Abstract

Disruption of normal circadian rhythms and sleep cycles are consequences of aging and can profoundly impact health. Accumulating evidence indicates that circadian and sleep disturbances, which have long been considered symptoms of many neurodegenerative conditions, may actually drive pathogenesis early in the course of these diseases. In this review we explore potential cellular and molecular mechanisms linking circadian dysfunction and sleep loss to neurodegenerative diseases, with a focus on Alzheimer’s Disease. We examine the interplay between central and peripheral circadian rhythms, circadian clock gene function, and sleep in maintaining brain homeostasis, and discuss therapeutic implications. The circadian clock and sleep can influence a number of key processes involved in neurodegeneration, suggesting that these systems might be manipulated to promote healthy brain aging.

Introduction

Although Ben Franklin’s aphorism “early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise” may not be universally true, he implies that less reliable bedtime hours will earn us poor health, financial poverty, and cognitive impairment. This old adage is particularly relevant today as it pertains to the relationship between circadian rhythms, sleep, and neurodegenerative diseases. Circadian and sleep dysfunction have long been symptomatic hallmarks of a various devastating neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer Disease (AD), Parkinson Disease (PD), and Huntington Disease (HD) (1, 2). Accumulating evidence indicates that disorders of sleep and of circadian rhythms may occur very early in course of several neurodegenerative diseases and serve not only as manifestations of disease but may potentially contribute directly to pathogenesis(3–5). Herein, we discuss the existing data linking circadian and sleep disruption to neurodegeneration, explore several potential molecular mechanisms linking the circadian clock to neurodegeneration, and address potential therapeutic implications.

