Abstract

The genus Calonectria with its Cylindrocladium asexual morphs has been subject to several taxonomic revisions in the past. These have resulted in the recognition of 116 species, of which all but two species (C. hederae and C. pyrochroa) are supported by ex-type cultures and supplemented with DNA barcodes. The present study is based on a large collection of unidentified Calonectria isolates that have been collected over a period of 20 years from various substrates worldwide, which has remained unstudied in the basement of the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre. Employing a polyphasic approach, the identities of these isolates were resolved and shown to represent many new phylogenetic species. Of these, 24 are newly described, while C. uniseptata is reinstated at species level. We now recognise 141 species that include some of the most important plant pathogens globally.

Key words: Cylindrocladium, Cryptic species, Phylogeny, Taxonomy

Taxonomic novelties: New species: Calonectria amazonica L. Lombard & Crous, C. amazoniensis L. Lombard & Crous, C. brasiliana L. Lombard & Crous, C. brassicicola L. Lombard & Crous, C. brevistipitata L. Lombard & Crous, C. cliffordiicola L. Lombard & Crous, C. ericae L. Lombard & Crous, C. indonesiana L. Lombard & Crous, C. lageniformis L. Lombard & Crous, C. machaerinae L. Lombard & Crous, C. multilateralis L. Lombard & Crous, C. paracolhounii L. Lombard & Crous, C. parva L. Lombard & Crous, C. plurilateralis L. Lombard & Crous, C. pseudoecuadoriae L. Lombard & Crous, C. pseudouxmalensis L. Lombard & Crous, C. putriramosa L. Lombard & Crous, C. stipitata L. Lombard & Crous, C. syzygiicola L. Lombard & Crous, C. tereticornis L. Lombard & Crous, C. terricola L. Lombard & Crous, C. tropicalis L. Lombard & Crous, C. uxmalensis L. Lombard & Crous, C. venezuelana L. Lombard Crous

Introduction

The genus Calonectria, first introduced in 1867 (Rossman 1979), has been the subject of numerous taxonomic studies since the 1990s (Crous & Wingfield 1994, Crous, 2002, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2015a, Alfenas et al., 2015). These studies have resulted in the recognition of 116 species, of which all but two (C. hederae and C. pyrochroa) are supported by ex-type cultures and supplemented by DNA barcodes (Crous, 2002, Lechat et al., 2010, Lombard et al., 2010b). This large number of species has arisen mainly due to the introduction of DNA sequence data and subsequent phylogenetic inference enabling delimitation of numerous previously unrecognised cryptic taxa. These species often share the same plant hosts, informing knowledge of the epidemiology and fungicide resistance (Graça et al., 2009, Vitale et al., 2013, Gehesquière et al., 2016).

Calonectria spp. are characterised by sexual morphs that have yellow to dark red perithecia, with scaly to warty ascocarp walls, and Cylindrocladium asexual morphs in which the cylindrical and septate conidia are produced from phialides clustered below and surrounding a stipe extention terminating in variously shaped vesicles (Rossman, 1993, Crous, 2002, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2010c). For many years these fungi were best known by their Cylindrocladium names associated with important plant diseases (Crous and Wingfield, 1994, Crous, 2002, Lombard et al., 2010c). Following convention that only one scientific name should be used for a fungal species (Hawksworth, 2011, Hawksworth, 2012, Hawksworth et al., 2011, McNeill et al., 2012), Calonectria has been chosen (Rossman et al. 2013). This newly adopted convention should resolve confusion regarding their names (Wingfield et al. 2011). However, it is important to recognise that the asexual Cylindrocladium morph represents the life phase most commonly found in nature and many species are known only in this form, which also plays a major role in the dissemination of Calonectria spp.

Calonectria spp. cause important diseases in numerous plant hosts worldwide. This includes leaf blight, cutting rot, damping-off and root rot (Crous, 2002, Lombard et al., 2010c, Lombard et al., 2015a, Vitale et al., 2013, Alfenas et al., 2015). The majority of the diseases caused by Calonectria spp. are associated with forestry-related plants (see Lombard et al. 2010c), where Calonectria leaf blight (CLB) is an important constraint to plantation productivity in South America (Rodas et al., 2005, Alfenas et al., 2015) and Southeast Asia (Crous and Kang, 2001, Old et al., 2003, Chen et al., 2011, Lombard et al., 2015a). In other regions, such as southern Africa and Australia, Calonectria spp. appear mostly to be limited to forestry nurseries (Crous, 2002, Lombard et al., 2009, Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2010c). In agricultural and horticultural crops, Calonectria spp. have chiefly been reported only from South America and the Northern Hemisphere, where they are mostly associated with nursery diseases (Lombard et al., 2010c, Vitale et al., 2013), Cylindrocladium black rot of peanut (Bell and Sobers, 1966, Beute and Rowe, 1973, Hollowell et al., 1998) and box blight of Buxus spp. (Henricot et al., 2000, Crepel and Inghelbrecht, 2003, Brand, 2005, Saracchi et al., 2008, Saurat et al., 2012, Mirabolfathy et al., 2013, Gehesquière et al., 2016).

The present study is based on a large collection of unidentified Calonectria isolates that were collected over a period of 20 years from various substrates worldwide. This collection of isolates, deposited in the CBS-KNAW culture collection in 2002 has remained unstudied in the basement of the institute and hence, the title of this study “the forgotten basement collection”. The large majority of these isolates were initially identified based solely on morphology and at a time when robust and multigene DNA sequence data were not commonly available. This implied that cryptic species could not be resolved (Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2015a, Alfenas et al., 2015). The aim of the present study was to employ a polyphasic approach to identify these isolates.

Materials and methods

Isolates

Calonectria strains were obtained from the culture collection of the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands and the working collection of the senior author (CPC) housed at the CBS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Calonectria spp. used in phylogenetic analyses.

| Species | Isolate nr.1 | Substrate | Locality | GenBank accession no.2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tub2 | cmdA | tef1 | ||||

| Calonectria acicola | CBS 114812 | Phoenix canariensis | New Zealand | DQ190590 | GQ267359 | GQ267291 |

| CBS 114813 | P. canariensis | New Zealand | DQ190591 | GQ267360 | GQ267292 | |

| C. aconidialis | CBS 136086; CMW 35174; CERC 1850 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Hainan, China | – | KJ463017 | KJ462785 |

| CBS 136091; CMW 35384; CERC1886 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Hainan, China | – | – | KJ462786 | |

| C. amazonica | CBS 115486; CPC 3894 | E. tereticornis | Brazil | KX784611 | KX784554 | KX784681 |

| CBS 116250; CPC 3534 | E. tereticornis | Brazil | KX784612 | KX784555 | KX784682 | |

| C. amazoniensis | CBS 115438; CPC 3890 | E. tereticornis | Brazil | KX784613 | KX784556 | KX784683 |

| CBS 115439; CPC 3889 | E. tereticornis | Brazil | KX784614 | KX784557 | KX784684 | |

| CBS 115440; CPC 3885 | E. tereticornis | Brazil | KX784615 | KX784558 | KX784685 | |

| C. angustata | CBS 109065; CPC 2347 | Tillandsia capitata | USA | AF207543 | GQ267361 | FJ918551 |

| CBS 112133; CPC 3152 | T. capitata | USA | DQ190593 | GQ267362 | FJ918552 | |

| C. arbusta | CBS 136079; CMW 31370; CERC1705 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | KJ462904 | KJ463018 | KJ462787 |

| CBS 136098; CPC 23519; CMW37981; CERC 1944 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | – | KJ463019 | KJ462788 | |

| C. asiatica | CBS 112711; CPC 3898 | Leaf litter | Thailand | AY725613 | AY725738 | AY725702 |

| CBS 114073; CPC 3900 | Leaf litter | Thailand | AY725616 | AY725741 | AY725705 | |

| C. australiensis | CBS 112954 | Ficus pleurocarpa | Australia | DQ190596 | GQ267363 | GQ267293 |

| C. blephiliae | CBS 136425; CPC 21859 | Blephilia cliata | USA | KF777246 | – | KF777243 |

| C. brachiatica | CBS 123700; CMW 25298 | Pinus maximinoi | Buga, Colombia | FJ696388 | GQ267366 | GQ267296 |

| CBS134665; LPF305 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Monte Dourado, Pará, Brazil | KM395933 | KM396020 | KM395846 | |

| C. brasiliana | CBS 111484; CPC 1924 | Soil | Brazil | KX784616 | KX784559 | KX784686 |

| CBS 111485; CPC 1929 | Soil | Brazil | KX784617 | KX784560 | KX784687 | |

| C. brasiliensis | CBS 230.51; CPC 2390 | Anacardium sp. | Brazil | GQ267241 | GQ267421 | GQ267328 |

| CBS 114257; CPC 1944 | Eucalyptus leaf | Brazil | GQ267242 | GQ267422 | GQ267329 | |

| C. brassiana | CBS 134855 | Soil | Teresina, Piauí, Brazil | KM395969 | KM396056 | KM395882 |

| CBS 134856 | Soil | Teresina, Piauí, Brazil | KM395970 | KM396057 | KM395883 | |

| C. brassicae | CBS 111478; CPC 1921 | Soil | Brazil | DQ190611 | GQ267383 | FJ918568 |

| CBS 111869; CPC 2409 | Argyeia splendens | Indonesia | AF232857 | GQ267382 | FJ918567 | |

| C. brassicicola | CBS 112756; CPC 4502 | Brassica sp. | Indonesia | KX784618 | – | KX784688 |

| CBS 112841; CPC 4552 | Brassica sp. | Indonesia | KX784619 | KX784561 | KX784689 | |

| CBS 112947; CPC 4668 | New Zealand | KX784620 | KX784562 | KX784690 | ||

| C. brevistipitata | CBS 110837; CPC 913 | Soil | Mexico | KX784621 | KX784563 | KX784691 |

| CBS 110928; CPC 951 | Soil | Mexico | KX784622 | KX784564 | KX784692 | |

| CBS 115671; CPC 949 | Soil | Mexico | KX784623 | KX784565 | KX784693 | |

| C. canadania | CBS 110817; CPC 499 | Canada | AF348212 | AY725743 | GQ267297 | |

| C. candelabrum | CPC 1675 | Eucalyptus sp. | Amazonas, Brazil | FJ972426 | GQ267367 | FJ972525 |

| CMW 31001 | Eucalyptus sp. | Amazonas, Brazil | GQ421779 | GQ267368 | GQ267298 | |

| C. cerciana | CBS 123693; CMW 25309 | Eucalyptus cutting | Zhanjiang, China | FJ918510 | GQ267369 | FJ918559 |

| CBS 123695; CMW 25290 | Eucalyptus cutting | Zhanjiang, China | FJ918511 | GQ267370 | FJ918560 | |

| C. chinensis | CBS 112744; CPC 4104 | Soil | Hong Kong, China | AY725618 | AY725746 | AY725709 |

| CBS 114827; CPC 4101 | Soil | Hong Kong, China | AY725619 | AY725747 | AY725710 | |

| C. clavata | CBS 114557; ATCC 66389; CPC 2536 | Callistemon viminalis | USA | AF333396 | GQ267377 | GQ267305 |

| CBS 114666; CMW 30994; CPC 2537 | Root debris in peat | USA | DQ190549 | GQ267378 | GQ267306 | |

| C. cliffordiicola | CBS 111812; CPC 2631 | Cliffordia feruginea | South Africa | KX784624 | KX784566 | KX784694 |

| CBS 111814; CPC 2617 | Prunus avium | South Africa | KX784625 | KX784567 | KX784695 | |

