Abstract

Introduction

A number of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) mediate key steps in the HIV-1 replication cycle and therefore have potential to serve as therapeutic targets for HIV-1 infection, especially in HIV-1 cure strategies. Current HIV-1 cure strategies involve the development of small molecules that are able to activate HIV-1 from latent infection, thereby allowing the immune system to recognize and clear infected cells.

Areas Covered

The role of seven CDK family members in the HIV-1 replication cycle is reviewed, with a focus on CDK9, as the mechanism whereby the viral Tat protein utilizes CDK9 to enhance viral replication is known in considerable detail.

Expert Opinion

Given the essential roles of CDKs in cellular proliferation and gene expression, small molecules that inhibit CDKs are unlikely to be feasible therapeutics for HIV-1 infection. However, small molecules that activate CDK9 and other select CDKs such as CDK11 have potential to reactivate latent HIV-1 and contribute to a functional cure of infection.

Keywords: HIV, latency, HIV cure, shock and kill, CDK, CDK9, Cyclin T1, P-TEFb, CDK11, latency reversing agents

Introduction

This review deals with the topic of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) as therapeutic targets for HIV-1 infection. To date, seven CDK family members have been shown to have important roles in HIV-1 infection. We will begin this review with a summary of the HIV-1 replication cycle, followed by a discussion of current anti-HIV-1 drugs and the need for new anti-HIV-1 therapeutics that will contribute to a functional cure of infection. This will be followed by a description of CDK properties that are significant to their roles in HIV-1 infection. We will then describe the functions of CDKs in the HIV-1 replication cycle. We will end with a discussion of which CDKs can be considered feasible targets for development of new therapeutics to treat HIV-1 infection.

1. HIV-1 replication cycle

HIV-1 infection begins when the Envelope protein of the virion binds to the CD4 receptor and CCR5 or CXCR4 co-receptor on the surface of CD4+ T cells or monocytes/macrophages, the two predominant cell types that HIV-1 infects in vivo (1). After Envelope engages the CD4 and co-receptor molecules, the virion fuses with the cellular plasma membrane and the viral core is released into the cytoplasm. The core then undergoes a regulated disassembly process that has been difficult to investigate, but the development of imaging techniques is providing important insight into this aspect of the HIV-1 replication cycle (2;3). The viral RNA genome is copied into double-strand cDNA by Reverse Transcriptase packaged in the core (4). Based upon microscopy-based single cell analysis of the MT4 cell line, completion of reverse transcription is estimated to occur at approximately 14 hours post-infection (5); it is likely that the time course of HIV-1 replication may differ in primary CD4+ T cells, especially if the cells have been subjected to limited T cell activation stimuli. The pre-integration complex containing the viral cDNA and Integrase enzyme (also packaged in the viral core) is then actively transported into the nucleus, where the cDNA is inserted into the human genome with a preference for integration into genes that are being actively transcribed (6). Active genes that are hot spots for integration are near the outer edge of the nucleus, close to nuclear pores, and integration into these genes is likely to facilitate the subsequent nuclear export of viral RNA transcribed by RNA Polymerase II (RNAP II) (7). Integration of the provirus occurs at approximately 19 hours post-infection in MT4 cells (5). The integrated viral genome is termed the provirus.

Following integration, RNAP II is directed to the viral promoter by cellular transcription factors (e.g., NFAT, NF-κB, Sp1, TFIID) that bind to their cis-regulatory sequences in the 5’ long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences of the provirus. RNAP II transcriptional initiation commences, but as described below (Section 5.D), productive transcriptional elongation is dependent on the viral Tat protein. To activate elongation, Tat binds to an RNA element at the 5’ end of nascent viral transcripts and recruits a general elongation factor termed P-TEFb. Core P-TEFb consists of CDK9 and Cyclin T1 which phosphorylate multiple substrates in the RNAP II complex and thereby activate elongation.

The primary viral transcript from the ~10,000 nucleotide proviral genome can be differentially spliced to generate multiple mature transcripts. Because incompletely spliced cellular RNAs are actively retained in the nucleus by cellular mechanisms, early viral transcripts must be spliced to remove all introns and these transcripts are exported to the cytoplasm to serve as mRNAs for early viral genes – Tat, Rev, and Nef. The onset of early viral gene expression occurs at approximately 30 hours post-infection in MT4 cells (5). The viral Rev protein contains an RNA binding-domain that binds to a highly structured RNA element, the Rev-Response Element (RRE), present in incompletely spliced viral transcripts; Rev also possesses a nuclear export signal which is bound by an export factor termed CRM1 (XPO1). This protein-RNA complex, along with the co-factor Ran-GTP, accesses a nuclear export pathway used by cellular proteins, rRNA, snRNAs, and a subset of cellular mRNAs (8). This onset of late viral gene expression is at approximately 33 hours post-infection (5). Incompletely spliced viral transcripts encode the Envelope, Vif, Vpr, and Vpu proteins. The unspliced full-length viral RNA can either serve as mRNA to produce the Gag or GagPol polyproteins, or traffic to the plasma membrane to be incorporated into new viral particles that bud from the infected cell at approximately 40 hours post-infection (5).

2. Current anti-HIV-1 drugs and need for novel therapeutics for a functional cure

There are currently over 20 FDA-approved anti-HIV-1 drugs that are grouped into five classes: Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors, Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors, Protease Inhibitors, Entry Inhibitors, and Integrase Inhibitors (9). These drugs block HIV-1 replication at different stages in the replication cycle and when used in combination – in a regime termed combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) – effectively suppress viral replication. For individuals with access to these drugs, the advent of cART in the 1990s altered HIV-1 infection from a fatal disease to a manageable chronic illness. However, cessation of cART invariably leads to the reemergence of active HIV-1 replication from a latent viral reservoir (described below). The reservoir consists of cells harboring silent replication-competent proviruses that do not express viral proteins and are therefore invisible to the immune system. Thus, HIV-infected individuals must adhere to cART for their lifetimes.

Despite its effectiveness, a number of toxicities are associated with cART – hyperlipidemia, bone loss, cardiovascular complications, neuropathy and others. These toxicities are especially problematic with the aging of the HIV-infected population (10). As a consequence of these issues with long-term cART, there is an ongoing research effort to develop therapeutic strategies to disrupt the latent viral reservoir and enhance the immune system’s ability to clear HIV-1. It is hoped that such a strategy, termed “shock and kill,” can lead to a functional cure of infection. It has been proposed that therapeutics can be developed to “shock” and thereby reactivate latent virus to express viral antigens. The “kill” involves methods to enhance the immune system’s ability to attack HIV-infected cells, perhaps the result of a therapeutic vaccine, which in combination with cART can clear reactivated virus. It is hoped that this strategy will greatly reduce the size of the reservoir, if not eliminate it, and boost the immune system of infected individuals so that viral replication can be contained without the need for continued cART, leading to a functional cure of infection.

3. HIV-1 Latent Reservoir

The best described latent reservoir is that of long-lived memory CD4+ T lymphocytes which contain a transcriptionally silent but replication-competent provirus (11). It is believed that multiple mechanisms are involved in the establishment and maintenance of latency. Transcriptional interference by cellular genes at the site of integration can contribute to latency (12;13). Repressive chromatin makes an important contribution to latency [reviewed in (14)]. Limiting levels of cellular transcription factors also make important contributions to latency, especially P-TEFb, the RNAP II elongation factor discussed above and in Sections 5D-5E below.

