Abstract

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) demand has been rising because of its various applications. High salinity stress is a major environmental factor that interferes with normal plant growth and limits crop productivity. As well as genetic engineering to enhance stress tolerance, the use of small molecules is considered as an alternative methodology to modify plants with desired traits. The effectiveness of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors for increasing tolerance to salinity stress has recently been reported. Here we use the HDAC inhibitor, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), to enhance tolerance to high salinity in cassava. Immunoblotting analysis reveals that SAHA treatment induces strong hyper-acetylation of histones H3 and H4 in roots, suggesting that SAHA functions as the HDAC inhibitor in cassava. Consistent with increased tolerance to salt stress under SAHA treatment, reduced Na+ content and increased K+/Na+ ratio were detected in SAHA-treated plants. Transcriptome analysis to discover mechanisms underlying salinity stress tolerance mediated through SAHA treatment reveals that SAHA enhances the expression of 421 genes in roots under normal condition, and 745 genes at 2 h and 268 genes at 24 h under both SAHA and NaCl treatment. The mRNA expression of genes, involved in phytohormone [abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), ethylene, and gibberellin] biosynthesis pathways, is up-regulated after high salinity treatment in SAHA-pretreated roots. Among them, an allene oxide cyclase (MeAOC4) involved in a crucial step of JA biosynthesis is strongly up-regulated by SAHA treatment under salinity stress conditions, implying that JA pathway might contribute to increasing salinity tolerance by SAHA treatment. Our results suggest that epigenetic manipulation might enhance tolerance to high salinity stress in cassava.

Keywords: cassava, high salinity stress, epigenetics, histone modification, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA)

Introduction

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) originated in South America and is an important root crop, of which worldwide cultivation has progressed throughout tropical and subtropical regions (Olsen and Schaal, 1999). This perennial crop grows a starchy root, with starch making up 70–90% of the total dry weight (El-Sharkawy, 2004; Nuwamanya et al., 2008). Over 500 million people use cassava root starch as a source of carbohydrates (FAO, 1998; El-Sharkawy, 2004). Moreover, cassava has multiple applications including as animal feed and as a raw material for biofuel production, which contributes to building a sustainable ecosystem (Fu et al., 2016).

Soil salinity is one of the leading factors that hinder crop production globally, and development of cassava plants that are more tolerant to salinity stress is required (Carretero et al., 2008). It is well known that soil salinity affects plant cells in two ways: water deficit caused by high concentrations of salt in soil leading to decreasing water uptake by roots (osmotic stress); and high accumulation of salt in the plant, which alters Na+/K+ ratios as well as leading to excessive Na+ and Cl− content (ion cytotoxicity; Munns and Tester, 2008; Julkowska and Testerink, 2015). Previous studies have revealed that several mechanisms such as maintenance of ion homeostasis, accumulation of compatible solutes, hormonal control, antioxidant systems, and Ca2+ signaling are essential for plants to survive under high salinity stress (Jia et al., 2015). Based on those findings, genetic engineering and conventional breeding have been widely used to develop salt-tolerant plants. To improve salt tolerance of transgenic plants, genes involved in several pathways against salt stress have been used as targets for expression modification. These include transporters for ion homeostasis such as NHX1 (Apse et al., 1999), SOS1/2/3 (Shi et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2009), and HKT1 (Mølle et al., 2009); and for the accumulation of osmolytes such as proline (Kishor et al., 1995) and glycine betaine (Sakamoto and Murata, 1998); late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins (Xu et al., 1996); and enzymes for antioxidant synthesis such as GST/GPX (Roxas et al., 1997) and SOD (McKersie et al., 1999).

In addition to osmolytes, treatment with small molecules such as plant hormones has been used to enhance salt tolerance in plants. It is reported that the use of salicylic acid (SA) increases tolerance to drought and salt stress in wheat (Shakirova et al., 2003). In Arabidopsis, β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) functions as priming effect on abscisic acid (ABA) responses for drought and salinity stress, resulted in increasing these stress tolerance (Jakab et al., 2005). These results show that application of small molecules allows the improvement of plant traits responsible for stress tolerance, particularly for crops in which it is difficult to introduce traits by transformation or crossing. Furthermore, constitutive expression of stress responsive genes often induces growth inhibition. Treatment with small molecules during the optimized period may have the advantage of minimizing the growth inhibition, because stopping small-molecules application can release from the growth inhibition.

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors are effective small molecules against environmental stresses. HDAC controls the level of histone acetylation with histone acetyltransferase (HAT; Seto and Yoshida, 2014; Verdin and Ott, 2015). Histone acetylation is one of the histone modifications involved in epigenetic regulation, and recent evidence has increasingly revealed that the balance of histone acetylation plays a pivotal role in response to salinity stress (Kim et al., 2015). For example, the transcriptional co-activator ADA2b is a component of several multiprotein HAT complexes that contain GCN5 as their catalytic subunit. The mutant ada2b shows hypersensitivity to salt. This result suggests that ADA2b is involved in the regulation of histone acetylation levels for salt-induced genes through the modulation of HAT activity (Kaldis et al., 2010). Conversely, the loss of an HDAC, HDA9, resulted in reduced sensitivity to salt and drought stresses in Arabidopsis (Zheng et al., 2016). These studies imply that modulation of induced histone acetylation is inextricably linked to salinity stress response, although other histone modifications such as methylation are also known to be involved (Shen et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2015; Asensi-Fabado et al., 2016). Interestingly, the HDAC inhibitor, Ky-2, can increase gene expression for an ion transporter (SOS1) and an enzyme involved in osmolyte accumulation (P5CS), leading to increased tolerance to salt stress (Sako et al., 2016). Therefore, there is the possibility that HDAC inhibitors could be used to manipulate crops and obtain desired characteristics.

In this study, we attempt to enhance tolerance to high salinity in cassava using the commercially available HDAC inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA, vorinostat; Dokmanovic et al., 2007). The survival rate shows that SAHA helps cassava become less sensitive to high salinity stress. Immunoblotting analysis reveals that SAHA induces hyperacetylation of histones H3 and H4 in roots. Transcriptome analysis using a microarray revealed that mRNA expression of genes, involved in phytohormone ABA and jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis pathways, is strongly induced under high salinity stress condition. In addition to above two phytophormone pathways, SAHA treatment is likely to enhance ethylene and gibberellin biosynthesis pathways. Among them, an allene oxide cyclase (MeAOC4) catalyzing a crucial step in JA biosynthesis is strongly up-regulated. We discuss which pathway plays a pivotal role in inducing tolerance to salinity stress by SAHA treatment in cassava. Taken together, our results provide fundamental information on the high salinity stress response and suggest the possibility that the epigenetic manipulation via HDAC inhibition might be applicable for increasing tolerance to high salinity stress in cassava.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Cassava cultivar TMS60444 was asexually propagated in a plastic pot with Murashige and Skoog (MS) media (pH5.8, KOH) containing 4.4 g L−1 MS salts (Murashige and Skoog, 1962), 20 g L−1 sucrose, 2 μM CuSO4, and 3 g L−1 Gelrite (Wako) under a light intensity of 40–80 μmol photons m−2s−1 with a 12 h/12 h photoperiod at 28 ± 1°C. The 5-cm length shoot tops of 3-month-old cassava plantlets were cut and then transferred to liquid MS media without agar. After 1 week incubation, the plantlets showing root elongation were subjected to each analysis as follows.

Effect of SAHA treatment on survival rate and biomass under salinity stress condition

To reveal to which extent SAHA treatment alleviates cassava plants from salinity stress, survival rate and biomass (fresh and dry weight) were measured as follows. At 1 week-incubation after the transfer of cut plantlets to liquid medium, the plantlets were incubated on liquid MS media supplemented with 100 μM SAHA (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid: N-hydroxy-N′-phenyloctanediamide: vorinostat, from Tokyo Chemical Industry, code-H1388) for 24 h. SAHA was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and DMSO treatment served as the control for all analyses. Then, the plantlets were transferred to 200 mM NaCl containing liquid MS media for 10 days and subsequently transferred to normal liquid MS medium for 1 month to observe phenotype and count survival rate in each condition. At least 13 cassava plantlets were used for each condition. The survival rate was based on the percentage of surviving plants. Plants with regenerated leaves and green stems were counted as surviving plants, while the plants with white stems having no new leaves were counted as dead ones. The fresh weight (FW) of root and shoot samples was measured immediately after harvesting. To measure the dry weight (DW), cassava samples were incubated at 60°C for 1 week. FW and DW were measured from the regenerated plants that had 3 or more leaves. Three biological replicates were conducted for all analyses.

Measurement of Na+ and K+ contents

The cassava samples were washed for 5 s three times using distilled water. Stems and leaves were cut separately using mineral-free carbon knives (Feather 5) and kept at −80°C until use. Analytical measurement of 23Na and 39K content was conducted using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS; NexION300, Perkin Elmer). Firstly, the cassava samples were dried using a freeze dryer for 3 days. The cassava sample weight was measured. Then 5 mL of conc. HNO3 was added to the cassava samples. The cassava samples were incubated with concentrated HNO3 overnight. After that, the cassava samples were digested using a microwave sample preparation system (MultiWave-3000, Perkin Elmer). All samples were completely digested prior to running on the ICP-MS. The digested samples were adjusted to a volume of 50 mL with Milli-Q water, then filtered through 5B filter paper (Advantec). The ICP-MS analysis was carried out as described previously (Itouga et al., 2014). Three independent biological replicates were generated for each condition. Na+ and K+ content were analyzed statistically with a t-test.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting analysis

The leaf and root samples were ground using a Multi-beads shocker (Yasui Kikai) and 200 μL of 2 × Laemmli sample buffer [2% SDS, 50.4% (w/v) glycerol, 0.02 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) with 2% 2-mercaptoethenol] was immediately added to the powder. The mixture was heated at 95°C for 3 min then placed on ice for 5 min, and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 14,000 × g. The protein supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis. After gel electrophoresis, the protein was blotted on equilibrated Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Millipore). Then the blotted membrane was blocked using 5% skim milk at room temperature for 1 h. Next, the membrane was incubated at 4°C overnight for the primary antigen–antibody interaction. Secondary antibodies were incubated with the membrane for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, detection was carried out using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE). Primary antibodies were H3 (Abcam, 1791), H4 (Abcam, 10158), acH3 (Merck Millipore, 06-599), and acH4 (Merck Millipore, 06-866), diluted 1:5000, 1:3000, 1:2000, and 1:5000, respectively. The secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit IgG (GE, NA931), diluted 1:25,000.

RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted using Plant RNA Isolation Reagent (Invitrogen) following spin-column RNA precipitation using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Briefly, the sample tissues were ground into fine powder using a Multi-beads shocker. The tissue powder was used for RNA extraction using Plant RNA Isolation Reagent according to the manufacturer's instruction (Invitrogen). To clean the RNA solution, after adding 20 μL of RNase-free water to the RNA pellet, the RNA solution was purified using spin-column RNA precipitation followed by addition of RNase-Free DNase (Qiagen). In order to remove contaminated DNA completely, the process for RNA purification using spin-column RNA precipitation with DNase treatment was repeated twice. All samples were stored at −80°C until use.

