Abstract

Background

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a type of ANCA-associated vasculitis associated with severe end-organ damage and treatment-related complications that often lead to hospitalization and death. Nationwide trends in hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality over the past two decades are unknown and were evaluated in this study.

Methods

Using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest all-payer inpatient database in the US, the trends in hospitalizations with a discharge diagnosis of GPA (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis; ICD-9-CM: 446.4) between 1993 and 2011 were studied. Analyses were performed using hospital-level sampling weights to obtain US national estimates.

Results

From 1993 to 2011, the annual hospitalization rate for patients with a principal diagnosis of GPA increased by 24% from 5.1 to 6.3/1,000,000 US persons (P-for-trend<0.0001); however, their in-hospital deaths declined by 73% from 9.1% to 2.5% (P-for-trend<0.0001), resulting in a net 66% reduction of the annual in-hospital mortality rate. The median length of stay declined by 20% from 6.9 days in 1993 to 5.5 days in 2011 (P-for-trend=0.0002). Infection was the most common principal discharge diagnosis when GPA was a secondary diagnosis, including among those who died during hospitalization.

Conclusion

The findings from these nationally representative, contemporary, inpatient data indicate that in-hospital mortality of GPA has declined substantially over the past two decades while the overall hospitalization rate for GPA increased slightly. Infection remains a common principal hospitalization diagnosis among GPA patients, including hospitalizations resulting in mortality.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis) is a type of ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) responsible for necrotizing inflammation in potentially any organ system, and is thus, associated with severe end-organ damage and treatment-related complications that often lead to hospitalization and death (1–3). Over the last several decades, the landscape of GPA management has changed. Recognition of cyclophosphamide as an effective treatment in the 1980s (4) transformed this condition from one associated with a high risk of mortality to one better characterized as a chronic illness. Subsequent evidence-based shifts in the management of GPA have led to glucocorticoid (GC)- and cyclophosphamide-sparing regimens intended to minimize the risk of therapy-related complications while maintaining survival gains(5). During this period, advances in the management of renal failure(6), severe sepsis(7), and other complications of GPA have also been made. The benefits of these trends in the management of GPA and its complications have been affirmed in a recent UK general population study which demonstrated that all-cause mortality improved considerably over the last two decades(8).

A previous study of hospitalizations for GPA in the US found that the in-hospital mortality rate was 10% between 1986 and 1990(1). Since this early report, no contemporary data are available regarding how shifts in the management of GPA and associated complications have affected hospitalization trends and in-hospital mortality. These data serve as important benchmarks for overall GPA care. In this study, recent nationwide trends in hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality over the past two decades were evaluated.

METHODS

Data Source

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) which is the largest, publically-available all-payer inpatient database in the US, including patients covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, as well as the uninsured was used to conduct this study. It was created by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and includes data and sampling weights from over 1,000 hospitals across 44 states (representing over 97% of the US population). The NIS represents a 20% stratified probability sample of US hospitals (all non-federal, short-term, general, and other specialty hospitals, excluding hospital units of institutions). Hospitals are divided into strata based on five characteristics: ownership/control, bed size, teaching status, urban/rural location, and U.S. region. The NIS undergoes annual data quality assessments to ensure the internal validity of the database. Because the data are publically available and contain no patient identifiers, this study is exempt from IRB approval. Prior studies in medicine, including rheumatic diseases, have used the NIS to investigate national hospitalization trends(9).

Study Design

Temporal hospitalization trends for GPA were studied using data from the 1993–2011 releases of the NIS. All patients who were hospitalized during the study period for GPA (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code: 446.4) were included(1). To capture hospitalization rates and mortality trends, principal discharge diagnoses were used to maximize the validity of the case definition(9). In-hospital GPA mortality trends were compared to overall inpatient mortality trends in the US. Data pertaining to individual demographic features (e.g., sex, age, ethnicity, and insurance status) and other hospitalization characteristics (e.g., length of stay) were also collected from the NIS.

