Abstract

Telomerase synthesizes telomeric DNA by copying a short template sequence within its telomerase RNA component. We delineated nucleotides and base-pairings within a previously mapped central domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase RNA (TLC1) that are important for telomerase function and for binding to the telomerase catalytic protein Est2p. Phylogenetic comparison of telomerase RNA sequences from several budding yeasts revealed a core structure common to Saccharomyces and Kluyveromyces yeast species. We show that in this structure three conserved sequences interact to provide a binding site for Est2p positioned near the template. These results, combined with previous studies on telomerase RNAs from other budding yeasts, vertebrates, and ciliates, define a minimal universal core for telomerase RNAs.

Keywords: pseudoknot, secondary structure, yeast Est2p, yeast TLC1

Telomerase (TER) synthesizes telomeric DNA by copying a short template sequence within its TER RNA component by using a reverse transcription mechanism. The catalytic chemistry of the nucleic acid polymerization reaction is carried out by the active site of TER reverse transcriptase (TERT), the protein subunit of the core TER enzyme. TERT protein includes a domain containing the characteristic amino acid motifs of conventional reverse transcriptases (1, 2). In addition, the RNA component of TER forms an integral and essential part of the enzyme (3). The effects of TER RNA mutations provide evidence for functions of the TER RNA beyond simply providing the short template sequence; essential bases outside the template have been identified as critical for various aspects of the TER enzymatic functions, defining TER as a true ribonucleoprotein enzyme (4).

TER RNAs have diverged rapidly in evolution, with respect to both size and overall sequence. Recent studies of vertebrate, ciliate, and budding yeast TER RNAs have advanced the understanding of their structure and function. The ≈150- to ≈450-base-long protozoan and vertebrate TER RNAs share elements of a conserved core secondary structure (5–7). One element in that core structure, a pseudoknot, has been shown to be essential for the stable association of the reverse transcriptase protein TERT with the RNA in ciliate (Tetrahymena) TER and for TER function in vivo and in vitro (8–10). In the vertebrate TER, a pseudoknot domain was similarly shown to be important for TERT protein binding to the TER RNA (11). Mutations in the conserved stem 2 [called pairing 3 or P3 (5)] of the pseudoknot that disrupt its primary sequence or its structure disrupt TER activity (3, 12–14). A long-range base-pairing element that encloses the templating and pseudoknot domains is also common to the vertebrate and ciliate TER RNA core secondary structure (5, 7). Another long-range base-pairing has been identified immediately upstream of the templating domain in yeast TER RNAs. This structure demarcates the boundary of the TER RNA template by limiting the extent of polymerization along the RNA (15, 16).

The ≈930–1,300 nucleotide-long TER RNAs of Kluyveromyces and Saccharomyces budding yeasts are much larger than those of ciliates and vertebrates. Using phylogenetic and mutagenic analyses, we previously defined four highly conserved, essential primary sequence elements, all outside the templating domain, in the Kluyveromyces yeasts. Two of these conserved primary sequences, CS3 and CS4, which comprise loop 1 and stem 2 of a pseudoknot, are necessary for TER activity and for correct template usage (15, 17). The other two conserved sequences previously identified among the yeast TER RNAs are CS2, a binding site for Est1p, a component of the TER holoenzyme complex (18), and CS7, a binding site for the Sm protein complex (19). However, owing to the large sizes and the extent of sequence divergence of budding yeast TER RNAs, it was not previously known whether they share a core secondary structure with the vertebrate and ciliate TER RNAs.

Here we report investigations of the TER RNA of budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, aimed at further identifying and analyzing sequences and structures important for TER function and TERT protein (Est2p in S. cerevisiae) binding. We also analyzed the sequences of six Saccharomyces budding yeasts, including S. cerevisiae, for conservation of sequences and possible structures. We report that the Saccharomyces TERs also contain conserved sequences CS3 and CS4, which were shown previously to form an essential pseudoknot in six Kluyveromyces budding yeasts (17). We propose a core structure that is conserved between the Saccharomyces and Kluyveromyces yeasts and, as in the ciliate and vertebrate TER RNAs, includes a long-range base-pairing element that encloses the TERT-binding site and the templating domains. This core structure agrees with structure predictions independently reported recently for Saccharomyces yeasts TER RNA while this work was under review for publication (20, 21). Here, we also test this structure experimentally by mutagenic studies. We further delineate the critical bases and structures necessary for yeast TERT (Est2p) binding to TER RNA; the most critical element is the paired CS3–CS4 structure. Combining this new information with previously reported data, we propose a universal minimal core structure and TERT-interaction region for TER RNA.