Microarray analysis

For microarray analysis, the plantlets were treated with 100 μM SAHA for 24 h, followed by treatment with 200 mM NaCl for 2 or 24 h. The quality of total RNA was evaluated using a Bioanalyzer system (Agilent). Microarray analysis was performed according to the procedure of Utsumi et al. (2012). Briefly, total RNA was labeled with cyanin-3 (Cy3) using the Quick Amp Labeling kit (Agilent Technologies). Next, the Cy3-labeled cRNA was fragmented and hybridized to the Agilent microarray (GPL14139; Utsumi et al., 2016). After hybridization, the microarrays were washed and immediately scanned on an Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner (G2505B) using one color scan setting for 8 × 60 K array slides. Feature Extraction software (Ver. 9.1, Agilent Technologies) was used to process the digital images. Three independent experiments were performed for each condition. After normalization, microarray probes were detected based on one-way ANOVA with Benjamini–Hochberg correction (FDR) < 0.0001. An AGI gene code is shown in Tables 1–6, if the protein encoded in each gene (probe ID) has the sequence similarity with those in Arabidopsis at E ≤ 1 × 10−5. The E-value for each probe ID is available in Tables S1–S5. Gene ontology (GO) analyses were carried out using agriGO at http://bioinfo.cau.edu.cn/agriGO/. The information from the microarray data is available on the GEO website (GEO ID: GSE84715).

Table 1.

List of top 40 cassava genes upregulated (log2 ratio > 1; FDR < 0.0001) in roots by treatment with 200 mM NaCl for 2 h in non-SAHA-pretreated plants.

| ProbeID | AGI codea | Encoded proteins/other featuresb | w/o SAHAc | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| log2 ratio (2 h NaCl/0 h NaCl) | ||||

| RknMes02_006505 | AT1G52690 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein (LEA) family protein | 10.250 | 3.36E-06 |

| RknMes02_053823 | AT2G42850 | Cytochrome P450, family 718 | 8.743 | 2.44E-07 |

| RknMes02_033569 | AT3G63060 | EID1-like 3 | 8.738 | 3.62E-05 |

| RknMes02_025528 | AT3G14440 | Nine-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 3 | 8.526 | 4.44E-05 |

| RknMes02_038832 | AT3G24310 | Myb domain protein 305 | 8.298 | 1.01E-05 |

| RknMes02_057161 | AT4G33467 | Unknown protein | 8.062 | 1.13E-05 |

| RknMes02_052347 | AT3G51810 | Stress induced protein | 6.657 | 7.15E-05 |

| RknMes02_056041 | AT3G30210 | Myb domain protein 121 | 6.620 | 1.01E-06 |

| RknMes02_051689 | AT4G35680 | Arabidopsis protein of unknown function (DUF241) | 6.399 | 1.88E-05 |

| RknMes02_039694 | AT3G03341 | Unknown protein | 6.309 | 6.19E-06 |

| RknMes02_008877 | AT4G31240 | Protein kinase C-like zinc finger protein | 5.793 | 7.87E-06 |

| RknMes02_003939 | AT5G51760 | ABA-hypersensitive germination 1 | 5.679 | 5.34E-05 |

| RknMes02_027987 | AT1G60420 | DC1 domain-containing protein | 5.659 | 6.85E-06 |

| RknMes02_056865 | AT3G61060 | Phloem protein 2-A13 | 5.645 | 2.96E-05 |

| RknMes02_055843 | AT5G59190 | Subtilase family protein | 5.563 | 2.73E-05 |

| RknMes02_054690 | AT4G11360 | RING/U-box superfamily protein | 5.531 | 4.68E-06 |

| RknMes02_026274 | AT5G40390 | Raffinose synthase family protein | 5.531 | 3.30E-06 |

| RknMes02_055373 | AT3G55646 | Unknown protein | 5.518 | 1.07E-05 |

| RknMes02_009395 | AT2G40170 | Stress induced protein | 5.427 | 9.73E-05 |

| RknMes02_056706 | AT1G11530 | C-terminal cysteine residue is changed to a serine 1 | 5.401 | 1.08E-05 |

| RknMes02_028787 | AT1G19640 | Jasmonic acid carboxyl methyltransferase | 5.366 | 3.94E-06 |

| RknMes02_017023 | AT4G16160 | ATOEP16-2, ATOEP16-S | 5.332 | 8.36E-07 |

| RknMes02_019566 | AT4G27450 | Aluminum induced protein with YGL and LRDR motifs | 5.239 | 3.25E-05 |

| RknMes02_010142 | AT5G66110 | Heavy metal transport/detoxification superfamily protein | 5.097 | 5.83E-06 |

| RknMes02_002573 | AT5G59220 | Highly ABA-induced PP2C gene 1 | 5.084 | 4.68E-05 |

| RknMes02_055268 | AT4G25410 | Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) DNA-binding superfamily protein | 5.070 | 1.15E-05 |

| RknMes02_031261 | AT4G27410 | Responsive desiccation 26 | 5.040 | 1.01E-05 |

| RknMes02_010484 | AT5G57050 | ABA insensitive 2 | 5.009 | 3.93E-05 |

| RknMes02_006418 | AT1G18100 | Mother of FT and TFL1 | 4.998 | 4.15E-06 |

| RknMes02_013801 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor15-related | 4.960 | 4.62E-05 | |

| RknMes02_034838 | AT2G29380 | Highly ABA-induced PP2C gene 3 | 4.949 | 1.08E-05 |

| RknMes02_006068 | AT1G07430 | Highly ABA-induced PP2C gene 2 | 4.937 | 7.43E-06 |

| RknMes02_038687 | AT5G42290 | Transcription activator-related | 4.840 | 8.20E-07 |

| RknMes02_051430 | AT5G23960 | Terpene synthase 21 | 4.821 | 2.45E-05 |

| RknMes02_035128 | AT1G44446 | Arabidopsis thaliana Chlorophyll A Oxygenase | 4.785 | 8.07E-05 |

| RknMes02_056689 | AT3G59850 | Pectin lyase-like superfamily protein | 4.766 | 4.17E-06 |

| RknMes02_023528 | Protein phosphate 2C 3-related | 4.718 | 2.74E-05 | |

| RknMes02_036024 | AT5G64750 | ABA repressor1 | 4.671 | 5.55E-05 |

| RknMes02_018746 | Protein phosphatase 2C | 4.638 | 6.38E-05 | |

| RknMes02_047856 | AT5G03850 | Nucleic acid-binding, OB-fold-like protein | 4.621 | 5.20E-05 |

AGI code is shown if proteins encoded in each cassava gene (probe ID) have high amino acid sequence similarity (E ≤ 10−5) to Arabidopsis homologs.

Encoded proteins/other features indicate the putative functions of the gene products that are expected from sequence similarity. The information for the NCBI protein reference sequence with the highest sequence similarity to the probes is shown.

Plants that were not pretreated with SAHA were used.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng total RNA with random primers. ReverTra Ace (TOYOBO) was used for the reverse transcription reaction according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transcript levels were assayed using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Gene-specific primers were designed using the PrimerQuest tool (http://sg.idtdna.com/primerquest/Home/Index). Melting curve analysis was conducted to validate the specificity of the PCR amplification. For qRT-PCR, three biological replicates were conducted. Actin was used as reference gene to normalize data (cassava4.1_009807m). The relevant primers are listed in Table S6. Three independent biological replicates were generated for each condition. Changes in gene expression were analyzed statistically with a t-test.

Construction of phylogenetic tree

An evolutionary tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016). The tree was evaluated with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Results

SAHA enhances salinity stress tolerance in cassava

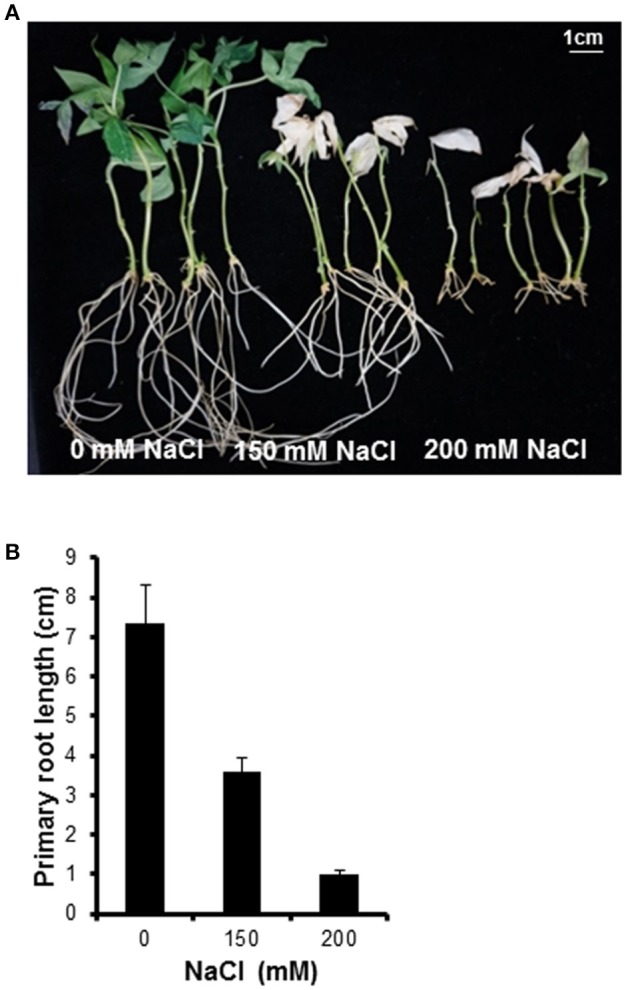

To confirm which NaCl concentration inhibits growth in cassava, plantlets were incubated in liquid medium containing different NaCl concentrations. A concentration of 200 mM NaCl clearly inhibited the growth of cassava plantlets (Figure 1A). After transfer to 200 mM NaCl salt medium for 1 week, the plantlets' older leaves started to turn yellow. At 2 weeks after transfer to salt medium, leaves showed chlorosis at both 150 and 200 mM NaCl. After 14-d incubation with 0, 150, and 200 mM NaCl, plants showed root growth of 7.4 ± 2.1, 3.6 ± 0.8, and 1 ± 0.2 cm, respectively (Figure 1B). The 200 mM NaCl concentration was selected for further experiments.

Figure 1.

Plant phenotype after treating with various NaCl concentrations. (A) Morphological observation of cassava after 14-day salt stress treatment. NaCl concentrations of 0, 150, and 200 mM were used. (B) Inhibition of primary root elongation by salinity stress. Error bars represent the means ± SD (n = 5–6).