For comorbidities associated with GPA hospitalizations, the AHRQ Clinical Classification Software (CCS) was used to organize primary diagnoses into a relatively small number of major, mutually-exclusive diagnostic categories. For example, infection is a CCS category (CCS category 1) that includes bacterial, mycotic, viral, and parasitic infections; however, certain organ-specific infections are included within other CCS categories. These other categories included 6.1: Central nervous system infection; 8.1: Respiratory infection; 9.1: Intestinal infection; 9.6.4.2: Diverticulitis; 9.6.6: Peritonitis and intestinal abscess; 10.1.4: Urinary tract infections; 12.1: Skin and subcutaneous tissue infections; 13.1: Infective arthritis and osteomyelitis; and 16.10.1.2: Infection of internal prosthetic device. All infection diagnostic categories were combined to determine the proportion of hospitalizations for infection.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using hospital-level sampling weights provided by the NIS to obtain US national estimates. Annual population rates of hospitalizations (per 1,000,000 US persons) for GPA were calculated based on the projected number of hospitalizations and US census population for each year (1993 through 2011). Annual trends in hospitalization rates, principal diagnoses, and in-hospital mortality over time were assessed using Poisson regression models that included a variable representing the linear trend from the baseline year of 1993; a similar analysis was conducted for length of stay with linear regression. Hospitalization trends by subgroup, including age (<64 and ≥65 years old) and sex were also examined. All p-values were 2-sided with a significance threshold of p <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) except for the trend in length of stay (nonparametric) which was analyzed using the ‘nptrend’ command in Stata (Stata12; StataCorp, College Station, Tex)

RESULTS

Demographic Features of GPA Hospitalizations

From 1993 to 2011, there were 30,485 hospitalizations with a principal discharge diagnosis of GPA (Table 1). Over the study period, the average age of hospitalized GPA patients tended to decline from 55.4 (±1.3) years to 52.8 (±1.4) years (Table 1). Coincident with this, the proportion of patients over the age of 65 slightly declined from 36.3% (±4.3) to 33.9% (±3.0). The sex distribution remained stable (50.3% [±3.8] male in 1993 and 50.3% [±2.9] in 2011) Table 1. Throughout the study period, the majority of patients were white, and Medicare and private insurance were the most common primary payers.

Table 1.

Demographics, Trends, Mortality, and Length of Stay of Hospitalizations with a Principal Diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, 1993–2011

| Year | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations (N) | 1315 | 1419 | 1251 | 1258 | 1246 | 1290 | 1293 | 1474 | 1697 | 1576 | 1686 | 1638 | 1988 | 1668 | 1499 | 1964 | 2128 | 2120 | 1978 | |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean (yrs) | 55.4 | 57.0 | 57.6 | 56.4 | 55.8 | 55.7 | 55.7 | 54.3 | 55.5 | 55.4 | 53.7 | 54.3 | 53.8 | 52.6 | 52.9 | 54.7 | 53.9 | 51.6 | 52.8 | |

| <65 years (%) | 63.7 | 61.6 | 56.0 | 55.1 | 61.2 | 64.5 | 62.2 | 63.0 | 60.9 | 65.3 | 66.2 | 65.3 | 63.3 | 69.6 | 67.0 | 66.8 | 66.0 | 71.0 | 66.1 | |

| ≥65 years (%) | 36.3 | 38.4 | 44.0 | 44.9 | 38.8 | 35.5 | 37.8 | 37.0 | 39.1 | 34.7 | 33.8 | 34.7 | 36.7 | 30.4 | 33.0 | 33.2 | 34.0 | 29.0 | 33.9 | |

| Sex (%) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 50.3 | 48.2 | 47.5 | 53.4 | 50.3 | 48.7 | 50.7 | 48.8 | 39.8 | 38.7 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 48.3 | 51.1 | 47.0 | 50.9 | 50.9 | 51.1 | 50.3 | |

| Female | 49.7 | 51.8 | 52.5 | 46.6 | 49.7 | 51.3 | 49.3 | 51.2 | 60.2 | 61.3 | 54.4 | 54.4 | 51.7 | 48.9 | 53.0 | 49.1 | 49.1 | 48.9 | 49.7 | |

| Ethnicity (%)* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| White | 70.1 | 71.2 | 75.2 | 71.2 | 73.7 | 62.7 | 64.1 | 60.4 | 62.7 | 53.0 | 54.1 | 64.9 | 53.5 | 56.2 | 51.5 | 60.5 | 55.3 | 63.8 | 69.6 | |