| CBS 111819; CPC 2604 | P. avium | South Africa | KX784626 | KX784568 | KX784696 | |

| C. colhounii | CBS 293.79 | Camellia sinensis | Bandung, Indonesia | DQ190564 | GQ267373 | GQ267301 |

| CBS 114704 | Arachis pintoi | Australia | DQ190563 | GQ267372 | GQ267300 | |

| Ca. colombiana | CBS 115127; CPC 1160 | Soil | La Selva, Colombia | FJ972423 | GQ267455 | FJ972492 |

| CBS 115638; CPC 1161 | Soil | La Selva, Colombia | FJ972422 | GQ267456 | FJ972491 | |

| C. colombiensis | CBS 112220; CPC 723 | Soil | La Selva, Colombia | GQ267207 | AY725748 | AY725711 |

| CBS 112221; CPC 724 | Eucalyptus grandis | La Selva, Colombia | AY725620 | AY725749 | AY725712 | |

| C. crousiana | CBS 127198; CMW 27249 | E. grandis | Fujian, China | HQ285794 | – | HQ285822 |

| CBS 127199; CMW 27253 | E. grandis | Fujian, China | HQ285795 | – | HQ285823 | |

| C. cylindrospora | CBS 110666; CPC 496 | USA | FJ918509 | GQ267423 | FJ918557 | |

| CBS 119670; CPC 12766 | Pistacia lentiscus | Italy | DQ521600 | – | GQ421797 | |

| C. densa | CBS 125249; CMW 31184 | Soil | Las Golondrinas, Pichincha, Ecuador | GQ267230 | GQ267442 | GQ267350 |

| CBS 125261; CMW 31182 | Soil | Las Golondrinas, Pichincha, Ecuador | GQ267232 | GQ267444 | GQ267352 | |

| C. duoramosa | CBS 134656; LPF434 | Soil | Monte Dourado, Pará, Brazil | KM395940 | KM396027 | KM395853 |

| LPF453 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Monte Dourado, Pará, Brazil | KM395941 | KM396028 | KM395854 | |

| C. ecuadoriae | CBS 111406; CPC 1635 | Soil | Ecuador | DQ190600 | GQ267375 | GQ267303 |

| CBS 111394; CPC 1628 | Soil | Ecuador | DQ190599 | GQ267376 | GQ267304 | |

| C. ericae | CBS 114456; CPC 1984 | Erica sp. | USA | KX784627 | KX784569 | KX784697 |

| CBS 114457; CPC 1985 | Erica sp. | USA | KX784628 | KX784570 | KX784698 | |

| CBS 114458; CPC 2019 | Erica sp. | USA | KX784629 | KX784571 | KX784699 | |

| C. eucalypti | CBS 125273; CMW 14890 | E. grandis | Indonesia | GQ267217 | GQ267429 | GQ267337 |

| CBS 125275; CMW 18444 | E. grandis | Indonesia | GQ267218 | GQ267430 | GQ267338 | |

| C. eucalypticola | CBS 134846 | Eucalyptus leaf | Eunápolis, Bahia, Brazil | KM395963 | KM396050 | KM395876 |

| CBS 134847 | Eucalyptus seedling | Santa Bárbara, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395964 | KM396051 | KM395877 | |

| C. expansa | CBS 136078; CMW 31441; CERC 1776 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangdong, China | KJ462913 | KJ463028 | KJ462797 |

| CBS 136247; CMW 31392; CERC 1727 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | KJ462914 | KJ463029 | KJ462798 | |

| C. foliicola | CBS 136641; CMW 31393; CERC 1728 | E. urophylla × E. grandis clone leaf | Guangxi, China | KJ462916 | KJ463031 | KJ462800 |

| CMW 31394; CERC 1729 | E. urophylla × E. grandis clone leaf | Guangxi, China | KJ462917 | KJ463032 | KJ462801 | |

| C. fujianensis | CBS 127200; CMW 27254 | E. grandis | Fujian, China | HQ285791 | – | HQ285819 |

| CBS 127201; CMW 27257 | E. grandis | Fujian, China | HQ285792 | – | HQ285820 | |

| C. glaeboicola | CBS 134852 | Soil | Martinho Campos, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395966 | KM396053 | KM395879 |

| CBS 134853 | Soil | Bico do Papagaio, Tocantins, Brazil | KM395967 | KM396054 | KM395880 | |

| C. gordoniae | CBS 112142; CPC 3136; ATCC 201837 | Gordonia liasanthus | USA | AF449449 | GQ267381 | GQ267309 |

| C. gracilipes | CBS 111141 | Soil | La Selva, Colombia | DQ190566 | GQ267385 | GQ267311 |

| CBS 115674 | Soil | La Selva, Colombia | AF333406 | GQ267384 | GQ267310 | |

| C. gracilis | CBS 111284 | Soil | Brazil | DQ190567 | GQ267408 | GQ267324 |

| CBS 111807 | Manilkara zapota | Belém, Pará, Brazil | AF232858 | GQ267407 | GQ267323 | |

| C. guangxiensis | CBS 136092; CMW 35409; CERC 1900 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | KJ462919 | KJ463034 | KJ462803 |

| CBS 136094; CMW 35411; CERC 1902 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | KJ462920 | KJ463035 | KJ462804 | |

| C. hainanensis | CBS 136248; CMW 35187; CERC 1863 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Hainan, China | – | KJ463036 | KJ462805 |

| C. hawksworthii | CBS 111870; CPC 2405; MUCL 30866 | Nelumbo nucifera | Mauritius | AF333407 | GQ267386 | FJ918558 |

| C. henricotiae | CB041 | Buxus sempervirens | Belgium | KF815129 | KF815156 | – |

| CBS 138102; CB045 | B. sempervirens | Belgium | JX535308 | KF815157 | – | |

| C. hodgesii | CBS 133609; LPF 245 | Anadenanthera peregrina | Viçosa, Brazil | KC491228 | KC491222 | KC491225 |

| CBS 133610; LPF 261 | Azadirachta indica | Viçosa, Brazil | KC491229 | KC491223 | KC491226 | |

| C. hongkongensis | CBS 114711; CPC 686 | Soil | Hong Kong, China | AY725621 | AY725754 | AY725716 |

| CBS 114828; CPC 4670 | Soil | Hong Kong, China | AY725622 | AY725755 | AY725717 | |

| C. humicola | CBS 125251 | Soil | Las Golondrinas, Pichincha, Ecuador | GQ267233 | GQ267445 | GQ267353 |

| CBS 125269 | Soil | Las Golondrinas, Pichincha, Ecuador | GQ267235 | GQ267447 | GQ267355 | |

| C. hurae | CBS 114182; CPC 1714 | Rumohra adiantiformis | Brazil | DQ190618 | – | – |

| CBS 114551; CPC 2344 | R. adiantiformis | USA | AF333408 | GQ267387 | FJ918548 | |

| C. ilicicola | CBS 190.50; CMW 30998; IMI 299389 | Solanum tuberosum | Bogor, Indonesia | AY725631 | AY725764 | AY725726 |

| CBS 115897; CPC 493; UFV 108 | Anacardium sp. | Brazil | AY725647 | GQ267403 | AY725729 | |

| C. indonesiae | CBS 112823; CPC 4508 | Soil | Warambunga, Indonesia | AY725623 | AY725756 | AY725718 |

| CBS 112840; CPC 4554 | Syzygium aromaticum | Indonesia | AY725625 | AY725758 | AY725720 | |

| C. indonesiana | CBS 112826; CPC 4519 | Indonesia | KX784630 | KX784572 | KX784700 | |

| CBS 112936; CPC 4504 | Indonesia | KX784631 | KX784573 | KX784701 | ||

| C. indusiata | CBS 144.36 | Camellia sinensis | Sri lanka | GQ267239 | GQ267453 | GQ267332 |

| CBS 114684 | Rhododendron sp. | USA | AF232862 | GQ267454 | GQ267333 | |

| C. insularis | CBS 114558; CPC 768 | Soil | Tamatave, Madagascar | AF210861 | GQ267389 | FJ918556 |

| CBS 114559; CPC 954 | Soil | Tamatave, Madagascar | AF210862 | GQ267390 | FJ918555 | |

| C. kyotensis | CBS 114525; CPC 2367; ATCC 18834 | Acacia dealbata | Japan | |||

| CBS 114542; CPC 2352 | Soil | China | KX784649 | – | KX784720 | |

| CBS 114550; CPC 2351 | Soil | China | KX784650 | KX784587 | KX784721 | |

| CBS 114692; CPC 2478; ATCC 18882 | Prunus sp. | USA | KX784651 | KX784588 | KX784722 | |

| C. lageniformis | CBS 111324; CPC 1473 | Eucalyptus sp. | Mauritius | KX784632 | KX784574 | KX784702 |

| CBS 112685; CPC 3418 | Eucalyptus sp. | Brazil | KX784633 | KX784575 | KX784703 | |

| C. lateralis | CBS 136629; CMW 31412; CERC 1747 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Fangchenggang, Guangxi, China | KJ462955 | KJ463070 | KJ462840 |

| C. lauri | CBS 749.70 | Ilex aquifolium | Netherlands | GQ267210 | GQ267388 | GQ267312 |

| C. leucothoes | CBS 109166; CPC 2385; ATCC 64824 | Leucothoe axillaris | Gainsville, Florida, USA | FJ918508 | GQ267392 | FJ918553 |

| C. machaerinae | CBS 123183; CPC 15378 | Machaerina sinclairii | New Zealand | KX784636 | – | KX784706 |

| C. madagascariensis | CBS 114571; CPC 2253 | Soil | Madagascar | DQ190571 | GQ267395 | GQ267315 |

| CBS 114572; CPC 2252 | Soil | Madagascar | DQ190572 | GQ267394 | GQ267314 | |

| C. macroconidialis | CBS 114880; CPC 307 | E. grandis | South Africa | AF232855 | GQ267393 | GQ267313 |

| C. magnispora | CBS 136249; CMW 35184; CERC 1860 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | KJ462956 | KJ463071 | KJ462841 |

| C. malesiana | CBS 112710; CPC 3899 | Leaf litter | Thailand | AY725626 | AY725759 | AY725721 |

| CBS 112752; CPC 4223 | Soil | Sumatra, Indonesia | AY725627 | AY725760 | AY725722 | |

| C. maranhensis | CBS 134811 | Eucalyptus sp. | Açailândia, Maranhão, Brazil | KM395948 | KM396035 | KM395861 |

| CBS 134812 | Eucalyptus sp. | Açailândia, Maranhão, Brazil | KM395949 | KM396036 | KM395862 | |

| C. metrosideri | CBS 133603; LPF101 | Metrosideros polymorpha | Viçosa, Brazil | KC294313 | KC294304 | KC294310 |

| CBS 133604; LPF 103 | M. polymorpha | Viçosa, Brazil | KC294314 | KC294305 | KC294311 | |

| C. mexicana | CBS 110918; CPC 927 | Soil | Mexico | AF210863 | GQ267396 | FJ972526 |

| C. microconidialis | CBS 136636; CMW 31475; CERC 1810 | E. urophylla × E. grandis clone seedling leaf | CERC Nursery, Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China | KJ462959 | KJ463074 | KJ462844 |

| CBS 136638; CMW 31487; CERC 1822 | E. urophylla × E. grandis clone seedling leaf | CERC Nursery, Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China | KJ462960 | KJ463075 | KJ462845 | |

| C. monticola | CBS 140645; CPC 28835 | Soil | Thailand | KT964769 | KT964771 | KT964773 |