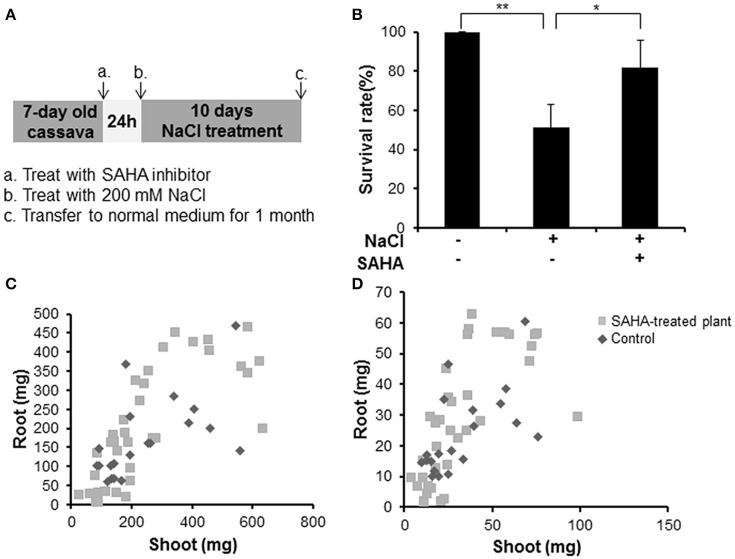

To analyze whether SAHA treatment enhances tolerance to salinity stress in cassava, we counted the survival rate of SAHA-treated plants (Figure 2A). SAHA-treated plants showed a 30.6% higher survival rate than non-treated plants under salinity stress conditions (Figure 2B). Fresh and dry weight measurement revealed that SAHA treatment increased biomass in roots (Figures 2C,D). These results suggest that SAHA treatment improves tolerance to high salinity stress in cassava.

Figure 2.

Increase in survival rate and plant weight by SAHA treatment under high salinity stress conditions in cassava. (A) Experimental condition. Cassava plantlets were treated with 100 μM SAHA for 24 h then subjected to 200 mM NaCl medium for 10 days. The survival rate was counted after transferring cassava to normal medium for 1 month. (B) Survival rate under high salinity stress of non-treated plants and SAHA-treated plants. Three independent experiments were performed (at least 13 plants per experiment). (C,D) Comparison of plant fresh weight (C) and dry weight (D) between non-treated plants and SAHA-treated plants. Asterisks indicate significantly different means (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005) as determined with a t-test. Error bars represent the mean ± SD.

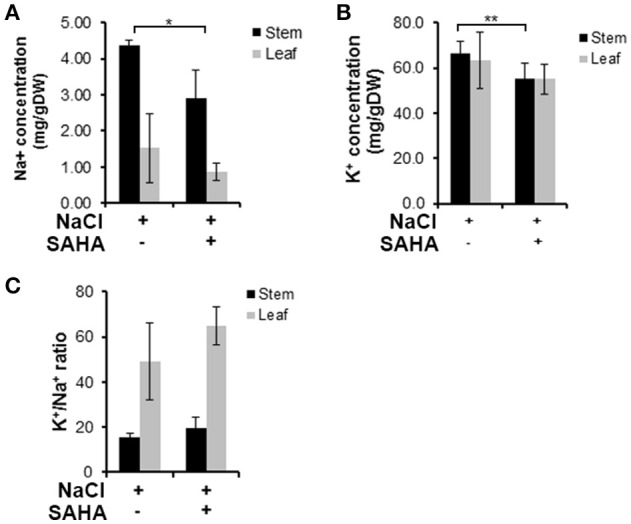

Concentration of Na+ and K+ in stems and leaves under high salinity stress

The concentration of sodium (23Na) and potassium (39K) in stem and leaf samples was quantitatively analyzed by ICP-MS to reveal the extent of SAHA treatment's influence on ion homeostasis under salinity stress conditions. SAHA-treated plants had reduced Na+ concentrations in both stems (2.9 mg g−1 DW) and leaves (0.87 mg g−1 DW) compared with those in control plants (stems and leaves: 4.36 and 1.52 mg g−1 DW, respectively; Figure 3A). However, there was no obvious difference in K+ concentrations in SAHA-treated plants and control plants, resulting in higher K+/Na+ ratios in SAHA-treated plants than in control plants (Figures 3B,C). These results suggest that SAHA treatment allows cassava to control ion homeostasis under high salinity stress conditions.

Figure 3.

Na+ and K+ content in stems and leaves under high salinity stress. (A,B) Na+ and K+ concentrations in the stems and leaves of plants exposed to 100 μM SAHA then subjected to 200 mM NaCl for 2 h. (C) the K+/Na+ ratio of stems and leaves of cassava plants. Asterisks indicate significantly different means (*p < 0.02, **p < 0.05) as determined with a t-test. Error bars represent the mean ± SD. Three independent biological replicates were performed for each condition.

Immunoblotting analysis of histones H3 and H4 acetylation

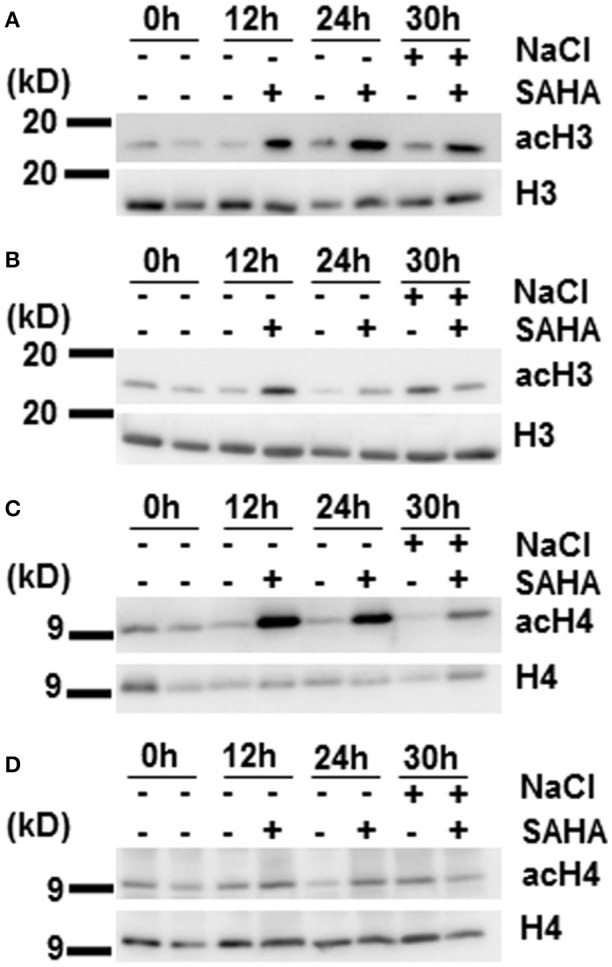

It has so far been unclear whether SAHA functions as the HDAC inhibitor in plants. We performed immunoblotting analysis to determine whether SAHA has an effect on histone acetylation levels. Cassava plantlets treated with 100 μM SAHA for 12 or 24 h, and cassava plantlets treated with 100 μM SAHA for 24 h then subjected to 200 mM NaCl for 6 h, were used for detecting histone acetylation status. Hyperacetylation of histones H3 and H4 was detected in the SAHA-treated plants compared with the control plants, especially in root samples (Figures 4A,C). Levels of histone acetylation were significantly increased at 12 and 24 h of SAHA treatment and remained higher up to 30 h after additional NaCl treatment. In contrast to roots, the acetylation level of histone H3 in leaf samples was slightly induced at 12 h and returned to a level similar to that of non-SAHA treated plants at 24 h (Figure 4B). There was no difference in acetylation levels of histone H4 in leaves between SAHA-treated plants and control plants (Figure 4D). These results suggest that SAHA mainly induces hyperacetylation of histones H3 and H4 in the roots, which may lead to transcriptional changes that enhance tolerance to high salinity stress in cassava.

Figure 4.

Changes in histones H3 and H4 acetylation levels during SAHA-treatment. Cassava plantlets were treated with 100 μM SAHA for 12 and 24 h. The 24 h SAHA treated-plants were the subjected to 200 mM NaCl for 6 h. (A,B) Detection of histone acetylation levels by western blotting (WB) with anti-AcH3 antibody in root (A) and leaf (B) samples. (C,D) The detection of histone acetylation levels by WB with anti-AcH4 antibody in root (C) and leaf (D) samples.

Transcriptome analysis in response to salinity stress

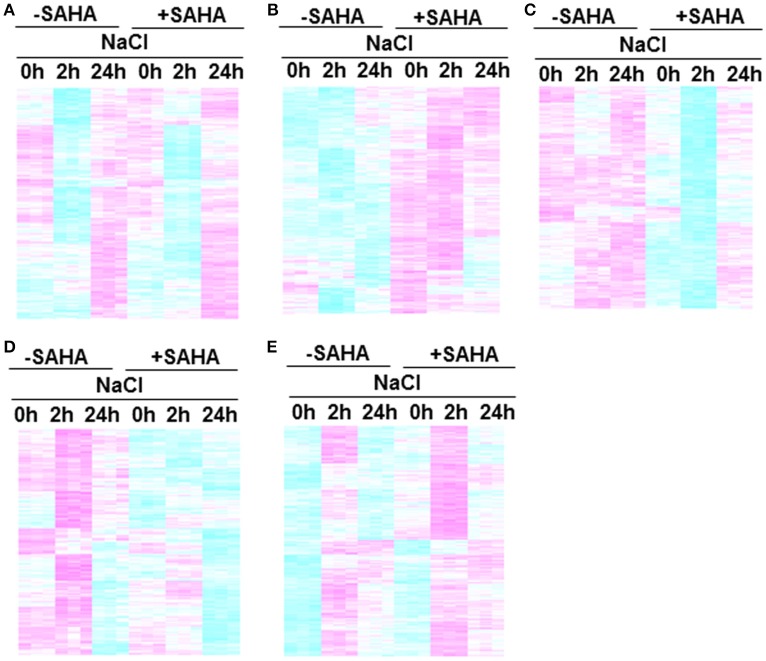

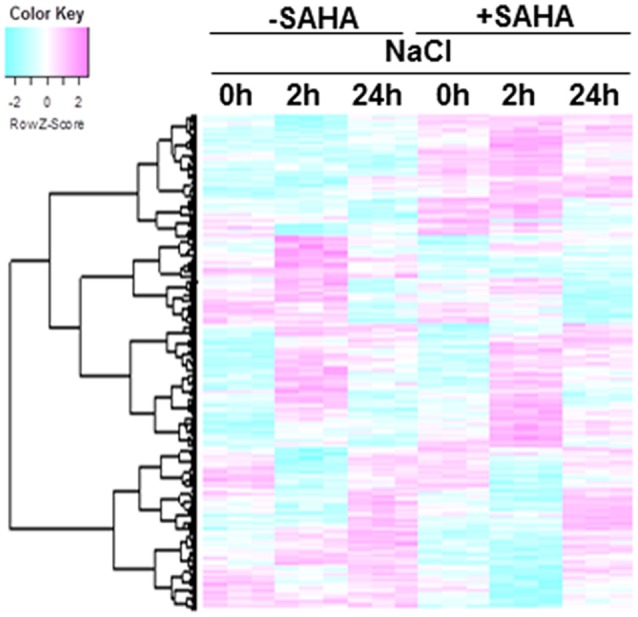

To understand responses to salt stress and unveil the mechanism underlying increased tolerance to salinity stress under SAHA treatment in cassava, the transcriptional changes in roots and leaves were analyzed. For root samples, there were 4389 genes with significant expression changes [one-way ANOVA with Benjamini–Hochberg correction (FDR) < 0.0001] in at least one condition (Figure 5). In contrast, only 53 genes showed significant differences in mRNA expression in leaves (Table S7). These data are consistent with the results of immunoblotting analysis.

