Abstract

Patients with severe mental illnesses manifest substantial deficits in self-assessment of the abilities that impact everyday functioning. This study compares patients with schizophrenia to healthy individuals on their social cognitive performance, their assessment of that performance, and the convergence between performance and indicators of effort in solving tasks. Patients with schizophrenia (n=57) and healthy controls (HC; n=47) completed the Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Test (BLERT), a psychometrically sound assessment of emotion recognition. Participants rated their confidence in the accuracy of their responses after each item. Participants were instructed to respond as rapidly as possible without sacrificing accuracy; the time to complete each item was recorded. Patients with schizophrenia performed less accurately on the BLERT than HC. Both patients and HC were more confident on items that they correctly answered than for items with errors, with patients being less confident overall; there was no significant interaction for confidence between group and accuracy. HC demonstrated a more substantial adjustment of response time to task difficulty by taking considerably longer to solve items that they got wrong, whereas patients showed only a minimal adjustment. These results expand knowledge about both self-assessment of social cognitive performance and the ability to appraise difficulty and adjust effort to social cognitive task demands in patients with schizophrenia.

1. Introduction

People with schizophrenia often show limited awareness of illness and difficulties in the self-assessment of their abilities and illness status (Amador et al., 1994; Durand et al., 2015; Gould et al., 2015; Keefe et al., 2015). Mis-estimation of ability is not specific to severe mental illness; most healthy individuals often overestimate their abilities across many different functional situations (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). However, healthy individuals are typically able to use feedback to adjust their self-assessment and thus adjust their effort or opinions of their competence. People with schizophrenia have been reported to fail to adequately adjust their effort in response to situational demands and reinforcement structures (Reddy et al., 2015), which may be due to difficulties in evaluation of their own abilities or challenges in assessing the difficulty of environmental challenges.

Previous research has shown that self-reports of ability, across the domains of cognition and everyday functioning, do not correlate with either objective performance on cognitive and functional tasks (Durand et al., 2015) or informed clinicians’ reports of functioning (Sabbag et al., 2011) in individuals with schizophrenia. This impaired self-assessment ability is one of several features of the lack of insight, demonstrated in a growing body of literature (e.g. Amador et al., 1994; Medalia & Thysen, 2010; Siu et al., 2015). Impairment in self-assessment has the potential for bi-directional impact in that those with poor performance may not recognize it, and those with adequate skills may underestimate their abilities (Harvey & Pinkham, 2015). Perhaps most importantly, deficits in self-assessment have been shown to have a stronger association with impairments in everyday functioning than actual impairments in cognition and functional skills (Gould et al., 2015). These findings suggest that self-assessment may be an important treatment target and that examination of self-assessment in other domains may be fruitful. Given its strong relationship to social outcomes (Fett et al., 2011; Pinkham & Penn, 2006), social cognition is one such domain.

Relatively few studies have examined self-assessment of social cognitive abilities in schizophrenia; however, these studies conducted have revealed difficulties. Specifically, when identifying the emotions and mental states of others, individuals with schizophrenia are more likely both to be incorrect and to report higher confidence in their incorrect responses (Köther et al., 2012; Langdon et al., 2014; Moritz et al., 2012). Thus, individuals with schizophrenia seem to have difficulty determining when they are likely to have misjudged a social situation; this may negatively impact social interactions and may be due to challenges in estimating the level of difficulty of the social demands.

Poor self-assessment may also contribute to difficulties with judging the difficulty of environmental demands. A potential reason for reduced performance in functional tasks, both cognitive and social cognitive, could be problems in effort adjustment when faced with tasks of differential difficulty (Docx et al., 2015; Fervaha et al., 2013; Horan et al., 2015). If individuals are unable to understand their own strengths and weaknesses (i.e. impaired self-assessment), it may be more challenging to understand the true difficulty of a task. Thus, challenges in judging one’s one ability may lead to problems in determining whether increasing effort would be likely to achieve a greater chance of success.