| CPC 28836 | Soil | Thailand | KT964770 | KT964772 | KT964774 | |

| C. mossambicensis | CBS 137243; CMW 36327 | E. grandis × E. camaldulensis cutting | Mozambique | – | JX570722 | JX570718 |

| C. multilateralis | CBS 110926: CPC 947 | Soil | Mexico | KX784639 | KX784578 | KX784709 |

| CBS 110927; CPC 948 | Soil | Mexico | KX784640 | KX784579 | KX784710 | |

| CBS 110931; CPC 956 | Soil | Mexico | KX784641 | – | KX784711 | |

| CBS 110932; CPC 957 | Soil | Mexico | KX784642 | KX784580 | KX784712 | |

| CBS 115606 | ||||||

| CBS 115615; CPC 915 | Soil | Mexico | KX784643 | KX784581 | KX784713 | |

| C. multinaviculata | CBS 134858; LPF233 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Mucuri, Bahia, Brazil | KM395985 | KM396072 | KM395898 |

| CBS 134859; LPF418 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Monte Dourado, Pará, Brazil | KM395986 | KM396073 | KM395899 | |

| C. multiphialidica | CBS 112678 | Soil | Cameroon | AY725628 | AY725761 | AY725723 |

| C. multiseptata | CBS 112682 | Eucalyptus sp. | Indonesia | DQ190573 | GQ267397 | FJ918535 |

| C. naviculata | CBS 101121 | Leaf litter | João Pessoa, Brazil | GQ267211 | GQ267399 | GQ267317 |

| CBS 116080 | Soil | Amazonas, Brazil | AF333409 | GQ267398 | GQ267316 | |

| C. nemicola | CBS 134837 | Soil | Araponga, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395979 | KM396066 | KM395892 |

| CBS 134838 | Soil | Araponga, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395980 | KM396067 | KM395893 | |

| C. orientalis | CBS 125259 | Soil | Teso East, Indonesia | GQ267237 | GQ267449 | GQ267357 |

| CBS 125260 | Soil | Lagan, Indonesia | GQ267236 | GQ267448 | GQ267356 | |

| C. ovata | CBS 111299 | E. tereticornis | Tucuruí, Pará, Brazil | GQ267212 | GQ267400 | GQ267318 |

| CBS 111307 | E. tereticornis | Tucuruí, Pará, Brazil | AF210868 | GQ267401 | GQ267319 | |

| C. pacifica | CBS 109063; CPC 2534; IMI 354528 | Araucaria heterophylla | Hawaii, USA | GQ267213 | AY725762 | AY725724 |

| CBS 114038; CPC 10717 | Ipomoea aquatica | Auckland, New Zealand | AY725630 | GQ267402 | GQ267320 | |

| C. papillata | CBS 136096; CMW 37972; CERC 1935 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangdong, China | KJ462963 | KJ463078 | KJ462848 |

| CBS 136097; CMW 37976; CERC 1939 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangdong, China | KJ462964 | KJ463079 | KJ462849 | |

| C. paracolhounii | CBS 114679; CPC 2445 | USA | KX784644 | KX784582 | KX784714 | |

| CBS 114705; CPC 2423 | USA | KX784645 | – | KX784715 | ||

| C. paraensis | CBS 134669; LPF430 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Monte Dourado, Pará, Brazil | KM395924 | KM396011 | KM395837 |

| LPF306 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Monte Dourado, Pará, Brazil | KM395925 | KM396012 | KM395838 | |

| C. parakyotensis | CBS 136085; CMW 35169; CERC 1845 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangdong, China | – | KJ463081 | KJ462851 |

| CBS 136095; CMW 35413; CERC 1904 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | – | KJ463082 | KJ462852 | |

| C. parva | CBS 110798; CPC 410 | Soil | South Africa | KX784646 | KX784583 | KX784716 |

| C. pauciramosa | CBS 138824; CMW 5683 | E. grandis | South Africa | FJ918514 | GQ267405 | FJ918565 |

| CMW 30823 | E. grandis | South Africa | FJ918515 | GQ280404 | FJ918566 | |

| C. penicilloides | CBS 174.55; IMI 299375 | Prunus sp. | Japan | AF333414 | GQ267406 | GQ267322 |

| C. pentaseptata | CBS 136087; CMW 35177; CERC 1853 | Eucalyptus leaf | Hainan, China | KJ462966 | KJ463083 | KJ462853 |

| CBS 136089; CMW 35377; CERC 1879 | Eucalyptus leaf | Hainan, China | KJ462967 | KJ463084 | KJ462854 | |

| C. piauiensis | CBS 134849 | Soil | Serra das Confusões, Piauí | KM395972 | KM396059 | KM395885 |

| CBS 134850 | Soil | Teresina, Piauí, Brazil | KM395973 | KM396060 | KM395886 | |

| C. pini | CBS 123698 | Pinus patula | Buga, Colombia | GQ267224 | GQ267436 | GQ267344 |

| CBS 125253 | P. patula | Buga, Colombia | GQ267225 | GQ267437 | GQ267345 | |

| C. polizzi | CBS 125270; CMW 7804 | Callistemon citrinus | Messina, Sicily, Italy | FJ972417 | GQ267461 | FJ972486 |

| CBS 125271; CMW 10151 | Arbustus unedo | Catania, Sicily, Italy | FJ972418 | GQ267462 | FJ972487 | |

| C. plurilateralis | CBS 111401; CPC 1637 | Ecuador | KX784648 | KX784586 | KX784719 | |

| C. pluriramosa | CBS 136976; CMW 31440; CERC 1774 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Fangchenggang, Guangxi, China | KJ462995 | KJ463112 | KJ462882 |

| C. propaginicola | CBS 134815; LPF220 | Eucalyptus sp. | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395953 | KM396040 | KM395866 |

| CBS 134816; LPF222 | Eucalyptus sp. | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395954 | KM396041 | KM395867 | |

| C. pseudobrassicae | CBS 134661; LPF260 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395935 | KM396022 | KM395848 |

| CBS 134662; LPF280 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395936 | KM396023 | KM395849 | |

| C. pseudocerciana | CBS 134823 | Eucalyptus sp. | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395961 | KM396048 | KM395874 |

| CBS 134824 | Eucalyptus seedling | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395962 | KM396049 | KM395875 | |

| C. pseudocolhounii | CBS 127195; CMW 27209 | E. dunnii | Fujian, China | HQ285788 | – | HQ285816 |

| CBS 127196; CMW 27213 | E. dunnii | Fujian, China | HQ285789 | – | HQ285817 | |

| C. pseudoecuadoriae | CBS 111402; CPC 1639 | Ecuador | KX784652 | KX784589 | KX784723 | |

| CBS 111412; CPC 1648 | Soil | Ecuador | DQ190601 | KX784590 | KX784724 | |

| C. pseudohodgesii | CBS 134818 | Azadirachta indica | Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395905 | KM395991 | KM395817 |

| CBS 134819 | A. indica | Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395906 | KM395992 | KM395818 | |

| C. pseudokyotensis | CBS 137332; CMW 31439; CERC 1774 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Fangchenggang, Guangxi, China | KJ462994 | KJ463111 | KJ462881 |

| C. pseudometrosideri | CBS 134844 | Eucalyptus sp. | Açailândia, Maranhão, Brazil | KM395908 | KM395994 | KM395820 |

| CBS 134845 | Soil | Maceió, Alagoas, Brazil | KM395909 | KM395995 | KM395821 | |

| C. pseudomexicana | CBS 130354 | Callistemon sp. | Tunisia | JN607281 | – | JN607496 |

| CBS 130355 | Callistemon sp. | Tunisia | JN607282 | – | JN607497 | |

| Ca. pseudonaviculata | CBS 114417; CPC 10926 | Buxus sempervirens | West Auckland, New Zealand | GQ267214 | GQ267409 | GQ267325 |

| CBS 116251; CPC 3399 | B. sempervirens | New Zealand | AF449455 | KM396000 | KM395826 | |

| C. pseudopteridis | CBS 163.28; IMI 299579 | Washingtonia robusta | USA | – | KM396076 | KM395902 |

| C. pseudoreteaudii | CBS 123694; CMW 25310 | Eucalyptus hybrid cutting | Guangdong, China | FJ918504 | GQ267411 | FJ918541 |

| CBS 123696; CMW 25292 | Eucalyptus hybrid cutting | Guangdong, China | FJ918505 | GQ267410 | FJ918542 | |

| C. pseudoscoparia | CBS 125255; CMW 15216 | E. grandis | Pichincha, Ecuador | GQ267227 | GQ267439 | GQ267347 |

| CBS 125256; CMW 15216 | E. grandis | Pichincha, Ecuador | GQ267228 | GQ267440 | GQ267348 | |

| C. pseudospathiphylli | CBS 109165; CPC 1623 | Soil | Ecuador | FJ918513 | GQ267412 | FJ918562 |

| C. pseudospathulata | CBS 134840 | Soil | Araponga, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395982 | KM396069 | KM395895 |

| CBS 134841 | Soil | Araponga, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395983 | KM396070 | KM395896 | |

| C. pseudouxmalensis | CBS 110923; CPC 941 | Soil | Mexico | KX784653 | – | KX784725 |

| CBS 110924; CPC 942 | Soil | Mexico | KX784654 | – | KX784726 | |

| CBS 115677; CPC 943 | Soil | Mexico | KX784655 | – | KX784727 | |

| C. pseudovata | CBS 134674; LPF267 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395945 | KM396032 | KM395858 |

| CBS 134675; LPF285 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395946 | KM396033 | KM395859 | |

| C. pteridis | CBS 111793; ATCC 34395; CPC 2372 | Arachnoides adiantiformis | USA | DQ190578 | GQ267413 | FJ918563 |

| CBS 111871; CPC 2443 | Pinus sp. | Spain | DQ190579 | GQ267414 | FJ918564 | |

| C. putriramosa | CBS 111449; CPC 1951 | Eucalyptus cutting | Brazil | KX784656 | KX784591 | KX784728 |

| CBS 111470; CPC 1940 | Soil | Brazil | KX784657 | KX784592 | KX784729 | |

| CBS 111477; CPC 1928 | Soil | Brazil | KX784658 | KX784593 | KX784730 | |

| CBS 116076; CPC 604 | Eucalyptus cutting | Brazil | GQ421776 | – | GQ421792 | |

| C. queenslandica | CBS 112146; CPC 3213 | E. urophylla | Australia | AF389835 | GQ267415 | FJ918543 |

| CBS 112155; CPC 3210 | E. pellita | Australia | AF389834 | GQ267416 | FJ918544 | |

| C. quinqueramosa | CBS 134654; LPF065 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Monte Dourado, Pará, Brazil | KM395942 | KM396029 | KM395855 |

| CBS 134655; LPF281 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Santana, Pará, Brazil | KM395943 | KM396030 | KM395856 | |

| C. reteaudii | CBS 112143; CPC 3200 | E. camaldulensis | Vietnam | GQ240642 | GQ267418 | FJ918536 |

| CBS 112144; CPC 3201 | E. camaldulensis | Vietnam | AF389833 | GQ267417 | FJ918537 | |

| C. robigophila | CBS 134652 | Eucalyptus sp. | Açailândia, Maranhão, Brazil | KM395937 | KM396024 | KM395850 |

| CBS 134653 | Eucalyptus sp. | Açailândia, Maranhão, Brazil | KM395938 | KM396025 | KM395851 | |

| C. rumohrae | CBS 109062; CPC 1603 | Adianthum sp. | Netherlands | AF232873 | GQ267420 | FJ918550 |