| Non-White | 10.4 | 7.3 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 14.5 | 14.0 | 13.6 | 17.0 | 14.8 | 17.3 | 18.1 | 19.7 | 20.4 | 20.3 | 25.1 | 25.0 | |

| Primary Payer (%) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Medicare | 35.6 | 40.3 | 42.4 | 39.7 | 41 | 42.4 | 43.2 | 41.4 | 43.4 | 40.8 | 37.5 | 39.1 | 43.2 | 38.1 | 42.7 | 34.2 | 34.2 | 36.1 | 40.7 | |

| Medicaid | 6.6 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 11.0 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 5.3 | 12.0 | 11.6 | 9.1 | 13.2 | 10.6 | |

| Private | 51.9 | 50.4 | 46.3 | 47.3 | 45.9 | 46.4 | 42.1 | 44.4 | 44.1 | 42.3 | 44.3 | 42.7 | 41.1 | 44.1 | 38.2 | 45.9 | 49.3 | 40.8 | 38.7 | |

| Hospitalization Rate (/1,000,000) | 5.1 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.3 | <0.0001 |

| <65 years old | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 4.8 | <0.0001 |

| ≥65 years old | 14.5 | 16.4 | 16.4 | 16.6 | 14.0 | 13.3 | 14.1 | 15.5 | 18.8 | 15.4 | 15.9 | 15.8 | 19.9 | 13.7 | 13.1 | 16.8 | 18.3 | 15.2 | 16.2 | 0.049 |

| Male | 5.3 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 6.5 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 5.0 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 7.0 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.2 | <0.0001 |

| Deaths During Hospitalization (N) | 119 | 115 | 107 | 95 | 95 | 74 | 75 | 84 | 126 | 102 | 79 | 104 | 132 | 75 | 58 | 42 | 67 | 79 | 49 | |

| Hospital Mortality Rate (%) | 9.1 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 4.7 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 2.5 | <0.0001 |

| Median Length of Stay (days) | 6.9 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 0.001 |

The total does not equal 100% since race was unavailable in certain states during certain years.

Trends in Hospitalization Rates

Over the study period, the annual hospitalization rate when GPA was the primary diagnosis increased by 24% from 5.1 to 6.3/1,000,000 US persons (P<0.0001) (Table 1). This trend persisted among subgroups by age and sex (all p-values <0.05) (Table 1).

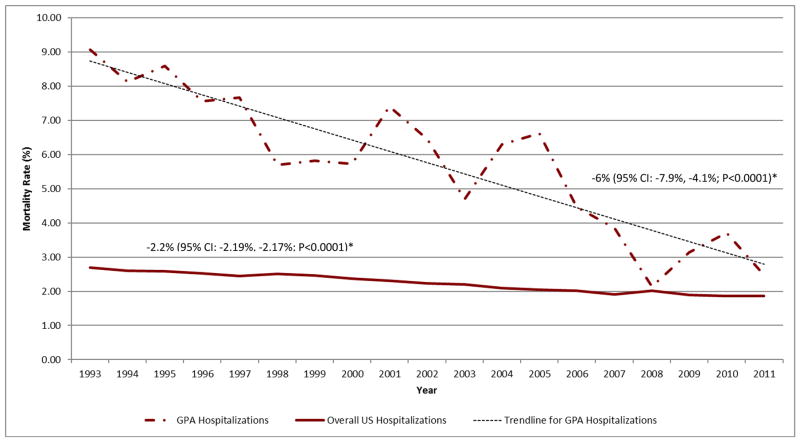

Trends in In-Hospital Mortality

Of the 30,485 GPA hospitalizations, 1,676 (5.4%) resulted in death. The annual mortality rate declined by 73% from 9.1% in 1993 to 2.5% in 2011 (P-for-trend<0.0001) (Figure 1 and Table 1). When accounting for the increase in hospitalization rate, the net reduction in the annual in-hospital mortality rate was 66%. These improvements were significantly greater than that of the mortality rate for all US hospitalizations which declined by 30% from 2.7% to 1.9% during the same period (P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Mortality in Hospitalizations with a Principal Diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA) Compared to All US Hospitalizations 1993–2011

*Mortality rate change per year

In a sensitivity analysis (see Supplementary Material) to evaluate the potential effect of multiple hospitalizations for the same patient in a given year, we excluded subsequent hospitalizations in the same year if the identical age, sex, race, income, health insurance, and hospital identification code were present. In this analysis, there was no significant difference in annual mortality rates when 595 hospitalizations were excluded.