Figure 5.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of salt-responsive genes and SAHA-responsive genes in cassava roots. The expression profiles of cassava genes were obtained from cassava plantlets treated with 100 μM SAHA for 24 h then subjected with 200 mM NaCl for 2 and 24 h. Transcript data was generated from 3 replicates. The heat map represents the Z-score. The key shows the Z-score region from −2 to 2. Red represents up-regulated genes while blue represents down-regulated genes. The 4389 differentially expressed genes were detected using one-way ANOVA, BH FDR < 0.0001.

The heatmap shows significant differences among treatment conditions in root samples. According to their expression profiles, genes differentially expressed in roots can be divided into five classes (Figures 6A–E). GO analysis was used to gain an overview of the functions of genes in each class. Class 1 contains SAHA-unaffected genes with functions assigned to GO:0000003 (reproduction), GO:0009791 (post-embryonic development), and GO:0008152 (metabolic process; Figure 6A). Class 2 contains genes up-regulated by SAHA treatment. GO enrichment analysis revealed that the majority of the genes in this group belong to GO:0050896 (response to stimulus), GO:0044237 (cellular metabolic process), and GO:0044238 (primary metabolic process; Figure 6B). Classes 3 and 4 contain genes down-regulated by the effect of SAHA treatment at 2 h and 24 h NaCl treatment. Salt stress-unresponsive genes and transient salt stress-responsive genes were enriched in class 3 (Figure 6C) and class 4 (Figure 6D), respectively. GO enrichment analysis indicated that GO:0051179 (localization), GO:0006810 (transport), GO:0016043 (cellular component organization), and GO:0048856 (anatomical structure development) are included in class 3, whereas GO:0051179 (localization) and GO:0006810 (transport) are included in class 4. Class 5 contains the most genes (1103 genes). Class 5 is a group of salt-responsive genes that are up-regulated at 2 h under both NaCl and SAHA treatment. Several gene ontology (GO) categories were enriched among these genes, such as GO:0006950 (response to stress), GO:0009414 (response to water deprivation), GO:0009651 (response to salt stress), GO:0009737 (response to abscisic acid stimulus), and GO:0006082 (organic acid metabolic process; Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

Clustering of genes in root transcriptome. Each cluster includes genes that responded to treatment conditions: (A) Class 1, SAHA-unaffected genes; (B) Class 2, genes up-regulated by SAHA treatment; (C) Class 3, enriched salt-stress unresponsive genes down-regulated at 2 h after NaCl addition in SAHA-pretreated plants (D) Class 4, enriched salt-stress responsive genes down-regulated at 2 h after NaCl addition in SAHA-pretreated plants, (E) Class 5, salt-responsive genes up-regulated at 2 h after NaCl addition in SAHA-pretreated plants.

Genes related to salinity stress response in cassava

As GO ontology analysis revealed, class 5 contains high salinity stress-responsive genes involved in ABA biosynthesis and signal transduction, including homologs of Arabidopsis genes NCED3 (MeNCED3: RknMes02_025528: cassava4.1_026283m, Tables 1, 2), EDL3 (MeEDL3: RknMes02_033569: cassava4.1_030886m, Tables 1, 2), ABI1 (MeABI1: RknMes02_033475: cassava4.1_020355m, Tables S1, S2), ABI2 (MeABI2: RknMes02_010484: cassava4.1_010060m, Tables 1, 2), and other PP2Cs, such as AHG1 (MeAHG1: RknMes02_003939: cassava4.1_013309m, Tables 1, 2), AHG3 (MeAHG3: RknMes02_013552: cassava4.1_008067m, Tables S1, S2), HAI1 (MeHAI1: RknMes02_002573: cassava4.1_007998m, Table 1), HAI2 (MeHAI2: RknMes02_006068: cassava4.1_007913m, Tables 1, 2), HAB1 (MeHAB1: RknMes02_048414: cassava4.1_005959m, Tables S1, S2) (Ma et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis, the salt-induced upregulation of several transcription factors including ATAF1, ATHB12, NAP, AZF2, HSF2, RD26, and ATERF4, has been reported (Ma et al., 2006; Matsui et al., 2008). In cassava, salt stress induced the expression of their homologs MeATAF1 (RknMes02_016900: cassava4.1_013132m, Tables S1, S2), MeATHB12 (RknMes02_016407: cassava4.1_015049m, Table 2), MeNAP (RknMes02_036224: cassava4.1_013467m, Tables S1, S2), and MeRD26 (RknMes02_031261: cassava4.1_010999m, Tables 1, 2). LEA proteins, whose overexpression gives tolerance to salinity stress, are regulated by ABA in land plants and thought to function as molecular shields to prevent aggregation caused by dehydration (Shinde et al., 2012). MeLEA (RknMes02_006505: cassava4.1_025947m) showed the highest the highest up-regulated gene by salt stress (Table 1, Table S1). These results suggest that ABA synthesis and its signal transduction pathway coordinate the basis of the response to salinity stress in cassava. This is consistent with previous data in Arabidopsis (Matsui et al., 2008).

Table 2.

List of top 40 cassava genes upregulated (log2 ratio > 1; FDR < 0.0001) in roots by treatment with 200 mM NaCl for 24 h in non-SAHA-pretreated plants.

| ProbeID | AGI codea | Encoded proteins/other featuresb | w/o SAHAc | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| log2 ratio (24 h NaCl/0 h NaCl) | ||||

| RknMes02_038832 | AT3G24310 | Myb domain protein 305 | 6.437 | 1.01E-05 |

| RknMes02_006505 | AT1G52690 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein (LEA) family protein | 5.890 | 3.36E-06 |

| RknMes02_033569 | AT3G63060 | EID1-like 3 | 5.813 | 3.62E-05 |

| RknMes02_057161 | AT4G33467 | Unknown protein | 5.701 | 1.13E-05 |

| RknMes02_049529 | AT3G54420 | Chitinase class IV | 5.653 | 4.12E-05 |

| RknMes02_010887 | AT2G43590 | Chitinase family protein | 5.245 | 6.27E-05 |

| RknMes02_008877 | AT4G31240 | Protein kinase C-like zinc finger protein | 5.162 | 7.87E-06 |

| RknMes02_027987 | AT1G60420 | DC1 domain-containing protein | 5.143 | 6.85E-06 |

| RknMes02_017023 | AT4G16160 | ATOEP16-2, ATOEP16-S | 5.118 | 8.36E-07 |

| RknMes02_003939 | AT5G51760 | ABA-hypersensitive germination 1 | 4.407 | 5.34E-05 |

| RknMes02_052347 | AT3G51810 | Stress induced protein | 4.200 | 7.15E-05 |

| RknMes02_010484 | AT5G57050 | ABA insensitive 2 | 4.153 | 3.93E-05 |

| RknMes02_039460 | AT5G59220 | Highly ABA-induced PP2C gene 1 | 3.978 | 4.47E-05 |

| RknMes02_056041 | AT3G30210 | Myb domain protein 121 | 3.893 | 1.01E-06 |

| RknMes02_018746 | Protein phosphatase 2C | 3.850 | 6.38E-05 | |

| RknMes02_055947 | AT1G16770 | Unknown protein | 3.846 | 1.54E-06 |

| RknMes02_025528 | AT3G14440 | Nine-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 3 | 3.832 | 4.44E-05 |

| RknMes02_047856 | AT5G03850 | Nucleic acid-binding, OB-fold-like protein | 3.734 | 5.20E-05 |

| RknMes02_051689 | AT4G35680 | Arabidopsis protein of unknown function (DUF241) | 3.571 | 1.88E-05 |

| RknMes02_006068 | AT1G07430 | Highly ABA-induced PP2C gene 2 | 3.526 | 7.43E-06 |

| RknMes02_023528 | Protein phosphatase 2C 3-related | 3.493 | 2.74E-05 | |

| RknMes02_034838 | AT2G29380 | Highly ABA-induced PP2C gene 3 | 3.479 | 1.08E-05 |

| RknMes02_016407 | AT3G61890 | Homeobox 12/homeobox 7 | 3.312 | 1.38E-05 |

| RknMes02_039694 | AT3G03341 | Unknown protein | 3.288 | 6.19E-06 |

| RknMes02_013832 | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein ATHB-12-related | 3.211 | 1.30E-05 | |

| RknMes02_035128 | AT1G44446 | Arabidopsis thaliana Chrolophyll A oxygenase | 3.193 | 8.07E-05 |

| RknMes02_053159 | AT4G16835 | Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-like superfamily protein | 3.142 | 8.93E-06 |

| RknMes02_054176 | AT5G20230 | Blue-copper-binding protein | 3.117 | 1.93E-05 |

| RknMes02_048392 | AT2G38940 | Phosphate transporter 1;4 | 2.986 | 5.87E-06 |

| RknMes02_010463 | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein ATHB-12-related | 2.957 | 1.26E-05 | |

| RknMes02_031261 | AT4G27410 | Responsive to desiccation 26 | 2.952 | 1.01E-05 |

| RknMes02_056689 | AT3G59850 | Pectin lyase-like superfamily protein | 2.922 | 4.17E-06 |

| RknMes02_058983 | AT1G24530 | Transducin/WD40 repeat-like superfamily protein | 2.901 | 1.15E-05 |

| RknMes02_054233 | AT5G42200 | RING/U-box superfamily protein | 2.829 | 4.97E-06 |

| RknMes02_006418 | AT1G18100 | PEBP (phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein) family protein | 2.819 | 4.15E-06 |

| RknMes02_010142 | AT5G66110 | Heavy metal transport/detoxification superfamily protein | 2.742 | 5.83E-06 |

| RknMes02_054543 | AT1G60190 | ARM repeat superfamily protein | 2.669 | 3.46E-05 |

| RknMes02_046170 | AT2G43870 | Pectin lyase-like superfamily protein | 2.653 | 1.88E-05 |

| RknMes02_009426 | AT5G14860 | UDP-Glycosyltransferase superfamily protein | 2.641 | 5.69E-05 |

| RknMes02_025204 | AT1G09960 | Sucrose transporter 4 | 2.611 | 9.43E-05 |

AGI code is shown if proteins encoded in each cassava gene (probe ID) have high amino acid sequence similarity (E ≤ 10−5) to Arabidopsis homologs.

Encoded proteins/other features indicate the putative functions of the gene products that are expected from sequence similarity. The information for the NCBI protein reference sequence with the highest sequence similarity to the probes is shown.

Plants that were not pretreated with SAHA were used.

In addition to ABA, the hormones JA and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) are also involved in salt stress response. Consistent with previous reports that MeJA induces salt responsive genes in roots (Ma et al., 2006), our transcriptome analysis from root sample detected the induced mRNA expression of genes for JA/MeJA biosynthesis (MeACX2: RknMes02_027394: cassava4.1_002855m, Table S1; MeACX3: RknMes02_012214: cassava4.1_002966m, Table S1; and MeJMT: RknMes02_028787, cassava4.1_010155m, Table 1), suggesting that the JA signaling pathway is also involved in response to salt stress in cassava.