| CBS 111431; CPC 1716 | R. adiantiformis | Brazil | AF232871 | GQ267419 | FJ918549 | |

| C. seminaria | CBS 136631; CMW 31449; CERC 1784 | E. urophylla × E. grandis clone seedling leaf | CERC Nursery, Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China | KJ462997 | KJ463114 | KJ462884 |

| CBS 136632; CMW 31450; CERC 1785 | E. urophylla × E. grandis clone seedling leaf | CERC Nursery, Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China | KJ462998 | KJ463115 | KJ462885 | |

| C. silvicola | CBS 134836 | Soil | Araponga, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395975 | KM396062 | KM395888 |

| CBS 135237 | Soil | Araponga, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395978 | KM396065 | KM395891 | |

| C. spathulata | CBS 555.92 | E. viminalis | Brazil | AF308463 | GQ267426 | FJ918554 |

| CBS 115639; CPC 1148 | Colombia | KX784659 | KX784594 | KX784732 | ||

| CBS 115644; CPC 1071 | E. grandis | Colombia | KX784660 | KX784595 | KX784733 | |

| C. spathiphylli | CBS 114540; ATCC 44730; CPC 2378 | Spathiphyllum sp. | USA | AF348214 | GQ267424 | GQ267330 |

| CBS 116168; CPC 789 | Spathiphyllum sp. | Switzerland | FJ918512 | GQ267425 | FJ918561 | |

| C. sphaeropendunculata | CBS 136081; CMW 31390; CERC 1725 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | KJ463003 | KJ463120 | KJ462890 |

| C. stipitata | CBS 112513; CPC 3851 | Eucalyptus sp. | Colombia | KX784661 | KX784596 | KX784734 |

| C. sulawesiensis | CBS 125253; CMW 14879 | Eucalyptus sp. | Sulawesi, Indonesia | GQ267220 | GQ267432 | GQ267340 |

| CBS 125277 | Eucalyptus sp. | Sulawesi, Indonesia | GQ267222 | GQ267434 | GQ267342 | |

| C. sumatrensis | CBS 112829; CPC 4518 | Soil | Sumatra, Indonesia | AY725649 | AY725771 | AY725733 |

| CBS 112934; CPC 4516 | Soil | Indonesia | AY725651 | AY725773 | AY725735 | |

| C. syzygiicola | CBS 112827; CPC 4512 | S. aromaticum | Indonesia | KX784662 | KX784597 | KX784735 |

| CBS 112831; CPC 4511 | S. aromaticum | Indonesia | KX784663 | – | KX784736 | |

| C. telluricola | CBS 134663; LPF214 | Soil | Salinas, Minas Gerais, Brazil | KM395929 | KM396016 | KM395842 |

| CBS 134664; LPF217 | Soil | Mucuri, Bahia, Brazil | KM395930 | KM396017 | KM395843 | |

| C. tereticornis | CBS 111301; CPC 1429 | E. tereticornis | Brazil | KX784664 | – | KX784737 |

| C. terrae-reginae | CBS 112151; CPC 3202 | E. urophylla | Queensland, Australia | FJ918506 | GQ267451 | FJ918545 |

| CBS 112634; CPC 4233 | Xanthorrhoea australis | Victoria, Australia | FJ918507 | GQ267452 | FJ918546 | |

| C. terrestris | CBS 136642; CMW 35180; CERC 1856 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangdong, China | KJ463004 | KJ463121 | KJ462891 |

| CBS 136643; CMW 35364; CERC 1868 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangdong, China | KJ463005 | KJ463122 | KJ462892 | |

| C. terricola | CBS 116247; CPC 3583 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Brazil | KX784665 | – | KX784738 |

| CBS 116248; CPC 3536 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Brazil | KX784666 | – | KX784739 | |

| C. tetraramosa | CBS 136635; CMW 31474; CERC 1809 | E. urophylla × E. grandis clone seedling leaf | CERC Nursery, Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China | KJ463011 | KJ463128 | KJ462898 |

| CBS 136637; CMW 31476; CERC 1811 | E. urophylla × E. grandis clone seedling leaf | CERC Nursery, Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China | KJ463012 | KJ463129 | KJ462899 | |

| C. tropicalis | CBS 116242; CPC 3543 | Eucalyptus sp. | Brazil | KX784668 | – | KX784741 |

| CBS 116271; CPC 3559 | Eucalyptus sp. | Brazil | KX784669 | KX784599 | KX784742 | |

| C. turangicola | CBS 136077; CMW 31411; CERC 1746 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Fangchenggang, Guangxi, China | KJ463013 | – | KJ462900 |

| CBS 136093; CMW 35410; CERC 1901 | Soil in Eucalyptus plantation | Guangxi, China | KJ463014 | KJ463130 | KJ462901 | |

| C. tunisiana | CBS 130356 | Callistemon sp. | Tunisia | JN607277 | – | JN607292 |

| CBS 130357 | C. laevis | Tunisia | JN607276 | – | JN607291 | |

| C. uniseptata | CBS 413.67; CPC 2391; IMI 299577 | Paphiopedilum callosum | Celle, Germany | GQ267208 | GQ267379 | GQ267307 |

| CBS 170.77; IMI 299388 | Idesia polycarpa | Auckland, New Zealand | GQ267209 | GQ267380 | GQ267308 | |

| C. uxmalensis | CBS 110919; CPC 928 | Soil | Mexico | KX784637 | – | KX784707 |

| CBS 110925; CPC 945 | Soil | Mexico | KX784638 | – | KX784708 | |

| C. variabilis | CBS 112691; CPC 2506 | Theobroma grandiflorum | Brazil | GQ267240 | GQ267458 | GQ267335 |

| CBS 114677; CPC 2436 | Schefflera morotoni | Brazil | AF333424 | GQ267457 | GQ267334 | |

| C. venezuelana | CBS 111052; CPC 1183 | Venezuela | KX784671 | KX784601 | KX784744 | |

| Ca. zuluensis | CBS 125268 | E. grandis | South Africa | FJ972414 | GQ267459 | FJ972483 |

| CBS 125272 | E. grandis | South Africa | FJ972415 | GQ267460 | FJ972484 | |

| Calonectria sp. | CBS 111423; CPC 1650 | Ecuador | KX784673 | KX784603 | KX784746 | |

| CBS 111465; CPC 1902 | Soil | Brazil | DQ190607 | KX784584 | KX784717 | |

| CBS 111706; CPC 1636 | Ecuador | KX784674 | KX784604 | KX784747 | ||

| CBS 112152; CPC 3203 | E. camaldulensis | Vietnam | KX784672 | KX784602 | KX784745 | |

| CBS 112753; CPC 4225 | Indonesia | KX784667 | KX784598 | KX784740 | ||

| CBS 113496; CPC 3155 | KX784675 | KX784605 | KX784748 | |||

| CBS 113627; CPC 3232 | KX784676 | KX784606 | KX784749 | |||

| CBS 114164; CPC 1634 | Ecuador | KX784677 | KX784607 | KX784750 | ||

| CBS 114691; CPC 2472; AR 2574 | Canada | KX784678 | KX784608 | KX784751 | ||

| CBS 114755; CPC 1403 | E. tereticornis | Brazil | KX784670 | KX784600 | KX784743 | |

| CBS 116108; CPC 726 | Soil | Colombia | KX784647 | KX784585 | KX784718 | |

| CBS 116249; CPC 3533 | Eucalyptus sp. | Brazil | KX784679 | KX784609 | KX784752 | |

| CBS 116265; CPC 3552 | Eucalyptus sp. | Brazil | KX784680 | KX784610 | KX784753 | |

| CBS 116305; CPC 3890 | Eucalytus sp. | Brazil | KX784634 | KX784576 | KX784704 | |

| CBS 116319; CPC 3761 | Eucalytus sp. | Brazil | KX784635 | KX784577 | KX784705 | |

| Curvicladiella cignea | CBS 109167; CPC 1595; MUCL 40269 | Leaf litter | French Guiana | KM232002 | KM231287 | KM231867 |

AR: Amy Y. Rossman working collection; ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA; CBS: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CERC: China Eucalypt Research Centre, Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China; CMW: culture collection of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa; CPC: Pedro Crous working collection housed at CBS; IMI: International Mycological Institute, CABI-Bioscience, Egham, Bakeham Lane, UK; LPF: Laboratório de Patologia Florestal, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil; MUCL: Mycothèque, Laboratoire de Mycologie Systématique st Appliqée, l’Université, Louvian-la-Neuve, Belgium; UFV: Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil. Isolates obtained during the survey indicated in grey blocks.

tub2 = β-tubulin, cmdA = calmodulin, tef1 = translation elongation factor 1-alpha. Ex-type isolates indicated in bold. Sequences generated in this study indicated in italics.

Phylogeny

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 7-d-old axenic cultures, grown on MEA at room temperature, using the UltraClean™ Microbial DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., California, USA) following the protocols provided by the manufacturer. Based on previous studies (Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2015b, Alfenas et al., 2015), partial gene sequences were determined for β-tubulin (tub2), calmodulin (cmdA), and the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1) regions as these regions provided the best phylogenetic signal at species level for the genus Calonectria. Therefore, the primers and protocols described by Lombard et al. (2015b) were used to determine these regions.

To ensure the integrity of the sequences, the amplicons were sequenced in both directions using the same primers used for amplification. Consensus sequences for each locus were assembled in MEGA v. 7 (Kumar et al. 2016) and compared with representative sequences from Alfenas et al., 2013a, Alfenas et al., 2013b, Alfenas et al., 2015, Chen et al., 2011 and Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2011, Lombard et al., 2015a. Subsequent alignments for each locus were generated in MAFFT v. 7.110 (Katoh & Standley 2013) and the ambiguously aligned regions of both ends were truncated. Congruency of the three loci was tested using the 70 % reciprocal bootstrap criterion (Mason-Gamer & Kellogg 1996) following the protocols of Lombard et al. (2015b).

Phylogenetic analyses of the individual gene regions and the combined dataset were based on Bayesian inference (BI), Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Maximum Parsimony (MP). For BI and ML, the best evolutionary models for each locus were determined using MrModeltest (Nylander 2004) and incorporated into the analyses. MrBayes v. 3.2.1 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) was used for BI to generate phylogenetic trees under optimal criteria for each locus. A Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm of four chains was initiated in parallel from a random tree topology with the heating parameter set at 0.3. The MCMC analysis lasted until the average standard deviation of split frequencies was below 0.01 with trees saved every 1 000 generations. The first 25 % of saved trees were discarded as the “burn-in” phase and posterior probabilities (PP) were determined from the remaining trees.

The ML analyses were preformed using RAxML v. 8.0.9 (randomised accelerated (sic) maximum likelihood for high performance computing; Stamatakis 2014) through the CIPRES website (http://www.phylo.org) to obtain another measure of branch support. The robustness of the analysis was evaluated by bootstrap support (BS) with the number of bootstrap replicates automatically determined by the software.

For MP, analyses were done using PAUP (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony, v. 4.0b10; Swofford 2003) with phylogenetic relationships estimated by heuristic searches with 1 000 random addition sequences. Tree-bisection-reconnection was used, with branch swapping option set on “best trees” only. All characters were weighted equally and alignment gaps treated as fifth state. Measures calculated for parsimony included tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI) and rescaled consistence index (RC). Bootstrap analyses (Hillis & Bull 1993) were based on 1 000 replications. All new sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 1) and alignments and trees in TreeBASE.

