Abstract

Background

Using American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and Systemic Lupus (SLE) International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria for SLE classification as gold standards, we determined sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) of having SLE denoted as the primary cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States Renal Data Systems (USRDS).

Methods

ESRD patients were identified by ICD9 codes in electronic medical records of one large tertiary care center, Montefiore hospital, from 2006 to 2012. Clinical data were extracted and reviewed to establish SLE diagnosis. Data were linked by social security number, name, and date of birth to USRDS where primary causes of ESRD was ascertained.

Results

Of 7396 ESRD patients at Montefiore, 97 met ACR/SLICC SLE criteria, and 86 had SLE by record only. Among the 97 SLE patients, the attributed causes of ESRD in the USRDS were as follows: 77 SLE, and 12 with other causes (unspecified glomerulonephritis, hypertension, scleroderma), and 8 missing. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV for SLE in USRDS were 79%, 99.9%, 93%, and 99.7%, respectively. Of the 60 patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis, 44 (73%) had SLE as primary ESRD cause in USRDS. Attribution of the primary ESRD causes among SLE patients with ACR/SLICC criteria differed by race, ethnicity, and transplant status.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of SLE as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS has good sensitivity, and excellent specificity, PPV and NPV. Nationwide access to medical records and biopsy reports may significantly improve sensitivity of SLE diagnosis.

Introduction

It is estimated that 10–30% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) within 10 years, even with aggressive therapies (1, 2). Mortality among SLE ESRD patients is 4-fold higher than among SLE patients with lupus nephritis alone (3). In addition, mortality in SLE ESRD is twice as high as mortality in non-SLE ESRD, even though SLE patients are significantly younger when they develop ESRD (4, 5). Improving outcomes in SLE ESRD is a critical step to decreasing ESRD-related morbidity and mortality for SLE patients.

There are multiple challenges to the study of SLE ESRD, however, including relatively small numbers of SLE ESRD cases, lack of consistent follow-up with healthcare providers, and difficulty capturing outcomes over time. Some of these challenges may be addressed by using data from the United States Renal Data Systems (USRDS) registry, an NIH-funded national data registry that was created for outcomes research for patients with chronic ESRD. The over 11,000 prevalent SLE cases reported as of 2011 (2013 USRDS Annual report), include diverse populations, comprehensive demographic and laboratory Medicare claims, and mortality data (6). The majority of the studies related to epidemiology and outcomes in SLE ESRD in the US have been conducted using the USRDS data (reviewed in 7, 8). Nephrologists are required to submit the Centers for Medicare services (CMS) Medical Evidence Report (F2728 form) for each new patient, identifying the primary cause of ESRD, and providing baseline demographic and laboratory data at the time of ESRD onset. One of the potential limitations of the USRDS is that the identification of patients with SLE as the cause of their ESRD is based on the diagnosis by the treating nephrologist listed on the F2728 form. The accuracy of this diagnosis compared to the established SLE criteria has not been established.

Using American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria for SLE classification as gold standards, we determined sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of SLE as the primary cause of ESRD in a subset of the USRDS patients followed at a large tertiary care center. In addition, SLE patients who had SLE listed as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS were compared with SLE patients who had non-SLE listed as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS to elucidate potential systematic biases.