The expression levels of osmoprotectant biosynthesis-related genes, such as Δ-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (P5CS) and raffinose synthase were induced under salinity stress condition. P5CS1 (MeP5CS1: RknMes02_003952: cassava4.1_002374m) catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of proline. MeP5CS1 was up-regulated at 2 and 24 h NaCl treatment (Tables S1, S2). Soluble sugars of the raffinose family have been associated with plant response to abiotic stresses. Raffinose synthase (RS) is responsible for raffinose biosynthesis. It has been reported that high salinity stress increased RS5 transcription (Egert et al., 2013; ElSayed et al., 2014). The expression of MeRS5 (RknMes02_026274: cassava4.1_002019m) was upregulated at 2 h NaCl treatment (Table S1). Proline and raffinose are likely to be synthesized and function as osmoprotectants under salinity stress in cassava.

SAHA pretreatment-upregulated genes identified by transcriptome analysis

We identified 421 genes whose expression was upregulated by 24 h SAHA treatment (Table S3). After pre-treatment of SAHA, 745 and 268 genes were upregulated by 2 and 24 h salt treatment, respectively (Tables S4, S5).

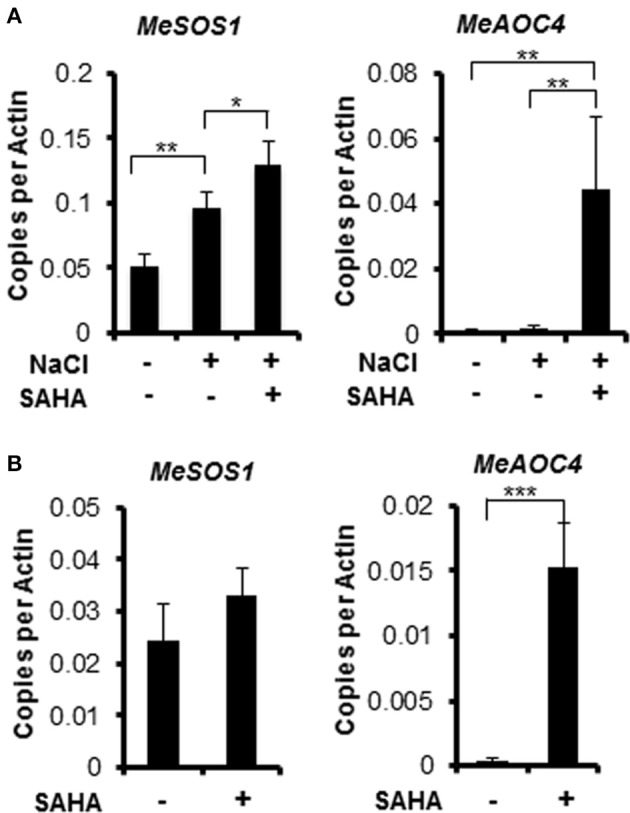

Salt Overly Sensitive1 (SOS1) is a gene responsible for increased salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis plants treated with the HDAC inhibitor Ky-2. The HDAC inhibitor strongly induced the expression of AtSOS1 to 5-, 3.5-, and 1.67-fold during NaCl treatment for 0, 2 and 10 h, respectively (Sako et al., 2016). Overexpression of SOS1 enhances tolerance to salinity stress in Arabidopsis (Shi et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2009) and tobacco (Yue et al., 2012). SAHA treatment enhanced MeSOS1 gene expression to 1.35-fold compared with untreated plants (Figure 7A). Although, the upregulation of MeSOS1 gene by SAHA treatment was not so significant (Figure 7B), the slight enhanced expression of MeSOS1 might contribute to the increased salinity stress tolerance by SAHA pretreatment in cassava.

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of MeSOS1 (Salt Overly Sensitive 1) and MeAOC4 (Allene Oxide Cyclase 4) genes using quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. (A) Cassava plantlets were treated with 100 μM SAHA for 24 h then subjected to 200 mM salt medium for 2 h. (B) Cassava plantlets were treated with 100 μM SAHA for 24 h. Root samples were collected. Asterisks indicate significantly different means (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001) as determined with a t-test. Actin was used as reference gene. Error bars represent the means ± SD. Three independent biological replicates were performed for each condition.

Transcriptome analysis revealed that the mRNA expression of genes, involved in phytohormone [abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), ethylene, and gibberellin] biosynthesis pathways, was up-regulated after NaCl treatment in SAHA-pretreated roots (Table S8). Among them, the expression of an allene oxide cyclase gene (MeAOC4: RknMes02_051874: cassava4.1_022180m) was strongly induced by SAHA treatment (Tables 3–5). SAHA treatment enhanced MeAOC4 expression to 32.8-fold compared with untreated plants (Figure 7A). Previous studies have revealed that overexpression of AOCs can confer salinity stress tolerance to several crops (Yamada et al., 2002; Pi et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2014). According to the current cassava genome database, AOCs constitute a small gene family (MeAOC3-1: RknMes02_049533: cassava4.1_014582m; MeAOC3-2: RknMes02_054684: cassava4.1_026961m; and MeAOC4: RknMes02_051874: cassava4.1_022180m) in cassava (Figure S1). Our transcriptome analysis revealed that MeAOC3-2 is a high salinity stress-responsive gene and the expression of MeAOC4 is not upregulated by high-salinity stress (Figure S1). SAHA treatment increased the expression of MeAOC4 to 35-fold (Figure 7B), suggesting that activation of the JA pathway mediated by overexpression of MeAOC4 might play a pivotal role in alleviating high-salinity stress in cassava.

Table 3.

List of top 40 cassava genes upregulated (log2 ratio > 1; FDR < 0.0001) in roots by SAHA treatment.

| ProbeID | AGI codea | Encoded proteins/other featuresb | log2 ratio (SAHA 24 h/non-treated) | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RknMes02_051874 | AT1G13280 | Allene oxide cyclase 4 | 5.135 | 1.70E-07 |

| RknMes02_058141 | AT3G06720 | Importin alpha isoform 1 | 4.941 | 1.01E-06 |

| RknMes02_055141 | AT2G40210 | AGAMOUS-like 48 | 4.914 | 1.18E-06 |

| RknMes02_048392 | AT2G38940 | Phosphate transporter 1;4 | 4.837 | 5.87E-06 |

| RknMes02_058688 | AT3G28880 | Ankyrin repeat family protein | 4.808 | 4.22E-07 |

| RknMes02_055845 | AT3G51880 | High mobility group B2///high mobility group B1 | 4.757 | 1.37E-05 |

| RknMes02_058115 | AT3G07390 | Auxin-induced in root cultures 12 | 4.728 | 2.84E-05 |

| RknMes02_001781 | AT3G58110 | Unknown protein | 4.715 | 1.34E-06 |

| RknMes02_052316 | AT4G01950 | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 3 | 4.700 | 8.32E-06 |

| RknMes02_001711 | AT4G32460 | Protein of unknown function, DUF642 | 4.685 | 1.13E-06 |

| RknMes02_057300 | AT2G13810 | AGD2-like defense response protein 1 | 4.524 | 1.13E-06 |

| RknMes02_055925 | AT4G34135 | UDP-glucosyltransferase 73B2 | 4.435 | 1.80E-06 |

| RknMes02_054888 | AT1G01690 | Putative recombination initiation defects 3 | 4.407 | 5.59E-06 |

| RknMes02_050833 | AT4G39250 | RAD-like 1/RAD-like 6 | 4.361 | 1.48E-06 |

| RknMes02_039148 | Zein-binding | 4.350 | 1.13E-06 | |

| RknMes02_013200 | AT4G34131 | UDP-glucosyl transferase 73B3 | 4.301 | 3.27E-06 |

| RknMes02_055406 | AT5G17350 | Unknown protein | 4.299 | 1.08E-07 |

| RknMes02_057295 | AT4G37770 | 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase 8 | 4.083 | 1.20E-05 |

| RknMes02_001575 | AT4G25640 | Detoxifying efflux carrier 35 | 4.064 | 1.37E-05 |

| RknMes02_057627 | AT4G32480 | Protein of unknown function (DUF506) | 4.056 | 1.66E-05 |

| RknMes02_058010 | AT5G07610 | F-box family protein | 4.005 | 7.95E-06 |

| RknMes02_011864 | Glucosyl/Glucuronosyl transferase | 3.971 | 3.36E-06 | |

| RknMes02_057486 | AT2G21220 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | 3.878 | 2.98E-07 |

| RknMes02_024608 | AT3G04620 | Alba DNA/RNA-binding protein | 3.876 | 2.89E-05 |

| RknMes02_054063 | AT1G14440 | Homeobox protein 33///homeobox protein 31 | 3.836 | 7.51E-05 |

| RknMes02_051551 | AT2G33480 | NAC domain containing protein 41 | 3.799 | 3.89E-06 |

| RknMes02_057805 | AT3G24060 | Plant self-incompatibility protein S1 family | 3.776 | 1.47E-05 |

| RknMes02_048226 | AT3G16380 | Poly(A) binding protein 6 | 3.775 | 1.01E-05 |

| RknMes02_055397 | AT2G26140 | FTSH protease 4 | 3.745 | 7.16E-06 |

| RknMes02_001499 | AT5G54160 | O-methyltransferase 1 | 3.697 | 8.90E-05 |

| RknMes02_004432 | AT5G11420 | Protein of unknown function, DUF642 | 3.646 | 1.65E-06 |

| RknMes02_053062 | AT1G68390 | Core-2/I-branching beta-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase family protein | 3.612 | 6.51E-07 |

| RknMes02_050655 | AT3G04710 | Ankyrin repeat family protein | 3.533 | 5.74E-06 |

| RknMes02_022851 | AT3G47800 | Galactose mutarotase-like superfamily protein | 3.424 | 1.18E-06 |

| RknMes02_026790 | AT2G26870 | Non-specific phospholipase C2 | 3.386 | 6.01E-08 |

| RknMes02_051740 | AT1G54115 | Cation calcium exchanger 4 | 3.375 | 1.66E-06 |

| RknMes02_054668 | AT4G36740 | Homeobox protein 40///homeobox protein 21 | 3.366 | 1.46E-06 |

| RknMes02_053782 | AT4G17380 | MUTS-like protein 4 | 3.333 | 1.34E-05 |

| RknMes02_052163 | AT2G22840 | Growth-regulating factor 1 | 3.294 | 3.76E-05 |

| RknMes02_054016 | AT5G42120 | Concanavalin A-like lectin protein kinase family protein | 3.244 | 1.52E-05 |

AGI code is shown if proteins encoded in each cassava gene (probe ID) have high amino acid sequence similarity (E ≤ 10−5) to Arabidopsis homologs.

Encoded proteins/other features indicate the putative functions of the gene products that are expected from sequence similarity. The information for the NCBI protein reference sequence with the highest sequence similarity to the probes is shown.

Table 5.