This paper reports on self-assessment of social cognitive abilities in a sample of adult patients with schizophrenia and demographically similar healthy controls. Social cognition and corresponding confidence and adjustment of effort were measured using a modified version of the Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition test (BLERT; Bell et al., 1997; Bryson et al., 1997). In this modification we asked participants to solve problems as rapidly as possible without sacrificing accuracy. We also asked them to provide a confidence assessment regarding the accuracy of their solutions after each item. We hypothesized that patients with schizophrenia, compared to healthy controls, would: 1): manifest poorer overall accuracy; 2); show impaired self-assessment by manifesting lower convergence between performance and confidence; and 3): manifest a reduced ability to adjust effort to challenging stimuli, as indexed by similar response times for both correct and incorrect items.

Additionally, as a growing body of literature has identified depression as a moderator of self-evaluation, we examined the influence of depression by including it as a covariate in our analyses. Mild depression has been shown to correlate with more accurate self-assessment of cognitive abilities in people with schizophrenia (Bowie et al., 2007; Gould et al., 2015; Sabbag et al., 2012), consistent with previous research in healthy populations demonstrating that mild depression contributes to more accurate judgment (Dunning & Story, 1991) and that deflating feedback leads to increases in the accuracy of self-assessment. Finally, because of previous work that implicated negative symptoms in impairments in allocation of effort and self-assessment (e.g., Horan et al., 2015; Sabbag et al., 2012), we examined the associations between negative symptoms and social cognitive performance, confidence in performance, and the response times for correct and incorrect responses for the patients with schizophrenia.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were 57 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 47 healthy controls (HC) recruited from three study sites: The University of Texas at Dallas (UTD), the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (UM), and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). UTD participants were recruited from Metrocare Services, a nonprofit mental health services provider for Dallas County, TX, and other area clinics. UM recruitment took place at the Miami VA Medical Center and the Jackson Memorial Hospital-University of Miami Medical Center. UNC individuals were recruited from the Outreach and Support Intervention Services (OASIS) program and Caramore, a structured support program for individuals with severe mental illness. The present study is a part of the fourth phase of the SCOPE psychometric study, an evaluation of modifications of social cognitive tests (Pinkham et al., 2015); throughout this phase of the study, promising candidate measures were modified and pilot tested using smaller samples.

To be eligible, patients required a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Patients could not have any hospitalizations within the last two months and had to be on a stable medication regimen for a minimum of six weeks with no dose changes for a minimum of two weeks. HC were screened for history of psychopathology to ensure they did not meet criteria for any major DSM-IV Axis I or II disorders. Exclusion criteria for both groups included: 1) presence or history of pervasive developmental disorder or mental retardation (defined as IQ<70) by DSM-IV criteria, 2) presence or history of medical or neurological disorders that may affect brain function (e.g. seizures, CNS tumors, or loss of consciousness for 15 minutes or more), 3) presence of sensory limitation including visual (e.g. blindness, glaucoma, vision uncorrectable to 20/40) or hearing impairments that interfere with assessment, 4) no proficiency in English, 5) presence of substance abuse in the past month, and 6) presence of substance dependence not in remission for the past six months.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Diagnoses

Diagnoses were confirmed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998), a brief structured diagnostic interview, supplemented by the Psychosis Module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID; First et al., 2002).

2.2.2 Social Cognition

All participants completed a modified version of the Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Test (BLERT; Bell et al., 1997; Bryson et al., 1997). This task consists of 21 video clips of a male actor, providing dynamic facial, vocal-tonal, and upper-body movement cues and measures the ability to correctly identify seven emotional states: happiness, sadness, fear, disgust, surprise, anger, or no emotion. The original version of the BLERT has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Bell, Bryson & Lysaker, 1997; Pinkham et al. 2016). The task in the present study was modified in two ways from the standard administration. First, participants were instructed to respond as rapidly as possible without sacrificing accuracy, which could include responding prior to the offset of the video clip. Second, after identifying the expressed emotion, participants rated how confident they were that their response was correct on a scale from 0 (not at all confident) to 100 (extremely confident). Response time to answer each item was recorded from the start of the video clip to when the participant provided their answer. Participants could respond during or after the presentation of the video clip (most participants responded after the video clip finished). Due to varying run times for each item, the video clip run time was subtracted from the total response time (from the start of the video clip to the participant’s response) to yield an accurate participant response time. This method can yield negative values when the participant responded before the clip finished, thus a separate method of capturing accurate response time was examined in all analyses as a “back up” method: a proportion of total response time (inclusive of video clip run time) to video run time. Results did not change utilizing this “back up” method, thus results based on the first method will be reported. Response time was used as a proxy for effort allocation, with a longer response time indicative of more effort being exerted. For both response times and confidence ratings, means were calculated separately for correct and incorrect items.