The circadian clock in the brain

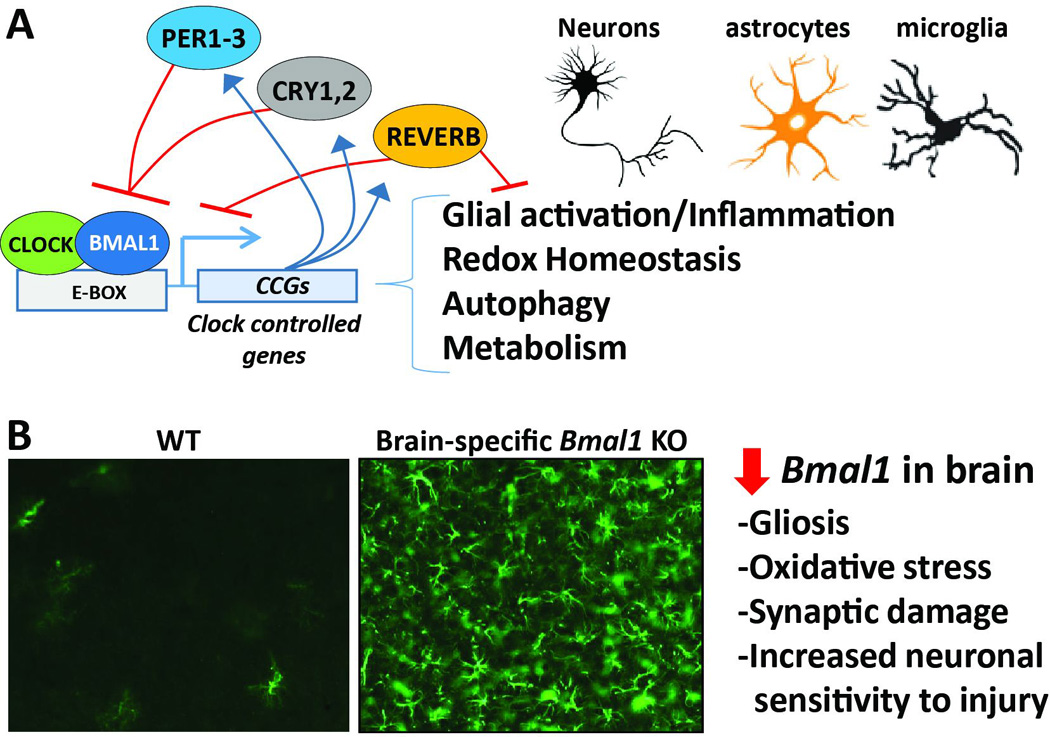

The circadian system in humans and mice is hierarchical, existing at both the molecular and circuit-based levels (Fig. 1). At the cellular level, the core circadian clock consists of a set of conserved clock proteins which form a transcriptional-translational feedback loop that mediates daily oscillations in gene expression. In humans and mice, the positive transcriptional limb of the circadian clock consists of the basic helix-loop-helis PER-ARNT Sim transcriptional factor BMAL1 (aka ARNTL), which heterodimerizes with CLOCK (or NPAS2), binds to Ebox motifs throughout the genome, and drives transcription of a host of genes (6, 7) (Fig. 3A). Among the transcriptional targets of BMAL1-CLOCK complexes are several negative feedback regulators, including the PERIOD (PER1-3), CRYPTOCHROME (CRY1,2), and REVERB (NR1D1 and NR1D2) genes, which then suppress the positive limb. The core circadian clock oscillates in a cell-autonomous manner and is tuned to a 24-hour period by multiple layers of posttranslational regulation. The positive limb of the clock regulates transcription of hundreds or thousands of transcripts in a tissue-and cell-type specific manner (8). In mice and humans, cellular oscillators are synchronized across organs by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. The SCN receives light:dark input from the retina, synchronizing core clock oscillations in neurons which are then translated into oscillatory synaptic output to multiple nuclei in the hypothalamus and elsewhere. Ablation of the SCN leads to a loss of these patterns in neuronal activity, as well as a loss of coherent circadian rhythms in clock gene oscillations in most tissues, and ultimately behavioral and physiological arrhythmicity. The SCN clock is also entrained by changes in the light:dark cycle and mediates shifts in peripheral circadian rhythms in this setting.

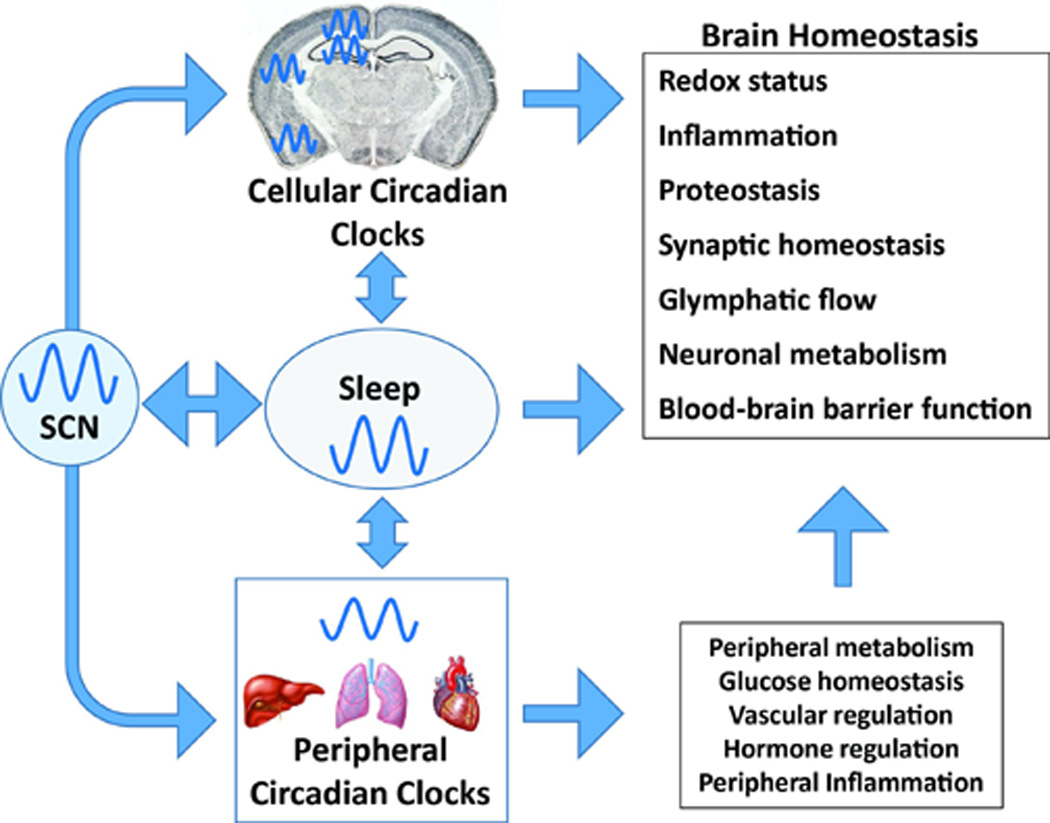

Figure 1. Impact of sleep, central, and peripheral circadian rhythms on brain homeostasis.

The SCN synchronizes circadian rhythms in the cellular clocks of cells in the brain, the sleep wake cycle, and peripheral organs. Cellular clocks within neurons and glia in turn regulate transcription of genes involved in critical processes such as redox homeostasis, inflammation, proteostasis, and metabolism. Sleep influences many of the same pathways, perhaps in some cases through interaction with the clock. Circadian regulation of peripheral metabolism, inflammation, and hormone secretion also impacts the brain.

Figure 3. Core clock genes in the brain regulate neurodegeneration.

A. Schematic depicting the core circadian clock. Bmal1 drives transcription of a wide array of clock-controlled genes, which regulate key processes involved in neurodegeneration. The circadian transcriptome could vary between neurons, astrocytes, and microglia. B. Disruption of the cellular clock in the brain with sparing of SCN function, achieved in Nestin-Cre;Bmal1flox/flox mice, causes severe reactive astrogliosis in cerebral cortex (as assessed by GFAP staining), and promotes oxidative stress and neuronal injury.