List of top 40 cassava genes with higher expression (log2 ratio > 1; FDR < 0.0001) in roots of SAHA-pretreated plants compared with non-SAHA-pretreated plants in the presence of NaCl for 24 h.

| ProbeID | AGI codea | Encoded proteins/other featuresb | log2 ratio {(NaCl 24 h after SAHA 24 h)/(NaCl 24 h after non-SAHA 24 h)} | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RknMes02_057300 | AT2G13810 | AGD2-like defense response protein 1 | 7.049 | 1.13E-06 |

| RknMes02_058115 | AT3G07390 | Auxin-responsive family protein | 5.000 | 2.84E-05 |

| RknMes02_051874 | AT1G13280 | Allene oxide cyclase 4 | 4.707 | 1.70E-07 |

| RknMes02_057486 | AT2G21220 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family | 4.596 | 2.98E-07 |

| RknMes02_052316 | AT4G01950 | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 3 | 4.487 | 8.32E-06 |

| RknMes02_051551 | AT2G33480 | NAC domain containing protein 52 | 4.457 | 3.89E-06 |

| RknMes02_039148 | Zein-binding | 4.044 | 1.13E-06 | |

| RknMes02_058141 | AT3G06720 | Importin alpha isoform 1 | 4.044 | 1.01E-06 |

| RknMes02_055141 | AT2G40210 | AGAMOUS-like 48 | 3.809 | 1.18E-06 |

| RknMes02_055406 | AT5G17350 | Unknown protein | 3.765 | 1.08E-07 |

| RknMes02_057007 | AT5G57620 | Myb domain protein 36 | 3.757 | 3.40E-05 |

| RknMes02_056640 | AT3G11930 | Adenine nucleotide alpha hydrolases-like superfamily protein | 3.720 | 3.24E-06 |

| RknMes02_028787 | AT1G19640 | Jasmonic acid carboxyl methyltransferase | 3.695 | 3.94E-06 |

| RknMes02_057539 | AT5G07610 | F-box family protein | 3.609 | 2.44E-07 |

| RknMes02_054063 | AT1G14440 | Homeobox protein 33/homeobox protein 31 | 3.598 | 7.51E-05 |

| RknMes02_016408 | AT4G36470 | S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferases superfamily protein | 3.550 | 9.03E-06 |

| RknMes02_052163 | AT2G22840 | Growth-regulating factor 1 | 3.540 | 3.76E-05 |

| RknMes02_053062 | AT1G68390 | Core-2/I-branching beta-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase family protein | 3.491 | 6.51E-07 |

| RknMes02_053782 | AT4G17380 | MUTS-like protein 4 | 3.320 | 1.34E-05 |

| RknMes02_055845 | AT3G51880 | High mobility group B2/high mobility group B1 | 3.292 | 1.37E-05 |

| RknMes02_050833 | AT4G39250 | RAD-like 1/RAD-like 6 | 3.292 | 1.48E-06 |

| RknMes02_001711 | AT4G32460 | Protein of unknown function, DUF642 | 3.224 | 1.13E-06 |

| RknMes02_058688 | AT3G28880 | Ankyrin repeat family protein | 3.222 | 4.22E-07 |

| RknMes02_001781 | AT3G58110 | Unknown protein | 3.199 | 1.34E-06 |

| RknMes02_044414 | 3.137 | 2.80E-05 | ||

| RknMes02_054888 | AT1G01690 | Putative recombination initiation defects 3 | 3.128 | 5.59E-06 |

| RknMes02_037654 | AT4G29110 | Unknown protein | 2.989 | 7.18E-06 |

| RknMes02_055397 | AT2G26140 | FTSH protease 4 | 2.940 | 7.16E-06 |

| RknMes02_052664 | AT5G64310 | Arabinogalactan protein 1 | 2.918 | 4.99E-05 |

| RknMes02_001499 | AT5G54160 | O-methyltransferase 1 | 2.918 | 8.90E-05 |

| RknMes02_012269 | AT1G06460 | Alpha-crystallin domain 32.1 | 2.841 | 7.23E-05 |

| RknMes02_051562 | AT5G64360 | Chaperone DnaJ-domain superfamily protein | 2.832 | 5.97E-08 |

| RknMes02_014532 | AT1G17020 | Senescence-related gene 1 | 2.798 | 3.67E-05 |

| RknMes02_051803 | AT3G09270 | Glutathione S-transferase TAU 8/glutathione S-transferase tau 7 | 2.770 | 1.29E-05 |

| RknMes02_006016 | 2.766 | 9.03E-06 | ||

| RknMes02_051840 | AT3G09280 | Unknown protein | 2.697 | 2.61E-05 |

| RknMes02_013200 | AT4G34131 | UDP-glucosyl transferase 73B3 | 2.665 | 3.27E-06 |

| RknMes02_019058 | AT1G80050 | Adenine phosphoribosyl transferase 2 | 2.655 | 3.44E-06 |

| RknMes02_012739 | AT2G18550 | Homeobox protein 21 | 2.639 | 2.53E-06 |

AGI code is shown if proteins encoded in each cassava gene (probe ID) have high amino acid sequence similarity (E ≤ 10−5) to Arabidopsis homologs.

Encoded proteins/other features indicate the putative functions of the gene products that are expected from sequence similarity. The information for the NCBI protein reference sequence with the highest sequence similarity to the probes is shown.

Table 4.

List of top 40 cassava genes with higher expression (log2 ratio > 1; FDR < 0.0001) in roots of SAHA-pretreated plants compared with non-SAHA-pretreated plants in the presence of NaCl for 2 h.

| ProbeID | AGI codea | Encoded proteins/other featuresb | log2 ratio {(NaCl 2 h after SAHA 24 h)/(NaCl 2 h after non-SAHA 24 h)} | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RknMes02_057300 | AT2G13810 | AGD2-like defense response protein 1 | 7.348 | 1.13E-06 |

| RknMes02_058141 | AT3G06720 | Importin alpha isoform 1 | 6.563 | 1.01E-06 |

| RknMes02_051874 | AT1G13280 | Allene oxide cyclase 4 | 5.966 | 1.70E-07 |

| RknMes02_052316 | AT4G01950 | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 3 | 5.717 | 8.32E-06 |

| RknMes02_055141 | AT2G40210 | AGAMOUS-like 48 | 5.695 | 1.18E-06 |

| RknMes02_058688 | AT3G28880 | Ankyrin repeat family protein | 5.456 | 4.22E-07 |

| RknMes02_050833 | AT4G39250 | RAD-like 1/RAD-like 6 | 5.386 | 1.48E-06 |

| RknMes02_009639 | AT1G34300 | Lectin protein kinase family protein | 5.369 | 1.57E-05 |

| RknMes02_053062 | AT1G68390 | Core-2/I-branching beta-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase family protein | 5.273 | 6.51E-07 |

| RknMes02_057007 | AT5G57620 | Myb domain protein 36 | 5.228 | 3.40E-05 |

| RknMes02_058115 | AT3G07390 | Auxin-induced in root cultures 12 | 5.167 | 2.84E-05 |

| RknMes02_058010 | AT5G07610 | F-box family protein | 4.974 | 7.95E-06 |

| RknMes02_053766 | AT4G33870 | Peroxidase superfamily protein | 4.907 | 1.74E-05 |

| RknMes02_001711 | AT4G32460 | Protein of unknown function, DUF642 | 4.892 | 1.13E-06 |

| RknMes02_057698 | AT2G45400 | NAD(P)-binding Rossmann-fold superfamily protein | 4.872 | 3.32E-06 |

| RknMes02_051856 | AT1G35910 | Trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase | 4.833 | 4.21E-05 |

| RknMes02_050655 | AT3G04710 | Ankyrin repeat family protein | 4.790 | 5.74E-06 |

| RknMes02_054888 | AT1G01690 | Putative recombination initiation defects 3 | 4.788 | 5.59E-06 |

| RknMes02_055406 | AT5G17350 | Unknown protein | 4.768 | 1.08E-07 |

| RknMes02_001781 | AT3G58110 | Unknown protein | 4.741 | 1.34E-06 |

| RknMes02_054063 | AT1G14440 | Homeobox protein 33/homeobox protein 31 | 4.683 | 7.51E-05 |

| RknMes02_052664 | AT5G64310 | Arabinogalactan protein 1 | 4.529 | 4.99E-05 |

| RknMes02_037315 | AT4G00330 | Calmodulin-binding receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase 2 | 4.438 | 1.88E-06 |

| RknMes02_051803 | AT3G09270 | Glutathione S-transferase TAU 8 | 4.369 | 1.29E-05 |

| RknMes02_037654 | AT4G29110 | Unknown protein | 4.337 | 7.18E-06 |

| RknMes02_051464 | AT3G06240 | F-box family protein | 4.284 | 2.95E-06 |

| RknMes02_053782 | AT4G17380 | MUTS-like protein 4 | 4.231 | 1.34E-05 |

| RknMes02_049288 | AT5G52060 | BCL-2-associated athanogene 1 | 4.218 | 2.22E-05 |

| RknMes02_000416 | AT2G26870 | Non-specific phospholipase C2 | 4.138 | 1.20E-07 |

| RknMes02_051638 | AT4G22660 | F-box family protein with a domain of unknown function (DUF295) | 4.008 | 5.43E-05 |

| RknMes02_051551 | AT2G33480 | NAC domain containing protein 52 | 3.998 | 3.89E-06 |

| RknMes02_052689 | AT5G16080 | Carboxyesterase 17 | 3.989 | 3.58E-05 |

| RknMes02_020256 | AT3G19270 | Cytochrome P450, family 707, subfamily A, polypeptide 4 | 3.985 | 3.39E-05 |

| RknMes02_011799 | AT2G28090 | Heavy metal transport/detoxification superfamily protein | 3.984 | 4.66E-05 |

| RknMes02_055845 | AT3G51880 | High mobility group B2/high mobility group B1 | 3.974 | 1.37E-05 |

| RknMes02_007372 | Heavy metal transport/detoxication domain-containing protein-related | 3.962 | 3.23E-05 | |

| RknMes02_051562 | AT5G64360 | Chaperone DnaJ-domain superfamily protein | 3.929 | 5.97E-08 |

| RknMes02_054294 | AT1G67810 | Sulfur E2 | 3.918 | 8.44E-07 |

| RknMes02_056535 | AT5G53980 | Homeobox protein 52 | 3.912 | 3.92E-06 |

| RknMes02_055397 | AT2G26140 | FTSH protease 4 | 3.786 | 7.16E-06 |

AGI code is shown if proteins encoded in each cassava gene (probe ID) have high amino acid sequence similarity (E ≤ 10−5) to Arabidopsis homologs.

Encoded proteins/other features indicate the putative functions of the gene products that are expected from sequence similarity. The information for the NCBI protein reference sequence with the highest sequence similarity to the probes is shown.

In the case of the HDAC inhibitor Ky-2, 72.9% of the HDAC inhibitor-inducible genes are salt-responsive genes in Arabidopsis (Sako et al., 2016). In contrast, 28.3% of SAHA-upregulated genes are high salinity stress-responsive (Figure S2A), and only 27 SAHA-upregulated genes were upregulated by high-salinity stress (2 and/or 24 h NaCl treatment; Table 6). In mangrove plants, lignin accumulation functions in blocking metal-ion influx with higher suberization, suggesting that lignification can prohibit ions from flowing inside (Cheng et al., 2014). We analyzed the following three genes that are believed to play critical roles in regulating lignin accumulation: L-phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), and caffeic acid 3-Omethyltransferase (COMT) genes (Whetten and Sederoff, 1995; Ma and Xu, 2008; Nguyen et al., 2016). Among them, the expression of only COMT was significantly enhanced by SAHA treatment (Figure S3), suggesting that the lignin accumulation might be changed by overexpression of COMT induced by SAHA treatment and block ion uptake.