Trends in Length of Stay

There was a significant decline in the length of stay among those with a principal diagnosis of GPA during the study period. The median length of stay declined by 20% from 6.9 days in 1993 to 5.5 days in 2011 (P-for-trend=0.001) (Table 1). In comparison, the length of stay for overall US hospitalizations did not decline significantly during this period (P-for-trend=0.6).

Principal Reasons for Hospitalization among GPA Patients

To explore common reasons for hospitalization, the principal diagnosis when GPA was listed as a secondary diagnosis (N=133,035 hospitalizations) was determined. As discussed, CCS software permits one to group principal diagnoses into mutually exclusive categories. When GPA was listed as the secondary diagnosis, the most frequent principal discharge diagnoses were infections, which accounted for over 24% of the primary diagnoses when GPA was the secondary diagnosis (Table 2); the majority of infections were respiratory infections, especially pneumonia. During the study period, there was no significant change in the proportion of admissions for infection (P-for-trend=0.97). Circulatory system conditions and non-infectious respiratory system conditions accounted for 21% and 11% of hospitalizations, respectively (Table 2). There was a significant decline in the proportion of admissions in which neoplasm (P-for-trend <0.0001), cardiovascular disease (P-for-trend=0.02), nephritis (P-for-trend<0.001), or chronic kidney disease (P-for-trend<0.0001) were the principal diagnosis. There was a rise in the proportion of admissions for acute kidney injury (P-for-trend 0.04).

Table 2.

Top Principal Discharge Diagnoses for Hospitalizations with a Secondary Diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

| Principal Diagnosis | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | P-for- Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Secondary GPA Hospitalizations | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Total Infection | 31.0% | 27.3% | 27.5% | 26.3% | 26.0% | 22.1% | 21.6% | 23.6% | 23.4% | 23.1% | 23.1% | 21.5% | 24.4% | 22.7% | 27.2% | 24.2% | 26.9% | 24.6% | 26.6% | 0.97 |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 6.1% | 6.6% | 6.3% | 6.0% | 5.7% | 4.5% | 3.5% | 4.8% | 4.4% | 3.8% | 4.1% | 4.8% | 5.5% | 6.5% | 6.6% | 6.3% | 7.4% | 6.8% | 8.2% | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory infection | 16.4% | 11.3% | 14.1% | 14.0% | 14.1% | 10.3% | 11.7% | 11.9% | 10.9% | 11.4% | 10.7% | 9.3% | 11.9% | 9.0% | 11.8% | 10.3% | 10.6% | 9.6% | 10.2% | <0.0001 |

| Diseases of Respiratory System (Including Infection) | 23.9% | 20.8% | 25% | 23.4% | 24.7% | 18.4% | 20.0% | 21.9% | 21.5% | 22.1% | 21.0% | 20.5% | 24.2% | 21.5% | 22.7% | 22.9% | 21.3% | 20.2% | 22.7% | 0.6 |

| Neoplasm | 4.6% | 3.5% | 3.8% | 5.5% | 2.5% | 4.4% | 3.7% | 4.1% | 3.6% | 4.1% | 3.5% | 2.7% | 3.9% | 2.4% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 2.8% | 2.6% | 2.7% | <0.0001 |

| Cancer of Urinary Organs | 0.9% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.4 |

| Diseases of the Circulatory System | 21.2% | 22.8% | 20.1% | 19.1% | 21.3% | 23.4% | 24.6% | 24.0% | 20.3% | 20.7% | 22.3% | 21.4% | 22.6% | 21.3% | 17.9% | 18.9% | 21.6% | 22.1% | 19.0% | 0.02 |

| Cardiac Diseases | 11.8% | 12.9% | 10.7% | 10.6% | 12.8% | 13.6% | 12.0% | 12.9% | 11.5% | 12.4% | 13.1% | 13.0% | 13.0% | 12.5% | 10.1% | 11.3% | 12.6% | 12.4% | 11.2% | 0.5 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 1.1% | 2.4% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 2.2% | 2.7% | 3.1% | 2.9% | 2.3% | 1.8% | 1.7% | 2.4% | 2.6% | 1.8% | 2.3% | 1.6% | 1.8% | 2.2% | 2.1% | 0.9 |

