Abstract

Paralysis following spinal cord injury (SCI) is due to interruption of axons and their failure to regenerate. It has been suggested that the small GTPase RhoA may be an intracellular signaling convergence point for several types of growth-inhibiting extracellular molecules. Even if this is true in vitro, it is not clear from studies in mammalian SCI, whether the effects of RhoA manipulations on axon growth in vivo are due to a RhoA-mediated inhibition of true regeneration or only of collateral sprouting from spared axons, since work on SCI generally is performed with partial injury models. RhoA also has been implicated in local neuronal apoptosis after SCI, but whether this reflects an effect on axotomy-induced cell death or an effect on other pathological mechanisms is not known. In order to resolve these ambiguities, we studied the effects of RhoA knockdown in the sea lamprey central nervous system (CNS), where after complete spinal cord transection (TX), robust but incomplete regeneration of large axons belonging to individually identified reticulospinal (RS) neurons occurs, and where some RS neurons show unambiguous delayed retrograde apoptosis after axotomy. RhoA protein was detected in neurons and axons of the lamprey brain and spinal cord, and its expression was increased post-TX. Knockdown of RhoA in vivo by retrogradely-delivered morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (MOs) to the RS neurons significantly reduced retrograde apoptosis signaling in identified RS neurons post-SCI, as indicated by Fluorochrome Labeled Inhibitor of Caspases (FLICA) in brain wholemounts. In individual RS neurons, the reduction of caspase activation by RhoA knockdown began at 2 weeks post-TX and was still seen at 8 weeks. RhoA knockdown slowed axon retraction and possibly increased early axon regeneration in the proximal stump. The number of axons regenerating beyond the lesion more than 5 mm at 10 weeks post-TX also was increased. Thus RhoA knockdown both enhanced true axon regeneration and inhibited retrograde apoptosis signaling after SCI.

Keywords: RhoA, axon regeneration, neuronal death, FLICA, spinal cord injury, lamprey

Introduction

After spinal cord injury (SCI), axon regeneration is inhibited by several types of inhibitory molecules, such as the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (Omgp), Nogo, and their corresponding receptors (Yiu & He, 2006; Ferguson & Son, 2011). Accumulating evidence suggests that the intracellular signaling pathways for inhibition of axon growth by both CSPGs and CNS myelin proteins converge on the small GTPase RhoA, which makes it a potential therapeutic target (Monnier et al., 2003; Fu et al., 2007; Fisher et al., 2011), whose inhibition might produce stronger therapeutic effects on axon regeneration than manipulating single inhibitory molecules.

In primary neuronal cultures, inactivation of Rho with C3 transferase (C3), or of its downstream target Rho kinase (ROCK) with Y-27632, has enhanced neurite growth on myelin or CSPG substrates (Lehmann et al., 1999; Dergham et al., 2002; Fournier et al., 2003; Monnier et al., 2003; Bertrand et al., 2005). Consistently, ROCKII(−/−) dorsal root ganglion neurons (DRGs) are less sensitive to inhibition by Nogo or by CSPGs (Duffy et al., 2009) than wild type DRGs. Rho inactivation in retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) either at the lesion site or in the cell body promoted crushed optic nerves to regrow across the lesion (Lehmann et al., 1999; Bertrand et al., 2005). In ROCKII (−/−) mice, after dorsal root crush, axons regenerated across the dorsal root entry zone (DREZ) into the spinal cord (Duffy et al., 2009). Moreover, in mouse and rat, both neurons and glial cells showed activation of Rho at the site of SCI (Dubreuil et al., 2003). In rats, RhoA-positive cells accumulated at day 1 after injury, reached maximum levels at day 3, and remained significantly elevated until 4 weeks (Conrad et al., 2005). Either C3 or Y-27632 treatment was sufficient to promote functional recovery and growth of corticospinal tract (CST) fibers beyond a partial SCI in mice (Dergham et al., 2002; Boato et al., 2010). Enhanced CST axon growth into the lesion site and local growth of raphe-spinal axons after SCI have been shown in ROCKII (−/−) mice (Duffy et al., 2009). Y-27632 was reported to enhance sprouting of CST fibers and accelerate locomotor recovery after SCI in rats (Fournier et al., 2003). Taken together, studies in mammalian SCI models suggest a complicated and partial benefit of inhibiting Rho or ROCK. The incompleteness of the effect could be due to limitations in the intrinsic growth potential of mature mammalian neurons, to involvement by other kinases, or by poor access of the drugs to the target region in vivo. Alternatively, even though the ventral CST is very small in mice compared to rats, RhoA activity might be affecting collateral sprouting of spared CST or other axons rather than regeneration of the injured ones (Steward et al., 2003; Blesch & Tuszynski; Tuszynski & Steward, 2012).

Cell death remote from the site of axotomy occurs famously in RGC after optic nerve crush. Inactivation of Rho by injection of C3 into the eye delayed RGC death in rats for 1 week after injury (Bertrand et al., 2005). Whether RhoA is involved in retrograde cell death after SCI is not known. RhoA inactivation in both mouse and rat reduced the number of TUNEL-labeled cells (both neurons and glia) near the site of SCI by approximately 50%, indicating a role for activated Rho in cell death (Dubreuil et al., 2003). However, it is not known whether the neuronal death was due to axotomy, or to some other pathological process, e.g., inflammation, ischemia, or toxic effects of hemorrhage, since astrocytes and oligodendrocytes also were affected. This is difficult to resolve because retrograde neuronal death decreases with distance of axotomy from the neuronal perikaryon (Shifman et al., 2008; Conta Steencken et al., 2011), and it is controversial whether it occurs in supraspinal neurons of rodents after SCI (Novikova et al., 2000; Kwon et al., 2002; Nielson et al., 2010; Nielson et al., 2011).

Thus, due to the complexity of the mammalian spinal cord, and the need to use partial injury protocols, it is still unclear, despite intensive study, whether RhoA is involved in true regeneration of severed axons, as opposed to collateral sprouting by spared axons, and whether RhoA plays a role in retrograde neuronal death after SCI in vivo. In order to eliminate these ambiguities, we have used the lamprey spinal cord, in which regeneration of axons beyond a complete spinal cord transection (TX) has been documented extensively for many years (Selzer, 1978; Wood & Cohen, 1979; Yin & Selzer, 1983; Davis & McClellan, 1994). In the lamprey, the main descending system that transmits commands from the brain to the spinal cord is composed of reticulospinal (RS) neurons, which are responsible for initiation of locomotion, steering, and equilibrium control (Deliagina et al., 2000). Moreover, 18 pairs of individually identified RS neurons have axons that extend the entire length of spinal cord and therefore are always axotomized by a complete spinal cord TX. These RS neurons have heterogeneous regenerative abilities (Jacobs et al., 1997). The “bad-regenerating” neurons often experience very delayed retrograde apoptosis after spinal cord TX (Shifman et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). This allows us to test the role of inhibiting RhoA expression on retrograde neuronal death unambiguously. In the lamprey, fluorescently-labeled morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (MOs) are efficiently transported retrogradely from the site of axotomy, labeling the RS neurons (Zhang et al., 2015). MOs bind to complementary RNA to knock down gene expression specifically (Summerton, 2007). Thus we used MOs in vivo to inhibit RhoA expression and found that knockdown of RhoA significantly reduced retrograde apoptosis signaling and increased axon regeneration, suggesting that RhoA is an intracellular convergence point for both inhibition of true axon regeneration and retrograde neuronal death after SCI.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Surgery

Larval lampreys, Petromyzon marinus, 10–14 cm in length (4–5 years old), obtained from streams feeding Lake Michigan or Lake Champlain (Vermont), were maintained in fresh water tanks at room temperature (RT) until the day of use. Lampreys were anesthetized by immersion in saturated benzocaine solution, and the spinal cords were exposed dorsally in the gill region. The spinal cords were transected with Castroviejo scissors at the level of fifth gill, and the completeness of TX was confirmed by retraction and visual inspection of the cut ends. To deliver MOs retrogradely to the RS neurons, a pledget of Gelfoam soaked in fluorescein-tagged MO was inserted into the site of a complete TX. Afterwards, lampreys recovered on ice for 2 hours and were returned to fresh water at RT. To evaluate axon retraction and early regeneration in the proximal (rostral) stump, animals survived for 1 or 2 weeks post-TX, and the fluorescently-labeled axons were imaged by fluorescence microscopy. To evaluate axon regeneration beyond the lesion, animals were allowed to survive for 10 weeks post-TX. A second cut was made 5 mm caudal to the first, and a Gelfoam pledget soaked with 1µl 5% Dextran Tetramethylrhodamine (DTMR, 10 kDa, Molecular Probes) was inserted. After recovery, the lampreys were kept in fresh water for 1 more week and then sacrificed. The number of lampreys used was summarized in Table 3. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Temple University in accordance with the standards set by the National Institutes of Health.

Table 3.

Summary of lampreys treated with MO to study true axon regeneration after SCI.

| Experiments | Groups & lamprey no. |

Recovery Time | Axonal regeneration analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Ctr MO n = 6 RhoA MO n = 6 |

1 week | The distance between axon tips and TX site |

| Exp. 2 | Ctr MO n = 5 RhoA MO n = 5 |

2 weeks | The distance between axon tips and TX site |

| Exp. 3 | Ctr MO n = 5 RhoA MO n = 5 |

10 weeks | The number of identified neurons backfilled with DTMR |

Morpholino design, preparation and application

An antisense MO targeting the translation start-site of the lamprey RhoA gene (5’-GGCCGCCATTCCTGTAACCGCAAAC-3’-fluorescein) and a standard control MO (5’-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3’-fluorescein) were synthesized (Gene Tools). All the MOs were resuspended in distilled water at the stock concentration of 1 mM. The MOs were applied to the TX site as described above.