2.2.3 Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptomology was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996), a 21-item self-report measure of severity of depression. Items are measured on a scale from 0 to 3. A total depression score was created summing the 21 items (0–63). A validity check was performed by examining the correlation between the PANSS depression item and self reported depression (r=.51, p<.001).

2.2.4 Negative Symptoms

All patients were rated with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987), a semi-structured interview measuring various symptoms of schizophrenia. Negative symptoms were defined using Marder & Chouinard (1997) empirically derived factor of 6 negative symptoms: blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, passive-apathetic social withdrawal, lack of spontaneity, motor retardation, and active social avoidance. These 6 symptoms were summed to generate a negative symptoms total score.

2.2.5 Rater training

Symptoms raters and diagnostic raters were trained to reliability using the established procedures at each site and were the same raters used in previous phases of SCOPE (e.g., Pinkham et al., 2015).

2.3 Statistical Approach

An independent-sample t-test was used to examine between-group demographic and depression differences as well as overall task accuracy. Subsequently, two repeated measures ANOVAs, one for confidence and one for response time, were then conducted with item type (correct vs. incorrect) as the within-subject variable and group as the between-subject variable. Given the evidence linking depression to accuracy of self-assessment, the ANOVAs were also repeated using depression as a covariate. Post hoc analyses examined within-group differences and effect sizes. Finally, negative symptoms and all other variables were examined for their relationships using Pearson Product-moment correlations in the patients with shizophrenia.

3. Results

Patients and HC did not differ in their gender, ethnicity, race, or age; however HC had significantly more years of education than patients. Patients also had significantly higher levels of depression. As anticipated, HC performed significantly better on the BLERT (M: 72.95% correct, SD: 14.63) than patients (M: 63.49% correct, SD: 20.88; t(102)=2.62, p=.01). Demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information about healthy controls and patients with schizophrenia

| Healthy controls (n=47) | Patients with schizophrenia (n=57) | Significance test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | χ2(2,N=104) = .28 | ||||

| Female | 19 | 40.4 | 26 | 45.6 | |

| Male | 28 | 59.6 | 31 | 54.4 | |

| Ethnicity | χ2(1,N=104) = 1.02 | ||||

| Hispanic | 13 | 27.7 | 11 | 19.3 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 34 | 72.3 | 46 | 80.7 | |

| Race | χ2(3,N=104) = 2.57 | ||||

| Caucasian | 17 | 36.2 | 20 | 35.1 | |

| African American | 28 | 59.6 | 32 | 56.1 | |

| Asian | 2 | 4.3 | 2 | 3.5 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Significance test | |

|

|

|||||

| Age | 42.62 | 9.61 | 43.02 | 10.23 | t(101) = −.20 |

| Education (years) | 14.44 | 1.85 | 12.99 | 2.46 | t(102) = 3.32** |

| Depression | 4.23 | 5.70 | 13.21 | 10.409 | t(102) = −5.29*** |

p < .05,

p<.01,

p<.001

3.1 Confidence

A group by item-type two-way repeated measures ANOVA on confidence ratings indicated a significant item-type main effect (F(1,102)=68.71, p<.001) such that overall, participants were more confident for correct items (M=85.49, SD=16.44), than for incorrect items (M=77.57, SD=18.22). There was also a significant main effect of group (F(1,102)=11.12, p=.001) such that HC were more confident overall (M=89.03, SD=14.75) than patients (M=78.26, SD=17.04). The group by item-type interaction was not significant (F(1,102)=.10, p=.757). When depression was added as a covariate to the model, the significant main effect of item-type remained (F(1,101)=43.29, p<.001), but the main effect of group was no longer significant (F(1,101)=3.32, p=.072), suggesting that depression influenced the level of confidence in self-assessments across diagnoses. The non-significant interaction was unchanged (F(1,101)=27.90, p=.44). Means are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Information on Confidence and Response Time

