Abstract

One of the most significant risk factors for prostate cancer (PC) is a family history of the disease, with germ-line mutations in the breast cancer predisposition gene (BRCA) 2 conferring the highest risk. We here report a 56-year-old man presented with painful gait disturbance and diagnosed PC with multiple disseminated bone metastases. The patient had a strong family history of breast cancer with his 2 nieces affected. Furthermore, his aunts and uncles from both sides were diagnosed with stomach, ovarian, and colorectal cancers. His genomic sequencing analysis of the BRCA genes revealed the same BRCA2 deleterious mutation that his breast cancer-affected nieces carried. Previous studies have suggested that BRCA2-mutated PC is associated with a more aggressive phenotype and poor prognosis. Our experience in the present case also indicated the urgent needs for novel treatment modality and PC screening in this high-risk group of patients.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, BRCA, Genetic Mutation, Family History

INTRODUCTION

One of the most significant risk factors for prostate cancer (PC) is a family history of the disease. To date, germ-line mutations in the breast cancer predisposition gene (BRCA) 2 are the genetic events that have been shown to confer the highest risk of PC at 8.6-fold in men ≤ 65 years of age (1). Although it remains unclear how BRCA2 affect prostate tumorigenesis, deleterious mutations in BRCA2 genes have been associated with a more aggressive disease and poor clinical outcomes. Furthermore, the increasing incidence of PC worldwide emphasizes the urgent need for new methods of outcome prediction and patient stratification, particularly to identify those with potentially lethal forms of the disease. We herein present a case of BRCA2-mutated PC with a family history of breast cancer. In addition, we reviewed the literature on germ-line mutations of the BRCA genes and their predictive values of patient outcomes.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 56-year-old patient presented with gait disturbance due to pain in the right leg in September 2015. His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was 3,566 ng/mL, and he was diagnosed with PC with multiple disseminated bone metastases in the whole axial and proximal appendicular skeleton (Fig. 1). The Gleason score on diagnosis was 9 (4 + 5) (Fig. 2). The digital rectal examination revealed a hard tender prostate estimated to weigh 40 g with left-sided extraprostatic extension but no rectal invasion. He was treated with hormonal therapy, including 50 mg nonsteroidal antiandrogen therapy once daily combined with an 11.25 mg injection of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist. After 2 months of therapy, his bone pain subsided, and his PSA level decreased to 740 ng/mL. His family pedigree revealed a strong history of breast cancer with his 2 nieces being diagnosed at the age of 36 and 39 years (Fig. 2). Furthermore, he had 2 aunts and 2 uncles from both sides who had been diagnosed with stomach cancer, ovarian cancer, or colorectal cancer. His genomic sequencing analysis of the BRCA genes revealed the same BRCA2 NM_000059.3:c.3744_3747delTGAG (p.Ser1248Argfs*10) mutation that his breast cancer-affected nieces carried (Fig. 3). Further PC surveillance, including digital rectal examination and PSA screening, was planned for the patient's male relatives.

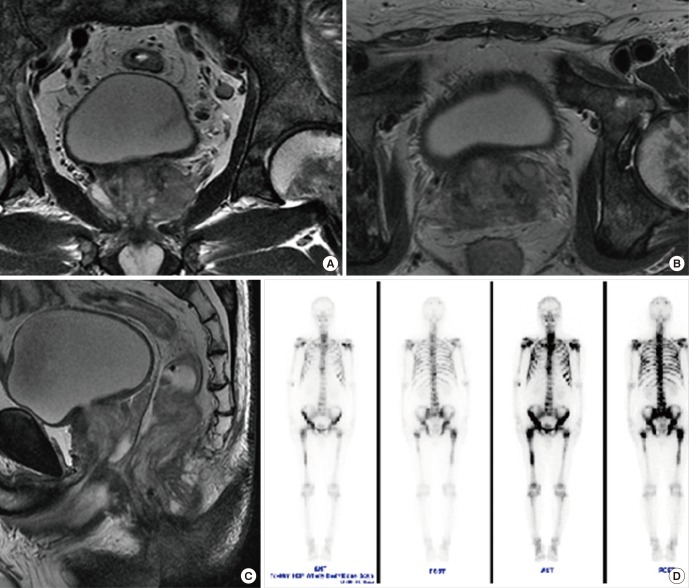

Fig. 1.

Preoperative prostate MRI and bone scan images.