Dissection of the circadian system can be complicated. Ablation of the SCN abrogates circadian rhythms in nearly all outputs, including sleep (9). However, rodents without a functioning SCN still have intact peripheral clock gene expression, though the levels may not oscillate (10) . Arrhythmic mice also still sleep, just with no day-night predilection. Mice can also be rendered arrhythmic through deletion of specific circadian clock genes, in particular Bmal1 (11). Global Bmal1 deletion not only renders the SCN arrhythmic, but also disrupts cellular clock function. Local, tissue-specific deletion of key clock genes, such as Bmal1, in non-SCN regions of the brain can also render that tissue transcriptionally arrhythmic without altering the animal’s sleep-wake cycle or behavioral rhythms (12). One caveat is that Bmal1 can exert developmental effects, and regulates many genes that are non-rhythmic, suggesting that some effects of Bmal1 deletion may be non-circadian(13).

More complexity comes when considering the interplay between the circadian clock and sleep. Mutations in circadian clock genes, both in mice and in humans, manifest behaviorally as sleep disturbances (14, 15). Conversely, sleep deprivation can alter the expression (16, 17), and DNA binding activity of core clock genes(18), demonstrating a bi-directional relationship between sleep and the circadian clock.

Sleep and Neurodegeneration

A wide variety of alterations in sleep have been described in human neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, PD, and HD, and are reviewed elsewhere(19, 20). In each of these diseases, sleep disturbances may precede the onset of more typical symptoms, in some cases by decades (3–5). The most striking example is REM behavior disorder (RBD), a condition in which normal muscle paralysis is lost during REM sleep. Over 80% of all RBD patients will eventually develop PD or another synucleinopathy, often decades later (5). Mouse models of AD, PD, and HD pathology also exhibit sleep abnormalities (21–24). Sleep deprivation increases cerebrospinal fluid markers of neuronal injury and alters plasma markers of inflammation in humans (25, 26), and induces the unfolded protein response in the brain of mice, indicating endoplasmic reticulum stress and potential neuronal injury (27). Thus, inadequate sleep could prime the brain for neurodegeneration by promoting processes such as inflammation and synaptic damage which exert pathogenic effects across diseases.

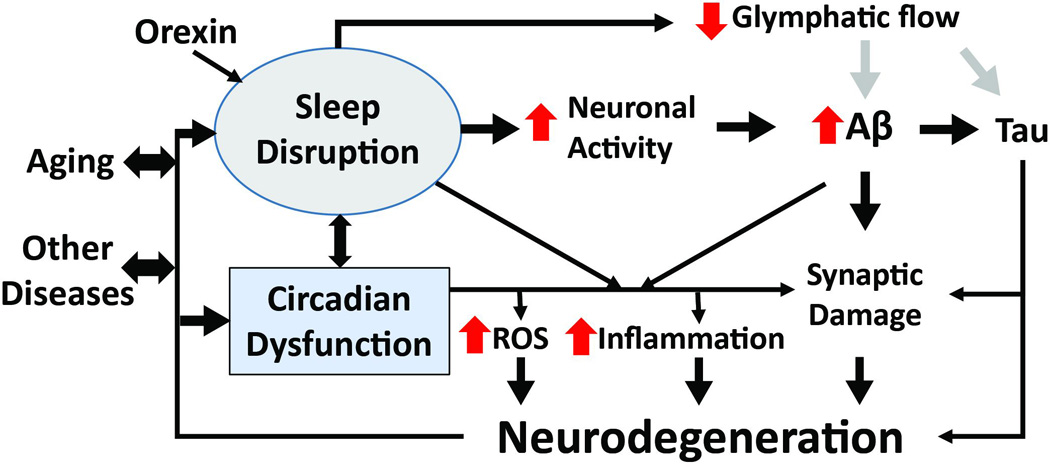

The relationships between sleep and disease-specific pathways have most clearly been demonstrated in the case of amyloid-beta (Aβ), a pathogenic protein instrumental in AD (Fig. 2). Amyloid plaques, which form as a result of aggregation of Aβ species, accumulate in the brains of AD patients years before the onset of cognitive impairment and serve as an early biomarker of AD(28). Neurons release Aβ in an activity-dependent manner, and Aβ concentrations in the extracellular space in the brain exhibit clear circadian oscillations, rising during the active period and falling during rest(29). These diurnal fluctuations in Aβ persist in constant darkness, and are closely correlated to changes in neuronal metabolic activity tied to sleep and wake. Similar Aβ oscillations can be observed in the cerebrospinal fluid of humans (30). In transgenic mouse models of Aβ deposition like that seen in AD, sleep deprivation greatly accelerates amyloid plaque deposition, whereas promoting sleep with orexin antagonist drugs significantly inhibits plaque formation (29). Genetic deletion of orexin, a peptide expressed in the lateral hypothalamus that promotes wakefulness and regulates feeding and metabolism, modestly increases sleep time but strongly suppresses the formation of amyloid plaques in AD model mice (31). These basic and translational studies are concordant with epidemiological studies showing that deficient or fragmented sleep in cognitively-normal individuals is a risk factor for the future development of symptomatic AD (3, 4, 32), and that people with amyloid plaque pathology develop detectable declines in sleep efficiency prior to the onset of cognitive symptoms (33). Human studies have also shown a correlation between concentrations of orexin in the cerebrospinal fluid and that of tau protein, another pathologic hallmark of AD and the primary constituent of neurofibrillary tangles. High concentrations of CSF orexin-A, which promote increased wakefulness, were associated with increased amounts of phophorylated tau, a well-described biomarker of neurodegeneration in AD (34), though not with CSF Aβ concentration (35). Sleep deprivation also exacerbated tau pathology and synapse loss in a mouse model of AD which develops both Aβ and tau pathology (36, 37), though the effects of sleep on tau are not yet fully understood.