Methods

Yeast Strain Construction. Yeast strain yEHB1002 (MATα ade2::hisG his3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 met15Δ0 trp1Δ63 ura3Δ0 tlc1::TRP1pRS316TLC1) was constructed by disrupting the TLC1 gene with TRP1 (22). The strain carries a CEN/ARS, URA3 plasmid containing the wild-type TLC1 with its endogenous promoter and terminator (pRS316TLC1).

Southern Blot Analysis of Telomeres. Strain yEHB1002, carrying pRS316TLC1, was transformed with various mutant TLC1 plasmids. Cells were grown in -Ura-His medium to keep both the wild-type and mutant plasmids (streak 0), or streaked on 5-fluoroorotic acid-His to select against the wild-type TLC1 (streak 1). Cells were then streaked on -His plates continuously. Genomic DNA was prepared from cells after certain numbers of streaks as indicated, digested with XhoI, and separated on 0.8% agarose gels. DNA was transferred from gels to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and hybridized with a γ-32P-end-labeled wildtype telomeric repeat oligonucleotide (22).

Immunoprecipitation and Northern Blot Analysis. Cells containing the mutant TLC1 plasmid (streak 2) were transformed with a 2μ plasmid that carries a 13myc tag Est2p at its C terminus (pRS426Est2myc) and were grown to OD600 = 0.4. Extracts were prepared in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0/150 mM NaCl/2 mM EDTA/2 mM EGTA/0.1%Nonidet P-40/10% glycerol and protease inhibitors from Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and protein concentration was quantified by the Bradford method. Equal amounts of total protein (typically ≈2 mg) were immunoprecipitated with 30 μl of 50% α-myc matrix (clone 9E10 from Covance Research Products, Berkeley, CA) in the presence of 0.2 unit/μl Rnasin (Promega) in 300 μl total volume at 4°Cfor2hwith shaking. The beads were washed three times with the lysis buffer. RNA was prepared from the total lysate and from the beads.

For Northern blot analysis, RNA prepared from the lysates (equivalent of 10% of the amount used for immunoprecipitation) and beads were run on 1.3% agarose gels, transferred to Hybond N-XL membrane (Amersham Biosciences), and hybridized to a TLC1 probe labeled by random priming with [α-32P]dCTP.

Results

A Series of Deletion Mutations in the Central Region of S. cerevisiae TER RNA (TLC1). A central region of ≈430 nt in the S. cerevisiae TER RNA (TLC1) was previously identified as essential for its function through selection for viable tlc1 deletion alleles (23). In that study, two deletion mutants in the central essential region each resulted in a senescent phenotype (23). We first tested whether, within this essential central region of TLC1, some sequences are dispensable for function by performing finer-level analyses of this central core region by using deletions and scanning substitutions.

A series of 11 mutants deleting various regions in TLC1 between nucleotides 495 and 880 was constructed (Fig. 1 A and B and Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These mutant tlc1 genes were cloned into a CEN/ARS plasmid containing the endogenous TLC1 promoter and terminator. To examine in vivo function, each mutant plasmid was transformed into a yeast strain with the chromosomal TLC1 deleted, carrying a wild-type TLC1 gene on a URA3-based plasmid (pRS316TLC1). This wild-type TLC1 plasmid was shuffled out by counterselection on 5-fluoroorotic acid, and the phenotypes of the mutants were then examined. We analyzed cell growth and colony morphology properties by serial passaging on plates over several restreakings and telomere length by Southern blot analysis.