Table 6.

List of 27 SAHA-upregulated and high-salinity-stress-upregulated genes (log2 ratio > 1; FDR < 0.0001) in roots.

| Probe ID | AGI Codea | Encoded proteins/other featuresb | Log2 ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAHA 24 h/non-treated | w/o SAHAc | ||||

| 2 h NaCl/0 h NaCl | 24 h NaCl/0 h NaCl | ||||

| RknMes02_048392 | AT2G38940 | Phosphate transporter 1;4 | 4.837 | 2.503 | 2.986 |

| RknMes02_048720 | AT1G03790 | Tandam CCCH zinc finger protein4 | 2.912 | 2.844 | 1.541 |

| RknMes02_022193 | AT1G67810 | Sulfur E2 | 2.217 | 1.650 | 1.967 |

| RknMes02_049538 | AT1G74650 | Myb domain protein 31 | 1.903 | 2.312 | 2.343 |

| RknMes02_049529 | AT3G54420 | Chitinase class IV | 1.733 | 3.678 | 5.653 |

| RknMes02_009426 | AT5G14860 | UDP-Glycosyltransferase superfamily protein | 1.668 | 2.277 | 2.641 |

| RknMes02_004082 | AT1G17840 | ATP-binding cassette G11 | 1.617 | 1.030 | 1.541 |

| RknMes02_057376 | 1.616 | 2.369 | 1.867 | ||

| RknMes02_029383 | AT2G41190 | Transmembrane amino acid transporter family protein | 1.580 | 2.052 | 2.285 |

| RknMes02_023158 | AT5G02230 | Haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase (HAD) superfamily protein | 1.578 | 1.794 | 1.288 |

| RknMes02_005365 | AT2G37980 | O-fucosyltransferase family protein | 1.551 | 2.893 | 1.568 |

| RknMes02_034114 | AT5G26667 | PYR6 | 1.529 | 1.525 | 1.991 |

| RknMes02_049514 | AT5G02230 | Haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase (HAD) superfamily protein | 1.408 | 1.462 | 1.008 |

| RknMes02_036843 | AT2G30860 | Glutathione S-transferase PHI 9 | 1.403 | 1.735 | 1.360 |

| RknMes02_019499 | 1.382 | 1.791 | 1.452 | ||

| RknMes02_054233 | AT5G42200 | RING/U-box superfamily protein | 1.378 | 3.304 | 2.829 |

| RknMes02_028518 | AT5G05690 | Cytochrome P450 90A1 | 1.292 | 2.265 | 1.357 |

| RknMes02_056529 | AT2G37980 | O-fucosyltransferase family protein | 1.288 | 2.722 | 1.424 |

| RknMes02_049315 | AT1G13990 | Unknown protein | 1.274 | 2.322 | 1.425 |

| RknMes02_008877 | AT4G31240 | Nucleoredoxin2 | 1.266 | 5.793 | 5.162 |

| RknMes02_015088 | AT1G13990 | Unknown protein | 1.212 | 2.360 | 1.508 |

| RknMes02_040118 | AT3G07130 | Purple acid phosphatase 15 | 1.195 | 2.667 | 2.143 |

| RknMes02_036162 | AT1G21790 | TRAM, LAG1 and CLN8 (TLC) lipid-sensing domain containing protein | 1.179 | 2.241 | 1.159 |

| RknMes02_024400 | Arginine decarboxylase/L-arginine carboxy-lyase | 1.143 | 2.592 | 2.085 | |

| RknMes02_027987 | AT1G60420 | Nucleoredoxin1 | 1.097 | 5.659 | 5.143 |

| RknMes02_010471 | AT3G54100 | O-fucosyltransferase family protein | 1.086 | 2.717 | 1.854 |

| RknMes02_036257 | AT5G23240 | DNAJ protein C76 | 1.010 | 1.510 | 1.065 |

AGI code is shown if proteins encoded in each cassava gene (probe ID) have high amino acid sequence similarity (E ≤ 10−5) to Arabidopsis homologs.

Encoded proteins/other features indicate the putative functions of the gene products that are expected from sequence similarity. The information for the NCBI protein reference sequence with the highest sequence similarity to the probes is shown.

Plants that were not pretreated with SAHA were used.

SAHA treatment decreased the expression of 141 high salinity stress-responsive genes including cell wall-related genes such as beta-galactosidases (RknMes02_003559, cassava4.1_001503m; RknMes02_030412, cassava4.1_001733m; RknMes02_034218, cassava4.1_001885m), beta-glucosidase (RknMes02_058028, cassava4.1_032518m), pectin lyase (RknMes02_051310, cassava4.1_021247m), pectinesterase (RknMes02_057990, cassava4.1_032455m), and pectin methylesterase inhibitor 4 (RknMes02_055023, cassava4.1_027551m) (Figure S2, Table S9). The decreased expression of these genes might contribute to changes in cell-wall components caused by SAHA treatment (see Discussion).

Discussion

Here we demonstrated that the HDAC inhibitor, SAHA, can decrease sodium ion content particularly in the stems, resulting in increased survival rates under high salinity stress conditions in cassava. Transcriptome analysis identified candidate genes, such as an allene oxide cyclase catalyzing an essential step in the biosynthesis of JA, whose expression is strongly upregulated by SAHA. This study shows evidence that the HDAC inhibitor is an effective small molecule for alleviating salinity stress in crops, and will improve understanding of the mechanisms by which histone acetylation regulates response to abiotic stress in cassava. In this study, we identified many salinity stress-upregulated genes in cassava. This study is the first report on the transcriptome analysis using microarray under high-salinity stress in cassava and the information will be useful for the development of high-salinity stress tolerant cassava plants.

This study showed that SAHA treatment reduced Na+ concentration in both stems and leaves. Plants are able to survive high salinity stress conditions by the maintenance of K+ and Na+ homeostasis using several transporters (Zhu, 2003; Ji et al., 2013; Julkowska and Testerink, 2015). Several transporters function in the alleviation of high-salinity stress. SOS1 encodes the plasma-membrane Na+/H+ antiporter. Its activity can be detected only during salt stress conditions and is mediated by the Ca2+-responsive SOS3-SOS2 protein kinase complex (Qiu et al., 2002). When plants are exposed to high salinity stress conditions, SOS1 functions in the control of Na+ efflux to maintain ion homeostasis. When the expression of SOS1 is constitutively driven in Arabidopsis, the overexpressors become considerably tolerant to salt stress (Shi et al., 2003). In the woody plant Populus, introduction of the constitutively active SOS2 isoform with induced expression of SOS1 can enhance tolerance to salinity stress (Zhou et al., 2014). Plants also prevent excessive Na+ in cells by Na+ compartmentation by Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (NHX1). NHX1 functions to compartmentalize Na+ in the vacuole, resulting in low Na+ concentration and thus adjusting osmotic pressure to maintain water uptake. In Arabidopsis, co-expression of SOS1 and NHX1 enhances tolerance to NaCl concentrations up to 250 mM, suggesting the crucial functions of these genes. Furthermore, high-affinity K+ transporters (HKT) play an important role in Na+ exclusion from leaves in monocots and dicots. The overexpression of AtHKT1;1 improves salt tolerance in Arabidopsis (Horie et al., 2009; Mølle et al., 2009). Our transcriptome analysis did not find significant alteration of their mRNA expression (data not shown).

Screening of HDAC inhibitors that may induce higher expression of genes for ion transporters (e.g., NHX1 and HKT) is of interest as it may help to improve salt tolerance in cassava. HDACs in plants can be separated into three distinct families. The largest family is type I (RPD3-like), which consists of Zn2+-dependent deacetylases and is classified into three classes (I, II, and IV; Yang and Seto, 2008; Seto and Yoshida, 2014). They are generally conserved in eukaryotes, and there are 12 and 6 putative members in Arabidopsis (Hollender and Liu, 2008) and cassava (Figure S4), respectively. The second group of HDACs is plant-specific, and consists of HD-tuins. Four HD-tuins (HDT1-4) and 3 putative HD-tuins have been identified in Arabidopsis and cassava, respectively (Figure S4). The last group consists of homologs to the yeast Sir2 protein, which is a NAD+-dependent deacetylase. Two sirtuin proteins, SRT1 and SRT2 have been found in Arabidopsis (Hollender and Liu, 2008). Two putative sirtuins have been identified in cassava (Figure S4). HDAC inhibitors including Trichostatin A, SAHA, and sodium butyrate, whose target is Zn2+-dependent deacetylase, do not inhibit sirtuin activity (Richon, 2006). SAHA and related hydroxamic acid-based HDAC inhibitors have inhibitory effects on class I (HDAC1, 2, 3 and 8), class II (HDAC4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10), and class IV (HDAC11) human HDACs (Bolden et al., 2006). SAHA is a non-class selective inhibitor. Different selective inhibitors might be valuable for increasing tolerance to salt stress in cassava, because different gene sets are activated based on class or type selectivity of HDAC inhibitors and transcript abundance is also changed depending on inhibitory efficiency of each HDAC.

SAHA treatment strongly induced the mRNA expression of MeAOC4. AOC regulates a crucial step in JA biosynthesis, and the JA derivative, MeJA, alleviates salt stress in soybean (Yoon et al., 2009). The constitutive expression of AOCs can confer salinity tolerance to plants such as tobacco cell lines (Yamada et al., 2002) and wheat (Zhao et al., 2014), and references for the involvement of JA in environmental stresses can be found in Riemann et al. (2015). In light of these findings, it is highly possible that overexpression of MeAOC4 contributes to increased tolerance to salt stress under SAHA treatment in cassava. AOC enzyme activity is altered by heteromerization with its own isomers, and the specific heteromerized pair AtAOC2 and AtAOC4 shows the highest activity of the four AOC proteins in Arabidopsis (Otto et al., 2016). As tissue-specific expression of AOC genes is observed in Arabidopsis (Stenzel et al., 2012), each AOC seems to be regulated in a tissue- or environmental-stress specific manner in cassava. Our transcriptomic data reveal that MeAOC4 is not salt-responsive under our growth conditions and might be specifically expressed in a tissue such as flower or tuber that we have not analyzed. SAHA treatment induced the expression of MeAOC4, which might allow heteromerization of artificially induced MeAOC4 with salt-induced MeAOC3-2, and play a pivotal role in increased tolerance under SAHA treatment.