Taxonomy

Axenic cultures were transferred to synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA; Nirenburg 1981) and incubated at room temperature for 7 d. Gross morphological characteristics were studied by mounting the fungal structures in 85 % lactic acid and 30 measurements were made at ×1 000 magnification for all taxonomically informative characters using a Zeiss Axioscope 2 microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) illumination. The 95 % confidence levels were determined for the conidial measurements with extremes given in parentheses. For all other fungal structures measured, only the extremes are provided. Colony colour was assessed using 7-d-old cultures on MEA incubated at room temperature and the colour charts of Rayner (1970). All descriptions, illustrations and nomenclatural data were deposited in MycoBank (Crous et al. 2004a).

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

Approximately 500−550 bases were determined for the three gene regions included in this study. The congruency analyses revealed no conflicts in tree topologies, with only minor differences in branch support. Therefore, the sequences of the three loci determined here were combined in a single dataset for analyses. For the BI and ML analyses, a HKY+I+G model was selected for all three gene regions and incorporated into the analyses. The ML tree topology confirmed the tree topologies obtained from the BI and MP analyses, and therefore, only the ML tree is presented.

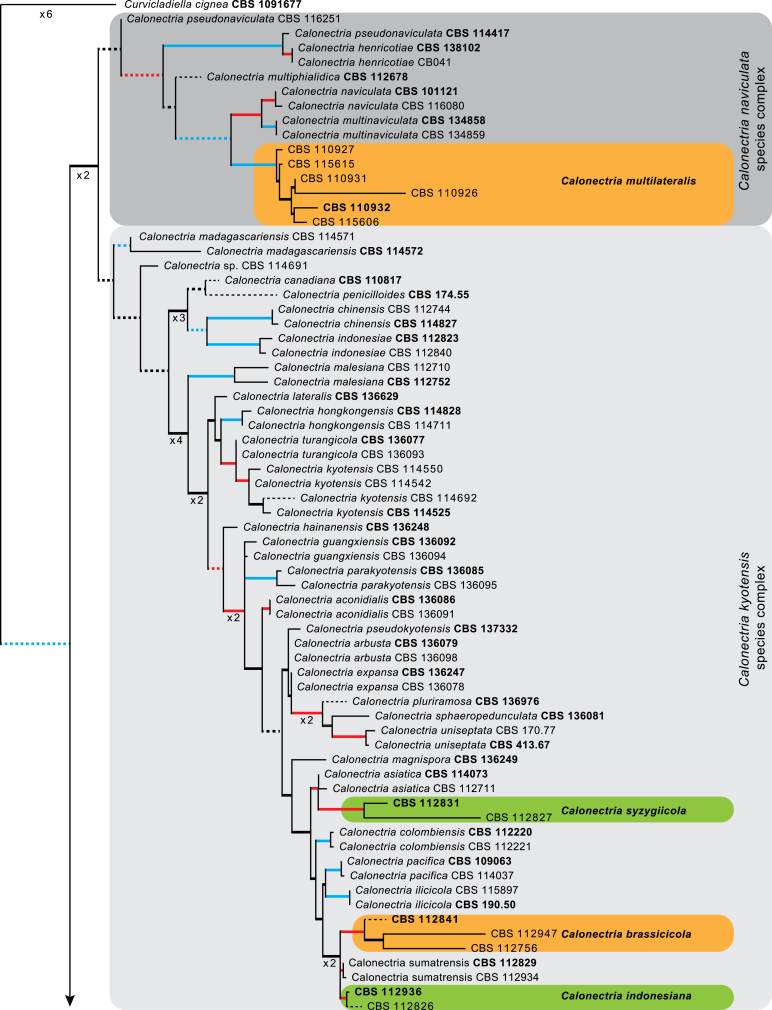

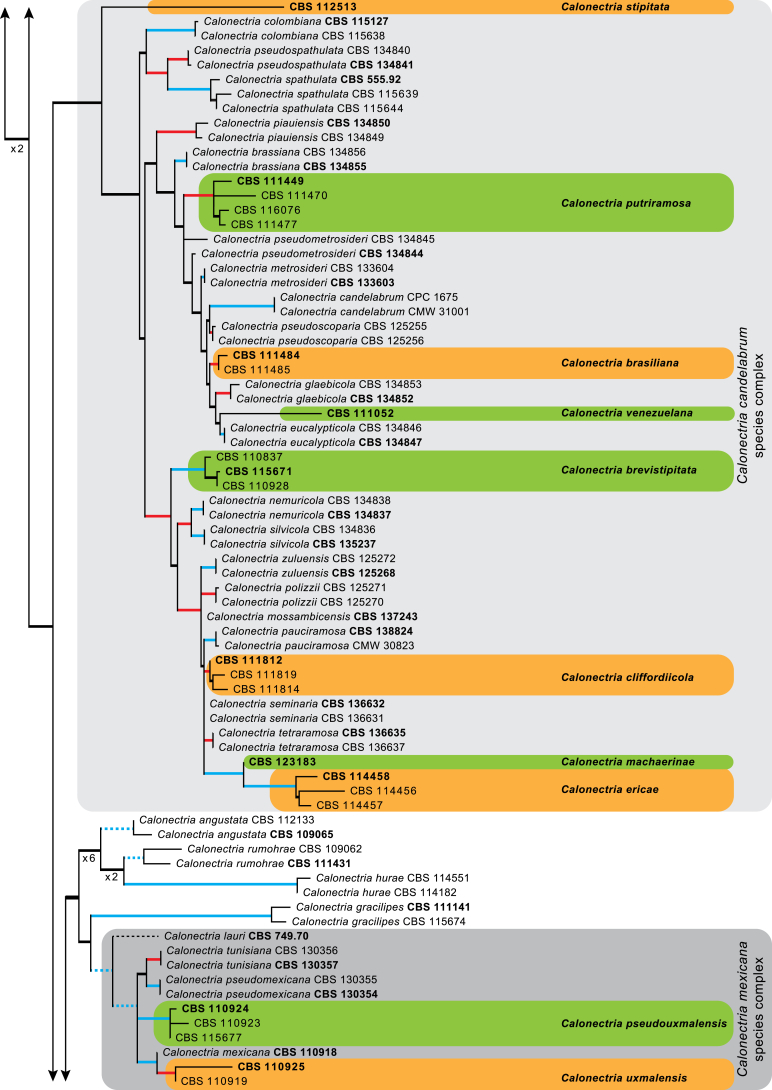

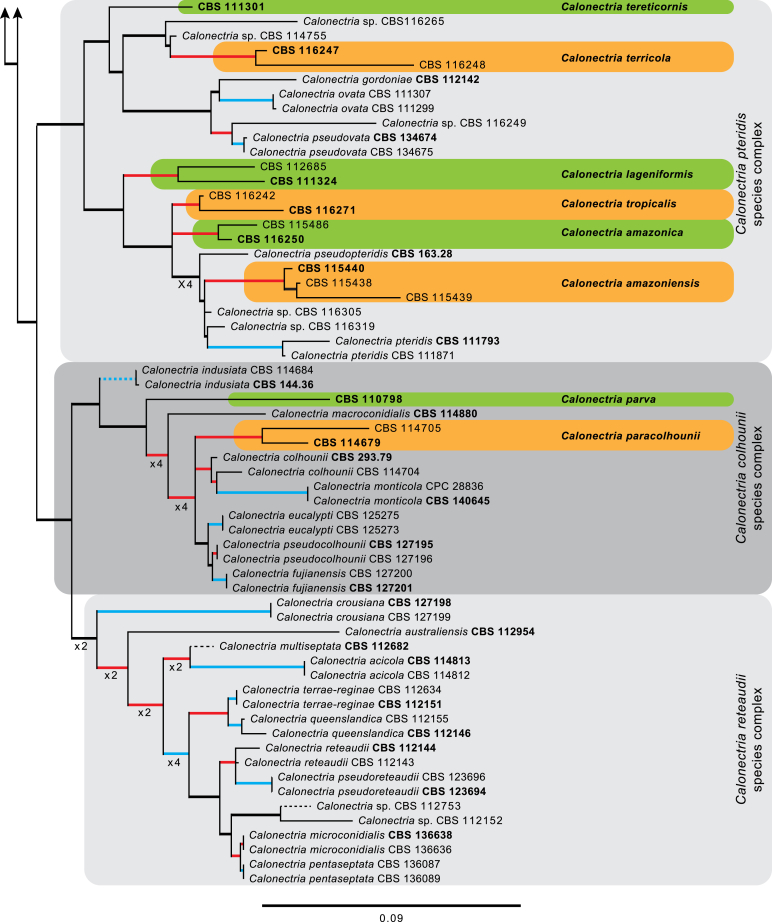

The combined cmdA, tef1 and tub2 sequences dataset included 278 ingroup taxa and Curvicladiella cignea (CBS 109167) as outgroup taxon. This dataset consisted of 1 680 characters, of which 507 were constant, 198 parsimony-uninformative and 975 parsimony-informative. The MP analysis yielded 1 000 trees (TL = 6 998; CI = 0.344; RI = 0.867; RC = 0.298) and a single best ML tree with −InL = −32198.651254 which is presented in Fig. 1. The BI lasted for 10 M generations, and the consensus tree, with posterior probabilities, was calculated from 15 002 trees left after 5 000 trees were discarded as the ‘burn-in’ phase. In the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1) the previously unnamed Calonectria species resolved in 21 distinct clades that were either well or strongly supported and 17 single lineages, each representing probable novel phylogenetic taxa.

Fig. 1.

The ML consensus tree inferred from the combined cmdA, tef1 and tub2 sequence alignments. Thickened lines indicate branches present in the ML, MP and Bayesian consensus trees. Branches with ML-BS & MP-BS = 100 % and PP = 1.00 are in blue. Branches with ML-BS & MP-BS ≥ 75 % and PP ≥ 0.95 are in red. Dashed lines indicate branches shortened ×10. The scale bar indicates 0.09 expected changes per site. The tree is rooted to Curvicladiella cignea (CBS 109167). Epi- and ex-type strains are indicated in bold.

Taxonomy

Based on phylogenetic inference supported by morphological observations, numerous Calonectria isolates included in this study represent novel species. No sexual morphs were observed for any of the novel taxa described below, even after 6 wk of incubation at room temperature. Fifteen of the lineages (CBS 111423, CBS 111468, CBS 111706, CBS 112152, CBS 112753, CBS 113496, CBS 113627, CBS 114164, CBS 114691, CBS 114755, CBS 116108, CBS 116249, CBS 116265, CBS 116305, CBS 116319) identified based on phylogenetic inference are not provided with names because they form part of a separate study (Crous et al. in prep.) or more taxa are required to resolve their phylogenetic position.

Calonectria amazonica L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818698. Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Calonectria amazonica (ex-type CBS 116250). A. Macroconidiophore. B–C. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and allantoid to elongate doliiform to reniform phialides. D–E. Clavate vesicles. F–G. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A = 50 μm; B−G = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the Amazonian region of Brazil where this fungus was collected.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 75–190 × 6–8 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 180–270 μm long, 4–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a clavate vesicle, 5–6 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 45–55 μm wide, and 60–80 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 22–32 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 14–24 × 3–5 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 10–18 × 2–4 μm; quaternary branches aseptate, 10−15 × 3 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–4 phialides; phialides allantoid to elongate doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 9–20 × 3–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight to slightly curved, (68–)74–84(–88) × (4−)4.5−5.5(−6) μm (av. 79 × 5 μm), 1(−3)-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (40−65 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface sienna to sepia with moderate white, wooly aerial mycelium and moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse sienna to sepia with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimens examined: Brazil, Amazon, from foliar lesion of Eucalyptus tereticornis, 1993, P.W. Crous & A.C. Alfenas (holotype CBS-H22750, culture ex-type CBS 116250 = CPC 3534); ibid., cultures CBS 115486 = CPC 3894.