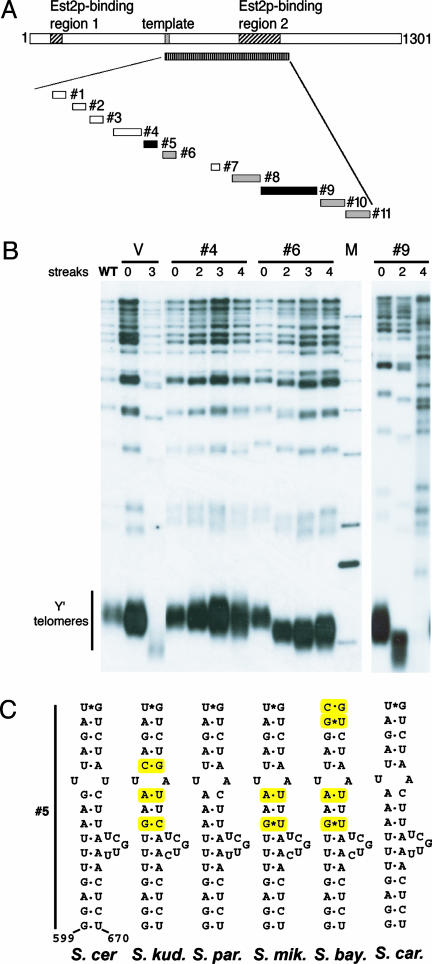

Fig. 1.

Deletional analysis of the central essential region of TLC1. (A) Diagram of TLC1 showing the deletions analyzed. The two previously reported Est2p-binding regions are marked (23). The central essential region is shown as a bar with straight lines. The deletions made in 11 mutants are shown underneath. Mutants with white bars have wild-type telomere length, mutants with gray bars have short telomeres, and mutants with black bars are senescent. (B) Southern blots with representative mutants. The V lanes are empty vector control. The numbers of streaks from which genomic DNA were prepared are indicated. Streak 0 is in the presence of the wild-type TLC1 plasmid. (C) Diagram showing the bulged-stem structure for Est1p binding. The solid line indicates the nucleotides deleted in mutant 4 in S. cerevisiae TLC1. The presumed Est1p-binding site in the TER RNAs of five other Saccharomyces species are shown. Yellow highlights show covariations that preserve base pairs.

The results enabled us to delineate the essential sequences in this central portion of TLC1 more precisely. Overall, the 5′ part of this region is not essential for function. Four mutants (#1 through #4), which in total delete ≈100 nt, had wild-type or close to wild-type telomere length (see Fig. 1 A and Table 1), indicating that nucleotides 495–598 are functionally dispensable. As the deletion scans extended toward the 3′ part of the central region, mutants gave rise to shorter, but still stably maintained telomeres, indicating that TLC1 function is compromised. An example of this class, #6, is shown in Fig. 1B. Strikingly, among the 11 deletional mutants, only two, #5 and #9, gave senescent phenotypes like that of a TLC1-null mutant (Fig. 1 A and B).

A conserved bulged-stem structure previously identified in seven budding yeast TERs is necessary for association of TLC1 with Est1p, a TER holoenzyme component, and various mutations within this bulged-stem structure cause senescence (18). Mutant 5 (Fig. 1 A and C) deletes one side of this stem and, as expected (18), caused a senescent phenotype (data not shown). The sequence and bulged-stem structure of this Est1p-binding element are also conserved in the TER RNAs of all six Saccharomyces species examined here (Fig. 1C).

The sequence deleted in the other senescent mutant, #9, lies within the larger previously defined Est2p-binding region (728–864) (23). The deletional mutants in the surrounding region were partially functional: #8, #10, and #11 had shorter telomeres but were not senescent (Table 1). Coimmunoprecipitation experiments using a myc-tagged Est2p showed that all three mutants #8, #9, and #10 had decreased Est2p-binding affinity (Table 1). In contrast, on a per TLC1 RNA molecule basis, mutant 11 bound to Est2p with the same efficiency as wild type, although the total steady-state RNA level was decreased (Table 1).

Identification of a Phylogenetically Conserved Pseudoknot Among Saccharomyces Species. We performed computational alignment using clustalx (24) and folding using alifold (25) of the nucleotide sequences of the single-copy TER RNA (TER) gene, identified by blast, in the genomes of the five Saccharomyces species from the sensu stricto group available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, S. bayanus, S. mikatae, and S. kudriavzevii) and of the full-length TER gene that we cloned and fully sequenced from S. kudriavzevii and S. cariocanus. We compared the resulting predicted structures with those of six Kluyveromyces yeast species described previously (15–17). Conserved primary nucleotide sequences CS1, CS3, and CS4 had been identified before only in the Kluyveromyces yeasts (Fig. 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In addition, putative pairing elements encompassing CS1, CS3, and CS4, as well as the conserved pseudoknot found previously in the Kluyveromyces yeasts (17) are conserved in both budding yeast groups (Fig. 2A and Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