An active area of current HIV-1 research is the development of small molecules, termed latency reversing agents or LRAs, that can selectively reactivate latent HIV-1. This selective reactivation is an enormous challenge given that the RNAP II transcriptional apparatus which transcribes the HIV-1 provirus also transcribes all cellular protein coding genes. Additionally, latent viruses are found in a repressive chromatin configuration and LRAs must function to reverse this repression (15). It has become clear that a LRA which targets a single mechanism involved in latency is unlikely to be effective in vivo (16). Rather, multiple LRAs will likely be required to reactivate latent viruses in vivo, such as a combination of LRAs that target repressive chromatin and act as PKC agonists to up-regulate transcription factors such as NF-κB and P-TEFb (17). Many latent replication-competent proviruses are refractory to reactivation (18) and effective reactivation of latent HIV-1 may require multiple courses of LRA treatment. A recent study proposed that low doses of ionizing radiation might be used to reactivate latent HIV-1, as this method can activate proviral transcription by RNAP II and it is capable of targeting tissues that harbor latent virus (19). Additionally, a recent publication has suggested that HIV-1 replication persists in lymphoid tissues even when cART reduces levels of virus in the circulating blood to undetectable levels (20). If this publication is confirmed, strategies to reduce the viral reservoir are faced with an additional major challenge.

4. General properties of CDKs

CDKs consist of a family of 20 serine/threonine kinases [reviewed in (21)]. The catalytic activity of CDKs is dependent upon the binding of a regulatory subunit – a member of the cyclin family of proteins (although CDK5 is an exception as its regulatory subunits are not cyclins). The first CDK family members identified were found to control transitions in the cell cycle and their kinase activities were regulated by fluctuations in the level of their cyclin regulatory subunits during the cell cycle – hence the name cyclin (22). CDKs identified after the initial discovery of CDKs are not involved in the cell cycle, but function in production of RNA through regulation of RNAP II transcription or RNA processing; the cyclin subunits of these more recently identified CDKs are not cell cycle regulated. There are approximately 30 mammalian cyclins, and some CDKs utilize several different cyclins as their regulatory subunit. Cyclins are defined by the presence of a “cyclin box,” which is a structural domain of approximately 100 amino acid residues that forms a stack of five α-helices.

CDKs consist of two lobed structures, an amino-terminal lobe containing β-sheets and a carboxyl terminal lobe containing α-helices (21). The catalytic core of CDKs is sandwiched between these two lobes and it is occluded by a segment of the CDK known as the T-loop. Upon binding of a cyclin, the two CDK lobes rotate and the T-loop becomes accessible to an activating kinase – CDK7 is the activating kinase for metazoan CDKs (23). Phosphorylation of the T-loop is essential for CDK catalytic activity as it displaces the T-loop and allows substrates access to the catalytic core of the enzyme. In summary, CDK kinase activity can be turned off and on by two distinct mechanisms – the level of the regulatory cyclin subunit and phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the T-loop – and as described below, these mechanisms regulate CDK9 function in CD4+ T cells and monocytes/macrophages and this is important for both HIV-1 replication and latency.

5. CDKs involved in HIV-1 replication

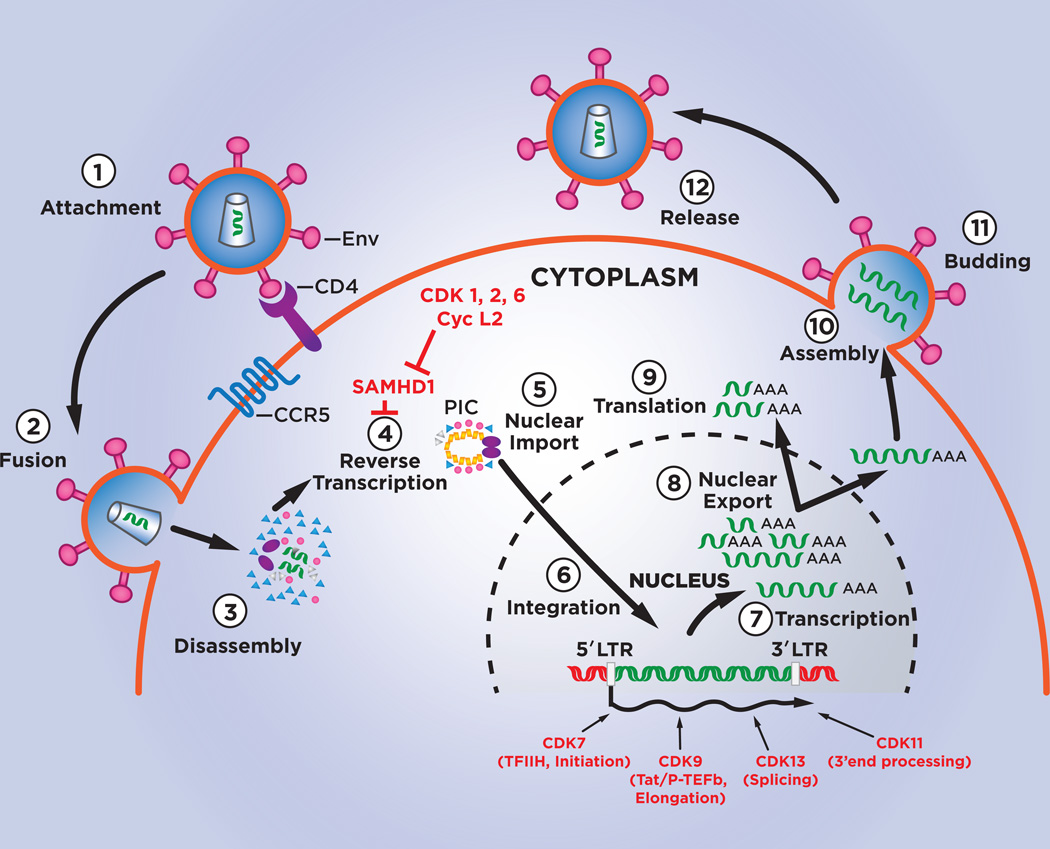

To date, seven CDK family members have been shown to have roles in the HIV-1 replication cycle. These CDKs are listed in Table 1 and their roles in the HIV-1 replication cycle are illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

CDKs involved in HIV replication.

| CDK | Role in HIV replication |

reference |

|---|---|---|

| CDK1, CDK2, CDK6,Cyclin L2 |

Inhibition of SAMHD1 |

(27–31) |

| CDK2 | Phosphorylates CDK7, CDK9, Tat |

(32–34) |

| CDK7 | RNAP II initiation of HIV-1 provirus |

(35) |

| CDK9 | RNAP II elongation of HIV-1 provirus |

Reviewed in [(37;96;97)] |

| CDK11 | HIV RNA 3’ end processing |

(87) |

| CDK13 | HIV-1 RNA splicing | (88) |

Figure 1. CDKs and the HIV-1 replication cycle.