Figure 2. Proposed mechanisms linking sleep loss, Aβ, and neurodegeneration in AD.

Sleep deprivation or fragmentation can result from aging, other diseases, environmental influences, circadian clock (SCN) dysfunction, or neurodegeneration. Increased wakefulness, which is promoted by orexin, causes increased neuronal activity, leading to elevated Aβ production and aggregation. Wakefulness also increases sympathetic output, suppressing glymphatic system function. This could result in decreased clearance of pathogenic proteins (such as Aβ, tau, or synuclein). Sleep loss and clock disruption also promotes oxidative stress, inflammation and a loss of synaptic homeostasis. These insults combine to promote neurodegeneration, which in turn causes more circadian and sleep dysfunction.

A rich literature has demonstrated the critical tie between sleep, synaptic function, and cognition, which is reviewed elsewhere (38). Sleep disturbances in aging and neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, can directly influence synaptic homeostasis and cognitive function. As an example, Aβ plaque pathology in the medial prefrontal cortex in humans is associated with disrupted non-REM sleep which appears to cause impaired learning and memory (39).

Sleep also appears to regulate the bulk removal of proteins and other molecules from the brain through regulation of “glymphatic” flow, a recently-described phenomenon whereby astrocytes facilitate extracellular fluid transit though the brain (40). In mice, slow-wave sleep was associated with increased glymphatic flow, causing a ~60% increase in brain interstitial fluid volume and facilitating accelerated clearance of exogenously-added Aβ from the brain (41). Blockade of noradrenergic receptors increased glymphatic flow, suggesting that increased noradrenergic output from the autonomic nervous system, as is seen during waking, suppresses glymphatic clearance. As sleep deprivation in mice can cause degeneration of neurons in the locus coeruleus, the primary noradrenergic nucleus in the brainstem (42), the effect of chronic sleep disturbances on glymphatic function remains uncertain.

In HD, sleep fragmentation is detectable in carriers of the pathogenic CAG- expanded huntingtin gene before the onset of cognitive symptoms (43). Mouse models of HD exhibit severe degeneration of sleep rhythms (23, 44), and pharmacologic restoration of sleep by treatment of mice with the sedative clonazepam at the onset of the light phase normalizes clock gene oscillation in these mice and significantly improves cognitive performance (45). In this case, the primary dysfunction appears to be in the circadian system, though normalizing the sleep pattern also corrects the circadian deficit, emphasizing the complex interaction between sleep and circadian clocks.

Circadian function and neurodegeneration

Aging is a primary risk factor for many neurodegenerative conditions, and circadian function clearly wanes with age at the level of the SCN output and brain clock gene expression(46, 47). Alterations in behavioral circadian rhythms are evident in patients with several neurodegenerative conditions and in mouse models of these diseases, and are reviewed in detail elsewhere(1). AD patients have loss of critical neurons in the SCN, a finding which correlates with impaired behavioral circadian function (48, 49). One post-mortem study demonstrated asynchronous clock gene expression between different brain regions in AD patients (50). Aβ can facilitate BMAL1 degradation in neuronal cells (51), suggesting that AD-related processes could directly influence cellular clock function. PD patients have blunted rhythms of clock gene expression in peripheral blood cells (52, 53), and transgenic mice overexpressing human alpha-synuclein, a neurodegenerative protein implicated in PD, develop behavioral and transcriptional circadian deficits (22). Mouse models of HD also exhibit severely disrupted SCN output and loss of peripheral clock gene oscillation early in the disease course (44, 54). Interestingly, in aged mice, as well as some HD and PD models, there is intact clock gene oscillation in the SCN but disrupted electrical output, suggesting neuronal network dysfunction in the SCN as the primary lesion (22, 44, 46). Thus, circadian dysfunction can result from lesions at multiple levels of the circadian system.