Notes: Calonectria amazonica resides in the C. pteridis complex. The macroconidia of C. amazonica [(68–)74–84(–88) × (4−)4.5−5.5(−6) μm (av. 79 × 5 μm)] are slightly smaller than those of C. pteridis and C. pseudopteridis [(50–)70–100(–130) × (4−)5−6 μm (av. 82 × 5.5 μm); Crous, 2002, Alfenas et al., 2015], but larger than those of C. amazoniensis, C. lageniformis and C. tropicalis (see below).

Calonectria amazoniensis L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818699. Fig. 3.

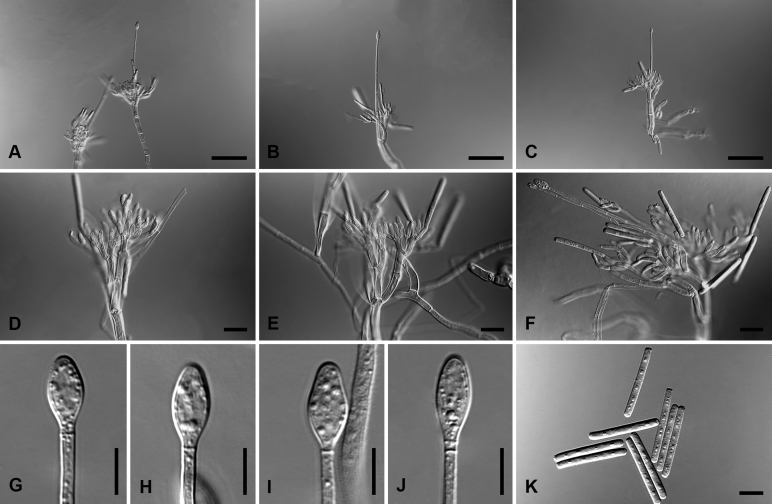

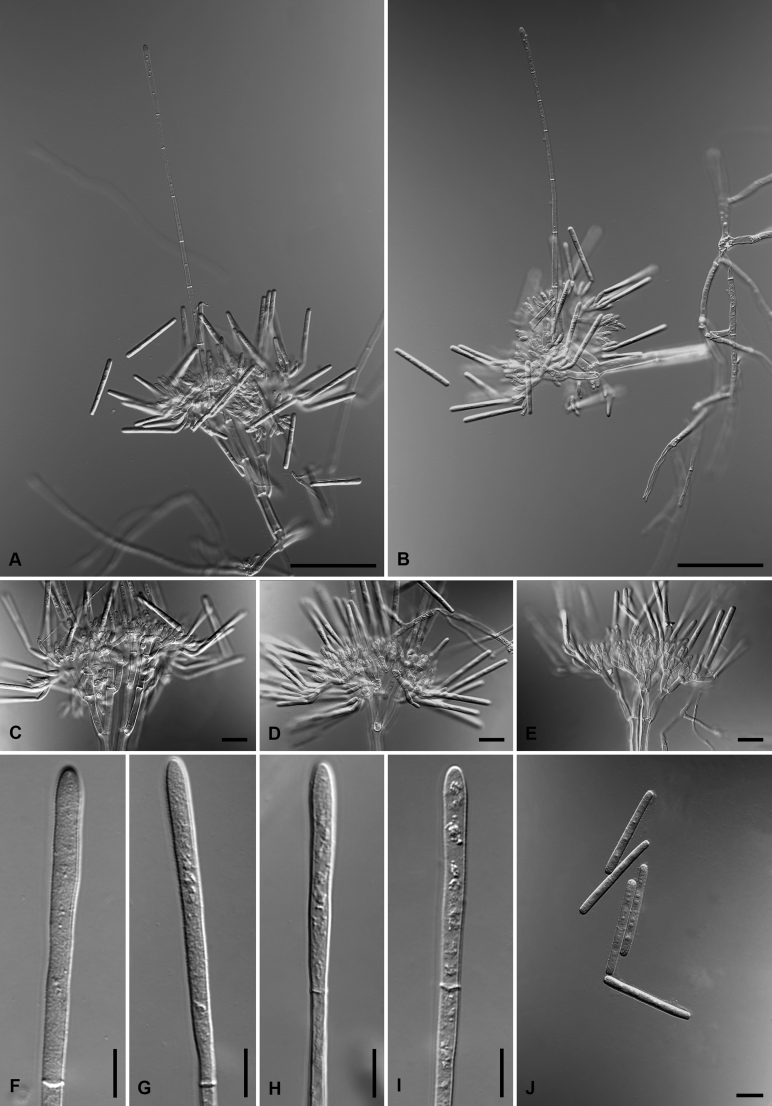

Fig. 3.

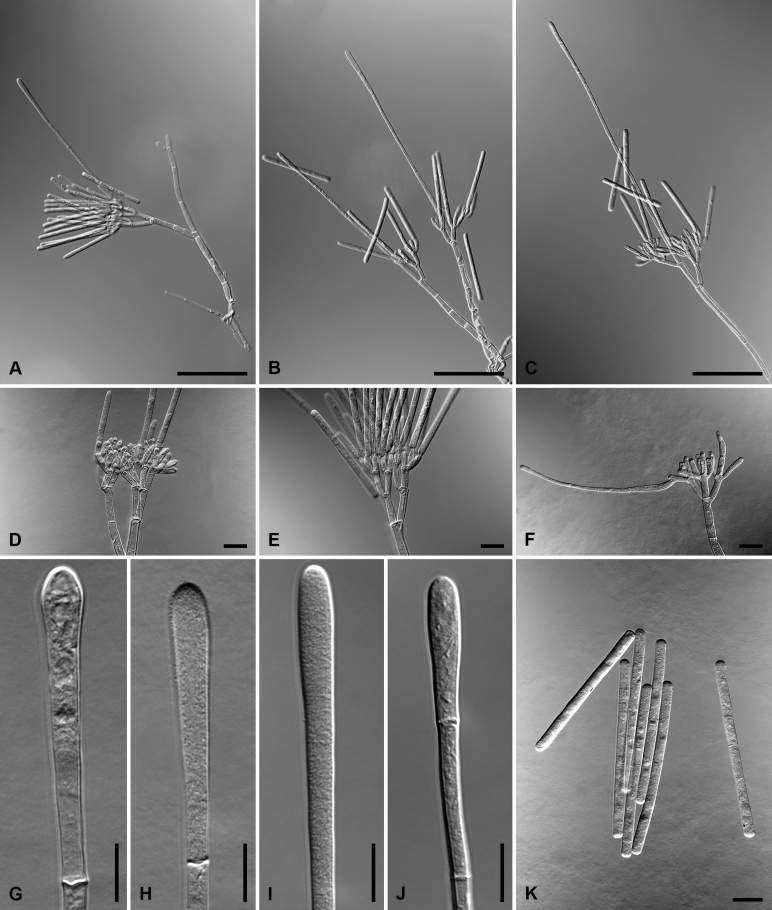

Calonectria amazoniensis (ex-type CBS 115440). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–E. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and elongate doliiform to reniform phialides. F. Conidiogenous apparatus with lateral stipe extension. G–J. Clavate vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the Amazonian region of Brazil where this fungus was collected.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 45–240 × 6–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 140–280 μm long, 4–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a clavate vesicle, 5–7 μm diam; lateral stipe extensions (90° to main axis) few, 80–95 μm long, 2–4 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in clavate vesicles, 2–3 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 30–110 μm wide, and 30–100 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 15–31 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–26 × 3–5 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 9–31 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches and additional branches (−5) aseptate, 9−18 × 3–5 μm each terminal branch producing 2–4 phialides; phialides elongate doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 7–17 × 3–5 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight to slightly curved, (56–)64–74(–75) × (4−)4.5−5.5(−6) μm (av. 69 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (40−65 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface sienna to amber with moderate white, wooly aerial mycelium and moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse sienna with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimens examined: Brazil, Amazon, from foliar lesion of Eucalyptus tereticornis, 1993, P.W. Crous & A.C. Alfenas (holotype CBS-H22751 culture ex-type CBS 115440 = CPC 3885); ibid., cultures CBS 115438 = CPC 3890, CBS 115439 = CPC 3889.

Notes: Calonectria amazoniensis resides in the C. pteridis complex. This species can be distinguished from other species in the C. pteridis complex by its greater number (−5) of branches in the conidiogenous apparatus and the presence of lateral stipe extensions (Crous, 2002, Alfenas et al., 2015).

Calonectria brasiliana L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818700. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Calonectria brasiliana (ex-type CBS 111484). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. G–J. Ellipsoid to obpyrifom vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to Brazil, the country where this fungus was collected.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 40–240 × 5–10 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 117–172 μm long, 4–6 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in an ellipsoid to obpyriform vesicle, 6–9 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 45–100 μm wide, and 40–70 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 16–23 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–17 × 3–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 7–13 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches and additional branches (–5) aseptate, 7–14 × 3–4 μm each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 7–12 × 3–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (36–)38–42(–46) × (3−)3.5−4.5(−5) μm (av. 40 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (30−60 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface cinnamon to brick with sparse, felty, white aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse cinnamon to sepia with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimens examined: Brazil, from soil, Jun. 1998, A.C. Alfenas (holotype CBS-H22752, culture ex-type CBS 111484 = CPC 1924); ibid., culture CBS 111485 = CPC 1929.

Notes: Calonectria brasiliana is a new species in the C. candelabrum complex (Schoch et al., 1999, Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2015a). The macroconidia of C. brasiliana [(36–)38–42(–46) × (3−)3.5−4.5(−5) μm (av. 40 × 4 μm)] are smaller than those of its closest phylogenetic neighbours (Fig. 1): C. candelabrum [(45–)58–68(–80) × 4−5(−6) μm (av. 60 × 4.5 μm); Crous 2002], C. eucalypticola [(43–)49–52(–55) × 3−5 μm (av. 50 × 4 μm); Alfenas et al. 2015], C. glaebicola [(45–)50–52(–55) × 3−5 μm (av. 50 × 4 μm); Alfenas et al. 2015], C. metrosideri [(40–)44–46(–51) × 3−5 μm (av. 45 × 4 μm); Alfenas et al., 2013a, Alfenas et al., 2015], C. pseudometrosideri [(40–)49–52(–60) × (3−)4.5(−5) μm (av. 51 × 4.5 μm); Alfenas et al. 2015] and C. pseudoscoparia [(41–)45–51(–52) × 3−5 μm (av. 48 × 4 μm); Lombard et al. 2010b].

Calonectria brassicicola L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818701. Fig. 5.

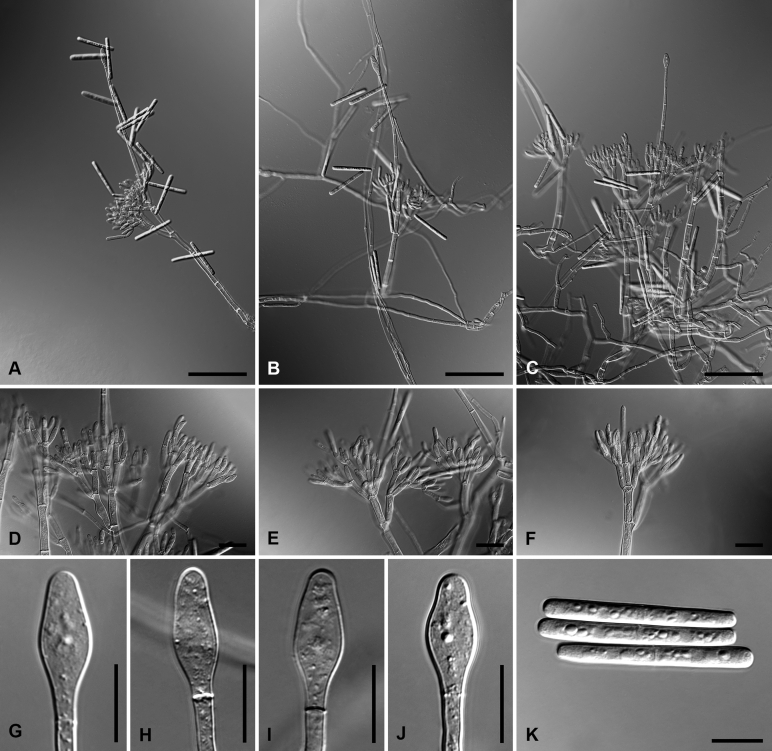

Fig. 5.