Methods

To establish the accuracy of the SLE diagnosis in USRDS, we identified ESRD patients within the Montefiore electronic record system (EMR). Montefiore is a community-based urban tertiary care center that provides primary and specialty care to over 2 million people in the Bronx, New York. ESRD at Montefiore was defined as either inpatient or outpatient visits between 2006 and 2012, with at least one ICD9 code for: chronic kidney disease stage V (585.5); ESRD (585.6); complications of kidney transplant (996.81); kidney transplant status (V42); encounter for dialysis (V56); or admit for renal dialysis (V56.0). Data were linked by social security number, name, and date of birth to the USRDS data from the same time period. Primary causes of renal failure from the USRDS were ascertained. Records of patients who had SLE listed as the primary ESRD cause in the USRDS, or at least one billing ICD9 code for SLE or related conditions (710.*) within the hospital electronic medical record system, were reviewed by one board-certified rheumatologist (AB) for the ACR and SLICC criteria for classification of SLE(9–11), to ascertain possible ESRD causes in these patients, and to document the presence of renal biopsies consistent with lupus nephritis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Data were obtained from the USRDS through a data use agreement in compliance with USRDS reporting policies.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) for SLE as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDs were computed with ACR and/or SLICC criteria as the gold standard. In a sensitivity analysis, ESRD patients were considered to have SLE-related ESRD if they had documentation of SLE in the medical record (not strictly meeting ACR or SLICC criteria), similar to the validation criteria used to validate SLE in the Georgia Lupus Registry cohort (12). Patients who had insufficient information in their charts to be classified as SLE versus non-SLE were excluded from the calculations. Patients with missing diagnoses in the USRDS were counted as non-SLE in the primary analyses, similar to the study by Layton, et al. (13). In the additional analyses, the sensitivity of the SLE diagnosis in the USRDS using ACR/SLICC as the gold standard was recalculated excluding patients with missing primary causes of ESRD in the USRDS.

To explore potential biases related to SLE attribution in the USRDS, SLE patients with established ACR/SLICC criteria were divided into SLE patients who had SLE listed as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS, and SLE patients who had non-SLE causes listed as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS. These two groups were compared using Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests (for continuous variables) and Pearson’s Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests (for categorical variables). Race was recorded in the USRDS based on the data collected in the 2728 Medical Evidence form, and analyzed as White and Black (only one patient has race listed as “other”). Ethnicity was recorded as Hispanic/non-Hispanic. Other variables from the USRDS that were used for comparisons included age at the ESRD onset, sex, the number of patients who started hemodialysis as the initial renal replacement modality, and the number of patients who received at least one renal transplant. Statistical analysis was performed using the STATA 12.0 software package (StataCorp, College Station, Tx). In accordance with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services release of data requirements, cells with fewer than 10 patients per cell were suppressed in the tables.

Results

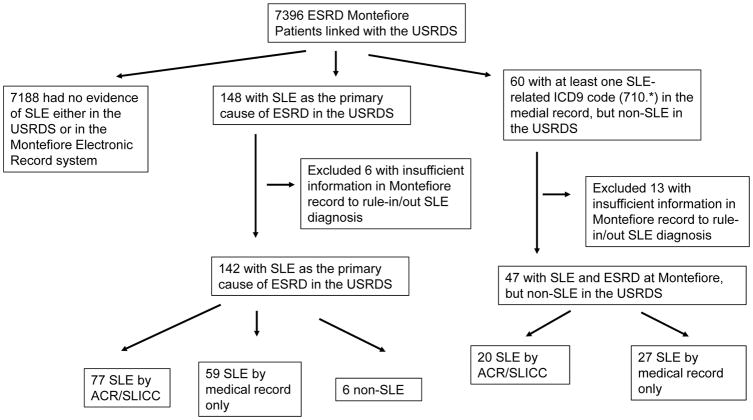

We identified 7396 ESRD patients at Montefiore seen between 2006 and 2012 that were linked to the USRDS. Of them, 7188 had no evidence of SLE either in the USRDS or in the Montefiore electronic record system, and were defined as non-SLE (Figure 1). There were 148 (2%) patients with SLE listed as the primary ESRD cause in the USRDS. Sixty patients had at least one SLE-related (710.*) diagnosis in the Montefiore electronic medical record, but had non-SLE causes of ESRD listed in the USRDS.

Figure 1.

Validation of SLE diagnosis in the USRDS inclusion/exclusion flow chart

Of the 148 patients with SLE listed as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS, 6 had insufficient information in the medical records at Montefiore to either confirm or rule-out the diagnosis of SLE or to determine the etiology of ESRD, and were excluded from the study sample. Of the 142 remaining patients, 77 (54%) had confirmed SLE by ACR and/or SLICC criteria (ACR/SLICC) after review of the medical records, and 59 had documentation of SLE in their medical records, but insufficient information to establish ACR/SLICC criteria. Six (4%) did not have SLE and had following diagnoses: mixed-connective tissue disease, positive anti-nuclear antibody without SLE, and membranous glomerulonephritis on renal biopsy with negative immunofluorescence. Of the 60 patients with at least one ICD9 code for SLE-related conditions, 13 did not have sufficient information in the records to either confirm or rule-out the diagnosis of SLE or to determine the etiology of ESRD, and were excluded from the study sample. Of the remaining 47 patients, 20 met ACR/SLICC criteria for SLE based on medical record, 27 had SLE documented in their medical records but did not have sufficient information to establish ACR or SLICC criteria. Therefore, the final study sample included 7377 patients; 19 (6 with SLE listed as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS and 13 identified as SLE in EMR by ICD 9 code) were excluded from all calculations as they had insufficient information to confirm or rule-out the diagnosis of SLE.