Although it is well established that neurodegeneration impacts the circadian clock, few studies have addressed the causality of this dysfunction in neurodegeneration. In humans, less robust circadian rhythms or more fragmented activity patterns appear to be risk factors for future dementia, suggesting a possible causative influence of circadian dysfunction on the neurodegenerative process (55). Several small studies have associated single nucleotide polymorphisms in Clock and Bmal1 with increased risk of AD or PD (56–58). To address this question, we have examined the evidence linking SCN disruption and whole-organism rhythms separately from studies examining clock gene deletion.

Disrupted SCN-mediated circadian rhythms and neurodegeneration

Alterations in coordinated whole-organism circadian function caused by SCN disruption or altered light:dark cycles could have profound impact on the brain, either by disrupting normal oscillation of cellular clocks in various brain regions, or by disrupting other rhythms, such as the sleep-wake cycle, or rhythms in peripheral organs (Fig. 1). Notably, the circadian clock regulates hippocampal-dependent learning and has potent effects on cognition in the absence of neurodegeneration (59–61). As an example, simply misaligning the sleep and feeding rhythms in mice causes desynchrony of clock gene oscillation between the SCN and hippocampus, resulting in significant impairments in learning and memory (62). Loss of rhythms in melatonin, a hormone involved in circadian timing, has been observed in several neurodegenerative diseases (63, 64), and melatonin supplementation has been explored as a therapeutic for AD, with modest effect(65). Loss of circadian regulation of peripheral processes such as glucose and lipid metabolism (7), immune system function (66–68), hormone secretion, or even gut microbiome oscillations (69) could potentially indirectly predispose the brain to degeneration. Many non-genetic models of circadian disruption, such as “jetlag” phase advance protocols, which simulate eastward travel by shifting the time of “lights on” to an earlier time by several hours every few days, induce effects on both the periphery and the brain. Mice exposed to “jetlag”, which induces circadian desynchrony, exhibit increased amounts of inflammatory markers in the blood (70), diminished hippocampal neurogenesis, and impaired learning and memory (71). Altered light:dark schedules, such as a 10hr:10hr light:dark paradigm, can also disrupt SCN-mediated rhythms and cause peripheral metabolic alterations, leading to decreased dendritic arborization of cortical neurons and behavioral impairments (72). As a human corollary, intercontinental flight attendants subjected to frequent jetlag exhibited hippocampal atrophy, a common feature of AD, when compared to non-jetlagged colleagues (73). Thus, the mechanisms linking SCN-mediated circadian rhythms to neurodegeneration are likely multiple and interrelated, and require more detailed analysis in mouse disease models and in humans.

Disrupted cellular clocks and neurodegeneration

Circadian clock genes are universally expressed in most cells of the brain, including neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, each of which exhibit circadian clock gene oscillations in culture (74, 75). Transcriptomic studies of cerebellar and brain stem samples from mice demonstrate that several hundred genes exhibit circadian oscillations (8). But what do these brain clocks do? And are they important to brain health?

Some insight into these questions can be derived from recent studies of mice harboring deletion of Bmal1, which lack detectable circadian rhythms in behavior, sleep-wake cycle, and gene transcription (11). Bmal1 deficient mice develop striking neurological phenotypes, including profound spontaneous astrogliosis, increased oxidative damage, synaptic degeneration, impaired brain functional connectivity (12), impaired learning and memory (60), altered hippocampal neurogenesis (76–78), and lowered seizure threshold (79). In some of these cases, it remains unclear if the phenotype is due to loss of Bmal1 in the cells of the brain itself, or secondary to whole-animal changes in metabolism. However, mice with brain-specific Bmal1 deletion which spares the SCN (leaving sleep and peripheral rhythms intact) still develop severe astrogliosis and neuronal loss (12)(Fig. 3B). Thus, the positive limb of the circadian clock in the brain appears to be critical for maintaining normal brain function and health independent of sleep or peripheral rhythms. While the mechanisms linking the cellular circadian clock to neurodegeneration are not fully known, we propose below several candidate molecular processes which exhibit regulation by the clock that are likely contributors to neurodegeneration across diseases (Fig. 3).

Oxidative stress

Neurons are highly sensitive to free radical-mediated injury, and oxidative stress is a conserved pathogenic mechanism in nearly every neurodegenerative condition. Redox homeostasis has been closely linked to the circadian clock across multiple cell and tissue types, and across organisms. Circadian oscillations in peroxiredoxin 6 oxidation occur in organisms ranging from fungi to fruit flies to mice(80). Cellular concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and of the intracellular antioxidant glutathione, exhibit circadian oscillations in drosophila brain(81) and in cultured fibroblasts(82). Redox oscillations are detectable in the SCN, and alteration of SCN redox state influences neuronal activity and circadian output(83). Oxidative stress in flies causes circadian disruption and sleep fragmentation like that seen in aging(84). Conversely, disruption of the circadian system by deletion of Bmal1 causes increased oxidative stress in multiple organs in mice(85), including the brain(12). Bmal1 drives transcription of redox-related genes in the brain, including Nqo1 and Aldh212). As ROS are produced as byproducts of increased neuronal activity in the brain, the circadian clock may serve to temporally coordinate the expression of redox defense genes with diurnal variations in brain metabolic activity. Thus, disruption of normal circadian function in the setting of neurologic disease might render the brain more vulnerable to oxidative injury and thereby promote neurodegeneration. Accordingly, diminished Bmal1 expression exacerbates neuronal death caused by oxidative stress both in vitro and in vivo(12).