The steps of the HIV-1 replication cycle are indicated by numbers 1 to 11. Points in the replication cycle at which CDKs and Cyclin L2 function are indicated.

5.A. CDK1, CDK2, CDK6 and SAMHD1

HIV-2 and several SIVs (simian immunodeficiency viruses) are lentiviruses closely related to HIV-1 and these viruses encode an accessory protein termed Vpx that is packaged into the virion of these lentiviruses. Early work indicated that Vpx functions to overcome an antiviral factor in non-dividing cells – monocytes and dendritic cells – which restricts replication of HIV-2 and SIV (24). This antiviral factor was subsequently identified to be a phosphohydrolase named SAMHD1 that cleaves dNTPs into deoxynucleotides and inorganic triphosphates (25;26). This activity reduces the levels of dNTPs needed for reverse transcription and thus blocks HIV-2/SIV replication at the cDNA synthesis stage. Vpx overcomes the antiviral activity of SAMHD1 by targeting it for proteasome-mediated proteolysis.

The identification of SAMHD1 as the target of HIV-2/SIV Vpx raised a conundrum, as SAMHD1 is expressed at high levels in activated CD4+ T cells and monocytic cells lines, and these proliferating cells support robust HIV-1 replication despite the absence of Vpx in the HIV-1 genome. How is HIV-1 able to complete reverse transcription in these cells in the presence of high levels of SAMHD1? This puzzle was solved when it was found that CDKs activated during the cell cycle of proliferating cells – CDK1, CDK2, and CDK6 – inactivate SAMHD1 through the phosphorylation of threonine 592 in the SAMHD1 protein (27–30). Thus, CDK1, CDK2, and CDK6 act to stimulate HIV-1 reverse transcription in activated CD4+ T cells and transformed cell lines through an inactivating phosphorylation of the antiviral factor SAMHD1. Additionally, Cyclin L2, a regulatory partner for CDK11, has been shown to interact with SAMHD1 in macrophages and target the antiviral protein for proteasome-mediated degradation, thereby enhancing HIV-1 replication in this cell type (31).

5.B. Additional CDK2 substrates

CDK2 has been reported to phosphorylate and thereby regulate the activity of a number of proteins involved in HIV-1 replication, including CDK7, CDK9, and the viral Tat protein (32–34). The phosphorylation of each of the proteins is reported to enhance RNAP II transcription of the HIV-1 provirus.

5.C. CDK7 and RNAP II initiation

CDK7 is a subunit of a general RNAP II transcription factor known as TFIIH. This CDK family member activates transcriptional initiation through phosphorylation of the carboxyl terminal domain (CTD) of the large subunit of RNAP II. The CTD of the human protein contains 52 heptad repeats of the consensus sequence YSPTSPS and CDK7 predominantly phosphorylates the S5 residue of this repeat. As RNAP II transcribes the integrated HIV-1 provirus, CDK7 plays a direct role in transcriptional initiation of the HIV-1 genome. Under some conditions, recruitment of CDK7 in the TFIIH complex can be a rate-limiting step in reactivation of HIV-1 from latency (35). Although some early studies suggested that CDK7 may be involved in HIV-1 Tat protein stimulation of RNAP II elongation, subsequent studies clearly established CDK9 as the CDK family member involved in Tat function.

5.D. CDK9 and RNAP II elongation

This CDK family member has perhaps the most direct role in the HIV-1 replication cycle, as CDK9 and its cyclin partner, Cyclin T1, are directly bound by the viral Tat protein. Indeed, a crystal structure of a Tat/CDK9/Cyclin T1 complex has been determined (36). Although RNAP II initiates transcription of the HIV-1 provirus at a relatively high basal rate as described above, transcriptional elongation is defective due to the action of two negative factors that associate with the RNAP II complex – DSIF (DRB Sensitivity Inducing Factor, consists of two protein subunits) and NELF (Negation Elongation Factor consists of five protein subunits) (37). Also as described above, CDK9 and Cyclin T1 constitute the RNAP II elongation factor termed P-TEFb. Tat overcomes the defect in RNAP II elongation of the provirus by binding along with CDK9/Cyclin T1 to an RNA element termed TAR RNA that forms at the 5’ ends of nascent HIV-1 transcripts. CDK9 then phosphorylates subunits of both DSIF and NELF and thereby counters their negative function; CDK9 also phosphorylates Ser2 in the RNAP II CTD and this is associated with activation of elongation.

Biochemical studies have shown that P-TEFb exists in three distinct complexes [reviewed in (38)]. The first complex is “Core P-TEFb” and it is composed of CDK9, CyclinT1, and Brd4; Brd4 contains two bromodomains which bind to histone acetyl-lysine residues in active chromatin. The second P-TEFb complex is the “Super Elongation Complex” (SEC) composed of CDK9, Cyclin T1, ELL1/ELL2, AFF4, and ENL/AF9. The third P-TEFb complex is the “7SK RNP” and it is composed of 7SK RNA, CDK9, Cyclin T1, HEXIM1/2, LARP7, and MEPCE; CDK9 is not catalytically active in the 7SK RNP. In rapidly dividing and metabolically active cells, such as transformed cell lines or activated CD4+ T cells, a large portion of P-TEFb (perhaps up to 90%) is found in the 7SK RNP (39). Cyclin T2 is an additional minor regulatory partner of CDK9 (40). Cyclin T2 is encoded by a distinct gene and is expressed at significantly lower levels than Cyclin T1 in all tissues and cell lines examined to date. The abundance of Cyclin T2 in the various P-TEFb complexes is therefore considerably lower than that of Cyclin T1.

Tat can utilize CDK9/Cyclin T1 in each of the three P-TEFb complexes by binding directly to CDK9 and Cyclin T1. Tat utilizes the Core P-TEFb complex by displacing Brd4 from CDK9/Cyclin T1 (41). A thienotriazolodiazepine termed JQ1 is an inhibitor of Brd4 and it can enhance RNAP II transcription and reactivation of the HIV-1 provirus by displacing Brd4 from Core P-TEFb, thereby presumably increasing the pool of P-TEFb that can activate RNAP II elongation (42–45). Tat can associate with the SEC and stabilize this P-TEFb complex to potently activate viral gene expression (46;47). Tat can extract active CDK9/Cyclin T1 from the 7SK RNP (48–50). Recent evidence indicates that the 7SK RNP can be recruited to the HIV-1 promoter and following transcription of the TAR RNA element, Tat can extract Cyclin T1/CDK9 to activate transcriptional elongation (51;52). However, it is somewhat controversial whether the 7SK RNP is recruited to the LTR upstream of the transcriptional start site, as some chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses indicate that CDK9/Cyclin T1 is recruited to the HIV-1 LTR via TAR RNA and not HIV-1 promoter elements (53).

5.E. Regulation of CDK9 (P-TEFb) in cells relevant to HIV-1 infection

CDK9 and Cyclin T1 are highly regulated in CD4+ T cells and monocytes/macrophages and this is important for both HIV-1 replication and latency.