Brain dissection and fluorochrome-labeled inhibitor of caspases (FLICA) labeling

Lampreys were re-anesthetized by immersion in a saturated benzocaine solution. They were pinned to a Sylgard (184 silcone elastomer; Dow Corning Co., Midland, MI) plate filled with ice-cold lamprey Ringer’s solution (110 mM NaCl, 2.1 mM KCl, 2.6 mM CaCl2, 1.8 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Tris buffer; pH 7.4). Brains were dissected out and the posterior and cerebrotectal commissures of the freshly dissected brains were cut open along the dorsal midline. To evaluate caspase activity in brain neurons after spinal cord transection (Hu et al., 2013), the brains were incubated immediately at 4 °C for 1 hour in 150 µL 1 × FLICA labeling solution, diluted with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) from 150 × FLICA labeling solution (Image-iT™ Live Red Poly Caspases Detection Kit, Cat I35101, Molecular Probe™, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Afterwards, brains were washed with 1 × washing buffer on a rotator at 4 °C, 5 min × 5. The alar plates of brains were deflected laterally and carefully pinned flat to a small strip of Sylgard. The brains were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 2 hours at RT. After fixation, brains were washed 3 times in PBS at RT. The images of brains were captured immediately with a Nikon 80i fluorescence microscope. To evaluate axon regeneration at 10 weeks, the brains were dissected out as described above, pinned flat to Sylgard immediately and fixed with 4% PFA for 2 hours. All the samples were protected carefully from light. Control experiments were performed on brains without spinal cord TX. All images were acquired with a Nikon 80i microscope under the same parameters. The 18 pairs of identified RS neurons in each brain were counted as FLICA-positive or FLICA-negative, DTMR-positive or negative. The number of lampreys used was summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of lampreys treated with MO to study retrograde neuronal death in vivo after SCI.

| Experiments | Groups & lamprey no. |

Recovery Time | Apoptosis analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Ctr MO n = 6 RhoA MO n = 6 |

1 week | Number of FLICA

positive identified RS neurons |

| Exp. 2 | Ctr MO n = 8 RhoA MO n = 8 |

2 weeks | Number of FLICA

positive identified RS neurons |

| Exp. 3 | Ctr MO n = 5 RhoA MO n = 5 |

4 weeks | Number of FLICA

positive identified RS neurons |

| Exp. 4 | Ctr MO n = 5 RhoA MO n = 5 |

8 weeks | Number of FLICA

positive identified RS neurons |

Immunofluorescence Staining

To measure the knockdown effect of RhoA MO in individual axons, spinal cords were studied between the 2nd and 3rd gills. After fixation, dehydration and paraffin embedding, 10 µm thick paraffin sections were mounted onto glass slides for further investigation. The sections were de-paraffinized, rehydrated, and washed in PBS. MO fluorescence images were captured immediately. Antigen retrieval was performed: sections were immersed in the sodium citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0). The buffer was boiled for 20 minutes, and the sections allowed to cool for 20 minutes. Sections were rinsed in PBS twice for 5 minutes/each. All the sections were blocked with blocking buffer (10% FBS/0.2% Tween-20/PBS) for 1 hour at RT and incubated with primary antibody anti-RhoA (Cat SC-418, Santa Cruz) at 1:200 in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. Sections were washed 3 times with PBS, 10 minutes/each and then incubated with Goat anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor® 594 (Cat R37121, ThermoFisher Scientific) at 1:200, in blocking buffer for 1 hour at RT. All sections were washed 3 times with PBS, 10 minutes/each. After secondary antibody incubation, sections were washed with PBS and mounted with Fluoromount-G (Cat 0100-01, SouthernBiotech). All the images were acquired with a Nikon 80i microscope with consistent parameters in order to allow quantification of fluorescence. Between 7 and 15 sections were quantified for each lamprey (n=8 lampreys per group). With NIS-Elements AR 3.10, for each spinal cord section, all the axons filled with morpholinos were outlined, and the intensity of RhoA fluorescence measured in each axon. Background fluorescence intensity was measured by outlining the meninges adjacent to the spinal cord. The fluorescence intensity for each section was calculated as follows: The background fluorescence intensity was substracted from the mean fluorescence intensity within each axon in the same section. For each animal, the average fluorescence intensity from all the sections was calculated. Then an overall mean fluorescence was calculated as the mean of all these average intensities, and this is shown in the graph of Figure 2C. The number of lampreys used was summarized in Table 1.

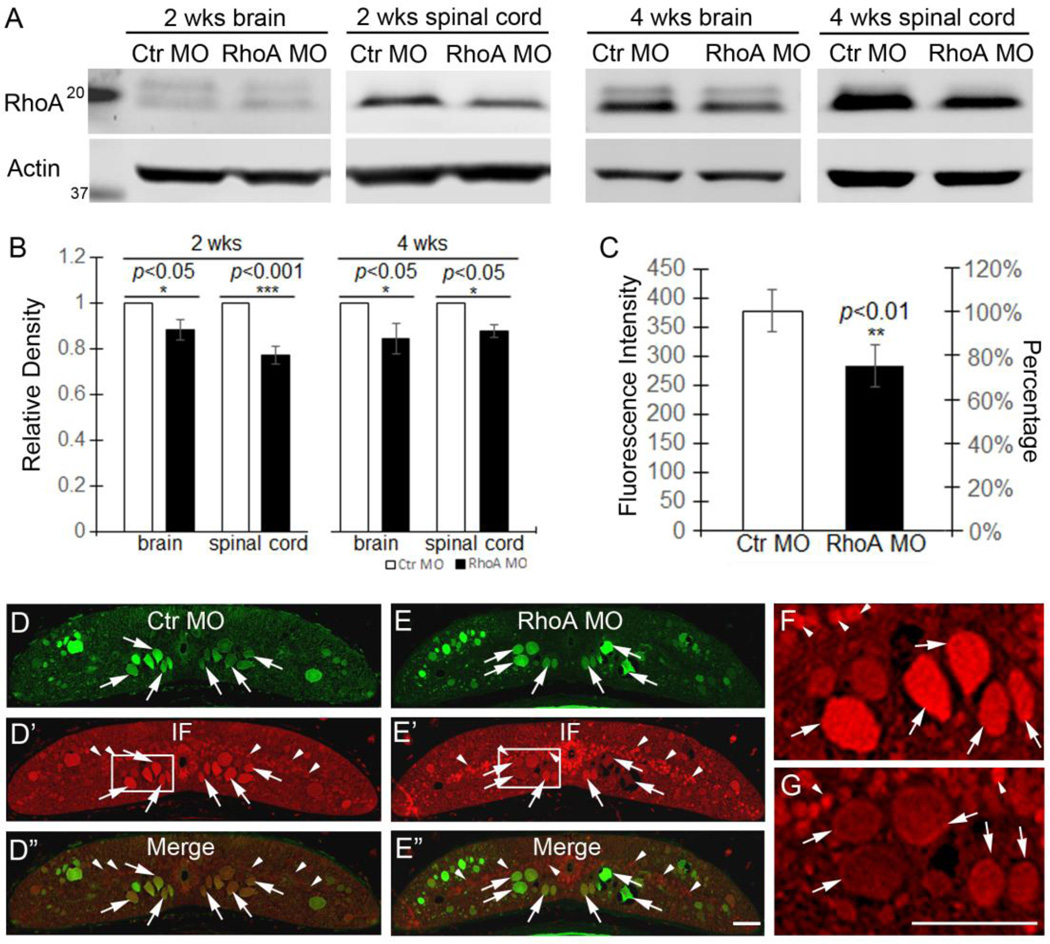

Figure 2. Effect of MO on RhoA levels in lamprey CNS.

A, Western blots of lamprey brain and spinal cord after 2 weeks and 4 weeks of MO treatment. The upper bands show the RhoA levels after control and RhoA MO treatments. The lower bands are the actin loading controls. B, the graph shows that RhoA MO reduces RhoA expression levels at 2 weeks in brain (~12%, p<0.05, n=7 lampreys/group) and spinal cord (~23%, p<0.001, n=8 lampreys/group). The RhoA MO knockdown effects persist at 4 weeks in brain (~16%, p<0.05, n=5 lampreys/group) and spinal cord (~13%, p<0.05, n=5 lampreys/group). Rho levels are normalized by actin loading controls and control MO animals. C, RhoA immunofluorescence intensity is reduced by approximately 20% in axons filled with RhoA MO, compared with axons containing control MO (p<0.05, n=8 lampreys/group). D–D”, RhoA immunofluorescence in control MO-treated spinal cord. E–E”, RhoA immunofluorescence staining RhoA MO-treated spinal cord. F, enlarged image from box in D’. G, enlarged image from box in E’. Arrows point to axons and arrowheads point to local cells. Scale bars in E” and G: 50 µm for D–E” and F–G, respectively. Note, the % reductions in Western blots and immunofluorescence probably underestimate the efficacy of MO treatment (see text).

Table 1.