Inflammation

Neuroinflammation, often propagated by activation of astrocytes and microglia, is a major contributor to neurodegeneration. Astrocytes exhibit robust circadian clock function(74), and clock gene deletion leads to pronounced astrocyte activation in vivo(12). Microglia also have functional circadian clocks, and the inflammatory response of microglia shows clear circadian variation(75, 86). In the periphery, the circadian clock regulates the responsiveness of macrophages to inflammatory stimuli(66), as well as monocyte trafficking to areas of inflammation(87). Rev-Erbα, a direct Bmal1 transcriptional target, regulates pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages(67). Inflammation also impacts the clock, as both Bmal1 and Rev-erbα levels are strongly suppressed in macrophages in response to the inflamogen lipopolysaccharide due to transcriptional repression by the micro RNA miR-155(68). Thus, local inflammation in the hippocampus or cortex could conceivably directly suppress Bmal1 expression in surrounding neurons and glia, leading to impaired Bmal1-mediated expression of oxidative stress response genes and rendering these cells susceptible to neurodegeneration.

Proteostasis

Neurodegenerative diseases are defined pathologically by the aggregation of certain hallmark proteins, including Aβ and tau in AD, alpha-synuclein in PD, Huntingtin in HD, and TDP-43 in some forms of ALS or Frontotemporal dementia. Degradation of misfolded proteins is a critical process in the brain, and one that goes awry in a number of disease states. DNA binding of heat shock factor 1 (Hsf1), the transcription factor that controls heat shock protein expression, exhibits robust circadian regulation, and hsf1 deletion alters circadian clock oscillation (88). Proteasomal degradation of proteins also displays circadian oscillation(89), and proteasome function is required for normal circadian clock timing(90). The clearance of pathogenic protein aggregates by autophagy has emerged as a crucial mechanism by which the brain forestalls neurodegeneration. Circadian oscillation of autophagy markers has been described in the mouse liver(91), and may be regulated by Rev-erbα (92). It is unknown if or how the circadian clock controls rhythmic protein degradation in the brain, but the implications for protein aggregation and deposition in neurodegenerative disease are clear.

The core clock regulates many other potentially neurodegenerative processes in the periphery, including NAD+ production and activation of the neuroprotective deacetylase Sirt1, both of which also feedback on clock function(93–95). It will be critical to explore these and other mechanisms in the brain and in models of neurodegeneration, with the hope of unveiling new therapeutic targets.

Therapeutic considerations

The complex interplay between the SCN, sleep-wake nuclei, and cellular circadian clocks makes dissecting the effects of this system on neurodegeneration a daunting task, but it also creates many opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Holistic methods to establish normalized day-night patterns in AD patients through combinations of morning light exposure, enforced daytime activity, consistent bed times, and evening melatonin supplementation have produced some encouraging results, and warrant further study (65, 96). However, an expanding molecular understanding of circadian and sleep systems provides new potential therapeutic targets. Pharmacologic enhancement of SCN oscillations might provide improved circadian rhythms throughout the body and brain, and at the same time normalize sleep-wake timing. Targeting orexin receptors could increase restorative sleep, decrease Aβ deposition, and may indirectly influence circadian clock function, though a negative effect of increased daytime sleepiness would have to be considered in elderly patients. Drugs which directly alter clock gene expression, activity, or oscillation at the tissue level might also be used to enhance clock-mediated transcription of protective genes. Moreover, considering that neurotransmitters including acetylcholine can influence the circadian system(97), the effect of currently-used treatments for neurodegenerative diseases (such cholinesterase inhibitors) on circadian function should be considered.

Conclusion and Future Directions

In summary, the circadian clock and the sleep wake cycle are multilayered, interconnected systems that impact brain function and neurodegeneration by multiple mechanisms. Despite great progress in understanding the basic mechanisms governing the circadian clock, as well as the neural circuitry of sleep, our knowledge of how these systems are impacted in the brain in aging and neurodegenerative disease is still rather superficial. A more detailed understanding of the mechanism by which specific neurodegenerative diseases and pathogenic proteins impact the circadian and sleep systems, as well as interplay between sleep and circadian systems in aging and neurodegeneration, is needed. While helpful, current transgenic rodent models of neurodegeneration may not fully capture the mechanistic complexity involved, and more translational methods are needed. The exact function of the core circadian clock in different brain regions and cell types is also lacking, as is knowledge of specific clock-controlled transcriptional pathways in the brain that might influence disease. The glymphatic system and its role in neurodegeneration is another area of research priority. Integrated study of clocks, sleep, and neurodegeneration is still in its infancy, but great potential exists to harness these powerful systems that govern so many critical aspects of brain function for therapeutic benefit in the prevention of neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NIH grants P01NS074969 (DMH) and 5K08NS079405 (ESM), and a New Investigator Research Grant from the Alzheimer’s Association (ESM). ESM has received consulting fees from Eisai, Inc. DMH co-founded and is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics, and consults for Genentech, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Neurophage, and Denali.