Of the 97 patients with SLE by ACR/SLICC criteria, the attributed causes of ESRD in the USRDS were distributed as follows: 77 SLE, 8 missing, and 12 with other causes (scleroderma, hypertension, unspecified glomerulonephritis). Among the additional 27 Montefiore patients who had SLE according to their medical records, but non-SLE primary causes of ESRD in the USRDS, the attribution of ESRD was as follows: 5 missing, 22 with other causes, including hypertension, diabetes, unspecified glomerulonephritis, amyloidosis, sickle cell disease and acute interstitial nephritis.

Calculations of sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV are shown in Table 1: with the established ACR/SLICC criteria as the gold standard, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV in USRDS were 79%, 99.9%, 93%, and 99.7%, respectively. The sensitivity decreased slightly, but the specificity, PPV and NPV did not change significantly in our sensitivity analysis including all patients with SLE according to Montefiore medical records: 74%, 99.9%, 96%, 99.4%, respectively. The sensitivity of SLE as the primary cause of ESRD according to ACR/SLICC criteria increased from 79% to 87% when 8 SLE patients with ACR/SLICC who had missing causes of ESRD in the USRDS were excluded from the calculations. We also recalculated the sensitivity after including 6 patients who had SLE listed as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS, but were excluded from the main analyses because of insufficient information to establish the diagnosis of SLE or to determine the etiology of ESRD. Assuming these patients had SLE increased the sensitivity to 81%.

Table 1.

Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of SLE as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS

| 1a. SLE diagnosis validation using the American College of Rheumatology/SLE Collaborating Clinics Criteria for SLE Classification (ACR/SLICC) from medical record review at Montefiore Medical Center as the gold standard | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montefiore Medical record review for SLE by ACR/SLICC | |||||

| USRDS Primary Cause of ESRD | SLE+ | SLE− | Total | ||

| SLE+ | 77 | 6 | 83 | PPV 93% | |

| SLE− | 20 | 7188 | 7207 | NPV 99.7% | |

| Total | 97 | 7194 | 7291 | ||

| Sensitivity 79% | Specificity 99.9% | ||||

| 1 b. SLE diagnosis validation using documentation of SLE on medical record review at Montefiore Medical Center as the gold standard | |||||

| Montefiore Medical record review for SLE by documentation of SLE | |||||

| USRDS Primary Cause of ESRD | SLE+ | SLE− | Total | ||

| SLE+ | 136 | 6 | 142 | PPV 96% | |

| SLE− | 47 | 7188 | 7235 | NPV 99.4% | |

| Total | 183 | 7194 | 7377 | ||

| Sensitivity 74% | Specificity 99.9% | ||||

SLE patients with confirmed ACR/SLICC criteria classified as SLE in the USRDS were more likely to be non-black, Hispanic, and had a higher proportion of patients who received a kidney transplant (Table 2). No significant differences were found with respect to age, sex, hemodialysis as the initial modality, or year of ESRD onset.

Table 2.

Comparisons of SLE patients with established ACR/SLICC criteria who had SLE vs. non-SLE primary causes of ESRD in the USRDS at the Montefiore Medical Center*

| ACR/SLICC+ SLE classified as SLE in the USRDS N=77 |

ACR/SLICC+ SLE classified as non-SLE in the USRDS N=20 |

p value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age at ESRD onset, mean (SD), years | 37 (13) | 45 (16) | 0.11 |

|

| |||

| Sex, n(%) men | 10 (13) | - | 0.30 |

|

| |||

| Black race, n(%) | 41 (54) | 15 (79) | 0.048 |

|

| |||

| Hispanic ethnicity, n(%) | 44 (58) | - | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Hemodialysis as the initial renal replacement modality | 68 (88) | 20 (100) | 0.11 |

|

| |||

| Transplant recipients, n (%) | 40 (52) | - | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Year of ESRD recorded | |||

| <2004 | 24 (31) | - | |

| 2004–2009 | 40 (52) | - | |

| >2009 | 13 (17) | - | 0.11 |

In accordance with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services release of data requirements, cells with fewer than 10 patients per cell were suppressed

p-value for Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables, and Pearson’s Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables

Among 60 patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis, 16 (27%) had non-SLE listed as the primary ESRD cause in the USRDS: 7 missing the primary ESRD cause in the USRDS, and 9 “other”, including scleroderma, hypertension, and other glomerulonephritis. All patients with hypertension as the primary ESRD cause had documented hypertension highlighting the clinical challenges of determining whether ESRD in SLE patients is the direct result of lupus nephritis, even in patients with biopsy proven renal involvement. Most patients with “glomerulonephritis” listed as the primary ESRD cause in the USRDS had documented biopsies consistent with lupus nephritis.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the diagnosis of SLE as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS has good sensitivity (79%), and excellent specificity (99.9%), PPV (93%) and NPV (97%). These findings are robust whether we employed ACR/SLICC criteria for SLE classification or medical record documentation of SLE. These findings are of high importance as they support the validity of multiple past and future studies of SLE ESRD using USRDS data.

The sensitivity was higher when ACR/SLICC criteria were used as the gold standard, and when patients with missing primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS were excluded from the calculations. The sensitivity of SLE as the primary cause of ESRD in USRDS can be further improved by making biopsy results and medical records from different institutions readily available to providers at the time of completion of the CMS Medical Evidence Report for each new ESRD patient. The sensitivity can also be improved by excluding patients with the missing causes of ESRD in the USRDS from future studies of SLE in the USRDS.

The specificity is extremely high: 99.9% of SLE ESRD cases at Montefiore were correctly classified in USRDS. Similarly the NPV of 99% indicates that virtually all true negatives (those without SLE) were correctly classified as other causes of ESRD.

To our knowledge, only two past studies have examined the accuracy of the SLE diagnosis code of primary ESRD cause in the USRDS and from slightly different vantage points. Layton et al. studied the validity of the 2001 USRDS primary cause of renal failure codes compared to renal biopsy findings in a subset of USRDS patients who had stored biopsy information in the Glomerular Diseases Collaborative Network. In that study, there were 30 patients who had a biopsy consistent with lupus nephritis. Of them, only 8 (27%) had a diagnosis of SLE listed on the CMS Medical Evidence Report. Since that study was conducted, the Medical Evidence form has been simplified and modified to improve accuracy, and electronic medical records have been widely implemented in the U.S. In the current study, the number of those missing primary cause of renal failure among SLE patients has decreased substantially, and only 8% of patients with SLE confirmed by ACR/SLICC criteria had missing primary diagnoses in the USRDS. Although the frequency of missing diagnoses was reduced significantly, 30% of patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis still had non-SLE diagnoses listed as the primary cause of ESRD in the USRDS. In the current study, the gold standard for SLE validation was the ACR or SLICC criteria, not biopsy report.

A recent study from the Georgia Lupus Registry cohort by Plantinga et al reported a sensitivity for SLE of 79% (14). In that study, the attribution of cause of ESRD in USRDS was studied among 251 SLE patients who developed ESRD and thus they were only able to establish the sensitivity of SLE in USRDS. That study defined SLE either by ACR/SLICC criteria or by the medical record. Although both their study and ours have reported a sensitivity 79%, we have shown that the sensitivity is higher when ACR/SLICC criteria are used as the gold standard. In contrast to the study by Plantinga et al. we examined the medical records of all patients with ESRD --with and without SLE--from a single tertiary care center, enabling us to also establish the specificity, PPV, and NPV of the USRDS coding.

There are several potential limitations to the current study, including a single center design and a relatively large proportion of patients with insufficient information to establish ACR/SLICC criteria. However, the findings did not change significantly in the sensitivity analyses suggesting robustness of our findings. In addition, the sensitivity of the SLE diagnosis in the USRDS determined in our study was very similar to the sensitivity of the SLE diagnosis derived from the data from the Georgia Lupus Registry. Therefore, the external validity and generalizability of our findings are good.