Summary of lampreys used to study RhoA expression in vivo after SCI

| Experiments | Groups | Recovery Time | RhoA Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Brains | Ctr n=2; 2 wks n=2; total n=4 | Immunofluorescence Staining |

| Exp. 2 | Spinal cords |

Ctr n=2; 2 wks n=2; total n=4 | Immunofluorescence staining |

| Exp. 3 | Brains | Ctr n=8; 1 wk n=7; 2 wks n=8; 4 wks n=8; 8 wks n=8; total n=39 |

Western blots |

| Exp. 4 | Spinal Cords |

Ctr n=4; 1 wk n=4; 2 wks n=4; 4 wks n=4; 8 wks n=4; total n=20 (lampreys are from Exp. 3) |

Western blots |

| Exp. 5 | Brains | 2wks Ctr MO n=7; 2 wks RhoA MO

n=7; 4 wks Ctr MO n=5; 4 wks RhoA MO n=5; total n=24 |

Western blots |

| Exp. 6 | Spinal Cords |

2wks Ctr MO n=8; 2 wks RhoA MO

n=8; 4 wks Ctr MO n=5; 4 wks RhoA MO n=5; total n=26 |

Western blots |

Western blotting

The brains and spinal cords were collected from lampreys separately. In order to detect expression of RhoA in the spinal cord at and within 5 mm of a TX (with or without MO treatment), we dissected the approximately 10 mm fragment of spinal cord between the level of the 2nd gill and 5 mm caudal to the TX site. The tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in cold lysis buffer (C3228, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail (P8341, Sigma-Aldrich). After brief centrifugation to remove debris, the total protein concentration in supernatants was determined, using Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) DC protein assay reagents (#500-0006, Bio-Rad). After 10 minutes of heating at 75°C in loading buffer (NP 0007, Invitrogen) supplemented with reducing reagent (NP 0004, Invitrogen), 25 µg of protein were loaded from each sample. The protein was separated in 4–12% NuPAGE® Bis-Tris gradient mini gels (NP 0321BOX, Invitrogen), and transferred onto a PVDF membrane, using a Bio-Rad transblot apparatus. The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS buffer for 1 hour at RT. Membranes were probed with anti-RhoA antibody 1:600 (SAB1400017, Sigma) or anti-Actin 1:10,000 (MAB1501, Chemicon) at 4°C overnight. After washes with TBS, the blots were incubated in the dark with secondary antibodies IRDye 800RD Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (926-32210, LI-COR) or IRDye 680RD Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (926-68070, LI-COR) at 1: 20,000 for 1 hours at RT. The blots were washed 3 times with TBS, 10 minutes/each, scanned with an Odyssey CLx (LI-COR), quantified with Image J (U.S. National Institutes of Health) and processed in Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA). The number of lampreys used was summarized in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Data sets were analyzed with the InStat software (GraphPad), normally distributed data were further analyzed by InStat to determine if standard deviations were equal. For comparison between data sets with equal standard deviation (STD), the unpaired t-test was used. For Western blots, in order to avoid between-blot variation, all the groups were normalized against loading controls (actin). Then the experimental groups were compared with their respective normalized control groups, whose relative densities were assigned a value of 1. Then a paired t-test was performed to compare the density difference between groups. The effects of RhoA knockdown on apoptosis signaling was determined for individual identified neurons, by comparing FLICA labeling for the same RS neurons in control and RhoA MO-treated groups, using the paired t-test. For normally distributed data sets requiring multiple group comparisons, we used one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. For correlation analysis, we used the Pearson Correlation test. All values were expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

The lamprey brainstem contains 18 pairs of individually identified RS neurons (Jacobs et al., 1997) (Fig. S1A), whose regeneration probabilities have been determined previously (Jacobs et al., 1997; Busch & Morgan, 2012). Interestingly, the large RS axons do not demonstrate collateral sprouting after spinal cord hemi-TX, but only true regeneration (Zhang et al., 2015), and this, together with the ready regeneration after complete TX, allows us to study mechanisms of regeneration unambiguously. Moreover, after spinal cord TX many injured axon tips can be observed in vivo (Fig. S1B, C) (Zhang et al., 2005; Jin et al., 2009). The regenerating axons can cross the lesion after long-term recovery (Fig. S1C). We have taken advantage of these special characteristics to resolve several questions about the role of RhoA in axon regeneration after SCI.

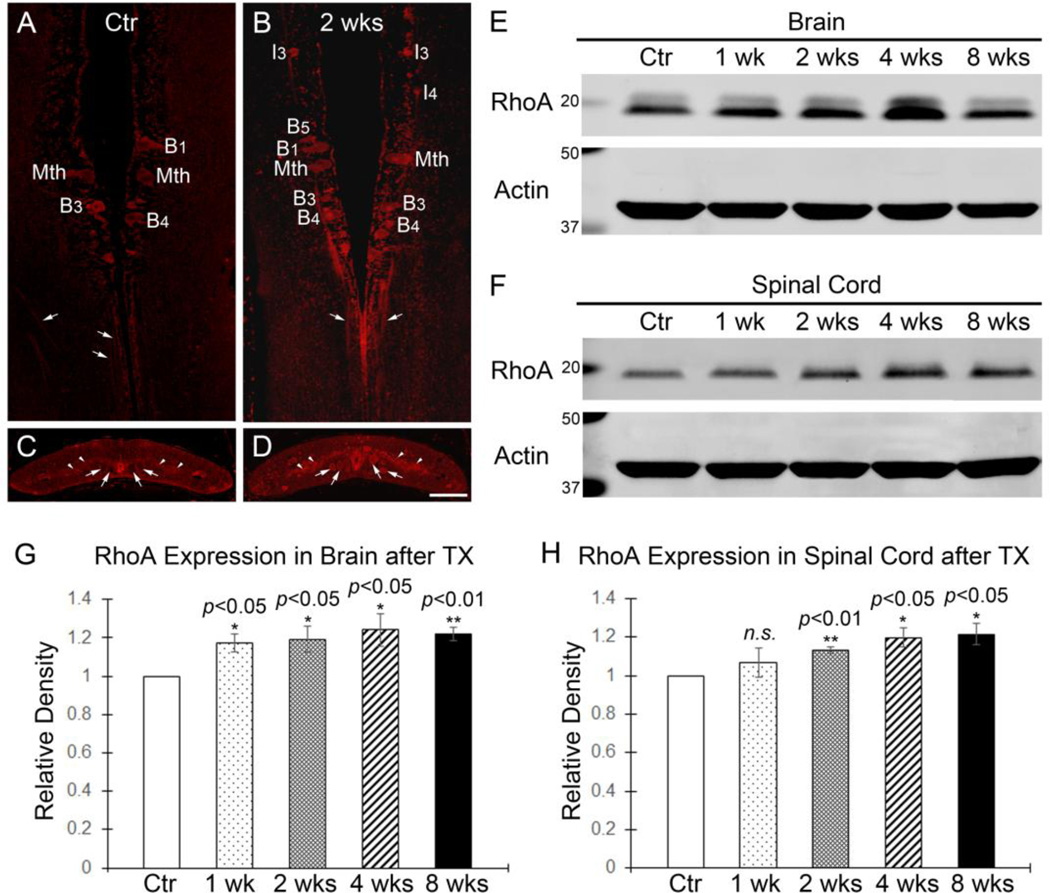

The effect of SCI on the Distribution and Expression of RhoA in lamprey CNS

Immunohistochemistry showed that RhoA and active Rho both are present in individually identified spinal-projecting neurons and axons in control lamprey brain (Fig. S2A, B). They also were found in axons and local cells in control spinal cord (Fig. S2C, D). The levels of RhoA appeared similar in CNS of lampreys of different lengths, i.e., different ages (Fig. S2E). At 2 weeks post-TX, RhoA immunofluorescence in identified neurons and axons was more intense (Fig. 1B, D) than in untransected controls (Fig. 1A, C), although the RhoA distribution pattern was unchanged (Fig. 1A–D). We further measured RhoA expression levels in brains and spinal cords at different post-TX times. RhoA was significantly elevated in brains after spinal cord TX at 1 week (17%, p<0.05, n=7), 2 weeks (19%, p<0.05, n=8), 4 weeks (24%, p<0.05, n=8) and 8 weeks (22%, p<0.01, n=8) (Fig. 1E, G) than in control animals. Remarkably, the increase in RhoA expression levels appeared 1 week later in the spinal cord than the changes in brain. It was increased by 13% at 2 weeks (p<0.01, n=4), 20% at 4 weeks (p<0.05, n=4) and 22% at 8 weeks (p<0.05, n=4) post-TX compared with control spinal cords (Fig. 1F, H).

Figure 1. RhoA protein expression and distribution in lamprey CNS.