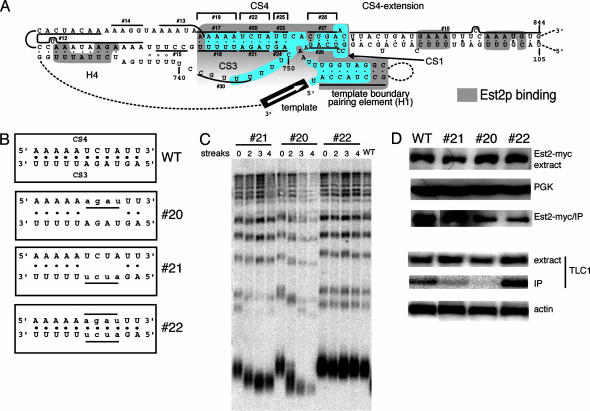

Fig. 2.

A compensatory mutant in the middle of CS3/CS4 pairing in S. cerevisiae completely restores telomere length and Est2p binding. (A) Diagram showing mutants tested in the CS1, CS3, and CS4 regions of S. cerevisiae TLC1. Mutation 16 was the combination of mutants 14 and 15. Compensatory mutants designed to restore predicted base pairings are #19, #17 and #18 combined; #22, #20 and #21 combined; #25, #23 and #24 combined; and #28, #26 and #27 combined. All mutations are substitutions to the complementary strand of the stem. Hence, they are all transversions except for #26, #27, and #28, which are transition mutants; and #10, #12, and #13, which are deletion mutants. Blue shading, bases conserved in Saccharomyces yeasts; gray shading, bases required for Est2p binding in vivo.(B) Diagram showing the mutations made in CS4 (#20), CS3 (#21), and the compensatory mutant (#22). (C) Telomere length is restored to wild type in CS3/CS4 compensatory mutant. The numbers of streaks from which genomic DNA were prepared are indicated. Streak 0 is in the presence of the wild-type TLC1 plasmid. (D) Est2p binding is reduced in CS3 and CS4 mutants but restored in the compensatory mutant. Cells containing the wild-type TLC1 plasmid, plus mutant #20–#22 plasmids, were transformed with pRS426Est2myc, a 2μ plasmid with 13myc at the C terminus of Est2p. Extracts were prepared as described in Methods, and the same amount of total protein for each strain, as determined by Bradford assay, was immunoprecipitated by anti-myc antibody. The extract and the immunoprecipitated samples were probed by anti-myc antibody on Western blots (extract and immunoprecipitated samples, respectively). The same blot was probed with anti-PGK antibody (Molecular Probes) for PGK as the loading control. RNA was prepared from the extracts and the immunoprecipitated samples and detected by [32P]dCTP-labeled probe against TLC1. Actin RNA served as the loading control. The amount of TLC1 in the immunoprecipitated lanes (IP) represents the Est2p-bound TLC1 level.

Helix 4 (H4; Fig. 2 A), described in the proposed core secondary structure of the Kluyveromyces species TERs (17), is conserved in all six Saccharomyces and corresponds to stem 1 of the conserved Kluyveromyces pseudoknot (17). Sequence covariation supports its existence in both yeast groups (17) (Fig. 5). CS3 and CS4 form loop 1 and stem 2 of the conserved pseudoknot (17). The template 5′ boundary helix [helix 1 in the Kluyveromyces species (16)] is also conserved and covariation supports its existence in the Saccharomyces species (Figs. 2 A and 5). Conserved sequence CS1 lies immediately 5′ of the conserved template-proximal pairing structure (helix 1 or H1) that delineates the 5′ boundary of the template in the Kluyveromyces spp. and S. cerevisiae TER RNAs (15, 16). In the new conserved secondary structure model, the 5′ part of CS1 is predicted to pair with the 3′ part of CS4, referred to as “CS4-extension” (Figs. 2 A and 5). This pairing brings the pseudoknot close to the templating domain in the TER RNA structure of all these budding yeasts.

During the preparation of this manuscript (20) and while it was under review for publication (21), two groups reported phylogenetic analysis of TERs from Saccharomyces yeasts and predicted their secondary structures. The predicted structures we independently identified (Fig. 2 A and 5) are in agreement with those reports.