CD4+ T cells

In resting CD4+ T cells isolated from healthy blood donors, Cyclin T1 protein levels are low and cellular activation up-regulates Cyclin T1 by a post-transcriptional mechanism (54–56). Cyclin T2, the alternative regulatory subunit of CDK9 that is not targeted by the HIV-1 Tat protein, is expressed at a basal level in resting CD4+ T cells and is generally not induced following T cell activation (55;57); the basal expression of Cyclin T2 may supply the minimal requirements for P-TEFb in resting CD4+ cells. SiRNA depletion experiments have shown that the up-regulation of Cyclin T1 in activated CD4+ T cells is required for Tat activation of the viral LTR, as well as induction of a large portion of mRNAs induced by T cell activation (54;58). Four miRNAs have been identified that are expressed at high levels in resting CD4+ T cells and repress translation of Cyclin T1 mRNA in these cells: miR-27b, miR-29b, miR-150, and miR-223 (59). Importantly, agents that only minimally activate resting CD4+ T cells, such as a combination of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6) or prostratin, can up-regulate Cyclin T1 and CDK9 kinase activity without inducing T cell proliferation or T cell activation markers (54;56). This indicates that it may be possible to selectively up-regulate P-TEFb activity in resting CD4+ T cells without generalized immune activation. This important concept is discussed below in the Expert Opinion section.

Unlike Cyclin T1, CDK9 is generally expressed at a high basal level in resting CD4+ T cells (54;60). However, phosphorylation of threonine 186 in CDK9’s T-loop is low to absent in resting CD4+ T cells and CDK9 enzymatic activity is correspondingly low (61). Upon T cell activation, there is a rapid phosphorylation of CDK9’s T-loop (61). Recent work has demonstrated that CDK7 is a kinase responsible for phosphorylating the CDK9 T-loop (62). The phosphatase PPM1A has been shown to regulate T-loop dephosphorylation in CD4+ T cells, as siRNA depletion of PPM1A in resting CD4+ T cells leads to elevated T-loop phosphorylation and enhanced HIV-1 gene expression (63). Three other phosphatases have been shown to be capable of dephosphorylating the CDK9 T-loop in transformed cell lines: PP2B, PP1α, PPM1G (52;64). The relative importance of these three additional CDK9 T-loop phosphatases in primary CD4+ T cells is not known. CDK9 is also phosphorylated on Ser175 upon activation of resting CD4+ T cells and molecular modeling suggests that this modification strengthens the interactions between CDK9 and Tat (65). The kinase and phosphatases that regulate Ser175 phosphorylation are not known.

Monocytes/macrophages

In monocytes isolated from healthy blood donors, Cyclin T1 levels are low and are up-regulated as the cells differentiate to macrophages (66;67). MiR-198 has been identified as a miRNA that represses Cyclin T1 protein expression in monocytes (68). Similar to resting CD4+ T cells, CDK9 T-loop phosphorylation is low in monocytes and it is up-regulated during macrophage differentiation (67). Upon extended culture time for primary macrophages, the Cyclin T1 protein that was induced during differentiation is shut-off by proteasome-mediated proteolysis (66), and this shut-off of Cyclin T1 can be accelerated by IL-10 (69). After the shut-off in late-differentiated macrophages, Cyclin T1 can be re-induced through post-transcriptional mechanisms by activation with pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or HIV-1 infection (70;71).

7SK RNP

The 7SK P-TEFb complex is present at very low levels in resting CD4+ T cells and monocytes, reflecting the low levels Cyclin T1 and CDK9 T-loop phosphorylation (54;72–74). Given that the 7SK RNP is recruited directly to cellular enhancers and promoters to activate RNAP II elongation of cellular genes (75;76), the low level of the 7SK RNP likely reflects the minimal requirements of RNAP II transcription elongation in resting CD4+ T cells and monocytes. Upon T cell activation or induction of macrophage differentiation, there is a large increase in the amount and proportion of Cyclin T1/CDK9 in the 7SK complex (54;73;74). The 7SK complex is concentrated near nuclear “speckles,” a nuclear structure where P-TEFb and splicing factors have been proposed to be assembled during cycles of transcription and RNA processing (77).

The kinase activity of CDK9 is repressed in the 7SK RNP through its association with HEXIM1/2 and the 7SK RNP is consequently a negative regulator of P-TEFb kinase activity (78–80). Signaling pathways have been identified in CD4+ T cells that when activated cause release of Core P-TEFb from the 7SK RNP and the subsequent activation of HIV-1 proviral transcription. T-cell receptor stimulation of Jurkat CD4+ T cell leads to dissociation of CDK9 and Cyclin T1 from the 7SK RNP and reactivation of a latent HIV-1 provirus (53). Activation of PKC can also lead to dissociation of Core P-TEFb and activation of proviral transcription (81). Recent work has shown that the phosphatase PPM1G can associate with the 7SK RNP and dephosphorylate the CDK9 T-loop, resulting in release of Core P-TEFb in which the T-loop is phosphorylated by CDK7 to activate RNAP II elongation (83). Non-physiological stimuli, such as Actinomycin D, UV irradiation, or Hexamethylene bisacetamide (HMBA) can release Core P-TEFb and activate HIV-1 proviral transcription (79;80;84).

5.F. CDK11

This CDK family member was observed to require Cyclin T1 for its transcriptional induction in activated CD4+ T cells, and siRNA depletions demonstrated that CDK11 has a positive role in HIV-1 proviral gene expression (58). Additionally, a genetic screen identified an amino terminal fragment of the eukaryotic translational initiation factor eIF3 as an inhibitor of HIV-1 RNA 3’ end processing (85). As eIF3 was known to interact with CDK11 (86), subsequent work found that CDK11 has a critical role in processing the 3’ end of HIV-1 RNA. A recent publication has provided insight into the mechanism involved in CDK11 regulation of HIV-1 3’ end processing (87). A multiprotein complex termed TREX/THOC couples the processes of RNAP II transcriptional elongation, RNA processing, and nuclear export. CDK11 was found to associate with TREX/THOC and facilitate HIV-1 RNA 3’ end processing (87). When recruited to the transcribed integrated provirus via TREX/THOC, CDK11 phosphorylates Ser2 in the RNAP CTD and this increases cleavage and polyadenylated of the 3’ end of the proviral transcript.

5.G. CDK13

This CDK family member was reported to associate with the Tat protein when the viral protein is acetylated in its RNA-binding domain (88). This association of CDK13 with acetylated Tat is proposed to inhibit CDK13 involvement in RNA splicing, thereby leading to an increase in unspliced and incompletely spliced viral transcripts.

6. Expert Opinion

Although the CDKs described above have important roles in the HIV-1 replication cycle, they have essential roles in cellular proliferation and gene expression. Small molecules that inhibit these kinases are likely to be cytotoxic and therefore are not feasible as anti-HIV-1 therapeutics. Indeed, current anti-HIV-1 drugs are quite effective and their use in cART regimes has limited the generation of drug-resistant viruses. If such viruses do arise, future drug development will almost certainly be directed towards deriving new small molecules that belong to one of the current five classes of anti-HIV-1 drugs.