Calonectria brassicicola (ex-type CBS 112841). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–F. Conidiogenous apparatus with lateral stipe extensions and doliiform to reniform phialides. G–J. Sphaeropedunculate vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the host plant, Brassica, from which this fungus was isolated.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicles; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 30–90 × 6–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 90–140 μm long, 4–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a sphaeropedunculate vesicle, 6–10 μm diam; lateral stipe extensions (90° to main axis) sparse, 30–50 μm long, 2–4 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in sphaeropedunculate vesicles, 3−5 μm. Conidiogenous apparatus 45–80 μm wide, and 35–50 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 12–20 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 8–13 × 3–5 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 8–12 × 3–6 μm; quaternary branches aseptate, 8–11 × 2–5 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 7–15 × 3–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (36−)39–45(–48) × (4−)4.5–5.5(−6) μm (av. 42 × 5 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (50−65 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface buff with abundant white to buff, wooly aerial mycelium, and moderate sporulation on the colony surface; reverse sienna, chlamydospores not observed.

Specimens examined: Indonesia, from soil at Brassica sp., 1990s, M.J. Wingfield (holotype CBS-H22753, culture ex-type CBS 112841 = CPC 4552); ibid., culture CBS 112756 = CPC 4502. New Zealand, substrate unknown, 2001, C.F. Hill, Lynfield 484, culture CBS 112947 = CPC 4668.

Notes: Calonectria brassicicola is similar to C. sumatrensis in having few lateral stipe extensions (Crous et al. 2004b). The macroconidia of C. brassicicola [(36−)39–45(–48) × (4−)4.5–5.5(−6) μm (av. 42 × 5 μm)] are smaller than those of C. sumatrensis [(45−)55–65(–70) × (4.5–)5(−6) μm (av. 58 × 5 μm); Crous et al. 2004b].

Calonectria brevistipitata L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818702. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Calonectria brevistipitata (ex-type CBS 115671). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–E. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and elongate doliiform to reniform phialides. F. Conidiogenous apparatus with lateral stipe extension. G–J. Fusiform to ellipsoid vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the short stipe extensions of the macroconidiophores in this fungus.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 50–210 × 5–12 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 90–135 μm long, 2–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in an fusiform to obpyriform vesicle, 5–8 μm diam; lateral stipe extensions (90° to main axis) abundant, 60–80 μm long, 2–3 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in broadly clavate vesicles, 2–3 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 45–75 μm wide, and 45–70 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 13–25 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–19 × 3–5 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 8–16 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches aseptate, 7–11 × 3–4 μm each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides elongate doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 6–11 × 2–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, 29–33(–35) × 3−4 μm (av. 31 × 3.5 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (40−70 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface cinnamon to brick to sienna with abundant, wooly, white to buff aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse cinnamon to sepia with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimens examined: Mexico, from soil, Apr. 1994, P.W. Crous (holotype CBS-H22754, culture ex-type CBS 115671 = CPC 949); ibid., cultures CBS 110837 = CPC 913, CBS 110928 = CPC 951.

Notes: Calonectria brevistipitata is a new species in the C. candelabrum complex. The lateral stipe extensions (up to 80 μm long) and macroconidia [29–33(–35) × 3−4 μm (av. 31 × 3.5 μm) of C. brevistipitata are shorter than the lateral stipe extensions (up to 125 μm long) and macroconidia [(35–)36–40(–43) × (3−)3.5−4.5(−5) μm (av. 38 × 4 μm)] of C. machaerinae, the only other species in the C. candelabrum complex to produce lateral stipe extensions.

Calonectria cliffordiicola L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818703. Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Calonectria cliffordiicola (ex-type CBS 111812). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. G–J. Ellipsoid to obpyrifom vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to plant host plant genus, Cliffordia, from which this fungus was isolated.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 65–130 × 7–10 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 127–180 μm long, 4–6 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in an ellipsoid to obpyriform vesicle, 7–9 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 57–100 μm wide, and 40–85 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 15–32 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 11–23 × 3–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 7–13 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches aseptate, 8–13 × 3–4 μm each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 7–11 × 3–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (35–)38–42(–44) × (3−)3.5−4.5(−6) μm (av. 40 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (35−65 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface cinnamon to brick with sparse, felty, white to buff aerial mycelium and moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse cinnamon to sepia with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimens examined: South Africa, Western Cape Province, George, from Cliffordia feruginea, 14 Apr. 1998, P.W. Crous (holotype CBS-H22755, culture ex-type CBS 111812 = CPC 2631); Stellenbosch, from Prunus avium saplings, 1 May 1999, C. Linde, cultures CBS 111814 = CPC 2617, CBS 111819 = CPC 2604.

Notes: Calonectria cliffordiicola is a new species in the C. candelabrum complex (Schoch et al., 1999, Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2015a). Morphologically, this species shows some overlap with C. brasiliana, but can be distinguished by its shorter stipe extensions (up to 180 μm) compared to C. brasiliana (up to 240 μm).

Calonectria ericae L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818704. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Calonectria ericae (ex-type CBS 114458). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. G–J. Ellipsoid to obpyriform vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to host plant genus, Erica, from which this species was isolated.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 40–100 × 6–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 105–160 μm long, 3–7 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in an ellipsoid to obpyriform vesicle, 6–10 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 40–75 μm wide, and 35–70 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 15–23 × 3–5 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–19 × 2–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 6–16 × 2–5 μm; quaternary branches aseptate, 6–13 × 2–5 μm each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides elongate doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 6–11 × 2–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (29–)34–40(–42) × (3−)3.5−4.5(−5) μm (av. 37 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (40−65 mm diam) on MEA after 7 days at room temperature; surface cinnamon to brick with sparse, felty, white aerial mycelium and moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse cinnamon to umber with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimens examined: USA, California, from Erica capensis, Sep. 1998, S.T. Koike (holotype CBS-H22756, culture ex-type CBS 114458 = CPC 2019); ibid., cultures CBS 114456 = CPC 1984, CBS 114457 = CPC 1985.

Notes: Calonectria ericae is a new species in the C. candelabrum complex. This species produces the smallest macroconidia in the C. candelabrum complex. Kioke et al. (1999) initially identified these isolates as C. pauciramosa based on morphology and mating studies using the C. pauciramosa mating tester strains (Schoch et al., 1999, Lombard et al., 2010a).

Calonectria indonesiana L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818705. Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Calonectria indonesiana (ex-type CBS 112936). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–E. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. F. Conidiogenous apparatus with lateral stipe extension. G–J. Sphaeropedunculate vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to Indonesia, the country where this fungus was collected.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicles; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 35–115 × 6–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 110–130 μm long, 3–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a sphaeropedunculate vesicle, 8–10 μm diam; lateral stipe extensions (90° to main axis) sparse, 30–50 μm long, 3–4 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in sphaeropedunculate vesicles, 4−5 μm. Conidiogenous apparatus 40–100 μm wide, and 40–70 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 11–20 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 8–17 × 4–7 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 9–14 × 3–6 μm; quaternary branches and additional branches (−6) aseptate, 7–12 × 3–5 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 7–14 × 3–5 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (38−)40–46(–48) × (3−)4.5–5.5(−6) μm (av. 43 × 5 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (50−65 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface buff with abundant white to buff, wooly aerial mycelium, and moderate sporulation on the colony surface; reverse sienna, chlamydospores not observed.

Specimens examined: Indonesia, north Sumatera, from soil, 1998, M.J. Wingfield (holotype CBS-H22757, culture ex-type CBS 112936 = CPC 4504); ibid., culture CBS 112826 = CPC 4519.

Notes: Calonectria indonesiana is similar to C. brassicicola and C. sumatrensis in having few lateral stipe extensions (Crous et al. 2004b). Calonectria indonesiana (−6) can be distinguished from C. brassicicola (−4) and C. sumatrensis (−3) by the number of branches of the conidiogenous apparatus (Crous et al. 2004b).

Calonectria lageniformis L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818706. Fig. 10.

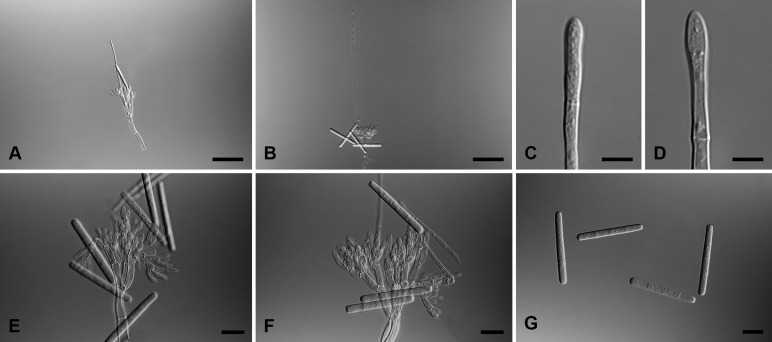

Fig. 10.

Calonectria lageniformis (ex-type CBS 111324). A–B. Macroconidiophores. C–E. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. F–I. Lageniformis to ellipsoid vesicles. J. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–B = 50 μm; C–J = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the characteristic lageniform vesicles in this fungus.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 65–220 × 4–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 135–185 μm long, 4–6 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a lageniform to ellipsoid vesicle, 6–10 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 20–80 μm wide, and 35–60 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 16–28 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–18 × 3–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 8–13 × 3–6 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–4 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 7–11 × 3–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (35–)37–43(–45) × (3−)4.5−5.5(−6) μm (av. 40 × 5 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies fast growing (60−90 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface sepia with sparse buff, felty aerial mycelium and moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse sepia with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimens examined: Brazil, from leaf lesion on Eucalyptus sp., 1993, P.W. Crous & A.C. Alfenas, culture CBS 112685 = CPC 3418. Mauritius, Rivière Noire, from foliar lesion on Eucalyptus sp., 10 Apr. 1996, H. Smith (holotype CBS-H22758 culture ex-type CBS 111324 = CPC 1473).

Note: Calonectria lageniformis is the only species that has lageniform vesicles (Crous, 2002, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2015a, Alfenas et al., 2015).

Calonectria machaerinae L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818707. Fig. 11.