Mutational Analysis of the Putative Pseudoknot Structure in S. cerevisiae TER RNA TLC1. Substitution mutations, numbers 12–30, designed to disrupt the predicted pairings shown in Fig. 2 A, and the corresponding compensatory mutations designed to restore their base-pairing capability were tested (Table 1 and Fig. 2 A). Each mutant was analyzed as described above for the scanning deletion mutations. We also analyzed total cellular levels of each mutant TLC1 RNA and its ability to be coimmunoprecipitated with myc-tagged Est2p protein, as a measure of its association with Est2p in vivo. The results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Representative results are shown for one set of mutants in Fig. 2 B–D (discussed below).

Deletion of either side of predicted helix 4 in S. cerevisiae TLC1 (mutants 12, 13, and 170) or changing the sequences surrounding helix 4 (mutants 14, 15, and 16) only modestly decreased telomere length or cell growth (Fig. 2 and Tables 1 and 2). In contrast, substitution mutations in the conserved primary sequences within predicted stem 2 of the pseudoknot (mutants 17 and 18) dramatically shortened the telomeres (Fig. 2C and Table 1), and restoration of stem 2 pairing in the compensatory mutant 19 did not restore telomere length. The steady-state TLC1 RNA levels were not significantly lower than wild type in these three mutants. Notably, Est2p association in vivo was reduced in mutants 18 (63%) and 19 (35%) and reduced even more in mutant 17 (19%). These findings indicate that the two highly conserved primary sequences (5′-AAAAA-3′/3′-UUUUU-5′) in the predicted pseudoknot stem 2 (Fig. 3) are important for TER function in S. cerevisiae, as they are in the Kluyveromyces lactis TER RNA (17).

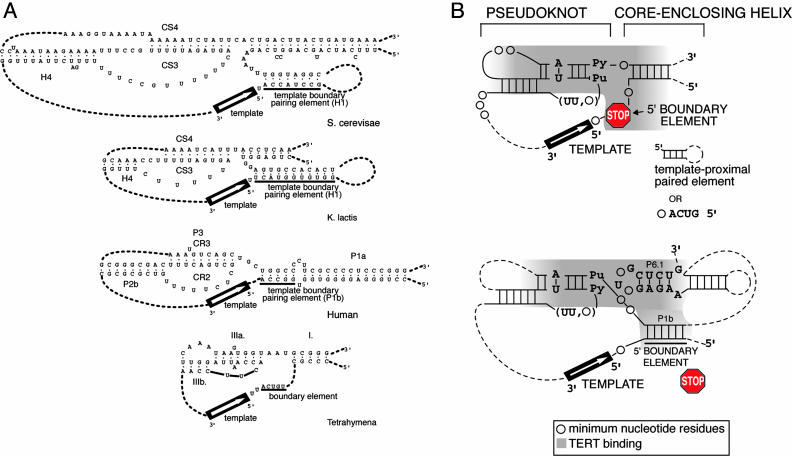

Fig. 3.

Proposed unified model for the common secondary structure core for TER RNA. (A) Comparison of the common core and TERT-binding regions in representative species of eukaryotes: the budding yeasts S. cerevisiae, K. lactis, human (vertebrate), and Tetrahymena thermophila (ciliate) TER RNAs. (B) Proposed unified model for the common secondary structure core for all TER RNAs. The model (see text) is based on data from the present article combined with published data from ciliates, mammals, and yeasts (Kluyveromyces and Saccharomyces groups). Nucleotides or structures important for binding of TERT (Est2p in S. cerevisiae) are indicated by gray shading. The barrier function of the TER RNA is achieved in different ways in different phylogenetic groups (Upper). In the budding yeasts only the secondary structure of the 5′ boundary element (helix 1) is important, with no requirement for a given sequence. Helix 1 begins one to four TER RNA residues upstream from the last nucleotide of the maximal putative template (15, 16). In contrast, in ciliate TERs, the 5′ boundary element is a conserved primary sequence ACUG 5′, located two residues upstream from the last template residue copied (26) (Lower). In vertebrate TERs, the P1b helix provides template 5′ boundary function (32). Like the yeast helix 1, the barrier function of vertebrate P1b helix requires only its paired structure, but not its sequence, and the P1b helix can be located four or more residues upstream of the 5′ boundary of the template used in vitro. However, in mouse, rat, and hamster TER RNAs, the 5′ end of the whole TER molecule is only 2 bases up from the 5′ boundary of the templating domain. Thus, it has been surmised that run-off copying occurs in those species, and then the extra bases are trimmed off by the inherent endonuclease activity of the TER ribonucleoprotein (32, 38, 39).