(A) Sagittal view; (B) horizontal view; (C) axial view of MRI of the prostate showing left side-dominant PC with extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and enlarged left external and internal iliac lymph nodes; and (D) Disseminated bone metastasis in the whole axial and proximal appendicular bones.

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, PC = prostate cancer.

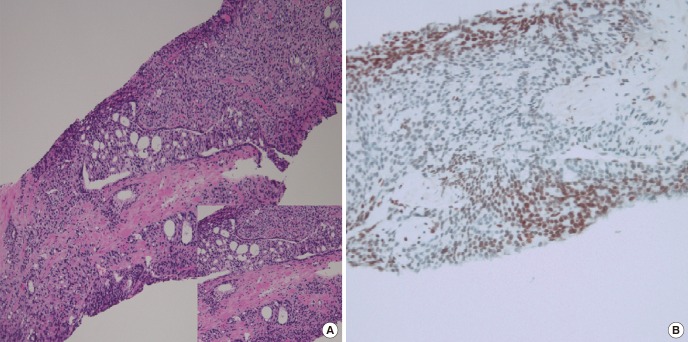

Fig. 2.

Representative microphotographs of the prostate tumor.

(A) Characteristic features of Gleason patterns 4 and 5, including fused glands and an almost complete loss of glandular lumina (H & E staining, [× 100]). (B) Immunohistochemical staining of BRCA2 (× 200).

BRCA2 = breast cancer predisposition gene 2, H & E = hematoxylin and eosin.

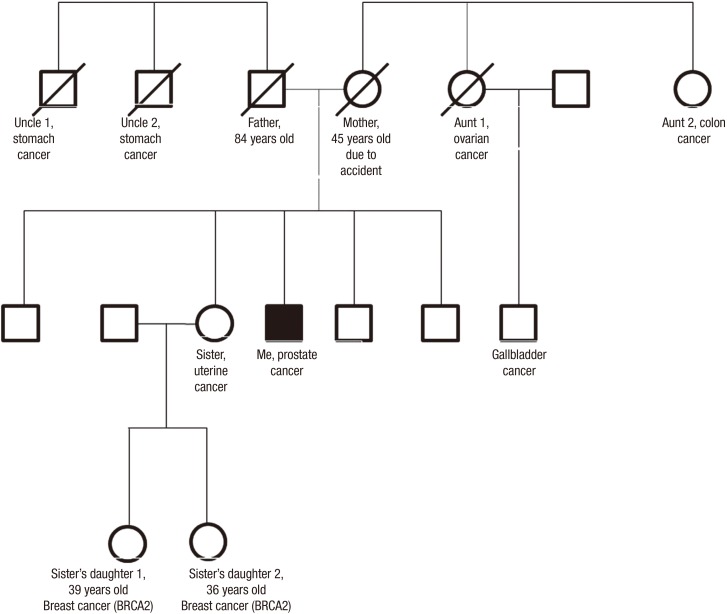

Fig. 3.

Pedigree.

The patient's mother died from a car accident at 45 years of age. His first aunt died from ovarian cancer, and her son from biliary cancer. His second aunt died from colorectal cancer. The 2 daughters of his elder sister were diagnosed with breast cancer at 39 and 36 years of age, and their gene sequencing analyses revealed that both had BRCA2 mutation NM_000059.3:c.3744_3747delTGAG (p.Ser1248Argfs*10).

BRCA2 = breast cancer predisposition gene 2.

Ethics statement

Informed written consent was submitted by the patient and the review was exempted by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center.(August 25, 2015)

DISCUSSION

The role of BRCA germ-line mutations in male cancer has been extensively studied although they are present in only 1%–2% of sporadic PC cases (1). Previous studies have estimated the relative risk for developing PC in men from the families with a pathogenic BRCA2 mutation to be 2.9–4.8 with an approximate 20% lifetime risk and a relative risk as high as 7.3 in some subgroups such as those < 65 years old (1).

BRCA2 is a tumor suppressor gene inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with incomplete penetrance (2). Its function seems to be limited to DNA recombination and repair processes, whereas a loss of function is associated with deficiency in repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Such a genomic instability might be the underlying cause of cancer predisposition resulted from deleterious mutations in the BRCA genes. Although the precise biology of BRCA2-associated aggressive PC phenotype remains to be determined, it has been suggested that in PC cells, BRCA2 downregulation by small interfering RNAs might promote cancer cell migration and invasion, possibly via the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (3).