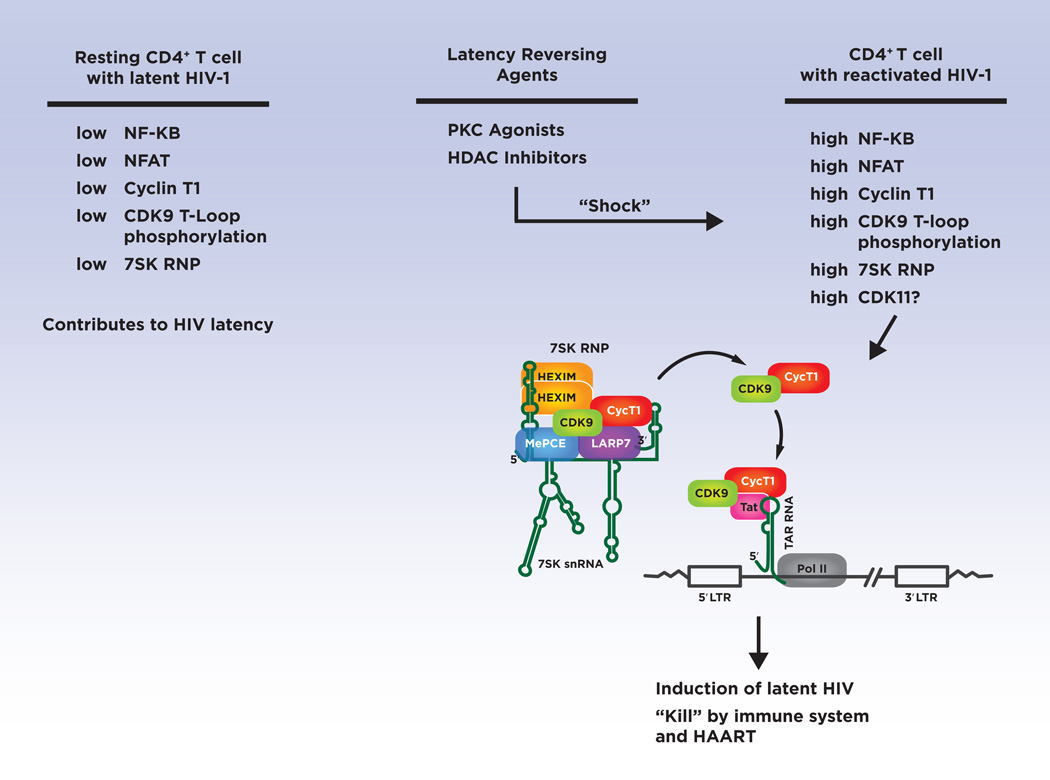

Although inhibitors of CDKs do not appear to be realistic therapeutics to treat HIV-1 infection, small molecules that activate select CDKs in resting CD4+ T cells have therapeutic potential as LRAs (see Figure 2). These small molecules have potential to “shock” HIV-1 proviruses out of transcriptional latency and contribute to a functional cure of infection. A key cellular factor that must be up-regulated by the “shock” is CDK9/P-TEFb (see section 5.E above), as its induction in resting CD4+ T cells is essential to reactivate latent viruses (89). It is critical that LRAs which induce CDK9/P-TEFb do not lead to generalized immune activation. Fortunately this is likely to be achievable as a combination of cytokines (TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6) or the PKC agonist prostratin have been shown to induce CDK9/P-TEFb activity in resting CD4+ T cells without inducing the T cell activation marker CD25 or cellular proliferation (54;56). A synthetic prostratin derivative has been developed recently which is potent in reactivating latent HIV-1 in patient cells ex vivo and also does not induce significant levels of CD25 (90). Additional PKC agonists termed Ingenol esters have been shown recently to effectively reactivate latent HIV-1 in patient cells ex vivo and also up-regulate CDK9/P-TEFb (91–93). An important component of the “shock” is for an LRA to possess an activity that can relieve repressive chromatin, such as LRAs that function as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) (15). Interestingly, broad spectrum HDACis (vorinostat and panobinostat) that reactivate latent HIV-1 through relief of repressive chromatin also up-regulate CDK9/P-TEFb through elevated levels of T-loop phosphorylation, suggesting that some HDACis have multiple mechanisms of action as LRAs (94;95).

Figure 2. Targets of Latency Reversing Agents.

Cellular factors limiting for HIV-1 replication in latently-infected resting CD4+ T cells are indicated in the left column. LRAs are needed to be developed that can “shock” latently-infected cells and up-regulate the cellular factors shown in the right column. A key cellular factor that must be up-regulated by LRAs is P-TEFb, shown in the 7SK RNP (see text). The mechanism by which P-TEFb (CDK9/Cyclin T1) is utilized by the viral Tat protein to activate RNAP II elongation of the HIV-1 provirus is indicated.

In the future, high-throughput screens for small molecules that up-regulate CDK/P-TEFb in resting CD4+ T cells can be used in efforts to develop novel LRAs. Microscopy-based assays with antisera against Cyclin T1 and the CDK9 T-loop have potential to develop robust assays for such screens. Additionally, release of Core P-TEFb from the 7SK RNP contributes to an increase in RNAP II elongation of the HIV-1 proviruses, and therefore small molecules that stimulate this release have potential as LRAs. Finally, the recent identification of CDK11 as a cellular factor essential in 3’ processing of the primary HIV-1 transcript is an important finding (87). It is not known if CDK11 is limiting for reactivation of latent HIV-1 and this is therefore a question for future studies. If CDK11 is a limiting factor for HIV-1 reactivation, studies of the mechanisms that regulate this CDK family member in CD4+ T cells will be insightful. Similar to CDK9, CDK11 may serve as a useful target in “shock and kill” strategies to clear or reduce the latent HIV-1 reservoir.

Highlights.

The HIV-1 replication cycle

Seven CDK family members are involved in the HIV-1 replication cycle

CDK9 and Cyclin T1 comprise a factor named P-TEFb that mediates HIV-1 Tat protein activation of RNAP II elongation of the integrated HIV-1 provirus

CDK9/P-TEFb is down-regulated in CD4+ T cells that harbor latent HIV-1 and this CDK must be up-regulated for the activation of latent viruses

The development of small molecules that activate CDK9/P-TEFb have potential in HIV-1 cure strategies

CDK11 has recently been shown to be essential in the 3’ end processing of the HIV-1 RNA genome and future studies are needed to determine if this CDK family member is a feasible target for HIV cure strategies

Acknowledgments

I thank Carolyn Rice for comments on the manuscript.

Declarations

Research carried out in A. Rice’s laboratory has been supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI116173, AI124866 and P30AI1036211 (Baylor-UT Houston Center for AIDS Research). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding

This paper was not funded

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Weiss RA. Thirty years on: HIV receptor gymnastics and the prevention of infection. BMC Biol. 2013;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambrose Z, Aiken C. HIV-1 uncoating: connection to nuclear entry and regulation by host proteins. Virology. 2014 Apr;454–455:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Francis AC, Marin M, Shi J, Aiken C, Melikyan GB. Time-Resolved Imaging of Single HIV-1 Uncoating In Vitro and in Living Cells. PLoS Pathog. 2016 Jun;12(6):e1005709. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005709. •• This publication describes an imaging study that provided important insight into the HIV-1 uncoating process in cells.