| Healthy Controls | Patients with Schizophrenia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | Correct | Incorrect | |

| Confidence1 | 91.06(14.90) | 83.46(16.74) | 80.90(16.35) | 72.71(18.10) |

| Response Time2 | 2.99(3.36) | 6.52(4.80) | 4.25(4.08) | 5.30(4.68) |

Measured on a 100-point scale

Time in seconds (measured by subtracting the video run time from the total time it took the participant to respond from start of video)

3.2. Response Time

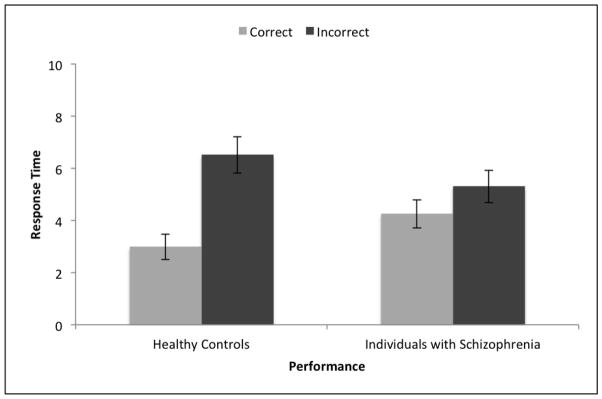

A group by item-type two-way repeated measures ANOVA on response time indicated a significant main effect of item-type (F(1,102)=57.298, p<.001) such that overall, participants took less time on correct items (M=3.68, SD=3.81) than on incorrect items (M=5.85, SD=4.75). The main effect of group was not significant (F(1,102)=.02, p=.981). Importantly, however, the interaction between item-type and group was significant F(1,102)=16.62, p<.001) indicating a larger difference in response times between correct and incorrect items for HC than for patients. This interaction effect is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Response Time and Performance.

Error bars represent one standard error above and below the mean.

When depression was added as a covariate to the model, the main effect of item-type (F(1,101)=29.59, p<.001), the main effect of group (F(1,101)=.15, p=.704), and the interaction effect (F(1,101)=57.95, p=.001) remained unchanged.

Post hoc paired-sample t-tests revealed that HC significantly differed in their response time for correct and incorrect responses (t(46)=−7.41, p<.001) as did patients (t(56)=−2.74, p=.008). According to Cohen’s guidelines (Cohen, 1988), the effect size for HC was very large (d=1.08), indicating a very large amount of variance in effort allocation for HC was due to item type (i.e., correct vs. incorrect). However, the effect size for patients was small to medium (d=.36) indicating that only a small to medium amount of variance in effort allocation for patients was due to item type. These effect sizes confirm that HC have a far greater magnitude of difference in response times for correct and incorrect items than patients. Means are provided in Table 2.

3.3. Correlations with Negative Symptoms

Pearson correlations between number of correct responses, confidence in correct and incorrect responses, and response times to correct and incorrect responses were calculated between total negative symptoms (mean=10.81; SD=3.82) and each of the 6 individual negative symptoms (blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, passive-apathetic social withdrawal, lack of spontaneity, motor retardation, and active social avoidance). None of the five performance items correlated with total negative symptoms, all r<.17, all p>.22. For the individual negative symptoms, there were two statistically significant correlations out of the correlations that were computed. More severe passive-apathetic social withdrawal correlated with more items identified correctly (r=.29, p=.029), and longer response times on incorrect items correlated with higher scores on motor retardation (r=.29, p=.026). These two correlations would not survive even liberal (p<.01) correction for multiple comparisons.

