups). If we rescale and average over groups (Fig. 7 Lower Right), we can remove the effect of the mean and of the standard deviation: the essential two distributions remain. We find that the dynamic group's distribution of events peaks at zero and then decays, perhaps with a secondary peak, whereas the static group's distribution of events is more symmetric around a single average value.

Conclusions

Some sociological conclusions may also be drawn regarding the nature of communities that emerge by conducting a dialogue in the internet network. Two people engaged in a project can, if necessary, pick up the telephone and tie all loose ends efficiently. However, a group with three or more participants may find it hard to coordinate conference calls and in general will benefit from the lower time constraints that allow the participants (nodes) each to formulate their views and present them to a forum by e-mail. This makes e-mail an ideal medium for discussion groups involved in a given project or for a committee involved in a functional activity. Indeed, we have identified two committees in the clusters of Fig. 5 that are involved in nonacademic activities within the university. A third group can be identified as visiting scientists (e.g., postdoctoral fellows, etc.) from a common foreign nationality.

How unique are the human and sociological components of the interaction that we have studied? Comparison with the work of Ebel et al. (7) and preliminary work we have conducted on a second data set indicate that we are describing typical structures of universities. The choice of a university's e-mail network is perhaps not ideal for identifying such “groups of dialogue” because the major activity in a university is research, which usually involves few individuals and is almost never advanced by committee. We thus speculate that the role of dialogue in defining functional communities will be greater in large organizations such as companies (9) or government offices.

The collective effects uncovered by our work and, in particular, the methods of capturing them should be a general feature of spatiotemporal networks, because the phenomena we describe and quantify emerge whenever one is confronted with a large number of (a priori) independent agents interacting in a temporal fashion.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Collet for many helpful discussions and P. Choukroun and A. Malaspinas for help with the e-mail data. This work was supported by the Fonds National Suisse and by the Minerva Foundation (Munich).

Footnotes

We have confirmed a scaling law for the number of messages sent MS and the number of messages received MR per user, and we find that both occur with probabilities p(MS,R) ≈ MS,R-1.0 ± 0.1. The degree of the graph, i.e., the degree or number of links going in vin and out of vout a node, does not have a simple scaling behavior. Instead, one power law of v-0.93 characterizes the behavior of both vin and vout until v = 12, when a sharp transition to a second power law with v-1.84 fits the behavior until v ≈ 200, when our data end.

References

- 1.Eckmann, J.-P. & Moses, E. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5825-5829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milo, R., Shen-Orr, S., Itzkovitz, S., Kashtan, N., Chklovskii, D. & Alon, U. (2002) Science 298, 824-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert, R. & Barabási, A.-L. (1999) Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 47-97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinberg, J. M. & Lawrence, S. (2001) Science 294, 1849-1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cover, T. M. & Thomas, J. A. (1991) Elements of Information Theory (Wiley, New York).

- 6.Rieke, F., Warland, D., van Steveninck, R. R. & Bialek, W. (1997) Spikes: Exploring the Neural Code (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA).

- 7.Ebel, H., Mielsch, L.-I. & Bornholdt, S. (2002) Phys. Rev. E 66, 35103-35106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guimerà R., Danon, L., Díaz-Guilera, A., Giralt, F. & Arenas, A. (2003) Phys. Rev. E 68, 65103-65106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyler, J. R., Wilkinson, D. M. & Huberman, B. A. (2003) in Communities and Technologies, eds. Huysman, M., Wenger, E. & Wulf, V. (Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands), pp. 81-95.

- 10.Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. (1998) Nature 393, 440-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravasz, E. & Barabási, A.-L. (2003) Phys. Rev. E 67, 26112-26119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vazquez, A., Pastor-Sattoras, R. & Vespignani, A. (2002) Phys. Rev. E 65, 66130-66141. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorogovstev, S. N., Goltsev, A. V. & Mendes, J. F. F. (2002) Phys. Rev. E 65, 66122-66125. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinberg, J. M. (1999) J. Assoc. Comput. Mach. 46, 604-632. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldenfeld, N. & Kadanoff, L. P. (1999) Science 284, 87-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ay, N. & Knauf, A. (2003) Maximizing Multi-Information, preprint.