A and B, Immunofluorescence (IF) demonstrating the presence of RhoA in identified RS neurons (B1, Mth, B3 and B4) in a control lamprey brain (A) and RS neurons (I3, I4, B1, B3, B4, B5 and Mth) at 2 weeks post-TX (B). Arrows point to axons in brains. These large individually identified spinal-projecting neurons are labeled according to the nomenclature of (Rovainen, 1967) as modified by (Swain et al., 1993) and (Jacobs et al., 1997). I, isthmic; B, bulbar; Mth, Mauthner cell. C and D, Transverse paraffin sections of control spinal cords (C) and spinal cords at 2 weeks post-TX (D) showed widespread presence of RhoA in local cells (arrowheads) and axons (arrows). Most labeled profiles in C and D are axons, whereas both perikarya and axons are seen in A and B. E and F, Western blots of RhoA in brains (E) and in spinal cords (F) at different post-TX times. The blots were reprobed with actin as a loading control. G, RhoA expression levels in brains are slightly increased at 1 week (p<0.05, n=7), 2 weeks (p<0.05, n=8), 4 weeks (p<0.05, n=8) and 8 weeks (p<0.01, n=8) post-TX, compared to control animals (n=8). H, RhoA expression levels in spinal cords at 1 week (p=0.4418, n=4), 2 weeks (p<0.01, n=4), 4 weeks (p<0.05, n=4) and 8 weeks (p<0.05, n=4) post-TX, compared to control animals (n=4). RhoA levels have been normalized relative to actin loading controls and against control animals. Scale: 100 µm.

RhoA MO effect on RhoA levels in lamprey CNS in vivo

We designed a RhoA MO to knock down RhoA in vivo and used multiple methods to assess its efficacy. Western blotting of lamprey brain and an approximately 10 mm spinal cord fragment spanning the TX site showed that the RhoA MO reduced expression of total RhoA significantly compared with control MO at 2 weeks in brain (~12%, p<0.05, n=7 lampreys/group) and spinal cord (~23%, p<0.001, n=8 lampreys/group) respectively (Fig. 2A, B). The knockdown effect persisted at 4 weeks in brain (~16%, p<0.05, n=5 lampreys/group) and spinal cord (~13%, p<0.05, n=5 lampreys/group) (Fig. 2A, B). This probably underestimates the efficiency of the MO knockdown because the results are diluted by the RhoA contained in neurons and glial cells that were not axotomized and did not take up the MO, and because we do not know the turnover rate of RhoA protein, nor whether this might change to compensate for reduced mRNA expression. In transverse sections of lamprey spinal cord, it is easy to distinguish the large RS axons from local cells (Fig. S2C, D). To determine RhoA MO knockdown efficiency more specifically, we paid extra attention to individual axons, which were filled with MOs. We compared axons filled with RhoA MO with axons containing the control MO. The averaged immunofluorescence intensity of all the individual axons in RhoA MO-treated animals showed a significant knockdown effect of approximately 25%, compared with axons in control MO-treated animals (Fig. 2C, D–D”, E–E”, F, G; p<0.01, n=8 lampreys/group). We also performed RhoA immunofluorescence staining on transverse sections of spinal cord at longer post-TX times (Fig. S3) to confirm persistence of the knockdown effects. The individual RS axons containing RhoA MO showed reduced RhoA expression at 4 weeks (Fig. S3A, B; n=1 lamprey/group), 7 weeks (Fig. S3C, D n=1 lamprey/group) and 10 weeks (Fig.S3E, F; n=1 lamprey/group) compared with axons containing control MO.

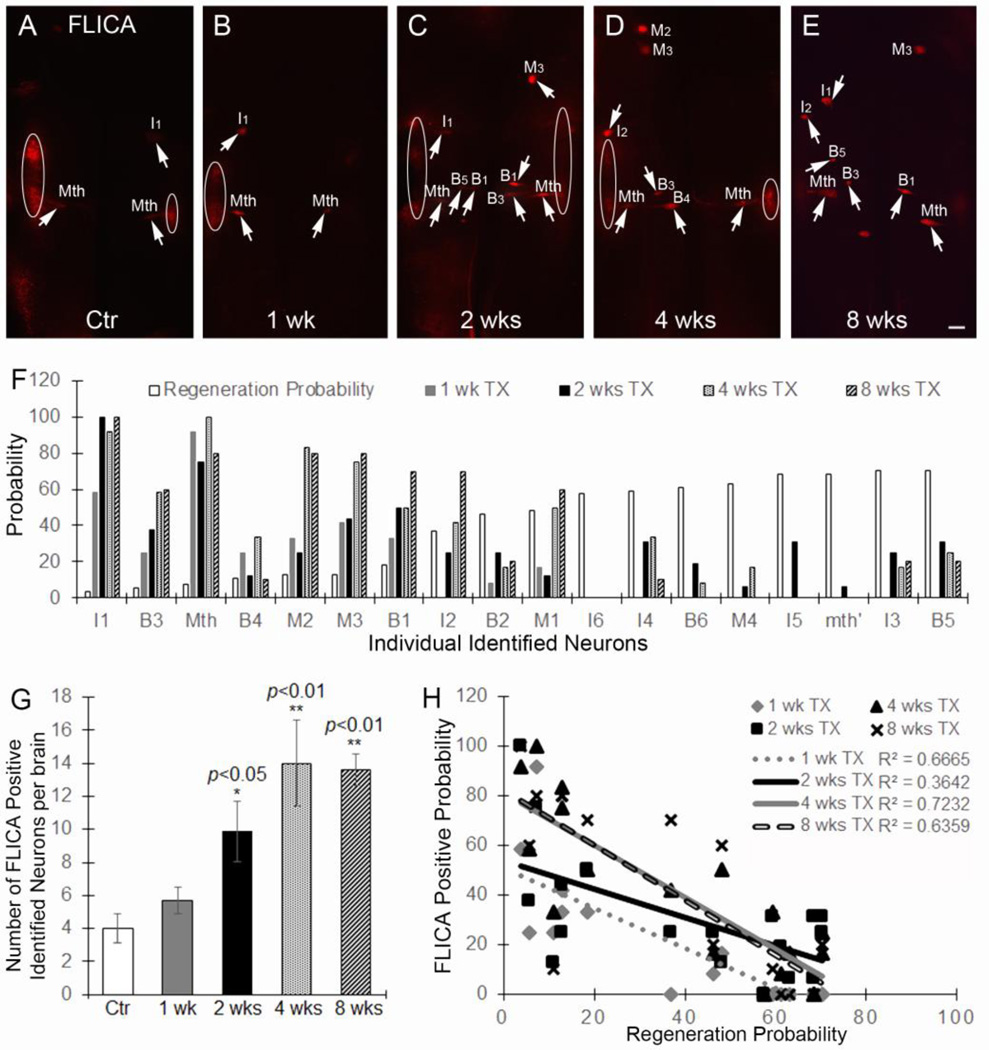

FLICA predicts the fate of individual identified RS neurons after SCI

Using the FLICA method adapted by us for lamprey wholemounted brains (Hu et al., 2013), control brains showed activated caspases in very few neurons (Fig. 3A, G). At 1 week post-TX, more neurons were caspase positive, but the change was not statistically significant (Fig. 3B, G). At 2 weeks post-TX, the number of FLICA-positive neurons was greatly increased (p<0.05, Fig. 3C, G), and this persisted at 4 weeks (p<0.01, Fig. 3D, G) and 8 weeks (p<0.01, Fig. 3E, G). These observations are consistent with those described in our previous reports (Shifman et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). Interestingly, the increase in FLICA-positive neurons followed a similar post-TX time course as RhoA expression changes (Fig 1A, B, E, G), suggesting that RhoA might be involved in apoptosis signaling. Moreover, at 1, 2, 4 and 8 weeks post-TX, the probability of caspase labeling in individual identified neurons correlated inversely with their known probability of axon regeneration (Fig. 3F, H). The inverse correlation was statistically significant at all time points studied (1 week, R2=0.6665, p<0.0001; 2 weeks, R2=0.3642, p<0.01; 4 weeks, R2=0.72325, p<0.0001; 8 weeks, R2=0.6359, p<0.0001), suggesting that as an apoptosis signaling indicator, FLICA also can predict whether individual identified neurons will undergo axon regeneration after SCI.

Figure 3. Caspases are activated in identified RS neurons after spinal cord transaction.

A–E, activated caspases in brains at 0 (uninjured controls), 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after SCI. Note that caspases activity usually is seen in cranial motor neurons (circled) in the lateral areas of the brainstem, due to rapid activation in the axons at the time of live brain dissection. M, Mesencephalic; I, isthmic; B, bulbar; Mth, Mauthner cell. (Rovainen, 1967; Swain et al., 1993; Jacobs et al., 1997). Scale: 100 µm for all frames. F, the previously-determined probability of axon regeneration at 10 weeks post-TX for each identifiable RS neuron is compared with the probability that the neuron has become caspase positive at different times post-TX. G, the number of caspase-positive neurons per brain after SCI. At 1 week, there was no significant change (p>0.05, n=5). At 2, 4, and 8 weeks, the number of caspase positive neurons increases greatly (2 weeks: p<0.05, n=8; 4 weeks: p<0.01, n=5; 8 weeks: p<0.01, n=5). H, the data from F is graphed to show the inverse correlation between regenerative ability and the probability that an RS neuron is caspases positive at different times post-TX (1 week: r2=0.6665, p<0.0001; 2 weeks: r2=0.3642, p<0.01; 4 weeks: r2=0.7232, p<0.0001; 8 weeks: r2=0.6359, p<0.0001).