4. Discussion

This study was the first to compare patients with schizophrenia to healthy control (HC) participants on task performance, confidence in their performance, and effort allocation on a measure of social cognition. Effort allocation and confidence of patients and HC participants were examined across items that individuals responded to correctly and incorrectly. As expected, and as demonstrated in previous studies (Pinkham et al., 2015), HC participants performed significantly better on the social cognition measure. HC also showed more overall confidence than patients, and both patients and HC were more confident in their responses to items that were correct. Likewise both patients and HC expended more effort, as indexed by longer response times, on incorrect items. Importantly however, assuming that longer response times indicate greater effort, individuals with schizophrenia did not adjust their effort on challenging items to the same degree as healthy individuals. These results suggest that despite both patients and HC being able to recognize when an item was more challenging to them (as evidenced by differences in confidence for accurate and inaccurate responses), patients did not adjust their effort appropriately to task demands. This is consistent with previous literature showing deficits in social cognitive effort-based decision-making in individuals with schizophrenia (e.g., Green et al., 2015; Horan et al., 2015; Reddy et al., 2015) but expands upon these findings by being the first empirical report to evaluate effort allocation as well as confidence in patients with schizophrenia with respect to social cognitive abilities.

Consistent with this interpretation, overall response times for the patients were much less variable; they took more time to solve correct items and spent less time on incorrect items compared to healthy controls. Thus, in contrast to typical patterns of generalized slowing in performance, patients were only slower than healthy participants when they were correct. Patients were not slower even if it would have been more adaptive to do so, or even more reflective.

The results of the present study are somewhat contrary to previous studies of self-assessment of social cognition. Previous research has identified high rates of over-confidence of performance on social cognitive tasks in patients with schizophrenia (Köther et al., 2012; Moritz et al., 2012), whereas the results of this study indicate no differences in confidence between healthy and affected individuals. For example, Köther and colleagues (2012) found that patients with schizophrenia had higher levels of overconfidence for incorrect items compared to HC participants; their further analyses revealed that when comparing depressed patients to non-depressed patients and HC, there was no difference in regards to overconfidence or accuracy. The results of the present study did not find any significant overconfidence in individuals with schizophrenia in comparison to healthy individuals – overconfidence was also not found when accounting for all participants’ depression scores.

It is possible that covarying for depression for all participants – rather than dichotomizing patients only into depressed and non-depressed or not including depression in analyses at all – is key in understanding self-assessment in social cognition; this would be consistent with compelling findings that depression is linked to self-assessment of social cognition for both healthy and non-healthy individuals (Bowie et al., 2007; Dunning & Story, 1991 Gould et al., 2015; Harvey et al., in press;; Sabbag et al., 2012). Also worthy of note, previous research (Köther et al., 2012; Moritz et al., 2012) measured confidence differently in their samples (via a 4-point Likert scales with different anchors than the present study). This methodological difference could also impact the differences in findings between the present study and previous research on self-assessment of social cognition. Future research would do well to continue examining overconfidence in individuals with schizophrenia in regards to social cognition with various rigorous methodologies.

Negative symptoms had a minimal relationship with performance, confidence, and effort allocation. Symptom severity was quite mild and greater severity of negative symptoms might lead to larger correlations. However, these results demonstrate that problems in social cognitive accuracy and effort allocation are present even in patients with mild negative symptoms, and that failure to devote greater effort to difficult items may be more closely linked to inability rather than a lack of motivation.

This study indicates a potential mechanism for some of the impairments in social functioning in individuals with schizophrenia. Not only did they perform more poorly overall, which is not surprising given the evidence in the literature regarding social cognitive abilities in individuals with schizophrenia, but they also did not adjust their effort accordingly to social cognitive stimuli that were more challenging for them to solve. Further, impaired difficulty-based situational assessments could interact with negative symptoms, such as anhedonia and avolition, (Kopelowicz et al., 1997; Kurtz & Mueser, 2008). Previous literature has identified a pattern of impairment within schizophrenia called “deficit syndrome” (Carpenter et al., 1988) characterized by primarily negative symptoms (e.g., blunted affect, lack of motivation, anhedonia and avolition). Some of these impairments could interact with problems in identifying the level of challenge and subsequent likelihood of success when attempting real-world social interactions and everyday activities.