References

- 1.Videnovic A, Lazar AS, Barker RA, Overeem S. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:683–693. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.206. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatfield CF, Herbert J, van Someren EJ, Hodges JR, Hastings MH. Brain. 2004;127:1061–1074. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh129. 10.1093/brain/awh129awh129 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sterniczuk R, Theou O, Rusak B, Rockwood K. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013;10:767–775. doi: 10.2174/15672050113109990134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim AS, Kowgier M, Yu L, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Sleep. 2013;36:1027–1032. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2802. 10.5665/sleep.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schenck CH, Boeve BF, Mahowald MW. Sleep Med. 2013;14:744–748. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.009. 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:445–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bass J, Takahashi JS. Science. 2010;330:1349–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1195027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16219–16224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408886111. 10.1073/pnas.1408886111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibuka N, Kawamura H. Brain Res. 1975;96:76–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rath MF, Rohde K, Moller M. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29:1289–1299. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.728660. 10.3109/07420528.2012.728660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunger MK, et al. Cell. 2000;103:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Musiek ES, et al. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5389–5400. doi: 10.1172/JCI70317. 10.1172/JCI70317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang G, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:324ra316. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad3305. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laposky A, et al. Sleep. 2005;28:395–409. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toh KL, et al. Science. 2001;291:1040–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1057499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curie T, Maret S, Emmenegger Y, Franken P. Sleep. 2015;38:1381–1394. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4974. 10.5665/sleep.4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cedernaes J, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E1255–E1261. doi: 10.1210/JC.2015-2284. 10.1210/jc.2015-2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mongrain V, La Spada F, Curie T, Franken P. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026622. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iranzo A. Sleep Med Clin. 2016;11:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.10.011. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holth JK, Patel TK, Holtzman DM. Neurobiol Sleep Circad Rhythym. 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nbscr.2016.08.002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterniczuk R, Dyck RH, Laferla FM, Antle MC. Brain Res. 2010;1348:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudo T, Loh DH, Truong D, Wu Y, Colwell CS. Exp Neurol. 2011;232:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.003. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morton AJ, et al. J Neurosci. 2005;25:157–163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3842-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roh JH, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:150ra122. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004291. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benedict C, et al. Sleep. 2014;37:195–198. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3336. 10.5665/sleep.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frey DJ, Fleshner M, Wright KP., Jr Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.003. 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naidoo N, Ferber M, Master M, Zhu Y, Pack AI. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6539–6548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5685-07.2008. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5685-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musiek ES, Holtzman DM. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:800–806. doi: 10.1038/nn.4018. 10.1038/nn.4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang JE, et al. Science. 2009;326:1005–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1180962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y, et al. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:51–58. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.235. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roh JH, et al. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2487–2496. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141788. 10.1084/jem.20141788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benedict C, et al. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1090–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.08.104. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.08.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ju YE, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:587–593. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2334. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osorio RS, et al. Sleep. 2016;39:1253–1260. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5846. 10.5665/sleep.5846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wennstrom M, Londos E, Minthon L, Nielsen HM. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:125–132. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111655. 10.3233/jad-2012-111655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Meco A, Joshi YB, Pratico D. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:1813–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.011. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothman SM, Herdener N, Frankola KA, Mughal MR, Mattson MP. Brain Res. 2013;1529:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.07.010. 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Neuron. 2014;81:12–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.025. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mander BA, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1051–1057. doi: 10.1038/nn.4035. 10.1038/nn.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iliff JJ, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie L, et al. Science. 2013;342:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, et al. J Neurosci. 2014;34:4418–4431. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5025-12.2014. 10.1523/jneurosci.5025-12.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazar AS, et al. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:630–648. doi: 10.1002/ana.24495. 10.1002/ana.24495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kudo T, et al. Exp Neurol. 2011;228:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.12.011. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pallier PN, et al. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7869–7878. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0649-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamura TJ, et al. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10201–10205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0451-11.2011. 10.1523/jneurosci.0451-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wyse CA, Coogan AN. Brain Res. 2010;1337:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swaab DF, Fliers E, Partiman TS. Brain Res. 1985;342:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang JL, et al. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:317–322. doi: 10.1002/ana.24432. 10.1002/ana.24432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cermakian N, Lamont EW, Boudreau P, Boivin DB. J Biol Rhythms. 2011;26:160–170. doi: 10.1177/0748730410395732. 10.1177/0748730410395732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song H, et al. Mol Neurodegener. 