| Diseases of arteries and capillaries | 3.0% | 2.7% | 3.0% | 2.2% | 2.6% | 2.4% | 3.5% | 2.9% | 2.3% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 2.1% | 2.5% | 2.0% | 2.1% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.2% | 0.16 |

| Nephritis, Nephrosis, renal sclerosis | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.001 |

| Acute and unspecified renal failure | 2.8% | 4.4% | 4.4% | 3.8% | 3.7% | 2.7% | 4.0% | 3.7% | 4.2% | 3.1% | 4.4% | 5.0% | 5.3% | 4.9% | 5.3% | 4.4% | 3.7% | 4.5% | 4.1% | 0.037 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 2.3% | 2.7% | 3.0% | 2.9% | 1.8% | 1.7% | 2.6% | 2.4% | 1.7% | 1.7% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.6% | <0.0001 |

| All Fatal Secondary GPA Hospitalizations | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Total Infection | 45.9% | 39.6% | 38.7% | 35.1% | 38.8% | 30.6% | 32.2% | 33.8% | 27.3% | 36.8% | 31.1% | 26.5% | 35.4% | 35.6% | 37.6% | 46.7% | 48.6% | 44.3% | 41.5% | 0.2 |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 10.8% | 17.0% | 9.7% | 9.1% | 16.3% | 6.5% | 3.4% | 10.8% | 8.1% | 12.6% | 5.6% | 9.6% | 24.4% | 17.3% | 20.8% | 22.8% | 27.6% | 30.0% | 25.5% | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory infection | 33.8% | 20.8% | 22.6% | 20.8% | 20.0% | 17.7% | 24.1% | 18.9% | 13.1% | 18.4% | 20.0% | 12.0% | 7.3% | 15.4% | 11.9% | 17.4% | 10.5% | 11.4% | 11.7% | <0.0001 |

| Diseases of Respiratory System (Including Infection) | 37.8% | 32.1% | 43.5% | 45.5% | 46.3% | 35.5% | 41.4% | 40.5% | 38.4% | 28.7% | 36.7% | 32.5% | 25.6% | 31.7% | 30.7% | 37.0% | 23.8% | 30.0% | 26.6% | 0.02 |

| Neoplasm | 6.8% | 7.5% | 3.2% | 9.1% | 2.5% | 6.5% | 6.9% | 4.1% | 6.1% | 5.7% | 5.6% | 9.6% | 4.9% | 4.8% | 3.0% | 2.2% | 2.9% | 2.9% | 4.3% | 0.07 |

| Cancer of Urinary Organs | 1.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.8 |

| Diseases of the Circulatory System | 18.9% | 22.6% | 11.3% | 14.3% | 12.5% | 21.0% | 25.3% | 24.3% | 19.2% | 26.4% | 24.4% | 20.5% | 22.0% | 22.1% | 14.9% | 14.1% | 17.1% | 17.1% | 23.4% | 0.8 |

| Cardiac Diseases | 10.8% | 11.3% | 6.5% | 11.7% | 7.5% | 8.1% | 11.5% | 10.8% | 11.1% | 16.1% | 10.0% | 13.3% | 11.0% | 12.5% | 8.9% | 6.5% | 8.6% | 11.4% | 14.9% | 0.7 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 4.1% | 9.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 4.8% | 4.6% | 5.4% | 4.0% | 5.7% | 5.6% | 1.2% | 3.7% | 1.9% | 1.0% | 4.3% | 5.7% | 2.9% | 3.2% | 0.9 |

| Diseases of arteries and capillaries | 0.0% | 1.9% | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 6.5% | 6.9% | 4.1% | 3.0% | 2.3% | 5.6% | 3.6% | 2.4% | 4.8% | 2.0% | 2.2% | 2.9% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 0.8 |

| Nephritis, Nephrosis, renal sclerosis | 0.0% | 1.9% | 1.6% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.3 |

| Acute and unspecified renal failure | 6.8% | 0.0% | 6.5% | 3.9% | 3.8% | 1.6% | 2.3% | 4.1% | 4.0% | 3.4% | 6.7% | 8.4% | 6.1% | 4.8% | 8.9% | 7.6% | 5.7% | 7.1% | 6.4% | 0.04 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 2.7% | 5.7% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.006 |