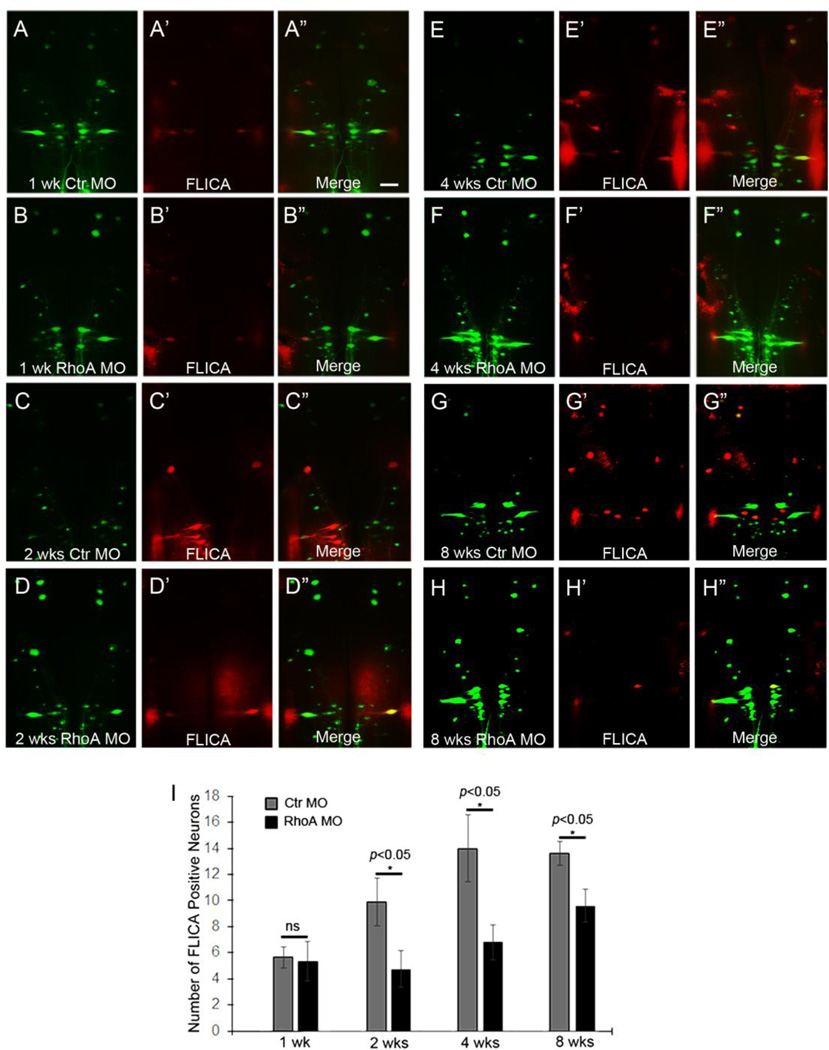

RhoA knockdown confers extended protection of neurons from retrograde neuronal death in vivo

It has been reported that blocking Rho activation after SCI protects local cells from p75-dependent apoptosis in mouse spinal cord (Dubreuil et al., 2003). C3 injected into the retina prevented RGC cell death for 1 week after axotomy (Bertrand et al., 2005). However, there is no study showing whether RhoA inhibition will protect neurons in brain from retrograde apoptosis after SCI and whether this protection will last longer than 1 week. As we have shown, RhoA expression levels in brain were enhanced after spinal cord transection (Fig. 1A, B, E, G), and the numbers of FLICA-positive identified neurons in brain were also greatly increased (Fig. 3A–G). Therefore, it is critical to determine whether RhoA is involved in retrograde neuronal death after SCI and whether in vivo knockdown of RhoA can protect neurons from dying and promote axon regeneration.

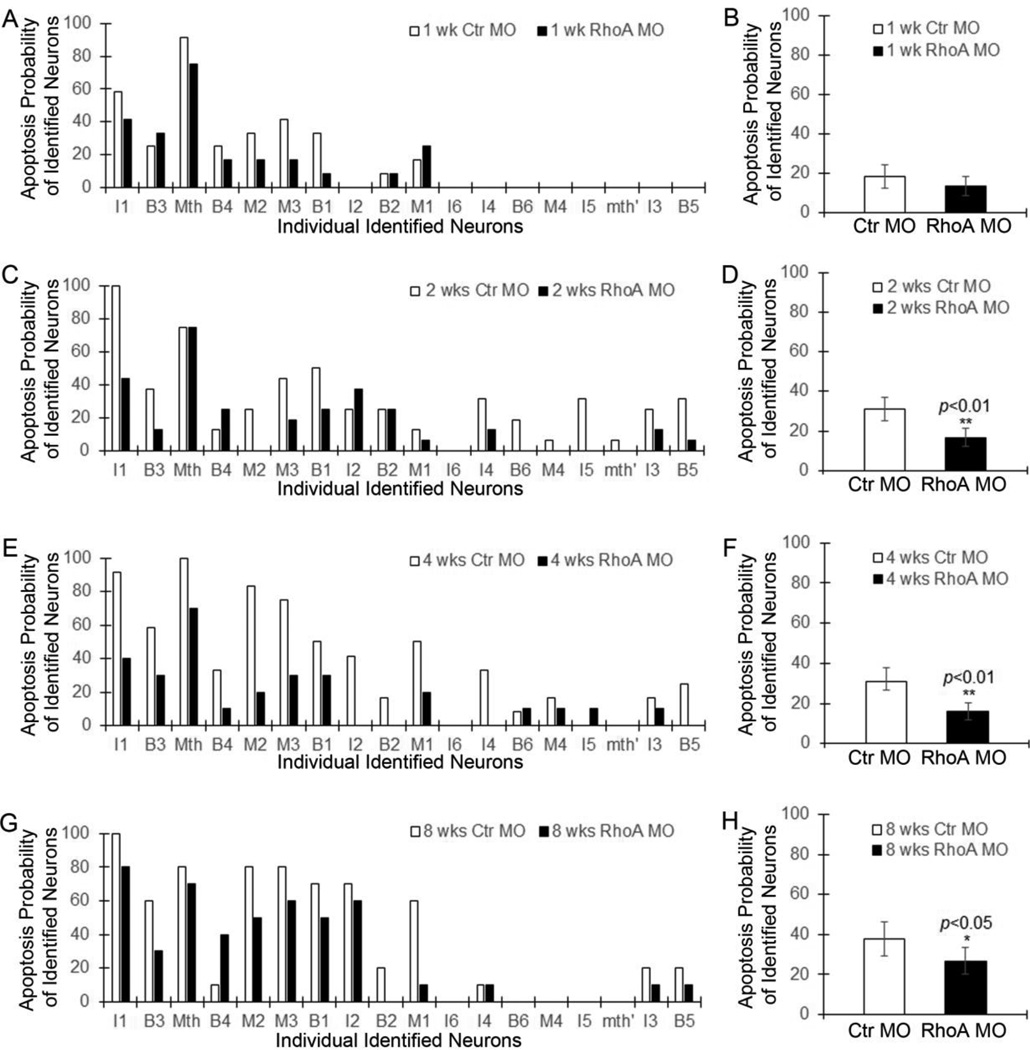

We applied control or RhoA MOs to the TX site and investigated the activities of caspases in identified neurons at 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after SCI. The total number of FLICA-positive identified neurons had no change by RhoA knockdown at 1 week post TX (Fig. 4A–A”, B–B”; p>0.05, n=6 lamprey/group; Fig. 5A, B, p>0.05), while it was greatly reduced by RhoA knockdown at 2 weeks (Fig. 4C–C”, D–D”; p<0.05, n=8 lamprey/group), 4 weeks (Fig. 4E– E”, F–F”; p<0.05, n=5 lamprey/group), and 8 weeks (Fig. 4G–G”, H–H”; p<0.05, n=5 lamprey/group) after SCI. The protection was apparent at early times post-TX (2 weeks, p<0.01, Fig. 5C, D; 4 weeks, p<0.01, Fig. 5E, F) and lasted at least 8 weeks (p<0.05, Fig. 5G, H). Since there is very few neurons that are FLICA positive at 1 week post-TX (Fig. 4B–B”, 5B), it is not surprising that we didn’t find the significant reduction of apoptosis after RhoA knockdown. On the other hand, RhoA MO did not fully block the increase of FLICA-positive identified neurons, especially after 8 weeks recovery (Fig. 4I). But the effect of RhoA knockdown to reduce FLICA labeling was significant when compared with controls even at 8 weeks post-TX, and was especially pronounced in RS neurons that are poor regenerators because ordinarily they also are poor survivors (Fig. 5A, C, E, G). Thus, the reduction of FLICA labeling by RhoA MOs suggests that RhoA is involved in the retrograde neuronal death observed after SCI, and that RhoA knockdown is beneficial for neuronal survival after axotomy in vivo.

Figure 4. RhoA knockdown protects neurons from retrograde neuronal death in vivo after SCI.

Activated caspases in control MO-treated (A–A”, C–C”, E–E”, G–G”) and RhoA MO-treated (B–B”, D–D”, F–F”, H–H”) brains at 1 week (A–A” & B–B”), 2 weeks (C-C” & D–D”), 4 weeks (E–E” & F–F”), and 8 weeks (G–G” & H–H”) post-TX. Scale: 200 µm for all frames. I, RhoA knockdown reduces the number of caspases-positive neurons significantly at 2 weeks (p<0.05, n=8/group), 4 weeks (p<0.05, n=5/group), and 8 weeks (p<0.05, n=5/group) post-TX.

Figure 5. RhoA knockdown greatly reduces apoptosis signaling in RS neurons in vivo.

The graphs show the probability of apoptosis signaling in individual identified neurons after treatment with control MO and RhoA MO at 1 week (A), 2 weeks (C), 4 weeks (E) and 8 weeks (G) post-TX. The mean probabilities of all the identified RS neurons that become caspase-positive after treatment with control MO and RhoA MO are shown at 1 week (B), 2 weeks (D), 4 weeks (F) and 8 weeks (H) post-TX.