- 4.Hu WS, Hughes SH. HIV-1 reverse transcription. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Oct;2(10) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holmes M, Zhang F, Bieniasz PD. Single-Cell and Single-Cycle Analysis of HIV-1 Replication. PLoS Pathog. 2015 Jun;11(6):e1004961. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004961. • This publication provides a time line for key steps in the HIV-1 replication cycle in a CD4+ T cell line.

- 6.Craigie R, Bushman FD. HIV DNA integration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Jul;2(7):a006890. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marini B, Kertesz-Farkas A, Ali H, Lucic B, Lisek K, Manganaro L, et al. Nuclear architecture dictates HIV-1 integration site selection. Nature. 2015 May 14;521(7551):227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature14226. • This publication presented evidence that HIV-1 integration into active cellular genes has a preference for genes near the outer edge of the nucleus, close to nuclear pores.

- 8.Sloan KE, Gleizes PE, Bohnsack MT. Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of RNAs and RNA-Protein Complexes. J Mol Biol. 2016 May 22;428(10 Pt A):2040–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De CE, Li G. Approved Antiviral Drugs over the Past 50 Years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016 Jul;29(3):695–747. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jourjy J, Dahl K, Huesgen E. Antiretroviral Treatment Efficacy and Safety in Older HIV-Infected Adults. Pharmacotherapy. 2015 Dec;35(12):1140–1151. doi: 10.1002/phar.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. A long-term latent reservoir for HIV-1: discovery and clinical implications. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004 Jul;54(1):6–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenasi T, Contreras X, Peterlin BM. Transcriptional interference antagonizes proviral gene expression to promote HIV latency. Cell Host Microbe. 2008 Aug 14;4(2):123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shan L, Yang HC, Rabi SA, Bravo HC, Shroff NS, Irizarry RA, et al. Influence of host gene transcription level and orientation on HIV-1 latency in a primary-cell model. J Virol. 2011 Jun;85(11):5384–5393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02536-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakre S, Chavez L, Shirakawa K, Verdin E. Epigenetic regulation of HIV latency. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011 Jan;6(1):19–24. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283412384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lusic M, Giacca M. Regulation of HIV-1 latency by chromatin structure and nuclear architecture. J Mol Biol. 2015 Feb 13;427(3):688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bullen CK, Laird GM, Durand CM, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. New ex vivo approaches distinguish effective and ineffective single agents for reversing HIV-1 latency in vivo. Nat Med. 2014 Apr;20(4):425–429. doi: 10.1038/nm.3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. Recent developments in the search for a cure for HIV-1 infection: targeting the latent reservoir for HIV-1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Jul;134(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho YC, Shan L, Hosmane NN, Wang J, Laskey SB, Rosenbloom DI, et al. Replication-competent noninduced proviruses in the latent reservoir increase barrier to HIV-1 cure. Cell. 2013 Oct 24;155(3):540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iordanskiy S, Kashanchi F. Potential of Radiation-Induced Cellular Stress for Reactivation of Latent HIV-1 and Killing of Infected Cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016 Feb;32(2):120–124. doi: 10.1089/aid.2016.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorenzo-Redondo R, Fryer HR, Bedford T, Kim EY, Archer J, Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. Persistent HIV-1 replication maintains the tissue reservoir during therapy. Nature. 2016 Feb 4;530(7588):51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature16933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malumbres M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014;15(6):122. doi: 10.1186/gb4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans T, Rosenthal ET, Youngblom J, Distel D, Hunt T. Cyclin: a protein specified by maternal mRNA in sea urchin eggs that is destroyed at each cleavage division. Cell. 1983 Jun;33(2):389–396. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher RP. The CDK Network: Linking Cycles of Cell Division and Gene Expression. Genes Cancer. 2012 Nov;3(11–12):731–738. doi: 10.1177/1947601912473308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fletcher TM, III, Brichacek B, Sharova N, Newman MA, Stivahtis G, Sharp PM, et al. Nuclear import and cell cycle arrest functions of the HIV-1 Vpr protein are encoded by two separate genes in HIV-2/SIV(SM) EMBO J. 1996 Nov 15;15(22):6155–6165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, et al. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011 Jun 30;474(7353):658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Segeral E, et al. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011 Jun 30;474(7353):654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White TE, Brandariz-Nunez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen LA, Kim B, et al. The retroviral restriction ability of SAMHD1, but not its deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity, is regulated by phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe. 2013 Apr 17;13(4):441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadao AL, Laguette N, Benkirane M. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep. 2013 Apr 25;3(4):1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pauls E, Ruiz A, Badia R, Permanyer M, Gubern A, Riveira-Munoz E, et al. Cell cycle control and HIV-1 susceptibility are linked by CDK6-dependent CDK2 phosphorylation of SAMHD1 in myeloid and lymphoid cells. J Immunol. 2014 Aug 15;193(4):1988–1997. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.St GC, de SS, Hach JC, White TE, Diaz-Griffero F, Yount JS, et al. Identification of cellular proteins interacting with the retroviral restriction factor SAMHD1. J Virol. 2014 May;88(10):5834–5844. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00155-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyei GB, Cheng X, Ramani R, Ratner L. Cyclin L2 Is a Critical HIV Dependency Factor in Macrophages that Controls SAMHD1 Abundance. Cell Host Microbe. 2015 Jan 14;17(1):98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nekhai S, Zhou M, Fernandez A, Lane WS, Lamb NJ, Brady J, et al. HIV-1 Tat-associated RNA polymerase C-terminal domain kinase, CDK2, phosphorylates CDK7 and stimulates Tat-mediated transcription. Biochem J. 2002 Jun 15;364(Pt 3):649–657. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ammosova T, Berro R, Jerebtsova M, Jackson A, Charles S, Klase Z, et al. Phosphorylation of HIV-1 Tat by CDK2 in HIV-1 transcription. Retrovirology. 2006;3:78. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breuer D, Kotelkin A, Ammosova T, Kumari N, Ivanov A, Ilatovskiy AV, et al. CDK2 regulates HIV-1 transcription by phosphorylation of CDK9 on serine 90. Retrovirology. 2012;9:94. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim YK, Bourgeois CF, Pearson R, Tyagi M, West MJ, Wong J, et al. Recruitment of TFIIH to the HIV LTR is a rate-limiting step in the emergence of HIV from latency. EMBO J. 2006 Aug 9;25(15):3596–3604. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tahirov TH, Babayeva ND, Varzavand K, Cooper JJ, Sedore SC, Price DH. Crystal structure of HIV-1 Tat complexed with human P-TEFb. Nature. 2010 Jun 10;465(7299):747–751. doi: 10.1038/nature09131. •• This publication presented for the first time the crystal structure of Tat bound to P-TEFb.