While this study is the first to examine effort allocation and social cognitive self-assessment, future work needs to explore the complex relationship and interaction between negative symptoms, depression, effort allocation and other factors potentially influencing social deficits. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and social skills training have the strongest evidence for reducing social deficits associated with schizophrenia (Elis et al., 2013). Previous studies have noted that reduced intrinsic motivation leads to poorer outcomes in effort-demanding interventions, such as cognitive remediation (Medalia & Choi, 2010). Given the results of the present work, future research should examine how effort allocation may moderate intrinsic motivation and hence potential treatment response. Such treatment efforts are already underway for neurocognition, with meta-cognition training being conducted by reseachers such as Lysaker and DiMaggio (2014).

A number of limitations should be considered. First, the sample was recruited from urban university settings; it is possible that findings do not generalize to the general population of adults with schizophrenia. Relatedly, to be eligible for the study, patients were required to be clinically stable. These criteria may exclude a large subset of individuals with schizophrenia and early course or recently hospitalized patients may perform differently. As noted above, symptom severity was generally quite mild.

In terms of other limitations, there were no specific rewards offered for correct performance, thus making it difficult to assume that the results are due to reward sensitivity as compared to general appraisal of task difficulty. Further, there are factors other than effort that could be determinants of the response times. These could include reduced motivation to perform well compared to healthy controls. The fact that patients were not generally slower than HC shows that their performance was not due to a global deficit in responding to stimuli. Although negative severity was modest, a targeted assessment of anhedonia was not part of the clinical assessment and future work could focus on this assessment.

Despite these limitations, the present study highlights impaired effort allocation as a potential contributor to social cognitive impairments in individuals with schizophrenia. That is, for patients, while some items are more difficult than others, as evidenced by reduced confidence when incorrect, they did not adjust the time spent on different items as much as HC. Importantly, this pattern was not related to negative symptoms, indicating that it is unlikely to be due to globally reduced motivation to devote more effort to harder items. Future work should focus on developing interventions that target appraisal of task difficult and effort-based decision-making and evaluate how effort allocation may respond to high-quality evidence-based care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Green for his extensive assistance with earlier versions of this manuscript. All other contributors to this paper are listed as authors.

Role of Funding Source.

This study was sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. The sponsor was not involved in the study design and collection of data.

Footnotes

Contributors.

Drs. Harvey, Penn, and Pinkham contributed to the design of this study. Ms. Cornacchio undertook the statistical analysis and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. No medical writers worked on this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest.

Dr. Harvey serves as a consultant/advisory board member for Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Otsuka Digital Health, Sanofi, Sunovion, and Takeda.

The other authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Clark SC, Gorman JM. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1994;51(10):826–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950100074007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. p. b9. [Google Scholar]