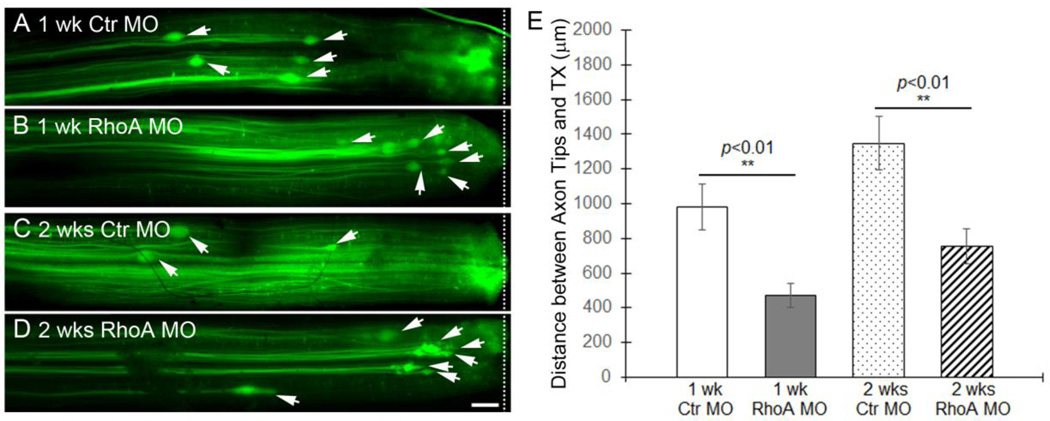

In vivo RhoA knockdown inhibits axon retraction in the proximal (rostral) stump

During the first 10–14 days after SCI in the lamprey, severed axons retract and then begin to grow forward toward the lesion, reaching the injury scar by 4 weeks. During this time, the axon tips can be imaged in vivo and regeneration can be assessed by measuring the distance of the tips from the lesion site (Zhang et al., 2005; Jin et al., 2009). We transected the spinal cords at the level of the 5th gill and applied either a control or RhoA MO to the injury site for 1 or 2 weeks. The whole-mounted free spinal cords were fixed and imaged by fluorescence microscopy, so that the distance between individual axon tips (arrows in Fig 6A–D) and the lesion site (dashed line in Fig 6A–D) could be measured. At 1 week post-TX, the distance in RhoA MO-treated lampreys (472.40 ± 67.23 µm, n=25 axons from 6 lampreys) was approximately half that in control MO-treated ones (980.01 ± 133.48 µm; n=35 axons from 6 lampreys, p<0.01) (Fig. 6A, B, E). This suggested that RhoA knockdown reduced the amount of axon retraction, either by reducing the maximum distance of retraction, or by hastening the onset of regeneration. However, at 2 weeks post-TX, the mean distance between the axon tips and the lesion site in RhoA MO-treated spinal cords (752.03 ± 101.18 µm; n=20 from 5 lampreys) was greater than that at 1 week, and was slightly more than half that in control MO-treated ones (1349.03 ± 155.93 µm; n=30 from 5 lampreys, p<0.01) (Fig. 6C, D, E). Thus in both control and RhoA MO-treated animals, RS axons continued to retract during the second week post-TX, and differences between the two groups during the first week post-TX must have reflected a reduced rate of retraction in the RhoA MO-treated group. Whether axons in either group had begun to regenerate toward the lesion during the second week post-TX cannot be determined from these data.

Figure 6. RhoA knockdown slows initial axon retraction in vivo after spinal cord transaction.

A and B, Axon tips (arrows) in the spinal cord of lamprey back-filled with control MO (A) and RhoA MO (B) at 1 week post-TX (n=6 lampreys/group). C and D, axon tips (arrows) in the spinal cord of lamprey back-filled with control MO (C) and RhoA MO (D) at 2 weeks post-TX (n=5 lampreys/group). E, mean distances of axon tips from the center of the TX site (dashed line). N = number of axon tips. ** different from control at the same post-TX time, p<0.01. Note that the distances of both control and RhoA MO-filled axon tips at 2 weeks are greater than their corresponding distances at 1 week, although the differences did not reach statistical significance (p>0.05). Scale: 200 µm.

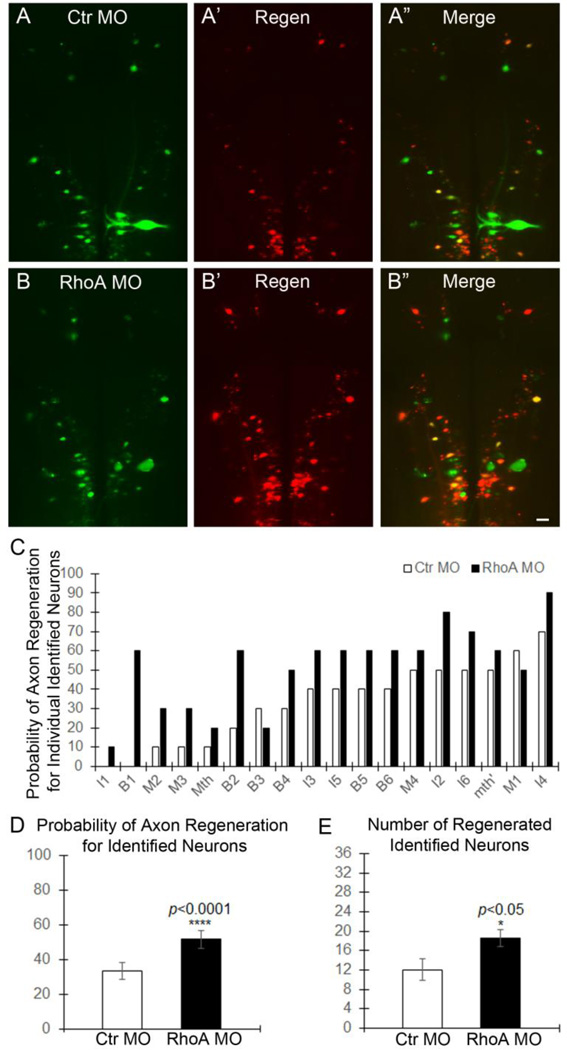

In vivo RhoA knockdown increased axon regeneration beyond the TX

As axons regenerate through and beyond the TX, their diameters decrease, their paths are slightly more tortuous, and they intermingle with axons of spinal cord neurons regenerating rostral-ward. This makes them difficult to follow in wholemount preparations. Therefore, in order to determine whether RhoA knockdown promotes long-term axon regeneration beyond the injury, at 10 weeks after TX and treatment with MO, and to determine which neurons had regenerated their axons, we labeled RS neurons retrogradely with a second dye (DTMR) inserted into a second TX 5 mm caudal to the original injury (Fig. 7A–A”, B–B”). After another week, we imaged the brainstem and determined which identified RS neurons were labeled with DTMR and thus had axons that regenerated as far as 5 mm caudal to the original TX. The change in probability of axon regeneration for each of the 18 pairs of identified RS neurons is shown in Fig. 7C. For all but one of these neurons (B3), the probability of regeneration was greater in the RhoA MO group than in the control MO group. This represents an increase in the probability of axon regeneration for identified RS neurons from 33.33±4.92% to 51.67±5.07% (n=5 lampreys/group; 18 pairs of identified neurons were analyzed in each lamprey, p<0.001; Fig. 7D). For all the identified neurons, RhoA knockdown significantly increased the number of DTMR back-labeled identified RS neurons by 50% (18.6±1.69 vs. 12±2.21 per brain, p<0.05, n=5 lampreys/group; Fig. 7E). Taken together, these results indicate that RhoA knockdown in vivo significantly enhances axon regeneration beyond the TX site.

Figure 7. RhoA knockdown promotes axon regeneration in vivo after spinal cord transection.

A–A” and B–B”, Regenerated identified RS neurons in brain at 10 weeks post-TX. A, RS neurons labeled with fluorescently-tagged control MO; A’, neurons whose axons regenerated, retrogradely labeled with DTMR; A”, overlay of A & A’. B–B”, RhoA MO as in A–A”. Scale: 100 µm for all frames. C, the probability for each identified neuron that its axon will have regenerated at 10 weeks post-TX. D, the mean probability of axon regeneration for all of the identified neurons at 10 weeks post-TX (p<0.0001, n=5 lampreys/group, 18 pairs of identified neurons were analyzed from each lamprey). E, the mean number of identified neurons whose axons have regenerated at 10 weeks post-TX (p<0.05, n=5 lampreys/group).

Discussion

RhoA can be activated by CSPGs, MAG and Nogo (Niederost et al., 2002; Monnier et al., 2003; Jain et al., 2004; Madura et al., 2004; Fu et al., 2007), and thus appears to be a critical point of convergence that integrates multiple extracellular inhibitory signals after SCI. Consistent with previous results in mammals (Dubreuil et al., 2003; Conrad et al., 2005), RhoA expression levels in lamprey spinal cord were increased by SCI (Fig. 1C, D, F, H). More importantly, our study found that RhoA expression was also elevated in lamprey brain after SCI (Fig. 1A, B, E, G), and correspondingly, more individually identified RS neurons showed apoptosis signaling, indicating that RhoA may be involved in retrograde neuronal apoptosis signaling (Fig. 3).