Mutations 20 and 21, four-base substitutions that disrupt the central region of predicted stem 2 (see Fig. 2 A), caused large reductions in both Est2p binding and telomere length in vivo (Fig. 2 C and D), whereas restoration of stem 2 pairing (mutant 22) largely restored Est2p binding (to 69%) and fully restored telomere length to wild type (Fig. 2 C and D). The two-base substitution mutations 23 and 24 disrupt one end of stem 2 (Fig. 2 A); each decreased Est2p binding to ≈40% of wild type (Table 1), whereas restoration of base pairing (compensatory mutant 25) partially restored the Est2p binding (to 71%), but not telomere length (Table 1). Mutating the conserved U-rich sequence in loop 1, which is part of conserved sequence CS3, caused major telomere shortening (mutant 30; Table 1).

These results showed that the paired structure and the primary sequence of stem 2 (composed of CS3 and CS4) are important for Est2p binding and TER function. Although stem 1 of the pseudoknot was apparently dispensable in our experiments, its existence is supported by its phylogenetic covariation in both Kluyveromyces and Saccharomyces yeasts (17). Taken together, these results, the structural conservation of stem 1 across all eukaryotes, and the mutagenic evidence for the functional importance of this stem 1 in mammalian and Tetrahymena TERs (10, 12), support the existence of a conserved pseudoknot.

Covariation indicates a long-range pairing between CS1, CS4, and their extensions (ref. 16 and Fig. 5). Such a pairing would bring the pseudoknot and the 5′ boundary element into close proximity both to each other and to the template. We therefore mutated the pseudoknot-proximal four bases of this putatively paired region, either to disrupt the pairing (mutants 26 and 27) or restore it (compensatory mutant 28). In mutant 26 the RNA level was <1% of wild type, so that binding to Est2p could not be measured, and cells underwent telomere shortening and senescence similar to TER-null S. cerevisiae (data not shown). Mutant 27 had moderately reduced telomere length, and reduced Est2p binding (≈40% of wild type). Combining these two substitution mutations in mutant 28 restored telomere length to near wild-type and RNA levels to fully wild-type level, although Est2p binding remained at ≈40% of wild type. Finally, a substitution mutant with separate alterations in two stretches on both sides of the CS1/CS4-ext paired region (Table 1, mutant 29) had a minor telomere shortening, suggesting that the primary sequence and pairing of this part of the CS4 extension are partially dispensable for TER action (Table 1).

Discussion

By experimentally delineating bases and structures important for S. cerevisiae TER RNA (TLC1) binding to Est2p, and for TER function in vivo, we provide previously unreported information on a specific and conserved Est2p/TERT-TLC1/TER interaction domain of TER RNA, and insight into how it is positioned relative to the template and the template boundary element. This TERT–TER interaction region falls within a common core secondary structure of TER for budding yeast TER RNAs, which is similar to that previously proposed for the ciliate and vertebrate TER RNAs (Fig. 3A).

TER RNA Elements Required for TERT Binding. We identified a minimal set of nucleotides and structures needed for yeast TER RNA to bind TERT (Est2p in yeast). Base pairing of the central region of stem 2 of the conserved pseudoknot, and the conserved primary sequence (5′-AAAAA-3′/3′-UUUUU-5′) flanking this central part of stem 2, are both important for in vivo Est2p binding and telomere maintenance (Table 1 and Fig. 2, mutants 17–25). This stem 2 sequence is conserved between Saccharomyces and Kluyveromyces yeasts, and similar results were obtained in both yeasts. Whereas stem 1 mutations in S. cerevisiae caused only minor effects on telomere length and Est2p binding, mutation of the equivalent stem 1 of the pseudoknot in Tetrahymena TER largely abrogates TER enzyme activity and in vivo function, and these pseudoknot mutant RNAs also lose stable association with Tetrahymena TERT protein (10). Another region, a specific CC sequence at positions 15 and 16 in Tetrahymena TER RNA (26) is also required for binding to TERT. The human TERT also requires the pseudoknot domain for binding, although it has not been possible to delineate precisely the necessary bases within this domain (11, 12).