- 37.Zhou Q, Li T, Price DH. RNA polymerase II elongation control. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:119–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052610-095910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith E, Lin C, Shilatifard A. The super elongation complex (SEC) and MLL in development and disease. Genes Dev. 2011 Apr 1;25(7):661–672. doi: 10.1101/gad.2015411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gudipaty SA, D’Orso I. Functional interplay between PPM1G and the transcription elongation machinery. RNA Dis. 2016;3(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng J, Zhu Y, Milton JT, Price DH. Identification of multiple cyclin subunits of human P-TEFb. Genes Dev. 1998;12(5):755–762. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bisgrove DA, Mahmoudi T, Henklein P, Verdin E. Conserved P-TEFb-interacting domain of BRD4 inhibits HIV transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Aug 21;104(34):13690–13695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705053104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Z, Guo J, Wu Y, Zhou Q. The BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 activates HIV latency through antagonizing Brd4 inhibition of Tat-transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Oct 18; doi: 10.1093/nar/gks976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banerjee C, Archin N, Michaels D, Belkina AC, Denis GV, Bradner J, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a novel strategy for reactivation of HIV-1. J Leukoc Biol. 2012 Dec;92(6):1147–1154. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0312165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu J, Gaiha GD, John SP, Pertel T, Chin CR, Gao G, et al. Reactivation of latent HIV-1 by inhibition of BRD4. Cell Rep. 2012 Oct 25;2(4):807–816. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boehm D, Calvanese V, Dar RD, Xing S, Schroeder S, Martins L, et al. BET bromodomain-targeting compounds reactivate HIV from latency via a Tat-independent mechanism. Cell Cycle. 2012 Feb 1;12(3) doi: 10.4161/cc.23309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He N, Liu M, Hsu J, Xue Y, Chou S, Burlingame A, et al. HIV-1 Tat and host AFF4 recruit two transcription elongation factors into a bifunctional complex for coordinated activation of HIV-1 transcription. Mol Cell. 2010 May 14;38(3):428–438. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sobhian B, Laguette N, Yatim A, Nakamura M, Levy Y, Kiernan R, et al. HIV-1 Tat assembles a multifunctional transcription elongation complex and stably associates with the 7SK snRNP. Mol Cell. 2010 May 14;38(3):439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sedore SC, Byers SA, Biglione S, Price JP, Maury WJ, Price DH. Manipulation of P-TEFb control machinery by HIV: recruitment of P-TEFb from the large form by Tat and binding of HEXIM1 to TAR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(13):4347–4358. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barboric M, Yik JH, Czudnochowski N, Yang Z, Chen R, Contreras X, et al. Tat competes with HEXIM1 to increase the active pool of P-TEFb for HIV-1 transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007 Mar 6; doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulte A, Czudnochowski N, Barboric M, Schonichen A, Blazek D, Peterlin BM, et al. Identification of a cyclin T-binding domain in Hexim1 and biochemical analysis of its binding competition with HIV-1 Tat. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jul 1;280(26):24968–24977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D’Orso I, Jang GM, Pastuszak AW, Faust TB, Quezada E, Booth DS, et al. Transition Step during Assembly of HIV Tat:P-TEFb Transcription Complexes and Transfer to TAR RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2012 Dec;32(23):4780–4793. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00206-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McNamara RP, McCann JL, Gudipaty SA, D’Orso I. Transcription factors mediate the enzymatic disassembly of promoter-bound 7SK snRNP to locally recruit P-TEFb for transcription elongation. Cell Rep. 2013 Dec 12;5(5):1256–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim YK, Mbonye U, Hokello J, Karn J. T-cell receptor signaling enhances transcriptional elongation from latent HIV proviruses by activating P-TEFb through an ERK-dependent pathway. J Mol Biol. 2011 Jul 29;410(5):896–916. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sung TL, Rice AP. Effects of prostratin on Cyclin T1/P-TEFb function and the gene expression profile in primary resting CD4+ T cells. Retrovirology. 2006;3:66. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herrmann CH, Carroll RG, Wei P, Jones KA, Rice AP. Tat-associated kinase, TAK, activity is regulated by distinct mechanisms in peripheral blood lymphocytes and promonocytic cell lines. J Virol. 1998 Dec;72(12):9881–9888. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9881-9888.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghose R, Liou LY, Herrmann CH, Rice AP. Induction of TAK (cyclin T1/P-TEFb) in purified resting CD4(+) T lymphocytes by combination of cytokines. J Virol JID - 0113724. 2001 Dec;75(23):11336–11343. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11336-11343.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu H, Herrmann CH. Differential localization and expression of the Cdk9 42k and 55k isoforms. J Cell Physiol. 2005 Apr;203(1):251–260. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu W, Ramakrishnan R, Wang Y, Chiang K, Sung TL, Rice AP. Cyclin T1-dependent genes in activated CD4 T and macrophage cell lines appear enriched in HIV-1 co-factors. PLoS ONE. 2008 Sep 5;3(9):e3146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chiang K, Sung TL, Rice AP. Regulation of Cyclin T1 and HIV-1 Replication by MicroRNAs in Resting CD4+ T Lymphocytes. J Virol. 2012 Mar;86(6):3244–3252. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05065-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haaland RE, Herrmann CH, Rice AP. Increased association of 7SK snRNA with Tat cofactor P-TEFb following activation of peripheral blood lymphocytes. AIDS. 2003 Nov 21;17(17):2429–2436. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramakrishnan R, Dow EC, Rice AP. Characterization of Cdk9 T-loop phosphorylation in resting and activated CD4(+) T lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2009 Dec;86(6):1345–1350. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0509309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larochelle S, Amat R, Glover-Cutter K, Sanso M, Zhang C, Allen JJ, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase control of the initiation-to-elongation switch of RNA polymerase II. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012 Nov;19(11):1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Budhiraja S, Ramakrishnan R, Rice AP. Phosphatase PPM1A negatively regulates P-TEFb function in resting CD4T+ T cells and inhibits HIV-1 gene expression. Retrovirology. 2012;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen R, Liu M, Li H, Xue Y, Ramey WN, He N, et al. PP2B and PP1alpha cooperatively disrupt 7SK snRNP to release P-TEFb for transcription in response to Ca2+ signaling. Genes Dev. 2008 May 15;22(10):1356–1368. doi: 10.1101/gad.1636008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mbonye UR, Gokulrangan G, Datt M, Dobrowolski C, Cooper M, Chance MR, et al. Phosphorylation of CDK9 at Ser175 enhances HIV transcription and is a marker of activated P-TEFb in CD4(+) T lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2013 May;9(5):e1003338. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liou LY, Herrmann CH, Rice AP. Transient induction of cyclin T1 during human macrophage differentiation regulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat transactivation function. J Virol. 2002 Nov;76(21):10579–10587. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10579-10587.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dong C, Kwas C, Wu L. Transcriptional restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gene expression in undifferentiated primary monocytes. J Virol. 2009 Apr;83(8):3518–3527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02665-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sung TL, Rice AP. miR-198 inhibits HIV-1 gene expression and replication in monocytes and its mechanism of action appears to involve repression of cyclin T1. PLoS Pathog. 2009 Jan;5(1):e1000263. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y, Rice AP. Interleukin-10 inhibits HIV-1 LTR-directed gene expression in human macrophages through the induction of cyclin T1 proteolysis. Virology. 2006 Sep 1;352(2):485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liou LY, Herrmann CH, Rice AP. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection induces cyclin T1 expression in macrophages. J Virol. 2004 Aug;78(15):8114–8119. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8114-8119.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liou LY, Haaland RE, Herrmann CH, Rice AP. Cyclin T1 but not cyclin T2a is induced by a post-transcriptional mechanism in PAMP-activated monocyte-derived macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2006 Feb;79(2):388–396. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0805429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haaland RE, Herrmann CH, Rice AP. Increased association of 7SK snRNA with Tat cofactor P-TEFb following activation of peripheral blood lymphocytes. AIDS. 2003 Nov 21;17(17):2429–2436. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Budhiraja S, Famiglietti M, Bosque A, Planelles V, Rice AP. Cyclin T1 and CDK9 T-Loop Phosphorylation Are Downregulated during Establishment of HIV-1 Latency in Primary Resting Memory CD4+ T Cells. J Virol. 2013 Jan;87(2):1211–1220. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02413-12. • This publication demonstrated that P-TEFb is down-regulated as HIV-1 latency is established in a primary CD4+ T cell model of latency.