Retrograde neuronal death and atrophy after SCI

Previous studies from our lab and others’ showed that a very delayed form of retrograde neuronal death occurs in spinal-projecting neurons of the brain after SCI in lampreys (Shifman et al., 2008; Busch & Morgan, 2012; Hu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). Similar phenomena have been reported in mammals (Mori et al., 1997; Houle & Ye, 1999; Novikova et al., 2000; Hains et al., 2003). Cell death occurs near the lesion site in mammalian SCI (Crowe et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1997; Dubreuil et al., 2003), but this is not restricted to neurons and the degree to which this involves axotomy is unclear. Whether SCI triggers substantial retrograde cell death in the brain is controversial (Novikova et al., 2000; Kwon et al., 2002; Nielson et al., 2010; Nielson et al., 2011). Some studies indicated that axotomy results in only atrophy of rubrospinal and CST neurons (Kwon et al., 2002; Nielson et al., 2010; Nielson et al., 2011). These studies did not identify the axotomized neurons by retrograde labeling, did not count surviving neurons, and did not use multiple detection methods for apoptosis such as caspases and TUNEL staining (Novikova et al., 2000; Hains et al., 2003; Shifman et al., 2008; Busch & Morgan, 2012; Hu et al., 2013). It also may be that differences in results among these studies relates to the distance of axotomy from the cell body. In the lamprey, retrograde death of RS neurons was seen if the spinal cord TX was made at the level of the gills, but not when the same axons were severed by TX in the caudal spinal cord (Shifman et al., 2008). A similar effect was suggested in the death of rat propriospinal neurons (Conta Steencken et al., 2011), and in rat corticospinal neurons whose axons were injured in the subcortical white matter, rather than in the spinal cord (Hollis et al., 2009). Perhaps most famously, massive (80–90%) retrograde neuronal death is seen in rodent RGCs after optic nerve injury (Berkelaar et al., 1994). But these lesions are generally made intra-orbitally within 1 mm of the retina, so that other mechanisms such as ischemia or inflammation may contribute to the neuronal death. Thus although there is little doubt that injuries that result in axotomy can cause retrograde neuronal death, this depends on cell type and distance of injury from the cell body, and the relationship to the axotomy itself is not always clear.

In the lamprey, we can track the fate of individually identified RS neurons, and thus the ambiguities noted in the mammalian studies can be avoided. The identified RS neurons in lamprey have pre-determined heterogeneous regeneration probabilities (Davis & McClellan, 1994; Jacobs et al., 1997), and those that regenerate poorly also undergo a very delayed (16 weeks) form of apoptosis (Shifman et al., 2008; Busch & Morgan, 2012; Zhang et al., 2014). The death of these RS neurons is due to axotomy because of the distance of the brainstem from the transection (approximately 1.5 cm) and the long delay in onset of caspases labeling (Fig. 3–5). After the transection, there is no evidence for ischemic change or hemorrhage in the brain, which would be expected to have a rapid time course. Previously we showed that an inflammatory response consisting of microglial proliferation and reactive expression of repulsive guidance molecule (RGM) occurred within 0.5 mm from TX site, declining greatly at further distances. No reactive cells at all were seen beyond 10 mm from the transection, and did not extend as far as the brainstem (Shifman et al., 2009).

We used FLICA to detect activated caspases in wholemounted brains (Hu et al., 2013) (Fig. 3 and Fig 4). Control brains showed little caspase activity (Fig. 3A), while after spinal cord TX, caspase activity increased greatly at 2–8 weeks (Fig. 3B–E). These results are consistent with our previous reports (Shifman et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014) that the identified RS neurons undergo retrograde death, not only atrophy. In future experiments designed to further dissect the role of RhoA in vivo, we will determine whether expression levels of RhoA are correlated with caspase activity in individually identified neurons.

Effect of RhoA knockdown on retrograde neuronal death

After SCI in both mouse and rat, inactivating RhoA with C3 reduced the number of TUNEL-labeled cells near the lesion by approximately 50% (Dubreuil et al., 2003), although, as indicated above, the relationship of the cell death to axotomy is not clear. Perhaps more convincingly, the death of axotomized RGCs during the first week after optic nerve injury was completely prevented by a single intraocular injection of C3 (Bertrand et al., 2005), suggesting that RhoA plays a role in mediating short-term retrograde neuronal death. Once again, the closeness of the optic nerve crush to the retina leaves open the possibility that the effect of C3 was to protect against neuronal death due to mechanisms other than axotomy, and this possibility might be reflected in the rapidity of the cell death that was studied. Retrograde death of RGCs has been observed when the crush was made further from the retina, and interestingly, the latency of this apoptotic death was much longer, but the effect of RhoA activity on this more delayed death is not known. Thus, the role of RhoA in the very delayed form of retrograde neuronal death seen in the RS neurons after axotomy in lamprey is not well established. In the present study, knockdown of RhoA with MO in vivo significantly reduced retrograde apoptotic signaling as indicated by FLICA labeling in identified RS neurons after SCI (Fig 4, 5). The reduction was observed at 2 and 4 weeks post-TX (Fig 4C–C”, D–D”, E–E” and F–F”) and was still apparent at 8 weeks (Fig 4G–G ” and H–H”), suggesting that RhoA plays a critical role in delayed retrograde neuronal death after SCI. MO transport was not perfect and some RS neurons were not labeled with MO after its application to the site of TX. Some of these neurons were FLICA positive. This further supports the conclusion that RhoA activity promotes retrograde neuronal death. The pathway downstream of RhoA that underlies this effect is not known, but unpublished observations indicate that RhoA knockdown increases Akt phosphorylation levels in our system. Further elucidation of the signaling pathway responsible for this cell death could help us to understand how to protect neurons from axotomy-induced neuronal death.

Effect of RhoA knockdown on initial axon retraction

RhoA MO knockdown in vivo reduced axon retraction at 1 week post-TX by approximately 50% (Fig. 6A, B). From this alone, one could not conclude that the treatment reduced the maximum distance or rate of retraction. The injured axon tips might already have begun to grow forward, and the effect observed might have represented acceleration of axon regeneration. However, because at 2 weeks post-TX (Fig. 6C, D), the average distance between the axon tips and the TX site was greater than it had been at the end of 1 week, it is likely that the axons were still retracting during the second week. Therefore, the effect of RhoA knockdown during the first week represented a reduction in the net rate of retraction. These findings are consistent with findings of two studies in vitro. Inhibition of ROCK reduced axon retraction in embryonic chicken DRG and retinal explants (Gallo, 2004). Inhibition of RhoA or ROCK reduced axon retraction in an in vitro model of acute retinal detachment in pig (Fontainhas & Townes-Anderson, 2011). To our knowledge, no previous study has addressed the effect of RhoA inhibition on axon retraction post-axotomy in vivo. Since in mammals, there is no tractable axon tips formed after SCI and it is impossible to study in vivo RhoA effect on invidiual axons. Thus, we are the first that provided evidence for this effect in vivo.

Effect of RhoA knockdown on regeneration beyond the TX

Although RhoA inhibited axon growth after SCI in mammals, whether this represents an effect on true regeneration or only collateral sprouting is not clear. In most experiments that studied effects of pharmacological or molecular interventions on axon growth after SCI, partial injury models were used (Lehmann et al., 1999; Dergham et al., 2002; Fournier et al., 2003; Bertrand et al., 2005; Duffy et al., 2009; Boato et al., 2010). Thus the possibility that the beneficial effects are due to an increase in axon sparing or in collateral sprouting cannot be excluded.

To study regeneration beyond the TX, we introduced a retrograde tracer from a second TX 5 mm caudal to the first lesion at 10 weeks after the initial injury (Fig. 7). The probabilities of regeneration measured in this way underestimate the amount of axon regeneration to the extent that retrograde labeling efficiency is less than 100%. Indeed, this method does not detect many neurons whose axons regenerated less than 5 mm beyond the first TX. Nevertheless, in the present study, in vivo RhoA knockdown greatly increased the probability of an axon regenerating beyond the TX site (Fig. 7). Unlike the situation in mammalian SCI studies, because our SCI model is a complete TX, the growth of RS axons caudal to the lesion represents true regeneration of injured axons, not collateral sprouting of spared axons. Indeed, after spinal cord hemi-section in lamprey, collateral sprouting was not observed (Zhang et al., 2015). Thus the present findings add evidence to support therapeutic use of RhoA inhibitors to promote true axon regeneration after SCI.

Conclusions

Previous studies have used C3 to inhibit RhoA activation and investigate the role of RhoA in local cell death (Dubreuil et al., 2003) and axon sprouting (Lehmann et al., 1999; Dergham et al., 2002; Ellezam et al., 2002; Boato et al., 2010) after SCI. Whether RhoA inhibition protects neurons from retrograde apoptosis and promotes regeneration of the injured axons was unclear. In the current study, we used fluorescently-tagged MOs to simultaneously knock down RhoA and label the axotomized axons and neurons. This, together with the anatomical advantages of the lamprey, has allowed us to determine that the neurons undergoing apoptosis were indeed axotomized, that the delayed neuronal death was due to the axotomy, and that inhibiting RhoA expression promoted true axon regeneration after SCI. These effects may well interact, i.e., improved neuronal health and survival might well improve the probability of axon regeneration, while axon regeneration could reduce the likelihood of very delayed neuronal death that has been described in their perikarya (Shifman et al., 2008) by permitting axons to gain access to additional target-derived trophic support. On the other hand, there may be a more specific convergence of signaling pathways for neuronal survival and axon regeneration after axotomy. Future studies will determine if this is so, and how this might be used therapeutically after SCI.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

In Vivo RhoA knockdown reduced retrograde apoptosis signaling in identified RS neurons after SCI, beginning 2 weeks post-TX and still observed at 10 weeks.