- Bell M, Bryson G, Lysaker P. Positive and negative affect recognition in schizophrenia: A comparison with substance abuse and normal control subjects. Psychiat Res. 1997;73(1–2):73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Twamley EW, Anderson H, Halpern B, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Self-assessment of functional status in schizophrenia. J Psychiat Res. 2007;41(12):1012–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson G, Bell M, Lysaker P. Affect recognition in schizophrenia: A function of global impairment or a specific cognitive deficit. Psychiat Res. 1997;71(2):105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AM. Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: The concept. Am J Psychiat. 1988;145(5):578–583. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. New Jersey: Lawrence Erl-baum Associates; 1988. The effect size index: d; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Docx L, de la Asuncion J, Sabbe B, Hoste L, Baeten R, Warnaerts N, Morrens M. Effort discounting and its association with negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2015;20(2):172–185. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2014.993463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D, Story AL. Depression, realism, and the overconfidence effect: Are the sadder wiser when predicting future actions and events? J Per Soc Psychol. 1991;61(4):521. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand D, Strassnig M, Sabbag S, Gould F, Twamley EW, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Factors influencing self-assessment of cognition and functioning in schizophrenia: Implications for treatment studies. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2015;25(2):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elis O, Caponigro JM, Kring AM. Psychosocial treatments for negative symptoms in schizophrenia: current practices and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(8):914–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fervaha G, Graff-Guerrero A, Zakzanis KK, Foussias G, Agid O, Remington G. Incentive motivation deficits in schizophrenia reflect effort computation impairments during cost-benefit decision-making. J Psychiat Res. 2013;47(11):1590–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fett AJ, Viechtbauer W, Dominguez M, Penn DL, van Os J, Krabbendam L. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav R. 2011;35(3):573–588. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gould F, McGuire LS, Durand D, Sabbag S, Larrauri C, Patterson TL, … Harvey PD. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: Accuracy of evaluation of cognition and everyday functioning. Neuropsychology. 2015;29(5):675–682. doi: 10.1037/neu0000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Horan WP, Barch DM, Gold JM. Effort-based decision making: a novel approach for assessing motivation in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 2015;41(5):1035–1044. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Pinkham A. Impaired self-assessment in schizophrenia: Why patients misjudge their cognition and functioning: Observations from caregivers and clinicians seem to have the most validity. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(4):53. [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Reddy LF, Barch DM, Buchanan RW, Dunayevich E, Gold JM, … Green MF. Effort-based decision-making paradigms for clinical trials in schizophrenia: Part 2-external validity and correlates. Schizophrenia Bull. 2015;41(5):1055–1065. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opfer LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 1987;13(2):261. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Davis VG, Spagnola NB, Hilt D, Dgetluck N, Ruse S, … Harvey PD. Reliability, validity and treatment sensitivity of the Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2015;25(2):176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Mintz J, Zarate R. Comparison of efficacy of social skills training for deficit and nondeficit negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiat. 1997;154(3):424. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köther U, Veckenstedt R, Vitzthum F, Roesch-Ely D, Pfueller U, Scheu F, Moritz S. “Don’t give me that look”—Overconfidence in false mental state perception in schizophrenia. Psychiat Res. 2012;196(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of controlled research on social skills training for schizophrenia. J Consult Clin Psych. 2008;76(3):491. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon R, Connors MH, Connaughton E. Social cognition and social judgment in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. 2014;1(4):171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Dimaggio G. Metacognitive capacities for reflection in schizophrenia: Implications for developing treatments. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40:487–491. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder SR, Chouinard G. The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiat. 1997;58(12):1–478. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Choi J. Motivational enhancements in schizophrenia. In: Roder V, Medalia A, editors. Neurocognition and Social Cognition in Schizophrenia Patients. Vol. 177. 2010. pp. 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Thysen J. A comparison of insight into clinical symptoms versus insight into neuro-cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr res. 2010;118(1):134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz S, Woznica A, Andreou C, Köther U. Response confidence for emotion perception in schizophrenia using a Continuous Facial Sequence Task. Psychiat Res. 2012;200(2):202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Penn DL. Neurocognitive and social cognitive predictors of interpersonal skill in schizophrenia. Psychiat Res. 2006;143(2):167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Green MF, Harvey PD. Social cognition psychometric evaluation: Results of the initial psychometric study. Schizophrenia Bull. 2015:sbv056. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy LF, Horan WP, Barch DM, Buchanan RW, Dunayevich E, Gold JM, … Young JW. Effort-based decision-making paradigms for clinical trials in schizophrenia: part 1—psychometric characteristics of 5 paradigms. Schizophrenia Bull. 2015:sbv089. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbag S, Twamley EM, Vella L, Heaton RK, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Assessing everyday functioning in schizophrenia: not all informants seem equally informative. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1):250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, … Dunbar GC. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiat. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu CO, Harvey PD, Agid O, Waye M, Brambilla C, Choi W, Remington G. Insight and subjective measures of quality of life in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. 2015;2(3):127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]