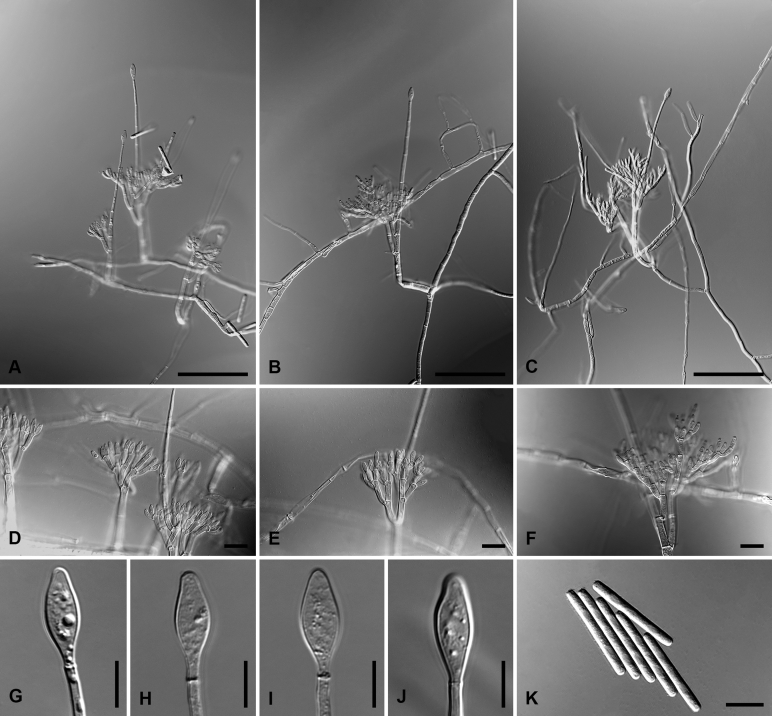

Fig. 11.

Calonectria machaerinae (ex-type CBS 123183). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–E. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. F. Conidiogenous apparatus with lateral stipe extension. G–J. Ellipsoid to obpyriform vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to plant host genus, Machaerina, from which this species was isolated.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 40–115 × 5–10 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 105–170 μm long, 3–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in an ellipsoid to obpyriform vesicle, 6–9 μm diam; lateral stipe extensions (90° to main axis) few, 80–125 μm long, 3–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in broadly clavate vesicles, 5–6 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 40–80 μm wide, and 55–90 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 18–28 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 13–23 × 3–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 8–19 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches and additional branches (–6) aseptate, 7–15 × 3–5 μm each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 6–11 × 2–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (35–)36–40(–43) × (3−)3.5−4.5(−5) μm (av. 38 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies fast growing (60−85 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface cinnamon to brick with sparse, wooly, white aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse cinnamon to umber with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimen examined: New Zealand, Auckland, Auckland University Campus, from foliar lesion of Machaerina sinclairii, 27 Jan. 2008, C.F. Hill (holotype CBS-H22760, culture ex-type CBS 123183 = CPC 15378).

Notes: Calonectria machaerinae is a new species in the C. candelabrum complex. This species, along with C. brevistipitata, are the only two species to produce lateral stipe extensions in the C. candelabrum complex (Schoch et al., 1999, Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2015a). See note under C. brevistipitata for additional distinguishing characters.

Calonectria multilateralis L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818708. Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Calonectria multilateralis (ex-type CBS 110932). A–C. Macroconidiophores. D–E. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform to elongate reniform phialides. F. Conidiogenous apparatus with lateral stipe extension. G–J. Naviculate vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the multiple lateral stipe extensions on the macroconidiophores of this species.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicles; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 25–130 × 4–8 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 135–375 μm long, 5–6 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a naviculate vesicle, 6–11 μm diam; lateral stipe extensions (90° to main axis) numerous, 55–100 μm long, 3–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in naviculate vesicles, 4−8 μm. Conidiogenous apparatus 45–95 μm wide, and 30–70 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 10–25 × 3–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 6–20 × 3–5 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 7–15 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches and additional branches (–7) aseptate, 6–13 × 2–4 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform to elongate reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 6–12 × 2–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (27−)31–35(–38) × 3–4 μm (av. 33 × 3 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies fast growing (55−85 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface buff with abundant white, wooly aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on the colony surface; reverse buff to sienna, chlamydospores not observed.

Specimens examined: Mexico, Uxmal, from soil, Apr. 1994, P.W. Crous (holotype CBS-H22762, culture ex-type CBS 110932 = CPC 957); ibid., cultures CBS 110926 = CPC 947, CBS 110927 = CPC 948, CBS 110931 = CPC 956, CBS 115615 = CPC 915.

Notes: Calonectria multilateralis is a new species in the C. naviculata complex (Alfenas et al. 2015). The macroconidia of C. multilateralis [31–35(–38) × 3–4 μm (av. 33 × 3 μm)] are smaller than those of C. naviculata [(40−)42–50 × 3(–4) μm (av. 45 × 3 μm); Crous 2002] and C. multinaviculata [(40−)44–49(–52) × (2.5−)3.5(–4) μm (av. 46 × 3.5 μm); Alfenas et al. 2015].

Calonectria paracolhounii L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818709. Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Calonectria paracolhounii (ex-type CBS 114679). A–B. Macroconidiophores. C–D. Clavate vesicles. E–F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and elongate doliiform to doliiform to reniform phialides. G. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–B = 50 μm; C–G = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the fact that this species has an asexual morph that is very similar to that of C. colhounii.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 21–75 × 5–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 82–178 μm long, 3–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a narrowly clavate vesicle, 3–5 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 31–77 μm wide, and 25–54 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 11–23 × 3–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 7–13 × 3–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 7–12 × 2–4 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides elongate doliiform to doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 6–12 × 2–5 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (37–)39–43(–45) × 4−5 μm (av. 41 × 5 μm), 3-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (25−55 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface buff to sienna with abundant buff to white, felty to wooly aerial mycelium and moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse buff to sienna to umber with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimens examined: USA, substrate unknown, 1990s, A.Y. Rossman (holotype CBS-H22763 culture ex-type CBS 114679 = CPC 2445). Australia, fruit of Annona reticulata, 1988, D. Hutton, culture CBS 114705 = CPC 2423.

Notes: Calonectria paracolhounii is a new species in the C. colhounii complex (Lombard et al., 2010b, Chen et al., 2011). The macroconidia of C. paracolhounii [(37–)39–43(–45) × 4−5 μm (av. 41 × 5 μm)] are smaller than those of C. colhounii [(45–)60–70(–80) × (4−)5(−6) μm (av. 65 × 5 μm); Crous 2002], C. eucalypti [(66–)69–75(–80) × (5−)−6 μm (av. 72 × 6 μm); Lombard et al. 2010b], C. fujianensis [(48–)50–55(–60) × (2.5−)3.5−4.5(−5) μm (av. 52.5 × 4 μm); Chen et al. 2011], C. monticola 46–51(–56) × 4−5 μm (av. 49 × 5 μm); Crous et al. 2015b] and C. pseudocolhounii [(49–)55–65(–74) × (3.5−)4−5(−5.5) μm (av. 60 × 4.5 μm); Chen et al. 2011]. Hutton & Sanewski (1989) initially identified isolate CBS 114705 as C. colhounii, associated with leaf and fruit spots of custard apple (Annona reticulata). Their identification was based on morphological comparisons, as no DNA sequence data was available for the genus Calonectria at that time.

Calonectria parva L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818710. Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.

Calonectria parva (ex-type CBS 110798). A. Macroconidiophore. B–C. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and cylindrical to allantoid phialides. D–E. Narrowly clavate vesicles. F. Macroconidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the small macroconidiophores in this fungus.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and rarely a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 43–149 × 5–7 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 65–95 μm long, 2–4 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a narrowly clavate vesicle, 3–5 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 18–33 μm wide, and 24–43 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 11–21 × 3–5 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 11–15 × 3–4 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–4 phialides; phialides cylindrical to allantoid, hyaline, aseptate, 9–19 × 3–5 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (60–)66–78(–83) × 5−7 μm (av. 72 × 6 μm), (1−)3-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies fast growing (55−85 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface buff with abundant buff to white, felty aerial mycelium and sparse to moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse buff; chlamydospores not observed.

Specimen examined: South Africa, Mpumalanga, Sabie, D.R. de Wet nursery, from Eucalyptus grandis ramets (roots), 11 May 1990, P.W. Crous (holotype CBS-H22764, culture ex-type CBS 110798 = CPC 410 = PPRI 4001).

Note: Calonectria parva can be distinguished from other species in the genus by its relatively small macroconidiophores, which rarely bear a stipe extension.

Calonectria plurilateralis L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818711. Fig. 15.

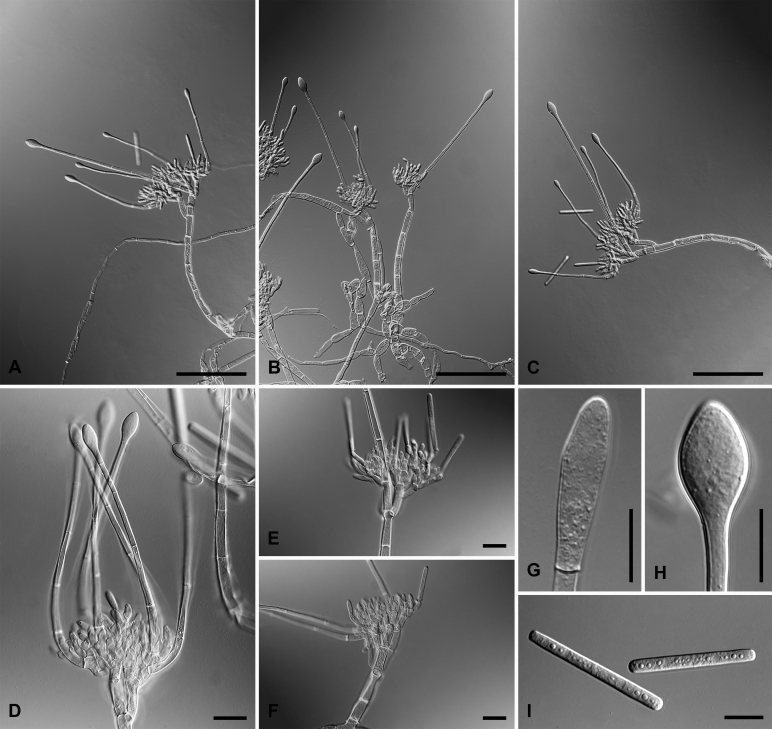

Fig. 15.

Calonectria plurilateralis (ex-type CBS 111401). A–C. Macroconidiophores with lateral stipe extensions. D. Conidiogenous apparatus with lateral stipe extensions. E–F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. G–H. Obpyriform to ellipsoidal vesicles. I. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A–C = 50 μm; D–K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the multiple lateral stipe extensions on the macroconidiophores of this fungus.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and numerous lateral stipe extensions terminating in vesicles, lacking a central stipe extension; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 50–130 × 4–7 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 110–180 μm long, 4–7 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in obpyriform to ellipsoid vesicles, 7–11 μm diam; lateral stipe extensions (90° to main axis) abundant, 75–105 μm long, 3–6 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in obpyriform to ellipsoid vesicles, 5−7 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 25–80 μm wide, and 25–85 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 11–39 × 2–9 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 7–17 × 3–5 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 6–12 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches aseptate, 8 × 4 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 4–11 × 3–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (27−)30–38(–41) × (3−)3.5−4.5(−5) μm (av. 34 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies fast growing (60−85 mm diam) on MEA after 7 d at room temperature; surface sienna to sepia with moderate white, wooly aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on the colony surface; reverse sienna to sepia, chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Specimen examined: Ecuador, from soil, 20 Jun. 1997, M.J. Wingfield (holotype CBS-H22766, culture ex-type CBS 111401 = CPC 1637).

Note: Calonectria plurilateralis can be distinguished from other members of the C. cylindrospora complex by its numerous lateral stipe extensions.

Calonectria pseudoecuadoriae L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818712. Fig. 16.

Fig. 16.