In Vivo RhoA knockdown reduced axon retraction, and then increased axon regeneration beyond the lesion at 10 weeks post-TX.

RhoA knockdown may be useful not only to enhance axon regeneration, but also to protect neurons from retrograde neuronal death after SCI.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants R01-NS092876 (NIH, M.E. Selzer PI), SHC-85400 (Shriners Research Foundation, M.E. Selzer, PI), SHC-85220, (Shriners Research Foundation, M.E. Selzer, PI), SHC-84293, (Shriners Research Foundation, J. Hu, PI)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berkelaar M, Clarke DB, Wang YC, Bray GM, Aguayo AJ. Axotomy results in delayed death and apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells in adult rats. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4368–4374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04368.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand J, Winton MJ, Rodriguez-Hernandez N, Campenot RB, McKerracher L. Application of Rho antagonist to neuronal cell bodies promotes neurite growth in compartmented cultures and regeneration of retinal ganglion cell axons in the optic nerve of adult rats. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1113–1121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3931-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Spinal cord injury: plasticity, regeneration and the challenge of translational drug development. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boato F, Hendrix S, Huelsenbeck SC, et al. C3 peptide enhances recovery from spinal cord injury by improved regenerative growth of descending fiber tracts. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1652–1662. doi: 10.1242/jcs.066050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch DJ, Morgan JR. Synuclein accumulation is associated with cell-specific neuronal death after spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:1751–1771. doi: 10.1002/cne.23011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad S, Schluesener HJ, Trautmann K, et al. Prolonged lesional expression of RhoA and RhoB following spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2005;487:166–175. doi: 10.1002/cne.20561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conta Steencken AC, Smirnov I, Stelzner DJ. Cell survival or cell death: differential vulnerability of long descending and thoracic propriospinal neurons to low thoracic axotomy in the adult rat. Neuroscience. 2011;194:359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe MJ, Bresnahan JC, Shuman SL, Masters JN, Beattie MS. Apoptosis and delayed degeneration after spinal cord injury in rats and monkeys. Nat Med. 1997;3:73–76. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GR, Jr, McClellan AD. Long distance axonal regeneration of identified lamprey reticulospinal neurons. Exp Neurol. 1994;127:94–105. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliagina TG, Zelenin PV, Fagerstedt P, Grillner S, Orlovsky GN. Activity of reticulospinal neurons during locomotion in the freely behaving lamprey. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:853–863. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dergham P, Ellezam B, Essagian C, et al. Rho signaling pathway targeted to promote spinal cord repair. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6570–6577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06570.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil CI, Winton MJ, McKerracher L. Rho activation patterns after spinal cord injury and the role of activated Rho in apoptosis in the central nervous system. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:233–243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy P, Schmandke A, Schmandke A, et al. Rho-associated kinase II (ROCKII) limits axonal growth after trauma within the adult mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15266–15276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4650-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellezam B, Dubreuil C, Winton M, et al. Inactivation of intracellular Rho to stimulate axon growth and regeneration. Prog Brain Res. 2002;137:371–380. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TA, Son YJ. Extrinsic and intrinsic determinants of nerve regeneration. J Tissue Eng. 2011;2:2041731411418392. doi: 10.1177/2041731411418392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D, Xing B, Dill J, et al. Leukocyte common antigen-related phosphatase is a functional receptor for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan axon growth inhibitors. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14051–14066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1737-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontainhas AM, Townes-Anderson E. RhoA inactivation prevents photoreceptor axon retraction in an in vitro model of acute retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:579–587. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier AE, Takizawa BT, Strittmatter SM. Rho kinase inhibition enhances axonal regeneration in the injured CNS. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1416–1423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01416.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Hue J, Li S. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs promote axon regeneration via RhoA inhibition. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4154–4164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4353-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G. Myosin II activity is required for severing-induced axon retraction in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2004;189:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, Black JA, Waxman SG. Primary cortical motor neurons undergo apoptosis after axotomizing spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2003;462:328–341. doi: 10.1002/cne.10733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis ER, 2nd, Lu P, Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. IGF-I gene delivery promotes corticospinal neuronal survival but not regeneration after adult CNS injury. Exp Neurol. 2009;215:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle JD, Ye JH. Survival of chronically-injured neurons can be prolonged by treatment with neurotrophic factors. Neuroscience. 1999;94:929–936. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Zhang G, Selzer ME. Activated caspase detection in living tissue combined with subsequent retrograde labeling, immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization in whole-mounted lamprey brains. J Neurosci Methods. 2013;220:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs AJ, Swain GP, Snedeker JA, et al. Recovery of neurofilament expression selectively in regenerating reticulospinal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5206–5220. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05206.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Brady-Kalnay SM, Bellamkonda RV. Modulation of Rho GTPase activity alleviates chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan-dependent inhibition of neurite extension. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:299–307. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin LQ, Zhang G, Jamison C, Jr, et al. Axon regeneration in the absence of growth cones: acceleration by cyclic AMP. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:295–312. doi: 10.1002/cne.22057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon BK, Liu J, Messerer C, et al. Survival and regeneration of rubrospinal neurons 1 year after spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3246–3251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052308899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M, Fournier A, Selles-Navarro I, et al. Inactivation of Rho signaling pathway promotes CNS axon regeneration. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7537–7547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07537.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XZ, Xu XM, Hu R, et al. Neuronal and glial apoptosis after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5395–5406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05395.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madura T, Yamashita T, Kubo T, et al. Activation of Rho in the injured axons following spinal cord injury. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:412–417. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier PP, Sierra A, Schwab JM, Henke-Fahle S, Mueller BK. The Rho/ROCK pathway mediates neurite growth-inhibitory activity associated with the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans of the CNS glial scar. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:319–330. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori F, Himes BT, Kowada M, Murray M, Tessler A. Fetal spinal cord transplants rescue some axotomized rubrospinal neurons from retrograde cell death in adult rats. Exp Neurol. 1997;143:45–60. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.6318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederost B, Oertle T, Fritsche J, McKinney RA, Bandtlow CE. Nogo-A and myelin-associated glycoprotein mediate neurite growth inhibition by antagonistic regulation of RhoA and Rac1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10368–10376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10368.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson JL, Sears-Kraxberger I, Strong MK, et al. Unexpected survival of neurons of origin of the pyramidal tract after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11516–11528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1433-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson JL, Strong MK, Steward O. A reassessment of whether cortical motor neurons die following spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:2852–2869. doi: 10.1002/cne.22661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikova LN, Novikov LN, Kellerth JO. Survival effects of BDNF and NT-3 on axotomized rubrospinal neurons depend on the temporal pattern of neurotrophin administration. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:776–780. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovainen CM. Physiological and anatomical studies on large neurons of central nervous system of the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus). I. Muller and Mauthner cells. J Neurophysiol. 1967;30:1000–1023. doi: 10.1152/jn.1967.30.5.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ME. Mechanisms of functional recovery and regeneration after spinal cord transection in larval sea lamprey. J Physiol. 1978;277:395–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman MI, Yumul RE, Laramore C, Selzer ME. Expression of the repulsive guidance molecule RGM and its receptor neogenin after spinal cord injury in sea lamprey. Exp Neurol. 2009;217:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman MI, Zhang G, Selzer ME. Delayed death of identified reticulospinal neurons after spinal cord injury in lampreys. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:269–282. doi: 10.1002/cne.21789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Zheng B, Tessier-Lavigne M. False resurrections: distinguishing regenerated from spared axons in the injured central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2003;459:1–8. doi: 10.1002/cne.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerton JE. Morpholino, siRNA, and S-DNA compared: impact of structure and mechanism of action on off-target effects and sequence specificity. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:651–660. doi: 10.2174/156802607780487740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain GP, Snedeker JA, Ayers J, Selzer ME. Cytoarchitecture of spinal-projecting neurons in the brain of the larval sea lamprey. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:194–210. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynski MH, Steward O. Concepts and methods for the study of axonal regeneration in the CNS. Neuron. 2012;74:777–791. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MR, Cohen MJ. Synaptic regeneration in identified neurons of the lamprey spinal cords. Science. 1979;206:344–347. doi: 10.1126/science.482943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HS, Selzer ME. Axonal regeneration in lamprey spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1135–1144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-06-01135.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiu G, He Z. Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:617–627. doi: 10.1038/nrn1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Hu J, Li S, Huang L, Selzer ME. Selective expression of CSPG receptors PTPsigma and LAR in poorly regenerating reticulospinal neurons of lamprey. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:2209–2229. doi: 10.1002/cne.23529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Jin LQ, Hu J, Rodemer W, Selzer ME. Antisense Morpholino Oligonucleotides Reduce Neurofilament Synthesis and Inhibit Axon Regeneration in Lamprey Reticulospinal Neurons. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Jin LQ, Sul JY, Haydon PG, Selzer ME. Live imaging of regenerating lamprey spinal axons. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005;19:46–57. doi: 10.1177/1545968305274577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.