- 74.Bartholomeeusen K, Fujinaga K, Xiang Y, Peterlin BM. HDAC inhibitors that release Positive Transcription Elongation Factor b (P-TEFb) from its Inhibitory Complex also activate HIV Transcription. J Biol Chem. 2013 Mar 28; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.464834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu W, Ma Q, Wong K, Li W, Ohgi K, Zhang J, et al. Brd4 and JMJD6-associated anti-pause enhancers in regulation of transcriptional pause release. Cell. 2013 Dec 19;155(7):1581–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ji X, Zhou Y, Pandit S, Huang J, Li H, Lin CY, et al. SR proteins collaborate with 7SK and promoter-associated nascent RNA to release paused polymerase. Cell. 2013 May 9;153(4):855–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dow EC, Liu H, Rice AP. T-loop phosphorylated Cdk9 localizes to nuclear speckle domains which may serve as sites of active P-TEFb function and exchange between the Brd4 and 7SK/HEXIM1 regulatory complexes. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22096. In the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fujinaga K, Luo Z, Peterlin BM. Genetic analysis of the structure and function of 7SK small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) in cells. J Biol Chem. 2014 Jul 25;289(30):21181–21190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.557751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang Z, Zhu Q, Luo K, Zhou Q. The 7SK small nuclear RNA inhibits the CDK9/cyclin T1 kinase to control transcription. Nature JID - 0410462. 2001 Nov 15;414(6861):317–322. doi: 10.1038/35104575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nguyen VT, Kiss T, Michels AA, Bensaude O. 7SK small nuclear RNA binds to and inhibits the activity of CDK9/cyclin T complexes. Nature JID - 0410462. 2001 Nov 15;414(6861):322–325. doi: 10.1038/35104581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fujinaga K, Barboric M, Li Q, Luo Z, Price DH, Peterlin BM. PKC phosphorylates HEXIM1 and regulates P-TEFb activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Oct;40(18):9160–9170. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cary DC, Fujinaga K, Peterlin BM. Molecular mechanisms of HIV latency. J Clin Invest. 2016 Feb;126(2):448–454. doi: 10.1172/JCI80565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gudipaty SA, McNamara RP, Morton EL, D’Orso I. PPM1G Binds 7SK RNA and Hexim1 To Block P-TEFb Assembly into the 7SK snRNP and Sustain Transcription Elongation. Mol Cell Biol. 2015 Nov;35(22):3810–3828. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00226-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Contreras X, Barboric M, Lenasi T, Peterlin BM. HMBA releases P-TEFb from HEXIM1 and 7SK snRNA via PI3K/Akt and activates HIV transcription. PLoS Pathog. 2007 Oct 12;3(10):1459–1469. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Valente ST, Gilmartin GM, Mott C, Falkard B, Goff SP. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by eIF3f. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Mar 17;106(11):4071–4078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900557106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shi J, Feng Y, Goulet AC, Vaillancourt RR, Sachs NA, Hershey JW, et al. The p34cdc2-related cyclin-dependent kinase 11 interacts with the p47 subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 3 during apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003 Feb 14;278(7):5062–5071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206427200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Pak V, Eifler TT, Jager S, Krogan NJ, Fujinaga K, Peterlin BM. CDK11 in TREX/THOC Regulates HIV mRNA 3’ End Processing. Cell Host Microbe. 2015 Nov 11;18(5):560–570. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.10.012. •• This publication demonstrated that CDK11 is required for HIV-1 mRNA 3’ RNA processing.

- 88.Berro R, Pedati C, Kehn-Hall K, Wu W, Klase Z, Even Y, et al. CDK13, a new potential human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibitory factor regulating viral mRNA splicing. J Virol. 2008 Jul;82(14):7155–7166. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02543-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tyagi M, Pearson RJ, Karn J. Establishment of HIV latency in primary CD4+ cells is due to epigenetic transcriptional silencing and P-TEFb restriction. J Virol. 2010 Jul;84(13):6425–6437. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01519-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Beans EJ, Fournogerakis D, Gauntlett C, Heumann LV, Kramer R, Marsden MD, et al. Highly potent, synthetically accessible prostratin analogs induce latent HIV expression in vitro and ex vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jul 16;110(29):11698–11703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302634110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pandelo JD, Bartholomeeusen K, da Cunha RD, Abreu CM, Glinski J, da Costa TB, et al. Reactivation of latent HIV-1 by new semi-synthetic ingenol esters. Virology. 2014 Aug;462–463:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Spivak AM, Bosque A, Balch AH, Smyth D, Martins L, Planelles V. Ex Vivo Bioactivity and HIV-1 Latency Reversal by Ingenol Dibenzoate and Panobinostat in Resting CD4(+) T Cells from Aviremic Patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 Oct;59(10):5984–5991. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01077-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jiang G, Mendes EA, Kaiser P, Wong DP, Tang Y, Cai I, et al. Synergistic Reactivation of Latent HIV Expression by Ingenol-3-Angelate, PEP005, Targeted NF-kB Signaling in Combination with JQ1 Induced p-TEFb Activation. PLoS Pathog. 2015 Jul;11(7):e1005066. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Jamaluddin MS, Hu PW, Danels YJ, Siwak ES, Rice AP. The Broad Spectrum Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Vorinostat and Panobinostat Activate Latent HIV in CD4+ T cells in part through Phosphorylation of the T-Loop of the CDK9 Subunit of P-TEFb. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016 Jan 5; doi: 10.1089/aid.2015.0347. • This publication demonstrated that HDACis that reactivate latent HIV-1 are likely to up-regulated P-TEFb as well as modify chromatin.

- 95.Ramakrishnan R, Liu H, Rice AP. SAHA (Vorinostat) Induces CDK9 Thr-186 (T-Loop) Phosphorylation in Resting CD4 T Cells: Implications for Reactivation of Latent HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014 Mar 13; doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Mbonye U, Karn J. Transcriptional control of HIV latency: cellular signaling pathways, epigenetics, happenstance and the hope for a cure. Virology. 2014 Apr;454–455:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.02.008. • This publication is an outstanding review on mechanisms of HIV-1 latency and reactivation.

- 97.Taube R, Peterlin M. Lost in transcription: molecular mechanisms that control HIV latency. Viruses. 2013 Mar;5(3):902–927. doi: 10.3390/v5030902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]