Similarly, among those who died during their hospitalization when GPA was listed as a secondary diagnosis (Table 2), the most common principal discharge diagnosis was infection (31%), especially respiratory infection (16.4% of all in-hospital mortality cases). Over the study period there was no significant change in the rate of infection (P=0.2). Cardiovascular disease was the principal diagnosis in 19.6% of hospitalizations, and this did not change significantly over the study period (P=0.8). Renal failure, including acute renal failure and chronic kidney disease, was the principal discharge diagnosis in 6.4% of all fatal hospitalizations when GPA was a secondary diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

These findings, based on nationally representative, contemporary, inpatient data, indicate that in-hospital mortality of GPA has declined substantially over a 19-year period in the US, while the overall hospitalization rate for GPA increased slightly. The net reduction in in-hospital mortality among GPA patients was 66%, and the decline in in-hospital mortality was more than two-fold higher than that of all US hospitalizations. This affirms the results of a recent general population study that demonstrated a significant improvement in the mortality rate among GPA patients over a similar time period(8).

Only one previous study has evaluated national hospitalization trends in patients with GPA between 1986 and 1990(1), which is several years before the first year of our study. Interestingly, that study reported that 10% of GPA hospitalizations ended in death, which agrees well with the current study’s early findings. The majority of patients in the study by Cotch, et al were Caucasian (similar to ours), and there was a slight predominance of women. In contrast, in this contemporary cohort a greater proportion of hospitalized patients were over 65 years of age than was observed by Cotch et al., further supporting the hypothesis of improved survival over the recent years.

This mortality decline is encouraging and its explanation is likely multifactorial, related to evolving management strategies, secular trends, and the expanding availability of improved diagnostic tools. Over the last two decades, GPA management has shifted towards regimens that emphasize less cumulative GC and cyclophosphamide exposure in favor of conventional GC-sparing agents (e.g., azathioprine) and, most recently, rituximab(5, 10). These trends may have led to fewer severe complications of GC and cyclophosphamide, such as infection, which often lead to death(2).

While the rate of hospitalizations for a principal diagnosis of GPA increased during the study period, this increase was rather small compared to the in-patient mortality decline and might reflect the increasing prevalence of GPA in the setting of improved survival (8) and/or improved diagnostics with the spreading availability of ANCA testing.

These findings also indicate that there was no significant change in the hospitalization rate for GPA patients with a principal diagnosis of infection over the study period. The majority of infections reported in each year of the study involved the respiratory tract. The observed decline in the rate of respiratory infection is likely related to temporal trends in diagnostic coding given the stability of the overall infection rate as well as the increase in the rate of diagnoses for infectious and parasitic diseases which include sepsis(11). Similarly, among those with a secondary diagnosis of GPA who died during the study period, infection was also the most common principal diagnosis and there was no significant change in this observation over the study period. These observations suggest that infection is an important cause of death among patients with GPA, which has been suggested in a previous general population study(2) and a recent cohort study(12). Improvements in the management of infectious complications may be contributing to the observed improvements in GPA in-hospital survival; efforts to reduce infectious complications may prevent hospitalizations and are likely to further reduce mortality in GPA patients. Significant decreases in the proportion of admissions for nephritis, chronic kidney disease, neoplasm, and cardiovascular disease suggest that trends in the management of GPA have had an impact on these outcomes. These require confirmation in future studies.

Several strengths of this study deserve comment. The NIS database is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the US, representative of hospitalizations of the general population. Therefore, the overall hospitalization trends reported here are not affected by certain payment types or regional or practice variation, thus providing real-world data without a potential selection bias associated with non-population-based studies including clinical trials. Further, this study spanned nearly two decades, which covered major shifts in the management of GPA and related complications.