We conclude that, for stable in vivo binding of TERT to TER RNA, the pseudoknot structure is universally important and that in yeasts the CS3/CS4-paired structure and its sequence are particularly critical. The vertebrate TER RNA has a highly conserved separate region that can bind independently to TERT; a critical part of this domain is a specific essential sequence that forms a short stem-loop structure, the P6.1 helix (27). We therefore suggest that the vertebrate TER RNAs and the ciliate and yeast RNAs share a common feature of two (possibly coaxial and stacked) helices, which together normally mediate TERT binding. The first helix is stem 2 of the pseudoknot. The other is the core-enclosing helix in ciliate and yeast TER RNAs (Fig. 3B Upper), and helix P6.1 in vertebrate TER RNAs (Fig. 3B Lower). The 5′ boundary element, which also interacts with TERT, is then positioned in a common location nearby, as shown in Fig. 3B.

A Universal Core Secondary Structure for TER RNAs. Taking into account all the known sequences of eukaryotic TER RNAs (from 12 budding yeast, 35 vertebrate, and >30 ciliate species), we propose a minimal conserved core secondary structure, as shown in Fig. 3B. Historically, various names have been given to the different structural and sequence elements of the conserved core secondary structure of TER RNAs in various eukaryotic groups. We therefore propose a unifying nomenclature for the four functional elements conserved in eukaryotic TER RNA: (A) the templating domain; (B) the 5′ boundary element; (C) the pseudoknot which, together with a second helix, binds TERT; (D) a long-range pairing (core-enclosing helix) that encloses the template and pseudoknot. Substructures within these four elements are summarized in Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. These common core features have persisted across the wide phylogenetic diversity represented by ciliates, vertebrates, and fungi (yeasts).

In the templating domain (core element A), particular bases can strongly affect enzyme active-site functions/enzymatic properties, as demonstrated by base mutations in the template sequence (22, 28–31). These findings have suggested that specific interactions exist between TERT functional groups and TER template residues.

The template 5′ boundary-defining structure in TER RNAs (core element B) differs among phylogenetic groups. In yeast and mammalian TERs its barrier function requires only a helical structure (15, 16, 32), but a specific primary sequence is required in ciliate TERs (9). In all known cases, the 5′ boundary element is also required for high-affinity TERT protein binding, as shown for the ACUG sequence in Tetrahymena TER (26), the S. cerevisiae helix 1 (15), and the human P1b helix (32–34).

The conserved pseudoknot in the TER core structure (core element C) has been identified and tested in ciliate, vertebrate, and K. lactis TER RNAs (5, 8, 10, 12 17, 35). The new phylogenetic studies and experimental, mutational analyses reported here provide evidence that the budding yeast pseudoknot is the functional equivalent of the one in ciliates and vertebrates. Human TER RNA can form a structure called a “trans” pseudoknot, in which interaction between two TER RNAs involves an intermolecular pairing version of stem 2 (13). Whether such a “transpseudoknot” extends to all TER RNAs is unknown. However, it is notable in this regard that S. cerevisiae TER has been shown to be dimeric, with functionally interacting RNAs and TERTs (30, 36). Finally, the core-enclosing helix (core element D) partitions off the pseudoknot and the template from the rest of the TER.

For stem 1 of the pseudoknot and the core-enclosing helix, only the secondary structure is universally conserved. In contrast, some primary sequence conservation persists in pseudoknot stem 2, and U-richness of loop 1 is also conserved across all eukaryotes. Both these sequences are important for Est2p binding. Within a given phylogenetic group, further conservation of the TERT interaction domain sequences also occurs, most notably of CS3/CS4 among the yeasts and of CR2, CR3, and CR4/5 (including helix P6.1) among vertebrates.

The minimal core secondary structure falls into two classes (Fig. 3B). In yeasts and ciliates, the high-affinity TERT-binding site includes the pseudoknot and the immediately covalently linked core-enclosing helix (core element D). However, in the vertebrate TER RNAs, where this helix (P1b) is present [>80% of the species analyzed (5)], it is the 5′ boundary element (32). In the vertebrate TERs, the high-affinity TERT-binding site instead includes the pseudoknot domain and helix P6.1 (27). This short helix is far away in the primary sequence from stem 2 of the pseudoknot, but we propose that in vertebrate TERs it is brought spatially close to the template, as shown schematically in Fig. 3B. The interactions bringing vertebrate P6.1 near the pseudoknot stem 2 and template are unknown in the ribonucleoprotein complex but possibly involve RNA–RNA long-range interactions (37).