Author contributions

OP, MU, and MS designed the experiments; OP, MU, MI, YK, YU, AM, MT, CU, and HS conducted the experiments; OP, MU, YU, and AM analyzed the data; OP, MU, MY, JN, and MS wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to show our appreciation to Ms. E. Moriya, Ms. Y. Okamoto, and Ms. K. Mizunashi for their kind experimental support. OP was supported by RIKEN as an International Program Associate (IPA). This work was supported by the grant to MU from RIKEN and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (KAKENHI grant No. 25650126), and grants to MS from RIKEN, the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) [Core Research for Evolutionary Science and Technology (CREST)], and Innovative Areas Grant No. 16H01476 and Challenging Exploratory Research Grant No. 16K14832 of the Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, and Technology of Japan.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.02039/full#supplementary-material

References

- Apse M. P., Aharon G. S., Snedden W. A., Blumwald E. (1999). Salt tolerance conferred by overexpression of a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiport in Arabidopsis. Science 285, 1256–1258. 10.1126/science.285.5431.1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asensi-Fabado M. A., Amtmann A., Perrella G. (2016). Plant responses to abiotic stress: The chromatin context of transcriptional regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolden J. E., Peart M. J., Johnstone R. W. (2006). Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 769–784. 10.1038/nrd2133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretero C. L., Cantos M., García J. L., Azcón R., Troncoso A. (2008). Arbuscular-mycorrhizal contributes to alleviation of salt damage in cassava clones. J. Plant Nutr. 31, 959–971. 10.1080/01904160802043296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Jiang Z. Y., Liu Y., Ye Z. H., Wu M. L., Sun C. C., et al. (2014). Metal (Pb, Zn and Cu) uptake and tolerance by mangroves in relation to root anatomy and lignification/suberization. Tree Physiol. 34, 646–656. 10.1093/treephys/tpu042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokmanovic M., Clarke C., Marks P. A. (2007). Histone deacetylase inhibitors: overview and perspectives. Mol. Cancer Res. 5, 981–989. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egert A., Keller F., Peters S. (2013). Abiotic stress-induced accumulation of raffinose in Arabidopsis leaves is mediated by a single raffinose synthase (RS5, At5g40390). BMC Plant Biol. 13:218. 10.1186/1471-2229-13-218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElSayed A. I., Rafudeen M. S., Golldack D. (2014). Physiological aspects of raffinose family oligosaccharides in plants: protection against abiotic stress. Plant Biol. (Stuttg). 16, 1–8. 10.1111/plb.12053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sharkawy M. A. (2004). Cassava biology and physiology. Plant Mol. Biol. 56, 481–501. 10.1007/s11103-005-2270-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (1998). Storage and Processing of Roots and Tubers in the Tropics [Online]. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/x5415e/x5415e01.htm (Accessed 21 July, 2016).

- Fu L., Ding Z., Han B., Hu W., Li Y., Zhang J. (2016). Physiological investigation and transcriptome analysis of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-induced dehydration stress in cassava. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:283. 10.3390/ijms17030283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollender C., Liu Z. (2008). Histone deacetylase genes in Arabidopsis development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50, 875–885. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie T., Hauser F., Schroeder J. I. (2009). HKT transporter-mediated salinity resistance mechanisms in Arabidopsis and monocot crop plants. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 660–668. 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itouga M., Kato Y., Sakakibara H. (2014). Phenotypic plasticity and mineral nutrient uptake of the moss Polytrichum commune Hedw. (Polytrichaceae, Bryophyta) during acclimation to a change in light intensity. Hikobia 16, 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Jakab G., Ton J., Flors V., Zimmerli L., Metraux J. P., Mauch-Mani B. (2005). Enhancing Arabidopsis salt and drought stress tolerance by chemical priming for its abscisic acid responses. Plant Physiol. 139, 267–274. 10.1104/pp.105.065698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H., Pardo J. M., Batelli G., Van Oosten M. J., Bressan R. A., Li X. (2013). The salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway: established and emerging roles. Mol. Plant 6, 275–286. 10.1093/mp/sst017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Shao M., He Y., Guan R., Chu P., Jiang H. (2015). Proteome dynamics and physiological responses to short-term salt stress in Brassica napus leaves. PLoS ONE 10:e0144808. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julkowska M. M., Testerink C. (2015). Tuning plant signaling and growth to survive salt. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 586–594. 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldis A., Tsementzi D., Tanriverdi O., Vlachonasios K. E. (2010). Arabidopsis thaliana transcriptional co-activators ADA2b and SGF29a are implicated in salt stress responses. Planta 233, 749–762. 10.1007/s00425-010-1337-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. M., Sasaki T., Ueda M., Sako K., Seki M. (2015). Chromatin changes in response to drought, salinity, heat, and cold stresses in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6:114. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishor P., Hong Z., Miao G. H., Hu C., Verma D. (1995). Overexpression of [delta]-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase increases proline production and confers osmotolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol. 108, 1387–1394. 10.1104/pp.108.4.1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q. H., Xu Y. (2008). Characterization of a caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase from wheat and its function in lignin biosynthesis. Biochimie 90, 515–524. 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Gong Q., Bohnert H. J. (2006). Dissecting salt stress pathways. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1097–1107. 10.1093/jxb/erj098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui A., Ishida J., Morosawa T., Mochizuki Y., Kaminuma E., Endo T. A., et al. (2008). Arabidopsis transcriptome analysis under drought, cold, high-salinity and ABA treatment conditions using a tiling array. Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 1135–1149. 10.1093/pcp/pcn101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKersie B. D., Bowley S. R., Jones K. S. (1999). Winter survival of transgenic alfalfa overexpressing superoxide dismutase. Plant Physiol. 119, 839–848. 10.1104/pp.119.3.839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mølle I. S., Gilliham M., Jha D., Mayo G. M., Roy S. J., Coates J. C., et al. (2009). Shoot Na+ exclusion and increased salinity tolerance engineered by cell type-specific alteration of Na+ transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 2163–2178. 10.1105/tpc.108.064568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R., Tester M. (2008). Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–681. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant 15, 473–497. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. N., Son S., Jordan M. C., Levin D. B., Ayele B. T. (2016). Lignin biosynthesis in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): its response to waterlogging and association with hormonal levels. BMC Plant Biol. 16:28. 10.1186/s12870-016-0717-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwamanya E., Baguma Y., Kawuki R., Rubaihayo P. (2008). Quantification of starch physicochemical characteristics in a cassava segregating population. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 16, 191–202. 10.4314/acsj.v16i3.54380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen K. M., Schaal B. A. (1999). Evidence on the origin of cassava: phylogeography of Manihot esculenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5586–5591. 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M., Naumann C., Brandt W., Wasternack C., Hause B. (2016). Activity regulation by heteromerization of Arabidopsis allene oxide cyclase family members. Plants (Basel) 5:3. 10.3390/plants5010003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi Y., Jiang K., Cao Y., Wang Q., Huang Z., Li L., et al. (2009). Allene oxide cyclase from Camptotheca acuminata improves tolerance against low temperature and salt stress in tobacco and bacteria. Mol. Biotechnol. 41, 115–122. 10.1007/s12033-008-9106-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Q. S., Guo Y., Dietrich M. A., Schumaker K. S., Zhu J. K. (2002). Regulation of SOS1, a plasma membrane Na+/H+ exchanger in Arabidopsis thaliana, by SOS2 and SOS3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8436–8441. 10.1073/pnas.122224699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richon V. M. (2006). Cancer biology: mechanism of antitumour action of vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid), a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor. Br. J. Cancer 95, S2–S6. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann M., Dhakarey R., Hazman M., Miro B., Kohli A., Nick P. (2015). Exploring jasmonates in the hormonal network of drought and salinity responses. Front Plant Sci. 6:1077. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxas V. P., Smith R. K., Jr., Allen E. R., Allen R. D. (1997). Overexpression of glutathione S-transferase/glutathione peroxidase enhances the growth of transgenic tobacco seedlings during stress. Nat. Biotechnol. 15, 988–991. 10.1038/nbt1097-988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto A., Murata A. N. (1998). Metabolic engineering of rice leading to biosynthesis of glycinebetaine and tolerance to salt and cold. Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 1011–1019. 10.1023/A:1006095015717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako K., Kim J. M., Matsui A., Nakamura K., Tanaka M., Kobayashi M., et al. (2016). Ky-2, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, enhances high-salinity stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 776–783. 10.1093/pcp/pcv199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto E., Yoshida M. (2014). Erasers of histone acetylation: the histone deacetylase enzymes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 6:a018713. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakirova F. M., Sakhabutdinova A. R., Bezrukova M. V., Fatkhutdinova R. A., Fatkhutdinova D. R. (2003). Changes in the hormonal status of wheat seedlings induced by salicylic acid and salinity. Plant Sci. 164, 317–322. 10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00415-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Conde e Silva N., Audonnet L., Servet C., Wei W., Zhou D. X. (2014). Over-expression of histone H3K4 demethylase gene JMJ15 enhances salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 5:290. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Lee B. H., Wu S. J., Zhu J. K. (2003). Overexpression of a plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter gene improves salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 81–85. 10.1038/nbt766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde S., Nurul Islam M., Ng C. K. (2012). Dehydration stress-induced oscillations in LEA protein transcripts involves abscisic acid in the moss, Physcomitrella patens. New Phytol. 195, 321–328. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel I., Otto M., Delker C., Kirmse N., Schmidt D., Miersch O., et al. (2012). ALLENE OXIDE CYCLASE (AOC) gene family members of Arabidopsis thaliana: tissue- and organ-specific promoter activities and in vivo heteromerization. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 6125–6138. 10.1093/jxb/ers261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsumi Y., Tanaka M., Kurotani A., Yoshida T., Mochida K., Matsui A., et al. (2016). Cassava (Manihot esculenta) transcriptome analysis in response to infection by the fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides using an oligonucleotide-DNA microarray. J. Plant Res. 129, 711–726. 10.1007/s10265-016-0828-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsumi Y., Tanaka M., Morosawa T., Kurotani A., Yoshida T., Mochida K., et al. (2012). Transcriptome analysis using a high-density oligomicroarray under drought stress in various genotypes of cassava: an important tropical crop. DNA Res. 19, 335–345. 10.1093/dnares/dss016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdin E., Ott M. (2015). 50 years of protein acetylation: from gene regulation to epigenetics, metabolism and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 258–264. 10.1038/nrm3931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten R., Sederoff R. (1995). Lignin Biosynthesis. Plant Cell 7, 1001–1013. 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Duan X., Wang B., Hong B., Ho T., Wu R. (1996). Expression of a late embryogenesis abundant protein gene, HVA1, from barley confers tolerance to water deficit and salt stress in transgenic rice. Plant Physiol. 110, 249–257. 10.1104/pp.110.1.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada A., Saitoh T., Mimura T., Ozeki Y. (2002). Expression of mangrove allene oxide cyclase enhances salt tolerance in Escherichia coli, yeast, and tobacco cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 903–910. 10.1093/pcp/pcf108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Chen Z. Z., Zhou X. F., Yin H. B., Li X., Xin X. F., et al. (2009). Overexpression of SOS (Salt Overly Sensitive) genes increases salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2, 22–31. 10.1093/mp/ssn058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. J., Seto E. (2008). The Rpd3/Hda1 family of lysine deacetylases: from bacteria and yeast to mice and men. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 206–218. 10.1038/nrm2346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J. Y., Hamayun M., Lee S. K., Lee I. J. (2009). Methyl jasmonate alleviated salinity stress in soybean. J. Crop Sci. Biotech. 12, 63–68. 10.1007/s12892-009-0060-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y., Zhang M., Zhang J., Duan L., Li Z. (2012). SOS1 gene overexpression increased salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco by maintaining a higher K+/Na+ ratio. J. Plant Physiol. 169, 255–261. 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Dong W., Zhang N., Ai X., Wang M., Huang Z., et al. (2014). A wheat allene oxide cyclase gene enhances salinity tolerance via jasmonate signaling. Plant Physiol. 164, 1068–1076. 10.1104/pp.113.227595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]