Nevertheless, there are potential limitations to this study. Because the NIS database is an administrative database, certain levels of misclassification of diagnostic codes are inevitable, similar to the previous study’s nationwide data source(1). However, GPA case definitions for hospitalization and mortality trends were limited to principal discharge diagnoses, which have been shown to substantially improve the validity of the case definition and thus minimize misclassification bias(13, 14). Similarly, there may have been cases of GPA which were coded under alternative ICD-9 code(s)(15). NIS data is de-identified so the unit of analysis is each hospitalization; as such, one cannot rule out the possibility that the observed mortality reductions are a reflection of multiple, shorter hospitalizations in a given year for the same patient who ultimately dies. In a sensitivity analysis, we found no significant difference in our results after excluding suspected re-hospitalizations. Due to the lack of disease-relevant details and medications administered, the severity of GPA or treatments administered for GPA could not be investigated as potential explanatory factors. Despite these potential limitations, the overall in-hospital mortality trends are critically important in their own right.

In summary, this is the first contemporary study to evaluate nationwide hospitalization trends among patients with GPA. In-hospital mortality significantly declined from 1993 to 2011, suggesting that trends specific to the management of GPA and its complications have been successful. Despite these advances, infections remain a frequent reason for hospitalization, including those who die during the hospitalization. Future studies may further investigate factors responsible for the improvements in mortality and the specific etiologies of infection in these patients to better guide preventative interventions.

Supplementary Material

Significance and Innovation.

This is the first study in over twenty years to evaluate hospitalization trends related to granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

In-hospital mortality related to granulomatosis with polyangiitis has declined significantly over the last two decades.

The frequency of infections as a reason for admission has remained stable over the last two decades

Infections are the most common reason for admission during hospitalizations ending in death, suggesting that further efforts to prevent infections in this condition may further improve survival.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no relevant financial disclosures to report with regard to the current manuscript.

Bibliography

- 1.Cotch MF, Hoffman GS, Yerg DE, Kaufman GI, Targonski P, Kaslow RA. The epidemiology of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Estimates of the five-year period prevalence, annual mortality, and geographic disease distribution from population-based data sources. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 Jan;39(1):87–92. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luqmani R, Suppiah R, Edwards CJ, Phillip R, Maskell J, Culliford D, et al. Mortality in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a bimodal pattern. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011 Apr;50(4):697–702. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan MD, Turnbull J, Selamet U, Kaur-Hayer M, Nightingale P, Ferro CJ, et al. Increased incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides: a matched-pair cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Nov;60(11):3493–500. doi: 10.1002/art.24957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, Hallahan CW, Lebovics RS, Travis WD, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Mar 15;116(6):488–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langford CA. Wegener’s granulomatosis: current and upcoming therapies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5(4):180–91. doi: 10.1186/ar771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Himmelfarb J. Continuous renal replacement therapy in the treatment of acute renal failure: critical assessment is required. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Mar;2(2):385–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02890806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A, Kaleekal T, Tarima S, McGinley E, et al. Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000–2007) Chest. 2011 Nov;140(5):1223–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace ZS, Lu N, Unizony S, Stone JH, Choi HK. Improved survival in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: A general population-based study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016 Feb;45(4):483–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim S, Lu N, Oza A, Fisher M, Rai S, Menendez M, et al. Trends in Gout and Rheumatoid Arthritis Hospitalizations in the United States, 1993–2011. JAMA. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3517. In PRess. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, Seo P, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 15;363(3):221–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003–2009. JAMA. 2012 Apr 4;307(13):1405–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGregor JG, Negrete-Lopez R, Poulton CJ, Kidd JM, Katsanos SL, Goetz L, et al. Adverse events and infectious burden, microbes and temporal outline from immunosuppressive therapy in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis with native renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015 Apr;30(Suppl 1):i171–81. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tieder JS, Hall M, Auger KA, Hain PD, Jerardi KE, Myers AL, et al. Accuracy of administrative billing codes to detect urinary tract infection hospitalizations. Pediatrics. 2011 Aug;128(2):323–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roumie CL, Mitchel E, Gideon PS, Varas-Lorenzo C, Castellsague J, Griffin MR. Validation of ICD-9 codes with a high positive predictive value for incident strokes resulting in hospitalization using Medicaid health data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008 Jan;17(1):20–6. doi: 10.1002/pds.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John Michet C, 3rd, Crowson CS, Achenbach SJ, Matteson EL. The Detection of Rheumatic Disease through Hospital Diagnoses with Examples of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Giant Cell Arteritis: What Are We Missing? J Rheumatol. 2015 Nov;42(11):2071–4. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.