2015;10:13. doi: 10.1186/s13024-015-0007-x. 10.1186/s13024-015-0007-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Breen DP, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:589–595. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.65. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cai Y, Liu S, Sothern RB, Xu S, Chan P. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:550–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02848.x. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maywood ES, et al. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10199–10204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1694-10.2010. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1694-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tranah GJ, et al. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:722–732. doi: 10.1002/ana.22468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen HF, Huang CQ, You C, Wang ZR, Si-qing H. Arch Med Res. 2013;44:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.01.002. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Q, Peng XD, Huang CQ, Hu XY, Zhang XM. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:18515–18522. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.23.39. 10.4238/2015.December.23.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gu Z, et al. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15891. doi: 10.1038/srep15891. 10.1038/srep15891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chaudhury D, Wang LM, Colwell CS. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:225–236. doi: 10.1177/0748730405276352. 20/3/225 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wardlaw SM, Phan TX, Saraf A, Chen X, Storm DR. Learn Mem. 2014;21:417–423. doi: 10.1101/lm.035451.114. 10.1101/lm.035451.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smarr BL, Jennings KJ, Driscoll JR, Kriegsfeld LJ. Behav Neurosci. 2014;128:283–303. doi: 10.1037/a0035963. 10.1037/a0035963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loh DH, et al. Elife. 2015;4 10.7554/eLife.09460. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uchida K, Okamoto N, Ohara K, Morita Y. Brain Res. 1996;717:154–159. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Videnovic A, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:463–469. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.6239. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.6239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riemersma-van der Lek RF, et al. JAMA. 2008;299:2642–2655. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.22.2642. 10.1001/jama.299.22.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keller M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21407–21412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gibbs JE, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:582–587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106750109. 10.1073/pnas.1106750109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Curtis AM, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:7231–7236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501327112. 10.1073/pnas.1501327112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mukherji A, Kobiita A, Ye T, Chambon P. Cell. 2013;153:812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.020. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Castanon-Cervantes O, et al. J Immunol. 2010;185:5796–5805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001026. 10.4049/jimmunol.1001026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gibson EM, Wang C, Tjho S, Khattar N, Kriegsfeld LJ. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015267. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Karatsoreos IN, Bhagat S, Bloss EB, Morrison JH, McEwen BS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1657–1662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018375108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cho K. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:567–568. doi: 10.1038/88384. 10.1038/88384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prolo LM, Takahashi JS, Herzog ED. J Neurosci. 2005;25:404–408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4133-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fonken LK, et al. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;45:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.11.009. 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ali AA, et al. Aging. 2015;7:435–449. doi: 10.18632/aging.100764. 10.18632/aging.100764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rakai BD, Chrusch MJ, Spanswick SC, Dyck RH, Antle MC. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099527. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bouchard-Cannon P, Mendoza-Viveros L, Yuen A, Kaern M, Cheng HY. Cell Rep. 2013;5:961–973. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.037. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gerstner JR, et al. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:121. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00121. 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Edgar RS, et al. Nature. 2012;485:459–464. doi: 10.1038/nature11088. 10.1038/nature11088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beaver LM, et al. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050454. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khapre RV, Kondratova AA, Susova O, Kondratov RV. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:4162–4169. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.23.18381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang TA, et al. Science. 2012;337:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1222826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koh K, Evans JM, Hendricks JC, Sehgal A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13843–13847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605903103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kondratov RV, Kondratova AA, Gorbacheva VY, Vykhovanets OV, Antoch MP. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1868–1873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1432206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hayashi Y, et al. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2744. doi: 10.1038/srep02744. 10.1038/srep02744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nguyen KD, et al. Science. 2013;341:1483–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1240636. 10.1126/science.1240636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reinke H, et al. Genes Dev. 2008;22:331–345. doi: 10.1101/gad.453808. 10.1101/gad.453808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Desvergne A, Ugarte N, Petropoulos I, Friguet B. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;75(Suppl 1):S18. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.631. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stratmann M, Suter DM, Molina N, Naef F, Schibler U. Mol Cell. 2012;48:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.012. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ma D, Panda S, Lin JD. EMBO J. 2011;30:4642–4651. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.322. 10.1038/emboj.2011.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huang G, Zhang F, Ye Q, Wang H. Autophagy. 2016;12:1292–1309. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1183843. 10.1080/15548627.2016.1183843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chang HC, Guarente L. Cell. 2013;153:1448–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.027. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nakahata Y, Sahar S, Astarita G, Kaluzova M, Sassone-Corsi P. Science. 2009;324:654–657. doi: 10.1126/science.1170803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ramsey KM, et al. Science. 2009;324:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1171641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Forbes D, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Peacock S, Hawranik P. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003946. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003946.pub4. 10.1002/14651858.CD003946.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Earnest DJ, Turek FW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4277–4281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]