The conservation of the TER RNA core suggests that it is an ancient structure that has been under continuous positive selection through much of eukaryotic evolution. Our model predicts a close apposition of the highly specific TERT-binding site in the pseudoknot domain with the template and template 5′ boundary element. This prediction highlights the potential for interaction between template residues and TERT. This work will help guide further investigations of how the functional groups of RNA and protein interact structurally and dynamically with each other to accomplish accurate and efficient assembly, and the enzymatic functions, of TER.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Herbert W. Boyer Fund postdoctoral fellowship (to J.L.), a Leukemia-Lymphoma Society of America Special fellowship, a University of California, San Francisco, AIDS Training Grant, and an American Cancer Society–Emory Cancer Institute grant (to H.L.), United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation Grant 2001065 (to Y.T.), and National Institutes of Health Grants AI40317 (to T.G.P.) and GM26259 (to E.H.B.).

Abbreviations: TER, telomerase; TERT, TER reverse transcriptase.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database [accession nos. Ay737251 (the telomerase RNA gene of Saccharomyces cariocanus) and AY737252 (the telomerase RNA gene of Saccharomyces kudriavzevii)].

See Commentary on page 14683.

References

- 1.Nakamura, T. M., Morin, G. B., Chapman, K. B., Weinrich, S. L., Andrews, W. H., Lingner, J., Harley, C. B. & Cech, T. R. (1997) Science 277, 955–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Counter, C. M., Meyerson, M., Eaton, E. N. & Weinberg, R. A. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 9202–9207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greider, C. W. & Blackburn, E. H. (1989) Nature 337, 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackburn, E. H. (2000) Keio. J. Med. 49, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, J. L., Blasco, M. A. & Greider, C. W. (2000) Cell 100, 503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya, A. & Blackburn, E. H. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 5721–5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero, D. P. & Blackburn, E. H. (1991) Cell 67, 343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Autexier, C., Triki, I. & Greider, C. W. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 2227–2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Autexier, C. & Greider, C. W. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilley, D. & Blackburn, E. H. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6621–6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell, J. R. & Collins, K. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ly, H., Blackburn, E. H. & Parslow, T. G. (2003) Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 6849–6856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ly, H., Xu, L., Rivera, M. A., Parslow, T. G. & Blackburn, E. H. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1078–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachand, F. & Autexier, C. (2001) Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 1888–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seto, A. G., Umansky, K., Tzfati, Y., Zaug, A. J., Blackburn, E. H. & Cech, T. R. (2003) RNA 9, 1323–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzfati, Y., Fulton, T. B., Roy, J. & Blackburn, E. H. (2000) Science 288, 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzfati, Y., Knight, Z., Roy, J. & Blackburn, E. H. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1779–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seto, A. G., Livengood, A. J., Tzfati, Y., Blackburn, E. H. & Cech, T. R. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2800–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seto, A. G., Zaug, A. J., Sobel, S. G., Wolin, S. L. & Cech, T. R. (1999) Nature 401, 177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dandjinou, A. T., Levesque, N., Larose, S., Lucier, J. F., Abou Elela, S. & Wellinger, R. J. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 1148–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zappulla, D. C. & Cech, T. R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10024–10029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prescott, J. & Blackburn, E. H. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 528–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livengood, A. J., Zaug, A. J. & Cech, T. R. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 2366–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F. & Higgins, D. G. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofacker, I. L., Fekete, M. & Stadler, P. F. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 319, 1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai, C. K., Miller, M. C. & Collins, K. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen, J. L., Opperman, K. K. & Greider, C. W. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 592–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilley, D., Lee, M. S. & Blackburn, E. H. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 2214–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilley, D. & Blackburn, E. H. (1996) Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prescott, J. & Blackburn, E. H. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 2790–2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, J, Smith, D. L. & Blackburn, E. H. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1623–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen, J. L. & Greider, C. W. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 2747–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beattie, T. L., Zhou, W., Robinson, M. O. & Harrington, L. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tesmer, V. M., Ford, L. P., Holt, S. E., Frank, B. C., Yi, X., Aisner, D. L., Ouellette, M., Shay, J. W. & Wright, W. E. (1999) Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 6207–6216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ten Dam, E., van Belkum, A. & Pleij, K. (1991) Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin, J. & Blackburn, E. H. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 387–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueda, C. T. & Roberts, R. W. (2004) RNA 10, 139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen, J. L. & Greider, C. W. (2003b) EMBO J. 22, 304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinkley, C. S., Blasco, M. A., Funk, W. D., Feng, J., Villeponteau, B., Greider, C. W. & Herr, W. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 532–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.