In addition to a more aggressive tumor phenotype and more advanced tumor stage (T3–4), prostate tumors from BRCA2 mutation carriers are usually more poorly differentiated. These patients often have a shorter median cancer-specific and overall survival than non-carriers receiving similar local treatment with curative intent (4). However, even the non-carriers have a poorer outcome than others with sporadic PC, suggesting that a family history of breast cancer might also affect the prognosis of PC patients. These findings strongly support the contribution of other undetermined genetic factors to PC etiology and prognosis in breast cancer-prone families (5,6), and suggest that the family members who do not carry the deleterious BRCA family-specific mutation might inherit other underlying genetic instabilities that increase their risk of cancer. A recent study by Dite et al. (7) indicated that first-degree relatives of women diagnosed with breast cancer at a young age (≤ 35 years) had an increased risk of developing a variety of cancers, irrespective of mutation status, and that some other underlying familial factors in these families, such as variants in other genes, might predispose individuals to cancer.

Currently, there is no consensus on the most appropriate treatment for localized PC in BRCA mutation carriers, and more clinical evidence is still needed. Nonetheless, radical treatment with either surgery or radiotherapy is preferable to active surveillance, even for low-risk cases. Previous studies have also supported adjuvant treatment in BRCA mutation carriers as they often experience early nodal spread and more frequent metastasis (4). One of the most important clinical issues in the treatment of BRCA-related tumors is the choice of chemotherapy in both adjuvant and palliative settings. Platinum, taxanes, and more recently, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have been demonstrated to be active in breast and ovarian tumors harboring germ-line mutations of the BRCA genes, although its roles in PC would need further investigation (4,8,9). However, in clinical practice, it is questionable whether screening for BRCA mutations is necessary because their prevalence is low, and BRCA-positive PC patients with metastatic disease have been reported to respond to the standard chemotherapy regimen of docetaxel plus prednisolone similarly to those with wild-type BRCA (10). Additional considerations for deciding whether to undergo further treatment for metastatic PC include health insurance coverage; it is uncertain if a PARP inhibitor for treatment of PC would be covered by insurance plans because the role of PARP inhibitors in PC has not yet been clarified.

While PC screening in men might be controversial (4), these findings suggested that genetically targeted testing of pre-symptomatic men with a higher risk of aggressive and fatal PC like those from families with BRCA2 mutation carriers might be clinically justified (5,6,7). Early diagnosis might be crucial in these patients, and a careful discussion about PC screening with an experienced urologist should be encouraged to inform both BRCA2 mutation carriers and non-carriers alike that due to their underlying genetic changes, they might be at an increased risk of developing clinically significant PC that could be difficult to manage and have a poor clinical outcome.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the Korean National Cancer Center Grants (No. 1510170).

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Conceptualization: Kim SH, Joung JY, Lee KH. Data curation: Song WH, Kim SH, Park WS. Investigation: Song WH, Kim SH, Park WS. Writing - review & editing: Joung JY, Park WS, Seo HK, Chung J, Lee KH.

References

- 1.Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1310–1316. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.15.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venkitaraman AR. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cell. 2002;108:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moro L, Arbini AA, Marra E, Greco M. Mitochondrial DNA depletion reduces PARP-1 levels and promotes progression of the neoplastic phenotype in prostate carcinoma. Cell Oncol. 2008;30:307–322. doi: 10.3233/CLO-2008-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castro E, Eeles R. The role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:409–414. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Al Olama AA, Giles GG, Guy M, Severi G, Muir K, Hopper JL, Henderson BE, Haiman CA, et al. Identification of seven new prostate cancer susceptibility loci through a genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/ng.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witte JS. Prostate cancer genomics: towards a new understanding. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:77–82. doi: 10.1038/nrg2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dite GS, Whittemore AS, Knight JA, John EM, Milne RL, Andrulis IL, Southey MC, McCredie MR, Giles GG, Miron A, et al. Increased cancer risks for relatives of very early-onset breast cancer cases with and without BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1103–1108. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Audeh MW, Carmichael J, Penson RT, Friedlander M, Powell B, Bell-McGuinn KM, Scott C, Weitzel JN, Oaknin A, Loman N, et al. Oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:245–251. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, Friedlander M, Arun B, Loman N, Schmutzler RK, et al. Oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235–244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallagher DJ, Cronin AM, Milowsky MI, Morris MJ, Bhatia J, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, Offit K, Robson ME. Germline BRCA mutation does not prevent response to taxane-based therapy for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;109:713–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]