One of the major strengths of our study is that we have used ACR/SLICC criteria to validate the diagnosis of SLE in the USRDS. Although renal biopsy is the gold standard to diagnose lupus nephritis, renal biopsy reports were not available for all subjects. ACR/SLICC criteria for classifications are routinely used to define SLE patients in research (15). Our findings were similar looking at various subsets of patients and using different diagnostic criteria.

Using ACR/SLICC criteria as the gold standard, we validated the diagnosis of SLE in the USRDS and showed that the SLE diagnosis is highly accurate in the USRDS. Given the wealth of data in the USRDS, using USRDS is an efficient, cost-effective, and statistically powerful approach for conducting epidemiologic studies in SLE ESRD.

Significance and Innovation.

The accuracy of the SLE diagnosis in the USRDS, using ACR/SLICC criteria as the gold standard, has not been previously established. Therefore, we validated the diagnosis of SLE in the USRDS.

SLE as the primary cause of end-stage renal disease in the USRDS has good sensitivity (79%), and excellent specificity (99.9%), positive predictive value (93%), and negative predictive value (99.7%).

Nationwide access to medical records and biopsy reports may significantly improve sensitivity of SLE diagnosis.

These findings are of high importance as they support the validity of multiple past and future studies of SLE ESRD using USRDS data.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funding for this project was provded by the Rheumatology Research Foundation Career Development Bridge Funding Award: K Bridge. Dr. Costenbader is supported by NIH K24 AR 066109 and R01 AR057327.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Contributor Information

Anna Broder, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York.

Wenzhu B. Mowrey, Division of Biostatistics, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY.

Peter Izmirly, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Karen H. Costenbader, Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy, Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Hanly JG, O’Keeffe AG, Su L, Urowitz MB, Romero-Diaz J, Gordon C, et al. The frequency and outcome of lupus nephritis: results from an international inception cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55(2):252–62. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costenbader KH, Desai A, Alarcon GS, Hiraki LT, Shaykevich T, Brookhart MA, et al. Trends in the incidence, demographics, and outcomes of end-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis in the US from 1995 to 2006. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(6):1681–8. doi: 10.1002/art.30293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yap DY, Tang CS, Ma MK, Lam MF, Chan TM. Survival analysis and causes of mortality in patients with lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(8):3248–54. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sule S, Fivush B, Neu A, Furth S. Increased hospitalizations and death in patients with ESRD secondary to lupus. Lupus. 2012;21(11):1208–13. doi: 10.1177/0961203312451506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sule S, Rosen A, Petri M, Akhter E, Andrade F. Abnormal production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by lupus monocytes in response to apoptotic cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foley RN, Collins AJ. The USRDS: what you need to know about what it can and can’t tell us about ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(5):845–51. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06840712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inda-Filho A, Neugarten J, Putterman C, Broder A. Improving outcomes in patients with lupus and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2013;26(5):590–6. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabucedo AJ, Contreras G. ESKD, Transplantation, and Dialysis in Lupus Nephritis. Semin Nephrol. 2015;35(5):500–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25(11):1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8):2677–86. doi: 10.1002/art.34473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim SS, Bayakly AR, Helmick CG, Gordon C, Easley KA, Drenkard C. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus, 2002–2004: The Georgia Lupus Registry. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):357–68. doi: 10.1002/art.38239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Layton JB, Hogan SL, Jennette CE, Kenderes B, Krisher J, Jennette JC, et al. Discrepancy between Medical Evidence Form 2728 and renal biopsy for glomerular diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(11):2046–52. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03550410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plantinga LC, Drenkard C, Pastan SO, Lim SS. Attribution of cause of end-stage renal disease among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: the Georgia Lupus Registry. Lupus Sci Med. 2016;3(1):e000132. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2015-000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ines L, Silva C, Galindo M, Lopez-Longo FJ, Terroso G, Romao VC, et al. Classification of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Versus American College of Rheumatology Criteria. A Comparative Study of 2,055 Patients From a Real-Life, International Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67(8):1180–5. doi: 10.1002/acr.22539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]